Abstract

Transfusion of blood and blood components has been a routine practice for more than half a century. The rationale supporting this practice is that replacement of blood loss should be beneficial for the patient. This assumption has constituted the underpinning of transfusion medicine for many decades. Only over the past 20 years, we have seen a more concerted effort to answer very basic questions regarding the value of transfusion therapy. An assessment of the value of transfusion based on well-designed and appropriately powered randomized, controlled trials is the first step in optimizing transfusion practices. Systematic reviews provide the second step by building the knowledge base necessary to assess the impact of transfusion practice on patient outcomes. The third step is the development of clinical practice guidelines, and this occurs when systematic reviews are interpreted by individuals with expertise in transfusion medicine. Such guidelines are typically supported by professional organizations and/or health authorities. Implementation of clinical practice guidelines can be challenging, especially in an area as heterogeneous as transfusion medicine. However, clinical practice guidelines are necessary for the practice of evidence-based medicine, which optimizes patient care and improves patient outcomes. This review focuses on clinical practice guidelines for transfusion of three blood components: RBCs, platelets and plasma. In addition, we provide the approach used to implement clinical practice guidelines at our own institution.

Introduction

Transfusion of blood and blood components (ie, RBCs, platelets, plasma, and cryoprecipitate) is one of the most common medical procedures performed in the developed world. However, the decision to transfuse or not to transfuse is one of the more complex decisions made by medical practitioners. Clearly no medical intervention is without risks, but in principle, these risks should be offset or justified by immediate or long-term benefits.

A better understanding of the risks of transfusion has transformed transfusion medicine through the accelerated development of more sophisticated donor testing (eg, ever-improving infectious disease tests), pretranfusion testing, recipient identification, and multiple improvements in blood component characteristics and quality (eg, leukoreduction, irradiation, pathogen inactivation). These developments have resulted in improved safety profiles for transfused components and a perception of minimal risk. At the same time, the introduction of patient blood management (PBM), defined as an evidence-based approach to optimizing the care of patients who might need transfusion, shows that the need for transfusion can be minimized in many patients by implementation of thoughtful processes often beginning days or even weeks before the actual decision to transfuse or not is being made.

In this context, the focus has now shifted to the benefit side of the equation. Are the assumed benefits of transfusion universal or are they limited to only a well-defined population of patients? What triggers should be used to administer blood components and when should transfusions occur? What component dose is sufficient and/or necessary to confer clinical benefit? The answers to these questions have been sought in multiple randomized clinical trials. The next step of this process is to translate this information into widely adopted and consistent practice through the development of clinical practice guidelines that can become a part of comprehensive PBM.

Clinical practice guidelines are defined as systematically developed statements to assist with practitioner and patient decisions about appropriate health care for specific clinical circumstances.1-3 There is a growing body of literature on the best approaches to develop clinical practice guidelines. One system that is used more frequently than others is the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) system.4 This process-oriented approach provides for significant uniformity in arriving at recommendations and making them clinically relevant. After clinical practice guidelines are developed, their adoption by individual physicians, clinical practices, and healthcare systems is accomplished in different ways. Initial broad-based education efforts are strengthened by the development of critical pathways, hospital policies, and systems to support adherence.

Although the development of clinical practice guidelines is time consuming and expensive, several professional societies and health authorities have participated in the development of transfusion-specific clinical practice guidelines to support evidence-based transfusion practice. These clinical practice guidelines support optimization of patient outcomes and appropriate utilization of limited and costly resources and allow for transfusion medicine physicians to become an integral part of the treatment team.5 Successful implementation of clinical practice guidelines in transfusion medicine can often be supported by computerized physician order entry systems and order auditing.

In this short review, we highlight current clinical practice guidelines regarding transfusion of RBCs, platelets, and plasma and illustrate how these guidelines are integrated into clinical practice at our own institution with support from our electronic medical record system. This can be also considered as the first step to implementation of comprehensive PBM.

Guidelines for RBC transfusion

The development of clinical practice guidelines for RBC transfusion has been challenged by a limited availability of high-quality evidence to support practice recommendations. There is general agreement that RBC transfusion is typically not indicated for hemoglobin (Hb) levels of > 10 g/dL and that transfusion of RBCs should be considered when Hb is < 7 to 8 g/dL depending on patient characteristics.6,7 The decision to transfuse RBCs should be based on a clinical assessment of the patient that weighs the risks associated with transfusion against the anticipated benefit. As more studies addressing RBC transfusion become available, it becomes increasingly clear that liberal transfusion strategies are not necessarily associated with superior outcomes and may expose patients to unnecessary risks.

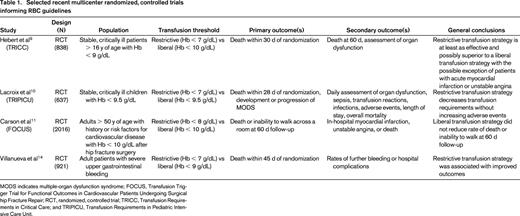

The most recently published guidelines from the AABB (formerly the American Association of Blood Banks) are based on a systematic review of randomized, controlled trials evaluating transfusion thresholds.8 (selected trials are presented in Table 1) These guidelines recommend adhering to a restrictive transfusion strategy and consider transfusion when Hb is 7 to 8 g/dL in hospitalized, stable patients. This strong recommendation is based on high-quality evidence from clinical trials comparing outcomes in liberal versus restrictive transfusion strategies in this patient population.9-11 A restrictive transfusion strategy is also recommended for patients with preexisting cardiovascular disease. In this population, transfusion should be considered when Hb levels are < 8 g/dL or for symptoms such as chest pain, orthostatic hypotension, tachycardia unresponsive to fluid resuscitation, or congestive heart failure.8 This weak recommendation is based on moderate-quality evidence due to limited clinical trial data directly addressing this population of patients. Additional clinical practice guidelines exist that specify Hb targets for critical care patients with conditions including sepsis, ischemic stroke, and acute coronary syndrome.12,13

RBC transfusion is indicated in patients who are actively bleeding and should be based on clinical assessment of the patient in addition to laboratory testing. Much remains to be learned about the optimal resuscitation of the bleeding patient, and this topic is outside of the scope of this review. However, a recent study examining transfusion in patients with active upper gastrointestinal bleeding showed superior outcomes in patients treated with a restrictive transfusion strategy (< 7 g/dL).14

At our institution, patients with active and clinically significant bleeding are transfused with RBCs as needed to meet the clinical needs of the patient and to optimize laboratory values. Laboratory monitoring of the Hb level is performed to assess the response to transfusion and the need for ongoing blood component support. Transfusion Medicine Service (TMS) physicians are available on call at all times to assist with the appropriate transfusion support of patients requiring massive transfusion.

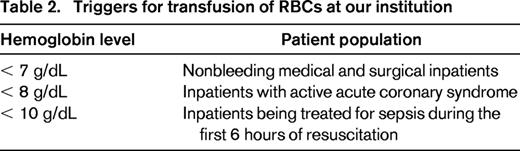

Our guidelines for RBC transfusion in stable nonbleeding patients were developed by the transfusion committee in collaboration with medical and surgical providers based on a synthesis of existing clinical evidence, practice guidelines, and institutional preferences (Table 2). Stable, nonbleeding medical and surgical inpatients patients are considered candidates for RBC transfusion when the Hb level is ≤ 7 g/dL.9 Transfusion should be considered for inpatients with active acute coronary syndromes with an Hb level ≤ 8 g/dL.13 Adult critical care medical and surgical inpatients being treated for sepsis during the first 6 hours of resuscitation may be transfused with an Hb level ≤ 10 g/dL.15 All RBC transfusions in nonbleeding inpatients should be ordered as single units. If transfusion is indicated based on Hb level, posttransfusion Hb must be obtained before ordering additional units.

Our computerized physician order entry system is configured to automatically query the most recent Hb value when an order for inpatient RBC transfusion is placed. If the most recent Hb is > 7 g/dL or has not been measured in the past 24 hours, the physician receives a best practice alert prompting them to select from a limited menu of appropriate indications or cancel the transfusion order. In addition, all orders are retrospectively audited to ensure compliance and to provide education to providers practicing outside of these guidelines.

Guidelines for platelet transfusions

It has been shown that patients with severe thrombocytopenia are at increased risk of bleeding. Platelet transfusions can be administered either as a prophylactic to minimize the risk of bleeding or as a therapeutic to control bleeding. It has been assumed for many years that transfusion of platelets should decrease the bleeding risk in the patients with hypoproliferative thrombocytopenia (eg, post myelosuppressive chemotherapy). Early guidelines for platelet transfusion developed in 1980s and 1990s relied primarily on systematic reviews of the literature available at the time, which primarily consisted of small trials.16 The initial guidelines recommended transfusion of nonbleeding patients at the level of 20 000/μL. This value was extrapolated from the observation that there is significantly increased risk of bleeding when the platelet count is < 5000/μL and the risk of bleeding does not seem to change between 10 000/μL and 100 000/μL.16 Several studies in different patient populations has shown that there is no difference in bleeding risk between a platelet count of 10 000/μL and a count of 20 000/μL.17,18 It has been also observed that ∼ 7100/μL/d is necessary for interaction with the endothelium.16,19

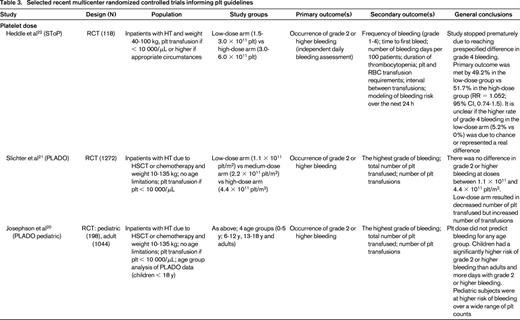

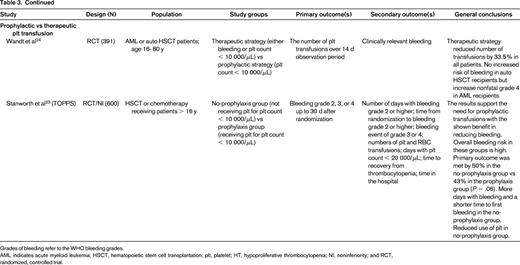

Recently, several important randomized trials and systematic reviews were completed that have further clarified platelet transfusion triggers17 ; these include: platelet dosing (Prophylactic Platelet Dose Trial [PLADO] and subsequent analysis;20,21 Strategies for Transfusion of Platelets [SToP]22 ); type of platelet component (eg, apheresis vs whole blood–derived platelets; leukoreduction; HLA matching; pathogen inactivation); and therapeutic versus prophylactic platelet transfusion (Trial of Prophylactic Platelets [TOPPS]23 ; Study Alliance Leukemia24 ; Cochrane review25 ). A summary of the randomized, controlled trials is presented in Table 3. These studies have also shown that bleeding in hypoproliferative thrombocytopenia is common and decreases with age (starting at 86% in the 0 to 5 years of age group and decreases to 50% in adults).20,21,23 Interestingly, bleeding occurs at any platelet range and prophylactic transfusions have only limited impact on bleeding frequency. However, patients receiving prophylactic transfusions do have a delayed onset of bleeding.23,25 It has also been established that a lower dose of platelets is noninferior to a larger dose when measured by incidence of World Health Organization (WHO) Grade 2 or above bleeding.21,22 It has also become apparent, however, that there remain challenges in how the bleeding is measured and reported. The Biomedical Excellence for Safer Transfusion (BEST) Collaborative (www.bestcollaborative.org) analyzed the heterogeneity in reporting of the amount and type of documented bleeding in 13 clinical trials of platelet transfusions.26 They concluded that consensus bleeding definitions, a standardized approach to record and grade bleeding, and guidance notes to educate and train bleeding assessors are necessary to be able to attribute observed bleeding differences to studied interventions.

The most recent clinical practice guidelines on platelet transfusions were developed by the American Society of Clinical Oncology for cancer patients in 2001 and by the British Committee for Standards in Haematology in 2003.27,28 We are aware of ongoing preparation of 2 new clinical practice guidelines for platelet transfusion. The first is being prepared by the International Collaboration for Guideline Development, Implementation, and Evaluation for Transfusion Therapies (ICTMG) and should be finalized and available this year. The second is being prepared by the AABB and is likely to be available in 2014. Because the methodologies for the development of these guidelines are not identical, there is a possibility that they may differ in their final recommendations.

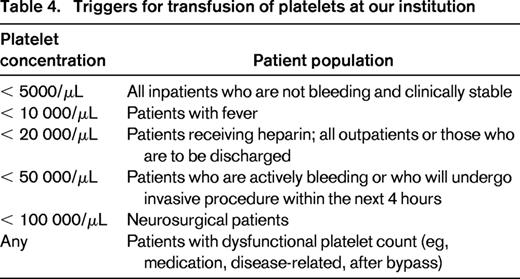

At our institution (Table 4), inpatients not actively bleeding are only transfused when the platelet count is < 5000/μL. This threshold was introduced in our institution and approved by the providers 18 years ago based on the publication by Gmür et al.29 Patients with a temperature ≥ 38°C or with recent hemorrhage can receive platelets with platelet count < 10 000/μL. If the patient is on heparin, has coagulopathy, or has an anatomic lesion that is likely to bleed or is an outpatient, the trigger is placed at 20 000/μL. Patients who are bleeding or have scheduled an invasive procedure within the next 4 hours can be transfused for platelet count < 50 000/μL. Finally, the trigger for the patients with CNS bleeding is 100 000/μL. The last 2 thresholds have no data to support or refute their benefit. There is no trigger for patients with dysfunctional platelets due to underlying platelet function disease or medication affecting platelet function. However, in both situations, the TMS physician is involved in helping to establish the dose and frequency of transfusion if multiple transfusions are required. For the common bedside procedures such as central line placement, lumbar puncture, and BM biopsy, the threshold is provider and service dependent and falls between 20 000 and 50 000/μL. This is an area where we see an opportunity to further standardize our institutional approach.

The criteria for administration of platelets at our institution have not changed since 1995. Platelet concentrates (exclusively apheresis platelets) are ordered using an electronic order entry system in which the ordering physician is prompted to select the appropriate indication from a limited menu of options. If the patient does not meet the established criteria (Table 4) or the most recent platelet value is inconsistent with the selected indication, the request is referred to a TMS physician (ie, resident, fellow, or attending) for further investigation.5 This conversation between the ordering physician and TMS physician may lead to the release of platelets or denial based on the clinical circumstances. This system, which has been in place for almost 20 years and is supported by real-time education provided by the TMS physicians to ordering providers, has led to significantly improved compliance with our platelet transfusion guidelines.

Guidelines for plasma transfusions

Plasma for transfusion is produced from volunteer donation of either whole blood or apheresis plasma and is labeled as fresh frozen plasma when frozen within 8 hours of collection or plasma frozen within 24 hours (FP24). Both products are considered clinically equivalent and are typically transfused using a weight-based dosing of 10 to 20 mL/kg of recipient weight. Once thawed, either product must be transfused within 24 hours or be relabeled as “thawed plasma” to allow for refrigerated storage for up to 5 days.30 Although degradation of the labile clotting factors V and VIII is observed during refrigerated storage, there is an overall maintenance of coagulation factors at sufficient levels for therapeutic use.30 Risks associated with plasma transfusion include allergic reactions, transfusion-related circulatory overload, transfusion-related acute lung injury, and transfusion-transmitted infections.31 Several pathogen-reduced plasma products are currently available for use outside of the United States and one has been recently approved for use in the United States.30

Currently, randomized, controlled clinical trial evidence to guide plasma transfusion practice is lacking. Published guidelines based on “expert opinion” support the transfusion of plasma for the following clinical indications: active bleeding in the setting of multiple coagulation factor deficiencies (massive transfusion, disseminated intravascular coagulation); emergency reversal of warfarin in a patient with active bleeding in settings where prothrombin complex concentrate with adequate levels of factor VII is not available; and for use as replacement fluid when performing plasma exchange, particularly in the treatment of thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura.32-36

However, in addition to these accepted indications, a significant amount of plasma is currently used in settings where there is a lack of evidence demonstrating clinical benefit.37 One common reason that plasma is requested is to normalize an elevated international normalized ratio (INR) before a planned surgery or invasive procedure.38 The faulty assumptions in this situation are that the elevated INR correlates with a risk for bleeding and that plasma transfusion will normalize the INR and reduce this risk.39

However, an analysis of available studies demonstrated that a mildly elevated INR is not predictive of an elevated risk for bleeding.40 Further, for mild prolongation of the INR (1.1-1.85), transfusion of plasma has not been shown to significantly improve the INR value.41 The INR calculation was developed to standardize variations in clotting times between institutions using different testing reagents for the sole purpose of monitoring patients on warfarin. Use of the INR has never been validated in other patient populations. In patients with liver disease, analysis of factor levels over an INR range of 1.3 to 1.9 demonstrated mean factor levels that were adequate to support hemostasis (> 30%).42

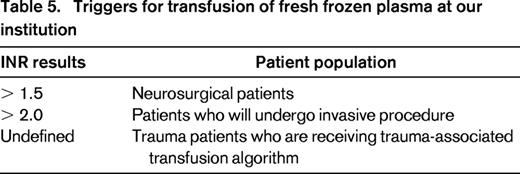

At our institution (Table 5), patients with evidence of hemorrhagic shock or active bleeding leading to hemodynamic instability are transfused with plasma as needed to optimize laboratory values. Laboratory testing must be performed to assess the response to transfusion and the need for ongoing blood component support. If plasma transfusion is indicated to correct an elevated INR, a posttransfusion INR must be obtained before ordering additional plasma. Patients with an INR ≥ 2.0 (≥ 1.5 for neurosurgical patients) are considered appropriate candidates for plasma transfusion. Plasma is ordered using patient-weight-based dosing and all orders that are not consistent with weight-based dosing are investigated before plasma is dispensed.

As described above for platelets, all orders for plasma at our institution are prospectively reviewed to ensure both appropriate indications and dosing. Potentially inappropriate orders are referred to a TMS physician (ie, resident, fellow, or attending) for further investigation.

Conclusions

There are an increasing number of high-quality clinical practice guidelines addressing transfusion of blood components. These guidelines are based on increasing numbers of high-quality randomized clinical trials that have been completed over the past 15 years. The implementation of clinical practice guidelines into the routine practice of medicine can be supported through the use of electronic health records and physician order auditing.

Disclosures

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: Z.M.S. is on the board of directors or an advisory committee for AABB, National Marrow Donor Program, Fenwal/Fresenius Kabi and Grifols Inc and is employed by Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center. N.M.D. declares no competing financial interests. Off-label drug use: None disclosed.

Correspondence

Zbigniew M. Szczepiorkowski, Department of Pathology, Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center, One Medical Center Drive, Lebanon, NH 03756; Phone: 603-653-9907; Fax: 603-650-4845; e-mail: ziggy@dartmouth.edu.