Abstract

POEMS syndrome is defined by the presence of a peripheral neuropathy (P), a monoclonal plasma cell disorder (M), and other paraneoplastic features, the most common of which include organomegaly (O), endocrinopathy (E), skin changes (S), papilledema, edema, effusions, ascites, and thrombocytosis. Virtually all patients will have either sclerotic bone lesion(s) or co-existent Castleman’s disease. Not all features of the disease are required to make the diagnosis, and early recognition is important to reduce morbidity. Other names for the syndrome include osteosclerotic myeloma, Crow-Fukase syndrome, or Takatsuki syndrome. Because the peripheral neuropathy is frequently the overriding symptom and because the characteristics of the neuropathy are similar to that chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy (CIDP), patients are frequently misdiagnosed with CIDP or monoclonal gammopathy of underdetermined significance (MGUS)-associated peripheral neuropathy. Not until additional features of the POEMS syndrome are recognized is the correct diagnosis made and effective therapies initiated. Clues to an early diagnosis include thrombocytosis and sclerotic bone lesions on plain skeletal radiographs. Therapies that may be effective in patients with CIDP and MGUS-associated peripheral neuropathy (intravenous gammaglobulin and plasmapheresis) are not effective in patients with POEMS. Instead, the mainstays of therapy for patients with POEMS include irradiation, corticosteroids, and alkylator-based therapy, including high-dose chemotherapy with peripheral blood stem cell transplantation.

Overview

The major clinical feature in POEMS syndrome is a chronic progressive polyneuropathy with a predominant motor disability. The acronym POEMS (polyneuropathy, organomegaly, endocrinopathy, M protein, and skin changes) refers to several dominant features of the syndrome; however, there are associated features not included in the acronym including sclerotic bone lesions, Castleman disease, papilledema, thrombocytosis, peripheral edema, ascites, effusions, polycythemia, fatigue and clubbing.1–3 Not all features are required to make the diagnosis; at a minimum, a patient should have the following: the peripheral neuropathy; osteosclerotic myeloma (i.e., a clonal plasma cell dyscrasia and at least one sclerotic bone lesion) or Castleman disease; and at least one of the other features (Table 1 ).3 Though the majority of patients have osteosclerotic myeloma, these same patients usually have only 5% bone marrow plasma cells or less, and rarely have hypercalcemia or renal insufficiency. These characteristics and the superior median survival differentiate POEMS syndrome from multiple myeloma. The plasma cells are virtually always lambda restricted. Though the pathophysiologic mechanism is not well understood, there is a correlation between treating the underlying plasmaproliferative disorder (clone) and clinical improvement. Radiation therapy produces substantial improvement of the neuropathy in more than half of the patients who have a single lesion or multiple lesions in a limited area. If there are widespread lesions, conventional chemotherapy or high-dose chemotherapy and peripheral blood support may be helpful.

Background

Associations between plasma cell dyscrasia and peripheral neuropathy (PN) were well recognized as early as the 1950s by Crow. While only 1%–8% of patients with classic multiple myeloma have neuropathy, a third to a half of patients with osteosclerotic myeloma have neuropathy.3 Moreover, it was found that patients with osteosclerotic myeloma were more likely to have other unusual features, which we now associate with the POEMS syndrome.4,5 Hence, a syndrome distinct from myeloma-associated neuropathy came to be recognized. In 1980 Bardwick coined the acronym POEMS.6

Clinical Manifestations

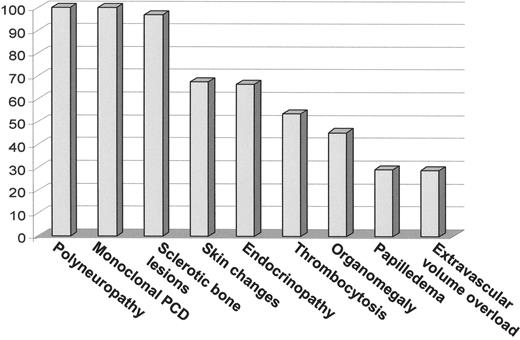

The peak incidence of the POEMS syndrome is in the fifth and sixth decades of life.1,3 Because all series are retrospective and because symptoms can accumulate over time, the prevalence of each of the features varies from series to series as is demonstrated in Table 2. Figure 1 demonstrates the dominant features at the time of diagnosis in the 99 patients with POEMS syndrome seen at the Mayo Clinic from 1975 to 1998. The differential diagnosis of POEMS syndrome includes monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS)-associated neuropathy, chronic inflammatory demyelinating neuropathy (CIDP), primary systemic amyloidosis, and cryoglobulinemia (Table 3 ).

Peripheral neuropathy

All POEMS patients have peripheral neuropathy, which generally dominates the clinical picture. Symptoms begin in the feet and consist of tingling, paresthesias, and coolness. Motor involvement follows the sensory symptoms. Both are distal, symmetric, and progressive with a gradual proximal spread, though rapid progression is also possible. Some patients have significant pain. Sub-clinical to very symptomatic respiratory compromise from neuromuscular weakness also occurs.

Through the neuropathy resembles chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy, POEMS neuropathy has a motor dominance, with marked slowing of conduction velocities with prolonged distal latencies, and progressive dispersion of the compound muscle action potential with stimulation of motor nerves more proximally. On needle electromyography distal fibrillation potentials and enlarged, polyphasic voluntary motor unit action potentials with decreased recruitment are found.7 In general, nerve biopsies demonstrate a combination of axonal degeneration and primary demyelination. Severe endoneurial edema may also be seen, and uncompacted myelin lamellae are observed without immunoglobulin or amyloid deposition.8

Organomegaly

Endocrinopathy

Endocrine abnormalities are defining features of the syndrome, though on autopsy, endocrine glands studied appear architecturally normal and without defining characteristics.1,6,10–12 Diabetes mellitus and gonadal dysfunction are the most common endocrinopathies, though adreno-cortical insufficiency and parathyroid abnormalities have also been described. Given the high prevalence of diabetes and hypothyroidism in the normal population, care should be taken when attributing these disorders to this syndrome such that a patient with MGUS-associated peripheral neuropathy is not incorrectly classified as having POEMS syndrome.

Monoclonal plasmaproliferative disorder

By definition all patients have a monoclonal plasma-proliferative disorder. The monoclonal protein is typically small and will be missed on serum protein electrophoresis in nearly one third of patients if immunofixation is not also done.3 In our series of 99 patients, all patients’ plasma cell clones were lambda restricted. Though clonal plasma cells are detected on biopsy of sclerotic lesions, there may or may not be a clonal plasma cell infiltrate in the bone marrow biopsy of the iliac crest. In general the number of plasma cells is low (median 5%), and the bone marrow is frequently hypercellular and reported out as either “reactive” or as a “myeloproliferative disorder.”

Skin changes

Skin changes occur in 50%–90% of patients, with hyperpigmentation among the most common manifestations. Coarse, longer than normal, black hair often appears on the extremities. Other skin changes include rapid accumulation of hemangiomata, plethora and/or acrocyanosis, skin thickening, white nails and clubbing.1–3

Other features

Osteosclerotic lesions are a defining feature of the syndrome and occur in approximately 95% of patients; one-half have a solitary sclerotic lesion and at least a third have multiple sclerotic lesions. It is common to have mixed osteosclerotic and osteolytic lesions.

Thrombocytosis occurs in at least 50% of patients. Patients may even be labeled as having essential thrombocytosis.3 In contrast to classic multiple myeloma, anemia is not a feature and mild erythrocytosis is present in about 20% of patients. With effective therapy, peripheral blood counts will normalize.

Papilledema is present in as many as 55% of patients.1–3 Patients are most commonly asymptomatic but may describe headache, transient obscurations of vision, scotomata, enlarged blind spots, and progressive constriction of visual field. Physical exam includes optic disc edema (usually bilateral) and blind spots.14

Pitting edema of the lower extremities is common. Ascites and pleural effusion occur in approximately one-third of patients.

Pulmonary hypertension, restrictive lung disease and impaired diffusion capacity of carbon monoxide may occur.13,15 Improvement of POEMS-associated pulmonary hypertension after therapy has been reported. The levels of tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, interleukin (IL)-1β, IL-6, and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) observed in these patients appeared to correlate with disease activity. In our recent transplant series, more than 90% of patients had abnormal pulmonary function tests. Restriction due to neuromuscular weakness was most common, followed by impaired diffusion capacity of carbon monoxide.

Both arterial and venous thromboses have been described in the setting of POEMS. In our series of 99 patients, there were 18 patients suffering serious events such as stroke, myocardial infarction, and Budd-Chiari syndrome.3 Lesprit et al reported that 4 of 20 POEMS patients had arterial occlusion.16 Additional patients have been reported to have gangrene, ischemia, myocardial infarction, splenic infarcts and strokes.

Renal dysfunction in POEMS syndrome is rare and nearly half of the patients with POEMS-associated renal dysfunction have co-existent Castleman disease. A total of 4 patients in our series developed renal failure as preter-minal events.3 Light chain deposition is not observed; instead, membranoproliferative features and evidence of endothelial injury are characteristic. On both light and electron microscopy, mesangial expansion, narrowing of capillary lumina, basement membrane thickening, sub-endothelial deposits, widening of the sub-endothelial space, swelling and vacuolization of endothelial cells, and mesangiolysis predominate.17,18

Pathogenesis

The cause of POEMS syndrome is unknown. It is tempting to incriminate the presence of lambda light chains in the pathogenesis because of their unexpected frequency (greater than 95% of cases), but histopathologic review of affected organs and nerves does not support that it is a form of deposition disorder.2,19 Soubrier et al have recently demonstrated restricted usage of Vγ1 genes in 2 patients with POEMS syndrome.20 Antibodies to human herpesvirus (HHV)-8 were reported in 78% of patients with POEMS syndrome and Castleman disease and in 22% of those with POEMS syndrome without Castleman disease.21

Increased levels of cytokines, more specifically VEGF, appear to play a pathogenic role in the disorder.22–26 Though patients frequently have higher levels of IL-1β, TNF-α, and IL-6 than patients with multiple myeloma,22 increased levels of VEGF are most frequently found and often decrease with successful therapy.27,28 VEGF induces an increase in vascular permeability and is important in angiogenesis. It is normally expressed by osteoblasts and it can be an important regulator of osteoblastic differentiation. One theory is that VEGF is secreted from plasma cells 27 and platelets 26 promoting vascular permeability, angiogenesis, monocyte/macrophage migration, potentially resulting in arterial obliteration. Hashiguchi has demonstrated VEGF release from aggregated platelets in patients with POEMS.26 VEGF could account for the organomegaly, edema, and skin lesions. The role it would play in the polyneuropathy is less clear, but descriptions of narrowed or closed lumina of endoneurial blood vessels raise the possibility of microthrombosis.27 Elevated levels of matrix metalloproteinases and tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases (TIMP) have been observed in patients with POEMS. Serum levels of VEGF and TIMP-1 were strongly correlated with each other. The significance of these findings are not yet fully understood but may lead to a better understanding of the pathogenesis of POEMS syndrome.29

Prognosis

The course of POEMS syndrome is chronic and patients’ median survival is about four times that of patients with classic multiple myeloma. At the Mayo Clinic 99 POEMS patients treated without peripheral blood stem cell transplantation had a median survival of 13.8 years;3 median survival has not yet been reached in our transplanted cohort (Figure 2 ).13 Individual reports of patients with the disease for many years are not unusual, and in one French study, at least 7 of 15 patients were alive for more than 5 years. These reports contrast with the original reports of median survivals of 12 to 33 months.2 The number of POEMS features does not affect survival (Figure 3 ).1,3

Relapse is possible in patients who have responded to therapy. In those patients with prolonged survival, additional features may arise over time.3 In the Mayo series 25/99 patients acquired new features of POEMS during follow-up. New features can develop more than a decade after initial presentation. The most common causes of death are cardiorespiratory failure, progressive inanition, infection, capillary leak-like syndrome, and renal failure.2,3 The neuropathy may be unrelenting and contribute to progressive inanition and eventual cardiorespiratory failure and pneumonia. Stroke and myocardial infarction, which may or may not be related to the POEMS syndrome, are also observed causes of death.

Treatment

There are no randomized controlled trials in patients with POEMS. Information about benefits of therapy is most typically derived retrospectively (Table 4 ). Given these limitations, however, there are therapies that appear to benefit patients with POEMS syndrome, including radiation therapy, alkylator-based therapies, and corticosteroids.3 Single or multiple osteosclerotic lesions in a limited area should be treated with radiation. If the patient has widespread osteosclerotic lesions, systemic therapy is necessary. In contrast to chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy, plasmapheresis and intravenous immunoglobulin do not produce clinical benefit. In appropriate candidates, peripheral blood stem cells should be collected before the patient has prolonged exposure to alkylating agents and high-dose chemotherapy with peripheral blood stem cell transplantation should be considered.13 If the selected therapy proves to be effective, response of systemic symptoms and skin changes tend to precede those of the neuropathy, with the former beginning to respond within a month and the latter within 3-6 months. We have seen patients who have continued to improve for 2 to 3 years after effective therapy.

Supportive Care

The physical limitations of the patient should not be overlooked while evaluating and/or treating the underlying plasma cell disorder. As always a multidisciplinary, thoughtful treatment program will improve a complex patient’s treatment outcome. A physical therapy and occupational therapy program is essential to maintain flexibility and assist in lifestyle management despite the neuropathy. In those patients with respiratory muscle weakness and/or pulmonary hypertension, overnight oxygen or continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) may be useful.

Radiation therapy

In those patients with a single, dominant osteosclerotic lesion, localized external beam radiation is generally considered to be first-line therapy.3,5 Solitary lesions, e.g., an osteosclerotic plasmacytoma with the associated paraneo-plastic syndrome of POEMS, should be treated like any other plasmacytoma because there is the potential for cure. Solitary plasmacytomas should be treated with doses of 40 to 50 Gy encompassing all disease with a margin of normal tissue. Non-neurological manifestations, such as hyperpigmentation, edema, hypertrichosis, gynecomastia, and hepatosplenomegaly, tend to improve more quickly than the neurological features.3,30 In our experience, more than half of patients treated with radiation will respond, and patients have excellent survival. Durable responses are possible.

Our group was the first to report the use of skeletal targeted radiation as part of the treatment strategy for patients with POEMS.31 153-Samarium-EDTMP was included as part of the conditioning regimen prior to peripheral blood stem cell transplantation in a patient with POEMS. Sternberg et al reported a case of a patient with POEMS who was treated with Strontium-89 after having failed one cycle of combination chemotherapy.32 This patient received 5 doses of Strontium-89 and prednisone. Though both patients did demonstrate clinical improvement, one cannot make any firm recommendations about the utility of skeletal targeted radiation therapy based on these two isolated reports.

Alkylator-based therapy

Cyclophosphamide as a single agent or in combination with prednisone can result in substantial clinical improvement in as many as 40% of patients.2,3 We typically use intravenous cyclophosphamide (with or without prednisone) in patients who are too sick to go immediately to transplantation or those who are rapidly deteriorating while awaiting approval for peripheral blood stem cell transplantation. Melphalan is among the most effective agents against plasmaproliferative disorders. Based on retrospective data approximately 40% of patients with POEMS syndrome will respond to melphalan and prednisone.3,33

Corticosteroids

No prospective studies support the use of corticosteroids in the treatment of POEMS syndrome, but case reports and personal observation would suggest that corticosteroids have activity.2,3 In our experience at least 15% of patients treated with single-agent corticosteroids experience clinical improvement and the disease is stabilized in another 7%. Therapy with corticosteroids should be considered temporizing rather than definitive therapy.

High-dose chemotherapy with hematopoietic stem cell transplantation

High-dose chemotherapy with peripheral blood stem cell transplant is an emerging therapy for patients with POEMS (Table 5). The first report was that of a 25-year-old female who was treated with high-dose chemotherapy followed by bone marrow transplantation; she died of multi-organ failure 63 days after her stem cell transplant.34 Subsequently, an additional 26 transplanted patients have been published (Figure 2B ).3,35–38 All patients have had improvement of their neuropathy over time. Other clinical features improved after stem cell transplantation, including levels of VEGF in several of the patients studied.35,37

We have observed that the transplant-related morbidity and mortality is higher in patients with POEMS than in patients with classic multiple myeloma. More than a third of our patients required mechanical ventilation. Though only 1 of our patients died (6.2% mortality rate), if the published experience of transplanted POEMS patients is pooled, the mortality figure is 2/27 or 7.4%.

New Agents

There is minimal experience using the newer agents thalidomide, lenolidomide, and bortezomib to treat POEMS. There is a theoretical rationale (anti-VEGF and anti-TNF effects) for using thalidomide or lenolidomide in these patients. There are anecdotal reports of beneficial application of thalidomide to patients with POEMS.39 Enthusiasm for its use in POEMS syndrome, however, should be tempered by the following: 1) thalidomide causes peripheral neuropathy in 20% of myeloma patients receiving the drug; 2) thalidomide has been shown to worsen fluid retention in patients with primary systemic amyloidosis;3 and 3) as a single agent, thalidomide is no more effective than oral alkylators in patients with plasma cell disorders. Because of the lesser neuropathic effect of lenolidomide, this agent may be of use in POEMS patients. Concerns about exacerbating the neuropathy also arises when contemplating bortezomib as a therapeutic option in these patients.

Other Therapies

Since the original diagnosis of patients with POEMS is often chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy, patients commonly receive immunomodulatory therapies including intravenous gamma-globulin, plasmapheresis, interferon-α, azathioprine, cyclosporine, or all-trans retinoic acid. In our experience, these drugs are not useful, but since they are commonly used with corticosteroids or radiation, it often difficult to elucidate their role.

Criteria for the diagnosis of POEMS syndrome.* (This research was originally published in Blood. Dispenzieri et al. POEMS syndrome: definitions and long-term outcome. Blood. 2003;101:2496–2506. © the American Society of Hematology)

| Abbreviations: POEMS, polyneuropathy, organomegaly, endocrinopathy, M protein, skin changes. | |

| *Two major criteria and at least 1 minor criterion required for diagnosis. | |

| †Osteosclerotic lesion or Castleman disease is almost always present. | |

| ‡Because of the high prevalence of diabetes mellitus and thyroid abnormalities, this diagnosis alone is not sufficient to meet this minor criterion. | |

| Major criteria | Polyneuropathy Monoclonal plasma cell-proliferative disorder |

| Minor criteria | Sclerotic bone lesions† Castleman disease† Organomegaly (splenomegaly, hepatome galy, or lymphadenopathy) Edema (edema, pleural effusion, or ascites) Endocrinopathy (adrenal, thyroid,‡ pituitary, gonadal, parathyroid, pancreatic‡) Skin changes (hyperpigmentation, hypertri chosis, plethora, hemangiomata, white nails) Papilledema |

| Known associations | Clubbing Weight loss Thrombocytosis Polycythemia Hyperhidrosis |

| Possible associations | Pulmonary hypertension Restrictive lung disease Thrombotic diatheses Arthralgias Cardiomyopathy (systolic dysfunction) Fever Low vitamin B12 values Diarrhea |

| Abbreviations: POEMS, polyneuropathy, organomegaly, endocrinopathy, M protein, skin changes. | |

| *Two major criteria and at least 1 minor criterion required for diagnosis. | |

| †Osteosclerotic lesion or Castleman disease is almost always present. | |

| ‡Because of the high prevalence of diabetes mellitus and thyroid abnormalities, this diagnosis alone is not sufficient to meet this minor criterion. | |

| Major criteria | Polyneuropathy Monoclonal plasma cell-proliferative disorder |

| Minor criteria | Sclerotic bone lesions† Castleman disease† Organomegaly (splenomegaly, hepatome galy, or lymphadenopathy) Edema (edema, pleural effusion, or ascites) Endocrinopathy (adrenal, thyroid,‡ pituitary, gonadal, parathyroid, pancreatic‡) Skin changes (hyperpigmentation, hypertri chosis, plethora, hemangiomata, white nails) Papilledema |

| Known associations | Clubbing Weight loss Thrombocytosis Polycythemia Hyperhidrosis |

| Possible associations | Pulmonary hypertension Restrictive lung disease Thrombotic diatheses Arthralgias Cardiomyopathy (systolic dysfunction) Fever Low vitamin B12 values Diarrhea |

Clinical features POEMS patients—three series.

| . | Mayo Series3 . | French Series1 . | Japanese Series2 . |

|---|---|---|---|

| . | %n=99 . | %n=25 . | %n=102 . |

| Abbreviations: NS, not stated | |||

| Comment: The percentage for all series uses the total number of patients in the series as the denominator | |||

| *Includes gonadal and adrenal abnormalities | |||

| **Of patients with bone lesions | |||

| This table was modified froma table originally published in Blood. Dispenzieri et al. POEMS syndrome: definitions and long-term outcome. Blood . 2003 ;101 :2496 –2506 | |||

| Peripheral neuropathy | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Organomegaly | 46 | NS | NS |

| Hepatomegaly | 25 | 68 | 78 |

| Splenomegaly | 22 | 52 | 35 |

| Lymphadenopathy | 26 | 52 | 61 |

| Endocrinopathy | 71* | NS | NS |

| Diabetes | 3 | 36 | 25 |

| Hypothyroidism | 17 | 36 | |

| Monoclonal plasma cell dyscrasia | 100 | 100 | 75 |

| Skin Changes | 68 | NS | NS |

| Hyperpigmentation | 46 | 48 | 93 |

| Acrocyanosis and plethora | 19 | NS | NS |

| Hemangioma/telangectasia | 9 | 32 | NS |

| Hypertrichosis | 26 | 24 | 74 |

| Thickening | 5 | 28 | 61 |

| Sclerotic bone lesions | 97 | 68 | 54 |

| Osteosclerotic only** | 47 | 41 | 56 |

| Mixed sclerotic and lytic** | 51 | 59 | 31 |

| Lytic only** | 2 | 0 | 13 |

| > 1 lesion** | 54 | 59 | 45 |

| Papilledema | 29 | 40 | 55 |

| Extravascular volume overload | 39 | NS | NS |

| Peripheral edema | 29 | 80 | 89 |

| Ascites | 15 | 32 | 52 |

| Pleural effusion | 9 | 24 | 35 |

| Castleman disease | 11 | 24 | 19 |

| Other features | |||

| Thrombocytosis | 54 | 88 | NS |

| Polycythemia | 18 | 12 | 19 |

| Clubbing | 5 | 32 | 49 |

| . | Mayo Series3 . | French Series1 . | Japanese Series2 . |

|---|---|---|---|

| . | %n=99 . | %n=25 . | %n=102 . |

| Abbreviations: NS, not stated | |||

| Comment: The percentage for all series uses the total number of patients in the series as the denominator | |||

| *Includes gonadal and adrenal abnormalities | |||

| **Of patients with bone lesions | |||

| This table was modified froma table originally published in Blood. Dispenzieri et al. POEMS syndrome: definitions and long-term outcome. Blood . 2003 ;101 :2496 –2506 | |||

| Peripheral neuropathy | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Organomegaly | 46 | NS | NS |

| Hepatomegaly | 25 | 68 | 78 |

| Splenomegaly | 22 | 52 | 35 |

| Lymphadenopathy | 26 | 52 | 61 |

| Endocrinopathy | 71* | NS | NS |

| Diabetes | 3 | 36 | 25 |

| Hypothyroidism | 17 | 36 | |

| Monoclonal plasma cell dyscrasia | 100 | 100 | 75 |

| Skin Changes | 68 | NS | NS |

| Hyperpigmentation | 46 | 48 | 93 |

| Acrocyanosis and plethora | 19 | NS | NS |

| Hemangioma/telangectasia | 9 | 32 | NS |

| Hypertrichosis | 26 | 24 | 74 |

| Thickening | 5 | 28 | 61 |

| Sclerotic bone lesions | 97 | 68 | 54 |

| Osteosclerotic only** | 47 | 41 | 56 |

| Mixed sclerotic and lytic** | 51 | 59 | 31 |

| Lytic only** | 2 | 0 | 13 |

| > 1 lesion** | 54 | 59 | 45 |

| Papilledema | 29 | 40 | 55 |

| Extravascular volume overload | 39 | NS | NS |

| Peripheral edema | 29 | 80 | 89 |

| Ascites | 15 | 32 | 52 |

| Pleural effusion | 9 | 24 | 35 |

| Castleman disease | 11 | 24 | 19 |

| Other features | |||

| Thrombocytosis | 54 | 88 | NS |

| Polycythemia | 18 | 12 | 19 |

| Clubbing | 5 | 32 | 49 |

Clinical and laboratory features of plasma cell dyscrasia-associated peripheral neuropathy.

| Characteristic . | MGUS . | POEMS . | Multiple Myeloma . | AL Amyloidosis . | Cryoglobulinemia . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abbreviations: MGUS, monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance; BM, bone marrow. | |||||

| Reprinted with permission from Dispenzieri A. Suarez GA. Kyle RA. POEMS syndrome (osteosclerotic myeloma) In: Dyck PJ. Thomas PK, eds. Peripheral Neuropathy 4th edition. Philadelphia: Elsevier Saunders; 2005:2453–2469.40 | |||||

| Peripheral neuropathy | ~5% | 100% | 1%–8% | 15%–20% | ~25% |

| Sensory versus motor predominance | Sensory, ataxia (IgM) sensorimotor | Predominantly motor | Sensory | Sensory sensorimotor | Predominantly sensory |

| Organomegaly | – | ++ | + | ++ | ++ |

| Skin involvement | – | ++ | + | + | +++ |

| Other symptoms | Asymptomatic | Edema, fatigue, endocrine abnormalities | Bone pain, fatigue, infections | Fatigue, edema, cardiomyopathy, nephrosis | Purpura, arthralgia, hepatitis, nephritis |

| Monoclonal heavy chain | IgM >IgG >IgA | IgG > IgA >IgM | IgG > IgA | IgG > IgA > IgM | IgM >> IgG > IgA |

| Monoclonal light chain | Kappa 75% of cases | Lambda > 95% of cases | Kappa 75% of cases | Lambda 75% of cases | Kappa 75% of cases |

| Serum M-spike, gm/dL | < 3 | Usually < 2 | Usually > 3 | Usually < 2 | Usually < 2 |

| BM plasma cells, % | < 10 | Usually < 5 | > 10 | Usually < 10 | Usually < 5 |

| Skeletal lesions | – | +++ (sclerotic, mixed sclerotic & lytic) | +++ (lytic, osteoporotic, or fracture) | – | – |

| Thrombocytosis | – | ++ | - | + to ++ | + |

| Anemia | - | + | ++ | + | ++ |

| Characteristic . | MGUS . | POEMS . | Multiple Myeloma . | AL Amyloidosis . | Cryoglobulinemia . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abbreviations: MGUS, monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance; BM, bone marrow. | |||||

| Reprinted with permission from Dispenzieri A. Suarez GA. Kyle RA. POEMS syndrome (osteosclerotic myeloma) In: Dyck PJ. Thomas PK, eds. Peripheral Neuropathy 4th edition. Philadelphia: Elsevier Saunders; 2005:2453–2469.40 | |||||

| Peripheral neuropathy | ~5% | 100% | 1%–8% | 15%–20% | ~25% |

| Sensory versus motor predominance | Sensory, ataxia (IgM) sensorimotor | Predominantly motor | Sensory | Sensory sensorimotor | Predominantly sensory |

| Organomegaly | – | ++ | + | ++ | ++ |

| Skin involvement | – | ++ | + | + | +++ |

| Other symptoms | Asymptomatic | Edema, fatigue, endocrine abnormalities | Bone pain, fatigue, infections | Fatigue, edema, cardiomyopathy, nephrosis | Purpura, arthralgia, hepatitis, nephritis |

| Monoclonal heavy chain | IgM >IgG >IgA | IgG > IgA >IgM | IgG > IgA | IgG > IgA > IgM | IgM >> IgG > IgA |

| Monoclonal light chain | Kappa 75% of cases | Lambda > 95% of cases | Kappa 75% of cases | Lambda 75% of cases | Kappa 75% of cases |

| Serum M-spike, gm/dL | < 3 | Usually < 2 | Usually > 3 | Usually < 2 | Usually < 2 |

| BM plasma cells, % | < 10 | Usually < 5 | > 10 | Usually < 10 | Usually < 5 |

| Skeletal lesions | – | +++ (sclerotic, mixed sclerotic & lytic) | +++ (lytic, osteoporotic, or fracture) | – | – |

| Thrombocytosis | – | ++ | - | + to ++ | + |

| Anemia | - | + | ++ | + | ++ |

Response to therapy in patients 2ith POEMS syndrome.

*Includes vincristine, carmustine, melphalan, cyclophosphamide, and prednisone; vincristine, Adriamycin, and dexamethasone; cyclophosphamide, Adriamycin, vincristine, and prednisone; and cyclophosphamide-based chemotherapy.

† Sixty-four patients were treated with 70 courses of radiation.

This research was originally published in Blood.

Response after peripheral blood stem cell transplantation (PBSCT) (median follow-up 10.8 months).*

| . | N . | Response, % . | Stable, % . | Not Evaluated, % . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| * 1 died before evaluation and 1 too soon to evaluate | ||||

| † One patient showed borderline worsening at 15 months, but at 24 months, patient reported substantial improvement; no repeat neuropathy impairment score was performed. | ||||

| ‡ 2 complete responses, 3 very good partial response, and 1 minimal response | ||||

| This research was originally published in Blood. Dispenzieri et al. POEMS Syndrome: Definitions and Long-term Outcome. . © by the American Society of Hematology. Blood . 2003 ;101 :2496 –2506 | ||||

| Neurologic | 16 | 87 | … | 13 |

| Subjective | 16 | 87 | … | 13 |

| Nerve conduction studies (at 1 yr) | 11 | 36 | 9 | 55 |

| Neuropathy impairment score | 16† | 25 | 12 | 56 |

| Hematologic | 16 | 56 | 6 | 37 |

| Non-secretory | 3 | NA | NA | 100 |

| Immunofixation only | 7 | 43 | 14 | 43 |

| Serum protein electrophoresis (SPEP) evaluable | 6 | 100‡ | … | … |

| Organ | 11 | 82 | … | 18 |

| Hepatomegaly | 5 | 60 | … | 40 |

| Splenomegaly | 10 | 50 | 20 | 30 |

| Lymphadenopathy | 7 | 71 | 29 | 0 |

| Extravascular volume overload | 14 | 79 | … | 21 |

| Ascites | 6 | 83 | … | 17 |

| Effusion | 4 | 100 | … | … |

| Edema | 14 | 79 | … | 21 |

| Skin changes | 13 | 54 | 15 | 31 |

| Papilledema | 4 | 50 | … | 50 |

| Endocrine | 13 | 23 | 8 | 69 |

| Pulmonary | 15 | 20 | … | 80 |

| . | N . | Response, % . | Stable, % . | Not Evaluated, % . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| * 1 died before evaluation and 1 too soon to evaluate | ||||

| † One patient showed borderline worsening at 15 months, but at 24 months, patient reported substantial improvement; no repeat neuropathy impairment score was performed. | ||||

| ‡ 2 complete responses, 3 very good partial response, and 1 minimal response | ||||

| This research was originally published in Blood. Dispenzieri et al. POEMS Syndrome: Definitions and Long-term Outcome. . © by the American Society of Hematology. Blood . 2003 ;101 :2496 –2506 | ||||

| Neurologic | 16 | 87 | … | 13 |

| Subjective | 16 | 87 | … | 13 |

| Nerve conduction studies (at 1 yr) | 11 | 36 | 9 | 55 |

| Neuropathy impairment score | 16† | 25 | 12 | 56 |

| Hematologic | 16 | 56 | 6 | 37 |

| Non-secretory | 3 | NA | NA | 100 |

| Immunofixation only | 7 | 43 | 14 | 43 |

| Serum protein electrophoresis (SPEP) evaluable | 6 | 100‡ | … | … |

| Organ | 11 | 82 | … | 18 |

| Hepatomegaly | 5 | 60 | … | 40 |

| Splenomegaly | 10 | 50 | 20 | 30 |

| Lymphadenopathy | 7 | 71 | 29 | 0 |

| Extravascular volume overload | 14 | 79 | … | 21 |

| Ascites | 6 | 83 | … | 17 |

| Effusion | 4 | 100 | … | … |

| Edema | 14 | 79 | … | 21 |

| Skin changes | 13 | 54 | 15 | 31 |

| Papilledema | 4 | 50 | … | 50 |

| Endocrine | 13 | 23 | 8 | 69 |

| Pulmonary | 15 | 20 | … | 80 |

Clinical features present at diagnosis in 99 patients with POEMS seen at the Mayo Clinic from 1975 to 1998.3

Abbreviations: PCD, plasma cell dyscrasia.

Clinical features present at diagnosis in 99 patients with POEMS seen at the Mayo Clinic from 1975 to 1998.3

Abbreviations: PCD, plasma cell dyscrasia.

Overall survival.

Overall survival in 99 patients receiving conventional dose chemotherapy. This research was originally published in Blood.

Dispenzieri et al. POEMS syndrome: definitions and long-term outcome. Blood. 2003;101:2496–2506.© by the American Society of Hematology.After peripheral blood stem cell transplant. Published world experience including 16 Mayo patients and 11 previously reported patients.35–38

This research was originally published in Blood.

Overall survival.

Overall survival in 99 patients receiving conventional dose chemotherapy. This research was originally published in Blood.

Dispenzieri et al. POEMS syndrome: definitions and long-term outcome. Blood. 2003;101:2496–2506.© by the American Society of Hematology.After peripheral blood stem cell transplant. Published world experience including 16 Mayo patients and 11 previously reported patients.35–38

This research was originally published in Blood.

Survival on the basis of number of features at presentation in 99 patients.

MS, median survival; Pts, patients. Bardwick-5 includes polyneuropathy, organomegaly, endocrinopathy, monoclonal plasma cell disorder, and skin changes. Mayo-9 includes all the features of Bardwick-5 as well as sclerotic bone lesions, Castleman’s disease, extravascular volume overload, and papilledema.

This research was originally published in Blood.

Survival on the basis of number of features at presentation in 99 patients.

MS, median survival; Pts, patients. Bardwick-5 includes polyneuropathy, organomegaly, endocrinopathy, monoclonal plasma cell disorder, and skin changes. Mayo-9 includes all the features of Bardwick-5 as well as sclerotic bone lesions, Castleman’s disease, extravascular volume overload, and papilledema.

This research was originally published in Blood.

From the Division of Hematology and Internal Medicine, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN

Supported in part by the Hematologic Malignancies Fund, Mayo Clinic.