Key Points

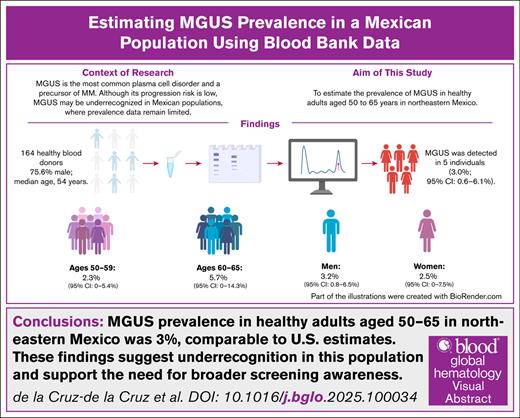

MGUS prevalence was 3% in healthy adults aged 50 to 65 years in Northeastern Mexico.

Preliminary evidence suggests MGUS may be more common in this region, underscoring the need for larger studies.

Visual Abstract

Monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS) is a common plasma cell disorder and precursor to multiple myeloma (MM). While MGUS precedes nearly all MM cases, most individuals remain stable without progression. Its prevalence varies by age, sex, and ethnicity, with lower rates historically reported in Hispanic populations. We aimed to determine MGUS prevalence among adults aged 50 to 65 years in Northeastern Mexico. A cross-sectional study was conducted at a university hospital blood bank between August 2023 and April 2024, including 164 eligible donors (75.6% men; median age, 54 years). Serum electrophoresis and immunofixation identified MGUS in five participants (3.0%; 95% CI, 0.6–6.1). Prevalence was 2.3% in those aged 50–59 and 5.7% in those 60–65. Monoclonal proteins detected included immunoglobulin G (IgG) kappa, IgA lambda, IgM lambda, and IgG lambda. The observed prevalence aligns with U.S. data but exceeds previous Mexican estimates, suggesting MGUS may be underdiagnosed and warranting larger epidemiologic studies.

Introduction

Monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS) is the most common plasma cell disorder and is considered a premalignant condition with a risk of progression to multiple myeloma (MM) or other related plasma cell disorders. MGUS precedes virtually all cases of MM, although it is often undetected before progression.1 It is characterized by the production of an abnormal monoclonal (M) protein, which can be of the immunoglobulin G (IgG), IgA, IgM, or light-chain type, with different progression patterns depending on the immunoglobulin involved. The diagnosis is established by the presence of an M protein spike of <3 g/dL on protein electrophoresis, <10% clonal plasma cells in the bone marrow, and the absence of MM-related organ damage (CRAB symptoms: hypercalcemia, renal failure, anemia and bone lytic lesions).2

MGUS has been identified in ∼1% to 2% of adults in studies conducted in Sweden, the United States, France, and Japan.3-7 The median age at diagnosis is 70 years, and <2% of cases are detected before the age 40 years. Its incidence and prevalence increase with age and are higher in men than in women.8 In Minnesota, the prevalence of MGUS in individuals aged ≥50 years was 3.2%, rising with age and higher in men (4.0% vs 2.7% in women).8,9 MGUS frequency varies by race, being up to 3 times higher in African Americans and twice as high in West African Black men compared to White individuals from Minnesota, suggesting a genetic origin.10,11 Available evidence indicates that MGUS prevalence in Hispanic individuals (0.7%) is lower than that observed in White individuals from Minnesota,12 although more recent data (up to 4%) seem to challenge these findings.13 For this reason, the objective of this study was to determine the prevalence of MGUS in healthy adults aged >50 years in Northeastern Mexico.

Study design

This was a single-center cross-sectional study. Participants were recruited from the blood bank of the Dr. José Eleuterio González University Hospital in Monterrey, Mexico, between August 2023 and April 2024. We included individuals aged >50 years who were accepted as blood donors after routine clinical and laboratory screening at the blood bank. Participants were asked about personal and family history of hematologic malignancies, and individuals with a first-degree relative diagnosed with MM or any other hematologic cancer were excluded from the study. Oral and written informed consent was obtained from all participants. This study was approved by the institutional ethics committee (registration code HE23-00011).

Blood samples (12 mL per participant) were centrifuged for 10 minutes. Serum was divided into 2 aliquots (1 mL and 100 μL) and stored at –30°C until analysis, being thawed at 37°C before processing. All samples underwent protein electrophoresis and agarose gel immunofixation using the Hydrasys 2 Scan Focusing analyzer (Sebia, France).

Participants with the presence of an M protein (detected as a sharp, distinct peak or spike in the gamma or beta region, suggesting the presence of a monoclonal protein, on protein electrophoresis, or as a restriction band by immunoelectrophoresis, interpreted by an expert clinical laboratory chemist and validated by a senior hematologist) were immediately notified by phone and offered an evaluation in the outpatient hematology clinic. The evaluation was focused on screening for monoclonal gammopathy and follow-up clinical significance.

The sample size was calculated to estimate the prevalence of MGUS with a 95% confidence level and a precision of ±3%, assuming an expected prevalence of 4% from a previous pilot study conducted at the same institution (blood donors aged ≥50 years with an M protein) in 2019,13 resulting in a required sample size of 164 participants. To estimate the 95% confidence interval (CI) for the prevalence of MGUS, we used a nonparametric bootstrapping approach with 1000 resamples. Bootstrapping was performed using the bias-corrected and accelerated method in IBM SPSS version 27 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY), which is particularly suitable for small sample sizes and nonnormally distributed data. This method generates multiple resamples with replacement from the original data set, calculates the prevalence in each resample, and then estimates a CI that accounts for bias and skewness in the distribution of the bootstrap estimates.

Results and discussion

A total of 168 donors aged 51 to 65 years were included, of whom 4 were excluded (3 due to hemolysis and 1 due to insufficient sample volume). Of the 164 individuals analyzed, 124 (75.6%) were men, and 40 (24.4%) were women, with a median age of 54 years (interquartile range, 52-59). Of these, 129 (78.7%) were aged 50 to 59 years, and 35 (21.3%) were aged 60 to 65 years. An M protein was identified in 5 patients (3%), 4 detected by electrophoresis and immunofixation and 1 by immunofixation alone. The overall prevalence of monoclonal gammopathy was 3% (95% CI, 0.6-6.1).

The prevalence was 2.3% (95% CI, 0-5.4) in those aged 50 to 59 years and increased to 5.7% (95% CI, 0-14.3) in those aged 60 to 65 years. When stratified by sex, the prevalence was 3.2% (95% CI, 0.8-6.5) in men and 2.5% (95% CI, 0-7.5) in women. Among the 5 identified patients, the M protein types detected were IgG kappa (n = 2), IgA lambda (n = 1), IgM lambda (n = 1), and IgG lambda (n = 1) (Table 1). Four individuals agreed to evaluation. All were asymptomatic with normal physical exploration. In addition to a normal physical examination, general laboratory tests were within normal limits. They were considered low-risk MGUS; therefore, follow-up testing was performed 3 months later to confirm diagnosis.

Characteristics of patients with an identified M protein during screening

| Patient no. . | Sex . | Age, y . | Immunoglobulin . | M protein, g/dL . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | M | 54 | IgG kappa | 0.2 |

| 2 | M | 60 | IgG kappa | 0.6 |

| 3 | F | 51 | IgA lambda | 0.5 |

| 4 | M | 61 | IgM lambda | 0.0 and positive immunofixation electrophoresis |

| 5 | M | 53 | IgG lambda | 0.2 |

| Patient no. . | Sex . | Age, y . | Immunoglobulin . | M protein, g/dL . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | M | 54 | IgG kappa | 0.2 |

| 2 | M | 60 | IgG kappa | 0.6 |

| 3 | F | 51 | IgA lambda | 0.5 |

| 4 | M | 61 | IgM lambda | 0.0 and positive immunofixation electrophoresis |

| 5 | M | 53 | IgG lambda | 0.2 |

F, female; M, male.

This study represents, to our knowledge, the first investigation on the prevalence of MGUS in Northeastern Mexico and the first in over a decade in the country. The prevalence (3%) was observed with wide CIs, which limit the precision of the estimate, but is broadly consistent with that reported in Olmsted County, Minnesota (3.2%).12

Previous studies in Mexico have shown lower MGUS prevalence, such as 0.7% in adults aged >70 years in Puebla, although underdiagnosis is likely due to late incidental detection.12,14 MGUS prevalence is influenced by race, environment, and geography.4 The NHANES 2014 study found rates of 2.3% in White individuals, 3.7% in African Americans, and 1.8% in Mexican Americans, suggesting lower genetic susceptibility in the latter.15,16 In China, the overall prevalence was 2.73%, with 1.16% in those aged 51 to 60 years, similar to Hispanic populations, although possibly underreported.17 Genetic diversity in Mexicans may explain these differences: the population is ∼56% Amerindian, 40% European, and 4% African, with regional variation. The concept of “geographic hematology” reflects the role of genetics in hematologic disease prevalence.16

Although these findings suggest that MGUS may be more prevalent in this region than previously reported in Mexico, the small sample size prevents firm conclusions, and it remains possible that the true prevalence is similar or even lower. Thus, the results should be interpreted as preliminary evidence rather than definitive population estimates.

Currently, population screening for MGUS is not recommended due to the lack of preventive treatment for its progression to MM and the uncertainty regarding survival benefits, because most individuals will never develop MM.18 Some studies in Sweden and the United States have suggested that individuals with prior knowledge of their MGUS may have better outcomes, potentially reflecting closer clinical monitoring rather than a direct effect of early detection.1,19 In Latin America, patients with MM are often diagnosed at a younger median age than those in developed countries,20-22 raising the question of whether earlier identification of MGUS could be relevant; however, this remains speculative and requires further investigation.

Opportunistic screening using protein electrophoresis has been suggested as a useful strategy. In a UK emergency department study, MGUS prevalence was 6.94% in individuals aged >50 years. A significant number of known cases lacked follow-up, highlighting the need for better medical education.23 Although screening asymptomatic individuals may allow for early detection of MGUS or MM, it also poses risks. Psychological distress from diagnosing a premalignant condition with uncertain progression can cause anxiety, reduced quality of life, and unnecessary testing.24,25 The iStopMM study in Iceland screened a large population to assess early detection benefits,26 but it also raised concerns about overdiagnosis, medicalization, and psychosocial effects. In low- and middle-income countries, routine screening may divert resources from more urgent priorities such as infectious diseases, maternal health, or cancers with established high-prevalence screening programs such as breast and cervical cancer. Without evidence of better outcomes, such programs risk low-value care. Thus, although screening high-risk groups may be appropriate, population-wide screening in resource-limited settings should be evidence-based and cautious.24-27

A key limitation of this study is the exclusive recruitment of participants from a blood donor population, which constitutes a highly selected group that may not accurately reflect the general population. Blood donors typically undergo stringent health screening, are more likely to engage in healthy lifestyle behaviors, and tend to have fewer chronic conditions. These factors may introduce selection bias, potentially leading to either underestimation or overestimation of MGUS prevalence. Moreover, individuals with comorbidities or abnormal findings during donor screening are systematically excluded, potentially omitting those at increased risk for monoclonal gammopathies.

An important limitation was the small number of patients with MGUS (n = 5), with only 4 undergoing further evaluation, limiting subgroup analysis and firm conclusions. However, the main objective was to estimate prevalence in a Mexican cohort, a population with limited existing data. The detection of MGUS in apparently healthy donors highlights the possibility of underdiagnosis in Mexico and supports the need for larger, more representative studies to clarify the true prevalence.

In conclusion, this study offers preliminary evidence on MGUS prevalence in healthy adults from Northeastern Mexico. The observed rate of 3.0% (95% CI, 0.6-6.1) is comparable to that in non-Hispanic White individuals. Given the wide CIs, the results should be interpreted cautiously, but they underscore the importance of further research in Mexican and Hispanic populations.

Authorship

Contribution: C.d.l.C.-d.l.C. contributed to formal analysis, visualization, and writing the original draft; J.A.Z.T. contributed to methodology, investigation, data curation, and writing the original draft; O.M.G. and N.C.F. contributed to laboratory analysis, validation, and data interpretation; A.G.-d.L. contributed to writing including review and editing; D.G.-A. contributed to supervision and writing including review and editing; and L.T.-A. contributed to conceptualization, methodology, investigation, project administration, data curation, and writing the original draft.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Luz Tarín-Arzaga, Service of Hematology, Hospital Universitario Dr. José Eleuterio González, Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León, Monterrey, Mexico; email: tarinarzaga@gmail.com.

References

Author notes

Original data are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author, Luz Tarín-Arzaga (tarinarzaga@gmail.com). However, individual participant data will not be shared.