Key Points

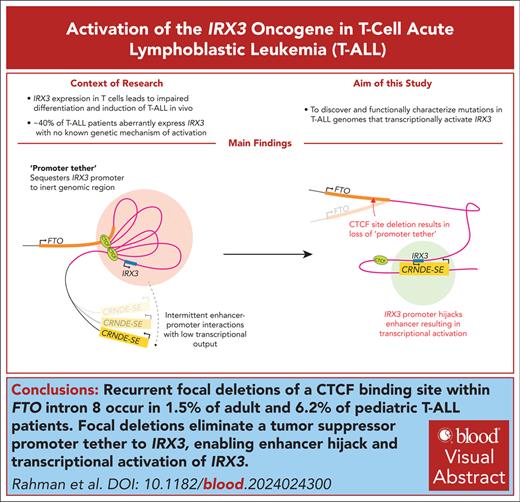

Recurrent focal deletions of a CTCF-binding site within FTO intron 8 occur in 1.5% of adult and 6.2% of pediatric patients with T-ALL.

Focal deletions eliminate a tumor suppressor promoter tether to IRX3 enabling enhancer hijack and transcriptional activation of IRX3.

Visual Abstract

Oncogenes can be activated in cis through multiple mechanisms including enhancer hijacking events and noncoding mutations that create enhancers or promoters de novo. These paradigms have helped parse somatic variation of noncoding cancer genomes, thereby providing a rationale to identify noncanonical mechanisms of gene activation. Here we describe a novel mechanism of oncogene activation whereby focal copy number loss of an intronic element within the FTO gene leads to aberrant expression of IRX3, an oncogene in T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (T-ALL). Loss of this CTCF-bound element downstream to IRX3 (+224 kb) leads to enhancer hijack of an upstream developmentally active super-enhancer of the CRNDE long noncoding RNA (−644 kb). Unexpectedly, the CRNDE super-enhancer interacts with the IRX3 promoter with no transcriptional output until it is untethered from the FTO intronic site. We propose that “promoter tethering” of oncogenes to inert regions of the genome is a previously unappreciated biological mechanism preventing tumorigenesis.

Introduction

The noncoding genome harbors differing classes of cis-regulatory elements including distal enhancers, poised promoters, and insulators that ensure precise control of gene expression across specialized tissues.1 In cancer, somatically acquired mutations of the noncoding genome can transcriptionally activate oncogenes through indels that generate de novo enhancers and promoters,2-9 by focal amplification of long-range enhancers,10,11 through deletion of boundary elements12-15 and structural rearrangements that lead to enhancer hijack.16-18

Previously, first-in-class mechanisms of oncogene activation after somatic mutation of the noncoding genome were discovered in T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (T-ALL), including cis-acting mutations that create neomorphic enhancers, and recurrent focal deletions that disrupt boundaries between insulated neighborhoods to activate TAL1 and LMO2 oncogenes, respectively.5,12 Although most T-ALL oncogenes TAL1, LMO2, TLX1, TLX3, NKX2-1, and MYB are ectopically expressed by well-characterized mechanisms, some have no known genetic lesion and thus provide an opportunity for the discovery of novel mechanisms of oncogene activation.19,20

In this study, we identify recurrent deletions of FTO intron 8 (FTOint8del) in a subgroup of patients with T-ALL. These patients exhibit aberrant expression of IRX3, a putative oncogene in T-ALL with no known genetic driver.21 Mechanistically, we show that IRX3 is normally tethered to a CTCF site within FTO intron 8, a transcriptionally inert region with minimal transcriptional output. Deletion of FTO intron 8 releases this “tether,” enabling IRX3 to be hijacked by a distal highly active developmental super-enhancer of CRNDE, resulting in IRX3 transcription. We posit that “promoter tethering” to inert regions of the genome is a previously unappreciated tumor suppressor mechanism, ensuring proto-oncogenes remain protected from activation by distal developmental super-enhancers.

Methods

Detailed methods are described in the supplemental Data (available on the Blood website). Recurrent FTO intron 8 deletions were discovered by analysis of St. Jude (Liu et al),20 UKALL2003, and ICGZ Poznan T-ALL primary patient cohorts. IRX3 expression data from available patient samples were determined by RNA sequencing (RNA-seq). Frequency of FTO intron 8 CTCF and MYB site deletions were identified by digital droplet polymerase chain reaction (PCR) on an unselected cohort of patient samples with T-ALL. CRISPR/Cas9 was used to make FTO intron 8 CTCF site and MYB site deletions in PF-382 cells. IRX3 expression was determined by quantitative PCR. CTCF knockdown was achieved by electroporation of small interfering RNA pools, and knockdown was validated by quantitative PCR. Looping interactions from FTO intron 8 CTCF site and IRX3 promoter were identified by chromosome conformation capture with unique molecular identifiers (UMI-4C). Enhancer-promoter (E-P) interactions in ALL-SIL cells were identified by chromatin immunoprecipitation for H3K27ac and high throughput chromosome conformation capture (HiChIP). ATAC-seq was used to characterize the CRNDE super-enhancer in FTO wild-type and FTO intron 8 CTCF site deleted cells. CRISPR/Cas9 was used to delete the CRNDE super-enhancer in ALL-SIL cells. All CRISPR/Cas9 edits were confirmed by flanking PCR. Public data sets used are described throughout the manuscript and referenced accordingly.

Ethical approval for UKALL2003 obtained from the Scottish Multi-Centre Research Ethics Committee on 25 February 2003 (ref: 02/10/952). Ethical approval for UKALL14 obtained from London-Fulham Research Ethics Committee (ref: 09/H0711/90). All samples were collected from patients with an informed consent according to the Declaration of Helsinki.

Results

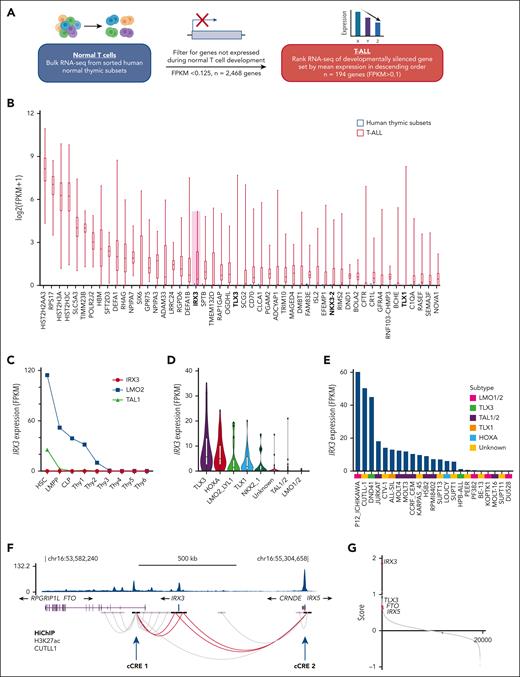

IRX3 is aberrantly expressed in T-ALL with E-P contacts to neighboring genes FTO, CRNDE, and IRX5

We hypothesized that genes aberrantly expressed in T-ALL compared with their developmentally matched normal cellular counterpart might uncover previously unrecognized oncogenes, enabling us to explore novel mechanisms of oncogene activation. Thus, we generated a list of genes that were not expressed in normal thymic subsets (fragments per kilobase of transcript per million mapped reads [FPKM] <0.125; n = 2468) and ranked their mean expression in 264 childhood cases of T-ALL (Figure 1A).20,22 Within the top 50 aberrantly expressed gene list were well-characterized T-ALL oncogenes such as TLX3, TLX1, and NKX3-2, validating this explorative approach (Figure 1B; supplemental Table 1). Our attention was drawn to IRX3 (rank 20), given recent reports licensing it as an oncogene through its ability to immortalize hematopoietic stem cells and induce T-lymphoid leukemias in vivo.21IRX3 encodes for an Iroquois-family homeobox transcription factor essential for limb bud pattern formation, nephron segmentation, and cardiac function, but with no known role in normal hematopoiesis.23-25

IRX3 is aberrantly expressed in T-ALL and resides in a shared topologically associated domain with E-P contacts to neighboring genes FTO, CRNDE, and IRX5. (A) Schematic outlining the comparative analysis conducted on bulk RNA-seq from developing T-cell subsets (National Center for Biotechnology Information Gene Expression Omnibus accession #GSE69239) and bulk RNA-seq from St. Jude’s pediatric T-ALL cohort (Liu et al, n = 264)20 to identify aberrantly expressed genes. (B) Box and whisker plot showing expression of top 50 genes aberrantly expressed in the St. Jude’s pediatric T-ALL cohort (n = 264) compared with normal hematopoietic progenitors (NCBI GEO accession #GSE69239); hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs), lymphoid primed multipotent progenitors (LMPPs), common lymphoid progenitors (CLPs), and T-cell subsets (Thy1-6). Expression values for T-cell subsets are from 2 replicates for each population and expression is FPKM averaged for each cell type. T-ALL cohort genes are ranked along the x-axis by mean expression. (C) Line graph tracking IRX3, LMO2, and TAL1 expression by RNA-seq across hematopoietic and thymic progenitors. RNA-seq from NCBI GEO accession #GSE69239, with the following immunophenotypic definitions: from bone marrow CD34+ cells, CD34+CD38–Lin− (HSCs), CD34+CD45RA+CD38+CD10−CD62LhiLin− (LMPPs), CD34+CD38+CD10+CD45RA+Lin− (CLPs); from thymic CD34+ cells, CD34+CD7−CD1a−CD4−CD8− (Thy1), CD34+CD7+CD1a−CD4−CD8− (Thy2), and CD34+CD7+CD1a+CD4−CD8− (Thy3); from thymic CD34− cells, CD4+CD8+ (Thy4), CD3+CD4+CD8− (Thy5), and CD3+CD4−CD8+ (Thy6). (D) Violin plot showing IRX3 expression (FPKM) by RNA-seq from the St. Jude primary T-ALL cohort separated by class-defining oncogenic subtypes (n = 264). (E) Bar chart showing IRX3 expression (FPKM) by RNA-seq from T-ALL cell lines (n = 24) and labeled by oncogenic subtype. (F) E-P interactions about the IRX3 locus mapped by HiChIP after pull-down for H3K27ac from the IRX3-positive CUTTL1 T-ALL cell line (NCBI GEO accession #GSE115896) and ChIP-seq for H3K27ac in CUTTL1 cells. Loops between IRX3 and cCREs for IRX3 are highlighted in red and indicated with arrows. (G) Ranked gene list by comparing IRX3-positive (top, n = 59) vs IRX3-negative (bottom, n = 59) T-ALL samples by RNA-seq from the St. Jude cohort. The y-axis ranking score metric for each gene was calculated by the GSEA “Signal2Noise” computational method for categorical phenotypes. Genes are listed along the x-axis in order of the ranked score. cCREs, candidate cis-regulatory elements.

IRX3 is aberrantly expressed in T-ALL and resides in a shared topologically associated domain with E-P contacts to neighboring genes FTO, CRNDE, and IRX5. (A) Schematic outlining the comparative analysis conducted on bulk RNA-seq from developing T-cell subsets (National Center for Biotechnology Information Gene Expression Omnibus accession #GSE69239) and bulk RNA-seq from St. Jude’s pediatric T-ALL cohort (Liu et al, n = 264)20 to identify aberrantly expressed genes. (B) Box and whisker plot showing expression of top 50 genes aberrantly expressed in the St. Jude’s pediatric T-ALL cohort (n = 264) compared with normal hematopoietic progenitors (NCBI GEO accession #GSE69239); hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs), lymphoid primed multipotent progenitors (LMPPs), common lymphoid progenitors (CLPs), and T-cell subsets (Thy1-6). Expression values for T-cell subsets are from 2 replicates for each population and expression is FPKM averaged for each cell type. T-ALL cohort genes are ranked along the x-axis by mean expression. (C) Line graph tracking IRX3, LMO2, and TAL1 expression by RNA-seq across hematopoietic and thymic progenitors. RNA-seq from NCBI GEO accession #GSE69239, with the following immunophenotypic definitions: from bone marrow CD34+ cells, CD34+CD38–Lin− (HSCs), CD34+CD45RA+CD38+CD10−CD62LhiLin− (LMPPs), CD34+CD38+CD10+CD45RA+Lin− (CLPs); from thymic CD34+ cells, CD34+CD7−CD1a−CD4−CD8− (Thy1), CD34+CD7+CD1a−CD4−CD8− (Thy2), and CD34+CD7+CD1a+CD4−CD8− (Thy3); from thymic CD34− cells, CD4+CD8+ (Thy4), CD3+CD4+CD8− (Thy5), and CD3+CD4−CD8+ (Thy6). (D) Violin plot showing IRX3 expression (FPKM) by RNA-seq from the St. Jude primary T-ALL cohort separated by class-defining oncogenic subtypes (n = 264). (E) Bar chart showing IRX3 expression (FPKM) by RNA-seq from T-ALL cell lines (n = 24) and labeled by oncogenic subtype. (F) E-P interactions about the IRX3 locus mapped by HiChIP after pull-down for H3K27ac from the IRX3-positive CUTTL1 T-ALL cell line (NCBI GEO accession #GSE115896) and ChIP-seq for H3K27ac in CUTTL1 cells. Loops between IRX3 and cCREs for IRX3 are highlighted in red and indicated with arrows. (G) Ranked gene list by comparing IRX3-positive (top, n = 59) vs IRX3-negative (bottom, n = 59) T-ALL samples by RNA-seq from the St. Jude cohort. The y-axis ranking score metric for each gene was calculated by the GSEA “Signal2Noise” computational method for categorical phenotypes. Genes are listed along the x-axis in order of the ranked score. cCREs, candidate cis-regulatory elements.

In contrast to the developmental oncogenes TAL1 and LMO2, IRX3 is not expressed in any normal T-cell precursor (Figure 1C). Further analysis of the pediatric T-ALL cohort separated according to their class-defining oncogenic subtypes showed that a greater proportion of the patients in the TLX3 and HOXA subgroups had aberrant IRX3 expression (defined as FPKM >1) compared with the other subgroups (86% vs 23%; Fisher exact test statistic <0.00001) (Figure 1D).20 Overall, aberrant IRX3 expression is observed in 49% of adults (22 of 45) and 42% of pediatric patients with T-ALL (111 of 264) (supplemental Figure 1B). IRX3-positive patients had a higher incidence of NOTCH1 mutations (88% vs 65%; P < .0001), CTCF mutations (12% vs 2%; P < .001), PHF6 mutations (38% vs 14%; P < .0001), JAK-STAT pathway mutations (37% vs 16%; P < .0001), and NOTCH-MYC enhancer amplification (21% vs 5%; P < .0001), but a lower incidence of PI3K pathway mutations (15% vs 39%; P < .0001; supplemental Figure 2; supplemental Table 2). Furthermore, 74% of T-ALL cell lines (17 of 23) exhibited aberrant IRX3 expression (Figure 1E; supplemental Figure 1B).

Analysis of published high throughput chromosome conformation capture (Hi-C) data from normal human thymic tissue identified IRX3 within a single topologically associated domain (TAD) shared with FTO, IRX5, and CRNDE encompassing ∼1.3 Mb (supplemental Figures 3 and 4). To identify E-P loops from IRX3, we next examined HiChIP data from the IRX3-positive CUTLL1 T-ALL cell line and identified 2 candidate intra-TAD cis-regulatory elements, which we named cCRE_1 (within FTO) and cCRE_2 (at CRNDE/IRX5) (Figure 1F). In addition, generation of a rank-ordered gene list by comparing IRX3-negative and IRX3-positive primary T-ALL samples (n = 118) by RNA-seq identified the expression of multiple genes positively correlated with IRX3 messenger RNA (mRNA) levels including FTO at rank 64 and IRX5 at rank 109 of 19 464 total genes (Figure 1G), suggesting coordinated long-range intra-TAD interactions.

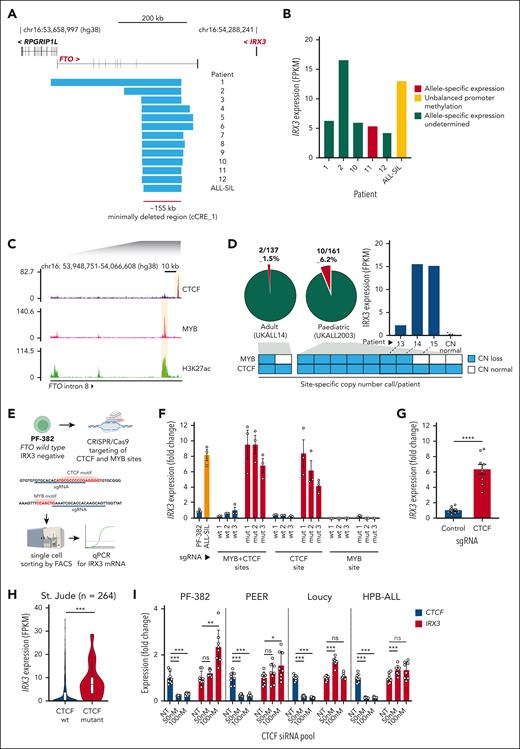

FTO intron 8 is recurrently deleted in patients with T-ALL

We next explored whether copy number aberrations (CNAs) affected the IRX3 candidate cis-regulatory elements by examining copy number calls from published data sets of primary T-ALL patient samples and T-ALL cell lines. This analysis revealed 13 T-ALL genomes (12 of patient origin and 1 cell line, ALL-SIL) with heterozygous copy number losses impinging on the FTO gene, and notably all intersected with cCRE_1 (Figure 2A; supplemental Table 3). Expression data were available for 6 of 13 T-ALL samples and all exhibited aberrant expression of IRX3 mRNA (Figure 2B). Owing to the relatively small size of IRX3 coding sequences (∼2.6 kb), the gene often lacks informative heterozygous single nucleotide polymorphisms to make consistent allele-specific expression (ASE) calls. However, we were able to confirm ASE in one patient sample, and ALL-SIL had evidence of promoter methylation allelic imbalance, a proxy for ASE (supplemental Figure 5). Both these findings were indicative of a heterozygous cis-acting genetic lesion (Figure 2B).

Recurrent deletions of FTO intron 8 in patients with T-ALL impinge on a CTCF-binding site. (A) Focal heterozygous deletions identified in T-ALL genomes at FTO; 12 originate from primary patient samples and 1 from the ALL-SIL T-ALL cell line. Deletions identified in patient samples are from multiple cohorts including St. Jude (n = 264), UKALL2003 (n = 148), and ICGZ Poznan (n = 63). (B) IRX3 expression (FPKM) by RNA-seq from matched primary patient samples and the ALL-SIL T-ALL cell line harboring FTO intron 8 deletions. Allele-specific expression identified in patient 11 was determined by St. Jude’s previous analyses, and unbalanced promoter methylation for the ALL-SIL cell line was ascertained by analysis of the Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia Promoter Methylation data set. (C) ChIP-seq for CTCF (NCBI GEO accession #GSE68976), MYB, and H3K27ac (NCBI GEO accession #GSE76783) in the Jurkat T-ALL cell line centered on the minimally deleted region within FTO intron 8. (D) Pie charts showing the frequency of FTO intron 8 deletions determined by digital droplet PCR in adult (n = 137) and pediatric T-ALL cohorts (n = 161). Stacked boxes summarize CTCF or MYB site-specific copy number calls for each patient identified with FTO intron 8 deletions and a bar chart showing IRX3 expression (FPKM) is shown for patient samples where matched RNA was available for sequencing. Matched IRX3 expression by RNA-seq for samples that exhibited normal copy number (n = 9, UKALL14 cohort) are also plotted. (E) Experimental outline for CRISPR/Cas9-mediated disruption of FTO intron 8 CTCF and MYB sites in the PF-382- (FTOwt) and IRX3-negative (FPKM <1) T-ALL cell line. (F) Bar chart showing IRX3 expression determined by quantitative PCR (qPCR) for PF-382 (FTOwt) and ALL-SIL (FTOint8del) T-ALL cell lines and unedited (wt) and edited (mut) clones. Data presented are 3 technical replicates ± standard deviation for each biological sample. (G) Bar chart showing IRX3 expression determined by qPCR for PF-382 polyclonal edited cells after CRISPR/Cas9-mediated disruption of the FTO intron 8 CTCF site. Technical replicates from 3 independent experiments are shown. P < .0001 from a 2-tailed t test. (H) Violin plot showing IRX3 expression (FPKM) of primary T-ALL samples with (n = 16) and without (n = 248) CTCF mutations from the St. Jude T-ALL cohort. P = .0007 from 2-tailed t test. (I) Bar chart showing CTCF and IRX3 expression by qPCR after CTCF knockdown in PF-382, PEER, Loucy, and HPB-ALL T-ALL cell lines. Final CTCF small interfering RNA (siRNA) pool concentrations used are shown on the x-axis, where NT is a negative control nontargeting siRNA pool. Technical replicates from 2 independent experiments are shown. Statistical comparisons were made to NT groups by a 2-tailed t test where ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001; and ns, not significant. mut, mutant; sgRNA, single guide RNA; wt, wild-type.

Recurrent deletions of FTO intron 8 in patients with T-ALL impinge on a CTCF-binding site. (A) Focal heterozygous deletions identified in T-ALL genomes at FTO; 12 originate from primary patient samples and 1 from the ALL-SIL T-ALL cell line. Deletions identified in patient samples are from multiple cohorts including St. Jude (n = 264), UKALL2003 (n = 148), and ICGZ Poznan (n = 63). (B) IRX3 expression (FPKM) by RNA-seq from matched primary patient samples and the ALL-SIL T-ALL cell line harboring FTO intron 8 deletions. Allele-specific expression identified in patient 11 was determined by St. Jude’s previous analyses, and unbalanced promoter methylation for the ALL-SIL cell line was ascertained by analysis of the Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia Promoter Methylation data set. (C) ChIP-seq for CTCF (NCBI GEO accession #GSE68976), MYB, and H3K27ac (NCBI GEO accession #GSE76783) in the Jurkat T-ALL cell line centered on the minimally deleted region within FTO intron 8. (D) Pie charts showing the frequency of FTO intron 8 deletions determined by digital droplet PCR in adult (n = 137) and pediatric T-ALL cohorts (n = 161). Stacked boxes summarize CTCF or MYB site-specific copy number calls for each patient identified with FTO intron 8 deletions and a bar chart showing IRX3 expression (FPKM) is shown for patient samples where matched RNA was available for sequencing. Matched IRX3 expression by RNA-seq for samples that exhibited normal copy number (n = 9, UKALL14 cohort) are also plotted. (E) Experimental outline for CRISPR/Cas9-mediated disruption of FTO intron 8 CTCF and MYB sites in the PF-382- (FTOwt) and IRX3-negative (FPKM <1) T-ALL cell line. (F) Bar chart showing IRX3 expression determined by quantitative PCR (qPCR) for PF-382 (FTOwt) and ALL-SIL (FTOint8del) T-ALL cell lines and unedited (wt) and edited (mut) clones. Data presented are 3 technical replicates ± standard deviation for each biological sample. (G) Bar chart showing IRX3 expression determined by qPCR for PF-382 polyclonal edited cells after CRISPR/Cas9-mediated disruption of the FTO intron 8 CTCF site. Technical replicates from 3 independent experiments are shown. P < .0001 from a 2-tailed t test. (H) Violin plot showing IRX3 expression (FPKM) of primary T-ALL samples with (n = 16) and without (n = 248) CTCF mutations from the St. Jude T-ALL cohort. P = .0007 from 2-tailed t test. (I) Bar chart showing CTCF and IRX3 expression by qPCR after CTCF knockdown in PF-382, PEER, Loucy, and HPB-ALL T-ALL cell lines. Final CTCF small interfering RNA (siRNA) pool concentrations used are shown on the x-axis, where NT is a negative control nontargeting siRNA pool. Technical replicates from 2 independent experiments are shown. Statistical comparisons were made to NT groups by a 2-tailed t test where ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001; and ns, not significant. mut, mutant; sgRNA, single guide RNA; wt, wild-type.

We next analyzed potential regulatory elements within the minimally deleted region (∼155 kb) of FTO intron 8 by examining chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing (ChIP-seq) data sets from the FTO wild-type Jurkat T-ALL cell line (Figure 2C). This region was largely devoid of high-amplitude ChIP-seq peaks, except for a single CTCF-binding peak and a single MYB peak enriched with H3K27ac. From this we hypothesized that loss of CTCF and/or MYB binding within FTO intron 8 may be involved in dysregulated IRX3 expression (Figure 2C). To explore this hypothesis further, we developed a digital droplet PCR assay capable of distinguishing CNA at the CTCF- and MYB-binding sites (supplemental Figure 6). This had 2 aims, first to ascertain the frequency of FTO intron 8 CNAs in a larger cohort of primary T-ALL samples and second to allow for independent copy number calls at both loci where differences between the calls may provide mechanistic insight. Among 298 unselected primary T-ALL samples collected at diagnosis, CNAs within FTO intron 8 were more common in pediatric than adult T-ALL (10 of 161 [6.2%] vs 2 of 137 [1.4%], respectively; P = .04 by χ2 test; Figure 2D). Although 8 of 12 had copy number loss at both the CTCF and MYB sites, notably 4 of 12 had heterozygous copy number loss of the CTCF site alone, suggesting that loss of this CTCF site is most likely to be functionally relevant. Furthemore, we identified aberrant IRX3 expression in 3 patients with these lesions by analysis of patient matched RNA-seq (Figure 2D). The average fractional abundance of these heterozygous mutations was 35% across the 12 patient samples, suggesting these mutations are clonal and present in >70% T-ALL blasts (supplemental Figure 7).

CRISPR/Cas9-mediated disruption of FTO intron 8 CTCF site transcriptionally activates IRX3

To functionally validate whether loss of the CTCF and/or MYB site was capable of upregulating IRX3 expression, we used CRISPR/Cas9 editing in the FTO wild-type, IRX3-negative PF-382 T-ALL cell line (Figure 2E; supplemental Figure 8; supplemental Table 4). Single cell clones with deletions of ∼12 kb, impinging on both CTCF- and MYB-binding sites, thus mimicking the copy number losses observed in the primary patient samples, led to significant upregulation of IRX3 to levels comparable with FTOint8del ALL-SIL cells (Figure 2F; supplemental Figure 9). Crucially, similar upregulation was observed in clones with sole disruptive indels of the CTCF-binding site, but not those affecting the MYB site alone. Furthermore, deletion of the CTCF-binding site in a polyclonal population led to a significant increase of IRX3 mRNA relative to unedited controls (Figure 2G). These data strongly implicate loss of the CTCF site as the key driver of aberrant IRX3 expression in patients with FTOint8del.

Given that many IRX3-positive T-ALL samples do not harbor FTOint8del (106 of 109 with FPKM >1, St. Jude cohort), we postulated that mutations of CTCF itself, which are recurrent in T-ALL genomes, may create the same phenotype. To explore this, we compared RNA-seq data from CTCF wild-type and CTCF mutant T-ALL samples and found significantly higher IRX3 expression in the CTCF mutant group (Figure 2H; supplemental Table 5). To address this functionally, we knocked down CTCF with small interfering RNAs in a panel of T-ALL cell lines and observed significant IRX3 upregulation in PF-382, PEER, Loucy, and HPB-ALL cells but not in other cell lines (Figure 2I; supplemental Figure 10), suggesting the CTCF-IRX3 axis is influenced by variations in the genomic context.

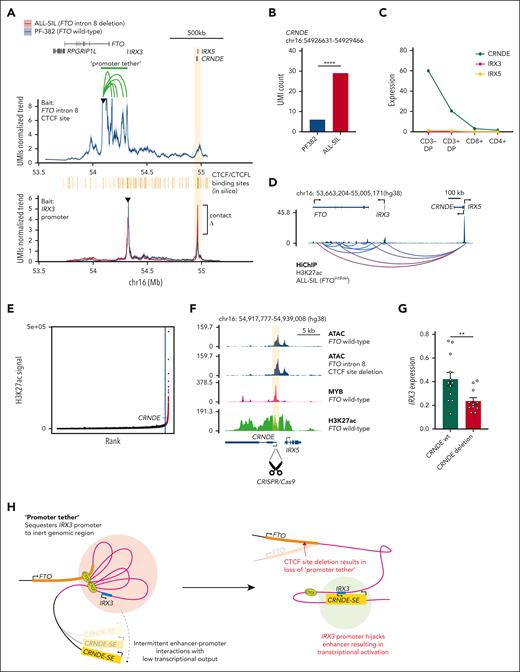

Focal deletion of the IRX3 “promoter tether” within FTO intron 8 enables enhancer hijack by the CRNDE developmental super-enhancer

Given the importance of CTCF as an architectural protein, we quantified interactions from the FTO intron 8 CTCF site and IRX3 promoter by UMI-4C. Baiting the FTO intron 8 CTCF site in PF-382 cells (IRX3 negative) revealed a dense cluster of looping interactions between the CTCF site and IRX3, suggesting that the proximal promoter of IRX3 is tethered to the FTO intron 8 in the wild-type setting (Figure 3A; supplemental Figure 11). By comparing ALL-SIL cells (IRX3 positive, FTOint8del) and PF-382 cells (IRX3 negative, FTOwt), we observed a marked increase in the number of interactions between the IRX3 promoter bait and the CRNDE locus in ALL-SIL cells, previously identified as cCRE_2 (Figure 3A-B). The same was observed in PF-382 clones with CRISPR/Cas9-induced disruption of the CTCF-binding site in FTO intron 8, providing strong evidence for causality (supplemental Figure 12). Interestingly, CRNDE is expressed at high levels (FPKM >20) in developing CD3 double-positive thymocytes and downregulated through normal T-cell differentiation (Figure 3C). HiChIP for H3K27ac in ALL-SIL (FTOint8del) also showed enhancer loops originating from the CRNDE/IRX5 locus to IRX3 (Figure 3D). Further examination of the CRNDE locus by H3K27ac ChIP-seq in PF-382 cells classified this locus as a super-enhancer (113th of 23 737 total enhancers by ROSE), with broad H3K27ac marks covering the IRX5 and CRNDE promoters and gene bodies (Figure 3E-F). The CRNDE super-enhancer does not seem to be regulated by the FTO intron 8 locus, given that PF-382 cells harboring CTCF-binding site deletions did not alter the ATAC-seq signal intensity (Figure 3F). In contrast, disruption of the CRNDE super-enhancer in ALL-SIL (FTOint8del) cells using CRISPR/Cas9 resulted in significant downregulation of IRX3 expression (P value = .01; Figure 3G; supplemental Figure 13), consistent with the hypothesis that aberrant expression of IRX3 is driven by increased interaction with the CRNDE super-enhancer.

Transcriptional activation of IRX3 in T-ALL by loss of a promoter tether and enhancer hijack from the CRNDE locus. (A, top panel) UMI-4C contact profile generated by baiting the FTO intron 8 CTCF site in PF-382 (FTOwt) cells. A green bar highlights the contacts that form a promoter tether between IRX3 and FTO intron 8. (A, bottom panel) UMI-4C contact profile generated by baiting the IRX3 proximal promoter in the PF-382 (FTOwt) and ALL-SIL (FTOint8del) T-ALL cell line. CTCF/CTCFL-binding sites across the FTO, IRX3, and CRNDE/IRX5 locus were in silico predicted by HOCOMOCO v11. (B) UMI count of interactions between the IRX3 proximal promoter and the CRNDE locus (P = .0005; Fisher exact test; UMI4Cats analysis package). (C) Expression (FPKM) of CRNDE, IRX5, and IRX3 across T-cell subsets by RNA-seq from the Blueprint Epigenome Project, sample TH91. (D) ChIP-seq for H3K27 acetylation (NCBI GEO accession #GSM1816978) and E-P loops generated by HiChIP for H3K27 acetylation in the ALL-SIL (FTOint8del) T-ALL cell line about the FTO, IRX3, and CRNDE/IRX5 locus. Loops shown passed a q-value threshold of 0.01 at a bin size of 40 kb and were called by FitHiChIP. (E) Rank ordering of super-enhancers in the PF-382 (FTOwt) T-ALL cell line by using H3K27ac ChIP-seq (NCBI GEO accession #GSE76783). Red points indicate genomic regions classed as super-enhancers which includes the CRNDE locus. (F) ATAC-seq at the CRNDE/IRX5 locus in PF-382 (FTOwt) and PF-382 (FTO intron 8 CTCF site deleted) T-ALL cell lines, in addition to ChIP-seq for MYB (NCBI GEO accession #GSM2466687) and H3K27ac (NCBI GEO accession #GSM2037796) in PF-382 (FTOwt) T-ALL cells. Shaded box represents peak region targeted to disrupt the CRNDE super-enhancer by CRISPR/Cas9 excision. (G) Expression level of IRX3 mRNA as determined by qPCR from ALL-SIL (FTOint8del) T-ALL cell line after CRISPR/Cas9-mediated deletion of the CRNDE super-enhancer locus. (H) Proposed mechanism of action whereby promoter tethering of IRX3 to the relatively inert FTO intron 8 locus by CTCF binding allows infrequent E-P interactions and low transcriptional output. Subsequent focal deletion of this intronic CTCF site leads to loss of the promoter tether and enhancer hijack of the CRNDE super-enhancer. mRNA, messenger RNA.

Transcriptional activation of IRX3 in T-ALL by loss of a promoter tether and enhancer hijack from the CRNDE locus. (A, top panel) UMI-4C contact profile generated by baiting the FTO intron 8 CTCF site in PF-382 (FTOwt) cells. A green bar highlights the contacts that form a promoter tether between IRX3 and FTO intron 8. (A, bottom panel) UMI-4C contact profile generated by baiting the IRX3 proximal promoter in the PF-382 (FTOwt) and ALL-SIL (FTOint8del) T-ALL cell line. CTCF/CTCFL-binding sites across the FTO, IRX3, and CRNDE/IRX5 locus were in silico predicted by HOCOMOCO v11. (B) UMI count of interactions between the IRX3 proximal promoter and the CRNDE locus (P = .0005; Fisher exact test; UMI4Cats analysis package). (C) Expression (FPKM) of CRNDE, IRX5, and IRX3 across T-cell subsets by RNA-seq from the Blueprint Epigenome Project, sample TH91. (D) ChIP-seq for H3K27 acetylation (NCBI GEO accession #GSM1816978) and E-P loops generated by HiChIP for H3K27 acetylation in the ALL-SIL (FTOint8del) T-ALL cell line about the FTO, IRX3, and CRNDE/IRX5 locus. Loops shown passed a q-value threshold of 0.01 at a bin size of 40 kb and were called by FitHiChIP. (E) Rank ordering of super-enhancers in the PF-382 (FTOwt) T-ALL cell line by using H3K27ac ChIP-seq (NCBI GEO accession #GSE76783). Red points indicate genomic regions classed as super-enhancers which includes the CRNDE locus. (F) ATAC-seq at the CRNDE/IRX5 locus in PF-382 (FTOwt) and PF-382 (FTO intron 8 CTCF site deleted) T-ALL cell lines, in addition to ChIP-seq for MYB (NCBI GEO accession #GSM2466687) and H3K27ac (NCBI GEO accession #GSM2037796) in PF-382 (FTOwt) T-ALL cells. Shaded box represents peak region targeted to disrupt the CRNDE super-enhancer by CRISPR/Cas9 excision. (G) Expression level of IRX3 mRNA as determined by qPCR from ALL-SIL (FTOint8del) T-ALL cell line after CRISPR/Cas9-mediated deletion of the CRNDE super-enhancer locus. (H) Proposed mechanism of action whereby promoter tethering of IRX3 to the relatively inert FTO intron 8 locus by CTCF binding allows infrequent E-P interactions and low transcriptional output. Subsequent focal deletion of this intronic CTCF site leads to loss of the promoter tether and enhancer hijack of the CRNDE super-enhancer. mRNA, messenger RNA.

Discussion

In this study, we discovered recurrent focal deletions of FTO which explains aberrant IRX3 expression in a subgroup of patients with T-ALL. Although CTCF mutations may have the same consequence, the mechanism for aberrant IRX3 expression in other patients with T-ALL currently remains unclear. From a clinical perspective, it is also uncertain whether targeting IRX3, or its pathway, offers a feasible therapeutic approach or whether the FTO deletions can be used to track minimal residual disease. Although situated downstream to IRX3, deletion of this long-range insulator counterintuitively permits enhancer hijack of an upstream super-enhancer. This is distinct from canonical TAD fusion events in cancer whereby focal deletions or methylation disrupts boundary elements positioned between the oncogene and cis-regulatory effector.12,13,15,26 In contrast to previously discovered enhancer hijack events, where the E-P interaction remains naïve until the structural rearrangement occurs, we reveal interactions between the IRX3 promoter and CRNDE super-enhancer in IRX3-negative cells.16-18 We posit that the IRX3 promoter is sequestered to a relatively inert region of FTO intron 8, yielding minimal transcriptional output, despite residual interactions with the CRNDE super-enhancer (Figure 3H). This sequestration is facilitated by CTCF binding at the FTO intron leading to the formation of a “promoter tether.” Therefore, loss of this CTCF site by focal deletion untethers the IRX3 promoter, providing an example of E-P competition occurring within the same TAD (Figure 3H). This differs from recent findings in acute myeloid leukemia describing an intronic long noncoding RNA in FTO that regulates IRX3 expression.27 Together, these findings add to the complex regulatory relationship between the FTO and IRX3 genes first identified through the discovery of obesity-associated germ line variants.28,29 We further speculate that promoter tethering to inert regions of the genome is a previously unappreciated tumor suppressor mechanism through which potent oncogenes are protected from activation by nearby developmental super-enhancers. Integrating 3-dimensional promoter interactions with copy number data may highlight further examples of this phenomenon, potentially explaining the functional consequence of recurrent focal deletions in noncoding genomes of cancers that as yet remain unexplained.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the patients, families, and clinical teams who have been involved in all trials. Samples were acquired with support from laboratory teams in the Bristol Genetics Laboratory, Southmead Hospital, Bristol, United Kingdom; Molecular Biology Laboratory, Royal Hospital for Sick Children, Glasgow, United Kingdom; Molecular Haematology Laboratory, Royal London Hospital, London, United Kingdom; and Molecular Genetics Service and Sheffield Children’s Hospital, Sheffield, United Kingdom. S.R. thanks A. Motazedian, A. Das, E. Wainwright, D. Vassiliadis, and J. Balic for academic discussions pertaining to this study and Lorna Neal for invaluable nonacademic discussions.

This work was supported in part by Cancer Research UK CRUK/A13920 to A.K.F. for UKALL14 trial and CRUK/A21019 to A.K.F. for UKALL14 Biobank. M.R.M. is supported through a Great Ormond Street Hospital (GOSH) Children’s Charity Professorship. This work was also supported by the Francis Crick Institute, which receives its core funding from Cancer Research UK (CC2008), the UK Medical Research Council (CC2008), and the Wellcome Trust (CC2008). P.V.L. is a Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas (CPRIT) Scholar in Cancer Research and acknowledges CPRIT grant support (RR210006). M.D. and P.V.V. were supported by the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under grant agreement no. 952304. S.R. was supported by a John Goldman Fellowship from Leukaemia UK. This project was supported by funding from the National Center for Research and Development (304586/304586/5/NCBR/2017). Primary childhood leukemia samples used in this study were provided by VIVO Biobank, supported by Cancer Research UK and Blood Cancer UK (grant CRCPSC-Dec21∖100003).

Authorship

Contribution: S.R. and M.R.M. designed the study and wrote the manuscript; S.R., G.B., N.F., J.R.C., D.O., R.P., T.R.-D., and A.T. conducted wet-lab experiments; J.D., L.W., R.J., and P.V.L. performed bioinformatic analysis; S.L. and A.K.F. were responsible for sample collection, processing, and storage of UKALL2003 and UKALL14 samples; J.R., P.V.V., M.D., J.R.H., J.O.J.D., A.G., M.A.K., and M.A.D. were involved in data interpretation and provided additional samples and resources to complete this study; S.H. provided training for the UMI-4C technique used in this study; and all authors revised and agreed to the final version of the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: J.D. and J.R.H. are cofounders and shareholders of Nucleome Therapeutics and provide consultancy to the company. J.D. has intellectual property licensed to Beam Therapeutics, receives revenue from this license, and holds personal shares. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Marc R. Mansour, Department of Haematology, University College London, London WC1E 6BT, United Kingdom; email: m.mansour@ucl.ac.uk; and Sunniyat Rahman, Department of Haematology, University College London, London WC1E 6BT, United Kingdom; email: sunniyat.rahman@ucl.ac.uk.

References

Author notes

Public deposits of FASTQ files where this has not been done previously can be found at NCBI GEO with accession numbers GSE279517, GSE279520, and GSE279521. Copy number analyses of cancer cell lines are available at https://sites.broadinstitute.org/ccle/datasets.

Data are available on request from the corresponding authors, Marc R. Mansour (m.mansour@ucl.ac.uk) and Sunniyat Rahman (sunniyat.rahman@ucl.ac.uk).

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

There is a Blood Commentary on this article in this issue.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.