Key Points

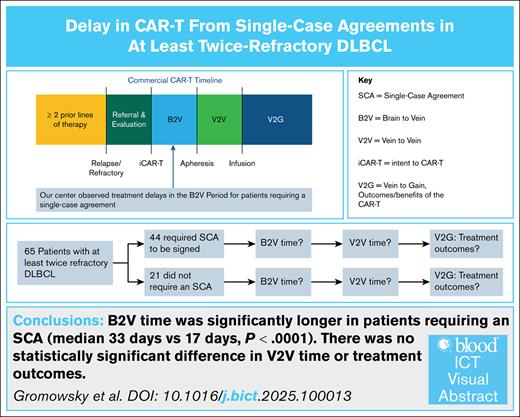

Patients who required an SCA experienced a significantly longer B2V time than those who did not.

There were no statistically significant differences in the treatment outcomes between those who required an SCA and those who did not.

Visual Abstract

Chimeric antigen receptor T cell (CAR-T) is an effective treatment for relapsed/refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL). Delays before apheresis, particularly because of the need for a single-case agreement (SCA) between treatment centers and insurers, can impact timely access to care. We performed a single-center, retrospective study of 65 patients with at least twice treated DLBCL who intended to receive commercial CAR-T therapy between 2018-2022. Patients were stratified by SCA requirements. The preinfusion timeline was divided into the brain-to-vein (B2V; intent to apheresis) and vein-to-vein (V2V; apheresis to infusion) periods. Outcomes that were evaluated include complete response (CR), progression-free survival (PFS), overall survival (OS), and cellular therapy intent quotient (CTIQ, defined as the fraction of patients infused among those who intended to receive CAR-T therapy). A total of 44 patients (68%) required an SCA. The median B2V time was significantly longer in the SCA group (33 vs 17 days; P < .0001). The V2V times were similar. No significant differences were observed in CR (46% vs 57%; P = .42), PFS (7.33 vs 16.56 months; P = .22), OS (15.34 vs 44.62 months; P = .10), or CTIQ (88.6% vs 100%; P = .17) for the SCA and non-SCA groups, respectively. SCAs contribute to delays in CAR-T initiation without significantly affecting the outcomes. Streamlining preapheresis processes may help to improve timely access to CAR-T therapy.

Introduction

Chimeric antigen receptor T-cell (CAR-T) therapy has become an essential component of the treatment armamentarium for diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL). The most commonly used CAR-T constructs are directed at CD19 and have shown efficacy in multiple clinical trials, and 2 CAR-T products are now approved as second-line therapy for relapsed/refractory DLBCL.1 However, real-world workflows for commercial CAR-T products at authorized treatment centers (ATCs) often include delays that are not present in trials, including referral processing, patient evaluation, purchase authorization, and, frequently, the negotiation of a single-case agreement (SCA).

To better quantify preinfusion delays, time may be divided into 2 distinct parts, namely the brain-to-vein (B2V) and vein-to-vein (V2V) periods. The B2V interval covers the time from when a patient and care team decide on CAR-T therapy to the date of apheresis. The V2V period spans from cell collection to infusion.

Although complications like infection or hospitalization can cause delays in both periods, the V2V delays are primarily related to product-specific manufacturing timelines that are established during clinical trials.2 B2V delays, however, may be influenced by several factors, including social determinants and insurance processes. We observed at our ATC that requiring an SCA may be a potential contributor to a prolonged B2V time.2,3

An SCA is a contract between the company and the ATC that enables patients to receive therapy using their in-network benefits. Larger-volume centers may not require a signed SCA for certain insurance companies; however, many medium-sized centers require a signed SCA because of the volume of CAR-T infusions and the cost of the commercial product. Patients with specific public insurance may not require an SCA, because CAR-T therapy is typically covered in-network by Medicare and Medicaid.

Because of the delay in treatment observed among patients who require an SCA, we hypothesized that there would be a difference in the B2V time between patients who require an SCA and those who do not require one. In addition, we hypothesized that patients who do not require an SCA would experience significantly improved treatment outcomes, including improvements in the percentage of patients who achieve a complete response (CR) and improved progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS), because it has been shown in other malignancies that delays in treatment can be associated with worse outcomes.4

Methods

Eligibility criteria

We conducted a single-center, retrospective analysis of consecutively evaluated patients with DLBCL who had received ≥2 previous lines of therapy and who intended to undergo commercial CAR-T therapy at the University of Nebraska Medical Center between 2018 and 2022 with a single CAR-T product. The study was limited to third-line CAR-T therapy and beyond, as well as a single product to provide uniformity in the patient cohort.1 This was a retrospective quality assurance study that did not require institutional review board approval. This project was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

A record of all patients who were evaluated for commercial CAR-T therapy at our center was reviewed. For patients who were evaluated but who did not receive CAR-T infusion or apheresis, the patient encounter was analyzed to determine whether the patient and provider intended to proceed with CAR-T therapy or whether the patient did not intend to pursue it further at our treatment center. Patients who were evaluated but who did not further pursue CAR-T therapy were excluded from the study. In addition, patients who participated in a clinical trial or who received a nonconforming commercial CAR-T product were excluded.

Patients were grouped based on whether they required an SCA to be signed between their insurance company and the ATC before treatment.

Baseline characteristics

The patient and disease characteristics were collected at the time of intent to CAR-T and included sex, race, performance status, lactate dehydrogenase, tumor burden, disease status, and insurance type. For all patients for whom a firm intention to pursue CAR-T therapy had been documented in the physician’s plan following an encounter, this date was recorded as the intent to CAR-T (iCAR-T) date. Some patients did not have a note clearly stating the intent to undergo CAR-T treatment in the physician’s documented plan. For these patients, the first documented record in the electronic health record stating a definitive intent to receive CAR-T, such as communication with the patient’s insurance company, was recorded as the iCAR-T date. We believe that both types of documentation are an accurate estimate of true iCAR-T, because such communication was often sent on the same day that the intent was determined for patients who had a documented physician plan.

End points

For the survivorship analysis, the iCAR-T date was used as the starting point to capture all patients who intended to receive CAR-T for our primary survivorship end points. In addition, we used the date of infusion of those who were infused as a secondary analysis.

The primary end points for this study were the best response of CR, PFS, and OS. The PFS and OS were determined using the iCAR-T date and not the date of infusion. In addition, the cellular therapy intent quotient (CTIQ), defined as the number of patients infused with a CAR-T product vs those who intended to undergo CAR-T treatment, was determined for each cohort. The CTIQ was developed for this analysis to capture patients lost before the initiation of therapy, and it is a valuable method for comparing patients lost who have not been included in most studies.

Secondary end points included the number of days between the iCAR-T date and the signing of an SCA for the patients who needed one, the B2V time (the number of days between iCAR-T and apheresis would be compared between the 2 cohorts), and the V2V time (the number of days between apheresis and infusion). In addition, the best response of CR, PFS, and OS were determined using the date of infusion.

Statistical analysis

PC SAS, version 9.4, was used for all summaries and analyses. The statistical level of significance was 0.05 for all analyses. The OS and PFS from infusion (OS and PFS infusion) and iCAR-T (OS and PFS CAR-T) were analyzed. Log-rank tests were used to compare the Kaplan-Meier curves. The median survival with 95% confidence intervals are presented.

Categorical variables were summarized using frequencies and percentages and analyzed using a χ2 test, except when the expected case counts fell below 5; in that case, a Fisher exact test was used instead. Continuous data were first tested for normality using the Shapiro-Wilks test. All continuous variables failed the test of normality except for age. For those who failed the test of normality, a nonparametric Mann-Whitney U test was used to analyze the data, and the median, quartiles, and minimum and maximum values are presented. Age was analyzed using an equal variances t test, and the mean and standard deviation are presented.

Results

Between 2018 and 2022, 158 patients were evaluated at our center for consideration to receive commercial CAR-T therapy. Of those, 77 showed intent to pursue commercial CAR-T therapy. Of the remaining 81 patients, 19 participated in a clinical trial. In contrast, 62 did not further pursue CAR-T therapy at our center for reasons that included pursuing CAR-T therapy at a different treatment center, declining CAR-T treatment, or being deemed medically or socially ineligible for CAR-T. Of the 77 patients who intended to move forward with commercial CAR-T therapy, 65 were determined to have the intent to pursue CAR-T therapy using a single CAR-T product analyzed in this study; the other 12 pursued therapy with a different commercial CAR-T product and were excluded from the analysis.

All patients analyzed received ≥2 lines of therapy before pursuing CAR-T therapy. A total of 44 patients (68%) required an SCA, whereas 21 (32%) did not. Patients who required an SCA either had private insurance or Medicare with a managed plan. There was no difference between cohorts based on sex, race, performance status, lactate dehydrogenase, previous lines of therapy, or tumor burden. The SCA cohort had a significantly greater number of patients with refractory disease to their last therapy (55% vs 29%; P = .0495). In addition, as expected, the non-SCA cohort was significantly older than the SCA cohort with mean ages of 69 and 55 years at the time of iCAR-T (P < .0001). The CTIQ for all patients was 92.3% (60/65). The CTIQ was 88.6% (39/44) for the SCA group and 100% (21/21) for the non-SCA group (P = .17). Table 1 summarizes the baseline characteristics of the patient population in each cohort. Only 1 patient in the SCA cohort underwent apheresis but the product was not infused.

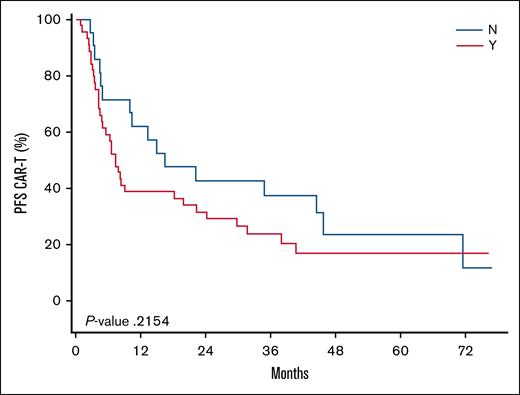

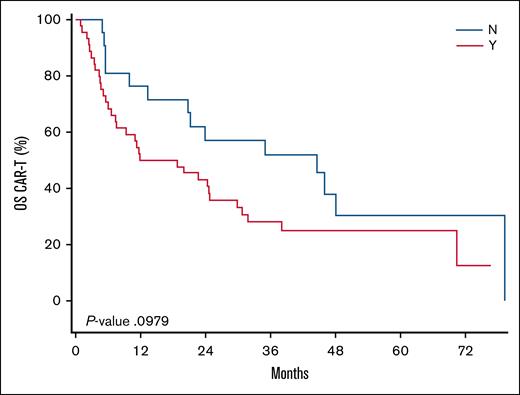

We found that the median time from iCAR-T to the signing of an SCA was 24 days (range, 7-78). The median B2V time for the SCA cohort was 33 days (range, 8-67), and the median B2V time for the non-SCA cohort was 17 days (range, 7-78). This difference was found to be statistically significant (P = .0002). The median V2V times for the SCA and non-SCA groups was 27 days for both cohorts. No significant differences were observed in CR (46% SCA vs 57% non-SCA; P = .42). Following iCAR-T, the median PFS was 7.33 months and 16.56 months (P = .22) and the median OS was 15.34 and 44.62 months (P = .10) for the SCA and non-SCA groups, respectively. The Kaplan-Meier curves for the PFS and OS of these cohorts following iCAR-T can be visualized in Figure 1 and Figure 2, respectively. Following infusion, the median PFS was 6.47 months and 15.11 months (P = .35) and the median OS was 20.44 months and 42.45 months (P = .20) for the SCA and non-SCA groups, respectively. The median follow-up was 51.9 months following iCAR-T.

Kaplan-Meier curve comparing the PFS among patients who did not require (N) vs those who required (Y) an SCA. Time 0 is the date of iCAR-T. The median PFS was 7.33 months for the SCA and 16.56 months for the non-SCA cohorts (P = .22).

Kaplan-Meier curve comparing the PFS among patients who did not require (N) vs those who required (Y) an SCA. Time 0 is the date of iCAR-T. The median PFS was 7.33 months for the SCA and 16.56 months for the non-SCA cohorts (P = .22).

Kaplan-Meier curve comparing the OS among patients who did not require (N) vs those who required (Y) an SCA. Time 0 is the date of iCAR-T. The median OS was 15.34 months vs 44.62 months for the non-SCA cohort (P = .10).

Kaplan-Meier curve comparing the OS among patients who did not require (N) vs those who required (Y) an SCA. Time 0 is the date of iCAR-T. The median OS was 15.34 months vs 44.62 months for the non-SCA cohort (P = .10).

Discussion

Although the outcome differences were not statistically significant, it remains possible that a study with a larger sample size could demonstrate that this magnitude of difference is statistically significant4; it also remains possible that a median difference of 16 days is not large enough to affect outcomes no matter the sample size. The larger portion of the SCA cohort with refractory disease could have driven the differences in outcomes.5-7 The older age of the non-SCA cohort is expected, and some studies have shown that older age has not negatively affected outcomes, such as OS.8 These findings are similar to those at other institutions that have also reported pretreatment delays among patients who required an SCA without negatively affecting outcomes, although our study excluded patients who were initially considered for CAR-T but who were found to be ineligible. In addition, the iCAR-T date was used as opposed to the date of evaluation for CAR-T eligibility.9

This study revealed a significant B2V delay associated with SCAs that are often required for commercial CAR-T therapy. Although data on the B2V for patients enrolled in clinical trials were not collected, the observed delays align with a common trend at our treatment center, namely patients to be treated with commercial CAR-T therapy often face longer treatment timelines than clinical trial participants. Identifying this delay has enabled us to work to streamline the negotiation of SCAs, prioritize early apheresis (when possible, before SCA signature), and aggressively consider preapheresis bridging in patients who require an SCA to be negotiated. Although some delays may not be captured by the B2V period, such as delays to assessment at our treatment center for patients with external referrals, defining and analyzing the B2V period provides a clearer view of real-world delays not captured in prospective trials and highlights the need to reduce pretreatment barriers in CAR-T access.

Authorship

Contribution: M.J.G. performed the data collection, assisted with data interpretation, and drafted the manuscript; C.R.D., J.O.A., R.G.B., and J.M.V. provided insight and helped with data interpretation; R.E. assisted with data organization and interpretation; V.K.S. performed the statistical analysis and designed the figures and tables; and M.A.L. conceived the presented idea and supervised the findings of this work.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Matthew J. Gromowsky, University of Nebraska Medical Center, 42nd and Emile, Omaha, NE 68198; email: mgromowsky@unmc.edu.

References

Author notes

The data that support the findings of this study are not publicly available because of privacy concerns.

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.