Abstract

Paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (PNH) is an uncommon intravascular hemolytic anemia that results from the clonal expansion of hematopoietic stem cells harboring somatic mutations in an X-linked gene, termed PIG-A. PIG-A mutations block glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI) anchor biosynthesis, resulting in a deficiency or absence of all GPI-anchored proteins on the cell surface. CD55 and CD59 are GPI-anchored complement regulatory proteins. Their absence on PNH red cells is responsible for the complement-mediated intravascular hemolysis. Intravascular hemolysis leads to release of free hemoglobin, which contributes to many of the clinical manifestations of PNH including fatigue, pain, esophageal spasm, erectile dysfunction and possibly thrombosis. Interestingly, rare PIG-A mutations can be found in virtually all healthy control subjects, leading to speculation that PIG-A mutations in hematopoietic stem cells are common benign events. However, negative selection of PIG-A mutant colony-forming cells with proaerolysin, a toxin that targets GPI-anchored proteins, reveals that most of these mutations are not derived from stem cells. Recently, a humanized monoclonal antibody directed against the terminal complement protein C5 has been shown to reduce hemolysis and greatly improve symptoms and quality of life for PNH patients.

Paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (PNH) is a rare clonal hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) disorder that leads to chronic hemolysis, a propensity for venous thrombosis, and bone marrow suppression.1–4 PNH can arise de novo or arise from acquired aplastic anemia.5 The PNH stem cell and all of its progeny have a deficiency of an entire class of cell surface proteins, known as glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored proteins (GPI-AP). GPI-APs serve many purposes and may function as enzymes, receptors, complement regulators and adhesion molecules. The GPI-AP defect in PNH results from a mutation in an X-linked gene known as PIG-A (phosphatidylinositol glycan class A)6; the product of this gene is necessary for the first step in the biosynthesis of glycosylphosphatidylinositol, a glycolipid moiety that tethers GPI-AP to the plasma membrane.7 All PNH patients examined to date have been shown to harbor clonal PIG-A gene mutations. Rare PIG-A mutations have also been found in the peripheral blood and bone marrow cells from virtually all healthy controls, suggesting that PIG-A mutations are necessary, but insufficient to cause PNH.8–11 More recent data demonstrate that most of the PIG-A mutations found in healthy controls arise in colony-forming cells rather than HSCs. Since colony-forming cells have no self-renewal capacity, the PIG-A mutations found in healthy controls may have little or no relevance to the pathophysiology of PNH.11 Until recently, there was no effective therapy for PNH other than allogeneic bone marrow transplantation; however, the development of eculizumab, a monoclonal antibody that inhibits the terminal stage of the complement cascade, appears to be highly effective for controlling hemolysis and many of the symptoms of PNH.

GPI-anchor Biosynthesis

Covalent linkage to GPI is an important means of anchoring many cell surface glycoproteins to the cell membrane. There are more than a dozen different GPI-AP on hematopoietic cells alone. GPI is synthesized in the endoplasmic reticulum and transferred en bloc to the carboxyl terminus of a protein that has a GPI-attachment signal peptide. Biosynthesis of GPI anchors involves at least 10 reactions and more than 20 different genes.

The common core structure of GPI consists of a molecule of phosphatidylinositol and a glycan core that contains glucosamine, three mannoses and an ethanolamine phosphate (Figure 1; see Color Figures page 516). The first step in GPI anchor biosynthesis is the transfer of N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc) from uridine 5′-diphospho-N-acetylglucosamine (UDP-GlcNAc) to phosphatidylinositol (PI) to yield GlcNAc-PI. This step is catalyzed by GlcNAc:PI α 1–6 GlcNAc transferase, an enzyme whose subunits are encoded by 7 different genes: PIG-A,6PIG-C,12PIG-H,13GPI1,14PIG-Y,15PIG-P and DPM2.16 The second step is the de-N-acetylation of GlcNAC-PI to GlcN-PI.17 Later, three mannoses from dolichol-phosphate-mannose and an ethanolamine phosphate from phosphatidylethanolamine are added sequentially. The core is modified with side groups during or after synthesis. The last step in GPI anchor processing is the attachment to the newly synthesized proprotein via a transamidase-like reaction (involving at least 5 gene products), during which a C-terminal GPI attachment signal is released.18 The GPI-AP then transit the secretory pathway to reach their final destination at the plasma membrane, where they reside in 50- to 350-nm microdomains known as lipid rafts.

Intravascular Hemolysis and Nitric Oxide

Many of the clinical manifestations of PNH are readily explained by hemoglobin-mediated nitric oxide scavenging.19 PNH erythrocytes are more vulnerable to complement-mediated lysis because of a reduction, or complete absence, of membrane inhibitor of reactive lysis (CD59) and decay accelerating factor (CD55), both of which are GPI-anchored. Failure of complement regulation on the PNH erythrocyte membrane renders these cells vulnerable to complement-mediated lysis, resulting in the release of large amounts of free hemoglobin into the plasma. Free plasma hemoglobin leads to increased consumption of nitric oxide, resulting in manifestations that include fatigue, abdominal pain, esophageal spasm, erectile dysfunction, and possibly thrombosis. Indeed, hemoglobinuria, thrombosis, erectile dysfunction and esophageal spasm are more common in patients with large PNH populations (> 60% of granulocytes) than in patients with relatively small PNH populations.2

PIG-A Mutations

Despite the large number of genes required for GPI anchor biosynthesis, GPI-AP deficiency in PNH patients is a direct consequence of mutations involving PIG-A.5–7,20–22 Most PIG-A mutations are small insertions or deletions that result in a frameshift or early termination of transcription. More than 100 mutations spanning the PIG-A coding region have been described with very few repeated mutations.23PIG-A is located on chromosome Xp22.1; all other genes involved in GPI biosynthesis reside on autosomes. Inactivating mutations in these genes would have to occur on both alleles to produce the PNH phenotype, a statistically unlikely event. Thus, a single inactivating mutation in the X-linked PIG-A gene will generate a PNH phenotype since males have only one X chromosome and in females one X chromosome is randomly inactivated in somatic cells through lyonization. Similar to the myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS), chronic myelocytic leukemia, and poly-cythemia vera, PNH is typically a monoclonal HSC disorder. Direct evidence of clonality was established through sequence analysis of the PIG-A gene in PNH patients; matching PIG-A mutations can be found in all lineages, demonstrating that the “hit” in PNH involves a multipotent HSC.

Diagnosis

Complement-based assays such as the sucrose hemolysis test and the Ham test were used to diagnose PNH before 1990. These assays are relatively insensitive and non-specific, especially in patients requiring red cell transfusions. Furthermore, these assays are not quantitative. Monoclonal antibodies to GPI-anchored proteins (e.g., anti-CD59 and anti-CD55) began to replace the sucrose hemolysis and Ham test in the early 1990s.24 Later, GPI-anchored proteins were shown to be receptors for proaerolysin, a bacterial channel-forming toxin derived from Aeromonas hydrophila. Since PNH cells are deficient in GPI-anchored proteins they are resistant to the toxin.25 Proaerolysin can be used to select for small populations of PNH cells. In addition, a fluoresceinated proaerolysin variant (FLAER) that binds to the GPI anchor without forming channels can be used in conjunction with flow cytometry to diagnose PNH.26 When compared directly, FLAER was shown to be more sensitive and specific for the diagnosis of PNH and appears to give a better estimate of the size of the PNH clone.

PIG-A Mutations in Aplastic Anemia and MDS

Small to moderate PNH clones are found in up to 70% of patients with acquired aplastic anemia, demonstrating a pathophysiologic link between these disorders.27,28 Typically, less than 20% GPI-AP–deficient granulocytes are detected in aplastic anemia patients at diagnosis, but occasional patients may have larger clones. DNA sequencing of the GPI-AP–deficient cells from aplastic anemia patients reveals clonal PIG-A gene mutations.5 Moreover, many of these patients exhibit expansion of the PIG-A mutant clone and progress to clinical PNH. While it was once thought that PNH evolving from aplastic anemia is more benign than classical PNH, this observation is likely a consequence of lead time bias, since many of these patients eventually develop classical PNH symptoms after the PIG-A mutant clone expands.

GPI-AP–deficient cells have also been reported in patients with MDS,28,29 but sequencing of the PIG-A gene to establish clonality has not been performed in most of these studies. MDS patients reported to have small PNH populations tend to be classified as refractory anemia and often have the following characteristics: a hypocellular marrow, HLA-DR15 positivity, normal cytogenetics, moderate to severe thrombocytopenia and a high likelihood of response to immunosuppressive therapy.28,30 Thus, it is possible that many of these patients have moderate aplastic anemia rather than MDS. Distinguishing hypoplastic MDS from aplastic anemia is often difficult; however, quantitative analysis of bone marrow CD34+ cells is useful for discriminating between these two entities.31

PIG-A Mutations in Healthy Controls

PNH is an uncommon disease, with only 2–5 new cases per million US inhabitants annually; however, PIG-A mutations can be found in the blood from virtually all healthy controls.8 Araten and coworkers8 used flow cytometric analysis of blood from 9 healthy controls and found an average of 22 GPI-AP–deficient granulocytes per 106 cells, yet none of these subjects developed PNH. GPI-AP–deficient lymphocytes have also been detected in patients with lymphoid malignancies or rheumatoid arthritis after treatment with CAMPATH-1H, a monoclonal antibody that recognizes CD52, a GPI-AP expressed on monocytes, B cells and T cells.9,32–34 None of these patients developed PNH; furthermore, when the CAMPATH was discontinued, the GPI-AP–deficient cells regressed. Moreover, Ware and colleagues used proaerolysin to negatively select GPI-AP T cell clones from healthy controls and demonstrated that GPI-AP deficient T cell clones exist at a frequency of 17.8 ± 13.8 per 106 mononuclear cells.10

How can such a common mutation, PIG-A, be so specific for PNH, yet so rarely result in disease? One hypothesis is that PIG-A mutations are necessary, but insufficient to cause the disease. A two “hit” model for developing PNH proposes that PIG-A mutations are common benign events in HSCs and that these cells only undergo clonal expansion in the setting of immune selection that targets normal stem cells but spares PNH stem cells. While conceptually appealing, the mechanism of clonal expansion in PNH is undoubtedly more complex. PNH is usually a monoclonal disease and it seems unlikely that we all harbor a single PIG-A mutant HSC. If this were the case, virtually all patients with aplastic anemia would evolve to PNH. While some studies have found more than one PIG-A mutant clone in PNH patients (1 study found as many as 4 distinct somatic mutations in 1 patient), analysis of colony forming cells (CFC) from PNH patients harboring more than 1 PIG-A mutation usually reveals a single dominant clone.35,36 Thus, why would one PIG-A mutant clone preferentially expand over another? Furthermore, MDS evolves from aplastic anemia with a similar frequency as PNH, and MDS cells have no defect in GPI anchor biosynthesis.

Recently, Hu et al isolated CD34+ progenitor cells from 4 PNH patients and 27 healthy controls to determine whether HSC from healthy controls harbor PIG-A mutations.11 The frequency of PIG-A mutant progenitors was determined by assaying for CFC in methylcellulose containing toxic doses of proaerolysin. The frequency of proaerolysin-resistant CFC was 1 in 65,000 from healthy controls. DNA was extracted from individual proaerolysin-resistant CFC, and the PIG-A gene was sequenced to determine clonality. Proaerolysin-resistant CFC from PNH patients exhibited clonal PIG-A mutations that involved all lineages (myeloid, erythroid and lymphoid). In contrast, PIG-A mutations from healthy controls were polyclonal (i.e., did not match each other) and did not involve lymphocytes. One healthy control had 15 different PIG-A mutations isolated from CFC. In contrast to PNH, PIG-A mutations that arise in healthy controls are polyclonal and occur in cells as early as CFU-GEMM, but not earlier, suggesting that these mutations are probably a function of normal differentiation and have little relevance to human disease. Unlike HSC, CFC have no self-renewal capacity; hence, mutations at this level will not be propagated. These findings are also clinically important when using flow cytometry to identify small PNH-like populations in the blood. Healthy controls normally have up to 0.005% non-clonal PNH-like cells; thus, specimens with less than 0.01% are unlikely to be clonal or clinically relevant.

Treatment

Before initiating treatment for PNH patients it is useful to stratify them into classical PNH or hypoplastic PNH. This can usually be accomplished by obtaining a complete blood count, reticulocyte count, LDH determination, peripheral blood flow cytometry and a bone marrow examination. Patients with classical PNH tend to have mild to moderate cytopenias, a normocellular to hypercellular bone marrow, an elevated reticulocyte count, a markedly elevated LDH level and > 60% GPI-AP–deficient granulocytes. Hypoplastic PNH patients present with manifestations of bone marrow failure. In fact, more than 50% of patients with aplastic anemia harbor small PNH clones. These patients typically present with moderate to severe pancytopenia, a hypocellular bone marrow, a decreased corrected reticulocyte count, a normal or mildly elevated LDH level and a small PNH granulocyte population (< 20%).

Hypoplastic PNH

Since bone marrow failure is the major source of morbidity and mortality for patients with hypoplastic PNH, therapy should be directed toward improving the cytopenias. In patients with PNH clones who meet criteria for severe aplastic anemia, appropriate therapeutic options include allogeneic bone marrow transplantation,37 high-dose cyclophosphamide,38 or antithymocyte globulin and cyclosporine.39 If the patient’s cytopenias do not fulfill criteria for severe aplastic anemia, watchful waiting or immunosuppressive therapy is appropriate.

Classical PNH

Patients with classical PNH are at increased risk for thrombosis and other complications of intravascular hemolysis. Until recently, allogeneic bone marrow transplantation was the only effective therapy for these patients; however, the development of eculizumab now offers them great hope. Alternate-day prednisone therapy is occasionally helpful in ameliorating hemolysis in PNH, but most patients show little or no response to this treatment.

Eculizumab

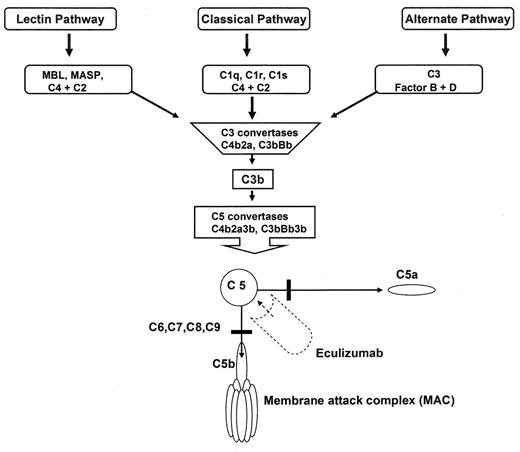

Eculizumab is a humanized monoclonal antibody against C5 that inhibits terminal complement activation (Figure 2 ). A 12-week open-label trial of eculizumab in 11 PNH patients demonstrated that the drug reduced intravascular hemolysis and transfusion requirements.40 A recent double-blind, randomized controlled trial known as TRIUMPH demonstrated that eculizumab was effective in stabilizing hemoglobin levels and reduced transfusion requirements in patients with classical PNH. Since terminal blockade of the complement cascade increases the risk for neisserial infections, all patients were vaccinated against Neisseria meningitides 2 weeks before receiving the study drug. The study randomized 87 PNH patients to receive either placebo (n = 44) or eculizumab (n = 43) administered intravenously at 600 mg weekly for 4 weeks, 900 mg the following week, and then 900 mg every 2 weeks for a total of 6 months. The primary endpoints were hemoglobin stabilization and reduction in units of transfused blood. Eligible PNH patients were required to be red cell transfusion dependent with a platelet count of ≥ 100,000 per mm3 and an LDH level ≥ 1.5 times the upper limit of normal. Hemoglobin stabilization was maintained by a median of 48.8% patients in the eculizumab-treated group and 0% in the placebo-treated group (P < 0.001). A median of 0 units of packed red cells were transfused in the eculizumab-treated group compared with a median of 10 units in the placebo-treated group (P, 0.001). The eculizumab-treated group also showed significant improvements in quality of life and a significant decrease in LDH levels. The most common adverse event reported for eculizumab-treated patients were headache, nasopharyngitis, back pain, and upper respiratory tract infections. Thus, in patients with classical PNH, eculizumab is highly effective in decreasing intravascular hemolysis; the drug greatly improves quality of life and reduces or eliminates the need for blood transfusions. Importantly, eculizumab also mitigates the smooth muscle dystonias that are often associated with PNH by reducing plasma free hemoglobin levels. Whether eculizumab will decrease the risk for thrombosis in PNH remains to be determined.

Overview of the complement cascade. Classic, alternative, and Lectin pathways converge at the point of C3 activation. The lytic pathway is initiated with the formation of C5 convertase and leads to the assembly of the C5, C6, C7, C8, (n) C9 membrane attack complex. Eculizumab is a monoclonal antibody that binds to C5, thereby preventing the formation of C5a and C5b. C5b is the initiating component of the MAC.

Overview of the complement cascade. Classic, alternative, and Lectin pathways converge at the point of C3 activation. The lytic pathway is initiated with the formation of C5 convertase and leads to the assembly of the C5, C6, C7, C8, (n) C9 membrane attack complex. Eculizumab is a monoclonal antibody that binds to C5, thereby preventing the formation of C5a and C5b. C5b is the initiating component of the MAC.

Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Division of Hematology, Baltimore, MD