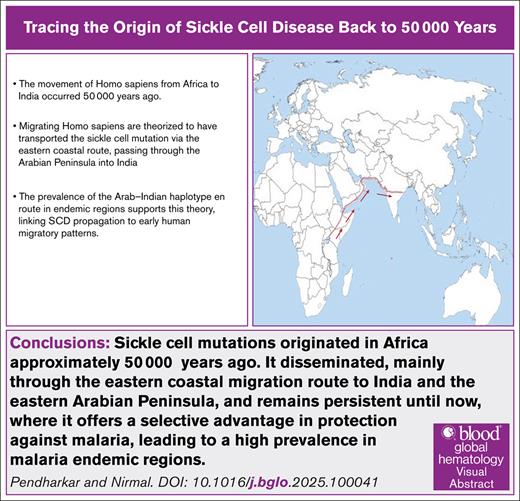

Visual Abstract

Sickle cell disease (SCD) is a genetic disorder resulting from a mutation in the hemoglobin β-globin gene and is predominantly found in malaria-endemic regions of sub-Saharan Africa and India. This review explores the origin and dissemination of SCD, hypothesizing its emergence in Africa 50 000 years ago under selective pressure from malaria. The movement of Homo sapiens to India occurred 50 000 years ago. Migrating H sapiens are theorized to have transported the mutation via the eastern coastal route, passing through the Arabian Peninsula into India. The prevalence of the Arab-Indian haplotype en route in endemic regions supports this theory, linking SCD propagation to early human migratory patterns. Genetic evidence reveals that tribal populations in central India, who practice endogamy, harbor the Arab-Indian haplotype with a high prevalence of SCD. This overlap of haplotype distributions between Africa, the Arabian Peninsula, and India underscores the evolutionary advantage of SCD in malaria-endemic zones. This well-documented evidence strengthens our proposed hypothesis that the origin of SCD occurred 50 000 years ago in Africa and spread to India via the Arabian Peninsula, providing protection from malaria to date.

Introduction

Sickle cell disease (SCD) is a genetic disorder that affects millions of people worldwide, with the highest prevalence recorded in sub-Saharan Africa, followed by the Asian subcontinent, especially India.1-3 It is caused by a mutation in the hemoglobin β (HBB) gene, resulting in the production of hemoglobin S. This mutation causes red blood cells to adopt a sickle-like shape, leading to complications, including vaso-occlusion, hemolysis, and end-organ damage.

The literature suggests that SCD originated several thousand years ago in certain regions of Africa.4 Presently, in the endemic regions of sub-Saharan Africa, it is estimated that each year, over 200 000 infants are born with this disorder.4 The sickle cell trait is present in up to 30% of the total African population, making it one of the most common genetic disorders on the continent. In India, the inhabitant population of endemic regions is termed “tribal.” To date, tribal lifestyles and practices resemble those of hunter-gatherers. Tribal customs include endogamy, which is practiced even today. The disease is most prevalent in these tribal populations, and the incidence of sickle cell traits among this population is as high as 40%.5 SCD has a significant effect on the health and well-being of affected populations in Africa, India, and around the globe.6

In Africa, the high prevalence of the sickle cell trait is attributed to the evolutionary advantage it provides against the deadly malaria parasite, which is endemic in many parts of the African continent. Similarly, the Indian territories associated with the high prevalence of the disease/trait are also known to be endemic for malaria.7

The examination of the origins and spread of SCD is crucial for developing effective prevention and treatment strategies, as well as for improving our overall understanding of human genetics and the evolution and migration of Homo sapiens. Despite exhaustive research on SCD thus far, little is known about its origin and spread, particularly in the context of global populations. Questions that remain unanswered include the factors that contributed to the emergence and dissemination of SCD in Africa and the spread of the disease to other parts of the world.

This review aims to fill this gap in knowledge by postulating the emergence and spread of SCD from Africa to India and other parts of the world and connecting it with present-day knowledge of the peopling of India.

We hypothesize that under the selective pressure of a high prevalence of malaria, sickle cell mutations originated in Africa ∼50 000 years ago. It disseminated, mainly through the eastern coastal migration route to India and the eastern Arabian Peninsula, and remains persistent until now, where it offers a selective advantage in protection against malaria, leading to a high prevalence in malaria-endemic regions.

Material and methods

Data sources

We searched biomedical literature databases of PubMed, Scopus, and the Cochrane Library for various studies published during the last 20 years (between January 2004 and October 2014), using the keywords, namely, sickle cell anemia, SCD, origin, evolution, Africa, and India in different combinations.

Data extraction

The abstracts of all the selected studies, identified through web search, were reviewed independently by 2 authors (D.P. and G.N.). While extracting the data, relevant parameters such as author’s name, journal name, year of publication, study design, objectives, methodology, results and outcomes, and other factors that can affect outcomes were carefully noted in an Excel sheet.

Origin of SCD

SCD is caused by a mutation in the gene that encodes hemoglobin, resulting in the production of abnormal red blood cells that can cause a range of health problems. The most common variant follows homozygosity of the sickle cell gene variant (HBB; c20T>A, p.Glu.6Val; OMIM: 141900 [HBBβs]) or the coinheritance of HBBβs and β0-thalassemia.8 This disease is most prevalent in the endemic zones of malaria, strengthening the hypothesis that the mutation provides a selective advantage by providing protection against malaria. Changes in hemoglobin offer protection from the severe forms of Plasmodium falciparum malaria.9-11 This may have led to a selective genomic population worldwide. The geographical distribution was strongest in the malaria-infested regions. Moreover, evidence suggests that the emergence of P falciparum from gorillas 40 000 to 60 000 years ago in West Africa around Cameroon.12

The equatorial regions of Africa that stretch from western Ghana through western Central Africa and down to the north of the Zambezi river basin probably harbor mutations longer than elsewhere.13,14 There is a low prevalence of the HBBβS gene in some parts of Africa that are not endemic to malaria.

There are 5 classical HBB haplotypes, namely, Senegal, Benin, Cameroon, Bantu (Central African Republic), and the Arab-Indian, based on their geographical location of detection (not origin).15-17

There are 2 main theories regarding the origin of SCD: unicentric and multicentric.15,18-21 The multicentric origin model suggested that the mutation occurred in multiple geographical regions and each haplotype represents an independent occurrence of the same exact mutation and posits 5 independent occurrences of the same mutation within the last few thousand years. Many researchers focus on the unicentric theory, which describes the emergence of sickle mutations at 1 place because recurrent mutations are less likely and the rate of mutation in hemoglobin genes is extremely slow to account for multiple independent events of the HBBβS variant.9,22,23HBBβs mutations coincide with population movement.

In the Shriner and Rotimi study, 2932 whole genomes from the 1000 Genomes Project, the African Genome Variation Project, and sequencing efforts in Qatar were analyzed. Of these, 156 genomes had a copy of the sickle cell mutation. They defined new haplotypes using phased sequence data, as opposed to using restriction sites, through which the 5 classical haplotypes were identified. Using mutation and recombination rates, they also hypothesized that the original sickle cell mutation arose 259 generations or ∼7300 years ago (Holocene), supporting the unicentric theory of origin. However, it is still uncertain whether the patterns observed by the scientists exist across a larger number of carriers and individuals with sickle cell anemia beyond the 156 involved in the published study.

Gene transfer was described as being among the rainforest hunter-gatherers. Gene flow could also have occurred between 10 000 and 20 000 years ago.24 Cameroon haplotypes appear to be the most common among all 5 haplotypes, suggesting that they may be the primary site of mutation.25

A 2019 study by Laval et al investigating the sickle cell mutation used genetic data analysis of human β-globin genes from 479 individuals across African populations. The researchers applied approximate Bayesian computation, a statistical method to estimate the age and origin of the sickle cell allele that accounts for factors such as population subdivision, past demography, and balancing selection. As analyzed in detail by Laval et al, the mean estimates confirm that βs occurred first in agriculturists at ∼22 000 years (late Pleistocene) and were later introduced into rainforest hunter-gatherers 6000 years ago.14

Peopling of the world and India

Most of these theories have proposed the origin of H sapiens in Africa.27 An appropriate model of recent human evolution is important for understanding our own history. One of the most accepted analyses on this topic, the Bayesian analysis model, points to an origin of our species ∼141 000 years ago, leading to dissemination out of Africa ∼51 000 years ago.28 Furthermore, it is postulated that there are 2 main routes of migration from Africa: land via northward and water via the southern coastal route. The southern coastal route model predicts that the early stages of dispersal occurred when people crossed the Red Sea to southern Arabia, but genetic evidence has hitherto been tenuous. Further analyses of mitochondrial DNA and the Y chromosome suggested that the first successful movement of modern humans out of Africa occurred ∼ 50 000 to 60 000 years ago.29-31 This pattern suggests that Arabia was the first stop in the journey of modern humans around the world.29

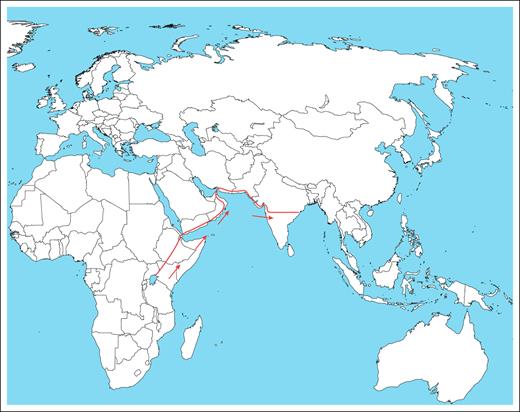

The hunter-gatherers moved from forests in Africa for various reasons. This migration may have been swift and possibly coastal along the Arabian Sea/Indian Ocean.32 Therefore, there is genomic evidence of admixture with ancient Iranian farmers, later Eurasian Steppe pastoralists and indigenous South Asians.32 The route is estimated to have followed the eastern Arabian coast (entry point to present-day eastern Saudi Arabia), passing through the Arabian Peninsula into India.

Most genetic variations in the Indian genome may have originated from a single major migration. A whole genome sequence study analyzing 2762 participants from 18 different states across India inferred the minimal coalescence time between Indians and sub-Saharan Africans was 53 932 (95% percentile range, 53 190-54 644) years ago.32 The literature indicates that most of the ancestry of present-day Indians is derived from a single migration event from Africa that occurred 50 000 years ago.32

If the theory of the coastal route were to be understood, people would have inhabited coordinate zones between 22° and 20° latitude on Earth. The corresponding tropical area in India has a large delta basin of 2 rivers, namely, Narmada and Tapi, which are encapsulated with thick forests. Notably, the sea level at the time of migration would have been 100 meters lower than it is today.32 One molecular dating study suggested that the origin of SCD was ∼7300 years ago (Holocene),25 whereas another study reported that the HBBβs mutation originated ∼22 000 years ago.14

Status of SCD

India ranks second worldwide in terms of the incidence of SCD.3 The prevalence of the sickle trait varies from 2% to 40% geographically, and the prevalence of the disease ranges from 0.5% to 3%. Most of the districts affected by the SCD are in central Indian states between 22° and 20° latitude coordinates. Among the states, Chhattisgarh, Madhya Pradesh, and Odisha had a prevalence of 28.23% (95 % confidence interval [CI], 4.3-52.15), 23.23% (95% CI, 0.48-34), and 12.34% (95% CI, 7.7-16.98), respectively, and are considered to have a high burden of sickle cell trait in India. Various genomic studies from India have confirmed that the haplotype is Arabic-Indian.5 According to Labie et al, “the HBS βS gene isolated from the tribal populations of India is associated with 1 predominant typical haplotype Arab-Indian, suggesting a unicentric origin of the mutation in India. Moreover, this finding substantiates the possible unicentric origin of the Indian tribal populations themselves. The gene must have arisen and spread before tribal dispersion.”18 (p479)

The countries comprising the migration route for H sapiens are estimated to have been Yemen, Oman, and Saudi Arabia.32 Yemen and Oman both reported a high prevalence of sickle cell trait and disease, and the predominant haplotype was identified to be Arab-Indian. In Oman, the percentages of sickle cell trait and disease occurrence are 4.8% to 6% and 0.2%, respectively.33 However, in Saudi Arabia, the distribution of the SCD trait is nonuniform, with the highest prevalence in Eastern Province, followed by southwestern. In addition, the reported prevalence rates of sickle cell trait and disease range from 2% to 27% and 2.6%, respectively.34

Discussion

It is well documented that Africa is the origin of H sapiens, and their movement out of Africa occurred ∼50 000 years ago.32 SCD originated under environmental and genetic selection pressures in geographical locations that are documented to be endemic to malaria in Africa.3 The H3Africa project reported that single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in the BCL11A loci and HBS1L-MYB (myeloblastosis) region (HMIP) and the coinheritance of α-thalassemia have an impact on fetal hemoglobin (HbF) level and clinical severity.

The migration of H sapiens from Africa to the South Asian subcontinent has been documented to have occurred via the coastal route and occurred ∼50 000 years ago.32 The coastal route involves crossing through the Arabian Peninsula, which corresponds to present-day Yemen, Oman and adjoining eastern Saudi Arabia, and entering India at ∼22° and 20° latitude (Figure 1). High-resolution haplotype network (SNP-based, phased), sharing statistics (eg, f-statistics/D-stats), and demographic modeling (eg, qpGraph/fastsimcoal2/ approximate Bayesian computation) could add to the additional information. Presently, the geological coordinates for the entry point for the haplotype are in the central part of India, spanning from the Gulf of Khambhat (Arabian Sea-Indian Ocean) in the west to the Bay of Bengal in the east. This region corresponds to an extremely thick forest with a high malaria incidence, such as the African Zambezi basin. The evidence suggests that the incidence of SCD is high in the Indian population in all these areas and that the predominant haplotype in the affected regions is Arab-Indian. Interestingly, the same Arab-Indian SCD phenotype is common to the population of Saudi Arabia, encompassing the migration route.

A map showing the possible migration route of people with SCD from Africa to India.

A map showing the possible migration route of people with SCD from Africa to India.

Currently, the inhabitant population of this area is tribal, and their traditional practices resemble those of hunter-gatherers. The high incidence of SCD in these tribal-inhabited areas corroborates the hypothesis of a “very old” persistence of the disease. Moreover, an endogamous society ensures the preservation of SCD in the local population. This high prevalence of SCD in the isolated region of India highlights the multiplicity of survival of the gene, suggesting a strong possibility of “very old” roots of the origin of the SCD gene.

The dispersion and circulation of HBS genes in the modern world provide valuable clues for the regional expression of SCD and, more importantly, for piecing together human migration. This may be the missing piece of the puzzle linking and interpreting out-of-Africa migration theories, thereby aiding our understanding of HBS gene evolution and dissemination from Africa.

The origin and spread of SCD to India and the exact geographical location with the highest prevalence suggest a common route and time of dispersal from Africa. In addition, it could be theorized that upon entry, H sapiens moved into the forests and settled there, ensuring minimal propagation of the HBS-harboring gene population, thereby isolating SCD from the malaria-endemic region. Furthermore, it can also be deduced that the current Indian tribals may be descendants of the selective population that migrated to India and the South Asian subcontinent as early as 50 000 years ago and are still inhabiting the “secluded zone.”

Conclusion

H sapiens originated in Africa. According to the theory of migration, modern man originated in Africa and then dispersed to the rest of the Earth, including India. Migration into the South Asian subcontinent (including India) occurred 50 000 years ago via the eastern coastal route from Africa by crossing the Arabian Peninsula, including Yemen, Oman, and eastern Saudi Arabia. SCD is most prevalent in Africa, followed by India; however, the origin and spread of the disease remain contentious. The Indian inhabitants corresponding to the entry-point latitudinal coordinates are tribals who live in thick forests and practice endogamy. Their practices resemble those of hunter-gatherers. In addition, as found in Africa, the tribal inhabited, SCD-prevalent region in India remains the endemic zone for malaria, providing protection from the disease.

The overlap of the commonest haplotype, the Arab-Indian, between Yemen, Oman, Saudi Arabia, and India also indicates the eastern coastal migration route from Africa. The tribal population harboring the haplotype in India remains isolated in endogamous societies, making the propagation of SCD minimal and thereby conserving the genetics of the disease. This evidence strengthens our proposed hypothesis that the origin of SCD occurred 50 000 years ago in Africa and spread to India via the Arabian Peninsula, providing protection from malaria to date.

Authorship

Contribution: D.P. contributed to the origin of the hypothesis and reviewed, wrote, and edited the manuscript; and G.N. contributed to the generation, review, and editing of the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Dinesh Pendharkar, Bone Marrow Transplant, Cell & Gene Therapy, Sarvodaya Hospital & Research Center, Sector 8, YMCA Rd, Faridabad 121006, Haryana, India; email: drpendharkar@gmail.com.