Key Points

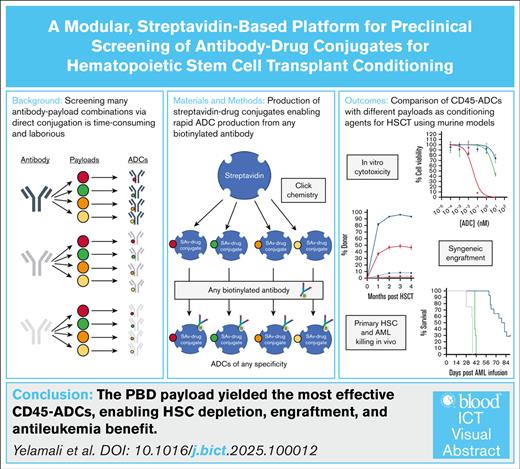

CD45-ADCs with various payloads were compared using a modular SAv-drug conjugate platform, which enabled rapid, efficient ADC screening.

The PBD dimer SGD-1882 prevailed for HSCT conditioning, enabling donor HSC engraftment and providing significant antileukemia benefit.

Visual Abstract

Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) conditioning using antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs) is a promising approach to preparing patients for transplant, potentially avoiding the severe toxicities of conventional chemotherapy- and irradiation-based conditioning regimens. The toxic payload determines the efficacy and potential toxicities of an ADC, but comparison of different payloads in conjugates designed for HSCT conditioning has, to our knowledge, not been reported. Such comparisons would be greatly facilitated by methods enabling efficient screening of many combinations of antibody and payload. Herein, we used copper-free azide-alkyne cycloaddition to conjugate 4 different small-molecule payloads to a streptavidin (SAv) backbone, yielding SAv-drug conjugates that can be combined with any biotinylated antibody to rapidly and cost-effectively produce an ADC. We vetted this system by evaluating CD45-targeted ADCs, finding pyrrolobenzodiazepine (PBD) dimers to be the most effective payload of those we tested for targeting mouse and human HSCs and acute myeloid leukemia (AML) cells. Single-dose murine CD45-PBD enabled near-complete conversion to donor hematopoiesis in syngeneic HSCT models as well as in autologous transplantation using gene-edited HSCs. Finally, human CD45-PBD targeted human HSCs in vivo and provided significant antileukemia benefit in a patient-derived AML xenograft model. Notably, our SAv-drug conjugates were produced using routine molecular biology techniques and readily available supplies without requiring complex instrumentation, making production and screening of ADCs for myriad targeting applications accessible to virtually any laboratory.

Introduction

Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) is a potentially curative therapy for a variety of malignant and nonmalignant hematologic diseases. In preparation for HSCT, patients undergo treatment, or “conditioning,” with chemotherapy and/or irradiation to ablate their HSC compartment to enable engraftment of HSCs from their donor.1 For malignancies, conditioning regimens also deplete malignant cells that were not eliminated by the patient’s previous therapies, with higher-intensity regimens providing greater antitumor benefit and protection against relapse.2 However, the risks of toxicities from conventional conditioning agents impose a significant barrier to the curative potential of transplantation.3,4

There is considerable interest in immunotherapeutic conditioning approaches that deplete the HSC niche while avoiding the toxicities of chemotherapy- and irradiation-based conditioning.5,6 Antibody-drug conjugate (ADC)–based regimens targeting the phosphatase CD45 or the tyrosine kinase CD117 (c-kit) have safely enabled both syngeneic7-9 and allogeneic10-13 HSCT (allo-HSCT) in preclinical models. However, clinical translation of CD45- and CD117-targeted conditioning agents has faced significant setbacks; for instance, although allo-HSCT after conditioning with the CD45-targeted radioimmunoconjugate 131I-apamistamab led to higher durable complete remission rates compared with conventional conditioning,14 it was denied US Food and Drug Administration approval pending demonstration of an overall survival benefit. Furthermore, a fatal cardiopulmonary adverse event halted a trial of an α-amanitin–based CD117-ADC.15 These results highlight the enduring challenge of developing and translating ADCs that successfully balance therapeutic efficacy with potential for toxicities.

A central determinant of ADC efficacy is the ability to be specifically internalized by target cells and deliver its cytotoxic drug payload.16 As such, the choice of payload linked to the antibody is of paramount importance. For preclinical modeling in the mouse, we, and others, have used the ribosome inactivating protein saporin as an ADC payload.7,8,12,16-18 Saporin is available in a streptavidin (SAv)-conjugated format, enabling rapid production of ADCs from any biotinylated antibody.19 However, our HSCT studies with CD45- and CD117-saporin showed that although these conjugates could induce stable multilineage donor chimerism, they provided minimal antitumor benefit in the murine A20 lymphoma model.12 We improved upon this by developing CD45- and CD117-ADCs with a pyrrolobenzodiazepine (PBD) payload, which enabled conversion to full donor chimerism and provided durable protection against an aggressive murine acute myeloid leukemia (AML) model.20 Although PBD has been successfully used in the CD19-targeted ADC loncastuximab tesirine,21 toxicities from the highly potent PBD payload remain a potential clinical concern as evidenced by discontinuation of the phase 3 trial investigating the CD33-targeted ADC vadastuximab talirine as frontline therapy for AML.22

Saporin and PBD are just 2 of many potential ADC payloads, most of which have not been evaluated in the context of HSCT conditioning. Investigation of alternative payloads may enable development of ADCs that more optimally balance efficacy with toxicities. Moreover, screening of novel antibodies targeting CD45, CD117, or other receptors may reveal alternative clones with superior efficacy as HSCT-conditioning ADCs. However, direct conjugation of drug payloads to candidate antibodies can become time consuming, laborious, and expensive, particularly when screening many antibody-payload combinations is desirable.23 A platform capable of rapidly and cost-effectively linking antibodies to drug payloads would greatly facilitate in vitro and in vivo evaluation of ADC in preclinical and translational studies.

To meet this need, we used copper-free azide-alkyne cycloaddition (“Click” chemistry) to construct a novel panel of SAv-drug conjugates,24 enabling indirect conjugation of any biotinylated antibody to one of several different toxic payloads (Figure 1A). Importantly, our SAv-drug conjugates make use of readily available reagents and supplies and do not require complex instrumentation for production or purification, making production of ADCs in sufficient quality and quantity for in vitro and in vivo studies accessible to any laboratory equipped for routine molecular biology. Herein, we use fully murine and humanized mouse model systems to demonstrate the utility of our platform for identifying effective antibodies and payloads for use as HSCT conditioning agents.

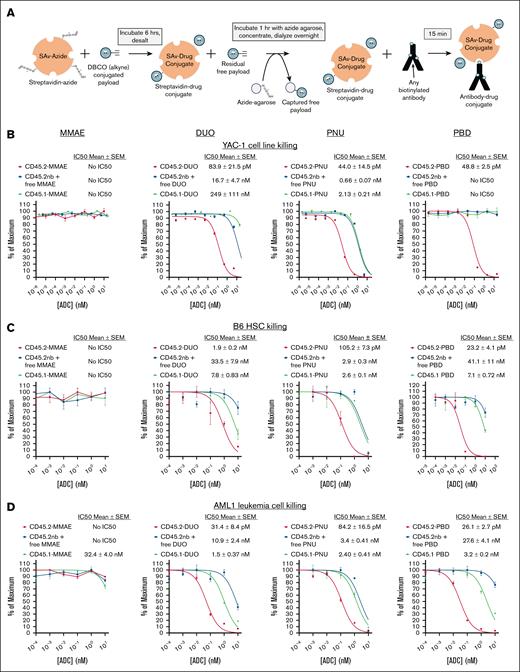

SAv-drug conjugates yield CD45.2-ADCs that are cytotoxic against murine cell lines, primary HSCs, and primary AML cells. (A) Schema for production of SAv-drug conjugates and conjugation to biotinylated antibodies to produce ADCs. (B-D) Cytotoxicity assays of anti-CD45.2-ADC (biotinylated antibody plus SAv-drug conjugate), nb anti-CD45.2 plus free SAv-drug conjugate, or CD45.1-ADC (biotinylated isotype control plus SAv-drug conjugate) against (B) YAC-1 cells, (C) HSCs from B6 mice, and (D) AML1 primary leukemia cells (Dnmt3aR878H/+, FLT3-ITD+). Data points represent mean ± SEM of duplicate colony forming unit (CFU) plates (C) or triplicate wells (B,D) taken from 1 representative of at least 3 independent experiments. DBCO, dibenzocyclooctyne; IC50, 50% inhibitory concentration; SEM, standard error of the mean. nb, nonbiotinylated.

SAv-drug conjugates yield CD45.2-ADCs that are cytotoxic against murine cell lines, primary HSCs, and primary AML cells. (A) Schema for production of SAv-drug conjugates and conjugation to biotinylated antibodies to produce ADCs. (B-D) Cytotoxicity assays of anti-CD45.2-ADC (biotinylated antibody plus SAv-drug conjugate), nb anti-CD45.2 plus free SAv-drug conjugate, or CD45.1-ADC (biotinylated isotype control plus SAv-drug conjugate) against (B) YAC-1 cells, (C) HSCs from B6 mice, and (D) AML1 primary leukemia cells (Dnmt3aR878H/+, FLT3-ITD+). Data points represent mean ± SEM of duplicate colony forming unit (CFU) plates (C) or triplicate wells (B,D) taken from 1 representative of at least 3 independent experiments. DBCO, dibenzocyclooctyne; IC50, 50% inhibitory concentration; SEM, standard error of the mean. nb, nonbiotinylated.

Materials and methods

Mice

The following mouse strains were purchased from The Jackson Laboratories or bred in-house: C57BL6/J (000664), C57BL/6-Tg(UBC–green fluorescent protein [GFP])30Scha/J (B6-GFP; 004353); and NSG-SGM3 (NSGS; 013062).

Cell culture

The YAC-1, Jurkat, and MOLM13 cell lines were obtained from American Type Culture Collection. Murine spleens, bone marrow, and peripheral blood were collected as previously described.12,25 Murine primary AML1 cells (Dnmt3aR878H/+/FLT3-internal tandem duplication [ITD]+, GFP+) were generated as previously described.26 Deidentified human umbilical cord blood specimens were obtained from the Cleveland Cord Blood Center; cord blood units were processed by Ficoll centrifugation to yield mononuclear cell fractions for use for in vitro cytotoxicity assays or underwent CD34+ purification using the EasySep Human Cord Blood CD34+ Selection kit II (STEMCELL Technologies) for generation of humanized mice. Deidentified primary AML specimens were obtained from our institutional biobank and expanded via passage into NSGS mice.

In vitro ADC cytotoxicity against cell lines was assessed using a XTT viability assay (Cell Signaling Technology), as previously described.12 ADC cytotoxicity against mouse and human HSCs was assessed using colony forming unit assays.12 Cytotoxicity against mouse and human AML cells was assessed by culturing cells with concentration series of ADC in complete mouse or human methylcellulose media, then enumerating total viable cells by flow cytometry.

SAv-drug conjugates

SAv-azide (Protein Mods Inc) at 2 to 5 mg/mL in phosphate-buffered saline was prepared for conjugation by adding dimethyl sulfoxide to 20% final concentration as a cosolvent. Dibenzocyclooctyne-linked ADC payloads with cathepsin-cleavable linkers (Levena Biopharma; supplemental Figure 1) were dissolved at 10 mM in dimethyl sulfoxide in preparation for conjugation. SAv-azide and dibenzocyclooctyne-linked payloads were conjugated via a Click chemistry reaction (Figure 1A). Free payload was removed with multiple sequential cleanup steps including desalting with Zeba 7-kDa spin columns (ThermoFisher), capture of free payload with azide agarose (Vector Laboratories), and dialysis using Slide-A-Lyzer MINI 10-kDa devices (ThermoFisher). After dialysis, SAv-drug conjugates were quantified by bicinchoninic acid assay and filter sterilized using a 0.22-μm polyethersulfone syringe filter. To produce ADCs, SAv-drug conjugates were mixed in a 1:1 molar ratio with biotinylated antibodies and incubated for 15 minutes at 20°C, then diluted to the desired final concentration.

In vivo murine HSC depletion and HSCT models

For terminal HSC depletion studies, B6 mice were infused with 60 μg ADC via retroorbital injection (50 μg for directly conjugated ADCs) then euthanized 7 days later to assess complete blood counts (CBCs) and depletion of HSCs and mature immune cells in the spleen and bone marrow. For syngeneic HSCT studies, B6 recipients were treated with 60 μg CD45.2-PBD or CD45.2–nemorubicin metabolite PNU-159682 (PNU), then infused 6 days later with 10 × 106 B6-GFP whole bone marrow cells; for engraftment of autologous gene-edited HSCs, 1 × 105 GFP-edited HSCs were infused into ADC-conditioned B6-GFP mice.

Humanized mouse models

For human HSCs depletion studies, 1 × 105 purified cord blood–derived CD34+ cells were infused into sublethally irradiated (250 cGy) NSGS mice (day 0), then recipients received 60 μg CD45-ADC or isotype control ADC 7 days later. At the time of treatment, there were no significant differences between groups in human peripheral blood chimerism. Mice were subsequently analyzed at 2 and 4 weeks after cell infusion for emergence of human-derived hematopoiesis in the peripheral blood, then euthanized at 4 weeks after cell infusion to assess absolute human CD34+ counts in the bone marrow. To assess the antileukemia function of human CD45-ADCs, 3 × 106 patient-derived AML cells were infused into sublethally irradiated NSGS mice (day 0), then recipients received 60 μg ADC 7 days later and were followed up longitudinally for survival, CBCs, and leukemia burden. At the time of ADC treatment, no mice had detectable AML involvement in the peripheral blood.

Animal experiments complied with a research protocol approved by the Washington University Institutional animal care and use committee. Adult AML specimens were banked with institutional review board approval from the Washington University Human research protection office.

Results

Evaluation of CD45.2-ADCs produced from SAv-drug conjugates

We selected 4 drug payloads for initial development of our SAv-drug conjugate platform (supplemental Figure 1): the tubulin inhibitor monomethyl auristatin E (MMAE),27 the DNA alkylating agent duocarmycin SA (DUO),28 PNU,29 and the PBD dimer SGD-1882 (PBD).30 Commercially prepared SAv-azide provided a source of Click reaction–ready protein with 2 to 4 confirmed azide groups per SAv tetramer. Mass spectrometry confirmed successful SAv-payload conjugation, with drug-SAv ratios ranging from 0.55 to 2.55 (supplemental Figure 2). Sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis analysis with biotin-SAv supershift assays confirmed the protein purity of each SAv-drug conjugate and that their ability to bind biotinylated ligands was unaffected by the conjugation (supplemental Figure 3).

We first performed in vitro cytotoxicity testing of ADCs made with our SAv-drug conjugates linked to anti-CD45.2 clone 104,8,12 using the YAC-1 cell line, whole bone marrow cells from B6 mice, and AML1 primary murine leukemia cells26 as targets. CD45.2-ADCs containing the DUO, PNU, and PBD payloads were cytotoxic against all target cell types (Figure 1B-D); notably, CD45.2-MMAE showed no cytotoxicity toward any cell type, suggesting MMAE would be ineffective for HSCT conditioning in mice. Although CD45-DUO was highly cytotoxic toward AML1 cells, it showed only modest potency against HSCs, suggesting it would also be suboptimal for HSCT conditioning. CD45.2-PNU and CD45.2-PBD were the most potent at depleting B6 HSCs, with CD45.2-PBD having a wider therapeutic window when compared with our 2 negative control conditions (nonbiotinylated antibody plus free SAv-drug conjugate or CD45.1-PBD). Thus, in vitro screening of CD45-ADCs using our SAv-drug conjugate platform vetted the PNU and PBD payloads as potentially effective in HSCT conditioning ADCs.

During our initial cytotoxicity studies, we undertook several quality control studies to evaluate the robustness of the SAv-drug conjugate system. We focused on SAv-PBD for these experiments because this conjugate yielded the most effective CD45.2-targeted ADCs. First, using liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry, we identified minimal free PBD payload signal in 2 independent SAv-PBD preparations above the background of unconjugated SAv-azide (supplemental Figure 4). Next, we evaluated whether the cytotoxicity of CD45.2 PBD produced with SAv-PBD was comparable with that of CD45.2-PBD produced via direct conjugation methods. Indeed, when compared with equimolar doses of directly conjugated ADCs made using standard maleimide-thiol coupling or with a Click chemistry–based payload conjugation, indirectly conjugated CD45.2-PBD made with SAv-PBD showed comparable in vitro and in vivo cytotoxicity (supplemental Figure 5). Finally, we compared the activity of CD45.2-PBD conjugates made using 4 separate batches of SAv-PBD, finding minimal lot-to-lot variability in yields, specific cytotoxicity, or nonspecific toxicity; notably, minimal loss in activity was observed after 3 freeze-thaw cycles or prolonged storage at 4°C (supplemental Figure 6).

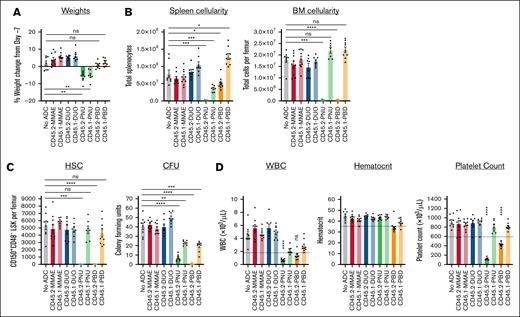

CD45.2-ADCs as conditioning agents for murine HSCT

To identify the most effective candidates as conditioning agents for HSCT, we tested the ability of our CD45.2-ADCs to deplete HSCs in vivo and evaluated their impact on CBCs and major peripheral leukocyte populations. ADC doses of 60 μg were used because this is the molar equivalent of the 75 μg dose of the CD45.2-saporin ADCs that we have used previously.12 Acute exposure to the ADCs was generally well tolerated, but markedly reduced spleen cellularity and significant weight loss were observed with both CD45.2- and CD45.1-PNU, indicating nonspecific toxicity (Figure 2A-B). As expected from our in vitro cytotoxicity studies, CD45.2-PNU and CD45.2-PBD effectively depleted phenotypic HSCs (CD150+CD48− Lineage-Sca1+c-Kit+ [LSK]) and colony forming activity (Figure 2C; supplemental Figure 7). Marrow ablation by the CD45.2-ADCs was largely due to specific toxicity, because CD45.1-PNU and CD45.1-PBD conjugates did not significantly deplete HSCs or HSPCs and only partially reduced colony formation. By contrast, CD45.2-DUO, CD45.2-MMAE, and their respective CD45.1 control conjugates did not markedly affect cell populations in the bone marrow, spleen, or peripheral blood. Given these results, CD45-PBD and CD45-PNU proceeded to testing as conditioning for HSCT.

CD45.2-PNU and CD45.2-PBD deplete B6 HSCs in vivo, with greater nonspecific toxicities for the PNU payload. B6 mice were either untreated (no ADC) or infused with 60 μg ADC produced by combining the indicated biotinylated antibodies with SAv-drug conjugates (on day −7). Mice were then euthanized and analyzed 7 days later (day 0). (A) Weight change on day 0 compared with immediately before ADC treatment on day −7. (B) Total cellularity of the spleen and bone marrow. (C) Counts of CD48−CD150+ Lin–Sca1+c-Kit+ cells in the bone marrow (SLAM-LSK population; HSC), and total CFUs from the bone marrow of ADC-treated mice assessed after an 8-day incubation in complete mouse methylcellulose. (D) CBCs; dotted lines indicate the lower reference limit for each assay. For all panels, each data point represents a single mouse, and bars represent mean ± SEM from mice accumulated over 3 independent experiments. Statistics: 1-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Dunnett’s correction for multiple comparisons (normally distributed data sets) or Kruskal-Wallis test with Dunn’s correction for multiple comparisons (nonnormally distributed data sets). ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001. ns, not significant; WBC, white blood cell count.

CD45.2-PNU and CD45.2-PBD deplete B6 HSCs in vivo, with greater nonspecific toxicities for the PNU payload. B6 mice were either untreated (no ADC) or infused with 60 μg ADC produced by combining the indicated biotinylated antibodies with SAv-drug conjugates (on day −7). Mice were then euthanized and analyzed 7 days later (day 0). (A) Weight change on day 0 compared with immediately before ADC treatment on day −7. (B) Total cellularity of the spleen and bone marrow. (C) Counts of CD48−CD150+ Lin–Sca1+c-Kit+ cells in the bone marrow (SLAM-LSK population; HSC), and total CFUs from the bone marrow of ADC-treated mice assessed after an 8-day incubation in complete mouse methylcellulose. (D) CBCs; dotted lines indicate the lower reference limit for each assay. For all panels, each data point represents a single mouse, and bars represent mean ± SEM from mice accumulated over 3 independent experiments. Statistics: 1-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Dunnett’s correction for multiple comparisons (normally distributed data sets) or Kruskal-Wallis test with Dunn’s correction for multiple comparisons (nonnormally distributed data sets). ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001. ns, not significant; WBC, white blood cell count.

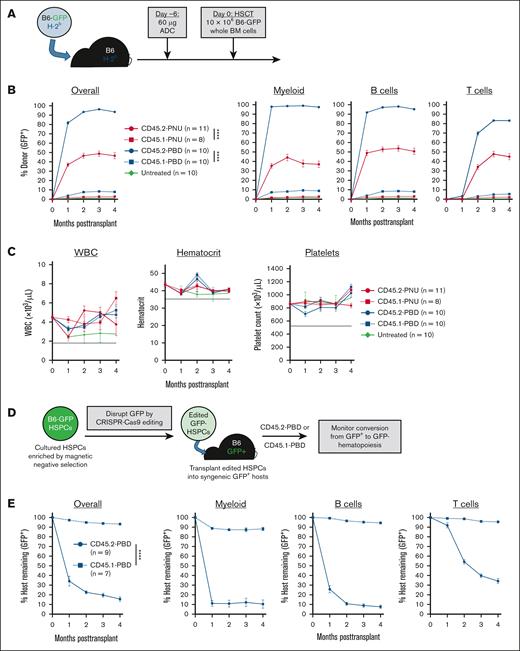

In a syngeneic HSCT model (B6-GFP→B6), CD45.2-PBD surpassed CD45.2-PNU in efficacy, enabling near complete conversion to donor hematopoiesis among myeloid and B cells, and high-level mixed chimerism among T cells (Figure 3B). Surprisingly, despite depleting phenotypic HSCs as effectively as CD45.2-PBD (Figure 2C), CD45.2-PNU enabled overall donor chimerism of only ∼50%. Considering that CD45.2-PNU’s poorer performance may be due to pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic differences, we conducted in vivo ADC persistence assays using a fluor-conjugated anti-SAv antibody to detect circulating and cell-bound ADCs made with a SAv-drug conjugate. These experiments showed that although free and cell-bound CD45.2-PNU in the peripheral blood diminished somewhat more quickly than CD45.2-PBD, both ADCs bioaccumulated in the lymphoid organs with comparable labeling of splenic leukocytes and bone marrow LSK cells (supplemental Figure 8).

CD45.2-PBD enables syngeneic HSCT and engraftment of autologous gene-edited HSCs with near-complete donor engraftment. (A) Schema for syngeneic HSCT of GFP-labeled B6 whole BM into B6 mice, using CD45.2-ADCs made with SAv-drug conjugates for conditioning. (B-C) Longitudinal peripheral blood donor chimerism overall and by lineage (B) and CBCs (C) in recipients conditioned with CD45.2-PNU, CD45.2-PBD, or their respective CD45.1-bound (isotype control) conjugates. Dotted lines in (C) are the lower reference limits for each CBC assay. (D) Schema for CRISPR-mediated disruption of GFP from B6-GFP HSPCs and transplantation of the edited HSPCs into B6-GFP mice. (E) Longitudinal peripheral blood donor chimerism overall and by lineage in CD45.2- or CD45.1-PBD conditioned B6-GFP mice receiving GFP-deleted HSPCs. For the populations of edited cells infused into these recipients, the average frequency of CD48−CD150+LSK cells that were GFP+ was 2.2% and 4.0% for CD45.2-PBD– and CD45.1-PBD–conditioned mice, respectively. Data points indicate mean ± SEM from mice accumulated over 2 independent experiments. Statistics: 2-way repeated-measures ANOVA (B,E). ∗∗∗∗P < .0001. BM, bone marrow; Cas9, CRISPR-associated protein 9; WBC, white blood cells.

CD45.2-PBD enables syngeneic HSCT and engraftment of autologous gene-edited HSCs with near-complete donor engraftment. (A) Schema for syngeneic HSCT of GFP-labeled B6 whole BM into B6 mice, using CD45.2-ADCs made with SAv-drug conjugates for conditioning. (B-C) Longitudinal peripheral blood donor chimerism overall and by lineage (B) and CBCs (C) in recipients conditioned with CD45.2-PNU, CD45.2-PBD, or their respective CD45.1-bound (isotype control) conjugates. Dotted lines in (C) are the lower reference limits for each CBC assay. (D) Schema for CRISPR-mediated disruption of GFP from B6-GFP HSPCs and transplantation of the edited HSPCs into B6-GFP mice. (E) Longitudinal peripheral blood donor chimerism overall and by lineage in CD45.2- or CD45.1-PBD conditioned B6-GFP mice receiving GFP-deleted HSPCs. For the populations of edited cells infused into these recipients, the average frequency of CD48−CD150+LSK cells that were GFP+ was 2.2% and 4.0% for CD45.2-PBD– and CD45.1-PBD–conditioned mice, respectively. Data points indicate mean ± SEM from mice accumulated over 2 independent experiments. Statistics: 2-way repeated-measures ANOVA (B,E). ∗∗∗∗P < .0001. BM, bone marrow; Cas9, CRISPR-associated protein 9; WBC, white blood cells.

For both CD45.2-PBD and CD45.2-PNU, post-HSCT CBCs were stably maintained within the reference range throughout the experiments (Figure 3C). Moreover, the donor chimerism in the peripheral blood was consistent with that observed among mature splenic leukocytes and bone marrow HSPC subsets (supplemental Figure 9). Finally, serial transplantation of bone marrow isolated from primary CD45.2-PNU or CD45.2-PBD conditioned recipients confirmed that these primary recipients had engrafted bona fide, serially repopulating HSCs (supplemental Figure 10). Taken together, our results show PBD to be the most effective payload of those we tested for CD45.2-ADC–based HSCT conditioning in the mouse, being both well tolerated and showing specific ablation of HSCs with minimal depletion of mature hematopoietic cells in the periphery.

An important clinical application of antibody-based conditioning is autologous gene therapy, which would enable cure of inherited blood diseases via engraftment of genetically corrected HSCs. As a model of autologous gene therapy, we used CRISPR-CRISPR–associated protein 9 ribonucleoproteins to ablate GFP expression from B6-GFP HSCs, then evaluated whether these edited HSCs could convert CD45.2-PBD–conditioned B6-GFP mice to GFP− hematopoiesis (Figure 3D). Using a polyvinyl alcohol–based HSC culture medium,31,32 we successfully maintained CD150+CD48−LSK cells in culture and edited them with >90% efficiency (supplemental Figure 11). These edited HSCs enabled efficient multilineage replacement of GFP+ hematopoiesis in B6-GFP mice conditioned with CD45.2-PBD, but not CD45.1-PBD (Figure 3E). Serial transplantation confirmed that the edited HSCs engrafted by our primary recipients retained the capacity for serial repopulation (supplemental Figure 12).

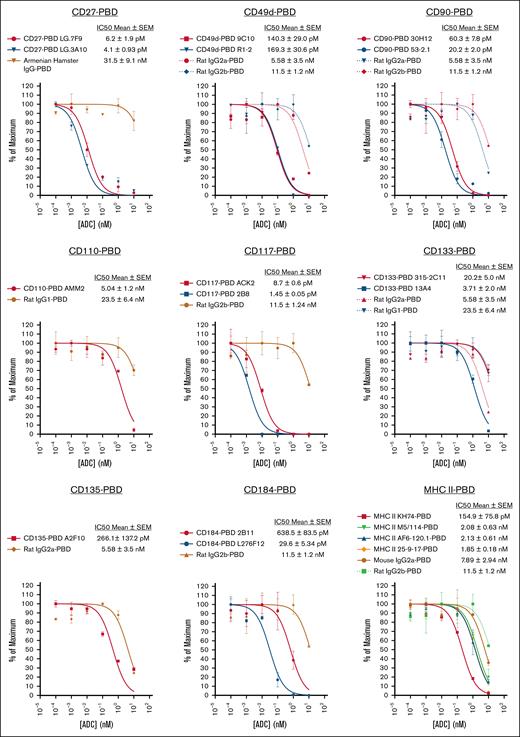

Streamlining ADC screening using SAv-drug conjugates

Because it is generally not possible to predict a priori whether a given antibody-payload combination will be effective for a particular targeting application, robust, efficient screening strategies are key to identifying top-performing candidates. Enabling such rapid preclinical ADC screening is a major practical benefit of our SAv-drug conjugate system. Indeed, we chose to evaluate different drug payloads using SAv-drug conjugates as this approach would enable the most effective payload(s) to proceed directly to ADC screening simply by reacting the appropriate SAv-drug conjugate with any biotinylated antibody. This is a considerably faster and simpler route than directly payload conjugating every antibody one wished to test, an advantage that is most apparent when testing many antibody-payload combinations is desired. To demonstrate this, we used SAv-PBD to perform an in vitro screen of a panel of 22 murine antibodies to identify clones effective as HSC depleting ADCs (Figure 4). This study yielded multiple antibodies and targets worthy of further consideration, including CD27, CD49d, CD90, CD117, and CD184.

SAv-drug conjugates facilitate in vitro ADC cytotoxicity screening to identify effective HSC-depleting antibody clones. A panel of 22 ADCs produced by combining the indicated biotinylated antibodies and isotype controls with SAv-PBD was used for cytotoxicity testing via CFU assay against bone marrow cells from B6 mice. For panels with multiple antibody and isotype control ADCs, curves are color-coded to match each antibody with its respective isotype control. Data points represent mean ± SEM of duplicate CFU plates taken from 1 representative of 2 independent experiments. IC50, 50% inhibitory concentration.

SAv-drug conjugates facilitate in vitro ADC cytotoxicity screening to identify effective HSC-depleting antibody clones. A panel of 22 ADCs produced by combining the indicated biotinylated antibodies and isotype controls with SAv-PBD was used for cytotoxicity testing via CFU assay against bone marrow cells from B6 mice. For panels with multiple antibody and isotype control ADCs, curves are color-coded to match each antibody with its respective isotype control. Data points represent mean ± SEM of duplicate CFU plates taken from 1 representative of 2 independent experiments. IC50, 50% inhibitory concentration.

Evaluation of human CD45-ADCs for targeting HSCs and leukemia cells

After validation of an ADC targeting strategy in fully murine models, conducting similar studies using human cells and humanized mouse models is an important next step. However, many antibodies to mouse antigens do not cross-react with their human counterparts, and it is possible that the optimal payload for depleting the target cell of interest may differ between mouse and human. The SAv-drug conjugate system is well suited to bridging this gap between murine and human studies, enabling the facile production and evaluation of human ADCs using the same SAv-drug conjugates used to evaluate their murine counterparts.

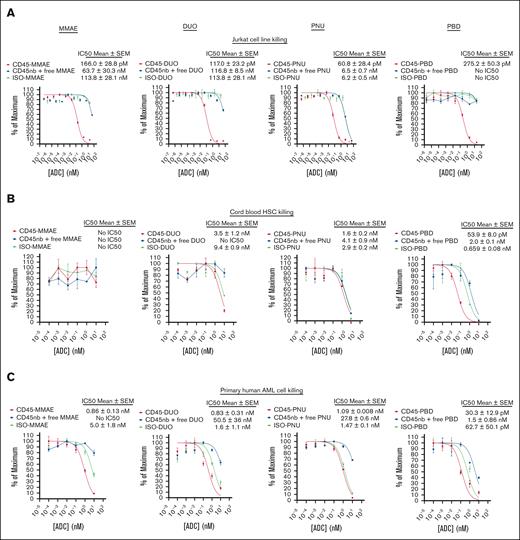

To demonstrate this, we performed cytotoxicity assays using human CD45-ADCs produced with SAv-drug conjugates. We initially screened several CD45 antibodies, demonstrating similar efficacy between clones at targeting Jurkat cells (supplemental Figure 13). We focused our human CD45-ADC studies on clone BC8, the antibody from which 131I-apamistamab was produced,33 given the clinical experience with this antibody and its amino acid sequence being available for antibody engineering.34 CD45 BC8-ADCs made with all 4 payloads yielded similar, picomolar-range 50% inhibitory concentration values when targeting Jurkat cells with CD45-ADCs (Figure 5A). However, in cytotoxicity studies against human HSCs, CD45-PBD was the only ADC tested that specifically inhibited colony formation of cord blood–derived mononuclear cells (Figure 5B). To evaluate CD45-ADC cytotoxicity against primary human leukemia cells, we identified an AML specimen that was successfully passaged in NSG-SGM3 (NSGS)35 mice, which tolerated short-term culture in methylcellulose medium for cytotoxicity testing. CD45-ADCs made with all 4 payloads showed cytotoxicity against these human AML cells, but CD45-PBD was the most potent (Figure 5C).

Human CD45-PBD effectively targets and kills human HSCs and AML cells in vitro. (A-C) Cytotoxicity assays of CD45-ADC produced from anti-CD45 clone BC8 (biotinylated antibody plus SAv-drug conjugate), nb BC8 antibody plus free SAv-drug conjugate, or mouse IgG1-ADC (biotinylated isotype control antibody plus SAv-drug conjugate) against Jurkat cells (A), cord blood derived mononuclear cells (B), and patient-derived leukemia cells (C). Data points represent mean ± SEM of duplicate CFU plates (B) or triplicate wells (A,C) taken from 1 representative of at least 2 independent experiments. IC50, 50% inhibitory concentration; ISO, isotype control; nb, nonbiotinylated.

Human CD45-PBD effectively targets and kills human HSCs and AML cells in vitro. (A-C) Cytotoxicity assays of CD45-ADC produced from anti-CD45 clone BC8 (biotinylated antibody plus SAv-drug conjugate), nb BC8 antibody plus free SAv-drug conjugate, or mouse IgG1-ADC (biotinylated isotype control antibody plus SAv-drug conjugate) against Jurkat cells (A), cord blood derived mononuclear cells (B), and patient-derived leukemia cells (C). Data points represent mean ± SEM of duplicate CFU plates (B) or triplicate wells (A,C) taken from 1 representative of at least 2 independent experiments. IC50, 50% inhibitory concentration; ISO, isotype control; nb, nonbiotinylated.

Unexpectedly, mouse immunoglobulin G1 (IgG1) isotype control antibodies conjugated to all payloads showed greater than anticipated cytotoxicity toward the human AML cells, with a mouse IgG1-PBD conjugate showing a picomolar 50% inhibitory concentration rivaling that of CD45-PBD. This degree of nonspecific toxicity was not observed with human AML cells incubated with nonbiotinylated antibody plus free SAv-drug conjugate, suggesting that this toxicity required the payload to be antibody bound and could not be attributed to the SAv-drug conjugate alone. Given these unexpected results, and that the BC8 antibody has been reported previously to be noninternalizing,36 we performed a series of in vitro fluorescence quenching–based antibody internalization studies to investigate the extent and specificity of BC8 uptake by our target cells. Incubation with biotinylated BC8 bound to SAv-Alexa Fluor 488 (AF488) led all tested cell lines and primary cells to accumulate AF488 fluorescence that was resistant to quenching by an anti-AF488 antibody, demonstrating that the antibody-fluor conjugate was internalized by these cells and, as such, inaccessible to the quenching antibody (supplemental Figure 14A-B). For Jurkat and MOLM13 cells and primary CD34+ cells, BC8-AF488 accumulation was target dependent because it could be blocked by excess unlabeled BC8 antibody. However, BC8 blockade minimally inhibited BC8-AF488 uptake by our primary human AML cells, indicating the activity of a target-independent uptake pathway. We hypothesized that this nonspecific uptake is fragment crystallizable receptor (FcR)-dependent because the human AML cells express CD32 and CD64 (supplemental Figure 14C), and that mouse IgG1 (the isotype of clone BC8) has moderate binding affinity for human CD32.37 Consistently, 3 different mouse IgG1 isotype controls, but not a mouse IgG1 F(ab')2 fragment, showed high levels of nonspecific internalization. Moreover, a mouse IgG2b isotype conjugate, which binds poorly to human FcγR37, was not internalized (supplemental Figure 14D). These data indicate that the nonspecific ADC uptake by our human AML cells occurred via an FcR-dependent mechanism.

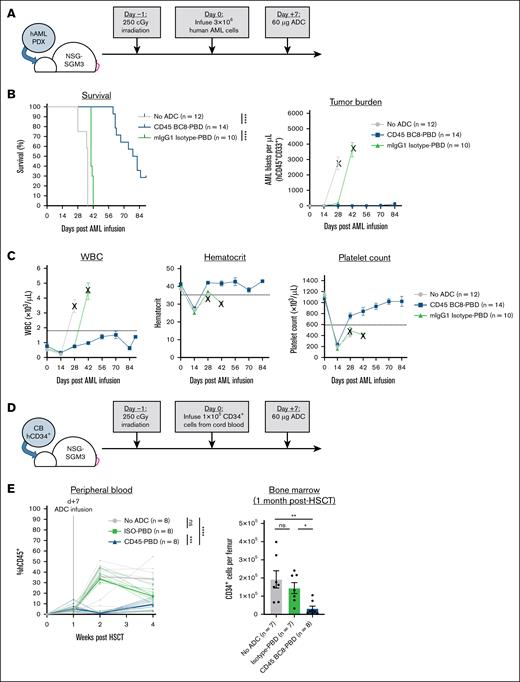

Finally, we tested the ability of CD45-PBD to target human HSCs and patient-derived AML cells in vivo using humanized mouse models. Anti-human CD45 clone BC8 does not cross-react with mouse CD45 or deplete mouse HSCs when PBD-conjugated, allowing administration to mice without needing to provide HSC support. CD45-PBD was highly protective in our human AML xenograft model in NSGS mice, delaying or preventing leukemia cell expansion altogether (Figure 6A-C). Importantly, despite the nonspecific cytotoxicity of mouse IgG1 isotype-PBD toward human AML cells in vitro, the same ADC provided minimal survival benefit in vivo compared with untreated mice. In NSGS mice engrafted with cord blood–derived CD34+ cells (Figure 6D), mice receiving CD45-PBD showed significantly reduced CD34+ counts in the bone marrow and emergence of human mature hematopoietic cells in the peripheral blood (Figure 6E). Taken together, our studies show that CD45-PBD provides the desired therapeutic effects of an ADC-based conditioning regimen for AML, enabling targeting and depletion of both CD34+ HSCs and AML cells.

Human CD45 BC8-PBD produced from SAv-drug conjugates targets human HSCs in vivo and prolongs survival in an AML xenograft model. (A) Schema for PDX AML model in NSGS mice and treatment with CD45-PBD. (B-C) Survival and peripheral blood tumor burden (human CD45+CD33+ cells) (B) and CBCs (C). Death or euthanasia of all individuals in a treatment group is indicated by “X.” One mouse in the CD45 BC8-PBD group that died at day +24 and showed no evidence of leukemia in the blood, spleen, or bone marrow is censored. (D) Schema for engraftment of cord blood–derived CD34+ HSCs in NSGS mice and depletion by CD45-PBD. (E) Frequencies of human CD45+ cells in the peripheral blood and absolute human CD34+ cell counts in the bone marrow of untreated and ADC-treated mice; for peripheral blood data, dotted lines represent individual mice and solid lines are means. One mouse death each in the no-ADC (day +19) and ISO-PBD (day +28) groups occurred before bone marrow CD34+ cell analysis. Numerical data are presented as mean ± SEM of mice from 2 (E) or 3 (B-C) independent experiments. Statistics: Mantel-Cox log-rank test (B), mixed-effects model for repeated measures (E, peripheral blood), 1-way ANOVA with Tukey correction for multiple comparisons (E, bone marrow). ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001. ISO, isotype control; mIgG1, mouse immunoglobulin G1; ns, not significant; PDX, patient-derived xenograft; WBC, white blood cell count.

Human CD45 BC8-PBD produced from SAv-drug conjugates targets human HSCs in vivo and prolongs survival in an AML xenograft model. (A) Schema for PDX AML model in NSGS mice and treatment with CD45-PBD. (B-C) Survival and peripheral blood tumor burden (human CD45+CD33+ cells) (B) and CBCs (C). Death or euthanasia of all individuals in a treatment group is indicated by “X.” One mouse in the CD45 BC8-PBD group that died at day +24 and showed no evidence of leukemia in the blood, spleen, or bone marrow is censored. (D) Schema for engraftment of cord blood–derived CD34+ HSCs in NSGS mice and depletion by CD45-PBD. (E) Frequencies of human CD45+ cells in the peripheral blood and absolute human CD34+ cell counts in the bone marrow of untreated and ADC-treated mice; for peripheral blood data, dotted lines represent individual mice and solid lines are means. One mouse death each in the no-ADC (day +19) and ISO-PBD (day +28) groups occurred before bone marrow CD34+ cell analysis. Numerical data are presented as mean ± SEM of mice from 2 (E) or 3 (B-C) independent experiments. Statistics: Mantel-Cox log-rank test (B), mixed-effects model for repeated measures (E, peripheral blood), 1-way ANOVA with Tukey correction for multiple comparisons (E, bone marrow). ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001. ISO, isotype control; mIgG1, mouse immunoglobulin G1; ns, not significant; PDX, patient-derived xenograft; WBC, white blood cell count.

Discussion

Fifteen ADCs are approved globally for clinical use against solid and hematopoietic cancers, with dozens more currently under evaluation in clinical trials.38 However, many candidate ADCs that showed promise in preclinical studies have not been successfully translated to humans due to inadequate antitumor efficacy and/or unacceptable toxicities. Achieving clinical benefit with an acceptable toxicity profile requires careful optimization of the many variables that affect ADC function against a given target cell type, including the antibody, target antigen, drug payload and conjugation ratio, payload conjugation and linker chemistry, and the conjugate’s in vivo pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic properties.39 Methods that facilitate preclinical ADC optimization, encompassing both in vitro and in vivo modeling, are essential to clinical translation of successful ADC candidates.

To achieve that end, we developed a simple, robust method for conjugating multiple different small-molecule ADC payloads to SAv, providing a rapid and cost-effective pathway to ADC production that is accessible to virtually any laboratory equipped for molecular biology. We envision that this screening platform will provide the greatest practical benefit to researchers interested in evaluating many combinations of antibody and/or payload; rather than directly conjugating every antibody and payload one wished to test, a wide array of ADCs can be generated via a 15-minute reaction between an SAv-drug conjugate and any biotinylated antibody. Furthermore, SAv may also be conjugated to novel noncytotoxic payloads, enabling rapid testing of antibody conjugates with agents such as antibiotics,40 oligonucleotides,41 immunomodulators,42 CRISPR ribonucleoproteins,43 or proteolysis targeting chimeras.44

Biotin-Sav–based ADC screening strategies have been described previously but have limitations, which we sought to address. Commercial SAv-saporin conjugates, although instrumental to our previous demonstration of chemotherapy- and irradiation-free allo-HSCT conditioning,19 yielded ADCs that provided minimal antitumor benefit in murine lymphoma or AML models.12,20 Furthermore, the immunogenicity of saporin and its association with adverse events such as vascular leak syndrome would limit the clinical utility of ADCs made with this payload.45,46 Our desire to evaluate multiple payloads other than saporin, then directly advance the top candidates to further in vitro and in vivo ADC screening, were the main issues for which producing our own SAv-drug conjugates provided a practical solution. Another method combining SAv-conjugated antibodies with biotinylated payloads was recently shown to yield effective ADCs.47 However, a drawback of this approach is that relatively few payloads are available in biotinylated format; by contrast, a SAv-conjugated payload can readily take advantage of the wide array of available biotinylated antibodies.

The PBD dimer SGD-1882 was the most effective payload of those tested for targeting mouse and human HSCs and leukemia cells, despite SAv-PBD having the lowest drug-SAv conjugation ratio. The extremely high potency of PBD dimers, coupled with their known myelotoxicity, activity against both dividing and quiescent cells,48 and capacity for bystander toxicity may have enabled potent target killing even with low drug exposure. Conversely, CD45.2-MMAE showed minimal cytotoxicity against all tested murine cell types despite the known efficacy of anti-CD45.2 clone 104 as an ADC. Because the biotin-binding function of SAv-MMAE was unaffected by the conjugation (supplemental Figure 3) and human CD45-ADCs made with SAv-MMAE were cytotoxic toward human cells, our data suggest that the poor activity of CD45.2-MMAE toward murine cells is likely due a relative insensitivity to the MMAE payload, which other studies have documented.49,50

We are pursuing several technical optimizations that will address limitations of the current platform and improve its utility in the future. First, although cathepsin-cleavable valine-based linkers are stable in human plasma, they are cleavable by the mouse plasma enzyme carboxylesterase 1C (CES1c),51 potentially leading to toxicities from premature payload release that could affect whether a candidate ADC advances to further testing. This can be circumvented by either using CES1c-deficient mice,52 or by incorporating ADC linkers with acidic N-terminal residues that are resistant to CES1c but remain sensitive to cathepsin-mediated cleavage.53 Alternatively, noncleavable linkers54 can improve ADC stability in plasma but may impede payload release by requiring target cells to first degrade the antibody intracellularly. Previous reports have demonstrated the efficacy of noncleavable PBD-based HER2-, CD22-, and CD45-ADCs in vitro and in vivo.55,56

A second unexplored application of our SAv-drug conjugate system is the production of dual-payload ADCs. Synergistic combinations of ADC payloads with different mechanisms of action can improve antitumor efficacy and reduce the chance of development of escape variants. Our existing SAv-drug conjugate system could be adapted for use in dual-payload ADCs by direct maleimide-thiol conjugation of the first payload to a biotinylated antibody, followed by indirect conjugation of the second payload using a SAv-drug conjugate. Alternatively, because SAv natively lacks cysteine residues, SAv engineered with N-terminal cysteines and functionalized with azide groups could support installation of dual payloads via sequential maleimide-thiol and Click reactions, respectively.

In summary, harnessing the considerable therapeutic potential of ADCs depends critically on identifying conjugates that strike an optimal balance between efficacy and toxicity. Our study highlights PBD as a highly effective payload for targeting mouse and human HSCs and AML cells in the context of HSCT conditioning. Notably, our study offers tools that will enable any laboratory, particularly those embarking on preclinical research involving ADCs, to develop their own targeting strategies that will advance the ongoing effort of translating ADC-based therapies to the clinic.

Acknowledgments

Acute myeloid leukemia 1 (AML1) primary cells were a kind gift from Timothy Ley. Mass spectrometry analyses of streptavidin-drug conjugation ratios were performed by the Mass Spectrometry Technology Access Center at the McDonnell Genome Institute at Washington University School of Medicine (supported by the Diabetes Research Center, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, National Institutes of Health [NIH] grant P30DK020579, Institute of Clinical and Translational Sciences, National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, NIH Clinical and Translational Science Award UL1TR002345, and Siteman Cancer Center., National Cancer Institute (NCI), NIH Cancer Center Support Grant (CCSG) P30CA091842). Liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry analysis of free payload was performed by the Washington University Metabolomics Facility. The authors thank the Alvin J. Siteman Cancer Center at Washington University School of Medicine and Barnes-Jewish Hospital for access to the Siteman Flow Cytometry core facility (supported, in part, by NCI/NIH CCSG grant P30CA091842).

This study was funded by NCI/NIH grant R35CA210084 (J.F.D.; including a research supplement to promote diversity [S.P.P.]), NCI/NIH Leukemia SPORE grant (P50CA171963; J.F.D.), NCI/NIH Leukemia SPORE Career Enhancement and Developmental Research Awards (P50CA171063; S.P.P.), an American Society for Transplantation and Cellular Therapy New Investigator Award (S.P.P.), an American Society of Hematology Scholar Award (S.P.P.), awards from Gabrielle’s Angel Foundation for Cancer Research (S.P.P.), and an NCI/NIH Research Specialist Award (5R50CA211466; M.P.R).

Authorship

Contribution: S.P.P. conceived the research and led the project under the mentorship of J.F.D.; A.R.Y., J.K.R., and S.P.P. performed all experiments; E.C. and M.P.R. developed and optimized the human acute myeloid leukemia xenograft model used in this study; A.R.Y. and S.P.P. wrote the manuscript; and all authors read and approved the manuscript and order of the author list before submission.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: J.F.D. reports equity stock/ownership with Magenta Therapeutics and Wugen; reports consulting fees from Incyte and RiverVest Venture Partners; reports research funding from NeoImmuneTech, MacroGenics, Incyte, BioLineRx, and Wugen; and holds patents with Wugen. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Stephen P. Persaud, Pathology and Immunology, Washington University School of Medicine, 660 S Euclid Ave, MSC 8118-0066-06, St. Louis, MO 63110; email: persaud@wustl.edu.

References

Author notes

The data sets generated and analyzed during the study are available from the corresponding author, Stephen P. Persaud (persaud@wustl.edu), on reasonable request.

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.