Learning Objective

To compare the efficacy and adverse effects of prothrombin complex concentrate and plasma for rapid correction of vitamin K antagonist-associated hemorrhagic emergency

Clinical vignette

A 78-year-old female presents to the emergency department with brisk hematochezia, fatigue, and tachycardia. She is receiving chronic oral anticoagulant therapy with warfarin as thromboprophylaxis for a mechanical mitral valve. International normalized ratio (INR) is 4.2. Red blood cell transfusion is ordered, and 10 mg of intravenous vitamin K is given. You are asked whether plasma or prothrombin complex concentrate is more effective for emergent reversal of her warfarin-associated coagulopathy.

Warfarin is a vitamin K antagonist (VKA) that has been the mainstay of oral anticoagulant therapy for the prevention and treatment of thromboembolism. Bleeding is the major complication of anticoagulant therapy with rates of major warfarin-related bleeding up to 7% reported depending on the indication for anticoagulation and study design.1-5 Warfarin use increases the risk of major bleeding by 0.3%-0.5%/year and intracranial hemorrhage (ICH) by 0.2%/year compared to controls in clinical trials.1 Despite the availability of warfarin-reversal agents, warfarin-associated bleeding leads to significant morbidity and mortality, with case fatality rates of 8%-13%.5-8 Death in hospital or within 7 days of discharge has been reported in 18% of warfarin-treated atrial fibrillation patients presenting with major bleeding.9 In patients presenting with warfarin-associated ICH, high mortality rates of 54% and 64% have been reported at 30 days and 6 months, respectively.10

Although direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) are now approved for several indications, warfarin use is expected to continue for patients who are stably managed on long-term warfarin therapy, conditions in which DOACs are not proven (eg, antiphospholipid antibody syndrome, mechanical heart valves), patients with severe renal failure (creatinine clearance <30 mL/min), and patients for whom DOACs are cost prohibitive.

Warfarin-associated major bleeding complications require urgent reversal of coagulopathy. When given intravenously, the effect of vitamin K on warfarin coagulopathy is evident within 6 hours. Plasma contains all coagulation factors and will correct coagulation factor deficiency attributable to inadequate synthesis. Time to thaw frozen plasma (FP) may in some circumstances be a limitation, but large blood banks typically have a continuous stock of thawed plasma. The infusion time depends on vascular access and volume status of the patient. Fluid overload and mild allergic reactions are the most common adverse reactions to plasma (∼1 in 100 transfusions). Serious allergic and transfusion-related acute lung injury reactions are rare (∼1 in 10 000 transfusions).11-16

Prothrombin complex concentrates (PCCs) are plasma-derived products containing vitamin K-dependent factors II, VII, IX, and X (4-factor PCC) or II, IX, and X (3-factor PCC), with some formulations also containing proteins C and S and heparin. PCC is stored as a lyophilized powder at room temperature, does not require blood group determination, can be administered by rapid infusion, and undergoes viral inactivation.17 PCC has a higher product cost and has been associated with thromboembolic complications when used to reverse VKA coagulopathy.18

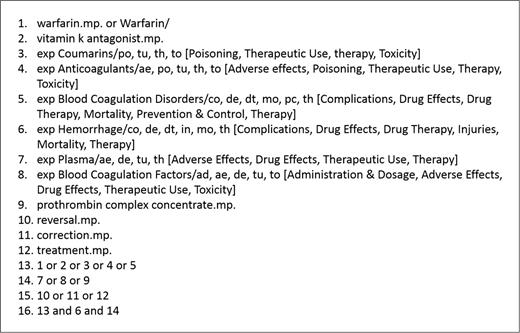

We conducted a systematic review to evaluate the current best evidence regarding the comparative efficacy and safety of PCC or plasma for warfarin reversal in the setting of major bleeding. Using standard systematic review methodology, we conducted a search of OVID Medline from inception to June 18, 2015. Studies were eligible for inclusion if they were randomized controlled trials (RCTs) or observational studies comparing treatment with PCC or plasma for warfarin-associated bleeding in adult patients (aged ≥18 years) and written in English. Pediatric studies, animal studies, abstracts, articles lacking original data, non-English studies, noncomparative studies, and studies using plasma/PCC for indications other than major bleeding were excluded. The search strategy used Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) and keyword searches as shown in Figure 1.

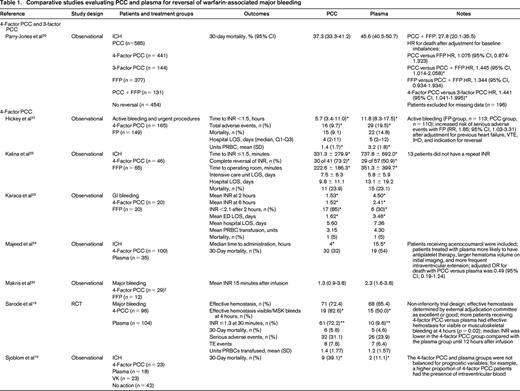

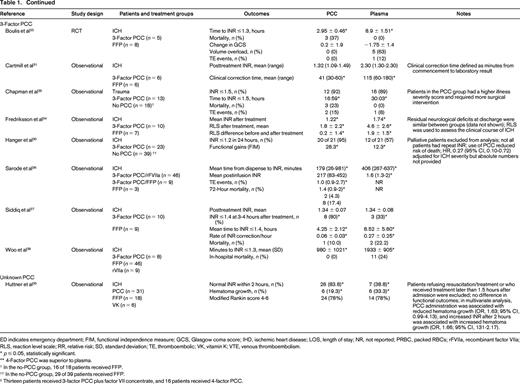

The literature search yielded 1504 potentially eligible studies. An additional 6 studies were identified from a manual review of reference lists. One study was included after the initial search strategy was conducted. Therefore, 17 studies were included in the final review (Table 1). Only 2 studies were RCTs, with the remainder being observational studies. In general, the studies had small sample sizes (range of 12-1547 patients). Eleven studies (65%) included <100 total patients. Patient populations were heterogeneous; the majority of studies included patients with warfarin-associated ICH (n = 12, 71%), followed by major bleeding (n = 3, 18%), gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding (n = 1, 6%), and trauma (n = 1, 6%). Individual studies also varied with respect to treatment protocols, PCC dosing, and additional interventions, such as vitamin K. Except for the RCT by Sarode et al,19 the studies were of low methodologic quality and subject to bias.

Hemostatic efficacy was evaluated in one non-inferiority RCT by a blinded external adjudication committee using a hemostatic efficacy scale.19 The proportion of patients experiencing effective hemostasis defined as “excellent or good” over 24 hours was similar between the PCC and plasma groups [72.4%; 95% confidence interval (CI), 63.6%-81.3%; and 65.4%, 95% CI, 56.2%-74.5%; p = 0.0045 for non-inferiority].

Of 11 studies reporting mortality, 2 observational studies showed differences between treatment groups. After adjusting for differences in baseline patient characteristics, Parry-Jones et al showed a similar risk of death with PCC and plasma [hazard ratio (HR), 1.075; 95% CI, 0.874-1.323; p = 0.492].20 There were statistically significant increased risks of death with no reversal (HR, 2.540; 95% CI, 1.784-3.616; p < 0.001) and use of PCC alone (HR, 1.445; 95% CI, 1.014-2.058) compared with reversal with both plasma and PCC. Patients receiving 4-factor PCC had a higher risk of death than those receiving 3-factor PCC (HR, 1.441; 95% CI, 1.041-1.995; p = 0.027). The study by Sjoblom et al21 did not adjust for baseline imbalance in prognostic features (higher proportion of PCC patients had intraventricular blood present on imaging) and showed a statistically significant difference in mortality in favor of the plasma group (11.5% versus 39.1%; p < 0.05). In the Sarode et al19 non-inferiority RCT, the adjusted odds ratio (OR) for death with PCC versus plasma was 0.49 (95% CI, 0.19-1.24). The remainder of studies showed no difference in mortality, although they were likely underpowered to detect differences.19,22-28

There were no differences in the duration of hospital admission in 3 studies reporting this outcome.22,23,29 One study showed an improvement in functional gains in patients receiving PCC versus plasma after warfarin-associated ICH as measured by the functional independence measure.30 Of 3 studies evaluating red blood cell (RBC) transfusion, only the study by Hickey et al showed a reduction in the mean units of RBCs transfused.19,22,29 Adverse events were included infrequently as study outcomes (n = 4 studies), but there were fewer total events with PCC and no difference in thrombotic rates in 3 studies.19,22,25,26

For the remainder of the studies, efficacy was evaluated predominantly using surrogate outcomes, such as INR correction, which is a known poor predictor of clinical hemostasis. In 7 studies, administration of PCC was associated with reduced time to INR correction (as defined in individual studies) compared with plasma.22-28 Two studies showed reduced time from product administration to laboratory testing with PCC compared with plasma.31,32 In 3 of 6 studies, the mean posttreatment INR was reduced significantly in patients receiving PCC compared with plasma.27,29,31-34 The proportion of patients achieving INR correction (as defined in individual studies) was significantly greater in patients receiving PCC compared with plasma in all 5 studies reporting this outcome.26,27,29,30,35

Reversal of warfarin anticoagulation for major bleeding requires administration of vitamin K to reestablish the activity of vitamin K-dependent coagulation factors, an effect seen at least 6 hours after intravenous administration. Adjunctive replacement of coagulation factors with PCC or plasma contribute to the rapid normalization of hemostasis desired in the setting of major bleeding. Together, the results of this review suggest that, when compared with plasma, PCCs result in faster INR correction; however, the effect on clinical outcomes, such as mortality and thromboembolic events, is unclear because of the low methodologic quality of available studies. There was only one high-quality RCT that found PCC to be non-inferior with respect to hemostatic efficacy, mortality, and adverse events.19 Given the morbidity and mortality associated with warfarin-related bleeding complications, especially ICH, high-quality studies evaluating patient-important clinical outcomes are needed.

Conclusion

There is grade 2B evidence that supports using PCCs or fresh frozen plasma (FFP) as a supplement to vitamin K for urgent reversal of VKA-associated hemorrhage (weak recommendation, moderate-quality evidence). The patient in the clinical scenario received intravenous vitamin K and 35 IU (factor IX)/kg 4-factor PCC in addition to the vitamin K. INR was 1.9 at the first measurement 1 hour after infusion. Hematochezia stopped within 24 hours, and the patient proceeded to endoscopy to guide additional management. Despite the rapid INR reversal, current evidence does not clearly inform whether the outcome at 24 hours would have been meaningfully different after vitamin K and FFP infusion or after intravenous vitamin K alone.

Correspondence

Dr Deborah M. Siegal, Division of Hematology and Thromboembolism, McMaster University, 50 Charlton Avenue East, L-208, Hamilton, ON L8N 4A6, Canada; Phone: 905-521-6024; Fax: 905-540-6568; e-mail: deborah.siegal@medportal.ca.

References

Competing Interests

Conflict-of-interest disclosures: D.M.S. has participated in advisory boards for Boerhinger Ingelheim, Portola Pharmaceuticals, and Daiichi Sankyo and has developed educational material for Interactive Forums. W.J.S. has received research funding from Fresenius-Kabi and has consulted for Momenta Pharmaceuticals.

Author notes

Off-label drug use: None disclosed.