Abstract

In contrast to B-cell lymphoma, the advent of modern targeting drugs and immunotherapeutics has not led to major breakthroughs in the treatment of peripheral T-cell lymphoma (PTCL) to date. Therefore, both autologous and allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT) continue to play a central role in the management of PTCL. Focusing on the most common entities (PTCL not otherwise specified, angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma, and ALK-negative anaplastic large cell lymphoma), we summarize evidence, indications, and points to consider for transplant strategies in PTCL by treatment line. Although cutaneous T-cell lymphomas (CTCLs) are biologically and clinically distinct from the aforementioned PTCL, both disease groups appear to be susceptible to the graft-versus-lymphoma effects conferred by allogeneic HCT (alloHCT), setting the stage for alloHCT as a potentially curative treatment in otherwise incurable CTCL, such as mycosis fungoides/Sezary syndrome. Nevertheless, specific aspects regarding indication and prerequisites for alloHCT in CTCL need to be considered. Given the inherent toxicity of alloHCT and the significant risk of relapse after transplant, only intelligent strategies embedding alloHCT in current PTCL/CTCL treatment algorithms in terms of patient selection, timing, pretransplant preparation, and posttransplant maintenance provide optimal results. New targeted and cellular therapies, either complementary or competitive to HCT, are eagerly awaited in order to improve PTCL/CTCL outcomes.

Learning Objectives

Explain the rationale, indications, risks, and outcomes of autologous and allogeneic HCT in PTCL

Apply concepts of how to perform HCT in patients with PTCL

Differentiate the indications and specific aspects of alloHCT in patients with MF/SS

Introduction

In contrast to B-cell lymphoma, for which a variety of innovations have significantly broadened the treatment armamentarium and improved prognosis, therapeutic progress in the field of peripheral T-cell lymphoma (PTCL) has been limited during the past decades. Although multiple novel approaches have been under investigation, such as histone deacetylase inhibitors, pathway inhibitors, antibody drug compounds, checkpoint inhibitors, and CAR T cells, only brentuximab vedotin has an accepted place in clinical routine.1 Thus, the backbone of PTCL management remains conventional chemotherapy followed by consolidative high-dose intensification with autologous hematopoietic cell transplantation (autoHCT) in transplant-eligible chemosensitive patients and, in the relapsed/refractory (R/R) setting, allogeneic HCT (alloHCT) for all transplant-eligible patients.2-4

Here we summarize our understanding of the current role of autoHCT and alloHCT in the management of PTCL with a major focus on the common nodal entities—namely PTCL, not otherwise specified (NOS), anaplastic large cell lymphoma (ALCL), and angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma (AITL or nodal T-follicular helper cell lymphoma, angioimmunoblastic type)—which make up about 75% of all PTCL cases.4-7

In a second part, we touch on HCT in mycosis fungoides/Sezary syndrome (MF/SS) as the most common cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL), a biologically and clinically distinct entity with treatment principles that in many ways differ from those of other T-cell lymphomas.

CLINICAL CASE

A 48-year-old man presented with ubiquitous lymphadenopathy and splenomegaly, accompanied by pronounced B symptoms. A workup led to the diagnosis of PTCL-NOS with bone marrow infiltration and a pro-inflammatory status as indicated by elevations of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), C-reactive protein, and sCD25. Ann Arbor stage was IVB with Age-Adjusted International Prognostic Index (aaIPI) high-intermediate. Standard chemotherapy consisting of 6 cycles of cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, etoposide, vincristine, and prednisolone (CHOEP) resulted in rapid symptom control, resolution of serum marker abnormalities, and complete metabolic response.

Frontline setting

Evidence for autoHCT or alloHCT for consolidation of first-line therapy responses

According to current guidelines, our patient was offered consolidation with high-dose therapy and autoHCT. This recommendation is essentially based on 2 large prospective phase 2 trials, showing long-term progression-free survival (PFS) by intent-to-treat (ITT) between 30% and 45%.8,9 These results were confirmed in the recently published prospective AATT (Autologous or Allogeneic Transplantation in T-Cell Lymphoma) trial (Table 1).10,11 Some real-world series and also an exploratory subgroup analysis of the ECHELON2 trial showed significant superiority of first-line autoHCT consolidation over nontransplant strategies,7,12,13 thereby supporting this concept.

However, real-world studies are heavily biased by confounders related to eligibility and access to HCT, and other retrospective analyses did not find an advantage for consolidative first-line autoHCT.14,15 Thus, with the only phase 3 study comparing autoHCT consolidation to observation still ongoing (Bachy et al. NCT05444712), the value of consolidative autoHCT in patients with complete metabolic response after standard first-line chemotherapy remains unsettled. Indeed, early positron emission tomography (PET) negativity—eg, after 2 courses of CHOP (iPET2 negative)—may herald excellent survival even without consolidative auto-HCT.16 Notably, all studies mentioned here excluded ALK-positive ALCL because of its generally favorable outcome with standard chemotherapy, implying that no evidence supports consolidative autoHCT in ALK-positive ALCL.17

Regarding up-front alloHCT, the AATT study compared autoHCT with myeloablative alloHCT as first-line consolidation by intent to treat and did not find significant differences in terms of PFS and overall survival (OS).10 Although the alloHCT-related graft-versus-lymphoma (GVL) effect resulted in a remarkably low relapse rate of 8%, the high nonrelapse mortality (NRM) associated with alloHCT in this study (31%) counterbalanced the GVL benefit, and therefore AATT failed to show an advantage of consolidative alloHCT over autoHCT. It remains an open question whether alternative allotransplantation strategies, including less aggressive conditioning, modern graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) prophylaxis, and earlier, interim PET-guided alloHCT, could improve PTCL outcomes in the frontline setting.

CLINICAL CASE (continued)

Four weeks after the last CHOEP14 cycle, the patient underwent high-dose BEAM (carmustine, etoposide, cytosine-arabinoside, and melphalan)/autoHCT. After an uneventful peritransplant course, the patient presented 3 weeks after discharge with fever of unknown origin along with increased LDH and C-reactive protein. Imaging showed enlarged mediastinal and para-aortic lymph nodes and spleen. After biopsy guided by computed tomography confirmed relapse, a donor search was launched and salvage dexamethasone, high-dose cytarabine, and cisplatin initiated, again resulting in rapid clinical improvement and the complete regression of morphological and serological disease. Without delay, the patient proceeded to alloHCT from a matched unrelated donor after conditioning with fractionated total body irradiation (TBI) of 8 Gy, fludarabine, and anti–T-lymphocyte globulin. The early posttransplant course was complicated by steroid- sensitive enteric acute GVHD and reactivation of Epstein-Barr virus, readily controlled by standard measures. One year after alloHCT, the patient is a full chimera and lives relapse-free and off immunosuppression with mild signs of chronic GVHD.

Salvage setting: sensitive relapsed/primary refractory disease

Evidence for autologous or allogeneic transplantation: transplant registry studies

The outlook for patients with PTCL failing first-line therapy is poor if salvage HCT cannot be performed, with a median OS between 3 and 12 months and only a few patients surviving long-term.6,11,15 Thus, current guidelines recommend alloHCT or autoHCT for consolidation of transplant-naive patients responding to salvage chemo(immuno)therapy.2,3,17 Since autoHCT basically represents intensified chemotherapy, there is some rationale—after primary chemotherapy has failed—for switching to an alternative treatment principle in the form of the cellular immunotherapy provided by alloHCT. Evidence for GVL efficacy in PTCL is circumstantial but includes the plateaus observed after reduced-intensity alloHCT in patients with refractory disease or having failed autoHCT, as well as successful posttransplant immunomodulation (ie, immunosuppression tapering, donor lymphocyte infusions).18,19

Nonetheless, registry data and meta-analyses comparing autoHCT and alloHCT in patients with chemosensitive R/R PTCL generally do not show a clear-cut superiority of allotransplantation.20,21 Although disease control is usually superior after alloHCT, this is counterbalanced by the higher NRM associated with allotransplants. Interpreting such data must take into account that transplant registries have a fundamental limitation: considering only patients who actually made it to transplant causes massive selection bias, and this bias may be substantially different between patients selected for autoHCT and alloHCT, respectively. Furthermore, the proportion of transplant candidates who for any reason never proceeded to HCT remains unknown in registry studies, precluding valid judgment of the real impact of autoHCT and alloHCT on the course of the underlying disease.22

Evidence for autologous or allogeneic transplantation: intent-to-transplant studies

Only studies reporting outcomes from the time of relapse avoid the aforementioned bias. Select studies on PTCL following this design are summarized in Table 2. Although survival does not seem to differ meaningfully between studies including higher or lower proportions of patients transplanted,6,11,15,23 patients without transplant are rarely found among long-term survivors, and with 5-year OS rates of 50% to 65% measured from the time of first-line treatment failure the best survival by far is observed with allogeneic transplantation. This argues in favor of performing alloHCT in R/R PTCL whenever possible, even though selection bias again cannot be ruled out and unfit or older patients may not be eligible for alloHCT.

Salvage setting: refractory disease

As the efficacy of autoHCT in patients with chemorefractory PTCL is poor,21 it is not recommended by current guidelines.3,17 In contrast, alloHCT seems to be capable of providing long-term survival in about one-third of patients with PTCL entering the procedure with resistant disease.11,24-27 HCT indications in the main PTCL entities are summarized in Box 1.

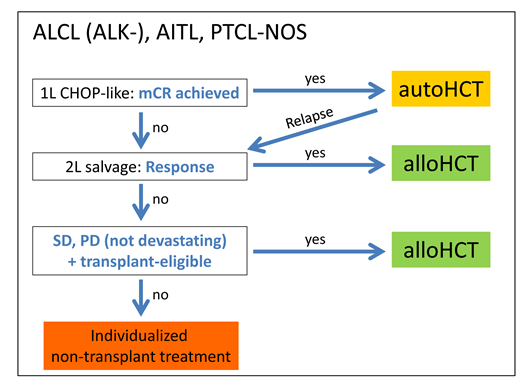

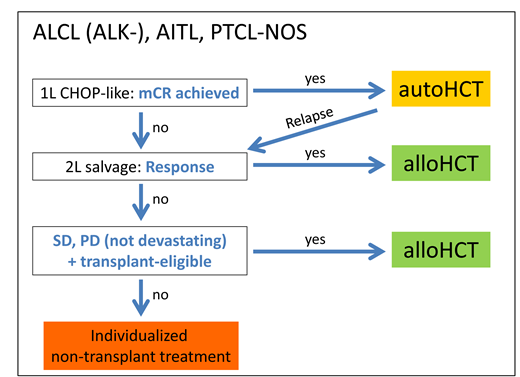

How we treat: HCT in the main PTCL entities (ALCL, AITL, PTCL-NOS)

Frontline setting: We offer consolidative autoHCT to all eligible complete responders to standard frontline therapy. Patients with ALK-positive ALCL or iPET2 negativity (negative PET after 2 courses of chemotherapy) may not need autoHCT.17 All other outcomes are considered failures and treated accordingly.

Salvage setting, sensitive disease: We immediately start a donor search for all transplant-eligible patients with first-line treatment failure but discuss autoHCT in transplant-naive patients relapsing from CR1 who achieve another metabolic complete response upon salvage therapy. All other eligible patients would be advised to proceed to alloHCT.

Salvage setting, refractory disease: If a clinical trial with a really promising novel agent is not available, proceed to alloHCT right away in salvage-refractory patients, avoiding further and mostly futile attempts to induce a remission as long as transplant eligibility is retained.

How to perform HCT in PTCL

Transplant eligibility and risk factors

Due to numerous improvements including donor selection, conditioning, GVHD prophylaxis, and supportive care, the mortality and morbidity associated with autologous and in particular allogeneic HCT have considerably decreased over the past decades, allowing transplants to be offered to older and comorbid patients in PTCL (Table 3).21,24,28,29Table 4 indicates that despite this, higher age and poor performance status (PS) continue to have an impact on the prognosis of patients undergoing alloHCT for R/R PTCL. Among the disease-related factors, remission status at HCT but, notably, not treatment line (salvage vs up-front) affects alloHCT outcome.11,25 Accordingly, transplant eligibility has to be weighed on an individual basis, taking into account age, comorbidity, PS, frailty, and donor compatibility, along with disease status.

Bridging to transplant

Bridging to transplantation in R/R PTCL means salvage chemotherapy to reduce the tumor burden and stabilize the patient's condition in order to facilitate transplant success. If a clinical trial is not available, current guidelines should be followed.17 Usually, we use platinum-based combination chemotherapies for the first salvage attempt.15

Preparative regimen and conditioning

In 1 of the pivotal trials establishing consolidative autoHCT as the standard of care in PTCL frontline treatment, BEAM was used for high-dose therapy,8 while TBI with cyclophosphamide was employed in the other major trial.9 Although there were no obvious outcome differences across these 2 trials and comparative analyses are lacking, BEAM has been widely adopted and represents today's standard of care for high-dose therapy in PTCL autotransplants.3,14

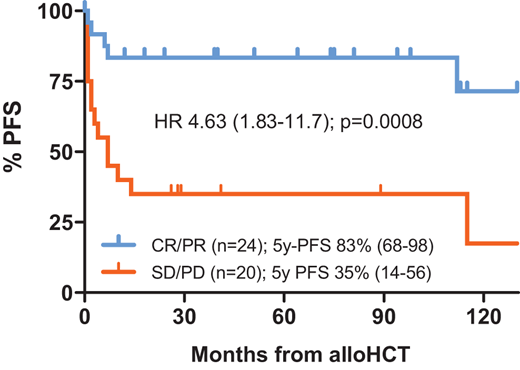

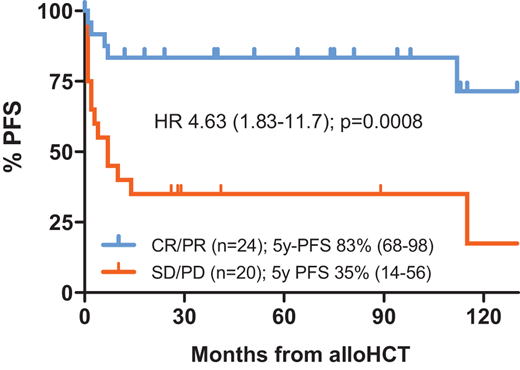

As the basis of alloHCT in R/R PTCL is GVL-mediated immunotherapy, the contribution of conditioning cytotoxicity to disease control may be less critical. Accordingly, myeloablative conditioning did not emerge as a significant PFS predictor in recent larger registry studies on PTCL allotransplants (Table 4); if anything, it tends to be associated with adverse outcomes.18,30,31 Similar to the autologous setting, the role of TBI as part of the conditioning regimen is unsettled, even though in our hands a regimen of intermediate-dose TBI and fludarabine yielded favorable results with 5-year PFS rates of 83% and 35% in sensitive and refractory PTCL, respectively (Figure 1).27 Overall, current evidence supports the use of reduced-intensity conditioning in PTCL,3 thereby extending the allotransplant option also to older and comorbid patients.

PFS after alloHCT for R/R PTCL using conditioning with fractionated TBI (4 × 2 Gy) and fludarabine by disease status at HCT. Single-center data from the University of Heidelberg; 44 consecutive patients transplanted 2010-2023; median follow-up 6.4 (range, 1.0-13.3) years. Blue curve, patients with sensitive disease; red curve, patients with refractory disease. CR, complete response; HR, hazard ratio; PD, progressive disease; PR, partial response; SD, stable disease.

PFS after alloHCT for R/R PTCL using conditioning with fractionated TBI (4 × 2 Gy) and fludarabine by disease status at HCT. Single-center data from the University of Heidelberg; 44 consecutive patients transplanted 2010-2023; median follow-up 6.4 (range, 1.0-13.3) years. Blue curve, patients with sensitive disease; red curve, patients with refractory disease. CR, complete response; HR, hazard ratio; PD, progressive disease; PR, partial response; SD, stable disease.

Donor selection

Post-HCT relapse prevention strategies

Unlike in B-cell lymphoma and Hodgkin's lymphoma, where antibody-based maintenance and/or minimal residual disease–guided preemptive immunomodulation play a role in distinct entities, there are no established posttransplant strategies for relapse prevention in PTCL.

HCT in rare PTCL entities

Although the indications and points to consider developed from HCT experience with the 3 major T-cell lymphoma entities also partly apply to the rarer PTCL, the latter are characterized by a more diverse biology, clinical course, and management, with important implications for the role and timing of transplant. Some of these (eg, hepatosplenic T-cell lymphoma [HSTL] and high-risk subtypes of adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma [ATLL]) follow a very aggressive course with early chemorefractoriness but can benefit from first-line alloHCT.3,4,17,32,33 On the other side, early-stage extranodal natural killer (NK)/T-cell lymphoma has a good prognosis without the need for first-line HCT consolidation. However, data defining the role of HCT in most rare PTCL indications are scanty, and several recommendations rely on expert opinion rather than evidence (Table 5).3

Transplantation in CTCL

Evidence

Early reports on high-dose therapy and autoHCT for R/R MF/SS gave disappointing results. Relapse rates were high, with very few patients reported to survive long-term (reviewed in Virmani et al34). Accordingly, autoHCT has largely been abandoned in CTCL.3,35

Stable plateaus in the relapse incidence curves and donor lymphocyte infusion efficacy in patients failing alloHCT support the existence of a potentially curative GVL effect in CTCL.35-38 A recent systematic review and meta-analysis including 15 studies suggests that with long-term OS and PFS rates of about 50% and 33%, respectively, the results of alloHCT seem to be superior to any other treatment available for advanced CTCL.37 While NRM after alloHCT for CTCL is in the range reported for other T-cell lymphomas, the major problem is the high relapse rate (around 50%).37

The prospective CUTALLO trial allocated patients aged 70 years or younger with advanced but still responsive MF or SS to alloHCT or no alloHCT depending on the availability of a sibling or matched unrelated donor.38 Melphalan/fludarabine- based reduced-intensity conditioning was administered in the alloHCT arm. Treatment in the nontransplant arm was heterogenous but followed international guidelines. Fifty-five patients were intended to receive alloHCT and 44 patients nontransplant therapy. After a median follow-up of 13 months, 1-year PFS, relapse incidence, and NRM were 50.5%, 45.4%, and 8.5% vs 14.3%, 86%, and 0% in the matched HCT and non-HCT groups, respectively. The 50% 1-year PFS in the transplant arm is in line with that observed for chemosensitive patients in retrospective studies.36 Despite limitations, such as the rather low number of patients actually transplanted and the complex statistical design, this prospective study for the first time presented an ITT comparison of alloHCT with nontransplant strategies in CTCL and strongly supports the role of alloHCT as a real game-changer in transplant-eligible patients with chemosensitive advanced MF/SS (Box 2).

How we treat: HCT in MF/SS

Unlike PTCL, mycosis fungoides cannot be cured with systemic therapy, but in the majority of patients the disease follows an indolent course, in many instances without a significant reduction of life expectancy. Thus, alloHCT should be considered only in eligible patients in stage IIB-III who have failed at least 1 line of systemic therapy and those in stage IV.35 We initiate a donor search as soon as these prerequisites are met but proceed to alloHCT only if at least disease stabilization can be achieved by salvage therapy. There is no role for autoHCT in CTCL.

How to perform alloHCT in CTCL

Basically, considerations regarding transplant eligibility, conditioning, and donor selection follow the same principles as discussed for nodal PTCL, with the important exception that patients with CTCL who proceed to alloHCT in a chemorefractory state do not seem to have a reasonable chance of surviving long-term.36,37 There is some concern about increased GVHD risks after prior exposure to the CCR4 blocker mogamulizumab; this may be addressed by instituting a washout period prior to conditioning.33,39 Preliminary data indicate that the incorporation of TBI or total skin electron beam irradiation into conditioning may improve outcome.36,37,40 Although some small studies suggest better outcomes for SS than for MF after alloHCT, this finding needs further substantiation.37,40

Conclusions

Whereas autoHCT has its place in the consolidation of the first or second complete responses of PTCL, alloHCT undoubtedly is the most effective therapy in both R/R PTCL and advanced CTCL. While adaptive conditioning, along with many other achievements of modern allotransplantation platforms, has significantly attenuated transplant-related morbidity and mortality and made alloHCT accessible for older and comorbid patients in PTCL/CTCL, posttransplant relapse remains the major challenge. Strategies to reduce relapse risk could focus on more effective pretransplant debulking, including innovative drugs that might also be considered for posttransplant maintenance, as well as earlier application of alloHCT before the disease becomes too resistant and the condition of the patient too poor. Generally, the low proportion of transplanted patients in larger real-world studies suggests that HCT is heavily underused in patients with R/R PTCL.6,41 Risk-adapted approaches considering adverse genetic signatures and molecular and metabolic response markers may lead to a reevaluation of first-line alloHCT in PTCL.

Finally, as in the B-cell lymphomas, alloHCT in T-cell lymphoma may be amended or partially replaced by more targeted immunotherapeutic approaches, such as CAR T cells, although the clinical development of such products is still in its infancy.42-44

Conflict-of-interest disclosure

Peter Dreger: consultancy: AbbVie, AstraZeneca, Beigene, Bristol Myers Squibb, Gilead, Miltenyi; speakers bureau: AbbVie, AstraZeneca, BeiGene, Bristol Myers Squibb, Gilead, Riemser, Roche; research funding: Riemser; travel support: Beigene, Gilead; data safety monitoring board: Novartis; chairman: German Working Group for Haematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation and Cellular Therapy.

Norbert Schmitz: research funding: AstraZeneca, Janssen, Roche; travel support: Beigene; stockholder: Bristol Myers Squibb; chair: T-cell subcommittee of the Lymphoma Working Party of the European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation.

Off-label drug use

Peter Dreger: nothing to disclose.

Norbert Schmitz: nothing to disclose.