Abstract

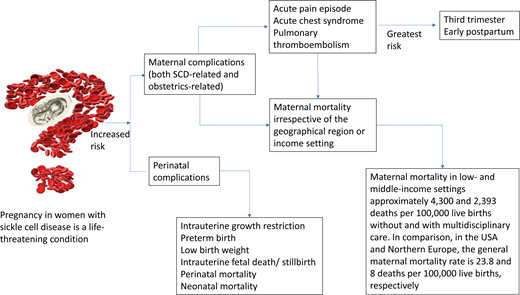

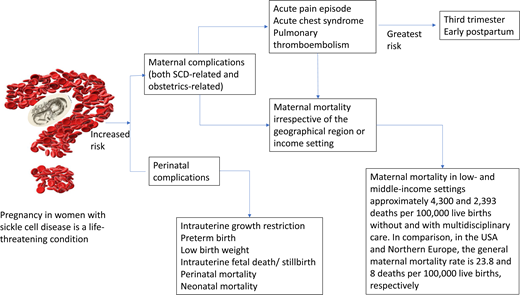

Pregnancy in women with sickle cell disease (SCD) is a life-threatening condition. In both high- and low-income countries, there is an 11-fold increased risk of maternal death and a 4-fold increased risk of perinatal death. We highlight the epidemiology of SCD-specific and obstetric complications commonly seen during pregnancy in SCD and propose definitions for acute pain and acute chest syndrome (ACS) episodes during pregnancy. We conducted a systematic review of the recent obstetric and hematology literature using full research articles published within the last 5 years that reported outcomes in pregnant women with SCD. The prevalence of acute pain episodes during pregnancy ranged between 4% and 75%. The prevalence of ACS episodes during pregnancy ranged between 4% and 13%. The estimated prevalence of pulmonary thromboembolism in women with SCD during pregnancy is approximately 0.5 to 1%. ACS is the most common cause of death and is often preceded by acute pain episodes. The most crucial time to develop these complications in pregnancy is during the third trimester and postpartum period. In a pooled analysis from studies in low- and middle-income settings, maternal death in women with SCD is approximately 2393 and 4300 deaths per 100 000 live births with and without multidisciplinary care, respectively. In comparison, in the US and northern Europe, the general maternal mortality rate is approximately 23.8 and 8 deaths per 100 000 live births, respectively. A multidisciplinary SCD obstetrics care approach reduces maternal and perinatal morbidity and mortality in low- and middle-income countries.

Learning Objectives

Highlight the literature on the epidemiology of obstetric complications (both obstetrics related and SCD related) in pregnant women with sickle cell disease within the last 5 years

Describe the epidemiology of 3 major SCD-related obstetric complications: acute pain episodes, ACS, and PTE

Propose definitions for acute pain episodes and ACS during pregnancy

Highlight the value of a multidisciplinary team (including a hematologist) approach to care as opposed to the tradition of only an obstetrician providing care for a pregnant woman with SCD

CLINICAL CASE

The patient was a 30-year-old woman with SCD (HbSC genotype), para 1, plus 4 spontaneous abortions and 1 intrauterine fetal death (IUFD). She was diagnosed with SCD during childhood and was a regular attendant at the adult sickle cell clinic. Her steady-state hemoglobin level was 11 g/dL, and her baseline hemoglobin oxygen saturation (SpO2) was 98% on room air. A baseline blood pressure reading was 110/60 mmHg. Her last clinic visit was a week prior to the start of her antenatal visit.

SCD complications: On average she experienced 1 acute pain episode per year, had no history of acute chest syndrome (ACS) or venous thromboembolism (VTE), and had no previous blood transfusions or any other chronic complications related to SCD. She did not remember when she last had an acute pain episode prior to pregnancy. She had never been offered and never had any disease- modifying therapy for SCD.

Obstetric history: Menarche was at 13 years of age, and she had a regular monthly cycle lasting 3 days. She and her partner (HbAA) had been trying to have children for the past 5 years and had never been on contraceptives. She had a history of recurrent spontaneous abortions at 14, 16, 17, and 18 weeks' gestation and a sudden IUFD at 30 weeks' gestation. All these pregnancies were managed in a teaching/academic hospital by a multidisciplinary team. Antiphospholipid syndrome screening was negative.

Index pregnancy: She was first seen at the antenatal clinic at a teaching hospital, where she was a regular antenatal attendant from 10 weeks' gestation until 6 weeks postpartum.

Drug history: Oral soluble aspirin, 150 mg daily (from 12 weeks' gestation to prevent preeclampsia), hematenics.

Anomaly scan: Normal.

Last obstetric scan: 36 weeks' gestation; viable single intrauterine fetus; 2.1 kg; breech presentation (longitudinal lie).

Complications in index pregnancy: She was admitted twice for acute pain episodes. The first acute pain episode, precipitated by a urinary tract infection, occurred at 27 weeks' gestation, and it resolved after 1 week with no complications.

The second acute pain episode occurred at 32 weeks' gestation. Despite incentive spirometry with 10 breaths every 2 hours, she developed ACS 3 days after the start of the acute pain episode and was managed on the obstetrics ward for 2 weeks before being discharged home well enough to continue her antenatal visit on an outpatient basis. During both admissions, she received thromboprophylaxis with low-molecular- weight heparin (LMWH).

Labor and delivery: She had a planned delivery (an elective cesarean) at 37 weeks' gestation on account of (1) breech presentation, (2) intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR), and (3) a history of recurrent acute pain episodes and ACS requiring prolonged hospital admission. Blood loss was 400 mL.

The baby weighed 2.2 kg and was transferred from the labor ward to the neonatal intensive care unit after delivery on account of the IUGR. The mother's vital signs (including SpO2 on room air) were normal intrapartum compared to baseline. Immediately after delivery, her vital signs (including SpO2 on room air) were normal compared to baseline, with Hb levels of 10.0 g/dL. She was restarted on prophylactic doses of LMWH and incentive spirometry, as well as adequate analgesia (including opioids) and hydration as part of the standard of care protocol.

Two days after delivery, she had an acute pain episode involving the arms. Three days later, she developed severe respiratory symptoms with hypoxemia (SpO2, 88% on room air), which was managed clinically as ACS. Her condition did not improve while on the ward, and a day later, she was transferred to the intensive care unit. There, a CT pulmonary angiogram confirmed she had a pulmonary thromboembolism (PTE), and she was managed with mechanical ventilatory support, therapeutic doses of LMWH, antibiotics, analgesics, and hydration by a multidisciplinary SCD obstetrics (SCOB) team for 2 weeks.

Both mother and baby were discharged home well 3 weeks after delivery.

Six weeks postpartum: Both mother and baby were well on review. The mother's Hb level was 10.3 g/dL, her blood pressure was 112/66 mmHg, and her SpO2 was 97% on room air. She was discharged to continue care at the adult sickle cell clinic.

Prevalence of obstetric complications in women with sickle cell disease within the last five years

Pregnant women with sickle cell disease (SCD) have an increased risk of SCD-related and obstetrics-related morbidity and mortality regardless of geographical location or income setting.1 Typical physiological adaptations during pregnancy, such as chronic anemia, impaired splenic function, and a hypercoagulable state, predispose mothers with SCD and their fetuses to life-threatening complications. There is an 11-fold increased risk of maternal death and a 4-fold increased risk of perinatal death in both high- and low-income countries.1 While pregnancy rates in individuals living with SCD are increasing, there are still knowledge gaps about the prevalence/incidence of some pregnancy outcomes (primarily due to underreporting and heterogeneity in the definitions of outcomes) and links between clinical risk factors and complications.

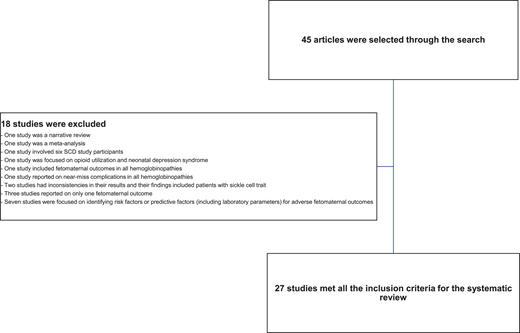

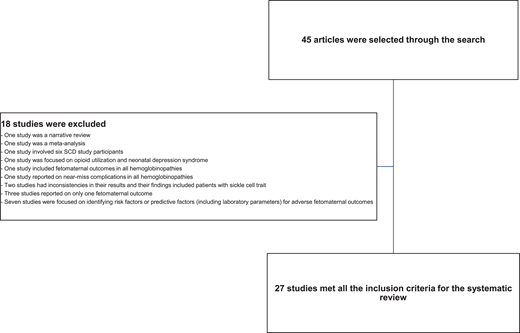

We searched Google Scholar and PubMed (including MEDLINE databases) using medical subject headings for full research articles published in the English language from January 2017 to April 2022 that reported the prevalence of outcomes in pregnant women with SCD. We excluded studies with 6 or fewer SCD participants or reported outcomes in a non-English language. We also excluded meta-analysis studies, narrative reviews, and studies that focused on risk factors or predictive factors (including laboratory markers) for adverse feto-maternal outcomes in SCD. Studies focusing on only 1 feto-maternal outcome and all hemoglobinopathies were excluded (Figure 1). A meta- analysis was conducted comparing maternal and perinatal deaths in low- and middle-income countries with interventional strategies. The meta-analysis was limited to studies in which complete data were reported so mortalities could be compared. Publications were independently screened by 2 reviewers and selected. Data were grouped into maternal or perinatal outcomes and presented in a tabular form.

Criteria used to select the full researched articles used for the systematic review.

Criteria used to select the full researched articles used for the systematic review.

A total of 45 articles were retrieved through the search, but only 27 studies met the selection criteria (Figure 1). Of the 27 articles included in the systematic review, 8 were published from high-income countries while 19 were from low- and middle-income countries. Approximately 70.0% of these articles were retrospective studies, 3.7% were retrospective and prospective studies, and 22.0% were prospective studies.

The clinical case we described earlier had some maternal/SCD-related complications such as acute pain episodes, ACS, PTE, and cesarean delivery. Her perinatal complications included a history of recurrent spontaneous abortion, IUFD, and IUGR, which are prevalent in this cohort.

Tables 1 and 2 summarize the global prevalence of the adverse maternal and perinatal outcomes in women with SCD within the last 5 years. A limitation of note in the published literature of the last 5 years is the absence or nonuniformity in the definition, description, and reporting of outcomes in pregnant women with SCD. Another limitation is that most of the published literature in this high-risk population over the last 5 years are retrospective studies. Countries with a high disease burden (notably sub- Saharan Africa) need to be empowered to undertake more prospective studies focused on maternal-fetal medicine in SCD to highlight and define pregnancy outcomes and their risk factors. The health care system can use this information to plan and evaluate strategies to prevent complications and guide their management in this high-risk cohort.

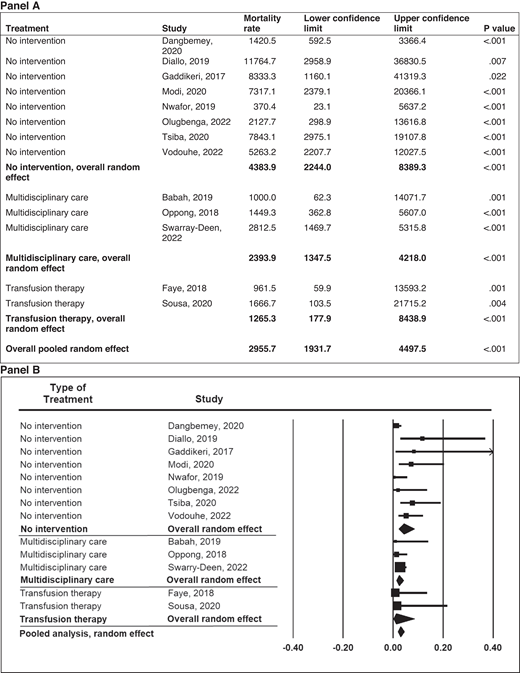

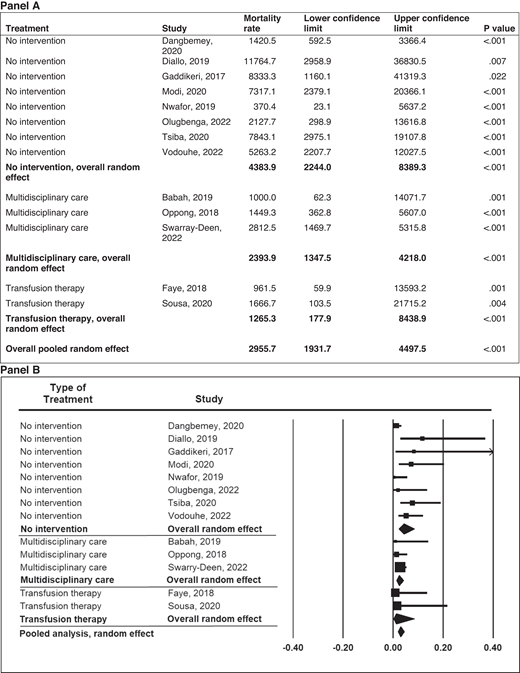

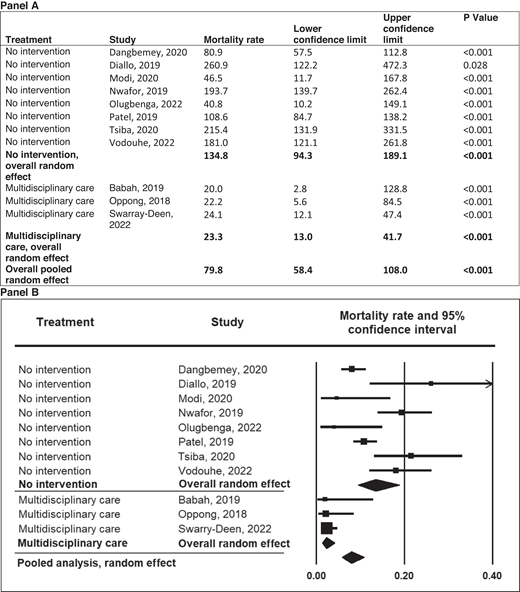

In pregnant women with SCD, there is an 11-fold increased risk of maternal death and a 4-fold increased risk of perinatal death in both high- and low-income countries.1 In low- resource settings, Boafor et al reported a 22-fold increased risk of maternal death in women with SCD compared to pregnant women without SCD in the same setting.1 Limited data exist regarding the risk factors for increased morbidity and mortality and the optimal management of pregnant women with SCD. In our systematic review based on a random-effects model meta-analysis (Q = 16.35; P = .09) of 13 studies conducted in low- and middle-income countries within the last 5 years, a preliminary analysis from observational studies suggests that chronic transfusion therapy from the first trimester to decrease maternal mortality is not superior to the multidisciplinary care approach (P = .271) (Figure 2). However, no definitive therapy exists in the absence of randomized controlled studies comparing the multidisciplinary obstetrics care approach and transfusion therapy to the multidisciplinary obstetrics care approach alone. Again, based on a random-effects model meta-analysis (Q = 31.16; P < .001) with 11 studies conducted in low-income countries, these observational studies suggest that the multidisciplinary care approach is the most efficient and effective method of reducing perinatal mortality (P < .001) (Figure 3).

Meta-analysis of maternal mortality in pregnancies among mothers with SCD in low- and middle-income countries by type of treatment. Mortality rate and 95% CI are displayed per 100 000 live births.

Meta-analysis of maternal mortality in pregnancies among mothers with SCD in low- and middle-income countries by type of treatment. Mortality rate and 95% CI are displayed per 100 000 live births.

Meta-analysis of perinatal mortality in pregnancies among mothers with SCD in low-income countries by type of treatment. Mortality rate and 95% CI are displayed per 1000 total births.

Meta-analysis of perinatal mortality in pregnancies among mothers with SCD in low-income countries by type of treatment. Mortality rate and 95% CI are displayed per 1000 total births.

The clinical case we described had 5 clinically diagnosed acute vaso-occlusive events (3 acute pain and 2 ACS episodes) during the third trimester and early postpartum period and a near-death experience from ACS and PTE. In the subsequent paragraphs, we focus on the epidemiology of 3 significant SCD- related complications linked to mortality in pregnant women with SCD: acute vaso-occlusive events (acute pain and ACS) and PTE.

Acute vaso-occlusive events

Acute vaso-occlusive events in SCD include acute pain episodes and ACS. During pregnancy in SCD, there is an increase in metabolic demand, a hypercoagulable state, and increased red blood cell sickling. Leukocytosis with a predominance of neutrophils is a common physiological adaptation to stress during pregnancy. Compared to nonpregnant women, pregnant women have reduced functional residual capacity, decreased forced vital capacity, and increased inspiratory capacity plus tidal volume.2,3

We postulate that the altered physiology and clinical parameters associated with pregnancy in SCD predispose pregnant women with SCD to an increased risk of acute pain episodes, ACS, and VTE,2,3 particularly in the third trimester.2,4,5 “Vascular occlusion may occur in the placenta, leading to villous fibrosis, necrosis, and infarction, resulting in decreased uteroplacental circulation. Vascular occlusion often manifests as chronic fetal hypoxia, IUGR, and fetal demise.”2

The postpartum period is associated with a high rate of acute vaso-occlusive events (acute pain and ACS) and VTE. Although the physiological and hematological basis for the increased risk of significant complications up to 6 weeks postpartum has not been elucidated, our clinical team considers the first 7 days after delivery to be the period when the patient is most likely to experience complications4,5 ; therefore, we closely monitor this interval. Several factors may play a role in acute vaso- occlusive events during the postpartum period. Those during the immediate postpartum period include fasting with dehydration during labor, maternal fatigue from expulsion of the fetus, intense pain in the absence of epidural or adequate analgesia, and the development of metabolic acidosis because of excessive uterine muscle work and respiratory alkalosis from hyperventilation. Other contributing factors during the postpartum period include immobilization (from suboptimal pain relief, acute illness, or increased fluid retention during pregnancy), maternal fatigue from adjusting to the feeding times/demands of a newborn and increased workload, and inadequate anticoagulation during hospital admission and after delivery.

Generally, it is well known that sickle cell anemia (HbSS) runs a more severe but markedly variable clinical course compared to HbSC disease, which is milder and may be diagnosed in adulthood.6 In Ghana, where there is a high SCD burden, HbSS is more prevalent at birth and adolescence.7 However, due to anecdotal evidence of a high mortality rate in individuals with HbSS, more individuals with HbSC are seen during adulthood,7 and pregnancy is seen more frequently among women with HbSC disease.8,9 Even though pregnant women with HbSS have higher frequencies of obstetric-related and SCD-related morbidities and mortality, findings from the multidisciplinary SCOB study from Ghana and other studies have reported statistically similar obstetric-related and SCD-related outcomes (including acute vaso-occlusive events and mortality) in pregnant women with HbSS or HbSC.4,5,9,10 The care of pregnant women with HbSC, therefore, needs to be managed with the same aggressive multidisciplinary approach as the care of pregnant women with HbSS. Again, findings from the multidisciplinary SCOB study from Ghana have not made any associations between acute vaso-occlusive events and maternal age, parity, and phenotype.5,9 The clinical case we described developed a PTE during the early postpartum period despite adequate anticoagulation, emphasizing the increased risk of VTE during the postpartum period.

Pulmonary thromboembolism

A systematic review and meta-analysis of 22 studies from high-, middle- and low-income countries published in 2019 by Inparaj et al reported the estimated prevalence of PTE in pregnant women with SCD as 105 per 10 000 (95% CI, 65-170), compared to the estimated prevalence of 13.8 per 10 000 (95% CI, 12.5-15.1) in women without SCD during pregnancy.11 In their meta-analysis, there was nearly an 8-fold increased risk of PTE in women with SCD (relative risk, 7.74; 95% CI, 4.65-12.89).11 Two manuscripts published by the multidisciplinary SCOB team from Ghana reported that approximately 25% and 11%, respectively, of the maternal mortalities clinically diagnosed as ACS were due to a massive bilateral pulmonary embolism that was not clinically diagnosed but picked up at autopsy.4,12 These pulmonary thromboembolic episodes occurred during the third trimester and early postpartum period, and all the women had thromboprophylaxis with LMWH.

Considering the risk of PTE associated with pregnant women with SCD, essential research questions are highlighted: Why do they have an increased risk of PTE? When is the appropriate time to start thromboprophylaxis? How long should anticoagulation be given in this cohort?

Pregnant women who present with chest pain and respiratory distress with an unremarkable chest roentgenogram should be suspected of having a pulmonary embolism.2 The clinical case we described had 3 acute pain and 2 ACS episodes. A urinary tract infection provoked the first acute pain episode. Three days after the second and third acute pain episodes, she had ACS as a complication of the acute pain episodes. Before the second ACS episode, she also had a cesarean delivery and treatment with opioids for her postpartum pain.

Malinowski et al reported that in 2016 a working group of pregnancy experts recommended 15 measures for the PhenX Toolkit that are highly relevant to pregnancy research. The working group followed the established PhenX consensus process to recommend well-established, nonproprietary, broadly validated protocols with a relatively low burden for investigators and participants.13 A critical next step is to identify a common language to define acute pain and ACS episodes during pregnancy, considering they are the most common causes of hospitalization in pregnant women with SCD. From Table 1, 23 (85.2%) studies reported on acute pain episodes, while 15 (55.6%) reported on ACS. However, only 4 (14.8%) studies defined acute pain and ACS episodes in their methodology (Table 3).

Acute pain episodes (vaso-occlusive crisis)

In a large teaching hospital in Ghana (a resource-poor setting), the multidisciplinary SCOB team defined an acute vaso-occlusive pain episode in pregnant women with SCD as “acute vaso-occlusive pain, which can be distinguished from labor pain based on the absence of uterine contractions, evidence of labor progression, and delivery and required parenteral or oral opioids.4,5,9 If the patient could judge whether the pain was of the type usually associated with crisis and reported such pain, this was considered appropriate evidence of an acute pain episode” (Table 3).5 This definition provides a good starting point for defining acute pain episodes during pregnancy.

An acute pain episode is the most frequent complication and the most common cause of maternal hospitalization in SCD. The systematic review in Table 1 shows that the prevalence of acute pain episodes during pregnancy in high- and low-resource countries ranged between 4% and 75%. There was little difference when comparing the prevalence of acute pain episodes in high- and low-resource settings.

Factors that can play a role in the frequency of acute vaso-occlusive pain episodes include wet or cold climates and the increased risk of recurrent infections in this cohort.1,7

Serious complications of acute pain episodes such as ACS, multiorgan failure, and sudden death can occur between 1 and 5 days after the start of the acute pain episode.14 A case series from Ghana reported that of the 75% of cases admitted for acute pain episodes, approximately 80% developed ACS as a sequela before death.4 Nearly 87% of the deaths were caused by ACS, with a median hospitalization interval before death of 3.5 days.4 Another recently published manuscript from the same setting reported the prevalence of acute pain episodes among hospitalized pregnant women with SCD as 66.7% during the sustainability period; 83.3% of them developed ACS as a sequela prior to death.12 The median interval of hospitalization prior to death was 5.6 days.12

Despite published literature that acute pain rates in women with SCD are higher during pregnancy,5 no systematic study has been done to confirm or refute whether acute vaso-occlusive pain events occur more frequently during pregnancy compared to after pregnancy. Several studies have reported a higher percentage of acute pain episodes in pregnant women with SCD (Table 1); however, neither study included a period after pregnancy or an assessment of acute pain at home. This research gap forms the basis for our American Society of Hematology Global Research Award (2019-2022), which focuses on prospectively assessing the epidemiology of pain incidence rates in women with SCD from the first trimester of pregnancy to 1 year post delivery. With the evidence that acute pain episodes are more common during the third trimester and postpartum period,2,4,5 daily electronic patient-reported outcome measures are being used to monitor acute SCD pain episodes during the pregnancy period (third trimester to 6 weeks after delivery) compared to the postpartum period (6 to 9 months post delivery). In addition, participants complete pain questionnaires during each clinic and study follow-up visit. Our study's unique design addresses acute pain episodes at home when the new mother is unlikely to leave her breastfeeding newborn to be evaluated. Home monitoring is required to describe the full spectrum of acute pain episodes because most acute pain episodes occur and are managed at home.

Acute chest syndrome

ACS is a heterogeneous acute pulmonary process in children and adults with SCD. ACS is the second most common cause of maternal hospital admissions and the leading cause of mortality in pregnant women with SCD.4,12 A systematic review and meta-analysis of 22 studies from high-, low-, and middle-income countries published in 2019 by Inparaj et al reported a composite estimate of the prevalence of ACS and pneumonia in pregnant women with SCD as 6.46% (95% CI, 4.66-8.25) with no significant difference in the prevalence of ACS/pneumonia between the HbSS and HbSC genotypes (relative risk, 1.42; 95% CI, 0.90-2.23].11

The predisposing factors identified for developing ACS during pregnancy in this high-risk cohort included acute pain episodes (including current management practices),4 a previous pulmonary disease with baseline hypoxemia, and cesarean delivery.2 The management of acute pain episodes in SCD often requires opioid analgesics and sometimes intravenous fluids. Opioid analgesics such as morphine are associated with respiratory depression, cardiogenic pulmonary edema, hypoventilation, and atelectasis.15 These mechanisms, coupled with the fluid overload or pulmonary edema from the excessive use of intravenous fluids, predispose to ACS. Abdominal surgery (including cesarean delivery) also predisposes to ACS. Of the 7 participants who had ACS during the postpartum period from the multidisciplinary SCOB study in Ghana,5 85.7% had cesarean delivery before developing ACS.

Based on the poorly defined definition of ACS in low-middle- income countries and the variability of ACS definitions in high-resource settings, we have recently defined ACS in pregnant women with SCD and in children with sickle cell anemia (HbSS) participating in a randomized controlled trial in Nigeria that applies to those living in a low-resource or high-resource-setting.2,9,16 The centrally adjudicated diagnosis of ACS after the completion of the trial revealed concordant clinical management of ACS for the trial participants at the bedside.16

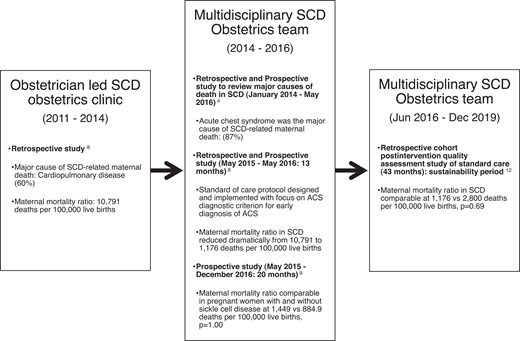

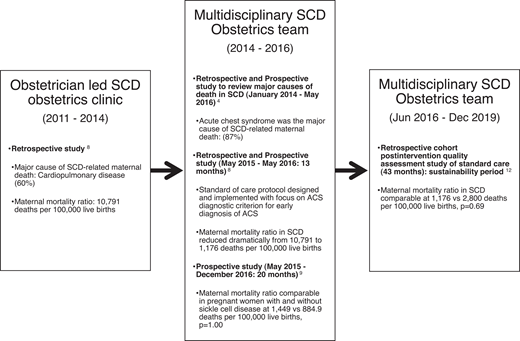

In a large teaching hospital in Ghana (a resource-limited setting), where approximately 150 pregnant women with SCD are seen each year, an obstetrician initiated a clinic for women with SCD in 2011. Cardiopulmonary complications (ACS) contributed to 60% of maternal deaths.8 After observing no significant reduction in the high maternal and perinatal mortality rates after 3 years, in 2014 the SCOB clinic expanded to include a multidisciplinary care team. The multidisciplinary SCOB team sought to elucidate the causes of death in this cohort. A central adjudication process of 43 maternal deaths in women with SCD over 7 years was conducted. ACS, defined in Table 3, was identified as the most common cause of death in approximately 87% of cases, with a majority (80%) of ACS episodes preceded by an acute pain episode. There was no statistical difference in the maternal death rate due to ACS between HbSS and HbSC phenotypes (80% vs 71.4%, respectively; P = .719).4 The multidisciplinary SCOB team created an ACS diagnostic criterion through the central adjudication process. Subsequently, evidence-based strategies for ACS prevention and treatment reduced this cohort's maternal and perinatal mortality ratio by approximately 90% and 60%, respectively.8 This ACS diagnostic criterion (Table 3) was also employed in a prospective study comparing maternal outcomes in 149 women with SCD and 117 without SCD over 20 months.9 In that study, maternal and perinatal mortality rates among women with SCD were reduced to levels comparable to those without SCD.9 Figure 4 describes the impact of the multidisciplinary SCOB team approach to care.

The impact of the multidisciplinary SCD obstetrics team approach to care: the Ghanaian experience.

The impact of the multidisciplinary SCD obstetrics team approach to care: the Ghanaian experience.

Given the importance of both preventing ACS and treating ACS promptly, our multidisciplinary team instituted the following measures that decreased the prevalence of ACS from 43.4 to 0.4 events per 100 patient-years8,9 : (1) routinely using incentive spirometry (10 maximum breaths every 2 hours between 8 am and 10 pm and while awake) or latex-free balloons (with the exact instructions as an incentive spirometer in low-resource countries) for every acute pain episode occurring in the hospital, (2) providing adequate analgesia, (3) identifying and correcting inciting ACS factors, (4) maintaining euvolemia with rigorous fluid monitoring, (5) providing oxygen supplementation to keep SpO2 above 94%, and (6) giving a blood transfusion immediately before or after surgery (when applicable). The well-established evidence-based strategies for ACS prevention postoperatively include a simple transfusion to increase the hemoglobin level to at least 10.0 grams/dL perioperatively and the routine use of incentive spirometry.17

Rapidly progressive ACS is another phenotype of ACS associated with respiratory failure (24 to 48 hours after the onset of respiratory symptoms) and multiorgan failure. Rapidly progressive ACS should be considered a medical emergency in pregnant women with SCD. Its clinical features are like HELLP (hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelet count) syndrome.2 Out of 342 (HbSS, 139; HbSC, 203) pregnancies, 2 women with HbSC disease died from rapidly progressive ACS with multiorgan failure (hepatic dysfunction, coagulopathy), altered mental status, and stroke.12

Conclusion

Pregnant women with SCD have one of the highest mortality rates for any preexisting condition in both resource-low and resource-rich environments. Over 70% of the world's SCD population lives in sub-Saharan Africa. In a pooled analysis from studies in low- and middle-income settings, the maternal death rate in women with SCD is approximately 2393 and 4300 deaths per 100 000 live births with and without multidisciplinary care, respectively. In comparison, the US and northern Europe's general maternal mortality rate is approximately 123.8 and 8 deaths per 100 000 live births, respectively. Cardiopulmonary complications are the leading cause of death, with ACS accounting for over 80% of deaths in pregnant women with SCD. Most vaso-occlusive events (acute pain and ACS episodes) and PTE occur in the third trimester and early postpartum. Substantial evidence in low-resource settings suggests that implementing a multidisciplinary SCOB care approach can help reduce morbidity and mortality. Evidence is lacking that a similar approach reduces mortality and morbidity in high-resource settings. Strong clinical evidence is that multidisciplinary SCOB care reduces maternal and perinatal morbidity and mortality in low- and middle-income countries. Emphasis should be placed on involving a hematologist (preferably the primary hematologist who managed the woman during the prepregnancy period), a neonatologist, and an intensivist/anesthesiologist as care providers during pregnancy and delivery.

Acknowledgments

We thank the multidisciplinary sickle cell obstetrics (SCOB) team at Korle-Bu Teaching Hospital, Ghana, for their immense contribution: John Benaiah Ayete-Nyampong, Alim Swarray-Deen, Yvonne Dei-Adomakoh, William K. Ghunney, Charles Hayfron-Benjamin, Ebenezer Owusu Darkwa, Frederick Oduro, Kwaku Duffour-Dapaah, and Titus Beyuo.

We also appreciate the help from our statistical consultant, Mark Rodeghier, in completing the meta-analysis and acknowledge our multidisciplinary SCOB multisite group in Ghana.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure

Eugenia Vicky Asare: no competing financial interests to declare.

Michael R. DeBaun: no competing financial interests to declare.

Edeghonghon Olayemi: no competing financial interests to declare.

Theodore Boafor: no competing financial interests to declare.

Samuel A. Oppong: no competing financial interests to declare.

Off-label drug use

Eugenia Vicky Asare: nothing to disclose.

Michael R. DeBaun: nothing to disclose.

Edeghonghon Olayemi: nothing to disclose.

Theodore Boafor: nothing to disclose.

Samuel A. Oppong: nothing to disclose.