Abstract

It is common knowledge that an allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) will have an enormous impact on the lives of transplant recipients and their families. Once an appropriate donor is identified, the curative potential of this treatment often drives the decision to proceed knowing that there will be intense physiologic toxicities and adverse effects on health-related quality of life (HRQL). Twenty-five years ago, HRQL was identified as an efficacy parameter in the evaluation of new anticancer drug therapy. Overall, the evidence suggests that an allogeneic HSCT has a significant impact on the overall HRQL of recipients, which is a result of decrements across all dimensions, including a significant symptom profile. The degree of impact on overall HRQL and the multiple dimensions varies across the transplant trajectory. Specific HRQL dimensions, such as physical function and symptoms, are easily incorporated into a clinician's assessment whereas other dimensions (eg, psychosocial) are less commonly integrated. The translation of HRQL results to improve clinical practice is not well established. Clinicians are often uncertain when to assess the scope of HRQL and how to interpret the information in a clinically meaningful way. The purpose of this review is to highlight the quality-of-life effects of allogeneic HSCT and discuss application into clinical practice.

It is common knowledge that an allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) will have an enormous impact on the lives of transplant recipients and their families. Once an appropriate donor is identified, the curative potential of this treatment often drives the decision to proceed despite the intense physiologic toxicities and the quality-of-life effects that seldom enter into a patient's decision about transplantation.1 The purpose of this paper is to define health-related quality of life (HRQL), highlight the major HRQL effects during allogeneic HSCT, and discuss the clinical application of the evidence to date and gaps that require further research. To address these objectives, the following case study will be referenced:

Mrs. Smith is a 28-year-old female with aggressive non-Hodgkin lymphoma refractory to six cycles of EPOCH-FR (a regimen consisting of etoposide, prednisone, vincristine, cyclophosphamide, and doxorubicin plus fludarabine and rituximab) who received a fully matched allogeneic HSCT from her brother. She has been married for 5 years and has a preschool-age daughter. Her husband serves as the primary caregiver, and the family relocated to a temporary house near the transplant center. The husband commutes to their primary residence (approximately 500 miles from the center) every week for 1 to 3 days in an attempt to maintain employment. In his absence, family or close friends provide support to assist with caregiving and child care. Mrs. Smith is day +30 postallogeneic HSCT. As an outpatient, her current transplant status is stable, with no acute transplant-related complications; ECOG = 1 (Eastern Cooperative Group Performance Status). Her major complaints include moderate pain (well controlled) from residual disease, low energy, and no appetite (weight stable).

What Is Quality of Life?

Quality of life is a broad term that refers to “an individual's perceptions of their position in life in the context of the culture and value systems in which they live and in relation to their goals, expectation, standards, and concerns.”2 HRQL captures the patient's perspective of the impact of illness or treatment on his/her life and consists of multiple dimensions.3 The multiple dimensions are critical to the concept of HRQL and are unique for the various health conditions. This complexity can create confusion for clinicians when determining what dimensions of HRQL to assess, and how to interpret the information in a clinically meaningful way.

Wilson and Cleary4 described HRQL in terms of biologic and physiologic variables, symptoms status, functional status, general health perceptions, and overall quality of life. This framework continues to be useful today with the broad categories (functional status) where more specific dimensions of HRQL—such as physical, social, role, and psychological function—are incorporated. No one dimension (eg, biologic/physiologic) can independently evaluate the impact of illness and treatment on an individual's life.

Why Is the Assessment of Quality of Life Important?

Twenty-five years ago, HRQL was identified as an important consideration in the evaluation of new anticancer drug therapy.5 The knowledge related to HRQL and its multiple dimensions has flourished since that time, with an emphasis on application in research, primarily in questionnaire validity and reliability, with little attention to application to clinical practice. Although clinicians often assess the impact of treatment with broad questions (eg, How are you doing?), a more formal approach to the inclusion of the patient's perspective has gained incredible momentum broadening to include all aspects of health. Patient-reported outcomes (PRO) are defined as any aspect of a patient's health status that is provided directly from the patient6 and are most commonly collected through the use of questionnaires.

A variety of benefits have been identified when adding PRO information into practice. Self-report questionnaires may prove an efficient way of gathering needed data about the patient's current health status, alert the clinician to problems that may require intervention, and ultimately improve patient outcomes.7 In addition to serving as a key element in treatment decision making, and in evaluating treatment efficacy, the collection of the patient's perspective has been shown to improve physician–patient communication.8 Improved communication and better shared decision-making reinforces ideas of patient autonomy and clinician beneficence, thereby assisting people to achieve their own personal notions of “a good life.”9

When a patient's perspective is not comprehensively incorporated into his/her assessment, the determination about health status may be inaccurate and, at times, incomplete. The conversation between clinician and patient may include discussion about HRQL, with a focus on symptom status and physical function.10 Despite this dialogue, transplant physicians often underestimate symptoms and overestimate function and overall HRQL.11 This discordance between the patient self-report and physician has been noted in the documentation of symptoms in the medical record.12 In addition, evidence suggests that patients report symptoms earlier and more frequently than clinicians.13

HRQL Effects Related to Allogeneic HSCT

The majority of the PRO information in allogeneic HSCT represents the recipients of a myeloablative conditioning regimen using related and unrelated donors. These findings are generally conditional on survival, which creates a bias on the outcomes that HSCT recipients can expect.14,15 Transplant recipients who are not represented in these studies are most likely too ill to complete questionnaires that would likely suggest significant impairments across all HRQL dimensions.

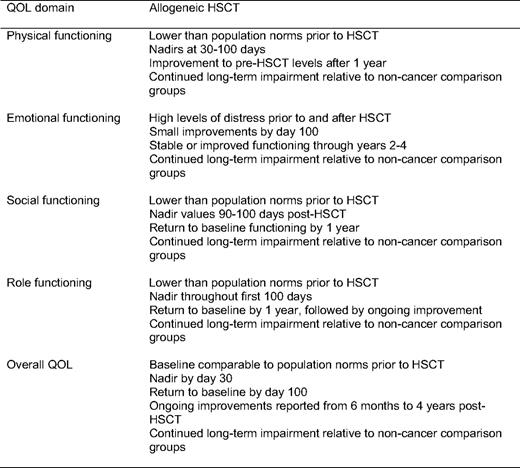

Recently Pidala and colleagues14 published a comprehensive review of HRQL in allogeneic HSCT. Findings from this review have been nicely summarized (Table 1) and reflect a fit with the predictable phases of allogeneic HSCT recovery. Specifically, the application of these findings can be considered in four phases: (1) pretransplant, (2) during transplant (through day 100), (3) immediate recovery (3 months-1 year), and (4) long-term recovery (beyond 1 year). This approach provides a framework that takes into consideration the primary objective of the recipient and his/her family (survival vs reintegration) and the primary team responsible for the recipient's care (transplant specialist or primary hematologist/oncologist).

Overall, the evidence suggests that an allogeneic HSCT has a significant impact on the overall HRQL of recipients that is a result of decrements across all individual dimensions, including a significant symptom profile.14,16 The degree of impact on overall HRQL and the multiple dimensions varies across the transplant trajectory (Figure 1). The impairments often begin prior to the HSCT, due to the disease itself or previous treatment. During the HSCT, physical effects (ie, physical function, symptoms) have the greatest impact. As the patient moves through the first year and beyond, the primary effects shift as the impact on social and role function become more evident. Psychological effects are present across all phases of HSCT. Psychological distress and negative mood states (ie, anxiety and depression) are most prevalent before and during the HSCT. During the later phases of transplant, patients report improvements in their level of distress along with interpersonal growth. Despite the overall improvements, worry is still commonly reported after allogeneic HSCT, possibly related to the continued uncertainty of relapse. Cognitive function has also been recognized as an area of concern, with recent evidence suggesting that cognitive function may not be a significant or long-lasting problem after allogeneic HSCT.17

The majority of recipients return to their baseline level of HRQL by 1 year postallogeneic HSCT.14 Although this often includes a return to work, there continues to be additional gains beyond the first year. Recipients experiencing chronic graft-versus-host disease (GVHD), however, are less likely than survivors without chronic GVHD to resume work activities.15 Overall, recipients unable to return to work report health-related issues as the cause. The major contributor to significant impairments beyond 1 year is chronic GVHD. Chronic GVHD generates significant impairments in physical function, with important mechanisms, including functional performance (eg, strength and endurance) and symptom bother.18 Despite continued impairment, survivors generally report a positive state that may be related to a response shift or change in the meaning of their HRQL, which might serve to balance negative cognitions about the transplant experience.19

Symptom status is one aspect of HRQL that is not captured well in the measures that assess overall HRQL. The evidence on the symptom experience for recipients of allogeneic HSCT is often extrapolated from the broader HRQL measures with a single symptom question (eg, Do you have pain?) or from clinician reports. Although symptoms are embedded in the common HRQL dimensions (eg, physical and emotional), a more comprehensive assessment is required before suggesting interventions.20 This seems obvious for the physical symptoms that are routinely assessed following allogeneic HSCT, wherein a provider would immediately expand assessment of pain if reported by a patient (eg, What makes it worse?). The expanded assessment is less predictable when the symptom is vague or has an emotional component (eg, fatigue or sadness). In the case study, it becomes clear that the symptom of fatigue (“low energy”) is multifaceted, with both a physical and emotional component that are likely to benefit from a more in-depth assessment.

When Mrs. Smith's symptom of “low energy” was explored, her hemoglobin was 9.0 g/dL, and she reported being “physically and mentally exhausted.” Although physically exhausted at night, she is unable to sleep well. When encouraged to discuss this symptom she reports that it is a struggle to participate in her daughter's care. She states that her husband has to do everything, and he is not able to be there for her emotionally. He will not touch her, much less be intimate. He is so busy balancing work, caregiving, and parenting for the family unit that she doesn't know how to talk about her emotional needs with him. She worries about him and what will happen to him and her daughter if the transplant doesn't work.

The symptoms reported by Mrs. Smith are among the most prevalent following allogeneic HSCT. Studies have found that the most prevalent symptoms reported by recipients include fatigue, psychological distress (eg, worry/anxiety), and gastrointestinal toxicities during the first 100 days,16,21 and fatigue, psychological distress, and sexual function during later phases of recovery.22,23 In the presence of chronic GVHD, the symptom profile is more extensive,24 suggesting that a comprehensive symptom assessment is critical and has been reported as very useful. Regardless of the presence of chronic GVHD, recipients with higher levels of symptom distress report inferior HRQL.16,23,25

Further research is also needed to guide our practice regarding the caregivers of patients receiving allogeneic HSCT. Family members frequently serve as the primary caregivers for the patient and may be a factor in receiving and surviving the allogeneic HSCT.26,27 Although our knowledge is still growing, caregivers consistently report impairments, including psychological distress and symptom concerns, such as impaired sleep and fatigue. Although caregiver distress has been shown to improve over time, studies suggest that caregivers have levels of psychological distress that are at least equal to and, in some cases, higher when compared with the patient and healthy groups.28 Despite the issues experienced, caregivers are less likely to seek services for themselves while serving as caregiver.28

Although we are moving forward in our understanding of the impact of allogeneic HSCT on the patient's HRQL, significantly less relative to the impact on family caregivers, clinicians should use caution in the application of this evidence in new populations with indications for allogeneic HSCT. Generally, little evidence exists to guide our understanding of the impact of allogeneic HSCT on the HRQL of recipients characterized by: (a) age ≥ 55, (b) multiple comorbidities, and (c) nonmalignant diseases. The impetus behind the expanded application for allogeneic HSCT lies in the evolution of reduced-intensity conditioning (RIC) regimens. The commonality across these subgroups is a characteristic that would otherwise put the patient at increased risk for morbidity and mortality, thus prohibiting an allogeneic HSCT as a treatment option. Specifically for individuals receiving RIC, the evidence to date suggests that overall HRQL recovers similarly to individuals receiving myeloablative conditioning with a more rapid return to baseline.21,29 Important to note in subgroups receiving RIC is that impairments in HRQL, specifically related to physical functioning, are evident prior to receiving RIC for allogeneic HSCT.21,29

How to Assess HRQL?

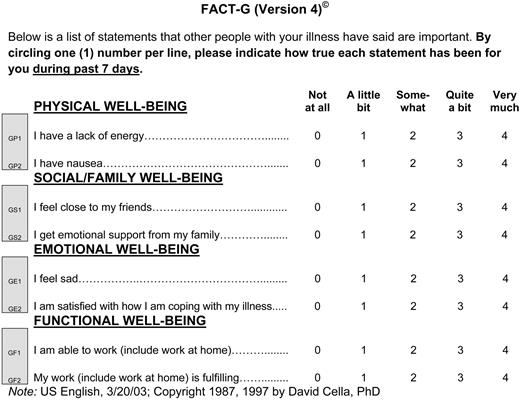

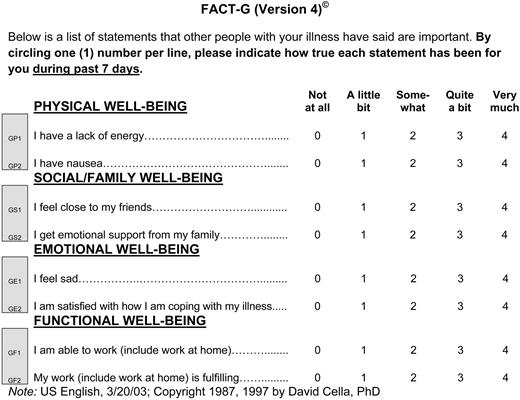

Clinicians often assess the overall impact of the procedure on a patient's life with simple questions such as, “How are you doing?” However, PRO questionnaires are a more systematic way to incorporate HRQL and its various dimensions into practice (Figure 2). This information represents the quantification of the patient's perspective of the impact of disease and treatment.3 Consistent with the definition of a scientific instrument, PRO questionnaires must provide precise, reliable, valid, and reproducible data, and quality criteria have been applied to common measures used in the oncology setting.30

The selection of a questionnaire to assess PROs, such as HRQL in a complex patient population, can seem daunting. The major characteristics of PRO instruments have been identified by the US Food and Drug Administration.6 As a clinician, a critical component in the assessment of HRQL is the context of the illness or treatment trajectory, with practical and relevant implications. Specifically, interpretation of the individual responses that involves (a) frequency of assessments, (b) immediate scoring and review of the questionnaire responses, (c) unaffected group comparisons (eg, what is normal), and (d) determination of clinically meaningful change (eg, how much change indicates that things are really different). Following an allogeneic HSCT, patients are seen often, and the screening and assessment of HRQL should be sensitive to the dimensions affected at that time without being perceived as a burden by the patient. Although comparison references to population norms may be available, the assessment of change over time for the individual patient is invaluable.31 This can be assessed by asking, “In comparison with last week, how is your fatigue?” or by using the standard for a clinically meaningful difference (eg, 2–3 point change) that may be available, depending on the questionnaires being provided to the patients. Scores, however, should always be interpreted in the context of the patient's complete clinical picture, recognizing that improvements may have more significance than declines to the individual patient.7,32

In determining which questionnaire might be best applied in a clinical setting for HRQL assessment, there are a variety of resources available for guidance. A review of generic, general cancer, and cancer site-specific measures of HRQL revealed that many were methodologically sound in the oncology population.33 The most common of these measures have been reviewed for their relevance in cancer34 and transplantation,14 providing insight on the components of HRQL that are assessed with each measure and should be considered when selecting measures in the context of transplant recovery. In addition, the PRO quality-of-life instrument database (QOLID) provides a web-based database that offers a relevant and updated overview of existing PRO instruments, and can facilitate choice and access to an appropriate measure.35

Application to Practice

The time has come to take PRO, and patient-centered care seriously.36 Overall, there seems to be a lapse in the assessment and application of current evidence in patients with hematologic diseases,37 unless they are receiving an allogeneic HSCT. This subgroup of individuals with hematologic diseases has been well studied. However, despite our knowledge with regard to the impact of allogeneic HSCT on HRQL, the systematic application of the evidence has yet to be achieved.

In this complex population, the scope of a patient visit can be overwhelming. Certain HRQL dimensions, such as physical function and symptoms, are easily incorporated into the clinician's assessment fitting well into the traditional biomedical evaluation of treatment toxicities. The psychological and social needs are less often addressed by providers,10 despite recent recognition by the Institute of Medicine38 asserting that quality cancer care is not possible without addressing the psychosocial needs of the patient.

The inclusion of PRO data into clinical practice should be considered another source of information that is assessed and incorporated into clinical care.39 In the context of allogeneic HSCT, three basic principles along the phases of recovery apply: (1) inform, (2) screen, and (3) intervene. To inform will occur primarily prior to the decision for transplant to ensure that a fully informed decision is made by the patient. This requires providers to understand the evidence that exists regarding the effects of allogeneic HSCT on the HRQL of recipients. Although patients may not consider the impact on their HRQL in the evaluation of alternative therapies when allogeneic HSCT is an available option, the majority of physicians are incorporating HRQL content into patient discussions. The scope of the discussion is less clear, with some evidence that the less overt effects related to the toxicities of treatment are less commonly discussed, such as sleep disturbance and psychosocial effects. Awareness of the patient's psychosocial profile prior to HSCT can also inform providers and influence their determination that an individual may or may not be a good candidate for allogeneic HSCT. If specific behaviors or issues of concern are identified, the provider can proactively suggest additional support during treatment.40

Documenting a clearly positive impact on practice by adding PRO measures in clinical oncology has not been convincing.41 The discussion to inform a potential transplant subject could be enhanced by baseline screening of HRQL status to individualize current and future assessments. This early expanded assessment would provide a guide for focused referrals prior to or during the process of transplantation to diminish common effects and encourage active and collaborative coping by the patient and caregiver serving to reduce overall distress.42

As a procedure that involves multiple toxicities, hospital readmissions, and significant uncertainty, an expanded assessment and screening for early detection of problems is essential. Screening for problems related to HRQL, specifically psychosocial effects, is feasible and informative in HSCT recipients.43 The completion of an HRQL questionnaire prior to a clinic visit can allow for appropriate referrals to be made prior to the patient's arrival, including health professionals that support psychological distress or specific symptom management, such as pain.44

To determine when to intervene on a specific problem requires a provider to understand the problem or a degree of change that is clinically meaningful. Many times, the easiest and most effective intervention is to stimulate a more in-depth assessment of a recognizable problem. For example, if a patient reports a level of psychological function that is perceived as “worse” by the patient since the last visit or exceeds the normative values for the scale, a referral to a clinician in the institution that could complete a thorough assessment for anxiety and depression may be warranted. This interprofessional collaboration can improve the quality of health care provided to patients.45

The anxiety and sadness evident in Mrs. Smith's report would likely benefit from a focused referral to a social worker or mental health specialist. Her poor sleep and physical and mental exhaustion are likely to make her transplant recovery more challenging. In addition, her husband may need emotional and practical support, which could be offered in the context of his caregiving role. Improvements in the emotional and behavioral aspects of the transplant experience may allow for additional interventions, such as structured exercise to improve her endurance.

Intervention studies to improve the HRQL outcomes in allogeneic HSCT recipients are limited. Recent studies with cancer patients and their family support the beneficial effect of interventions based on cognitive-behavioral therapy46–48 to manage psychological distress, treatment, and disease-related symptoms. In addition, sufficient evidence exists to support exercise as an intervention to enhance a cancer patient's physical functioning and psychological well-being.49 Studies testing the benefit of exercise programs with allogeneic HSCT recipients suggest that the evidence is insufficient to make recommendations for specific interventions to improve HRQL.14,50,51 Although favorable outcomes specifically related to physical function have been reported with no untoward effects, across all studies strict guidelines for participation were applied, suggesting caution before applying these findings into practice.

Finally, the practical resource issues specific to the collection of PRO data need to be considered. A major obstacle to incorporating PRO data into a clinician setting is the challenge of real-time questionnaire completion, scoring, and interpretation. However, as computerized systems are more widely applied, the feasibility of computerized screening programs is being reported.52 Specifically, in allogeneic HSCT patients, a web-based program for routine collection of quality-of-life outcomes was promising.53 For broader application, Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) has been developed, providing a computerized adaptive testing system that allows for the efficient, psychometrically robust assessment of patient-reported outcomes for a wide range of chronic disease outcomes.54

Conclusions

Formal guidelines have not been developed to guide the major assessment time points for allogeneic HSCT recipients. There is sufficient evidence to date to document the importance of adding PROs to routine clinical practice with reliable, valid measures to be considered. Providers do not need to spend time contemplating what HRQL is or how it can be measured. The focus needs to be on the when and where to include this evidence in clinical care so that this complex population receives the highest level of care across all dimensions of their life during recovery following allogeneic HSCT.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks the following individuals for their thoughtful review of this paper: Cynthia Dunbar, Gwenyth Wallen, and Leslie Wehrlen.

Disclosures

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The author declares no competing financial interests.

Off-label drug use: None disclosed.

Correspondence

Margaret Bevans, RN, PhD, AOCN, 10 Center Dr., MSC 1551, Room 2b13, Bethesda, MD 20892; Phone: (301) 402-9383; Fax: (301) 480-9675; Email: mbevans@cc.nih.gov

Off-label drug use: None disclosed.