Abstract

For the past ten years, there has been a dynamic development of new therapeutic compounds and prognostic parameters for chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL). Hematologists and oncologists are challenged to use these new possibilities for an optimized, risk- and fitness-adapted treatment strategy, with the goal of achieving long-term remissions and preserving a good quality of life. This review is intended to summarize the current knowledge on first-line treatment of CLL.

The last ten years have seen a dynamic development of new agents for the treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL). Fludarabine and a monoclonal antibody, alemtuzumab, have been approved by the European and American regulatory agencies. Additional monoclonal antibodies (anti-CD20, rituximab; anti-CD23; anti-MHC II) as well as many other drugs (flavopiridol, bendamustine) are currently being tested in clinical trials. In addition, the increased experience with autologous and allogeneic progenitor cell transplantation allows to offer these intensified treatment modalities to physically fit patients at very high risk of relapse or at the time of relapse. However, the optimal combination and treatment sequence of these different novel treatment modalities remain unclear.

Similarly, rapid progress has been achieved with regard to new diagnostic tests to identify prognostic subgroups in CLL, and to assess their response to therapy. This review attempts to summarize the recent improvements in the first-line treatment of CLL.

Clinical Staging and Prognostic Markers

The survival period from the time of diagnosis of CLL varies between 2 and more than 10 years, depending on the stage. The staging systems of Rai et al1 and Binet et al2 are used to estimate prognosis. Both are based on the extent of lymphadenopathy, splenomegaly, and hepatomegaly on physical exam and on the degree of anemia and thrombocytopenia in peripheral cell counts. These simple studies are inexpensive and can be applied to every patient without technical equipment. Both staging systems describe three major prognostic subgroups. However, it has long been recognized that the above clinical staging systems are not sufficient to predict the individual prognosis, especially in the early stages of disease (Binet stage A, Rai stages 0–II) and in younger patients. Therefore, additional parameters have been identified allowing a more accurate prediction of the prognosis of CLL patients (Table 1 ).

While these parameters are potent in predicting the prognosis (survival, time to progression) of individual patients independent of the Binet or Rai stage, none of them has proven useful in predicting the need for chemotherapy in CLL patients. However, an assessment of these parameters is highly recommended within clinical trials.

Treatment Decision Is Based on Stage and Disease Progression

In 2005, any decision to treat should be guided by clinical staging, the presence of symptoms, and the disease activity. Evidence that current treatment can improve outcome is only available for patients with Rai III and IV or Binet B and C stages. Patients in earlier stages (Rai 0-II, Binet A) are generally not treated but monitored with a “watch and wait” strategy. In early stages, treatment is necessary only if symptoms associated with the disease occur (e.g., B symptoms, decreased performance status, or symptoms or complications from hepatomegaly, splenomegaly, and lymphadenopathy). High disease activity, often defined by a lymphocyte doubling time of less than 6 months or by rapidly growing lymph nodes, is also an indication to treat. In contrast, even in advanced disease (Rai III and IV or Binet C), the absence of disease progression (e.g., with a stable platelet count around 80,000/μl) may sometimes justify a “watch and wait” strategy.

Response Assessment Including Minimal Residual Disease

As with other malignancies, eradication of the disease is a desired endpoint of CLL treatment, especially in younger patients. New detection technologies have found that most patients who achieve a complete response as defined by the National Cancer Institute-sponsored working group (NCI-WG) guidelines3 typically have minimal residual disease (MRD). Critical in this assessment is a standardization of the techniques used to define MRD. The most sensitive techniques are 4-color flow cytometry and real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (PCR). Currently, the techniques for assessing MRD are undergoing further evaluation and standardization in an international effort led by A. Rawstron and P. Hillmen. These standardized techniques also need more testing in prospective clinical trials. Until this process is complete, it is premature to recommend the routine use of MRD testing in clinical practice. However, current and future clinical trials that aim toward achieving long-lasting complete remissions should include a test for MRD, because eradication of leukemia as evaluated with sensitive tests seems to have a strong prognostic impact.4–6

First-Line Treatment

Monotherapy with purine analogs

Three purine analogues are currently used in CLL: fludarabine, pentostatin, and cladribine. Fludarabine remains by far the best studied compound of the three in CLL. Fludarabine monotherapy produces superior overall response (OR) rates compared with other treatment regimens containing alkylating agents or corticosteroids.7–9 In three phase III studies in treatment-naïve CLL patients (Table 2 ), fludarabine induced more remissions and more complete remissions (CR) (7%–40%) than other conventional chemotherapies, such as CHOP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone), CAP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, prednisone), or chlorambucil.9–11 Despite the superior efficacy of fludarabine, only a trend for longer overall survival could be observed, and this trend was not statistically significant.9–11

Similarly, the comparison of cladribine monotherapy to chlorambucil plus prednisone in one phase III trial has yielded a higher CR rate of 47% versus 12%, respectively (Table 2 ). However, this difference did not result in a longer survival after cladribine first-line treatment (chlorambucil plus prednisone vs cladribine, 82% vs 78% at 2 years).

Combination chemotherapy with purine analogs

Fludarabine has been evaluated in a variety of combination regimens. The combination of fludarabine and another purine analog, cytarabine, appears to be less effective than fludarabine alone, while the combination of fludarabine with chlorambucil or prednisone increases hematological toxicity without improving the response rate compared with fludarabine alone (response rates 27%–79%).9,12

The most thoroughly studied combination chemotherapy for CLL is fludarabine plus cyclophosphamide (FC) (Table 2 ).12–15 In preliminary, non-comparative trials, the overall response rates did not appear to be better than with fludarabine alone, but the addition of cyclophosphamide appeared to improve the quality of the responses. This combination, with or without mitoxantrone, has achieved response rates of 64% to 100%, with CR rates of up to 50%.12 Variations on this regimen have shown that a slightly decreased cyclophosphamide dose improves the safety profile of the regimen without compromising efficacy, and that results were similar with concurrent or sequential administration of the two therapies.12 The addition of mitoxantrone to FC in 37 patients with relapsed/refractory CLL produced a high CR rate (50%), including 10 cases of MRD negativity, with a median duration of response of 19 months.6 All MRD-negative patients were alive at analysis; the median duration of response had not been reached in the CR patients compared to 25 months in non-CR patients. A phase II study of cladribine in combination with cyclophosphamide has also demonstrated activity in advanced CLL, but the results seemed inferior to those of FC.16

In a prospective trial of the German CLL study group (GCLLSG) comparing fludarabine versus FC, results for 375 patients showed superior response rate for the combination.17 The FC combination chemotherapy resulted in a significantly higher complete remission rate (16%) and overall response rate (94%) compared to fludarabine alone (5% and 83%; P = 0.004 and 0.001, respectively). The FC treatment also resulted in a longer median duration of response (48 vs 20 months; P = 0.001), and a longer event-free survival (49 vs 33 months; P = 0.001). So far, no difference in the median overall survival could be observed within a median observation period of 22 months. FC caused significantly more thrombocytopenia and neutropenia, but less anemia than fludarabine. FC did not increase the number of severe infections17 (Table 2 ).

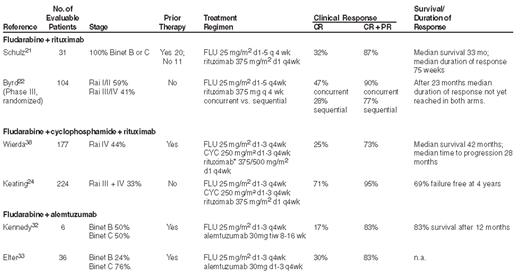

Rituximab-based chemo-immunotherapy

Rituximab, an anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody, has only recently provoked interest for the treatment of CLL. As a single agent rituximab is less active than in follicular lymphoma, unless very high doses are used.18,19 Somewhat surprisingly, combinations of rituximab with chemotherapy have proven to be very efficacious therapies for CLL. There is preclinical evidence for synergy between rituximab and fludarabine.20 The majority of rituximab combination studies in CLL have focused on combinations with fludarabine or fludarabine-based regimens (Table 3 ). A multicenter phase II study of the German CLL study group has evaluated the efficacy and safety of rituximab plus fludarabine in patients with previously treated or untreated CLL.21 Of 31 patients treated, 27 (87%) responded, with 10 patients (32%) achieving a complete response. Byrd and colleagues combined rituximab with fludarabine in either a sequential or concurrent regimen in a randomized study (CALGB 9712 protocol).22 Patients (n = 104) with previously untreated CLL received 6 cycles of fludarabine, with or without rituximab, followed by 4 once-weekly doses of rituximab. Overall and complete response rates were higher in the concurrent group (90% and 47% vs. 77% and 28%). More recently, in a retrospective analysis, all patients of the CALGB 9712 protocol treated with fludarabine and rituximab were compared with 178 patients from the previous CALGB 9011 trial, who received only fludarabine.23 The basic characteristics of patients were comparable, except for an 8-year longer observation time in the CALGB 9011 protocol. The patients receiving fludarabine and rituximab had a better progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) than patients receiving fludarabine alone. Two-year PFS probabilities were 67% versus 45% and 2-year OS probabilities were 93% versus 81%. Similarly, in a large phase II trial conducted at the MD Anderson Cancer Center on 224 patients with previously untreated CLL, rituximab plus fludarabine/cyclophosphamide (FC) achieved a response rate of 95%, with 71% complete responses.24 Median overall survival was not reached in patients treated with rituximab plus FC, and was significantly longer than in patients treated with FC alone in a historical comparison (Table 3 ).

Taken together, these results suggest that rituximab plus fludarabine-based therapies represent a significant advance in therapy for CLL. However, the analysis by Byrd and colleagues is retrospective and could be confounded by differences in supportive care or different prognostic subsets included in the two trials. Therefore, these findings need to be confirmed by prospective trials.

Alemtuzumab-based chemoimmunotherapy

Alemtuzumab is a recombinant, fully humanized, monoclonal antibody against the CD52 antigen. Monotherapy with alemtuzumab has produced response rates of 33% to 53%, with a median duration of response ranging from 8.7 to 15.4 months, in patients with advanced CLL who were previously treated with alkylating agents and had failed or relapsed after second-line fludarabine therapy.25–27 In addition, alemtuzumab has proven effective even in patients with poor prognostic factors, including high-risk genetic markers such as deletions of chromosome 11 or 17 and p53 mutations.28,29 If these results are confirmed in larger, prospective trials, alemtuzumab might be a rational choice for first-line treatment of patients with these poor prognostic factors.

Alemtuzumab consolidation therapy after fludarabine-based chemotherapy also improved the quality of responses, achieved molecular remissions in a substantial proportion of patients, and increased PFS compared with patients who had no further treatment.5,30,31 Results of a phase III trial by the GCLLSG showed improved PFS with alemtuzumab consolidation therapy compared to the observation arm (no progression vs 24.7 months, P = 0.036) when calculated from the start of fludarabine-based treatment.5 When PFS was calculated from the date of alemtuzumab administration, the same benefit was apparent, with no progression compared to 17.8 months (P = 0.036). O’Brien and colleagues reported an overall response rate of 53%, comprised of 9 of 23 (39%) at a 10-mg dose and 17 of 26 (65%) at a 30-mg dose (P = 0.066).31 Residual disease was cleared from the bone marrow in most patients, and 11 (38%) of the 29 patients with available data achieved a molecular remission. Median time to disease progression had not yet been reached for patients who achieved MRD negativity, compared to 15 months for patients who still had residual disease after alemtuzumab consolidation treatment.31 While the GCLLSG trial was halted early because of infectious adverse events, the study by O’Brien et al had no such issue, perhaps due to a longer time interval between induction therapy and consolidation with alemtuzumab (6 months versus 3 months in the GCLLSG study).

Perhaps the most potent regimen for CLL is the combination of the most effective single chemotherapeutic agent with the most effective monoclonal antibody—fludarabine plus alemtuzumab (Table 3 ). The synergistic activity of these two agents was initially suggested by the induction of responses, including one CR, in 5 of 6 patients who were refractory to each agent alone.32 The combination of fludarabine and alemtuzumab was investigated in a phase II trial enrolling patients with relapsed CLL (Table 3 ).33 Using a four-weekly dosing protocol, this combination has proven feasible, safe, and very effective. Among the 36 patients, the ORR was 83% (30/36 patients), which included 11 CRs (30%) and 19 PRs (53%); in addition, one patient achieved stable disease. Sixteen of 31 (53%) evaluated patients achieved MRD negativity in the peripheral blood by 3 months’ follow-up, and resolution of disease was observed in all disease sites, particularly in the blood, bone marrow and spleen. The fludarabine/alemtuzumab combination therapy was well tolerated. Infusion reactions (fever, chills, and skin reactions) occurred primarily during the first infusions of alemtuzumab, and were mild in the majority of patients. While 80% of patients were cytome-galovirus immunoglobulin G (CMV IgG)-positive before treatment, there were only two subclinical CMV reactivations. The primary grade 3/4 hematological events were transient, including leukocytopenia (44%) and thrombocytopenia (30%). Stable CD4+ T-cell counts (> 200/μl) were seen after 1 year. A phase III prospective randomized study evaluating the effectiveness of fludarabine and alemtuzumab combination in comparison with fludarabine alone is currently underway.

The combination of both monoclonal antibodies (alemtuzumab and rituximab) has been studied in patients with lymphoid malignancies, including those with refractory/relapsed CLL, producing an ORR of 52% (8% CR; 4% nodular PR [nPR]; 40% PR).34 A larger trial with longer follow-up is needed to confirm these preliminary results and determine the long-term efficacy of this combination.

Conclusion

1. Real progress: better diagnostic tools and more efficient therapies

In the last decade, impressive progress has been made both in the understanding of the pathogenesis and new diagnostic tests in CLL (see Table 1 ). In addition, novel combination therapies have led to an increased response rate and prolonged treatment-free survival, from complete remissions about 4% with chlorambucil to up to 70% with the novel chemoimmunotherapies using fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, rituximab, or alemtuzumab (Tables 2 and 3 ).

2. What is the value of new prognostic tests for the treatment indication?

Given the fact that most new prognostic markers now available for CLL patients have been tested only in studies with a small number of patients or in retrospective trials, and have often not been tested in comparison to all other available parameters, not enough information is currently available to use such new parameters in standard clinical practice. Future and ongoing clinical trials will need to determine whether patients at high risk for disease progression (i.e., with a number of unfavorable prognostic markers like the ones described above) actually benefit from early treatment intervention. Until we have learned more about the clinical relevance of these tests, the clinical staging systems and conventional clinical follow-up remain the backbone of the initial decision making with regard to the initiation of treatment and follow-up.

3. Which treatment combination should be used in first line?

With the potential of potent chemoimmunotherapy regimens described above, choosing the right treatment for a patient with CLL has become a task that requires skill and experience. There are at last three potentially relevant points to consider when selecting the optimal treatment for an individual patient:

The physical condition (fitness and comorbidity) of the patient, which is independent of calendar age.

The prognostic risk of the leukemia as determined by the factors mentioned above.

The Rai or Binet stage of the disease.

The second generation of clinical trials of the German CLL Study group proposes a strategy that incorporates these three factors (Figure 1; see Color Figures, page 551). Patients at early stage (CLL7 protocol of the French and German study groups) are not treated (and should also not be treated outside clinical trials), if there is no risk associated with the leukemia. With more than one of four unfavorable risk factors (unfavorable cytogenetics, unmutated IgVH, elevated serum thymidine kinase, short lymphocyte doubling time), patients are randomized to receive either immediate or delayed FCR treatment.

In patients at advanced stage (Figure 1; see Color Figures, page 551), there is general consensus to start treatment, as discussed above. In this situation, the patients need to be evaluated for their physical condition (or comorbidity) before any decision is made. For patients in good physical condition (“go go”) as defined by a normal creatinine clearance and a low score at the “cumulative illness rating scale” (CIRS),35 patients are included in the CLL8 protocol which randomizes between the FC and FCR regimen as first-line treatment. Patients with a somewhat impaired physical condition (“slow go”) as defined by an elevated CIRS score and a creatinine clearance < 70 mL/min are included in the CLL9 protocol, where a dose-reduced fludarabine regimen is given and patients are randomized to receive Darbepoetin alfa to improve the hemoglobin levels and treatment outcome. It should be emphasized that in this group of patients the former standard of CLL therapy, chlorambucil, remains very useful.

Regardless of the stage, patients with 17p– deletion or p53 mutations should probably receive an alemtuzumab-containing regimen as first-line treatment, because these patients respond poorly to fludarabine or fludarabine-cyclophosphamide.

Taken together, a fortunate wealth of new diagnostic and therapeutic options requires a more careful evaluation of the patient and the leukemia before making the decision of whether and how to treat. This evaluation includes both risk factors associated with the biology of the leukemia itself and the physical constitution of the individual patient.

4. Future directions

Given the rapid progress in CLL research, a rapid change in the management of CLL can be anticipated (Table 4 ). Genetic parameters will allow the physician to predict both prognosis and response to treatment more precisely. For example, alemtuzumab might be the treatment of choice in patients with a chromosomal aberration 17p– and/or p53 mutations.28,29 These patients do not benefit from fludarabine and alkylator monotherapies, and we will know soon whether they respond to combination chemoimmunotherapy.

In addition, genomic microarray analysis or the investigation of single nucleotide polymorphisms in patients prior to treatment will mostly likely add information and improve our ability to predict which patients will respond to which treatment.

As a consequence, treatment of CLL will become much more diverse and individualized. While some patients might benefit maximally even from the traditional monotherapy with alkylators or fludarabine, others will require a more sophisticated approach including chemoimmunotherapy induction therapy, followed by a maintenance treatment with antibodies or immune gene therapy using the transfer of the CD40 ligand gene into CLL cells.36 Maintenance or consolidation treatment will be monitored by sensitive techniques to eradicate minimal residual disease. Additional drugs (small molecules, antibodies) will be used in this future multi-modal therapeutic approach. Given the increasing efficacy of new chemoimmunotherapies, autologous stem cell transplantations will be used at reduced frequency.

While a detailed analysis of these future treatment options is beyond the scope of this review, this optimistic look into the future should influence the current management of some of our CLL patients: Because one can expect that better treatment options with less side effects are soon to come, the first-line approach in CLL today may present the task of “buying” some good time for the patient, instead of aiming for immediate, aggressive therapies such as allogeneic stem cell transplants, which might eventually cure some patients but also worsen the quality of life of many others.

Klinik I für Innere Medizin, Universität zu Köln, Germany

Acknowledgment: I wish to thank all members and participants of the German CLL Study Group for their continuing support and excellent cooperation. In particular, I wish to thank Dr. Barbara Eichhorst for critically reading this manuscript. This work is supported by the Deutsche Krebshilfe (German Cancer Aid), and the Kompetenznetz Maligne Lymphome (Competence Network Malignant Lymphoma) of the German Ministry for Education and Research (BMBF).