Key Points

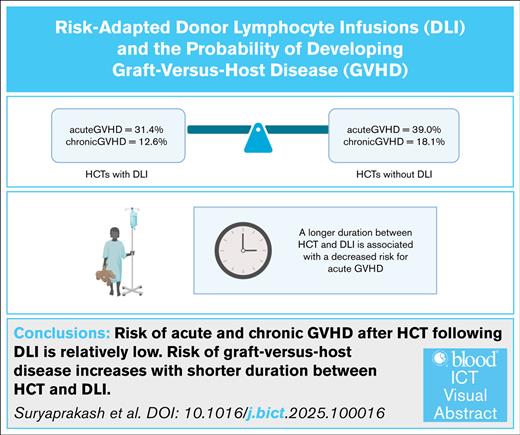

Risk of acute and chronic GVHD after HCT after DLI is relatively low.

Risk of GVHD increases with shorter duration between HCT and DLI.

Visual Abstract

Donor lymphocyte infusion (DLI) enhances the graft-versus-leukemia effect and can prevent graft rejection after an allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplant (HCT), but its use is limited by the risk of graft-versus-host disease (GVHD). From 2005 to 2021, 179 patients received 191 HCTs, followed by ≥1 DLIs (n = 626), and 561 patients received 608 HCTs without subsequent DLI. Among DLI recipients, 31.4% and 12.6% developed acute GVHD (aGVHD) and chronic GVHD (cGVHD), respectively, compared with 39% and 18.1%, respectively, of HCT recipients who did not receive DLI (P = .06 for aGVHD, P = .08 for cGVHD). A longer interval between HCT and DLI was associated with a decreased risk of aGVHD. The overall response to DLI for mixed chimerism was 45.2% for HCTs using matched sibling donors, 33.3% for HCTs using matched unrelated donors, and 43.1% for haploidentical HCTs. In our study, the incidence of GVHD among pediatric HCT recipients was similar regardless of whether they received DLI after HCT or not. The risk of GVHD decreased as the interval between HCT and DLI increased, and there was an encouraging response rate for patients receiving DLI for mixed chimerism. Hence, DLI offers a potential therapeutic option for patients with impending graft rejection.

Introduction

An allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplant (HCT) is a therapeutic option for patients with high-risk hematological malignancies or nonmalignant diseases. Despite improvements in supportive care and survival over the last decade, disease relapse remains the primary cause of post-HCT mortality for individuals with hematological malignancies.1 Additionally, recipients of HCTs for nonmalignant disorders often experience graft rejection and disease recurrence.2 Donor lymphocyte infusion (DLI) is a form of adoptive immunotherapy wherein donor T lymphocytes are infused to potentiate the graft-versus-leukemia effect in patients who experience leukemia relapse.3 DLI has also been used to prevent graft rejection in HCT recipients with declining donor chimerism and impending graft rejection during treatment for malignant and nonmalignant disorders.4,5 DLI is easily administered and is associated with a lower risk of graft ablation when compared with other chemotherapeutic options for preventing leukemia relapse or graft rejection.

Although DLI has proved effective in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia, its efficacy in patients with acute leukemia has historically been suboptimal,3,6,7 and its use has been further constrained by the risk of acute or chronic graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) developing in patients receiving DLI,8 especially in those with nonmalignant hematological disorders. In addition, the timing of administration and the optimal dose of DLI remain poorly understood, especially for pediatric patients. Accordingly, we conducted a retrospective, single-center study to evaluate the efficacy and toxicity of DLI after HCT with the goal of identifying factors influencing the risk of GVHD.

Methods

Patients

The study was approved by the institutional review board at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital and adhered to the ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. Patients who received an HCT between 2005 and 2021 at this institution were eligible for the study. Those patients who received a transplant from a matched sibling donor (MSD), a matched unrelated donor (MUD), or a haploidentical donor (HAPLO) for nonmalignant disease or a malignant disorder, except for a solid tumor, were included in the study. Patients who received an investigational protocol–directed CD45RA-depleted DLI and those with active malignant disease at the time of HCT were excluded from the data set. Additionally, patients with active GVHD at, or before, the time of their first DLI were excluded from the analysis to assess the efficacy or safety of DLI. All HCTs were considered as independent events in the analysis, and some patients received multiple HCTs.

Clinical data retrieved included patient demographics (age, sex, and race), the initial diagnosis, donor-related factors (donor type, cell source, cytomegalovirus serostatus of the donor and recipient, and blood group incompatibility between the donor and recipient), DLI-related factors (dose of first DLI, number of days from HCT to first DLI, and total number of DLIs received), and the year/decade in which the HCT was performed. Outcome variables included the incidence of acute GVHD (aGVHD) and chronic GVHD (cGVHD), serial blood donor chimerism, measurable residual disease (MRD), the incidence of relapse, and overall survival (OS) after HCT.

Chimerism and MRD testing

Recipient/donor chimerism before 2014 was evaluated using a combination of laboratory-developed variable number tandem repeat analysis and commercial short tandem repeat (Identifiler, Life Technologies) analyses.9 From 2014 onward, chimerism was performed by short tandem repeat analysis (PowerPlex21, Promega).10 The validated detection and quantitation limits for these methods are 1% and 5% host chimerism, respectively. Chimerism was assessed in all HCT recipients weekly until day +100, monthly until the first annual visit, and then yearly. MRD was assessed using multiparameter flow cytometry or appropriate cytogenetic or molecular markers.11 Bone marrow MRD was routinely assessed at day +30, day +100, and 1 year after HCT or more frequently in patients with a clinical concern for disease recurrence.

DLI protocol

The institutional schema for administering DLI has been described previously.12 DLI was considered when 2 consecutive tests revealed mixed donor chimerism, when a mixed chimerism test was accompanied by evidence of viral reactivation, or when there was evidence of detectable MRD. The starting dose of DLI was based on the risk of GVHD based on the donor source. Generally, the first DLIs comprised 1 × 105, 1 × 106, and 1 × 107 CD3+ cells per kg for recipients of HAPLO, MUD, and MSD transplants, respectively. Subsequent DLI doses were escalated conservatively by a twofold increment. Repeated DLI every 2 to 4 weeks was given only to patients with persistent mixed chimerism and was stopped immediately when the chimerism reverted to 100% donor, thus limiting the risk of GVHD.12

Definitions

Mixed chimerism was defined as 2 consecutive tests revealing chimerism that was ≤99% donor. Response to DLI for mixed chimerism/graft failure was defined as 100% donor chimerism being attained within 180 days after the first DLI. Similarly, response to DLI for disease relapse was defined as a decrease in MRD within 180 days after the first DLI. aGVHD was defined based on the consensus criteria,13 and cGVHD was defined based on the National Institutes of Health global scoring system.14

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables are presented as the median (range) and are compared using the Wilcoxon Mann-Whitney or Kruskal-Wallis tests as appropriate. Categorical variables are presented as counts (percentages) and are compared using the Fisher exact test. Competing-risk regression models using the Fine-Gray method were developed to evaluate risk factors for aGVHD and cGVHD after the first DLI. The following variables were considered in the analysis: patient age at time of transplant, diagnosis, stem cell product source, number of DLIs administered, interval from HCT to first DLI, and CD3+ cell dose of first DLI. Death and relapse were considered as competing risk events for these GVHD outcomes. Follow-up data were censored at subsequent transplant, at 2 years after the first DLI, at 5 years after HCT, or at last follow-up, whichever occurred first. The Kaplan-Meier method and the log-rank test were used to examine differences in OS and event-free survival (EFS) among patients who developed GVHD after DLI. Landmark analysis of the cumulative incidence of aGVHD and cGVHD was performed based on the timing of DLI. Cox proportional hazard models were used to estimate the risk factors affecting OS and EFS after DLI. Logistic regression analysis was performed to assess factors associated with the response to DLI within 180 days after the first DLI. All statistical analyses were performed using R version 4.3, and a P value <.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

Results

Demographics

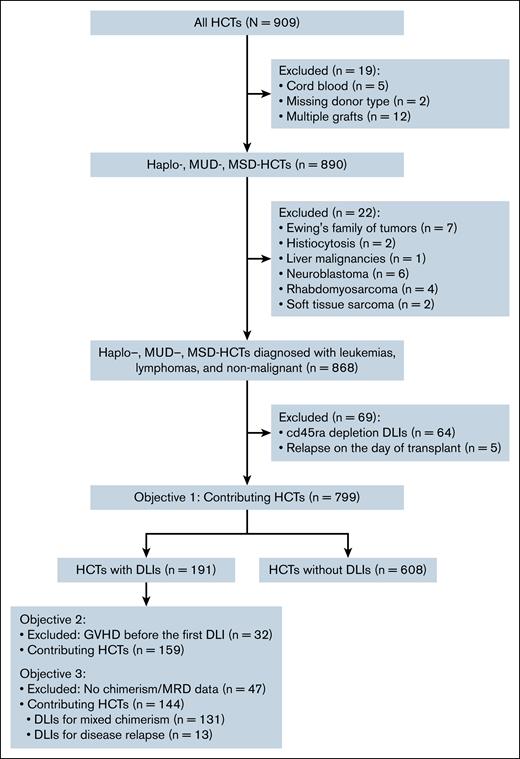

Each HCT was treated as an independent unit for this analysis. A total of 799 HCTs met the inclusion criteria for the study (Figure 1). Of these, 191 were performed in 179 patients who subsequently received a DLI, and 608 were performed in 561 patients who did not subsequently receive a DLI. The median age of patients at the time of transplant was 9.5 years (range, 0.2-25.2) for HCT with subsequent DLI and 10.5 years (range, 0.1-27.2) for HCT without subsequent DLI (P = .04; Table 1). Baseline characteristics of race, sex, and number of transplants were similarly distributed for both groups. HCTs with subsequent DLI were more frequently performed in recent years (P = .05) and were more likely to be from HAPLOs (P < .001) when compared with HCTs without subsequent DLI.

Characteristics and clinical outcomes of HCTs with and without DLI

| Patient characteristics . | HCTs with DLI (n = 191) . | HCTs without DLI (n = 608) . | P . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at transplant (y) | .04 | ||

| Median (range) | 9.5 (0.2-25.2) | 10.5 (0.1-27.2) | |

| Sex | .74 | ||

| Female | 83 (43.5%) | 255 (41.9%) | |

| Race | .57 | ||

| White | 142 (74.3%) | 451 (74.2%) | |

| African ancestry | 35 (18.3%) | 99 (16.3%) | |

| Other | 14 (7.3%) | 58 (9.5%) | |

| Diagnosis | .05 | ||

| ALL | 51 (26.7%) | 187 (30.8%) | |

| AML | 82 (42.9%) | 215 (35.4%) | |

| Other leukemia | 19 (9.9%) | 58 (9.5%) | |

| Lymphoma | 3 (1.6%) | 37 (6.1%) | |

| Nonmalignant disorder | 36 (18.8%) | 111 (18.3%) | |

| Donor type | <.001 | ||

| MSD | 44 (23.0%) | 113 (18.6%) | |

| MUD | 53 (27.7%) | 264 (43.4%) | |

| HAPLO | 94 (49.2%) | 231 (38.0%) | |

| Transplant number | .76 | ||

| 1 | 151 (79.1%) | 472 (77.9%) | |

| >2 | 40 (20.9%) | 134 (22.1%) | |

| Transplant year | .05 | ||

| 2005-2009 | 43 (22.5%) | 193 (31.7%) | |

| 2010-2015 | 81 (42.4%) | 225 (37.0%) | |

| 2016-2021 | 67 (35.1%) | 190 (31.3%) | |

| aGVHD | |||

| Grade 1-4 aGVHD | 60 (31.4%) | 237 (39.0%) | .06 |

| Grade 2-4 aGVHD | 40 (21.1%) | 159 (26.4%) | .15 |

| cGVHD | 24 (12.6%) | 110 (18.1%) | .08 |

| Relapse | 56 (29.3%) | 122 (20.1%) | .01 |

| Death | 75 (39.3%) | 237 (39.0%) | .99 |

| Patient characteristics . | HCTs with DLI (n = 191) . | HCTs without DLI (n = 608) . | P . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at transplant (y) | .04 | ||

| Median (range) | 9.5 (0.2-25.2) | 10.5 (0.1-27.2) | |

| Sex | .74 | ||

| Female | 83 (43.5%) | 255 (41.9%) | |

| Race | .57 | ||

| White | 142 (74.3%) | 451 (74.2%) | |

| African ancestry | 35 (18.3%) | 99 (16.3%) | |

| Other | 14 (7.3%) | 58 (9.5%) | |

| Diagnosis | .05 | ||

| ALL | 51 (26.7%) | 187 (30.8%) | |

| AML | 82 (42.9%) | 215 (35.4%) | |

| Other leukemia | 19 (9.9%) | 58 (9.5%) | |

| Lymphoma | 3 (1.6%) | 37 (6.1%) | |

| Nonmalignant disorder | 36 (18.8%) | 111 (18.3%) | |

| Donor type | <.001 | ||

| MSD | 44 (23.0%) | 113 (18.6%) | |

| MUD | 53 (27.7%) | 264 (43.4%) | |

| HAPLO | 94 (49.2%) | 231 (38.0%) | |

| Transplant number | .76 | ||

| 1 | 151 (79.1%) | 472 (77.9%) | |

| >2 | 40 (20.9%) | 134 (22.1%) | |

| Transplant year | .05 | ||

| 2005-2009 | 43 (22.5%) | 193 (31.7%) | |

| 2010-2015 | 81 (42.4%) | 225 (37.0%) | |

| 2016-2021 | 67 (35.1%) | 190 (31.3%) | |

| aGVHD | |||

| Grade 1-4 aGVHD | 60 (31.4%) | 237 (39.0%) | .06 |

| Grade 2-4 aGVHD | 40 (21.1%) | 159 (26.4%) | .15 |

| cGVHD | 24 (12.6%) | 110 (18.1%) | .08 |

| Relapse | 56 (29.3%) | 122 (20.1%) | .01 |

| Death | 75 (39.3%) | 237 (39.0%) | .99 |

P values <.05 are in bold font.

ALL, acute lymphoblastic leukemia; AML, acute myeloid leukemia.

GVHD and relapse among patients who received DLI

We compared the incidence of GVHD among all HCT recipients, irrespective of the indications for DLI or the number of doses of DLI administered. There was no significant difference in the overall incidence of any grade of aGVHD or in that of specifically grade 2 to 4 aGVHD between HCTs performed with and without subsequent DLI (incidence of any grade of aGVHD: 31.4% vs 39.0%, P = .06; incidence of grade 2-4 aGVHD: 21.1% vs 26.4%, P = .15). Likewise, the incidence of cGVHD did not differ significantly between the 2 groups (12.6% vs 18.1%, P = .08). A subgroup analysis to account for potential variation by donor type found that the incidence of aGVHD after HAPLO HCT was significantly lower when DLI was administered (30.9% vs 45.5%, P = .02; supplemental Table 1). In contrast, there was no significant difference in the incidence of aGVHD after MSD or MUD HCT according to whether or not DLI was administered (25.0% vs 25.7% for MSD HCT, 37.7% vs 39% for MUD HCT; P > .99 for both). Additionally, there was no significant difference in the incidence of cGVHD by donor type according to whether the recipients did or did not subsequently receive DLI (6.8% vs 15% for MSD HCT, P = .19; 9.4% vs 13.6% for MUD HCT, P = .51; 17% vs 24.7% for HAPLO HCT, P = .15).

The incidence of relapse was significantly higher for HCT with subsequent DLI than for HCT without DLI (29.3% vs 20.1%, P = .009), but there was no difference in the mortality rate between the 2 groups (39.3% vs 39.0%, P > .99). Among HCTs after which DLI was administered for viral reactivation or poor immune recovery, the relapse rate was 40%. Of 15 patients who received DLI for viral reactivation, 8 showed improvement in their viral load after DLI, whereas 7 did not. The incidence of death secondary to infection was significantly lower for HCT with subsequent DLI than for HCT without DLI (6.7% vs 20.9%, P = .001; supplemental Table 2).

DLI safety and efficacy evaluation cohort

For the subsequent analysis of the efficacy and safety of DLI, 32 HCT recipients with active GVHD at, or before, the time of first DLI were excluded (Figure 1). This left 159 HCTs for which DLI was administered, of which 40 were from an MSD, 37 from an MUD, and 82 from a HAPLO. Among these, serotherapy was a component of the conditioning regimen for 132 HCTs and a T-cell–depleted graft was administered for 40 HCTs. Among HCTs performed for underlying malignant diagnoses, immunosuppression was rapidly weaned off before administration of DLI in all cases. Among 36 HCTs performed for nonmalignant diseases, immunosuppression was rapidly weaned off before DLI administration in 15 cases whereas the remaining 21 patients continued immunosuppression during DLI administration. A single DLI was administered after 45 HCTs, whereas ≥2 DLIs were administered after 114 HCTs. The median time to first DLI after HCT was 88 days (range, 35-1581) for MSD HCT, 109 days (range, 42-778) for MUD HCT, and 64 days (range, 0-1610 days) for HAPLO HCT. The median number of DLIs administered was 2 (range, 1-9) after MSD HCT, 3 (range, 1-7) after MUD HCT, and 3 (range, 1-14) after HAPLO HCT, with a median first CD3+ dose of 10.00 × 106/kg (range, 0.03 × 106 to 50.00 × 106/kg) after MSD HCT, 1.00 × 106/kg (range, 0.01 × 106 to 10.00 × 106/kg) after MUD HCT, and 0.05 × 106/kg (range, 0.03 × 106 to 10.00 × 106/kg) after HAPLO HCT.

Therapeutic response after DLI

We evaluated response to DLI based on whether DLI was administered for mixed chimerism or for resurgence of low-level MRD. Data on clinical response after DLI were available for 131 HCT with DLI based on chimerism but for only 13 HCTs based on MRD (Figure 1). Among patients who received DLI for mixed chimerism (n = 131 HCTs), the median chimerism before and after DLI was 99% (range, 11%-100%) and 99% (range, 0%-100%), respectively. Among these patients the overall response rate was 45.2% for MSD HCTs, 33.3% for MUD HCTs, and 43.1% for HAPLO HCTs. On logistic regression, patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia (hazard ratio [HR], 5.93; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.73-20.27; P = .005) or acute myeloid leukemia (HR, 5.56; 95% CI, 1.78-17.38; P = .003) who received DLI for mixed chimerism (Table 2) had better response rates than patients with nonmalignant disorders (the reference group). Other factors such as the patient age at transplant, donor type, decade in which the transplant was performed, interval between HCT and DLI, and dose of DLI were not associated with response to DLI for mixed chimerism (Table 2). Patients who responded to DLI for mixed chimerism had a lower mortality rate when compared with nonresponders (17% vs 30.8%, P = .10); this was not statistically significant.

Risk factors associated with response to DLI for mixed chimerism by transplant donor types

| Variables . | HR∗ (95% CI) . | P value . |

|---|---|---|

| Age at transplant | 1.03 (0.97-1.10) | .33 |

| Transplant year | ||

| 2005-2009 (reference) | ||

| 2010-2015 | 2.07 (0.76-5.59) | .15 |

| 2016-2021 | 1.29 (0.45-3.67) | .64 |

| Diagnosis | ||

| Nonmalignant (reference) | ||

| ALL | 5.93 (1.73-20.27) | .005 |

| AML | 5.56 (1.78-17.38) | .003 |

| Other leukemias | 3.20 (0.73-14.03) | .12 |

| Days from HCT to DLI | 1.00 (1.00-1.00) | .57 |

| CD3+ cell dose (first DLI) | 1.02 (0.94-1.09) | .65 |

| Variables . | HR∗ (95% CI) . | P value . |

|---|---|---|

| Age at transplant | 1.03 (0.97-1.10) | .33 |

| Transplant year | ||

| 2005-2009 (reference) | ||

| 2010-2015 | 2.07 (0.76-5.59) | .15 |

| 2016-2021 | 1.29 (0.45-3.67) | .64 |

| Diagnosis | ||

| Nonmalignant (reference) | ||

| ALL | 5.93 (1.73-20.27) | .005 |

| AML | 5.56 (1.78-17.38) | .003 |

| Other leukemias | 3.20 (0.73-14.03) | .12 |

| Days from HCT to DLI | 1.00 (1.00-1.00) | .57 |

| CD3+ cell dose (first DLI) | 1.02 (0.94-1.09) | .65 |

P values <.05 are in bold font.

Abbreviations are explained in Table 1.

Adjusted for transplant type.

For disease relapse, the response rates were 50%, 0%, and 57.1% for MSD HCTs, MUD HCTs, and HAPLO HCTs, respectively. Further statistical analyses for disease relapse were not performed because of the limited number of patients (n = 13).

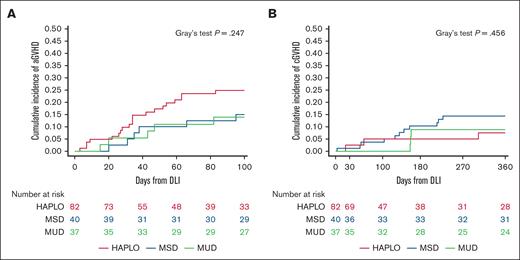

GVHD after DLI

Of 159 HCT recipients without active GVHD at, or before, the time of first DLI, GVHD subsequently occurred in 38 (23.9%) after DLI. Of these, aGVHD was documented in 34 (21.4% of the total) and cGVHD in 17 (10.7% of the total). The cumulative incidence of aGVHD at 100 days after the first DLI was 15.0% (95% CI, 3.9-26.1) for MSD HCTs, 14.0% (95% CI, 2.6-25.3) for MUD HCTs, and 24.8% (95% CI, 15.4-34.3) for HAPLO HCTs, whereas the cumulative incidence of cGVHD within 360 days after the first DLI was 7.6% (95% CI, 0-15.8) for MSD HCTs, 8.9% (95% CI, 0-18.4) for MUD HCTs, and 14.4% (95% CI, 6.5-22.3) for HAPLO HCTs, with no significant difference being observed among the different donor groups (P = .25 for aGVHD and P = .46 for cGVHD; Figure 2). There was no significant association between the number of DLIs administered and the onset of aGVHD (P = .12) or cGVHD (P = .71; supplemental Table 3). Similarly, receiving serotherapy or T-cell–depleted graft were not associated with the incidence of aGVHD (P = .5 for serotherapy and P = .19 for T-cell depletion) or cGVHD (P = .81 for serotherapy and P > .99 for T-cell depletion). Hereafter, we describe the results of our univariate, competing risk, and landmark analyses for risk of developing aGVHD or cGVHD.

DLIs from HAPLOs, MSDs, and MUDs induce similar rates of aGVHD and cGVHD. Cumulative incidence of aGVHD (A) and cGVHD (B) in recipients of HAPLO, MSD, or MUD HCTs after administration of the first DLI. P = .25 for aGVHD, P = .46 for cGVHD (Gray's test).

DLIs from HAPLOs, MSDs, and MUDs induce similar rates of aGVHD and cGVHD. Cumulative incidence of aGVHD (A) and cGVHD (B) in recipients of HAPLO, MSD, or MUD HCTs after administration of the first DLI. P = .25 for aGVHD, P = .46 for cGVHD (Gray's test).

Univariate analysis

In univariate analysis of HAPLO HCTs, a longer interval between HCT and DLI was associated with a decreased risk of aGVHD (HR, 0.98; 95% CI, 0.96-0.99; P = .007). For MSD and MUD HCTs (analyzed together), receiving a bone marrow graft was associated with a decreased risk of aGVHD (HR, 0.2; 95% CI, 0.06-0.62; P = .006) and a longer interval between HCT and DLI infusion was associated with a decreased risk of aGVHD (HR, 0.98; 95% CI, 0.96-0.99; P < .001) and cGVHD (HR, 0.99; 95% CI, 0.99-1.00; P = .009) (supplemental Table 4).

Competing risk analysis

In a competing risk analysis after adjusting for transplant type, a longer interval between HCT and DLI continued to be associated with a decreased risk of aGVHD (HR, 0.98; 95% CI, 0.96-0.99; P < .001; Table 3). No significant risk factors for developing cGVHD were identified.

Competing risk analysis after DLI: impact of donor source as a covariate

| Variables . | aGVHD . | cGVHD . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR∗ (95% CI) . | P value . | HR∗ (95% CI) . | P value . | |

| Age at transplant | 0.99 (0.93-1.06) | .83 | 0.97 (0.90-1.06) | .53 |

| Transplant year | ||||

| 2005-2009 (reference) | ||||

| 2010-2015 | 1.21 (0.48-3.08) | .68 | 0.81 (0.24-2.72) | .74 |

| 2016-2021 | 1.57 (0.63-3.92) | .34 | 1.15 (0.35-3.75) | .82 |

| Diagnosis | ||||

| ALL (reference) | ||||

| AML | 2.12 (0.81-5.49) | .12 | 2.68 (0.74-9.79) | .14 |

| Other leukemias | 2.50 (0.77-8.12) | .13 | 2.10 (0.34-12.97) | .50 |

| Nonmalignant | 0.84 (0.24-3.03) | .80 | 0.46 (0.05-3.95) | .48 |

| Days from HCT to DLI | 0.98 (0.96-0.99) | <.001 | 0.99 (0.97-1.00) | .06 |

| CD3+ cell dose (first DLI) | 0.93 (0.84-1.03) | .17 | 1.03 (0.98-1.09) | .21 |

| Cell source | ||||

| PBSC (reference) | ||||

| BM | 0.41 (0.07-2.38) | .32 | 1.13 (0.10-12.90) | .92 |

| Variables . | aGVHD . | cGVHD . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR∗ (95% CI) . | P value . | HR∗ (95% CI) . | P value . | |

| Age at transplant | 0.99 (0.93-1.06) | .83 | 0.97 (0.90-1.06) | .53 |

| Transplant year | ||||

| 2005-2009 (reference) | ||||

| 2010-2015 | 1.21 (0.48-3.08) | .68 | 0.81 (0.24-2.72) | .74 |

| 2016-2021 | 1.57 (0.63-3.92) | .34 | 1.15 (0.35-3.75) | .82 |

| Diagnosis | ||||

| ALL (reference) | ||||

| AML | 2.12 (0.81-5.49) | .12 | 2.68 (0.74-9.79) | .14 |

| Other leukemias | 2.50 (0.77-8.12) | .13 | 2.10 (0.34-12.97) | .50 |

| Nonmalignant | 0.84 (0.24-3.03) | .80 | 0.46 (0.05-3.95) | .48 |

| Days from HCT to DLI | 0.98 (0.96-0.99) | <.001 | 0.99 (0.97-1.00) | .06 |

| CD3+ cell dose (first DLI) | 0.93 (0.84-1.03) | .17 | 1.03 (0.98-1.09) | .21 |

| Cell source | ||||

| PBSC (reference) | ||||

| BM | 0.41 (0.07-2.38) | .32 | 1.13 (0.10-12.90) | .92 |

P values <.05 are in bold font.

ALL, acute lymphoblastic leukemia; AML, acute myeloid leukemia; BM, bone marrow; PBSC, peripheral blood stem cells.

Adjusted for transplant type.

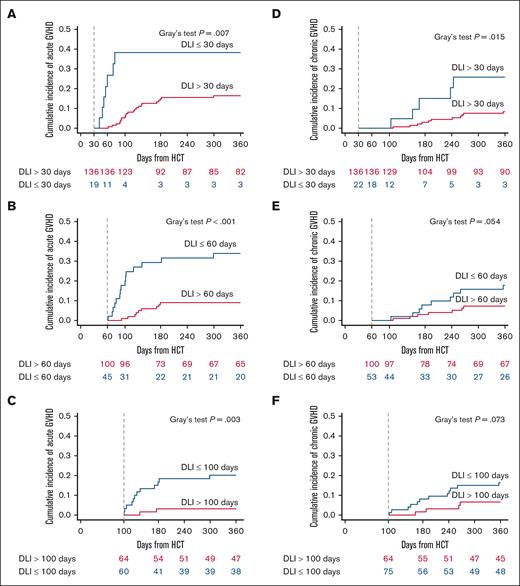

Landmark analysis

A landmark analysis of the cumulative incidence of aGVHD and cGVHD was performed based on the timing of DLI at 30, 60, and 100 days after HCT. This analysis demonstrated that earlier DLI was associated with a higher risk of developing aGVHD. Specifically, for DLI administered within 30 days after HCT, the incidence of aGVHD was 38.3% (95% CI, 15.9-60.7), compared with 14.8% (95% CI, 8.8-20.8) for DLI administered after 30 days (P = .007). Similar trends were seen for DLI administered within 60 days (29.2% [95% CI, 15.9-42.6]) vs after 60 days (9.1% [95% CI, 3.4-14.7]; P < .001), and for DLI given within 100 days (16.7% [95% CI, 7.3-26.2]) vs after 100 days (3.2% [95% CI, 0-7.5]; P = .003).

In contrast, an increased risk of cGVHD at 180 days was observed only when DLI was administered within 30 days after HCT (15% [95% CI, 0-30.7], compared with 3% [95% CI, 0.1-5.9]) when DLI was administered after 30 days (P = .02). This difference was not observed for DLI administered within 60 days after HCT (7.8% [95% CI, 0.5-15.2]) vs after 60 days (3% [95% CI, 0-6.4]; P = .05) or for DLI given within 100 days (8.1% [95% CI, 1.9-14.4]) vs after 100 days (1.6% [95% CI, 0-4.7]; P = .07; Figure 3).

The risk of developing aGVHD or cGVHD depends on the timing of DLI. Landmark analysis of DLI at 30, 60, and 100 days after HCT for development of aGVHD (A-C) and cGVHD (D-F). For aGVHD, P = .007 for DLI day <30 vs ≥30; P < .001 for DLI day <60 vs ≥60, and P = .003 for DLI day <100 vs ≥100 (Gray's test). For cGVHD, P = .015 for DLI day <30 vs ≥30: P = .054 for DLI day <60 vs ≥60; P = .073 for DLI day <100 vs ≥100 (Gray's test).

The risk of developing aGVHD or cGVHD depends on the timing of DLI. Landmark analysis of DLI at 30, 60, and 100 days after HCT for development of aGVHD (A-C) and cGVHD (D-F). For aGVHD, P = .007 for DLI day <30 vs ≥30; P < .001 for DLI day <60 vs ≥60, and P = .003 for DLI day <100 vs ≥100 (Gray's test). For cGVHD, P = .015 for DLI day <30 vs ≥30: P = .054 for DLI day <60 vs ≥60; P = .073 for DLI day <100 vs ≥100 (Gray's test).

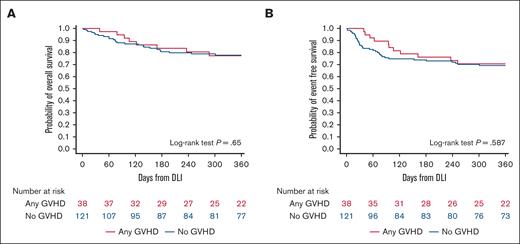

Survival after DLI administration

In recipients of HCTs with subsequent DLI, the OS and relapse-free survival (RFS) did not differ significantly between those with GVHD after DLI and those without (P = .65 for OS; P = .59 for RFS; Figure 4). HCTs performed in recent years, that is, in 2010-2015 (HR, 0.29; 95% CI, 0.13-0.65; P = .003) or 2016-2021 (HR, 0.17; 95% CI, 0.06-0.49; P = .001), for a primary diagnosis of nonmalignant disease (HR, 0.14; 95% CI, 0.03-0.78; P = .02), and with an MSD (HR, 0.21; 95% CI, 0.05-0.84; P = .03) were associated with better OS. Age at the time of transplant was associated with lower survival after DLI, with each additional year being associated with an increased risk of lower survival (HR, 1.08; 95% CI, 1.01-1.15; P = .03). Similarly, HCTs performed in 2010-2015 (HR, 0.42; 95% CI, 0.21-0.81; P = .01) or 2016-2021 (HR, 0.24; 95% CI, 0.10-0.58; P = .002), for a primary diagnosis of nonmalignant disease (HR, 0.08; 95% CI, 0.02-0.36; P = .001), and with subsequent post-DLI GVHD (HR, 0.49; 95% CI, 0.24-0.98; P = .05) were associated with better EFS after DLI. Sex mismatch between the donor and recipient did not affect the OS (P = .89) and RFS (P = .99) after DLI administration (supplemental Table 5).

Development of GVHD does not influence OS or EFS. Kaplan-Meier curves illustrating OS (A) and (B) EFS (B) for HCT recipients who developed GVHD or did not develop GVHD. P = .65 for OS, P = .59 for EFS (log-rank test).

Development of GVHD does not influence OS or EFS. Kaplan-Meier curves illustrating OS (A) and (B) EFS (B) for HCT recipients who developed GVHD or did not develop GVHD. P = .65 for OS, P = .59 for EFS (log-rank test).

Discussion

This study has demonstrated the relative safety and efficacy of DLI after HCT in patients with mixed donor chimerism or disease relapse. The risk of developing GVHD after DLI appears substantial, with reported rates being between 20% and 60% for aGVHD and between 5% and 66% for cGVHD.15-19 In our experience, the incidence of GVHD among HCT recipients after DLI was relatively moderate (31.4% for aGVHD, 12.6% for cGVHD). This incidence is probably secondary to the graded approach to DLI and the close monitoring of chimerism used at our institution, as described and published previously by our group, and others.12,17,18 Additionally, the incidence of GVHD after DLI was similar to that for HCTs performed without subsequent DLI (P = .06 for aGVHD; P = .08 for cGVHD) and the mortality rate was comparable for HCTs performed with and without subsequent DLI (P > .99). Furthermore, the OS and EFS of patients who developed GVHD after DLI were not worse than those for patients who did not develop GVHD after DLI (P = .65 for OS; P = .59 for EFS), demonstrating the relative safety of DLI in our cohort.

The impact of the timing of DLI on the eventual development of GVHD in HCT recipients has been debated. Previously, investigators found no difference in the rates of aGVHD and cGVHD in 81 adult patients who received their first DLI earlier or later than 180 days after their HCT.20 Likewise, others found that the duration of the interval between HCT and DLI was not associated with complications from DLI (ie, GVHD and/or bone marrow aplasia) in children who received MSD or MUD transplants (n = 51).21 In contrast, 1 study found a correlation between the duration of said interval and the development of GVHD in pediatric patients (n = 35) who received DLI for mixed chimerism from an MSD or an MUD/1-antigen–mismatched related donor; the median time to first DLI was 100 days for patients with GVHD vs 123 days for patients without GVHD (P = .013). Additionally, patients who received DLI after 7.5 months had a significantly lower risk of GVHD than those who received DLI sooner (6% vs 39%), suggesting that earlier administration of DLI is associated with a higher risk of GVHD.19 These previous studies lacked the data granularity that we achieved in our analysis by treating the unit of time as a continuous variable. We found that the hazard of aGVHD decreased by 2% for every additional day between the HCT and the first DLI. Furthermore, in our landmark analysis, administering DLI >100 days after HCT was associated with the lowest risk of aGVHD development in this pediatric cohort.

The ideal and safe dose of DLI has also been a topic of discussion. Bar et al previously showed that initial DLI CD3+ cell doses >1 × 107/kg were associated with an increased risk of GVHD in patients receiving MSD, MUD, or mismatched donor transplants (P = .03), with no comparable increase in OS or decrease in relapse incidence.22 Likewise, Hou et al showed that in pediatric patients receiving MSD or MUD transplants, a CD3+ dose >5 × 107/kg was associated with higher rates of cGVHD (P = .002) and lower OS (P = .089) than in patients who received a lower dose.23 However, for the HCTs with subsequent DLI in our study, the CD3+ cell dose was not associated with an increased risk of GVHD. Similarly, the use of mismatched donors or an increasing number of DLIs were not associated with an increased risk of GVHD in our study, in contrast to previous studies.21,24,25 As discussed earlier, this may have been secondary to the close monitoring of donor chimerism and the conservative DLI administration schema adopted at our institution.

In our study, the incidence of relapse among patients receiving HCTs with DLI was significantly higher than among those receiving HCTs without subsequent DLI. This is most likely because of the confounding effect whereby patients receiving DLI were probably being treated for positive MRD or mixed chimerism, both of which are associated with an increased risk of relapse. The overall response rates in our study after DLI were 45.2%, 33.3%, and 43.1% for mixed chimerism after MSD, MUD, and HAPLO HCT, respectively, and 50%, 0%, and 57.1%, respectively, for detectable MRD, which are similar to previously reported rates in the pediatric population.21,25 Although previous studies showed that patients who responded to DLI had better OS, we observed no OS advantage in this cohort.12

Response to DLI is influenced by the degree of MRD and tumor burden.26-28 However, this could not be evaluated in our study because of the low number of patients being treated for molecular relapse/MRD. In previous studies in adults, DLIs were reported to be more effective against myeloid malignancies.29 Although few pediatric studies have compared the efficacy of DLI in patients with myeloid and lymphoid malignancies, Liberio et al showed that pediatric patients in lymphoid disease groups who received DLI after a MSD, MUD, or HAPLO transplant experienced better 5-year survival than those in myeloid malignancy groups (71% vs 22%).30 In our study, response to DLI was superior in patients with lymphoid or myeloid malignancies, as compared with nonmalignant diseases. This finding may be partially related to the more aggressive approach to treating MRD and mixed chimerism that has been adopted for malignant disorders, as compared with nonmalignant disorders, for which mixed chimerism may be acceptable.

In 1 study of patients who had received HCTs from mismatched unrelated donors or fully matched donors, the former group had a higher response rate to DLI (78% vs 57%).25 Other researchers showed that children with nonmalignant diseases who responded to DLI for mixed chimerism had received DLI later after HCT when compared with nonresponders (279 vs 149 days) and that the effectiveness of DLI correlated with the total dose of CD3+ cells administered.21,31 In our study, none of these factors (donor source, initial CD3+ cell dose, or duration of the interval between HCT and DLI) were associated with the response rate. Although a longer interval between the HCT and DLI did not improve the response, a better risk profile arising from the lower incidence of GVHD could improve OS in patients receiving DLI after a longer interval after HCT.

DLI has occasionally been used to prevent recurrent infections in patients with delayed immune recovery, despite the limited data available.32 We observed a significantly lower incidence of death secondary to infections in recipients of HCTs with subsequent DLI as compared with recipients of HCTs without DLI (6.7% vs 20.9%, P = .001), indicating a potential added benefit of DLI after HCT.

As a retrospective single-center analysis, our study has some limitations. MRD data were not uniformly available for all patients, limiting our ability to evaluate the response to DLI for molecular relapse. The study also included patients with heterogeneous diagnoses with varying treatments before DLI, which was adjusted for in the statistical analysis. Additionally, the study was not designed to evaluate the role of other posttransplant management strategies such as maintenance chemotherapy, which may have contributed to the observed response. Similarly, donor characteristics such as age recently shown to potentially affect survival after DLI, were not evaluated.33 Furthermore, the exclusion of patients with active GVHD from the analysis of the efficacy and safety of DLI could have led to immortal time bias.

In conclusion, risk-adapted DLI infusion is associated with a low risk of GVHD and may be safely administered to children and young adults after HCT. The risk of GVHD is higher when DLI is administered closer to HCT and progressively decreases as the time from HCT increases, with the risk being minimal when DLI is administered after 100 days after HCT. With an encouraging response rate and a low risk profile, DLI may be considered a viable strategy for patients with developing mixed chimerism, impending graft failure, or low-level MRD.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Keith A. Laycock for scientific editing of the manuscript, as well as the technical staff in the Molecular Pathology laboratory, and the clinical pathologists for interpreting the chimerism results.

This study was supported by the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant P30CA021765 and by the American Lebanese Syrian Associated Charities.

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Authorship

Contribution: A. Sharma and S.S. initiated and designed the research; D.K. collected the data; Y.S., L.T., A. Sharma, and S.S. analyzed the data; S.S. made the figures and wrote the manuscript; A. Sharma directed and supervised the research; A.Q., A. Suliman, A.C.T., E.O., E.M., R.M., R.E., S.V.B., S.N., C.C.Z., M.P.V., P.A., S.G., and B.M.T. provided clinical care to the patients included in this study and reviewed the data analysis and its interpretation; and all authors reviewed the manuscript critically and provided input for the final draft.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: A.S. has received consultant fees from Spotlight Therapeutics, Medexus Inc, Vertex Pharmaceuticals, Sangamo Therapeutics, and Editas Medicine; serves as a medical monitor for a Resource for Clinical Investigation in Blood and Marrow Transplantation clinical trial for which he receives financial compensation; has received research funding from CRISPR Therapeutics and honoraria from Vindico Medical Education; and serves as principal investigator at the St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital site for clinical trials of genome editing for sickle cell disease sponsored by Vertex Pharmaceuticals/CRISPR Therapeutics (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT03745287), Novartis Pharmaceuticals (NCT04443907), and Beam Therapeutics (NCT05456880); the industry sponsors provide funding for the clinical trials, which includes salary support paid to the investigator’s institution, and A.S. has no direct financial interest in these therapies, these conflicts are managed through the compliance office at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital in accordance with their conflict-of-interest policy. S.G. is a coinventor on patent applications in the fields of cell or gene therapy for cancer; is a member of the scientific advisory board of Be Biopharma and CARGO Therapeutics; and is a member of the data and safety monitoring board of Immatics and has received honoraria from TESSA Therapeutics within the last year. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

The current affiliation for E.M. is Merck, Boston, MA.

Correspondence: Akshay Sharma, Department of Bone Marrow Transplantation and Cellular Therapy, St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, 262 Danny Thomas Pl, Memphis, TN 38105; email: akshay.sharma@stjude.org.

References

Author notes

The original data set will be shared for academic purposes and is available from the corresponding author, Akshay Sharma (akshay.sharma@stjude.org), on request.

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.