Abstract

Healthcare institutions in the United States must review blood transfusion practices and adverse outcomes in order to receive payments from the Centers for Medicare/Medicaid program, but it is not required for a specific committee to be assigned to oversee the review process. Regardless of the group or individuals responsible, the review process must include a program of quality assessment and performance improvement that is ongoing, hospital-wide, and data-driven, reflects the complexity of the hospital’s organization and services, and involves all hospital departments and services (including those contracted). To be most effective, the performance improvement activity should be prioritized around high-risk, high-volume activities and/or in problem-prone areas. Even if a hospital elects not to receive payments from Medicare, it must still comply with applicable sections of the Code of Federal Regulations pertaining to transfusion services such as the follow up of adverse outcomes of transfusion.

Overview

Regulatory agencies and accrediting organizations require healthcare institutions to review blood transfusion practices and adverse outcomes, but do not specifically require that an institution assign a committee to accomplish that function. The Code of Federal Regulations (CFR)1 requires a hospital to develop, implement, and maintain an effective, ongoing, hospital-wide, data-driven quality assessment and performance improvement (QA/PI) program that reflects the complexity of the hospital’s organization and services, involves all hospital departments and services (including those services furnished under contract or arrangement), focuses provider efforts to improve health outcomes, and prevents adverse events including medical errors. Failure to do so jeopardizes payments from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services program (CMS, formerly the Health Care Financing Administration). To be most effective, the performance improvement activity should be prioritized around high-risk, high-volume activities and/or in problem-prone areas. Blood transfusion is considered by many to be a high-risk, high-volume activity because in the United States an average of 38,000 units of red blood cells are transfused each day, and over 3.5 million patients receive a transfusion annually.2 Furthermore, adverse outcomes of transfusion such as transfusion-related acute lung injury (TRALI) and hemolytic reactions are not rare.3 Thus it is logical that a hospital’s transfusion practices should fall under the jurisdiction of a hospital QA/PI program.

Certification of a hospital’s compliance with federal regulations is based on either an on-site inspection by CMS or an inspection by a state agency or national accrediting organization that has been approved by CMS to perform such an inspection on behalf of CMS. The Joint Commission on the Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (JCAHO) is an example of a national accrediting agency that may inspect on behalf of CMS, and CMS may elect to “deem” a JCAHO-accredited institution as having met the Medicare and Medicaid certification requirements, without performing its own on-site CMS survey. Even if a hospital chooses not to receive payments from Medicare, it must still comply with applicable sections of the CFR, including 21CFR 211.100(a), 21 CFR 211.100(b), 21CFR 606.170(a), 21CFR 606.170(b), 21CFR 606.170(c), and 42 CFR 493.1103 pertaining to transfusion services, including the follow up of adverse transfusion reactions and other potential risks of transfusion.

The JCAHO has historically emphasized oversight of transfusion practice, and has required monitoring of blood utilization since 1961.4 In 1999, the JCAHO published a sentinel event alert entitled “Blood Transfusion Errors: Preventing Future Occurrences.”5 In the sentinel event alert the JCAHO cautioned that the processes involved in blood transfusion exhibit virtually all of the factors recognized to increase the risk of an adverse outcome and offered suggestions to redesign systems and processes to improve transfusion safety. In 2002, the JCAHO began to publish a series of National Patient Safety (NPS) Goals,6 including NPS Goal #1, which requires improvement in the accuracy of patient identification as it relates to blood transfusion. According to NPS Goal #1, each healthcare organization should: “Use at least two patient identifiers (neither to be the patient’s room number) whenever taking blood samples or administering medications or blood products.” The JCAHO’s NPS Goals also require health care organizations to improve effectiveness of clinical alarm systems as well as the safety of using infusion pumps. The JCAHO performance improvement standards call for collection of data regarding utilization of blood,7 requires medical staff take a leadership role in measurement, assessment, and improvement of clinical processes related to use of blood and blood components and requires that all confirmed transfusion reactions be analyzed.8 The assessment process must include peer review, the findings of which must be communicated to involve staff members and be a part of the process for renewal of clinical privileges.

The JCAHO is not alone in its activities to improve transfusion practice and to reduce the risk of adverse outcomes from transfusion via the accreditation process. The American Association of Blood Banks (AABB) calls for hospitals to conduct blood utilization review, as a part of an institution’s quality plan,9 as well as requiring that there be a peer-review program to monitor appropriateness of use of blood components.10 Specifically, AABB requires monitoring of blood utilization, which includes having a peer-review program that monitors and addresses transfusion practice for all categories of blood and components, and that the categories to be monitored include:

ordering practices

patient identification

sample collection and labeling

infectious and non-infectious adverse events

near-miss events

usage and discard

appropriateness of use

blood administration policies

the ability of services to meet patient needs

compliance with peer-review recommendations.

When problems with any of the above categories are discovered, process improvement through corrective and preventive action must take place and be documented. The AABB requires that there be a process for detection, evaluation, and reporting of suspected transfusion-related adverse events. When a transfusion fatality or other serious, unexpected adverse event occurs that is suspected to be related to an attribute of a donor or a unit, that the collecting facility must be notified immediately and in writing.11 The College of American Pathologists (CAP) laboratory accreditation program requires transfusion oversight, as mandated by its general standard on quality control and improvement, which states that the blood bank director must evaluate the appropriateness of any laboratory’s output in a multidisciplinary fashion.12 Moreover, the CAP accreditation check list for blood banks seeks documentation that “ . . . the transfusion service medical director actively participates in establishing criteria and in reviewing cases not meeting transfusion audit criteria.”13

While not specifically mentioning that a committee must oversee transfusion service activities or the resolution of adverse transfusion outcomes, many activities needing to be monitored for compliance with federal regulations and accreditation requirements lend themselves to oversight by a committee. Typically this function has been delegated to a dedicated “Blood Utilization Committee,” “Transfusion Committee” or combined “Tissue and Transfusion Committee.” Regardless of which structure is chosen, it should be reflected in the institution’s bylaws. By including the oversight structure in the bylaws, the governing body, medical staff, and administrative officials become legally accountable, which may encourage allocation of adequate resources for measuring, assessing, improving, and sustaining the hospital’s performance and reducing risk to transfused patients.

Model Organization for a Transfusion Services Committee

Regardless of the system used for oversight of transfusion practices, active participation by physicians, nurses, administrators and other interested individuals is required, because without a multidisciplinary approach, it is difficult to prevent adverse transfusion-related events or to take appropriate corrective actions should such events occur. The authors believe that the exact structure of a Transfusion Services Committee can be left to the discretion of the institution, so long as the following issues are addressed:14–16

Support for oversight of transfusion practices is secured from senior management at the level of the institutional owners, governing body, board of directors, or equivalent group.

Committee representation is from all major medical and surgical departments that order blood or blood conservation technologies (including surgery, anesthesia, medicine, neonatology, pediatric hematology, adult hematology, and cardiothoracic surgery).

Representation is included from nursing services, pharmacy, biomedical engineering, refrigeration, and other support services including the institution’s main blood supplier.

The committee chair is a physician who is knowledgeable in transfusion medicine. Although the chair does not need to be the transfusion service medical director, the transfusion service medical director should be a member of the committee.

Committee meetings are documented by minutes that are submitted to medical and executive leadership for their review and approval, and which are protected from inappropriate ‘discovery.’ For example, in California, medical staff committee minutes are protected under Evidence Code Section 1157 and Government Code Section 6254.17,18 Each committee member should sign a confidentiality agreement.

When liability issues are discussed, guests and other individuals who do not have a need to know details are excused.

Appropriate policies define institutional transfusion practices. Physicians and nursing services must be aware of these policies and abide by them. Examples of policies include the following (list is not meant to be exhaustive):

⇒ Consent for transfusion

⇒ Refusal of transfusion

⇒ Pretransfusion testing orders (Use of “Type and Hold Clot,” Type and Screen, Type and Crossmatch)

⇒ Surgical blood order schedules

⇒ Ordering practices including when to initiate transfusion, what product to administer, rate of administration, and use of terms such as STAT versus NOW versus ASAP versus TODAY

⇒ Medical indications for blood and blood product transfusion

⇒ Clinical alternatives to blood transfusion

⇒ Patient identification (both at time of specimen collection and at time of blood product transfusion)

⇒ Blood product administration practices (e.g., “hanging” the blood)

⇒ Management of massive transfusion

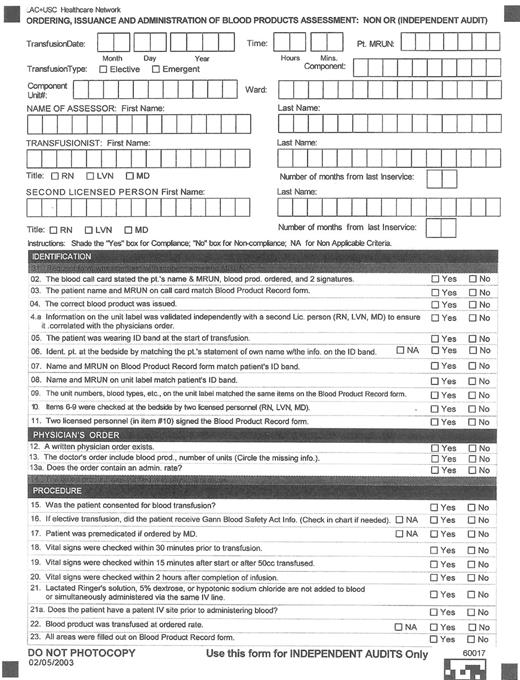

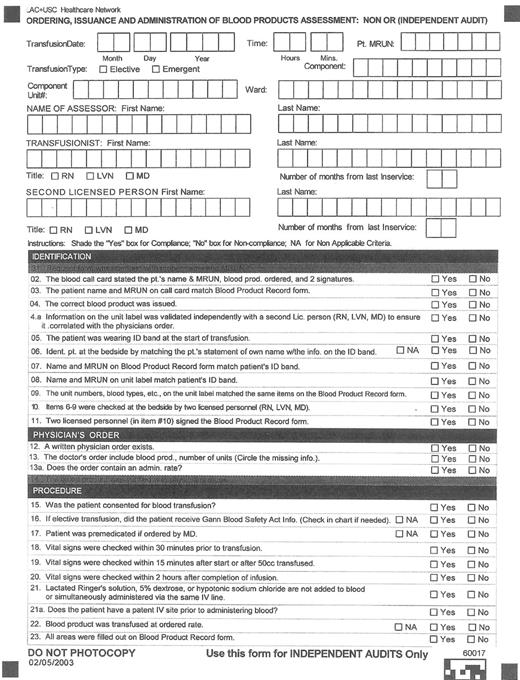

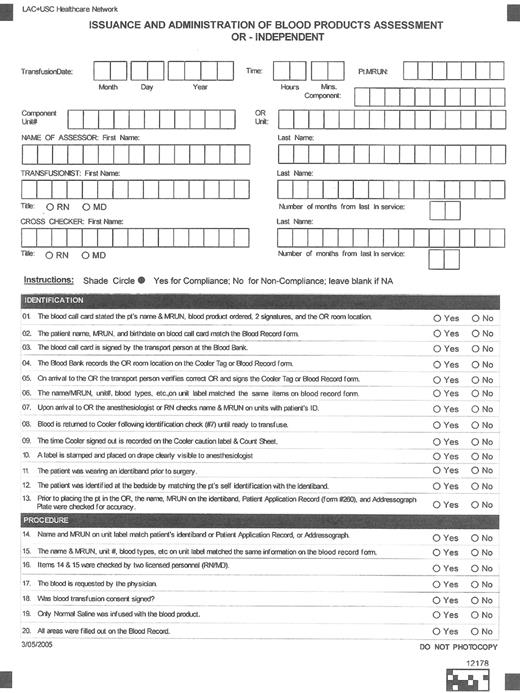

Audits for compliance with local policies and procedures assess the entire transfusion process, including transfusion practices within the operating room.19,20 See Figure 1 for examples of audit tools that can be used to assess transfusion practices, including in the OR. Such audits provide a mechanism to document hospital compliance with the NPS Goal #1.

Adverse events, incidents and errors are investigated including:

⇒ Facilitate root cause analysis for sentinel events

⇒ Identify the need for further education or amendments to existing procedures

⇒ Facilitate reporting of events to appropriate departments within the hospital and/or to local, state and federal agencies as required by policy and/or statute. For example, all transfusion services (whether licensed by the US Food and Drug Administration [FDA], FDA registered, or unregistered with FDA) must report to the FDA biological product deviations (BPD) that may affect the safety, purity, or potency of a distributed product in accordance with 21 CFR, Part 600.14 or 606.171,21 and fatal reactions in accordance with 21 CFR 606.170(b).22

Product losses are monitored to show products expired under direct control of the laboratory (inside laboratory loss) versus outside the laboratory due to improper ordering or handling (outside laboratory loss).

Operational effectiveness of the laboratory service is reviewed, e.g., response times for emergency requests.

Results of external proficiency testing and accreditation surveys are reviewed.

Quality indicators that address adverse patient events, processes and quality of care, hospital service and operations, and effectiveness and safety of services are monitored (such as the functioning of blood warmers),23 measured, tracked, analyzed and presented in a standardized graphic format, (e.g., bar graph or line graph format so that trends are easy to see). See Table 1 for a list of potential quality indicators.

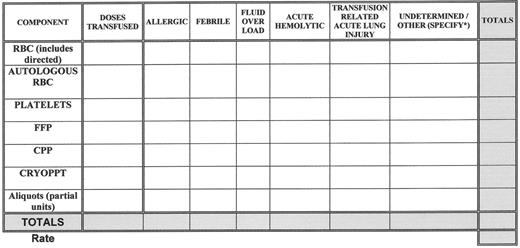

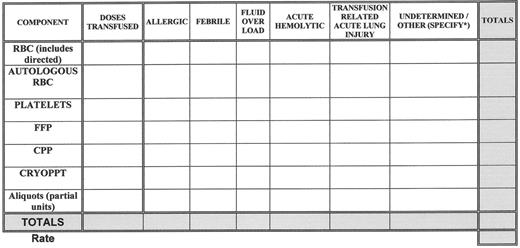

Medical errors (with or without an adverse outcome) and adverse patient events related to transfusion are tracked, analyzed for causes, categorized and reviewed for sentinel events, (e.g., acute fatal hemolytic transfusion reactions or other transfusion related fatality). See Figure 2 for a sample template that can be used to track and trend transfusion reactions. Whenever corrective actions are implemented there is measurement of the effect of those actions and tracking of performance to ensure that the improvements are sustained.

Fatal and other reactions reported to FDA and/or to JCAHO are discussed.

Product contamination is reported to the blood product supplier and other local, state and/or federal agencies as required by policy and/or statute.

There is a mechanism for involving the medical staff in performance improvement activity including feedback and learning throughout the hospital.

There is an integrated plan for the management of blood shortages, including planning for the management of patients based on predetermined categories (e.g., patients in need of immediate resuscitation, patients in need of urgent surgical support, non-surgical patients who are anemic, scheduled but non-emergent surgical patients).

There is an ongoing process of quality assessment and performance improvement that utilizes one or more of the following tools and models that can facilitate identifying transfusion-related problems, addressing underlying causes, designing and implementing corrective action activities, determining the degree of success of an intervention, and detecting new problems and opportunities for improvement (see Table 2 for details):

There is a blood usage review program to ensure all services and all major products are included in the review process.

There are measures that define the effectiveness of the committee.

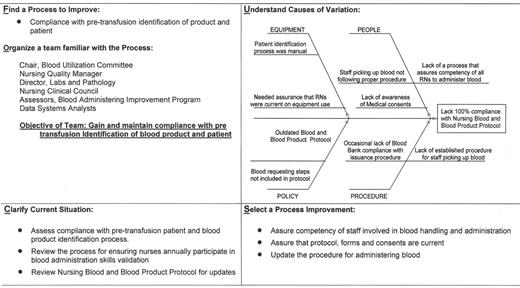

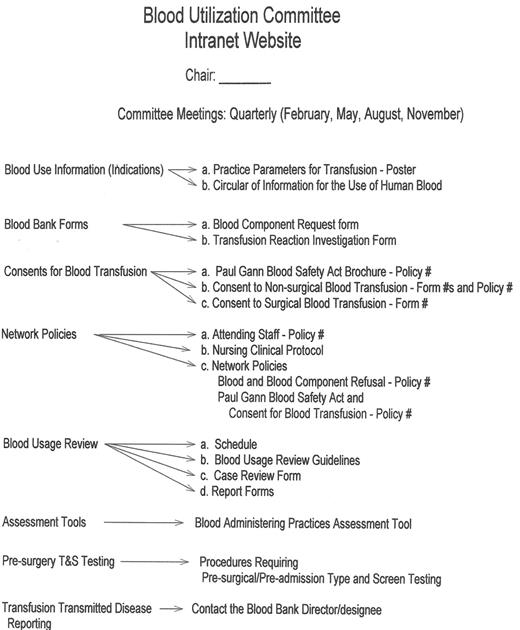

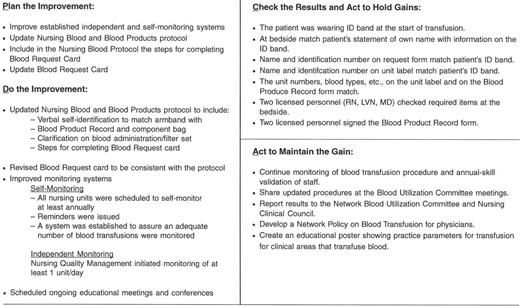

An example of a “Transfusion Committee” that meets most of the above criteria has been reported in detail elsewhere.28 That committee employs a multidisciplinary approach, including the use of FOCUS PDCA and root cause analysis to identify corrective actions and effect necessary changes (improvements). An example of a FOCUS PDCA ‘storyboard’ (Figure 3 ) demonstrates the steps that can be taken following an error in blood product administration. A root cause analysis helps to identify the primary and contributing factors (causes) of the error (as shown in the fishbone display in Figure 3 ). The FOCUS PDCA process also helps to organize the change process. Timely communication of meeting minutes and QA/PI activities should be disseminated to physicians and nursing staff who can act on the corrective actions. One such mechanism for information dissemination is to employ a website, such as the one that has been created at the authors’ institutional Intranet. (Figure 4 ) With the recent emphasis on patient safety by the JCAHO, the need is compelling for a medical staff committee that is accountable to senior management and concerned with the appropriateness and safety of blood transfusion practice.

Assessment tool for the transfusion process.*

* This assessment tool is designed for use outside of the operating rooms.

Assessment tool for the transfusion process.*

* This assessment tool is designed for use outside of the operating rooms.

Blood Administration Process Improvement Focus—PDCA Model Storyboard.

Keck School of Medicine of the University of Southern California, Los Angeles CA