Visual Abstract

Chimeric antigen receptor T-cell (CAR-T) therapy has significantly improved outcomes for patients with hematologic neoplasms, with expanding indications and increasing global use. However, access remains highly unequal across countries. This review outlines the main barriers to CAR-T implementation in resource-limited regions, structured into 4 domains: cost and reimbursement, regulatory frameworks, manufacturing logistics, and clinical infrastructure. The high cost of commercial CAR-T products remains a major limitation, especially in settings where public reimbursement is unavailable and private health care coverage is inconsistent. Academic programs have emerged as alternatives in countries such as Brazil, India, Turkey, and Spain, demonstrating the feasibility of lower-cost, noncommercial production models. Regulatory gaps also contribute to limited access. While high-income countries have developed specific frameworks for advanced therapy medicinal products (ATMPs), many resource-limited regions still lack clear pathways for clinical trials, product approval, or postmarketing surveillance. Brazil stands out for its recent regulatory innovations, including a dedicated resolution for ATMPs and integration with public health care goals. Logistical challenges related to manufacturing capacity, reagent supply, and product-release testing further constrain local implementation. Clinical infrastructure is also insufficient in many resource-limited regions, especially regarding intensive care support, multidisciplinary teams, and access to key medications such as tocilizumab. Ongoing national and regional efforts point to possible strategies for expanding access. These include decentralization of manufacturing, investment in public infrastructure, and regulatory adaptations to support context-specific solutions.

Introduction

Originally conceived within academic institutions, chimeric antigen receptor T-cell (CAR-T) therapy has emerged as a breakthrough for patients with hematologic malignancies.1 Beyond a scientific advancement, it has also challenged oncology paradigms, particularly regarding the integration of novel therapies and the recognition of global health inequities.

The transition of CAR-T production from academia to industry enabled extraordinary progress in this field. A substantial influx of resources, intensive research efforts, and an increasing number of stakeholders have resulted in over 2000 CAR-T clinical trials being registered globally since 2017, most of them in the United States, China, and the European Union (EU).2 The number of commercially available products has also grown; currently, 7 distinct CAR-T therapies have US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval, with indications continually expanding (supplemental Table 1).

CAR-T use is now well established in at least 5 subtypes of non-Hodgkin lymphoma, as well as in acute lymphoblastic leukemia and multiple myeloma.3-11 Indications have progressed to earlier lines of therapy, including upfront settings in high-risk large B-cell lymphoma and ongoing evaluation as alternatives to autologous transplantation in multiple myeloma.12-14 Evidence of clinical benefit has also emerged in relapsed/refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia and in a wide range of immune-mediated disorders, with the potential to broaden CAR-T indications in the near future.15-17

Given these advances, a pressing question remains: why is a cutting-edge therapy not widely accessible worldwide? The United States leads in the number of CAR-T treatments performed. By 2024, the Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research had registered 27 782 patients who had received CAR-T treatment.18 Nevertheless, despite these high numbers, it is estimated that only a minority of CAR-T–eligible patients are ultimately treated, even in the United States.19 In the real-world context, logistical and financial barriers significantly hinder access to this potentially life-saving therapy for many patients.19,20

Across Europe, these obstacles are becoming increasingly evident. As of September 2024, the European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation registry documented over 10 000 CAR-T infusions across >600 centers in 60 countries, mostly in Western Europe.21 Some nations, such as Bulgaria, Latvia, Estonia, and Lithuania, have yet to register any commercial CAR-T use.

In resource-limited regions, data remain scarce. In sub-Saharan Africa, CAR-T is virtually nonexistent, whereas in Southeast Asia and Latin America, access is markedly heterogeneous.22-24 In Brazil, for example, commercial CAR-T products have been approved since 2022, but their use is rare, reflecting systemic barriers in coverage, reimbursement, and infrastructure.25

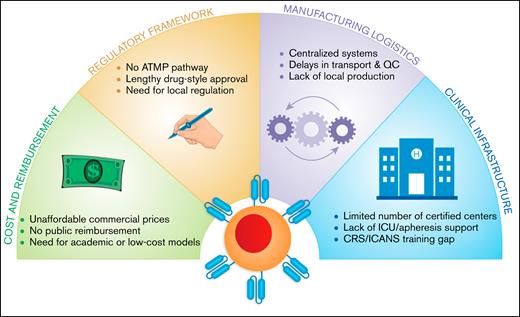

This article provides a global overview of CAR-T access disparities, highlighting emerging solutions in resource-limited settings and the unique innovations from emerging economies. We propose 4 critical domains shaping CAR-T accessibility in constrained environments: cost and reimbursement, regulatory frameworks, manufacturing logistics, and clinical infrastructure (Figure 1).

Key barriers to CAR-T therapy implementation in resource-limited settings. This diagram illustrates 4 major systemic challenges limiting access to CAR-T therapy in low- and middle-income countries. These include: (1) cost and reimbursement, marked by unaffordable commercial pricing, absence of public coverage, and the need for scalable low-cost alternatives; (2) regulatory framework, characterized by the lack of ATMP pathways, prolonged drug-style approvals, and the need for country-specific regulation; (3) manufacturing logistics, characterized by reliance on centralized systems, transport delays, and limited local production capacity; and (4) clinical infrastructure, involving a shortage of certified treatment centers, insufficient ICU/apheresis support, and critical training gaps for toxicity management (eg, CRS, ICANS).

Key barriers to CAR-T therapy implementation in resource-limited settings. This diagram illustrates 4 major systemic challenges limiting access to CAR-T therapy in low- and middle-income countries. These include: (1) cost and reimbursement, marked by unaffordable commercial pricing, absence of public coverage, and the need for scalable low-cost alternatives; (2) regulatory framework, characterized by the lack of ATMP pathways, prolonged drug-style approvals, and the need for country-specific regulation; (3) manufacturing logistics, characterized by reliance on centralized systems, transport delays, and limited local production capacity; and (4) clinical infrastructure, involving a shortage of certified treatment centers, insufficient ICU/apheresis support, and critical training gaps for toxicity management (eg, CRS, ICANS).

Cost and reimbursement

One of the most significant barriers to the widespread adoption of CAR-T therapies is cost. Beyond clinical considerations, these therapies introduce a profound level of economic toxicity, a concept increasingly used in both hematology and oncology to describe the financial burden of high-cost treatments on patients, families, and health care systems.26

Even countries with well-resourced health care systems face significant challenges related to the high cost of CAR-T therapies. In the United States, the price of a single CAR-T infusion is roughly $500 000, excluding additional expenses such as leukapheresis, hospitalization, complication management, and long-term follow-up.27 These cumulative costs may be substantial, as patients often require intensive monitoring, multiple clinic visits, management of late effects, and, in many cases, temporary relocation near treatment centers.28 While some of the acute complications associated with CAR-Ts, such as cytokine release syndrome (CRS), immune effector cell–associated neurotoxicity syndrome (ICANS), and immune effector cell–associated hematotoxicity, are well characterized and routinely addressed, economic toxicity is often underestimated, unanticipated, and may persist long after treatment, emerging as a form of chronic toxicity.

Although discussions about the cost of CAR-T therapy often focus on health care systems and insurance providers, recent evidence shows that it is also a significant burden for patients’ families and caregivers. About 25% of patients in remission continue to experience mild to moderate financial distress, whereas 18% of caregivers have reported moderate to severe hardship even 5 years after treatment.28

In resource-limited regions, the financial burden of CAR-T therapy is exacerbated by systemic gaps, including the lack of public funding mechanisms and inadequate reimbursement practices of private insurers. A Pan-Asian review highlighted the therapy’s prohibitive costs relative to national economic capacity, with some countries reporting price tags as high as 40 to 200 times their per capita gross domestic product, a key benchmark of average income and economic output.22

In Brazil, 4 commercial CAR-T products have been approved by the national regulatory agency (ANVISA) since 2022. However, ∼100 patients have successfully received treatment to date. This stark discrepancy underscores significant structural hurdles within the Brazilian health care system, in which ∼75% of the population depends solely on the public Brazilian Unified Health System (SUS), which currently does not provide reimbursement for CAR-T therapies.29,30 Based on epidemiologic projections and current indications, an estimated 2000 to 3000 patients per year in Brazil could be eligible for CAR-T therapy.31 At current commercial prices, treating this population would require approximately $1.35 billion annually, an amount equivalent to the entire national budget currently allocated to oncology care.32 Even among patients with private insurance, access to CAR-T therapy has been highly restricted, with most treatments granted only through litigation. These protracted legal processes frequently result in substantial delays, with brain-to-vein times, the interval between clinical indication and cell infusion, often exceeding 3 to 4 months.

In response to these access barriers, several countries have established academic or noncommercial CAR-T programs as a strategy to reduce costs and broaden availability. In Spain, for instance, the ARI-0001 product, developed at Hospital Clínic de Barcelona, was approved under the European hospital exemption framework and is offered at roughly one-third the price of commercial alternatives.33 ARI-0001, a CD19-directed CAR-T therapy, has demonstrated safety and efficacy in patients with relapsed or refractory B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia.34,35 Comparable initiatives have been launched in India and Turkey, whereas early-stage programs are emerging in Mexico, Egypt, and South Africa.23,29,36-38

In Turkey, the ISIKOK-19 initiative enabled the development of the country's first locally manufactured CAR-T product, which was administered to patients with B-cell neoplasms in a phase 1 clinical trial.36 The study confirmed the feasibility of local production, with encouraging preliminary results regarding safety and efficacy. In a similar effort, India’s VELCART program produced an anti-CD19 CAR-T product using the CliniMACS Prodigy system.38 The product was evaluated in a real-world clinical setting, with a cost analysis showing significant reductions compared to commercial therapies. These initiatives relied on national infrastructure, public or institutional support, and simplified manufacturing models, demonstrating the potential of noncommercial CAR-T strategies to reduce treatment costs and strengthen regional innovation in biotechnology and autonomy.

A notable example of innovation aimed at cost reduction and public access has emerged in Brazil. The Ribeirão Preto Blood Center, in collaboration with the University of São Paulo, has developed a new academic CD19-directed CAR-T product. Twenty patients were treated through an expanded access program with safety and efficacy results similar to pivotal anti-CD19 CAR-T trials.39 In partnership with the Butantan Institute, a state-owned biotechnology center and the largest vaccine producer in Latin America, and with funding from the Brazilian Ministry of Health, a phase 1/2 clinical trial is currently underway (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT06101381).40 Although still under clinical investigation and not yet commercially available, preliminary estimates suggest that the academic CAR-T may cost approximately one-fifth of commercial products in Brazil, underscoring its promise to expand access. The ultimate goal is to obtain regulatory approval and incorporate this more affordable therapy into the SUS, making it available to other public hospitals nationwide. In Mexico, the academic development of an anti-CD19 CAR-T product is also underway, with clinical trials awaiting regulatory authorization as of 2025.23 Together, these efforts reflect a broader regional movement toward the creation of sustainable, locally adapted CAR-T platforms across Latin America.

Beyond institutional innovations, the development of off-the-shelf allogeneic CAR-T and chimeric antigen receptor-engineered natural killer (CAR-NK) therapies represents a promising strategy to reduce manufacturing costs, shorten vein-to-vein times, and improve scalability.41-43 Unlike autologous products, which require individualized manufacturing for each patient, allogeneic platforms utilize donor-derived cells that can be produced at scale, cryopreserved, and distributed on demand. In academic and point-of-care settings, these approaches could support decentralized manufacturing and enable treatment of multiple patients from a single batch, whereas gene-editing strategies are employed to mitigate host-versus-graft rejection and graft-versus-host disease, making them an increasingly attractive option for academic networks in resource-limited settings.44

Regulatory framework

Unlike conventional pharmaceuticals, CAR-T therapies are classified as advanced therapy medicinal products (ATMPs) due to their use of living cells that undergo ex vivo genetic modification.45 Their inherently complex and individualized nature demands a dedicated regulatory model for assessment, manufacturing, approval, and posttreatment surveillance. These therapies defy traditional categorizations of drugs or biologics, often challenging established standards of quality control, pharmacovigilance, and compliance with good manufacturing practices (GMP).

In high-income countries, agencies have taken concrete steps to build regulatory structures tailored to ATMPs. The FDA, through its Office of Therapeutic Products, provides oversight for gene-based and cell-based products and has issued specific guidance documents for developers.46 In the EU, the European Medicines Agency created a dedicated ATMP regulation, enabling centralized product evaluation.47 A key feature of the EU system is the hospital exemption (HE) mechanism, which allows noncommercial, patient-specific products to be used in accredited centers under national supervision, bypassing centralized approval when appropriate.

The ARI-0001 CAR-T program in Spain is a leading example of how the HE mechanism can enable academic innovation.33 Switzerland, while not employing a formal HE, has a more permissive regulatory model that allows hospital-based CAR-T programs under a national regulatory system. Institutions must meet infrastructure and accreditation criteria and negotiate directly with manufacturers.48

Japan represents another key model of regulatory innovation. Through the Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency, the country established in 2014 a distinct framework for regenerative and cell-based therapies. This includes conditional and time-limited approval pathways, enabling earlier patient access while requiring long-term follow-up and real-world evidence collection. This system has accelerated the clinical adoption of ATMPs, positioning Japan as a pioneer in balancing innovation with postmarketing safety obligations.49

By contrast, many resource-limited regions still lack specific regulatory pathways for cell and gene therapies. The absence of clear classification criteria, evaluation guidelines, or infrastructure for GMP oversight often results in delayed trial approvals and uncertain standards for clinical use. Even when technical capacity exists within academic institutions, regulatory gaps can be a major barrier to local development and sustainable implementation.

In this scenario, Brazil stands out as a model of regulatory innovation tailored to the realities of emerging economies. In 2020, ANVISA issued its first national resolution specific to ATMPs, outlining detailed requirements for manufacturing, preclinical and clinical development, traceability, and pharmacovigilance.49,50 Building upon this regulatory foundation, ANVISA launched a public call in 2023, inviting developers of advanced therapies to collaborate in pathways aimed at integration into the SUS, signaling a national commitment to fostering local innovation and ensuring equitable access to complex treatments.51 Brazil’s CAR-T initiatives reflect a uniquely coordinated academic-regulatory public investment model, combining scientific leadership with policy adaptation, positioning the country as a benchmark for other emerging economies striving to incorporate cellular therapies into their public health agendas.52

Other Latin American countries are also beginning to adapt their regulatory environments for ATMPs, although progress remains uneven. In Mexico, CAR-T therapies are still evaluated under conventional drug pathways, but recent reforms have created specific routes for assessment, such as scientific advice and expedited reviews, signaling a national effort to broaden patient access.53 Argentina currently classifies ATMPs, including stem cell products, as biologicals requiring formal registration, although harmonization and clarity of implementation remain limited.54 Chile, Ecuador, and Peru remain in early stages, with limited clinical use and no approved ATMPs.54 A similar scenario is seen in South Africa, where ATMPs are still regulated as conventional medicines, with only gradual movement toward more specific oversight.49 Together, these examples highlight both the opportunities and persistent gaps in regulatory readiness across the Global South.

Manufacturing logistics

Manufacturing CAR-T therapies is a highly complex and resource-intensive process. Traditional autologous production involves multiple manual steps, including leukapheresis, T-cell activation, genetic modification, expansion, and quality control, each requiring specialized equipment, trained personnel, and strict adherence to GMP standards.55 These steps are time consuming, prone to batch-to-batch variability, and susceptible to contamination, all of which contribute to high production costs and inconsistent product quality.

In resource-limited regions, these challenges are further compounded by structural constraints. Even in nations that have established local production capacity, there remains a strong dependence on imported reagents, which substantially increases production costs and undermines autonomy. Viral vectors, in particular, are among the most highly demanded inputs globally, leading to supply bottlenecks and delays due to complex importation procedures.56 In addition, the infrastructure required to sustain GMP-compliant manufacturing (cleanrooms, automated platforms, and validated testing procedures) is often limited to a few academic or research centers in large metropolitan areas.

In Brazil, a national strategy was developed to address these challenges through a collaborative model. Rather than replicating industrial-scale infrastructure, the country leveraged the manufacturing expertise of the Butantan Institute and the translational research experience of the Ribeirão Preto Blood Center and the University of São Paulo. This effort culminated in the establishment of the Advanced Cell Therapy Nucleus (Nutera), a dedicated facility with an estimated annual capacity of 600 CAR-T products. While this initiative represents a major advance in local production, it still falls short of projected national demand and continues to rely on imported reagents.

Geography also plays a key role. In large or logistically complex countries, transporting leukapheresis material to centralized manufacturing facilities and returning the final product to the treatment center pose major cost and timing challenges. Median vein-to-vein times (V2Vt) for FDA-approved CAR-T products typically range from 30.6 to 48.4 days and may be even longer in resource-limited regions due to additional barriers such as customs clearance, cold-chain limitations, and transportation delays. In real-world settings, prolonged V2Vt has been associated with inferior clinical outcomes.23,57 Patients with V2Vt exceeding 40 days are more likely to require bridging therapy, an intervention that, although often necessary, may further postpone CAR-T infusion and increase the risk of organ-specific toxicities that compromise subsequent treatment tolerance. Moreover, extended V2Vt has been linked to lower complete response rates, decreased overall survival, and a higher incidence of postinfusion thrombocytopenia, suggesting broader implications for hematologic recovery and the overall safety profile.57

To address these limitations, decentralized (point-of-care) manufacturing has been suggested as a potential strategy. By enabling local production within or near treatment centers, this model can reduce transportation time and cost, streamline logistics, and promote regional self-sufficiency. However, decentralized systems face barriers related to regulatory harmonization, quality-control standardization, and scalability. Many regulatory agencies require individual approval for each production site, and ensuring consistency across multiple manufacturing units remains a major technical challenge.58

A final hurdle is product-release testing. Sterility, identity, potency, and replication-competent virus assays are critical for ensuring safety but are often difficult to perform outside of high-throughput reference laboratories.59 In resource-limited regions, a lack of access to validated assays and qualified personnel can delay batch release, creating additional bottlenecks. Innovative approaches such as automated closed systems, faster pathogen-detection technologies, and nonviral gene transfer are under active development to reduce production time and improve reliability.

Ultimately, building sustainable CAR-T manufacturing capacity in resource-limited settings will require a combination of strategies: investing in regional infrastructure, fostering public-academic partnerships, promoting local reagent development, and adapting regulatory pathways to support innovation while safeguarding patient safety and product quality.

Clinical infrastructure

The successful implementation of CAR-T therapies also hinges on the availability of robust clinical infrastructure. As a baseline requirement, institutions administering these therapies must fulfill standards comparable to those required for hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT), including access to apheresis units, cryopreservation facilities, intensive care units (ICUs) (up to one-third of patients may need ICU admission),60 and interdisciplinary teams capable of managing acute toxicities, such as CRS and ICANS, which are virtually present in all treated patients.61,62

This requirement, although frequently underappreciated, is particularly critical in resource-limited regions, where most hospitals lack the infrastructure to deliver complex cellular immunotherapies. In 2022, Brazil reported ∼4000 HSCT procedures, with most concentrated in the South and Southeast regions.63 Until recently, the North region had no HSCT centers, highlighting persistent regional disparities in access to specialized care.63,64 In addition, transplant services remain unevenly distributed between the public and private health care sectors. If CAR-T therapies were to be implemented at scale, treating 2000 to 3000 patients per year could demand up to 50% of the country’s existing HSCT infrastructure, particularly in terms of bed capacity, continuous monitoring, and availability of dedicated and trained multidisciplinary teams.

Bed capacity is therefore an additional limitation, as most patients still require inpatient monitoring during the high-risk period for CRS and ICANS. In high-income countries, pilot programs have begun to evaluate the feasibility of outpatient CAR-T administration, with encouraging early safety data.65 However, such an approach would be difficult to implement in resource-limited regions, where limited emergency support, insufficient housing options for temporary relocation, and irregular access to critical medications pose significant challenges.

These constraints are not unique to Brazil. A recent regional report from Asia underscored that only a limited number of centers currently meet the minimum criteria for CAR-T therapy administration, primarily due to deficiencies in clinical preparedness and supportive care infrastructure.22 Similar limitations have been documented across Africa, where transplant programs remain either in their infancy or are highly centralized, leaving large segments of the population without access to cellular therapies. Notably, only 6 of 54 African countries have HSCT programs officially recognized by the Worldwide Network for Blood and Marrow Transplantation, emphasizing the magnitude of infrastructural inequity across the continent.24

Equally concerning is the inconsistent availability of essential supportive care medications. Tocilizumab, an interleukin-6 receptor antagonist used as first-line therapy for CRS, is frequently either unavailable or unaffordable in many resource-limited regions. Alternative agents such as anakinra and siltuximab, used in cases of refractory CRS or ICANS, are often not approved for use or are prohibitively expensive in most countries.

To address these challenges, comprehensive and coordinated strategies are needed to strengthen clinical infrastructure for cellular therapy. Professional societies play a key role in developing consensus-based guidelines that define minimum standards for safe CAR-T delivery, including ICU readiness, pharmacy protocols, and adverse event management. In the US, the American Society for Transplantation and Cellular Therapy has published widely adopted consensus grading systems for CRS and ICANS, which form the basis for toxicity recognition and treatment.66 In Europe, the European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation and the European Hematology Association released a comprehensive CAR-T Handbook, outlining structural, logistical, and training requirements for accredited centers.67 In Brazil, the Brazilian Association of Hematology, Hemotherapy, and Cell Therapy issued a national consensus on the structuring of CAR-T centers, offering context-specific guidance on multidisciplinary team organization, center eligibility, and access to supportive care.68 Together, these efforts illustrate how scientific societies can guide safe and scalable implementation, even in resource-constrained settings.

Furthermore, structured training programs can help expand the pool of qualified professionals capable of delivering and supporting cellular therapies. National health authorities and transplant societies can further contribute by creating incentives to expand the network of accredited HSCT centers and to integrate CAR-T capabilities into existing transplant programs whenever feasible. Without deliberate investments in infrastructure, even the most effective CAR-T products will remain inaccessible to most patients in resource-limited regions.

Conclusion

Expanding access to CAR-T therapy in resource-limited regions will require targeted and coordinated actions. Cost remains the primary barrier, but solutions exist. Academic manufacturing programs, public investment, and simplified production models have already demonstrated feasibility in countries like Brazil, India, and Turkey.

To scale these efforts, governments must prioritize the inclusion of CAR-T therapies in national health care strategies. This includes allocating public funding, fostering regulatory pathways adapted to advanced therapies, and incentivizing local production and innovation. Regional cooperation, particularly for technology transfer and shared-reagent supply, can reduce dependency on imported inputs and lower costs.

Existing transplant centers should be leveraged as hubs for CAR-T delivery, with investments in training, ICU support, and access to essential medications like tocilizumab. Regulatory agencies must also streamline approval processes for both commercial and noncommercial products, enabling faster translation from research to patient care.

CAR-T access in resource-limited regions will require deliberate planning, sustained funding, and alignment across academic, regulatory, and clinical sectors. Without this, the gap in access will continue to widen as indications for CAR-T therapy expand, particularly with the imminent incorporation of T-cell therapies into solid tumors, which will dramatically increase patient demand and resource requirements.

At the same time, ongoing scientific and technological advances are likely to facilitate this process. Developments in allogeneic CAR platforms, expanded automation across the entire manufacturing chain, approaches that shorten production time and optimize the use of key resources, and strategies to mitigate toxicity and improve safety all hold promise to make CAR-T therapies less costly, more practical, and safer to deliver.69-71 When combined with regional cooperation and knowledge transfer, these innovations provide a realistic pathway toward broader, sustainable, and equitable global access.

Authorship

Contribution: All authors designed and performed the research, wrote the manuscript, and reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Diego V. Clé, Hemocentro de Ribeirão Preto, Rua Tenente Catão Roxo, 2501, Ribeirão Preto, São Paulo 14051-140, Brazil; email: diegovc@usp.br.

References

Author notes

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.