Key Points

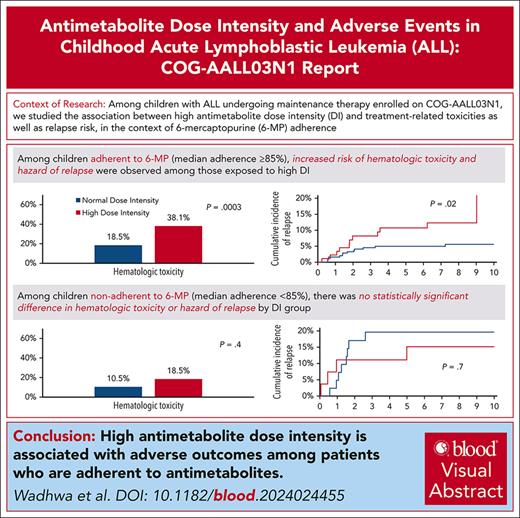

High antimetabolite dose intensity during maintenance therapy for childhood ALL is associated with elevated odds of hematologic toxicities.

Among those who adhere to 6-mercaptopurine, high antimetabolite dose intensity is associated with significantly elevated hazard of relapse.

Visual Abstract

The association between antimetabolite dose intensity (DI) and adverse events among children receiving maintenance therapy for acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) remains unclear, especially in the context of antimetabolite adherence. Using Children’s Oncology Group AALL03N1 data, we examined the association between high DI during the first 4 study months and (i) treatment-related toxicities during the subsequent 2 study months; and (ii) relapse risk. Patients were classified into a high DI phenotype (either 6-mercaptopurine [6-MP] or methotrexate [MTX] DI ≥110% during the first 4 study months, or 6-MPDI or MTXDI 100%-110% at study enrollment and ≥25% increase over the 4 study months) and normal DI phenotype (all others). Only patients with wild-type TPMT and NUDT15 were included. 6-MP adherence data were available for 63.7% of study participants and used to stratify as adherent (median adherence ≥85%) and nonadherent (median adherence <85%) participants. Multivariable analyses were adjusted for sociodemographic and clinical prognosticators. Of the 644 patients, 29.3% were exposed to high DI. High DI was associated with a 2.1-fold greater odds of hematologic toxicity (95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.4-3.1; reference: normal DI) in the entire cohort and 2.9-fold higher among adherers (95% CI = 1.6-5.1); odds were comparable among nonadherers (2.1-fold; 95% CI = 0.4-10.1). Although high DI was not associated with relapse in the entire cohort (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR] = 1.4; 95% CI = 0.8-2.4), it was associated with a greater hazard of relapse among adherent participants (aHR = 2.4; 95% CI = 1.0-5.5) but not among nonadherent participants (aHR = 0.9; 95% CI = 0.2-3.8). Dose escalation above protocol doses during maintenance therapy for ALL should be done cautiously after assessing adherence to prescribed therapy.

Introduction

Children diagnosed with acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) have excellent outcomes.1 Successful treatment of childhood ALL consists of risk-based induction, response-adapted postinduction therapy, and a maintenance phase consisting of oral self-administration or parental administration of mercaptopurine (6-MP) daily and methotrexate (MTX) weekly.2,3 Previous studies have demonstrated the need for adequate antimetabolite systemic exposure to ensure durable remissions.4 In addition to pharmacogenetics, adequate systemic exposure is dependent on prescribed dose intensity (DI; ratio of prescribed dose/planned protocol dose),5 and adherence to the prescribed dose.5-7 The conventional practice of titrating DI to ensure myelosuppression is based on prior reports describing an association between inadequate myelosuppression and increased relapse risk.8,9 However, attempts to determine an association between antimetabolite DI and relapse risk have produced conflicting results, likely as previous studies did not take antimetabolite adherence into consideration.10-12 The Children’s Oncology Group Study AALL03N1 showed that 6-MP nonadherence was associated with a greater hazard of relapse5-7; however, among adherent patients, treatment interruptions resulted in high intraindividual variability in 6-MPDI and in thioguanine nucleotide (TGN) levels, increasing the risk of relapse.5

Current guidelines recommend antimetabolite dose titration to achieve adequate myelosuppression (assessed using monthly absolute neutrophil counts [ANCs] and platelet counts), regardless of the antimetabolite adherence status. Thus, it is possible that antimetabolite dose titration strategies, especially among adherent patients, may result in unintended treatment-related toxicities, which may promote treatment interruptions and relapse risk. Whether antimetabolite DI affects relapse risk in the context of adherence to antimetabolites remains unclear. In this secondary analysis of AALL03N1, we investigated whether high antimetabolite (6-MP and MTX) DI during maintenance is associated with treatment-related toxicities and relapse, in the context of adherence to therapy.

Materials and methods

AALL03N1 enrolled patients diagnosed with ALL at age ≤21 years who had completed at least 6 months of maintenance therapy and were in first remission. Additional details and primary findings of AALL03N1 have been previously published.5-7,13,14 The study schema is provided in supplemental Figure 1 (available on the Blood website). All participating sites had approval from local institutional review boards. Patients and/or parents/legal guardians provided written informed consent before study enrollment. The current analysis excluded patients with heterozygous or homozygous TPMT deficiency or mutant NUDT15 genotype (performed in a research setting in patients enrolled on AALL03N1; n = 50, 6.7%) to allow for assessment of antimetabolite DI across a homogeneous population. Patients with missing antimetabolite DI information were excluded (n = 48, 6.5%).

Patients (≥18 years at enrollment) or parents provided details on sociodemographics (annual household income, parental education, and race/ethnicity) at study entry. Participating sites provided details on clinical characteristics of study participants (age at ALL diagnosis, sex, age at enrollment, National Cancer Institute [NCI] risk grouping [standard risk: age ≤9.99 years and white blood cell count <50 000 cells/μL at ALL diagnosis; high risk if otherwise], ALL subtype [B-cell ALL or T-cell ALL], leukemic blast cytogenetics [favorable: t(12;21), hyperdiploidy, trisomy 4 and 10, or trisomy 4, 10, and 17; unfavorable: t(9;22), t(4;11), hypodiploidy, or extreme hypodiploidy; neutral: neither favorable nor unfavorable]). Intrachromosomal amplification of chromosome 21 was not considered a high-risk cytogenetic lesion at the time AALL03N1 opened for enrollment and hence was not collected. Data regarding minimal residual disease were also not collected. Participating sites completed case report forms every month for a total of 6 months, reporting the prescribed 6-MP and MTX doses on each day of the prior month. Sites also reported laboratory values from the monthly clinic visits, which included ANC (cells/μL), platelet count (cells/mm3), alanine aminotransferase (IU/L), aspartate aminotransferase (IU/L), and direct bilirubin (mg/dL). Additionally, sites reported whether 6-MP or MTX was held by the provider during the prior month (along with dates chemotherapy was held), and the reasons for the hold (low ANC or platelets, elevated liver enzymes and/or bilirubin, infection/illness, or other reasons). Erythrocyte TGN levels were measured from monthly blood samples submitted by sites. Periodic updates (every 6 months for the first 5 years; annually for the next 5 years) on clinical outcomes (vital status, relapse, or subsequent neoplasm) were collected from participating sites. A subgroup of patients enrolled on the parent trial ALL03N1 (n = 470/742, 63%) used the electronic medication monitoring device (TrackCap Medication Events Monitoring System [MEMS]; MWV Switzerland Ltd) for measuring 6-MP adherence for 6 months6; this group is identified as the MEMS subcohort in the current report.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using SAS software version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc) and 2-sided tests with P < .05 were considered statistically significant. Correction for multiple testing was not performed. 6-MPDI and MTXDI over the first 4 study months were calculated by dividing daily prescribed doses by planned protocol doses (6-MP: 75 mg/m2 per day; MTX: 20 mg/m2 per week) and were expressed as a percentage. Exposure (DI) was calculated over the first 4 study months to create high DI and normal DI phenotypes. Treatment-related toxicity was measured over the study months 5 and 6. Patients were classified as either having the high DI phenotype (either 6-MPDI or MTXDI ≥110% at any time during the first 4 study months, or 6-MPDI or MTXDI 100% to 110% at study enrollment accompanied by a ≥25% increase over the first 4 study months) or the normal DI phenotype (all others).

DI and treatment-related toxicity

Hematologic toxicity was defined as ANC <500 cells/μL, platelet count <50 000 cells/mm3, or treatment interruption in the previous month due to “low” ANC or “low” platelet count. Nonhematologic toxicity was defined as aspartate aminotransferase or alanine aminotransferase >20-fold above the upper limit of normal, direct bilirubin >2.0 mg/dL, or hold due to “elevation of liver enzymes and/or bilirubin” or “infection/illness” in the past month. We examined the association between high DI and treatment-related toxicity using logistic regression, adjusting for age at study enrollment, sex, and race/ethnicity; the model restricted to the MEMS subcohort included 6-MP adherence rates, in addition to the above variables. In the MEMS subcohort, we also conducted analyses stratified by median adherence rates ≥85% (adherent) and <85% (nonadherent); a previous report from AALL03N1 identified significant hazard of relapse at 85% adherence level6 and allows for adequate patient size in both groups to allow comparison.

DI and relapse risk

We examined the hazard of relapse (from end of study month 4) associated with the high DI phenotype using proportional subdistribution hazard regression models treating death as competing risk and adjusting for age at study enrollment, sex, race/ethnicity, NCI risk group, blast cytogenetics, treatment interruptions, and time from start of maintenance therapy to study enrollment. Given the collinearity between treatment-related toxicity and treatment interruptions, the former was not included in the model. For patients in the MEMS subcohort, models for relapse risk included 6-MP adherence in addition to the above variables. Stratified analyses were conducted in the MEMS subcohort, for those with adherence rates of ≥85% and <85%.

Results

Of the 742 patients enrolled on AALL03N1, 50 (6.7%) were excluded due to TPMT or NUDT15 polymorphisms and 48 (6.5%) due to missing DI data, resulting in 644 (86.8%) patients retained in this secondary analysis (supplemental Figure 2). supplemental Table 1 compares patients included in the analysis vs those excluded. Patients retained in the analysis were younger at diagnosis (median, 5 vs 5.5 years; P < .001) and at study enrollment (6 vs 7 years; P < .001), had longer follow-up since enrollment (7.9 vs 5.3 years; P = .008), and were more likely to have NCI standard risk ALL (59.0% vs 46.4%; P = .02).

As shown in Table 1, the median age at ALL diagnosis was 5 years (range, 1-18 years) and at study enrollment was 6 years (range, 2-19 years). The cohort was followed up for a median of 7.9 years (range, 0.2-13.0 years) from enrollment. A total of 444 patients were male (68.9%); 17.9% were African-American or Black, 15.2% were Asian, 33.4% were Hispanic, and 33.5% were non-Hispanic White. Most patients had B-cell ALL (89.2%), NCI standard risk disease (59.0%) with neutral blast cytogenetics (50.7%). Of the 644 participants retained in this secondary analysis, 410 (63.7%) had provided adherence data and are referred to as the MEMS subcohort (supplemental Table 2). Median adherence in the MEMS subcohort was 96.4% (range, 15.1%-100%); 82.9% of patients had median adherence ≥85%.

The high DI group (n = 189; 29.3%) did not differ from the normal DI group (Table 1). In the MEMS subcohort (supplemental Table 2), patients with high DI had lower median adherence compared with those with the normal DI phenotype (94.6% [range, 17.2%-100%] vs 97.0% [range, 15.1%-100%]; P = .02). Along similar lines, the proportion of patients with median adherence ≥85% was significantly lower in the high DI group (76.1% vs 85.7%; P = .02). supplemental Table 3 compares median DI between patients in the normal and high DI group during months 1 to 4; median DI was expectedly significantly higher in the high DI group compared with normal DI. supplemental Table 4 compares ANC between normal and high DI groups during months 1 to 4; median ANC also was expectedly significantly higher among patients in the high DI group. Erythrocyte TGN levels were compared between patients in normal vs high DI groups, and no significant differences were noted (supplemental Table 5).

DI and treatment-related toxicities

Among patients with evaluable toxicity data during study months 5 and 6, 22.1% (133 of 601) experienced hematologic toxicity and 20.2% (71 of 351) experienced nonhematologic toxicity. Comparison of patients with and without treatment-related toxicities is presented in supplemental Table 6 (hematologic toxicity) and supplemental Table 7 (nonhematologic toxicity).

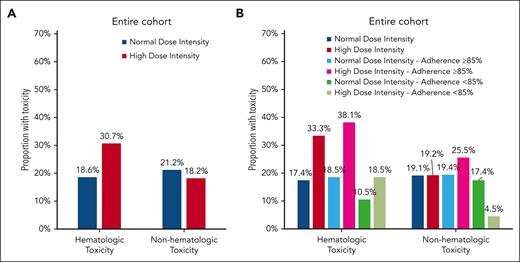

As shown in Figure 1A, a greater proportion of the high DI group experienced hematologic toxicity (30.7% vs 18.6%; P = .001). The proportion of patients with nonhematologic toxicity was comparable among those in the high vs normal DI group (18.2% vs 21.2%; P = .5). Adjusting for age at study enrollment, sex, and race/ethnicity, the high DI group was at a 2.1-fold (95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.4-3.1; P < .001) greater odds of experiencing hematologic toxicity (Table 2). In contrast, the odds of nonhematologic toxicity were comparable in the high DI group (odds ratio [OR] = 0.9; 95% CI = 0.5-1.6; P = .7).

Proportion of patients with toxicities by antimetabolite DI in the entire cohort (A) and MEMS subcohort (B).

Proportion of patients with toxicities by antimetabolite DI in the entire cohort (A) and MEMS subcohort (B).

In the MEMS subcohort (Figure 1B), the high DI group was more likely to experience hematologic toxicity (33.3% vs 17.4%; P < .001), but had comparable rates of nonhematologic toxicity (19.2% vs 19.1%; P = .9). After adjusting for age at study enrollment, sex, race/ethnicity, and 6-MP adherence, the high DI group was at a 2.8-fold (95% CI = 1.7-4.8; P < .001) greater odds of experiencing hematologic toxicity compared with the normal DI group. Odds of nonhematologic toxicity were comparable between the 2 groups (OR = 1.1; 95% CI = 0.5-2.4; P = .7; Table 2).

Among adherent patients, the high DI group was significantly more likely to experience hematologic toxicity (38.1% vs 18.5%; P < .001, Figure 1B; OR = 2.9, 95% CI = 1.6-5.1, P < .001, Table 2) compared with the normal DI group. In contrast, among nonadherent patients, the proportion of patients with high DI who experienced hematologic toxicity (18.5%) was not statistically different from those with normal DI (10.5%; P = .4; Figure 1B); this was also reflected in the multivariable analysis (OR = 2.1; 95% CI = 0.4-10.1; P = .4; Table 2). The proportion of patients with nonhematologic toxicity did not show a statistically significant difference by DI phenotype among the adherent patients (normal vs high DI: 19.4% vs 25.5%; P = .4) or nonadherent patients (normal vs high DI = 17.4% vs 4.5%; P = .2) (Figure 1B).

supplemental Tables 8 and 9 highlight the prevalence and risk of hepatotoxicity and infectious toxicity separately; no significant differences in hepatotoxicity and infectious toxicity were observed between normal and high DI groups.

DI and relapse risk

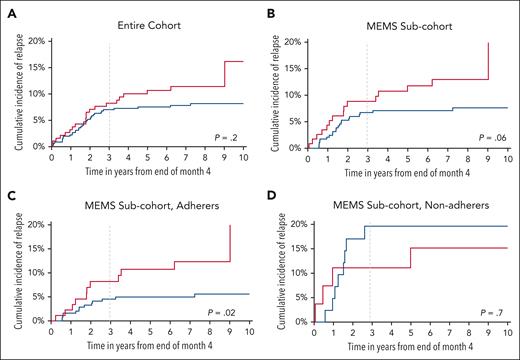

After a median follow-up of 7.9 years (range, 0.2-13.0 years), 57 patients experienced relapse of their primary disease. The 3-year cumulative incidence of relapse from end of study period was 8.3% (±2.1%) among the high DI group vs 7.0% (±1.2%) among the normal DI group (P = .2) (Figure 2A). In a multivariable model (supplemental Table 10) adjusting for age at study enrollment, sex, race/ethnicity, NCI risk group, blast cytogenetics, treatment interruptions, and time from start of maintenance, patients in the high DI group had a comparable hazard of relapse (hazard ratio [HR] = 1.4; 95% CI = 0.8-2.4; P = .2).

Cumulative incidence of relapse (CIR) among eligible participants. (A) Entire cohort; (B) MEMS sub-cohort; (C) adherers in MEMS sub-cohort; (D) nonadherers in MEMS sub-cohort.

Cumulative incidence of relapse (CIR) among eligible participants. (A) Entire cohort; (B) MEMS sub-cohort; (C) adherers in MEMS sub-cohort; (D) nonadherers in MEMS sub-cohort.

In the MEMS subcohort, 37 patients relapsed, yielding a 3-year cumulative incidence of 8.8% (±2.7%) in the high DI group vs 6.7% (±1.5%) in the normal DI group (P = .06) (Figure 2B). As shown in supplemental Table 10, patients in the MEMS subcohort with high DI had a comparable hazard of relapse (HR = 1.5; 95% CI = 0.8-3.1; P = .2).

Among adherent patients, the cumulative incidence of relapse at 3 years from end of study period was significantly higher among patients in high DI group compared with those with normal DI (8.2% [±3.0%] vs 4.5% [±1.3%]; P = .02) (Figure 2C). In the multivariable model, the high DI group had a 2.4-fold greater hazard of relapse (95% CI = 1.0-5.5; P = .04; reference: normal DI) (Table 3). In contrast, the cumulative incidence of relapse at 3 years from end of study period among nonadherent patients was comparable between high DI and normal DI groups (11.1% [±6.2%] vs 19.6% [±6.3%]; P = .7) (Figure 2D). Additionally, there was no association between the DI phenotype and hazard of relapse among the nonadherent patients (HR = 0.9; 95% CI = 0.2-3.8; P = .9; Table 3).

Discussion

Current recommendations call for antimetabolite dose titration to maintain the white blood cell and/ or absolute neutrophil count within a narrow range, with the overarching goal of ensuring adequate systemic exposure to antimetabolites and minimizing relapse risk. This practice often results in an increase in antimetabolite DI. However, the benefits and harms of this approach remain largely unknown. In this secondary analysis of AALL03N1, we find that exposure to high DI is associated with significantly elevated odds of subsequent hematologic toxicity. Additionally, we find that exposure to high DI is not associated with reduction in risk of relapse compared with patients exposed to normal DI. On the contrary, we find that a subset of patients who are adherent to oral 6-MP and are exposed to high antimetabolite DI have a significantly elevated hazard of relapse compared with those not exposed to high DI.

6-MP and MTX are the backbone of maintenance therapy for childhood ALL.2,15,16 Barring host pharmacogenomics (such as TPMT polymorphisms or NUDT15 mutations), most treatment protocols recommend standard doses of 6-MP (50-75 mg/m2 per day) and MTX (20 mg/m2 per week), with further dose titration based on myelosuppression and/or hepatotoxicity. This practice assumes that the effect of antimetabolites on white blood cells or neutrophils correlates with its effect on leukemic blasts, although studies examining this association have produced conflicting results.8,17-19 ANC is inversely correlated with adherence to oral 6-MP, and nonadherence is directly associated with relapse.5 Hence, lack of myelosuppression could simply reflect lack of adherence to prescribed treatment. Nonetheless, protocols typically call for dose escalation when there is lack of myelosuppression during maintenance. Although the design of this study precludes ascribing causality, lower adherence among patients with high DI likely reflects suboptimal consumption of antimetabolites, thus prompting treating physicians to increase DI. Children’s Oncology Group ALL treatment protocols recommend increasing 6-MP and/or MTX dose by 25% over protocol doses among patients with inadequate myelosuppression beyond the first cycle of maintenance. Our findings indicate that this practice could lead to subsequent dose-limiting hematologic toxicity in up to 40% of patients who are adherent to their treatment. These high-grade toxicities would warrant treatment interruptions that could increase intraindividual variation in TGN levels, thus placing the adherent patients at a higher risk of relapse.5 Additionally, high 6-MP exposure has been linked to greater risk of developing second malignant neoplasms in children with ALL.20,21 Escalation of antimetabolite DI should take into consideration whether the patient is adhering to prescribed therapy, and among adherent patients, should take into consideration the short-term toxicities as well as late effects.

The association between antimetabolite DI and relapse risk has yielded conflicting results over time, likely due to a variety of reasons.5,10,11 First, the studies were limited by lack of information on adherence to antimetabolites, given that nonadherent patients have higher ANC and are thus more likely to be prescribed higher doses.5,10,11 Second, studies demonstrating a protective effect of higher antimetabolite DI were conducted several decades ago,11 before intensification of upfront treatment and use of response-adapted therapy. AALL03N1 found no association between 6-MPDI and relapse risk, when using the median 6-MPDI values for creating a binary variable.5 The current study used a new definition of DI that included both 6-MPDI and MTXDI, and did not find an association between relapse risk and DI, even after adjusting for adherence. However, 6-MP adherent patients exposed to high DI were at a 2.4-fold greater hazard of relapse when compared with those exposed to normal DI. On the other hand, relapse risk remained high among nonadherers, independent of DI. The reasons for this observation are unclear. Adherent patients likely represent a group of children who did not demonstrate myelosuppression and thus received higher doses of antimetabolites to induce myelosuppression. We speculate that potential pharmacokinetic or pharmacogenomic differences may influence drug metabolism, thus leading to inadequate myelosuppression. Another hypothesis could involve arrest of leukemic blasts in certain phases of cell cycle on exposure to high DI, rendering them dormant and allowing for development of resistance to antimetabolites over time.22

Taken together, these findings highlight potential harm of dose escalation beyond protocol doses during maintenance treatment for childhood ALL among patients who adhere to prescribed treatment. A combination of lack of myelosuppression and 6-MP metabolite levels could help identify patients who are nonadherent to 6-MP. Additionally, adherence calculators that incorporate characteristics such as patient age, race/ethnicity, 6-MPDI and ingestion patterns, ANC, and household structure, perform well (area under curve: 0.74-0.79) at identifying patients nonadherent to 6-MP.23 In adherent patients where dose escalation is being considered due to inadequate myelosuppression, patients/families should be educated on high risk of subsequent hematologic toxicity, and the patients should be monitored closely.

This study has several limitations that should be considered when interpreting the findings. AALL03N1 enrolled patients after at least 6 months of maintenance therapy to allow for a stable dose of antimetabolite therapy. Although this allowed for a more accurate representation of the patients’ tolerance to chemotherapy, AALL03N1 did not capture toxicity that might have occurred before enrollment and could potentially influence antimetabolite DI during maintenance. We hypothesize that unmeasured nonhematologic toxicities (such as hepatic) from other drugs used during upfront treatment (asparaginase, vincristine, anthracyclines, and thioguanine) may cause clinicians to be cautious with dose escalation with antimetabolites to prevent reoccurrence, which may be why AALL03N1 observed a lower incidence of hepatic toxicity compared with hematologic toxicities. Additionally, AALL03N1 measured 6-MP adherence, 6MPDI and MTXDI, and toxicities for 6 months during maintenance therapy, and the current report makes the assumption that the dosing practices and the resultant toxicities during this period reflect the entire maintenance. Minimal residual disease was not routinely obtained during the time AALL03N1 was open for enrollment,24,25 and neither were recently recognized high-risk cytogenetics (such as intrachromosomal amplification of chromosome 2126 or Philadelphia-like ALL27). Despite these limitations, this is the first large, multicenter study to examine the association between high DI, treatment-related toxicities, and relapse risk in the context of adherence.

In conclusion, we find that antimetabolite dose escalation beyond protocol doses during maintenance therapy for childhood ALL is associated with greater hematologic toxicity and with no reduction in relapse risk. Among patients who adhere to prescribed therapy, high antimetabolite DI is associated with increased risk of relapse. ALL treatment protocols should emphasize assessment of adherence before considering dose escalation of antimetabolite chemotherapy.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge support from National Clinical Trials Network (NCTN) Operations Center grant (U10CA180886), NCTN Statistics & Data Center grant (U10CA180899), St. Baldrick's Foundation, and NCI Community Oncology Research Program grant (UG1CA189955) to the Children’s Oncology Group, as well as a National Cancer Institute grant (R01 CA096670) to S.B.

Authorship

Contribution: S.B. and W.L. designed AALL03N1, performed research, and collected, analyzed, and interpreted data; A.W. and S.B. designed this secondary analysis; A.W., Y.C., and S.B. performed statistical analysis; A.W. and S.B. wrote the initial draft of the manuscript; and L.H., A.A., D.S.D., J.P.N., Y.R., A.T., and F.L.W. performed research, interpreted data, reviewed the initial draft of the manuscript, and provided critical feedback. All authors have reviewed and agree on this final version of the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: A.A. is a medical director at Servier Pharmaceuticals. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Correspondence: Smita Bhatia, Institute for Cancer Outcomes and Survivorship, 1600 7th Ave S, Lowder 500, Birmingham, AL 35226; email: smitabhatia@uabmc.edu.

References

Author notes

Presented in part at the 65th annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology, San Diego, CA, 10 December 2023.

Requests for AALL03N1 deidentified data set should be directed to the corresponding author, Smita Bhatia (smitabhatia@uabmc.edu).

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.