Abstract

Blood group alloimmunization is “triggered” when a person lacking a particular antigen is exposed to this antigen during transfusion or pregnancy. Although exposure to an antigen is necessary for alloimmunization to occur, it is not alone sufficient. Blood group antigens are diverse in structure, function, and immunogenicity. In addition to red blood cells (RBCs), a recipient of an RBC transfusion is exposed to donor plasma, white blood cells, and platelets; the potential contribution of these elements to RBC alloimmunization remains unclear. Much attention in recent years has been placed on recipient factors that influence RBC alloantibody responses. Danger signals, identified in murine and human studies alike as being risk factors for alloimmunization, may be quite diverse in nature. In addition to exogenous or condition-associated inflammation, autoimmunity is also a risk factor for alloantibody formation. Triggers for alloimmunization in pregnancy are not well-understood beyond the presence of a fetal/maternal bleed. Studies using animal models of pregnancy-induced RBC alloimmunization may provide insight in this regard. A better understanding of alloimmunization triggers and signatures of “responders” and “nonresponders” is needed for prevention strategies to be optimized. A common goal of such strategies is increased transfusion safety and improved pregnancy outcomes.

Learning Objectives

To consider the role of RBC antigen characteristics and blood processing in RBC alloimmunization

To understand the role of recipient genetics and environmental influences in RBC alloimmunization

Introduction

Red blood cell (RBC) alloimmunization, or the formation of antibodies against non–self-antigens on RBCs, may occur after exposure through transfusion or pregnancy. These antibodies may be clinically significant in both settings, leading to delayed hemolytic or serologic transfusion reactions or hemolytic disease of the fetus and newborn (HDFN). As shown in Table 1, the number of alloimmunized transfused patients1 is likely higher than the 1% to 3% commonly quoted, taking into consideration the frequent occurrence of RBC antibody evanescence. Complications from RBC alloantibodies are a leading cause of transfusion-associated death,2 although the true morbidity/mortality burden from RBC alloimmunization is likely higher than that appreciated from the Food and Drug Administration–reported statistics alone.3,4

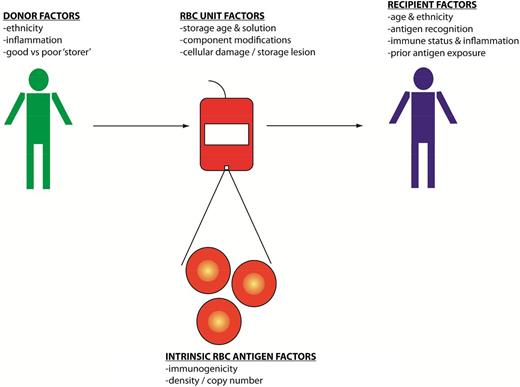

Donor and recipient factors play a role in RBC alloimmunization (Figure 1) and range from characteristics of particular blood group antigens to the recipient’s ability to present the antigens to their immune system. In addition to genetic factors, emerging data emphasize the importance of environmental factors in the formation of RBC alloantibodies. Findings from descriptive human studies have led to the testing of hypotheses using reductionist animal models, and outcomes observed in animal models have been studied in humans. Although antigen avoidance strategies exist to minimize RBC alloimmunization in patients at highest risk for this complication, the genetic or immunologic signature that differentiates a “responder” from a “nonresponder” to RBC antigens remains poorly understood. Despite this lack of understanding, it is hoped that this manuscript will provide insight to readers into some triggers of RBC alloimmunization.

A schematic model of the potential triggers for blood group alloimmunization including donor, recipient, unit, and RBC-specific factors that may influence the development of alloantibodies.

A schematic model of the potential triggers for blood group alloimmunization including donor, recipient, unit, and RBC-specific factors that may influence the development of alloantibodies.

Antigen considerations

One factor that makes human studies of RBC alloimmunization so difficult is the large number and structural diversity of blood group antigens. Hundreds of blood group antigens have been described to date, such that a 1 “unit” of an RBC transfusion may contain many antigens that are foreign to the transfusion recipient. Some of these antigens differ by a single amino acid polymorphism from the antithetic antigen expressed on the recipient’s own RBCs (eg, K vs k), and others are entirely foreign to the transfusion recipient (eg, rhesus D [RhD]). Some blood group antigens are proteins and others are carbohydrates; some antigens are expressed solely on RBCs, whereas others are also expressed on organs or tissues. In rare instances, patients may express an antigen elsewhere in their body but not on their RBCs, as is observed with the Fy antigen in patients with a GATA-box silencing mutation. Given blood group antigen expression on some organs, RBC alloantibodies may be clinically relevant not only in transfusion or pregnancy settings, but also in transplant settings. For example, recipient alloantibodies against Jk antigens have been described to impact the outcomes of transplanted kidneys from Jk-positive donors.5,6

RBC phenotyping, or the evaluation of antigen expression on RBCs using serologic methodology, has historically been used to characterize a particular donor or recipient’s blood group antigen status. However, recent advances in molecular medicine have led to genotyping, or the evaluation of predicted RBC antigen expression using DNA extracted from white blood cells (WBCs), becoming more widely available. Used primarily by blood donor centers and immunohematology reference laboratories, genotyping allows for a more exact prediction of alloimmunization risks in certain circumstances. For example, approximately 30% of patients with hemoglobinopathies that serologically phenotype as C positive actually have C variants as detected by genotyping. These C-variant patients are at risk for alloimmunization to the C antigen if they are transfused with RBCs from donors whose RBCs express a normal C antigen.

The importance of wild-type or variant antigen status ultimately ties into the concept of immunogenicity (ie, how likely an antigen-negative individual is to mount an immune response to an antigen-positive exposure). In the transfusion setting, immunogenicity can be empirically determined by exposing donors to antigens that they lack and then measuring the percentage that develop an antibody response.7 Because this is a laborious (and risky) undertaking, most antigen immunogenicity calculations are estimates based on the number of individuals in a population producing an alloimmune response to a given antigen and their probability of exposure to that antigen based on the frequency with which it is seen in the donor population. Previous studies have shown marked variability in the “potency” of clinically significant blood group antigens, with up to 30-fold differences noted between some of the highest (K, E, Jka) and lowest (S) immunogenicity antigens.8

Blood group antigens differ not only in structure and function, but also in antigen density. RhD is the best example of such differences in humans. RBCs from donors that express an RhD antigen or a “partial” D antigen may sensitize an RhD-negative recipient to the RhD antigen. However, RBCs from donors that express the “weak” D antigen (eg, the same antigen as that seen in RhD donors, but at a low antigen density, particularly those with weak D types 1, 2, or 3) are unlikely to sensitize an RhD-negative recipient to the RhD antigen. This latter fact has led the American Association of Blood Banks, College of American Pathologists, American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, and several other agencies to encourage RhD genotyping to categorize women of childbearing age with RhD phenotyping suggestive of a possible weak D. If these women genotype as weak D types 1, 2, or 3, they are not treated with Rh immune globulin (RhIg) during pregnancy and they are able to safely be transfused with RBCs from RhD-positive donors. In addition to RhD, variations in antigen density are observed in donors homozygous or heterozygous for a particular blood group antigen.

Serologists use screening RBCs with the highest antigen copy numbers to identify the specificity of a particular recipient alloantibody. However, few studies have directly investigated the role in humans that antigen copy number plays in the immunogenicity of non-RhD antigens. Animal studies allow for single variables, such as antigen copy number, to be investigated, with copy number recently being hypothesized to play an important role in immune responses to transfused transgenic murine RBCs expressing the human KEL glycoprotein. Recipients transfused with RBCs from donors expressing a KEL at a very low copy number (“weak” KEL) fail to generate anti-KEL glycoprotein alloantibodies. In contrast, recipients transfused with RBCs expressing the KEL antigen at a more moderate copy number have been shown to generate anti-KEL alloantibodies after a single transfusion.9

Blood collection, processing, modification, and storage considerations

As with blood group antigen diversity, there are also a large number of variables involved in blood collection, processing, modification, and storage that may, at least theoretically, impact the immunogenicity of a particular unit. Screening questionnaires eliminate several potentially infectious donors, but a donor that is not feeling well at the time of donation may inadvertently donate not only RBCs, but also transmissible inflammatory cytokines or other soluble factors. In addition, each bag of blood collected from a donor contains not only anticoagulant preservative solution, but also plasma, platelets, and WBCs. Filter leukoreduction, which removes the vast majority of donor WBCs and is accepted to decrease febrile transfusion reactions, human leukocyte antigen (HLA) alloimmunization, and the transmission of some viruses, has been shown in some but not all human10,11 and murine12 studies to decrease the rate or magnitude of RBC alloantibody responses. However, hundreds of thousands of WBCs may still be present in a leukoreduced RBC unit, and leukoreduction filters also have different degrees of efficiency of platelet reduction. Thus, even in a leukoreduced unit, residual WBCs, platelets, or their breakdown products including pro-inflammatory cytokines, microparticles,13 or damage-associated molecular patterns14 may have the potential to impact the recipient’s immune response to the transfused RBC antigens. Further, the timing of processing may impact the number of WBCs, cytokines, and microparticles in the bag, with units processed after an overnight hold being reported to have more potentially biologically active contaminants than those processed soon after collection.13,15 Reductionist studies of the impact of many of these elements on RBC alloimmunization in humans are logistically difficult, given the number of other involved variables.

Over the past decade, there has been much interest in the impact of RBC storage duration on patient outcomes. These studies, reviewed elsewhere, have focused primarily on mortality and outcomes such as length of intensive care unit stay; few prospective studies of RBC storage duration have included RBC alloimmunization as an outcome measure. The human studies that have investigated this issue have largely concluded that storage duration does not impact alloimmunization,16-18 although at least 1 study has shown human RBCs of greater storage duration are more readily phagocytosed using an in vitro assay19 ; another study has shown a relationship between storage age and alloimmunization in the setting of sickle cell disease.20 Reductionist murine studies have also shown increased phagocytosis of stored compared with fresh RBCs,21 along with increased rates/magnitudes of alloimmunization for some but not all RBC antigens.12 Differences are observed in storage characteristics from donor to donor,22 however, with storage duration being just one variable to consider.

Recipient genetic status

Exposure to a nonself blood group antigen is, for all practical purposes, a requirement for a recipient to generate an alloantibody. However, exposure alone is not sufficient to lead to alloimmunization, or else every transfusion recipient would be highly alloimmunized. The ability to present a particular RBC antigen on a recipient HLA is a requirement for antigens that are dependent on T-cell help. Studies in the area of neonatal alloimmune thrombocytopenia are an example of how the ability to present an antigen (in that case, human glycoprotein 1a) is required but not alone sufficient for an anti-human glycoprotein 1a alloantibody response.23 It is assumed that the majority of clinically significant human RBC antigens are T-cell dependent, though few studies exist. Antigens such as RhD are large and diverse enough that virtually any recipient HLA is thought capable of presenting a portion of the antigen, whereas other antigens such as Fya24 and K25 have been shown to have more restricted HLA presentation. In addition to HLA restriction studies, a recent population based study has suggested that HLA-DRB1*15 may predispose transfused recipients to the formation of multiple different RBC alloantibodies.26

In addition to HLA differences, there are a multitude of genetic variants in recipient immunoregulatory genes that may, in theory, impact RBC alloimmune responses. Polymorphisms in TRIM 21 (Ro52)27 and CD8128 have been implicated in recipient alloimmune responses in humans. Few genome-wide association studies have been completed in RBC alloantibody responders and nonresponders, and no large effect responder loci have been described to date.29

Other recipient considerations, including immune status, disease state, and environment

Although genetic predisposition to alloimmunization is likely quite important, several emerging studies in animal models and humans alike have highlighted the relevance of a “danger signal” in the formation of RBC alloantibodies. This danger signal may be in the form of exogenous Toll-like receptor agonists such as polyinosinic-polycytidylic or 5′-C-phosphate-G-3′ administered to transfusion recipients in murine models,12 with these agonists turning nonresponders into responders in some models, or increasing the magnitude of the immune response in other models. Transfusion in the presence of a danger signal like polyinosinic-polycytidylic acid is known to increase consumption of RBCs by recipient dendritic cells and to increase costimulatory signals on antigen-presenting cells.30 Further, depletion of dendritic cells in general, and an absence of functional bridging channel dendritic cells in particular, abrogates alloantibody responses to stored RBCs in at least 1 murine model.31

Studies in humans have found that patients with sickle cell disease transfused during acute illness (such as acute chest syndrome or vasoocclusive crisis) are more likely to become alloimmunized than patients transfused in their baseline state of health.32 In addition, patients with inflammatory bowel disease,33 other inflammatory disorders,34 or chronic autoimmune diseases35 have been described to have higher rates of alloimmunization than control patients. On the other hand, patients receiving immunosuppressive medications have been described to have lower rates of alloimmunization than control patients.36

Patients with sickle cell disease and thalassemia have among the highest rates of RBC alloimmunization of all transfused patient populations. Antigenic variants in donors and recipients likely account for some degree of alloantibody formation,37 though other variables may also be involved. However, vascular abnormalities, inflammation, and immune dysregulation may also play a contributing role. Further, in keeping with the theory that “responders” are distinct in some way from “nonresponders,” RBC alloimmunization has been associated with the formation of HLA alloantibodies in patients with sickle cell disease receiving solely leukoreduced blood products.38 Antigen avoidance is the primary strategy taken at the present time to minimize alloimmunization in these patient populations. However, alloantibody formation continues to occur in some patients despite phenotype-matched transfusions and may complicate future transfusion, transplantation, and pregnancy.

Prior antigen exposure in the recipient

Past exposure to blood group antigens may, in theory, either prime a transfusion recipient for a rapid anamnestic antibody response, result in ignorance, or lead to tolerance. Anamnestic responses as well as tolerance have been shown to occur in murine models, with donor antigen characteristics and recipient inflammatory status playing a role in determining whether responsiveness or tolerance results following RBC transfusion.9,39 Although tolerance per se has not been shown in human studies, nonresponsiveness has been suggested in patients with thalassemia or sickle cell disease that were initially exposed to RBCs at a relatively young age. The possibility of inducing sustained nonresponsiveness or even tolerance in patients with diseases requiring a large lifetime transfusion burden is appealing, though intermittent antigen exposure may be required to maintain such nonresponsiveness.

In addition to past RBC exposure, prior contact with non-RBC antigens that possess shared sequences with RBC antigens may impact future responses to transfused RBCs. For example, a number of organisms have linear peptide sequences that overlap with blood group antigen sequences; Haemophilus influenza shares orthology with KEL and Yersinia pestis shares orthology with Fy. This is not just a theoretical concern; it has been demonstrated that peripheral blood mononuclear cells from humans never before exposed to RBCs have evidence of T-cell reactivity upon stimulation with overlapping KEL peptides.25 Similarly, animal studies using a model antigen have shown that exposure to sequences contained in a virus are able to prime a recipient to robustly respond to a transfusion of RBCs containing the shared epitope.40 Of note, an RBC antibody screen completed in a clinical blood bank after virus exposure but before RBC exposure would never detect this prior T-cell “priming.”

Exposure to RBC antigens during pregnancy or delivery

Although this manuscript is primarily focused on potential triggers of RBC alloimmunization during transfusion, a brief discussion of triggers during pregnancy and delivery is warranted. All pregnant women are exposed to fetal RBCs during pregnancy and around the time of delivery. The vast majority of women do not become alloimmunized after this exposure, although a subset do. The immunogenicity of the RBC antigen appears to be one critical factor in whether a woman will become alloimmunized, with the majority of clinically significant HDFN cases being due to antibodies against antigens in the Rh, K, Fy, Jk, and MNS families. ABO incompatibility between mother and fetus plays a protective role against RBC alloimmunization, presumably because of maternal isohemagglutinins rapidly clearing fetal RBCs from the maternal circulation.

In addition to fetal/maternal bleeds, 1 other trigger of RBC alloimmunization in pregnancy is intrauterine transfusion.41 These transfusions are typically given to women in the late second or third trimesters of pregnancy if their fetus shows signs of anemia or hydrops. Given that HDFN is most often secondary to maternal alloimmunization, the pregnant women being transfused have already proven themselves to be “responders” to RBC antigens. Thus, that at least 25% of these women form additional RBC antibodies in response to intrauterine transfusions is not entirely surprising. These women are not only at risk of forming additional RBC alloantibodies, but also of forming HLA alloantibodies.

Reviewed in a past issue of the ASH Education Book,42 a better understanding of the mechanism of action of RhIg may facilitate an understanding of the way in which fetal RBCs expressing the RhD antigen stimulate anti-RhD formation in women. Further, a better understanding of the mechanism of action of RhIg may facilitate the production of a standardized RhIg-like product that is not dependent on immunizing RhD-negative male volunteers with RhD-positive RBCs. In-depth mechanistic studies are logistically difficult to complete in humans; an RhD transgenic mouse has recently been generated and may provide the answers to some of these questions. Studies of strategies to prevent alloantibody formation through pregnancy in other animal models may provide additional insight.

Conclusions

There are many potential triggers of RBC alloimmunization in transfusion and pregnancy settings. Although much has been learned about “responders” and “nonresponders” to RBC antigens over the past few decades, many questions remain (Table 2). Future studies investigating whether a “signature” of a responder exists will be useful in generating strategies to decrease the likelihood of antibody formation; such studies may also allow for the conservation of highly phenotypically/genotypically matched RBC units for patients at highest risk of alloimmunization. Future investigations identifying potential donor characteristics associated with recipient alloimmunization will also be informative, although each RBC unit will remain biologically unique. Serving as an adjunct to human studies, studies in animal models allow mechanistic questions not capable of being tested in humans to be investigated in reductionist, experimental settings. Multidisciplinary, collaborative studies by physicians and scientists, completed at the bench and at the bedside in the years to come, will allow for alloimmunization triggers to be further understood and for transfusion safety to ultimately be improved.

Correspondence

Jeanne E. Hendrickson, Department of Laboratory Medicine, Yale University, 330 Cedar St, Clinic Building 405, PO Box 208035, New Haven, CT 06250-8035; e-mail: jeanne.hendrickson@yale.edu.

References

Competing Interests

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Author notes

Off-label drug use: None disclosed.