Abstract

The field of thromboprophylaxis for acutely ill medical patients, including those hospitalized for COVID-19, is rapidly evolving both in the inpatient setting and the immediate post–hospital discharge period. Recent data reveal the importance of incorporating holistic thromboembolic outcomes that encompass both venous thromboembolism (VTE) and arterial thromboembolism, as thromboprophylaxis with low-dose direct oral anticoagulants has been shown to reduce major and fatal vascular events, especially against a background of dual pathway inhibition with aspirin. In addition, recent post hoc analyses from randomized trial data have established 5 key bleeding-risk factors that, if removed, reveal a low-bleeding- risk medically ill population and, conversely, key individual risk factors, such as advanced age, a past history of cancer or VTE, an elevated D-dimer, or the use of a validated VTE risk score—the IMPROVE VTE score using established cutoffs—to predict a high-VTE-risk medically ill population that benefits from extended postdischarge thromboprophylaxis. Last, thromboprophylaxis of a high-thrombotic-risk subset of medically ill patients, those with COVID-19, is rapidly evolving, both during hospitalization and post discharge. This article reviews 3 controversial topics in the thromboprophylaxis of hospitalized acutely ill medical patients: (1) clinical relevance of key efficacy and safety outcomes incorporated into randomized trials but not incorporated into relevant antithrombotic guidelines on the topic, (2) the use of individual risk factors or risk models of low-bleeding-risk and high-thrombotic-risk subgroups of medically ill inpatients that benefit from extended thromboprophylaxis, and (3) thromboprophylaxis of hospitalized COVID-19 patients, including extended postdischarge thromboprophylaxis.

Learning Objectives

Understand the relevant efficacy and safety outcomes in assessing the net clinical benefit of a strategy of thromboprophylaxis in medical inpatients, including a holistic interpretation of VTE and ATE

Define the low-bleeding-risk and high-VTE-risk subgroups of hospitalized medically ill patients that benefit from extended thromboprophylaxis, utilizing either individual clinical risk factors, an elevated biomarker (D-dimer), or the validated IMPROVE VTE risk score using established cutoffs

Utilize evidence-based thromboprophylactic strategies in hospitalized COVID-19 patients, including those in critical care settings and in the immediate postdischarge period

Introduction

The field of thromboprophylaxis for hospitalized acutely ill medical patients, including those hospitalized for COVID-19, is rapidly evolving, both in the inpatient setting and the immediate posthospitalization discharge period. It is estimated that annually over 7.2 million hospitalized acutely ill medical patients are at risk for venous thromboembolism (VTE) in the US alone.1 However, modeling studies reveal that approximately 50% of low-risk patients may receive too much prophylaxis in inpatient settings and subjected to the unnecessary harms of pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis. In contrast, 25% or more of high-risk patients do not receive adequate thromboprophylaxis, usually because they do not receive an adequate duration of posthospital discharge thromboprophylaxis, with consistent data revealing that 50% to 60% or more thrombotic events occur during this postdischarge period.1-3 This is highlighted by the fact that fewer than 4% of patients in the US receive some type of postdischarge anticoagulant prophylaxis and that the shortening hospital length of stay for these patients in US settings (mean, 4-5 days) is dampening the treatment effect of inpatient thromboprophylaxis.1,4 In addition, there continues to be incongruity between data leading to the US Food and Drug Administration's approval of 2 direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) for the extended thromboprophylaxis of medically ill patients based on clinically appropriate end points and definitions of low-bleeding-risk and high-VTE-risk populations and the incorporation of these end points and defined groups into antithrombotic guidelines, notably the American Society of Hematology (ASH) 2018 Guidelines for Management of Venous Thromboembolism in hospitalized medical patients.5 Last, the last 2 years have established a particularly high thrombotic risk population of medically ill patients with pneumonia/sepsis—namely, patients hospitalized for COVID-19—that warrants separate discussions on thromboprophylaxis.6

This article reviews 3 controversial topics in the thromboprophylaxis of hospitalized acutely ill medical patients: (1) the clinical relevance of key efficacy and safety outcomes incorporated into randomized trials but not incorporated into relevant antithrombotic guidelines on the topic, (2) the use of individual risk factors or risk models of low-bleeding-risk and high- thrombotic-risk subgroups of medically ill inpatients that benefit from extended thromboprophylaxis, and (3) the thromboprophylaxis of hospitalized COVID-19 patients, including extended postdischarge thromboprophylaxis.

CLINICAL CASE 1

A 78-year-old woman with a history of left-breast cancer who underwent mastectomy 4 years ago and has a history of congestive heart failure (last echocardiogram with ejection fraction, 38%) presented with severe pneumonia. Her plasma brain-type natriuretic peptide was 500 pg/mL, her renal function revealed an estimated glomerular filtration rate of 55 mL/min, and her D-dimer (DD) was 1200 fibrinogen equivalent units (upper limit, 500). She required pressor support, with a 2-day stay in the intensive care unit (ICU) and intravenous antibiotics and in-hospital thromboprophylaxis of 5000 IU of unfractionated heparin (UFH) twice daily. After a 5-day hospital stay, she was ready to be discharged. Would you give postdischarge thromboprophylaxis?

Relevant efficacy and safety outcomes in clinical trials and antithrombotic guidelines for medically ill patients

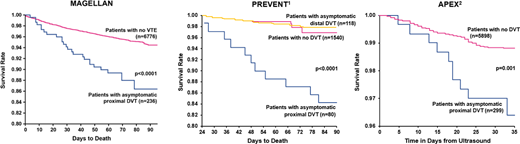

Since 1986 both antithrombotic clinical trials and guidelines have included asymptomatic proximal deep vein thrombosis (DVT) found by screening ultrasonography as a relevant outcome in assessing the net clinical benefit of an antithrombotic strategy in hospitalized patients, as previous data in surgical patients clearly showed that asymptomatic events in particular had the potential to be lethal. For the introductory statement of the 2012 eighth edition Chest guidelines, “reevaluation” of the need to measure “patient-centered” outcomes in “naturalistic settings” by Drs John Eikelbom and Jack Hirsh excluded the use of asymptomatic DVT found by venography or ultrasonography as a relevant patient-centered outcome and confined it to a “surrogate outcome” with no value in assessing the potential benefits of a thromboprophylactic strategy from a clinical guideline perspective.7 The authors provided no evidence to corroborate these statements. This principle of assessing asymptomatic proximal DVT as an outcome with no importance from a patient-centric perspective was extended to the 2018 ASH guidelines on the prevention of VTE in hospitalized medical patients.5 However, 2 previous subgroup analyses from randomized trials revealed a significant association between asymptomatic proximal (but not distal) DVT found by screening ultrasonography and mortality in hospitalized medical patients (Figure 1), and a more recent publication from a subgroup analysis of the MAGELLAN trial also found a significant association between asymptomatic proximal DVT and mortality in hospitalized medical patients (hazard ratio [HR], 2.31; 95% CI, 1.52-3.51; P < .0001), in addition to symptomatic disease (Figure 1).8-10 These consistent results clearly identify asymptomatic proximal DVT as an important patient-centered outcome in trials of venous thromboprophylaxis that is associated with death (as is symptomatic VTE), necessitating a reevaluation of both future clinical trial designs as well as antithrombotic guidelines in medically ill patients. Although one can argue that asymptomatic proximal DVT is a marker of disease severity or comorbidity in a medically ill patient, there is no evidence as to why these events (and not symptomatic VTE) are uniquely qualified to represent disease severity. Indeed, asymptomatic proximal DVT is not a surrogate but a relevant outcome and may represent a worse form of VTE than symptomatic disease due to its clinically silent nature. Thus, asymptomatic DVT found by screening venography or ultrasonography represented a key end point when executing previous clinical trials of thromboprophylaxis for VTE.

When evaluating safety end points, clinical trials have included major and clinically relevant nonmajor bleeding as part of the principal safety outcomes assessing overall net clinical benefit from a thromboprophylactic strategy in hospitalized medically ill patients.11 Recent evidence from trials of the extended thromboprophylaxis of medical inpatients suggests that major bleeding (HR, 8.53; 95% CI, 5.61-12.97; P < .0001 and HR, 3.46; 95% CI, 1.24-9.61; P = .017), but not clinically relevant nonmajor bleeding, is consistently and strongly associated with mortality (Figure 2).12 As such, major bleeding—but not clinically relevant nonmajor bleeding—would be an appropriate principal safety end point in clinical antithrombotic trials or antithrombotic guidelines in hospitalized medical patients when evaluating net clinical benefit.

Association between major bleeding, nonmajor clinically relevant bleeding (NMCR), trivial bleeding, and no bleeding and mortality in the MAGELLAN trial (

above) and MARINER trial (below). Reproduced with permission from Spyropoulos et al.12

Association between major bleeding, nonmajor clinically relevant bleeding (NMCR), trivial bleeding, and no bleeding and mortality in the MAGELLAN trial (

above) and MARINER trial (below). Reproduced with permission from Spyropoulos et al.12

The latest evidence from randomized trials of extended postdischarge thromboprophylaxis reveals that a low-dose DOAC has the potential to reduce not only total (including asymptomatic) VTE during this period but arterial thromboembolism (ATE) as well. The concept of the interrelatedness of VTE and ATE, both sharing common risk factors and a common pathophysiology, has been established for some time,13 but the potential to enhance the efficacy of an antithrombotic strategy in medical inpatients using a dual pathway inhibition strategy of low-dose extended anticoagulants against background antiplatelet therapy with a final common pathway to reduce thrombin potential and platelet activation has only recently been developed (Figure 3).14 Post hoc data from the APEX trial revealed a significant reduction of all-cause stroke (ischemic, hemorrhagic, uncertain) and ischemic stroke with betrixaban (relative risk [RR], 0.56; 95% CI, 0.32-0.96; P = .032 and RR, 0.53; 95% CI, 0.30-0.94; P = .026) as well as fatal and irreversible vascular events (HR, 0.73; 95% CI, 0.55-0.98; P = .0330).15,16 This concept was prospectively evaluated with a prespecified analysis of the MARINER trial, showing that low-dose rivaroxaban significantly reduced major and fatal vascular events, including symptomatic VTE, myocardial infarction, stroke, and cardiovascular death (HR, 0.72; 95% CI, 0.52-1.00; P = .049).17 Incorporating major and fatal thromboembolic outcomes (including VTE and ATE) in a strategy of extended thromboprophylaxis of medically ill patients has the potential to reduce these outcomes by 22% (HR, 0.78; 95% CI, 0.63-0.97; P = .024), with a number needed to treat to prevent 1 event of 197 (absolute risk difference, 0.51%), thus preventing 10 major or fatal thromboembolic events for every severe bleeding event caused.10 These results have implications in the design of future randomized trials and antithrombotic guideline assumptions in pairing relevant efficacy as well as safety end points.

Mechanisms of dual pathway inhibition with low-dose DOACs and antiplatelet therapy mediating thrombin-derived mechanisms of both VTE and ATE in medically ill patients.

ADP, adenosine diphosphate; COX, cyclooxygenase; FIX, factor XI inhibitors; GP, glycoprotein; P2Y1, platelet ADP P2Y1 receptor; TXA2, thromboxane A2; VWF, von Willebrand factor. Reproduced with permission from Goldin et al.14

Mechanisms of dual pathway inhibition with low-dose DOACs and antiplatelet therapy mediating thrombin-derived mechanisms of both VTE and ATE in medically ill patients.

ADP, adenosine diphosphate; COX, cyclooxygenase; FIX, factor XI inhibitors; GP, glycoprotein; P2Y1, platelet ADP P2Y1 receptor; TXA2, thromboxane A2; VWF, von Willebrand factor. Reproduced with permission from Goldin et al.14

Extended post–hospital discharge thromboprophylaxis of hospitalized medical patients and defining low-bleeding-risk and high-VTE-risk populations that benefit from such a strategy

The results of extended thromboprophylaxis trials with the low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) enoxaparin or the DOACs apixaban, rivaroxaban, and betrixaban compared to standard in-hospital thromboprophylaxis with LMWH followed by placebo (or simply DOAC vs placebo post discharge) had mixed results, either from not achieving their primary end point or because of an increase in major bleeding (including critical site and fatal bleeding).1 A meta-analysis of these trials revealed an overall 39% reduction of symptomatic VTE and VTE-related death (RR, 0.61; 95% CI, 0.44-0.83; P = .002) that was offset by a 2-fold increase in major and fatal bleeding RR, 2.04; 95% CI, 1.42-2.91; P < .001).18 The 2018 ASH guidelines for the management of VTE issued a strong recommendation for inpatient over inpatient plus extended-duration outpatient VTE prophylaxis based on moderate certainty in the evidence of effects.5 The authors based this recommendation only on symptomatic VTE events and included therapies that were not approved while discussing the need to define high-VTE-risk and low-bleeding-risk populations that may benefit from a strategy of extended thromboprophylaxis.

Since the publication of the 2018 ASH guidelines, multiple analyses from randomized trial data have helped to define subgroups of hospitalized medical patients that benefit from extended thromboprophylaxis. A key post hoc analysis of the MAGELLAN trial—which met its primary efficacy end point but revealed a nearly 3-fold increased risk of major (including fatal) bleeding—defined 5 key exclusionary high-bleeding-risk factors that predicted a low-bleeding-risk population in the MARINER trial: active cancer, dual antiplatelet therapy at baseline, bronchiectasis/pulmonary cavitation, gastroduodenal ulcer, or bleeding within 3 months before randomization (Table 1).19 The incorporation of these 5 key bleeding-risk factors excluded 20% of the MAGELLAN population, and in the remaining 80%, net clinical benefit analyses revealed that the efficacy of rivaroxaban was maintained (and potentially enhanced) but that the safety was greatly enhanced, with the risk of major bleeding halved and no longer significant (0.7% vs 0.5%; RR, 1.48; 95% CI, 0.77-2.84). Importantly, the risk of fatal bleeding was reduced to less than 0.1%.19

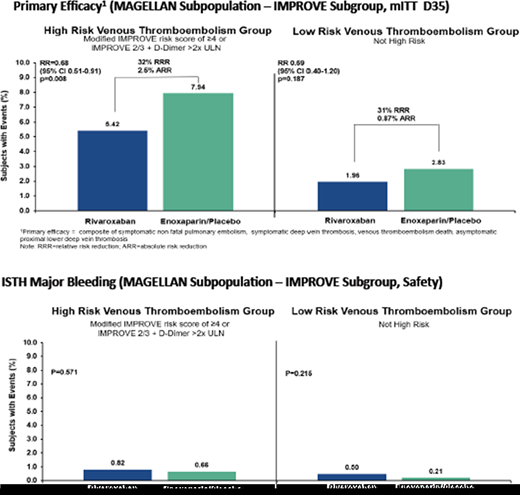

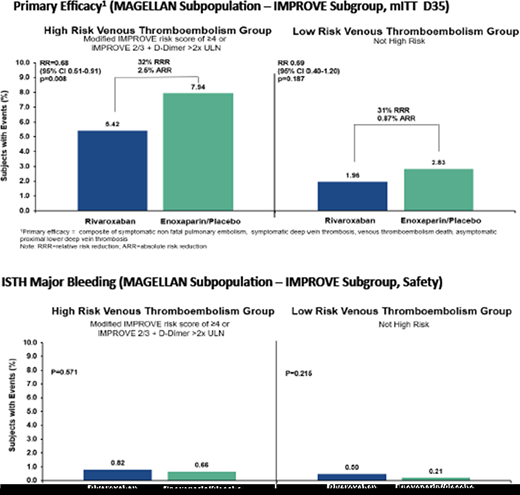

In terms of defining high postdischarge VTE risk, a group of VTE risk factors collectively called the APEX (age, past history, extra risk factors) criteria, including an age over 75 years, a past history of cancer or VTE, and extra risk factors (comorbidities that are risk factors for VTE), has been shown to identify a high-VTE-risk population that benefited from extended thromboprophylaxis, as shown in the APEX trial (Table 2).20,21 An analysis from the MAGELLAN trial defined an elevated DD (>2 times the upper limit of normal [ULN]) as an important new biomarker in defining high-VTE-risk subgroups of medically ill patients that benefit from extended thromboprophylaxis (Table 2).22 Last, an important post hoc analysis of the MAGELLAN trial incorporated a widely validated VTE risk score in medically ill patients—the modified IMPROVE VTE risk score—using a cutoff score greater than or equal to 4 or a score of 2 and 3 and elevated DD (>2 times ULN) (Table 2) to identify a nearly 3-fold higher VTE risk subpopulation of patients. Coupled with the low-bleeding-risk criteria already discussed, it was finally able to identify a hospitalized, medically ill population in which a significant benefit existed for extended thromboprophylaxis, leading to an overall net clinical benefit of such a strategy (total VTE in the high-risk enoxaparin/placebo group [7.94%] vs total VTE in the high-risk rivaroxaban group [2.83%] [RR, 0.68; 95% CI, 0.51-0.91; P = .008], a result not seen in the lower-VTE-risk group [RR, 0.69; 95% CI, 0.40-1.20; P = .187]) (Figure 4).23

Net clinical benefit of postdischarge extended thromboprophylaxis in hospitalized medical patients in the MAGELLAN trial from identifying a low-bleeding-risk group (excluding 5 key bleeding-risk factors) and a high-VTE-risk group (utilizing an IMPROVE VTE score of ≥4 or a score of 2 or 3 and elevated DD >2 times ULN).

ARR, absolute risk reduction; ISTH, International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis; RRR, relative risk reduction. Reproduced with permission from Spyropoulos et al.23

Net clinical benefit of postdischarge extended thromboprophylaxis in hospitalized medical patients in the MAGELLAN trial from identifying a low-bleeding-risk group (excluding 5 key bleeding-risk factors) and a high-VTE-risk group (utilizing an IMPROVE VTE score of ≥4 or a score of 2 or 3 and elevated DD >2 times ULN).

ARR, absolute risk reduction; ISTH, International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis; RRR, relative risk reduction. Reproduced with permission from Spyropoulos et al.23

These low-bleeding-risk and high-VTE-risk subgroups led to US Food and Drug Administration approval in 2017 and 2019 of the DOACs betrixaban (which is no longer available) and rivaroxaban for extended thromboprophylaxis.24,25 Formal benefit/risk analysis of the approved 10-mg dose of rivaroxaban using the medically ill populations studied above at low bleeding risk but high VTE risk reveals that per 10 000 patients treated, rivaroxaban at the 10-mg dose resulted in 32.5 (95% CI, −68.1, 3.0) fewer symptomatic VTE events and VTE-related deaths at the expense of 8.2 (95% CI, −12.2, 28.5) additional major bleeding events, with a number needed to treat of 308 to prevent symptomatic VTE and VTE-related death and a number needed to harm of 1224 to incur one major bleed. Furthermore, the observed benefits extended to 63.0 (95% CI, −113.5, −12.5) fewer composite end points of nonfatal pulmonary embolism, myocardial infarction, nonhemorrhagic stroke, and nonhemorrhagic all-cause mortality with no excess in the composite of critical site and fatal bleeding (Figure 5A).26 The positive benefit/risk profile begins early and increases over time during the course of extended thromboprophylaxis (Figure 5B).26 These data have important populational health implications, with conservative estimates of applying extended thromboprophylaxis in appropriately selected patients leading to an estimated reduction of approximately 20 000 fewer symptomatic VTE events and 12 000 fewer VTE-related deaths at the cost of approximately one-fourth of those numbers in major or fatal bleeding events in a European population of medically ill patients.27 There is an ongoing clustered randomized trial (NCT04768036)—IMPROVE—to assess the impact of the IMPROVE-DD VTE score in selected hospitalized medically ill patients using established cutoffs for extended thromboprophylaxis and embedded into the clinical workflow at admission and at discharge using an electronic health-record agnostic platform. The trial is assessing whether outcomes, including VTE and ATE, are improved using this technology. None of these data assessing the benefit/risk of extended thromboprophylaxis in low-bleeding-risk and high-VTE-risk medically ill populations has been incorporated into updated antithrombotic guidelines, including the 2018 ASH guidelines.

(A) Cumulative rate difference of extended thromboprophylaxis with rivaroxaban per 10 000 patients utilizing various efficacy and safety end points. (B) Cumulative rate difference of extended thromboprophylaxis with rivaroxaban per 10 000 patients over time (45 days from randomization). ACM, all-cause mortality; CV, cardiovascular; MI, myocardial infarction; PE, pulmonary embolism. Reproduced with permission from Raskob et al.26

(A) Cumulative rate difference of extended thromboprophylaxis with rivaroxaban per 10 000 patients utilizing various efficacy and safety end points. (B) Cumulative rate difference of extended thromboprophylaxis with rivaroxaban per 10 000 patients over time (45 days from randomization). ACM, all-cause mortality; CV, cardiovascular; MI, myocardial infarction; PE, pulmonary embolism. Reproduced with permission from Raskob et al.26

Thromboprophylaxis of hospitalized COVID-19 patients

Patients hospitalized for COVID-19 are a particularly high- thrombotic-risk subgroup of medically ill patients with a 3- to 5-fold increased risk of VTE in hospital wards and especially in critically ill settings, compared to historical matched controls, due to a “perfect storm” involving the immune system, coagulation system, and inflammatory system, as well as endothelial dysfunction, in addition to classic patient-related VTE risk factors.6,28 Due to these observations, multiple cardiovascular and antithrombotic societies have advocated for universal thromboprophylaxis of hospitalized COVID-19 patients using standard prophylactic-dose (low-dose) LMWH or UFH.29,30 Approximately 20 global randomized trials have assessed whether the use of escalated or therapeutic-dose heparins (mostly LMWH) confer additional advantages over standard-dose heparins both in noncritically ill and critically ill patients.31 Entry criteria were either broad or used enriched populations.31 Study end points included either all-cause mortality, or a composite of mortality and thrombotic diseases, or mortality and need for end-organ support.31 There were 2 basic clinical trial designs: (1) the use of LMWH/UFH as an add-on treatment approach in reducing the severity/morbidity of COVID-19 pneumonia or (2) the use of heparins as classic antithrombotic agents in reducing macrovessel thromboembolic complications and mortality, presumably from thrombosis.

The results of these trials were mixed, as shown in Table 3. None of the trials showed advantages to the use of escalated- or treatment-dose heparins in critically ill populations, but conversely, they did show excess harm from an increased risk of major bleeding. For noncritically ill populations, 2 of the trials that met their primary end point revealed that therapeutic heparin (mostly LMWH) reduced the need for organ support and improved survival until hospital discharge or reduced a composite of major thromboembolism and all-cause mortality without a significant increase in major bleeding (Table 3).32,33 A third trial that did not meet its primary end point also revealed in a secondary outcome a reduction in mortality with therapeutic LMWH.34 These trials either had entry criteria using elevated DD (>2 times or >4 times the ULN) or increased oxygen requirements or had greater absolute treatment effects in populations with elevated DD. Last, a more recent trial that selected a high-risk hospitalized COVID-19 population using the IMPROVE-VTE score of greater than or equal to 4 or 2 to 3 with a DD of more than 500 ng/mL and randomized patients at hospital discharge to rivaroxaban 10 mg daily or no anticoagulation for 35 days found an approximately 6% absolute risk reduction or 67% relative risk reduction (RRR) of major thromboembolism and cardiovascular death favoring rivaroxaban (RR, 0.33; 95% CI, 0.13-0.90; P = .03) for superiority.35

Antithrombotic guidelines for hospitalized COVID-19 patients have now been updated to suggest or recommend standard-dose heparins for thromboprophylaxis in medical ward and critically ill patients and the use of therapeutic-dose heparin (LMWH) in select noncritically ill patients, especially those with elevated DD (>2 times ULN) or increased oxygen requirements.30,36-39 The National Institutes of Health and the most recent 2022 International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis guidelines also suggest the use of extended thromboprophylaxis (10 mg of rivaroxaban daily) in patients at low bleeding risk and high VTE risk (based on IMPROVE VTE score criteria).36,39 Curiously, the 2022 ASH guidelines on the topic do not advocate for extended thromboprophylaxis despite recent data from randomized trials.30

CLINICAL CASE (Continued)

The patient is an older adult (age >60 years), has a recent history of breast cancer, was relatively immobilized in a hospital setting, briefly required an ICU level of care, and has elevated DD levels higher than 2 times that of the ULN. She has no obvious bleeding risk factors. She has an IMPROVE VTE score of 5, an IMPROVE-DD VTE score of 7, and meets 2 out of 3 APEX criteria (age >75 years and a history of cancer). She will benefit from extended postdischarge thromboprophylaxis with rivaroxaban at 10 mg once daily for 35 days.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure

Alex C. Spyropoulos: consultancy: Alexion, ATLAS Group; Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol Myers Squibb, Janssen, Sanofi; research funding: Janssen, Boehringer Ingelheim.

Off-label drug use

Alex C. Spyropoulos: nothing to disclose.