Abstract

Stem cell transplantation (SCT) and palliative care (PC) may initially appear to be distant extremes in the continuum of care of patients with hematologic malignancies, opposed by multiple obstacles preventing their integration. Rather, we will posit that both fields share many similarities and have much to learn from one another. PC has increasing relevance in cancer care given recent studies that link PC to improved quality-of-life, survival, and decreased cost of care. Understanding modern conceptualizations of PC and its role within SCT is key. Through the report of a single academic medical center experience with an integrated SCT and PC model over the last decade, we will discuss future opportunities for strengthening collaboration between SCT and PC. PC in SCT should be considered from the day of diagnosis and tied to need, not to prognosis.

Learning Objectives

Describe the similarities between stem cell transplantation (SCT) and palliative care (PC) practice and highlight areas for cooperation

Define what PC is and is not, and describe the unique role of PC in the SCT setting

List future opportunities for PC and SCT collaboration and growth

Measuring the distance

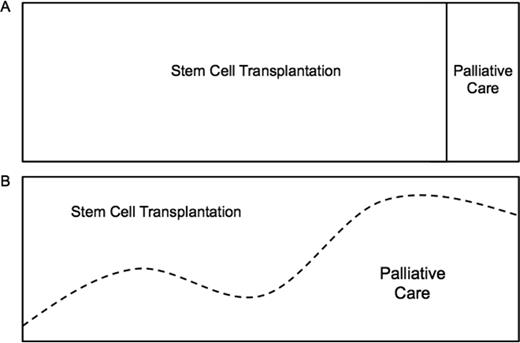

Stem cell transplantation (SCT) and palliative care (PC) appear to be distant extremes in the continuum of care of patients with hematologic malignancies. At one end is SCT, a cutting edge, aggressive clinical approach with an intense focus on treating disease with potentially life-sustaining treatments that carry significant risks. On the other end is PC, with a broad focus on the patient experience and an emphasis on maximizing or maintaining quality of life. Most clinicians believe these are conflicting approaches to care, with aggressive treatment at one end and “giving up” at the other (Figure 1A). As such, patients with hematologic malignancies are the least likely to be referred to PC. Instead, they are more likely to receive aggressive therapy at the end of life, die in an intensive care unit, and, when available, receive late PC referrals. That is, if a referral is placed at all.1,2 Obstacles to the integration of SCT and PC include misperceptions, limited resources and PC expertise, as well as disease-specific variables.3 These obstacles have created an “all-or-none” care delivery model that is antiquated and does not meet the needs of patients, caregivers, or clinicians (Figure 1A). In this article, we challenge this dichotomous model by first discussing potential areas of overlapping interests in our fields, describing barriers to integration, and then present our own experience with an integrated PC and SCT unit.

The continuum of care in stem cell transplantation. (A) “All or none” approach. (B) Early, simultaneous PC integration into SCT standard of care.

The continuum of care in stem cell transplantation. (A) “All or none” approach. (B) Early, simultaneous PC integration into SCT standard of care.

Building bridges, not walls

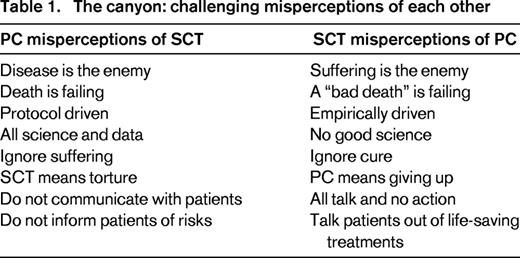

Bridges are structures built to provide passage over obstacles. The first step in building a bridge between SCT and PC is recognizing our similarities and challenging misconceptions of one another (Table 1). We have more in common than most might think. Both SCT and PC are intensely focused on exceptional care of patients with advanced illness. Most medical clinicians that gravitate toward either field have a passion, or a “calling” that allows them to engage in medically-complicated and emotionally-complex patient care. Furthermore, both provide a highly individualized approach to care; one based on disease risk factors and molecular markers, and the other on specific symptoms and psychosocial features. Neither field is able to treat a patient in complete isolation without assessing the whole person and considering the available resources, support, and ability to cope. Both also rely on a multidisciplinary care model that draws on the strengths of non-physician colleagues including nurses, social workers, pharmacists, case managers, and spiritual counselors. Despite the support of these multidisciplinary teams, both of these fields share high rates of moral distress and burnout.4-7 Consequently, we strongly believe that there is much that we can learn from each other, and even more that we can do to support the success of one another.

On the bridge: a transplanter's perspective

SCT physicians care for a unique patient population in which the treatment is often complex and the potential complications numerous. The goal is curing a malignancy with a poor prognosis by undergoing a risky procedure. There often seems to be a mystique about the world of SCT. However, the actual SCT (ie, administering a preparative regimen followed by infusion of stem cells) is often times quite uneventful. The challenge lies in managing the potential complications and symptoms that ensue. Complications such as graft versus host disease (GVHD), organ toxicity, and infections can be life threatening and are not typical of solid oncology patients. Thus, transplanters are very cognizant of the role of optimal supportive care that includes managing the side effects of treatment, transfusions, prophylactic antibiotics, and treatment of infections.

PC is a part of optimal supportive care. The World Health Organization (WHO) defines PC as “an approach that improves the quality of life of patients and their families facing the problems associated with life-threatening illness, through the prevention and relief of suffering by means of early identification and impeccable assessment and treatment of pain and other problems, physical, psychosocial and spiritual.” The WHO further clarifies that PC “…offers a support system to help patients live as actively as possible until death; [and …] is applicable early in the course of illness, in conjunction with other therapies that are intended to prolong life, such as chemotherapy or radiation therapy, and includes those investigations needed to better understand and manage distressing clinical complications.”8

Based on this definition, we highly doubt that transplanters would oppose PC. So why does there exist this belief that PC and SCT have opposing goals? One possible reason is perspective. Given the usual context and timing in which PC providers evaluate SCT patients, PC providers view of SCT is skewed to the patients doing poorly with problems, such as steroid refractory GVHD, organ failure, and severe infections in which a shortened life expectancy is no surprise. The conversation at this juncture then typically revolves around “addressing goals of care” in a way that usually means a transition toward a focus on symptom palliation without escalating care. From the transplanter's (and perhaps patient's) perspective, it may then appear that PC's role is limited to transitioning to comfort care. An interesting approach to consider is whether earlier PC involvement would change these perceptions.

Perhaps PC could also serve a role in the post-transplant setting in which patients are doing well from the malignancy perspective, but struggling with the after effects of treatment. Some SCT-related complications that occur, such as GVHD, can have devastating effects on quality of life. Yet in some of these same patients, they are cured of their potentially lethal malignancy. So how do we balance the trade off in which life may be prolonged and cancer cured, but quality of life is poor? Was the transplant worth it? In this setting, the patient may be struggling not just with the physical problems, but also psychosocial problems of being a transplant survivor. It is not a far leap to see how PC could provide a beneficial service to this patient population as well.

On the bridge: a palliator's perspective

In a published, two-part article series, we reviewed the unique culture, physical symptoms, and psychosocial issues in SCT for our PC colleagues.9,10 Now, it is important to clarify to SCT clinicians what PC is and is not. Many misconceptions taint how SCT clinicians view PC. For example, although pain is a frequent reason for PC consultation, PC is not solely a pain management team. More importantly, PC includes but is not synonymous with end-of-life care or hospice care. PC is also not limited to comfort care. Yet many blood cancer specialists view PC as just late-stage care, end-of-life care, or hospice.11

For PC to be used appropriately in the SCT setting, clinicians and patients must understand the fundamental differences between PC and hospice care. The Medicare hospice benefit provides hospice care exclusively to patients who choose to forgo curative treatments and who have a physician-estimated life expectancy of 6 months or less.12 In contrast, PC is not limited by a physician's estimate of prognosis, or a patient's preference for curative medications or procedures. PC is specialized medical care “appropriate at any age and at any stage in a serious illness and can be provided along with curative treatment.”13 Thus, PC should be available from the time of diagnosis until it is no longer needed.

The PC team specializes in whole person assessment, symptom management, and advance care planning communication. By definition, PC is a multidisciplinary team consisting of physicians, nurses, social workers, pharmacists, and spiritual counselors who practice under established national quality guidelines.14 Each team member provides unique expertise in the evaluation and care of patients with advanced illness and high symptom burden. Unfortunately, in the traditional medical funding model, social workers and spiritual counselors frequently cannot be supported because they typically do not bill and therefore may have a limited role. Moreover, although dedicated PC training exists for physicians,15 nurses,16 social workers,17 and spiritual counselors,18 not all PC clinicians have completed formal training. For example, practicing physicians may or may not have completed a formal 1-year Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education-accredited hospice and palliative medicine fellowship program and/or be board certified.15

PC has particular relevance in oncology given recent studies that link PC to improved patient quality of life, improved survival in patients with metastatic cancer, and decreased cost of care.19-26 The most recognized of these studies was a randomized, single-institution clinical trial conducted by Temel et al in advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC).21 In this study, newly diagnosed metastatic NSCLC patients who were randomized to receive early PC integrated with standard oncology care versus standard oncology care alone experienced improved quality of life, lower rates of depression, and lived 2.7-months longer.21 In this setting, this increase in overall survival rivals that observed with cytotoxic chemotherapy: 2 months for bevacizumab when added to carboplatin/paclitaxel and 2.6 months for maintenance pemetrexed.27,28 This prolonged survival trend was also observed in the Project Enable III randomized controlled trial in advanced cancer patients. Those patients who received early PC had a median survival of 18.3 months versus 11.8 months for delayed PC.23 If PC was a drug, it would readily be Food and Drug Administration approved, and it would be a financial blockbuster. More importantly, no study to date has shown harm or increased cost with the integration of PC into standard oncology care. Consequently, current American Society of Clinical Oncology guidelines recommend early combined integration of PC with standard oncology care for any cancer patient with metastatic disease or high symptom burden.29

Building materials are currently limited

Nationwide, PC is still a limited resource despite recent growth. In 2012, 63% of hospitals with 50 beds or more reported having a PC team and these teams served an estimated 6 million patients.30 Over the last decade, the number of hospitals with PC teams has nearly tripled due to the increase in absolute number of programs and the ability to care for a greater number of people living with serious illness. Despite this unprecedented growth, the percent of annual hospital admissions evaluated by a PC team remains low with only 4% of hospital admissions cared for by PC specialists.30 Furthermore, access to PC varies considerably by region and hospital type and size. For example, in the Northeast, 73% of hospitals with 50 or more beds report a PC team compared to only 51% in the South.30 Among hospitals in the South with fewer than 50 beds, access to PC is extremely limited with only 14% having access to PC services.30 Large hospitals with 300 or more beds are more likely to report a PC team (85%); in contrast, public hospitals (54%), for-profit hospitals (26%), and sole community provider hospitals (37%) have limited access.30

Furthermore, there are different levels of PC and it is critical to understand the difference between primary PC and specialty PC.31,32 Primary PC includes basic management of pain and symptoms, depression and anxiety, and discussions regarding prognosis, goals of treatment, suffering, and advance care planning provided by any healthcare provider.32 Through basic education and training, most medical clinicians should learn and use these skills. Primary PC should be provided by primary care and disease-oriented specialists who have not had formal PC training. In contrast, specialty PC requires the management of refractory pain or other physical symptoms, complex psychosocial symptoms (eg, depression, anxiety, grief, and existential distress), assistance with conflict resolution regarding goals or methods of treatment, and assistance in addressing cases of non-beneficial care.31,32 For example, specialty PC would include the use of intravenous lidocaine to palliate refractory neuropathic cancer pain. Another example, specialty PC would address goals of care with a patient in conflict with his/her selected decision makers or who lacks a social support system.

In SCT, we believe the role of PC and its integration requires a third level of PC—subspecialty PC (also referred to as disease-specific PC).3 Subspecialty PC is highly specialized PC provided and integrated in specific medical contexts addressing disease and treatment-specific symptoms, complications, and related psychosocial issues. Ideally, we believe at least one of the medical clinicians of the PC team (ie, oncologist, nurse practitioner, or nurse) needs to have specific SCT training, knowledge, and/or experience to lead and facilitate a successful integration. Lasting integration must come from within the SCT community. As of 2014, 238 hospice and palliative medicine board-certified physicians were also board certified in combined hematology and oncology, another 18 in hematology, and another 226 in oncology (American Board of Internal Medicine, personal communication, April 29, 2015). Although the total 482 physicians with dual training and board certification cannot possibly meet the demand across the nearly 200 accredited transplant services across the United States,33 they can lead, educate, and inspire others in pursing this training and integration.

One bridge: the UCSD experience

In 2005, Dr Charles von Gunten, a dual-trained PC oncologist and nationally recognized PC leader, founded the Doris A. Howell Palliative Care Service at the University of California, San Diego (UCSD). Given his training and experience in oncology, he decided to focus initial efforts of PC integration specifically on inpatient SCT patients, given their high-symptom burden and their geographically distinct unit in the hospital. With the support of the UCSD SCT service, Dr von Gunten and a PC fellow started evaluating patients on the SCT unit in October 2005; a nurse practitioner joined the service in January 2006. The PC clinicians were present for daily inpatient SCT rounds with an average census of 35 patients. When issues arose regarding optimal symptom management or addressing complex psychosocial issues, the PC provider was readily available to see the patient and make recommendations. Excluding donor lymphocyte infusions, 113 transplants were performed in 2005, and 113 in 2006 (Table 2). In the initial 6 months of the PC service, 136 encounters were completed on SCT patients and there were 65 SCTs at UCSD during that time interval. Given limitations of collecting data from an antiquated paper chart system, we approximate that more than one-half of the patients on the inpatient SCT service received at least one PC visit during the initial 6 months.

Now, 10 years later, we have an established and growing inpatient and outpatient PC service consisting of six PC board-certified physicians (3 family medicine, 2 oncologists, and 1 psychiatrist), 4 nurse practitioners, 1 registered nurse, 2 licensed clinical social workers, and 2 pharmacists. In 2013, there were 136 SCTs and 447 PC encounters specifically in hematologic malignancies; in 2014, 143 SCT and 585 PC encounters were completed in the same population (Table 2). Symptom management continues to be the most common reason for PC consultation. In 2014, with the addition of a PC psychiatrist to our team, we have also seen an increase of specific consults for anxiety and depression (n = 144 encounters, 24%).

Over the course of the last decade, many lessons have been learned. The PC team has gained enormous respect for our SCT colleagues based on the understanding that SCT is intense and meaningful work resulting in very close relationships between SCT clinicians and their patients. These relationships are further intensified compared to the doctor–patient relationships in solid tumor cancers given the amount of time patients spend on the inpatient service and in close follow-up as outpatients. As a result, very tight bonds are forged among patients, caregivers, and the SCT team. However, it is because of these intense relationships and the passionate focus on curing patients that it is difficult to address all complications and toxicities. Simultaneously, SCT patients may under-report their symptoms for fear it may lead to less aggressive treatment or may disappoint their SCT team or their loved ones. This results in a relationship where remaining objective may be compromised. As has been demonstrated with physicians' ability to prognosticate,34 the longer the relationship between provider and patient, the less objective we become. As in the Temel study,21 we believe this highlights the need for a separate PC provider to address symptoms and goals of care given the ongoing relationship with the SCT team.

We have also observed that, like most tight-knit teams, SCT clinicians work very closely together and it can therefore take time to develop an effective working relationship with new people. It is crucial that new PC clinicians earn the respect and trust of the SCT team by demonstrating that they understand the purpose or process of transplant and at the same time provide clinically-meaningful assessments, recommendations, and availability. Case in point, we have observed that the 2 trusted PC oncologists who trained at the institution are initially requested; whereas, the unfamiliar PC clinicians are more slowly accepted only after time and effective collaboration has been established.

Overall, addressing palliation takes a lower priority for the SCT team who are focused on acute life-threatening complications of transplant. Notably, when PC consultations do occur, they tend to be very late in the course of the disease, thus supporting the misconceptions that PC is equivalent to comfort care, end-of-life care, or hospice care. In contrast, PC should be considered as an added layer of support for the SCT team and therefore implemented as a standard supportive measure early in the course of illness.

Crossing the canyon

Recognizing the many challenges of integrating PC with SCT at our and other institutions,35 we believe we need to direct future collaborative opportunities in the following areas: addressing prognostic and treatment-related risk understanding, evaluating and supporting nonphysical suffering, establishing expectations of effective PC expertise in SCT, and establishing routine PC integration at time of diagnosis.

One major challenge in the SCT process is the concept of informed consent. Despite herculean efforts by the SCT team to inform and educate patients regarding SCT risks prior to transplant, patients and caregivers often do not hear the information because they are focused on life and death. In this emotionally-charged setting, patients and loved ones cannot assimilate information and frequently choose to believe they are the exception to the statistics. Therefore, when treatment-related complications or poor outcomes occur, patients and loved ones frequently are surprised and desperate. Having a separate PC team help patients and loved ones understand the prognostic and treatment-related risks from the time of diagnosis throughout the course of illness, may achieve synergy with the SCT team.

SCT patients also experience poorly controlled symptoms and therefore suffer. We believe suffering should not be viewed as inevitable (ie, “no pain, no gain”). It is important to recognize that suffering goes beyond physical symptoms. In the medical setting, effectively palliating physical symptoms is usually the focus, but should be expanded to assessing and managing psychological, social, and spiritual issues. In practice, these dimensions are not easily distinguished; the division between physical and psychological symptoms is often blurred, and physical symptoms are interrelated with emotional status and social support.10 Sometimes SCT patients are upset because their illness is upsetting, not because anyone did anything wrong. This is normal. We should allow patients to emote without pretending that everything is going to be fine or placing blame on others.

Additionally, the PC team should further support the SCT team in the psychosocial evaluation, which may be the most difficult aspect of the pre-transplant assessment in the medical setting. SCT social workers do the best they can given the pressure to quickly perform a comprehensive psychosocial assessment (eg, history pertaining to the patient, family, education, work, finances, insurance, disability, spiritual practices, functional status, tobacco/drugs/alcohol, coping, understanding of medical status and treatment plan, support network, post-transplant care, and advance care planning)36 and not delay a potentially curative transplant. The PC team could provide additional spiritual and psychosocial support to the patient and family facing the uncertainties of transplant.

PC teams must respect and understand the SCT process and step up to the challenge of effectively coordinating care and providing clinically-meaningful assistance to patients, caregivers, and colleagues. Daily engagement and face-to-face interactions are key to effective collaboration. Supporting the SCT team is as much of the PC role as supporting the patient and caregiver. Given the workload and dynamic science of transplantation, SCT clinicians need support and there is a clear role for a non-SCT provider to assist in the care of these patients. PC needs to recognize that within the day-to-day harried work of SCT, there is little room for grief and bereavement, and there is a need to support our SCT colleagues who frequently experience compassion fatigue. Additionally, PC needs to support its SCT colleagues in delivering bad news. It is a skill that requires practice and there are SCT clinicians with varying levels of comfort in delivering bad news.

Hematologic malignancies are unique and present their own challenges to PC integration. For example, hematologic malignancies appear to be more curable in advanced stages which makes predicting the course of events difficult; as a result, the observed decline can occur very rapidly thereby narrowing the window of opportunity for PC integration.3 Rather than wait for this fleeting window to appear, PC should challenge the existing norm and advocate for integration at time of diagnosis and based on need, not prognosis (Figure 1B). PC should have an established voice in the pre-transplant setting, as an added layer of support. Although PC should be integrated across all SCT, given the challenge of PC access, we also need to be pragmatic. One possible first step toward effective integration could be for those patients at highest risk of poor outcomes, such as second allogeneic SCT, first allogeneic SCT following relapse after an autologous SCT, acute leukemia not in remission, hematopoietic cell transplant comorbidity index (HCTI) >4,37 and complicated psychosocial factors. Interestingly, early PC assessment and integration is not a new standard in accreditation of programs caring for medically-complex patients and currently is a requirement for the Joint Commission advanced certification of left ventricular device programs.38 Within SCT, PC pre-transplant assessment would ensure that relationships are established among the patients, caregivers, and SCT team promoting effective coordination of care.

Building a lasting bridge

Future directions must focus on the similarities and not the differences between SCT and PC. Collaboration should focus on developing effective strategies to support patients and caregivers across the continuum of care. However, we must recognize that the data about improved quality of life, survival, and health care-related costs in patients with advanced solid tumor malignancies may not be extrapolated to hematologic malignancies and SCT. We acknowledge the paucity of data and eagerly anticipate the results of the ongoing study evaluating early integration of PC in SCT on patient and caregiver quality of life, mood, 1-year overall survival, and non-relapse mortality by Dr El-Jawahri and colleagues (NCT02207322).39 We should expand our evaluation of the impact of PC on quality of life in SCT with the hypothesis that early PC integration and optimal palliation will lead to fewer dose reductions/delays, will decrease complications, and will shorten the hospital length of stay. Subsequently, the key toward building an effective integration between SCT and PC will require the following steps: (1) education for clinicians, patients, and caregivers regarding what PC is and is not; (2) leadership and guidance by PC oncologists trained in SCT in effective and meaningful ways to integrate; (3) prospective studies evaluating the early, simultaneous integration of PC in SCT; and (4) standard PC assessment in the pre-transplant assessment. A key first step for early integration should occur in an area of low-hanging fruit, such as early integration in the high-risk SCT setting, especially in PC resource-poor areas. As to how we implement these opportunities, it will require a lasting bridge between SCT and PC that is both strong and flexible.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank and acknowledge our PC and SCT patients, caregivers, and colleagues for inspiring us every day.

Correspondence

Eric Roeland, University of California, San Diego Moores Cancer Center, Oncology & Palliative Care, 3855 Health Sciences Dr, Mail Code 0987, La Jolla, CA 92093; Phone: 858-822-3614; e-mail: eroeland@ucsd.edu.

References

Competing Interests

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Author notes

Off-label drug use: None disclosed.