Key Points

Low-dose nivolumab is adequate for complete PD-1 RO on T cells, and persists beyond recommended dosing time points.

Low-dose nivolumab has clinical efficacy in Hodgkin lymphoma and is a cost-effective alternative to standard dosing.

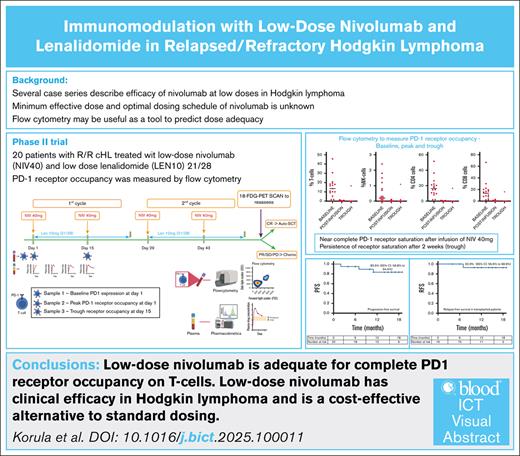

Visual Abstract

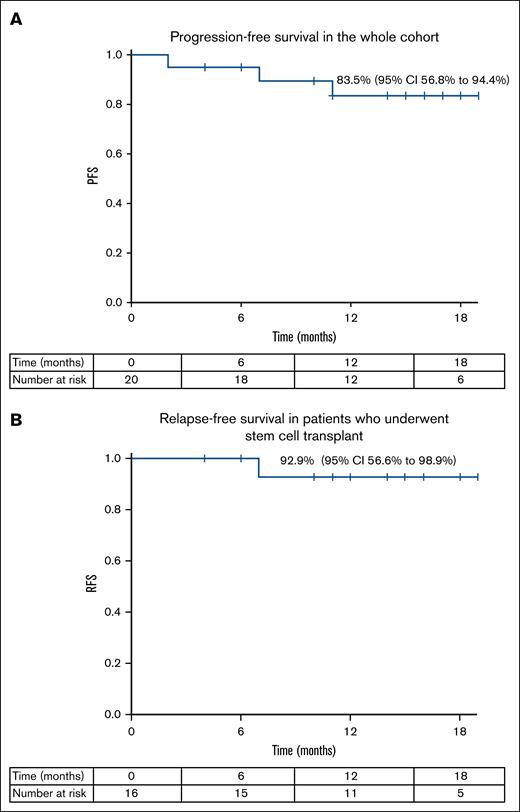

Based on previous reports of the efficacy of low-dose nivolumab, we hypothesized that a flat 40 mg nivolumab would be adequate to saturate available programmed-cell death protein-1 (PD-1) receptors on circulating T cells, and would show clinical efficacy in relapsed/refractory (R/R) Hodgkin lymphoma (cHL). This single-arm trial enrolled 20 patients with R/R cHL. Patients received nivolumab 40 mg every 2 weeks (NIV40) with lenalidomide 10 mg (21/28) (LEN10). PD-1 receptor occupancy (RO) was analyzed by flow cytometry. Plasma drug levels were measured at 4 time points. Response was assessed after 4 doses of nivolumab. Median dose of nivolumab was 0.7 mg/kg (range, 0.4-0.8). Twelve patients (60%) had a complete response, and 6 (30%) had a partial response. In patients undergoing autologous stem cell transplant, a median CD34 dose of 11.7 × 106 per kg (range, 3.9-26.5) was achieved with granulocyte-colony stimulating factor mobilization. Progression-free survival for the whole cohort was 83.5% (95% confidence interval [CI], 56.8-94.4), and relapse-free survival in patients who underwent transplant was 92.9% (95% CI, 56.6-98.9) (Median follow-up 15 months (range 10.5-22.4)). One hour after the first NIV40 infusion (peak), complete PD-1 RO was noted, and at 14 days after infusion (trough), CD8+ T cells showed full RO (P = 0.611). Simple linear regression did not identify sex, age, creatinine, or body weight as factors influencing the AUCtau. Immunomodulation with NIV40-LEN10 is effective in R/R cHL. Flow cytometry for PD-1 RO should be studied as a potential biomarker to guide dosing, leading to rationalized use of PD-1 inhibitors. This trial was registered at Clinical Trial Registry of India as #CTRI/2022/04/042179.

Introduction

Over the last decade, immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) have altered the landscape of oncology. Pertinent but unanswered questions of both clinical and economic relevance include the minimum effective dose, the optimal dosing schedule, and the number of doses required for clinical benefit,1,2 and answers to these questions hold relevance not only for lower- and middle-income countries, but also for more advanced healthcare settings. Supported by the lack of a dose-response relationship in phase 1/2 trials, and driven by economic realities and accessibility issues,3 nivolumab is being increasingly used at doses lower than the United States Food and Drug Administration-approved 3 mg/kg in lower- and middle-income countries, and clinical efficacy with lower doses has been demonstrated in a wide range of malignancies.4-7

Approved dose and scheduling of monoclonal antibody therapy are extrapolated from pharmacokinetic methods that are more suited to conventional chemotherapy, where toxicity is dose-limiting.8 Because monoclonal antibodies and targeted therapies have fewer off-target effects, they are better tolerated than conventional chemotherapy, and phase 1/2 trials that focus on toxicity result in approval for the highest tolerated dose, rather than the lowest effective dose.2,8,9 Programmed-cell death protein-1 (PD-1) inhibitors are unique in their mechanism of action, with the intended target being not the tumor cell but the cognate receptors on circulating T cells, which are easily accessible for sampling. This provides opportunities to study the adequacy of dosing as well as drug persistence, leading to a shift away from using pharmacokinetic algorithms for these drugs.

We designed a phase 2 trial with a chemotherapy-free regimen using immunomodulation at first relapse or progression of classical Hodgkin lymphoma (cHL) with low-dose checkpoint inhibition to improve remission rates with minimal toxicity and cost. Because the dose of nivolumab was a fixed 40 mg (NIV40), which is significantly lower than the standard 240 mg, a second agent lenalidomide (LEN10) was used as combination therapy. Lenalidomide was chosen in view of its pleiotropic mechanism of action with immunomodulatory and antineoplastic effects. There are reports of the efficacy of lenalidomide as a single agent in relapsed and refractory (R/R) cHL.4,10,11 There are also early phase data on the combination of lenalidomide and check-point inhibition,12,13 with modest benefits. Flow cytometric testing for PD-1 receptor occupancy (RO) was designed to provide data on dose adequacy and drug persistence to move towards a more rationalized dosing of anti-PD-1 monoclonal antibody therapy.

Methods

Patients aged ≥18 years with a World Health Organization diagnosis of biopsy-proven cHL with primary progressive disease (after completion of the ABVD regimen [adriamycin, bleomycin, vinblastine, and dacarbazine] or at first relapse [after having a documented complete remission after ABVD]) were eligible for the study. Additional inclusion criteria were as follows: Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status of 0 to 2, adequate renal (serum creatinine ≤1.5 times the upper limit of normal), hepatic (bilirubin ≤2.0 mg/dL and aspartate aminotransferase/alanine aminotransferase ≤3 times the upper limit of normal), and cardiac (echocardiography with ejection fraction >50%) function. Patients who had a history of autoimmune disease, or patients who were pregnant or nursing were not eligible.

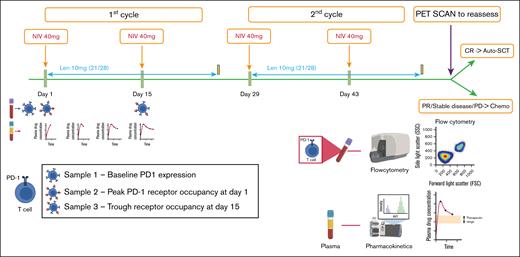

Study design and treatment

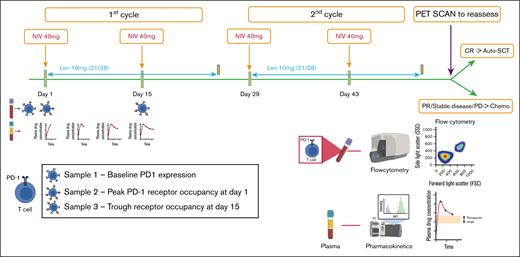

This was an open-label, single-arm, single-center, phase 2 trial. Two cohorts were initially planned for enrollment – transplant-eligible and transplant-ineligible. The protocol comprised of nivolumab at a fixed 40 mg dose (NIV40) on days 1 and 15 (Figure 1) in a 28-day cycle. In a protocol modification prior to the first enrolled patient, lenalidomide (LEN10) was added to the treatment regimen at a fixed dose of 10 mg from day 1 to 21 of the 28-day cycle. Patients ineligible for transplant were planned for a 2-year maintenance with lenalidomide (LEN10 for day 1 to 21 in a 28-day cycle); however, due to poor enrollment, recruitment was halted in patients ineligible for transplant. Dose reductions of lenalidomide for cytopenia were at the physician’s discretion. Growth factors were not administered routinely, but were given as clinically indicated for neutropenia at the physician’s discretion. Immune-related adverse events (iRAEs) were recorded based on symptomatology, and additional tests were not performed for iRAE monitoring, unless clinically indicated.

Trial schema for treatment protocol and sampling for PD-1 RO and pharmacokinetics. Each cycle lasted 28 days and comprised 2 infusions of nivolumab at a fixed 40 mg dose (NIV40) on days 1 and 15, and lenalidomide (LEN10) at a fixed dose of 10 mg from day 1 to 21. Samples for RO were collected at the following time points: before infusion of nivolumab (baseline PD-1 receptor status), 1 hour after infusion of first dose of nivolumab (peak PD-1 RO), and before infusion of second dose of nivolumab (trough PD-1 RO). For pharmacokinetics, plasma samples were obtained during the first cycle of therapy at the following time points: 1 hour after infusion of first dose of nivolumab (peak drug level), 5 days after infusion, 10 days after infusion, and at 14 days (before infusion of second dose of nivolumab, ie, trough drug level). Patients were re-assessed with FDG-PET 4 weeks after the fourth dose of nivolumab. CR, complete response; PR, partial response; PD, progressive disease.

Trial schema for treatment protocol and sampling for PD-1 RO and pharmacokinetics. Each cycle lasted 28 days and comprised 2 infusions of nivolumab at a fixed 40 mg dose (NIV40) on days 1 and 15, and lenalidomide (LEN10) at a fixed dose of 10 mg from day 1 to 21. Samples for RO were collected at the following time points: before infusion of nivolumab (baseline PD-1 receptor status), 1 hour after infusion of first dose of nivolumab (peak PD-1 RO), and before infusion of second dose of nivolumab (trough PD-1 RO). For pharmacokinetics, plasma samples were obtained during the first cycle of therapy at the following time points: 1 hour after infusion of first dose of nivolumab (peak drug level), 5 days after infusion, 10 days after infusion, and at 14 days (before infusion of second dose of nivolumab, ie, trough drug level). Patients were re-assessed with FDG-PET 4 weeks after the fourth dose of nivolumab. CR, complete response; PR, partial response; PD, progressive disease.

Response criteria

Responses were assessed by fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) after 2 cycles of therapy using the Lugano criteria and LYRIC assessment scores. The primary end point of the study was the complete metabolic response rate (Deauville score [DS]1-3). Patients who had a DS of 4 after 2 cycles were permitted 1 additional cycle of therapy before a second reassessment. The secondary end points were overall response rate (ORR), progression-free survival (PFS; defined as disease progression [DS5 with biopsy-proven disease], relapse, or death), and relapse-free survival (defined as relapse or death).

PD-1 RO studies

Nivolumab binding to PD-1 on T cells with strong affinity masks the flow cytometric detection of PD-1 by anti-PD-1 monoclonal antibody (CD279: clone EH12.1).14 Having previously standardized the PD-1 RO assay using a fluorescence minus-one (FMO) and internal controls, and increasing in vitro dilutions of nivolumab in normal controls (supplemental Figure 1A), we used the same procedure in this study for immunophenotypic characterization of PD-1 receptor expression and occupancy as a measure of dose adequacy.

A total of 4 samples were collected, at the following time points: before infusion of nivolumab (baseline PD-1 receptor status), 1 hour after infusion of first dose of nivolumab (peak PD-1 RO), and before infusion of second dose of nivolumab (trough PD-1 RO; Figure 1). Samples at each time point were collected in heparin tubes and immediately processed using the Stain-Lyse-Wash method. The cocktail of antibodies used for the incubation was as follows: CD4 (fluorescein isothiocyanate [FITC]), CD8 (phycoerythrin [PE]), CD3 (peridinin-chlorophyll-protein complex-cyanine 5.5 [PerC P-Cy5.5])), CD279 (phycoerythrin-cyanine 7 [PE-Cy7]), CD56 (allophycocyanin [APC]), CD45 (allophycocyanin - hilite 7 [APC-H7]), CD27 (V450), CD45RA (V500). The antibody cocktail was then incubated with the samples for 10 minutes. Another tube with the same panel, except for CD279 (FMO control), was processed in parallel. After processing, samples were acquired in a BD FACSCanto instrument and analyzed using BD FACSDiva software (representative image from patient 3 shown in supplemental Figure 1B).

Pharmacokinetic studies

Plasma samples were obtained during the first cycle of therapy at the following 4 time points: 1 hour after infusion of first dose of nivolumab (peak drug level), 5 days after infusion, 10 days after infusion, and at 14 days (before infusion of second dose of nivolumab; Figure 1). Plasma was immediately processed, aliquoted, and frozen at –70°C for subsequent analysis of plasma drug levels. Nivolumab levels were measured using KRIBIOLISA Nivolumab (OPDIVO) enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kit (Krishgen Biosystems, India) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. A noncompartmental analysis was performed to determine the elimination rate constant (ke), volume of distribution (Vd), and AUCtau (interdose area under the curve). The elimination rate constant (ke) is the slope of the regression line between log concentrations and time in hours. The formulas used to estimate the pharmacokinetic parameters were as follows:

Simple linear regression was performed to identify factors that could influence AUCtau. Simple logistic regression was performed to determine the influence of systemic exposure as AUCtau, and elimination rate constant on the clinical outcome.

Statistical analysis

A sample size of 20 in the transplant-eligible cohort was required, based on an α of 0.10 and a power of 0.9 to detect a target complete response (CR) rate of 80%, compared with a CR rate of 40% with conventional salvage therapy. Continuous variables were summarized as mean/standard deviation (SD) or median/range depending on the normality of distribution. Categorical variables were expressed in frequencies and percentages. Differences in continuous variables between different groups were analyzed by either Student t test (if parametric distribution) or Mann-Whitney U test (if nonparametric distribution). Differences in categorical variables were compared using Fisher exact test or χ2 test. PFS was defined as the time from enrollment to the date of progression, relapse, death, or date of last follow-up. Statistical analysis was performed with IBM SPSS Statistics Version 23. Graphical analysis using box-whisker (Tukey) plots was performed using the Prism Version 5.00 software (GraphPad). The CR and ORR were calculated along with 95% confidence interval (CI), and Kaplan-Meier analysis was used to estimate PFS and relapse-free survival. The cut-off for follow-up data was 31 December 2024.

The study protocol was approved by the institutional review board, and adverse events were overseen by the institutional Data Safety Monitoring Board. The study was registered with the Clinical Trials Registry of India (CTRI/2022/04/042179), and conducted in accordance with Good Clinical Practice guidelines. All the patients provided written informed consent in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Results

From May 2022 to March 2024, 35 patients with R/R Hodgkin lymphoma who were eligible for transplant were screened for study eligibility, of whom 20 consented to participate in the study. The median patient age was 30 years (range, 18-66). Five (25%) patients had stage I/II disease, and 15 (75%) patients had stage III/IV disease. Eight patients (40%) were in first relapse, 11 (55%) had primary progressive disease, and 1 had relapsed after autologous transplant (enrolled in error but continued the study protocol). The median patient weight was 54 kg (range, 47-86), and median dose of nivolumab delivered was 0.7 mg/kg (range, 0.4-0.8). The key patient characteristics are listed in Table 1.

Treatment responses

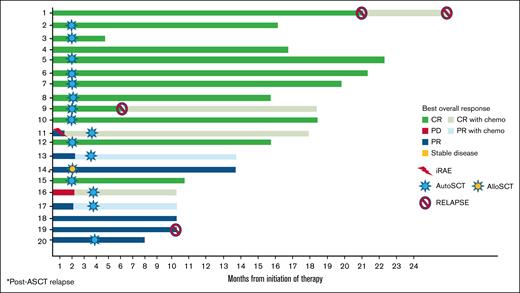

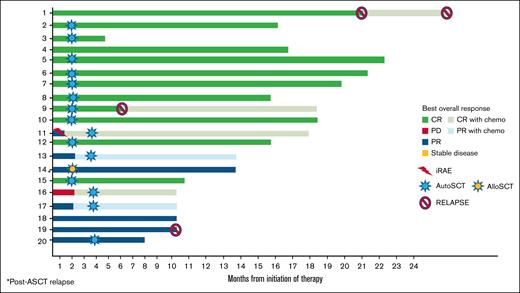

The treatment responses after 2 cycles of the study protocol as well as subsequent therapies are shown in Table 1 and Figure 2.

Treatment response to the NIV40-LEN10 study protocol and outcomes, including iRAEs, salvage therapy with gemcitabine, cisplatin, and dexamethasone, AutoSCT, and AlloSCT. AlloSCT, allogeneic stem cell transplant; AutoSCT, autologous stem cell transplant; PD, progessive death.

Treatment response to the NIV40-LEN10 study protocol and outcomes, including iRAEs, salvage therapy with gemcitabine, cisplatin, and dexamethasone, AutoSCT, and AlloSCT. AlloSCT, allogeneic stem cell transplant; AutoSCT, autologous stem cell transplant; PD, progessive death.

After 2 treatment cycles, patients were reassessed with 18-FDG-PET/computed tomography, with a median time to reassessment of 29 days (range, 14-47) after the fourth dose of nivolumab. Nineteen patients completed treatment as per protocol, and 1 patient was taken off-trial due to a grade 2 iRAE. In the intention-to-treat analysis, 12 out of 20 patients (60%) had a CR (DS1-3), and 4 (20%) had a partial response (PR; DS4). Of the 3 patients with stable disease (DS5), 2 patients had only focal FDG-avidity, and 1 month later without further therapy, and repeat FDG-PET showed a DS4 (response to treatment was therefore recorded as a PR), with a total of 6 patients out of 20 showing a PR. Two patients with DS4 (PR) received 1 further cycle of therapy (2 doses of NIV40 and 21 days of LEN10) and were reassessed, with no change in the response. The ORR (CR + PR in 18/20) was 90% (95% CI, 0.68-0.98).

Four out of 20 patients (2 PR, 1 with stable disease, and 1 patient with iRAE) underwent salvage therapy with gemcitabine, cisplatin, and dexamethasone, of whom 2 remained in PR and 2 achieved CR.

Adverse events

Of the 20 patients enrolled in the study, 1 developed a grade 2 iRAE (acute demyelinating polyneuropathy) after 2 doses of nivolumab and was taken off the study protocol. Three patients had grade 1 anemia; none had thrombocytopenia or neutropenia, and there were no lenalidomide dose reductions for cytopenia, except for patient 1 who presented with pancytopenia due to marrow involvement (full dose was given from the second cycle onwards). None of the patients had received granulocyte-colony stimulating factor. On follow-up, 2 patients developed hypothyroidism (grade 1), and 1 developed adrenal insufficiency (grade 2).

ASCT

Fifteen patients underwent autologous stem cell transplant (ASCT) (11 patients after 2 cycles of the study protocol [10 in CR, 1 in PR], 4 after salvage chemotherapy [2 in CR and 2 in PR]). Four patients did not undergo ASCT due to financial constraints (2 in CR and 2 in PR), of whom 2 subsequently had relapse of disease. One patient underwent allogeneic stem cell transplant in PR (patient 14, treated after ASCT relapse).

In the 11 patients who underwent ASCT after the study protocol, as per institutional protocol, stem cells were mobilized with granulocyte-colony stimulating factor only (5 μg/kg twice daily for 4 days). Two patients required 2-day apheresis (1 received plerixafor). All patients had adequate stem cell mobilization, with a mean CD34 dose of 11.7 × 106 per kg (range, 3.9-26.5).

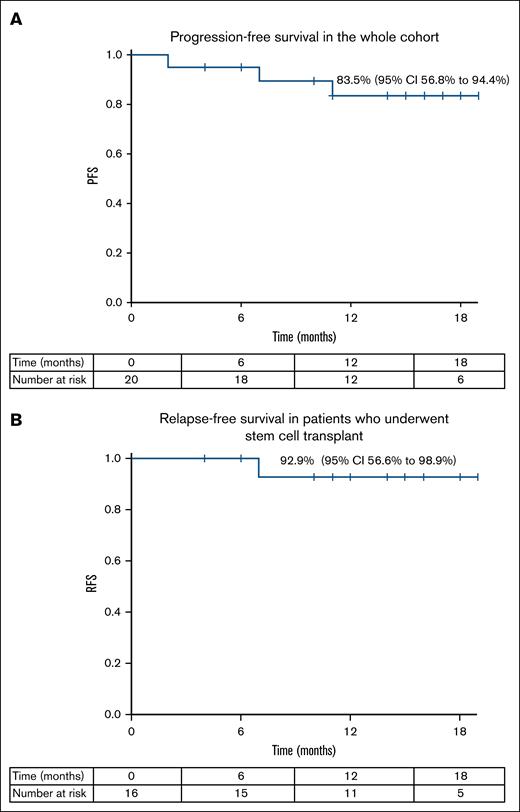

The 1-year PFS rate for the whole cohort was 83.5% (95% CI, 56.8-94.4), with a relapse-free survival rate of 92.9% (95% CI, 56.6-98.9) in patients who underwent stem cell transplant, with a median follow-up of 15 months (range, 10.5-22.4; Figure 3).

Clinical outcomes following treatment with the study protocol. (A) Progression-free survival in the whole cohort. (B) Relapse-free survival in patients who underwent stem cell transplant.

Clinical outcomes following treatment with the study protocol. (A) Progression-free survival in the whole cohort. (B) Relapse-free survival in patients who underwent stem cell transplant.

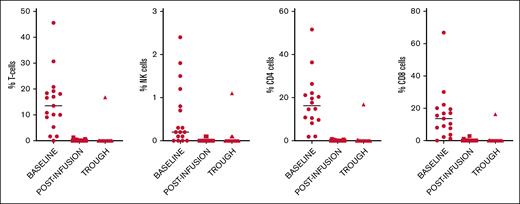

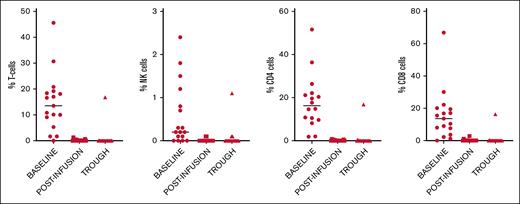

Receptor occupancy

Immunophenotypic characterization of PD-1 receptors at baseline, after first infusion, and prior to second infusion is shown in Table 1. The percentage of PD-1+ cells in the various subsets (T cells, natural killer cells, CD4+ and CD8+ T cells) at baseline, after infusion of NIV40 (peak), and at 14 days after infusion (trough) are shown in Figure 4.

Immunophenotypic characterization of baseline PD-1 receptor expression in T-cell subsets and natural killer (NK) cells, and available PD-1 receptors at 1 hour after infusion (peak) and 14 days after infusion (trough) after NIV40.

Immunophenotypic characterization of baseline PD-1 receptor expression in T-cell subsets and natural killer (NK) cells, and available PD-1 receptors at 1 hour after infusion (peak) and 14 days after infusion (trough) after NIV40.

Compared with the FMO negative control, the median percentage of cells positive for PD-1 within the CD8+ T-cell subset was 13.6% (range, 1.2%-66.8%), with a wide range of expression within the CD8+ subset signifying significant interpatient variation in baseline PD-1 expression (mean, 15.8%; SD, 15.3).

After the first NIV40 infusion (peak), complete PD-1 RO was observed, with almost no CD8+ T cells with PD-1 positivity above the FMO control (median 0% [range, 0-2.8]). At the trough time point, there was no significant difference in the number of CD8+ T cells showing full RO compared with that at the peak time point (P = .611). Only 1 patient showed a loss of RO to 46% in CD8+ T cells at the trough time point. This patient subsequently developed grade 2 iRAE after the second dose of NIV40 and was taken off the trial.

Pharmacokinetics

The mean (SD) AUCtau, ke, half-life, and Vd were 1955.90 mg/h per L (569.71), 0.004 h−1 (0.001), 205.3 hours (65.4), and 4.23 L (1.70), respectively. The interindividual variations calculated as coefficient of variation (CV%) were 29.12, 33.58, 31.85, and 40.22 for AUCtau, ke, half-life, and Vd, respectively (per-patient data for half-life are shown in Table 1). Simple linear regression did not identify sex, age, serum creatinine, creatinine clearance calculated using the Cockcroft Gault equation, or body weight as significant factors influencing AUCtau. Simple logistic regression did not identify AUCtau or elimination rate constants as factors influencing clinical outcomes.

Discussion

Although ICIs have changed the landscape of therapy in upfront and relapsed Hodgkin lymphoma, several important questions remain unanswered, including the optimal dose for the clinical effect, optimal number of doses, and dosing frequency. Key phase 1 trials with the PD-1 inhibitor MDX-1106 in solid organ malignancies,15 and the Checkmate phase 1 trial in R/R Hodgkin lymphoma16 focused primarily on tolerability, leading to 3 mg/kg being tested in expansion cohorts. Importantly, in both trials, though a dose-response relationship was not established, due to tolerability as well as efficacy, nivolumab is approved at a dose of 3 mg/kg (or 240 mg as a flat dose) every 2 weeks, in all tumor types. A lack of clear dose-response correlation, highlighted in recent reviews,1,2,8 calls for further study.

Data on the clinical efficacy of low-dose nivolumab are rapidly accumulating. After the first 2 cases describing the efficacy of low-dose nivolumab (both in the post-transplant setting, to avoid graft-versus-host disease17 and immune thrombocytopenia3), several case series have shown clinical efficacy in Hodgkin lymphoma,6,18 as well as other solid organ malignancies.19,20 Lepik et al7 in a phase 2 trial used a fixed dose of nivolumab 40 mg in 30 patients with R/R Hodgkin lymphoma who were heavily pretreated, with an ORR of 70% and CR rate of 43%. In a retrospective analysis from our center21 comparing patients with R/R Hodgkin lymphoma receiving 3 mg/kg nivolumab with those receiving a flat dose of 40 mg, we found no difference in response rates, making the 40 mg dosing standard practice in our setting for patients with R/R Hodgkin lymphoma who were failing other salvage regimens and unable to afford therapy with approved doses.

Based on this real-world experience with low-dose nivolumab, we initiated a phase 2 trial in which patients with first relapse or progression of Hodgkin lymphoma received a short immune-modulatory regimen with low-dose nivolumab (NIV40) in combination with a low dose of lenalidomide (LEN10). The study protocol aimed to balance efficacy with cost, and rationalize dosing using flow cytometric characterization of the PD-1 receptors as a marker of drug adequacy and persistence.

The NIV40-LEN10 treatment regimen was well tolerated, and only 1 patient had a clinically evident autoimmune adverse reaction. There were no notable hematological or nonhematological toxicities. Though the trial did not meet its target CR rate of 80%, the ORR was 90% (18/20 patients). In a clinical setting, all 6 patients with a good PR would have been eligible for ASCT in view of low tumor burden; however, on trial, patients in PR were offered further salvage therapy to optimize response prior to ASCT for the best possible long-term outcomes.22 The relapse-free survival of patients who underwent ASCT was 93%, comparable with outcomes using full-dose nivolumab as a bridge to transplant, with other retrospective studies showing a similar disease-free survival of 87.5%23 and 93%.24 All patients undergoing ASCT had adequate stem cell mobilization without chemo-mobilization, suggesting that this regimen does not adversely impact stem cell reserve.

The currently practiced 14-day dosing frequency of standard-dose nivolumab (240 mg flat-dose or 3 mg/kg) and the 28-day dosing frequency (at 480 mg flat-dose) are based on model-based predictions25 as well as pharmacokinetic data from clinical trials.26 We were unable to demonstrate a correlation between drug half-life and outcome, and previous studies correlating drug clearance of PD-1 inhibitors with tumor dynamics have also shown conflicting results,27-29 with no clear link between plasma drug levels and response to treatment. Notably, similar to the data shown here, there was also no correlation between drug clearance and PD-1 RO by flow cytometry in previous reports,15,30 with RO persisting even at trough plasma levels.

Clinical trials in ICIs have used traditional pharmacokinetics to determine dosing frequency; however, dose adequacy and dosing frequency may be better evaluated through RO rather than plasma drug levels. Flow cytometric methods used for RO studies must be standardized and take into account the possible causes for false overestimation of RO, including steric hindrance from the therapeutic antibody, as well as possible receptor internalization.30

Here, we performed flow cytometry to assess baseline PD-1 expression and RO at the peak and trough levels after infusion of NIV40. While there was significant interpatient variation in baseline PD-1 expression, post-NIV40 infusion of PD-1 receptors on T cells showed near-complete RO in all patients, which persisted until the second scheduled dose of nivolumab despite a decrease in plasma drug levels, similar to previous studies.15,30 Because the planned treatment protocol mandated nivolumab infusions every 2 weeks, subsequent doses were given as per protocol; however, the complete RO at trough supports the extension of the duration between infusions. Previous studies have shown peak occupancy of >90%, with a trough 70% RO at 56 days after infusion, with no discernible difference at doses of 0.1 mg/kg and 10 mg/kg.15,30 By using flow cytometry to gage receptor availability, this will allow “top-up” infusions, rather than a standard infusion time point and dose, when PD-1 receptors are already completely saturated. Extended-duration infusions have been modeled in various malignancies,31 and trialed in prostatic carcinoma during the maintenance phases of therapy.32

From the data presented here, the PD-1 receptors on circulating T cells are completely saturated even at low doses of nivolumab, and drug persistence on the cell surface PD-1 receptor far exceeds the recommended pharmacokinetic-based dosing time points. This observation is consistent with previous reports describing the persistence of complete receptor saturation beyond the approved time-to-next infusion.15,30,33 Given the possible compartmental differences in immune activation status between intra-tumoral lymphocytes and circulating/nodal T cells, PD-1 receptor saturation in peripheral blood T cells may not fully reflect the status of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes.34

Through the efficacy and RO data shown here, we propose an alternative model of scheduling and dosing for nivolumab, based on PD-1 RO rather than plasma drug levels. In regions where flow cytometry is available, this will prove to be a useful tool to personalize nivolumab dosing and extend the duration between infusions, using PD-1 RO in individual cases to rationalize therapy. In regions with resource constraints where flow cytometry is not available, the duration of infusion could be extended, based on available data,13,26 to 4 to 6 weekly infusions, with resultant cost-savings that will significantly improve medication access.

Given these results demonstrating the efficacy of NIV40 in the relapsed setting, we have initiated a phase 3 randomized control trial with short-course NIV40+AVD (adriamycin, vinblastine, dacarbazine) in newly diagnosed advanced stage Hodgkin lymphoma, comparing outcomes with the standard ABVD regimen, using a risk-adapted strategy.35

Conclusion

This proof-of-concept phase 2 trial demonstrates that a short-course of immunomodulation with NIV40-LEN10 in R/R Hodgkin lymphoma is feasible, effective, and well tolerated. Prospective trials comparing NIV40-LEN10 with standard salvage protocols are required to validate these results. NIV-40 is sufficient for complete PD-1 RO with adequate clinical effect, challenging the need for the recommended 3 mg/kg dose. PD-1 RO is maintained beyond the recommended dosing time points, providing a rationale for increasing the interval between dosing and using PD-1 receptor saturation instead of plasma drug levels to guide drug dose and frequency. These measures will help reduce the costs associated with current regimens, and allow for more widespread, equitable, and rationalized use of PD-1 inhibitors.

Acknowledgment

This work was carried out with funding from an Internal Research Grant from the Christian Medical College, Vellore, India.

Authorship

Contribution: A.K. and V.M. designed the research, analyzed data, and wrote the paper; U.K. was responsible for monitoring trial oversight; A.K.A. and P.D.V. analyzed the flow cytometry data; A.A.P., S.M., and P.B. conducted and analyzed the pharmacokinetic studies; K.M.L. analyzed the data; and F.N.A., S.S., S.L., A.A., and B.G. recruited patients and were involved in trial conduct.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Anu Korula, Department of Haematology, Christian Medical College Vellore, Ranipet Campus, Kilminnal Village, Vellore 632517, India; email: anukorula@cmcvellore.ac.in.

References

Author notes

All source data are available from the corresponding author, Anu Korula (anukorula@cmcvellore.ac.in), on request.

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.