Abstract

Psychosocial domains and palliative care medicine are the connective tissue of our fragmented health care system. The psychosocial domains of palliative care are central to creating new partnerships with physicians, patients, and their caregivers in emotionally charged medical environments, especially Intensive Care Units. Managing the psychological, social, emotional, spiritual, practical and existential reactions of patients and their loved ones supports effective action and problem-solving. Practical aspects to establishing realistic goals of care among the health care team and other specialists, communicating effectively with patients and families in crisis, using the diverse and ambiguous emotional responses of patients, families, faculty and staff therapeutically, and helping to create meaning in the experience is essential to whole-patient and family care centered. The family conference is an excellent vehicle to create an environment of honest and open communication focused on mobilizing the resources of the patient, family and health care team toward a mutually agreed upon plan of action resulting in clearly defined goals of care.

Palliative Care and Psychosocial Contributions in the ICU

There is increasing consensus that ICU admission benefits patients with hematologic malignancies, including bone marrow transplant patients.1–3 Moreover, there is evidence that patients with stage 4 disease, who are most likely to require ICU admission, are subject to high levels of distress. In the ICU, complex medical decisions collide with a highly emotionally charged environment and entrenched patterns of communication in families as well as the health-care team that intensify distress for the patient, family, and healthcare team. Because of these realities, patients and families in the ICU require a comprehensive approach that includes attention to the physical, psychological, social, practical and spiritual/existential aspects in the service of active coping and problem solving. This approach is enhanced by the utilization of the palliative care team who have the skills and time to deliver whole-patient care in the context of a family unit. A key tool utilized by the palliative care team to optimize communication and optimize the delivery of compassionate care focused on quality of life is the family conference. It is an effective tool to engage and emotionally support patients and families in order to provide timely information and to establish goals of care. The most effective family conferences require several elements: (1) a pre-conference meeting of healthcare providers to reach consensus on the medical details and proposed course of action, and (2) skilled facilitation of the family meeting. This facilitation elicits patient and family values and goals and appropriately utilizes the patient’s primary physician and the intensivist to establish realistic goals of care focused on quality of life.

Introduction

Despite the growth of palliative care and psychosocial programs, supportive care services for patients and families in the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) are neither adequate nor at the same standard as the medical and nursing services provided.4 In a comprehensive review of the literature, it was found that there are still large educational gaps among physicians, nurses, social workers, patients and families relating to palliative care.5 Although it is now generally accepted that many patients can be kept alive indefinitely in a state of the art critical care or ICU, the decision-making processes manifested by emotionally overwhelmed and confused families also creates distress in the committed health care professionals who care for them. Of the over 500,000 annual deaths in the United States, 1 in 5 occur in an ICU.6 Intensive care units focus on state of the art technology and advanced medical and nursing care. Patients are often unable to communicate because of intubation or medical problems. Yet, in many circumstances, the greatest challenge to humane and appropriate care for critically ill patients relates to psychosocial adjustment and not the technological ability to prolong life, manage physical symptoms or to maximize comfort.7 In fact, in a random national survey of 600 ICU directors, with a response rate of 78% (N = 468), Nelson et al identified the top ten challenges to providing care in the ICU:

Unrealistic patient and family expectations

Patients unable to participate

Insufficient staff training in communication

Competing demands on physicians

Lack of advance directives

Disagreement within families

Inadequate ICU-family communication

Fear of legal liability

Unrealistic clinician expectations

Suboptimal space for family meetings

None of the top 10 problems were related to medical or nursing care. Almost all of these problems can be ameliorated by the presence of comprehensive palliative care services.8 This finding has significant implications for safety, quality, patient and family satisfaction and for the quality of life for patients, their families and as significantly for the health care staff. Yet referrals to palliative care teams from ICUs and from hematological services where morbidity, mortality and emotional distress are especially high are consistently reported to be lower than from other specialties including solid tumor services.9 Although there have been improved survival rates in patients with hematological malignancies admitted to the ICU,10 which may account at least in part for the relatively small number of referrals for palliative care services, the symptom burden for hematological patients is high and may be more suited to a model that includes an integrated approach that combines investigational and disease-directed approaches with palliative care. Within the model of simultaneous care, palliative care is provided throughout the treatment spectrum, focusing on the inherent strengths of the patient and the family, exquisite symptom management, psychosocial and spiritual support, communication, and quality of life.11

Integrated palliative care and psychosocial programs have been identified as models to be replicated by the Institute of Medicine (IOM) given the needs of patients and family members for a patient-centered approach to care.12 Palliative care is more than symptom management. The IOM Report (1997), defines palliative care as “…prevention and relief of suffering through the meticulous management of symptoms from the early, through the final Stages of an illness. Palliative care attends to the emotional, spiritual and practical needs of patients and those close to them.”13 The provision of carefully integrated medical and psychosocial care is the core of whole-patient care. Palliative care is always delivered by teams. The core palliative care team is comprised of a board certified palliative care physician, nurse and social worker. Psychiatrists, psychologists, spiritual care counselors and pharmacists are also essential resources.14 For patients, family members and the healthcare teams, palliative care medicine with its whole-person perspective is the much-needed connective tissue of a highly technical and fragmented healthcare system.

Psychosocial aspects of palliative care in the ICU focus on quality of life for critically ill patients, their families and health care staff by maximizing the psychological, social, practical, spiritual/existential resources and strengths as individual domains and as highly interactive reinforcing systems. Psychosocial care also extends to those patients and families who manifest significant levels of distress, thereby requiring specialized and tailored interventions. The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) defines distress as, “An unpleasant emotional experience of a psychological, social and/or spiritual nature which extends on a continuum from normal feelings of vulnerability, sadness and fears to disabling problems such as depression, anxiety, panic, social isolation and spiritual crisis.”15 Although high levels of disabling distress are present in about 33% of cancer patients overall, rates among patients with advanced disease or those experiencing acute medical crises are much higher.16

Stage IV Cancer Patients Have More Distress

While at the University of California, San Diego NCI Designated Comprehensive Moores Cancer Center, our team screened over 2000 consecutive cancer outpatients by diagnosis, staging, age and gender for problem-related distress known to be common to the cancer experience. The instrument, How Can We Help You and Your Family?17 consists of 36 problem-related distress questions. For each question, patients are asked to rate the severity of the problem on a scale from 1 to 5, with 1 indicating it is “Not a Problem At All To Me” through 5 indicating it is the “Worst Problem I Could Have.” In addition, patients are asked to circle “Yes” if they would like to discuss the problem with a member of the staff. A secondary analysis of this data was conducted on a subset of patients with staging data. A total of 505 patients had staging data; however, patients staged as a Stage 0 (n = 41) were excluded in this analysis. Thus, 464 patients had Stage 1 through Stage 4 disease. Since the focus of this chapter is the contribution of palliative care and psychosocial aspects in the ICU, patients were separated into two comparison groups: Stage 4 disease (n = 110) and Stages 1, 2 and 3 disease (n = 352). Patient demographics by Stage groups are presented in Table 1 . There were no significant differences in age, race or relationship status between the groups; however, there were significantly more males (58.7%) with Stage 4 disease than females (41.3%), P < .01, with a reverse trend of significantly more females (67.3%) with Stages 1, 2 and 3 disease than males (32.7%), P < .01. Gender was controlled for in the statistical comparisons of this data.

All 36 questions of the How Can We Help You and Your Family? screening instrument are listed by Stage in Table 2 in descending order based on the percentage of Stage 4 patients who rated that problem ≥ 3. Table 2 also shows the percentages of respondents who requested to speak to a member of the staff for each problem by circling “Yes.” Based on the percentage of people who reported ≥ 3 for a particular problem, the five most common causes of problem-related distress for Stage 4 patients were fatigue (53.8%), pain (44.2%), sleeping (44.2%), finances (41%) and understanding my treatment options (39%). For Stages 1, 2 and 3 patients fatigue (40.6%), sleeping (32.4%), pain (28.4%), me being dependent on others (27.10%) and feeling down depressed or blue (26.4%) were the top five rated problems ≥ 3. As displayed in Table 2 the frequencies of problems rated ≥ 3 for Stage 4 patients were higher for all problems than in Stages 1, 2 and 3 patients except for someone else totally dependent on me for their care and talking with family, children and friends, which were only slightly higher for Stages 1, 2 and 3 patients. To further understand the magnitude of these differences in problem-related distress rated ≥ 3 between the Stage groups a difference score was computed by taking the percentage of problem-related distress rated ≥ 3 reported by Stage 4 patients and subtracting the percentage of problem-related distress rated ≥ 3 reported by Stages 1, 2 and 3 patients (Table 2 ). The largest discrepancy in reported problem-related distress rated ≥ 3 was understanding my treatment options, which was rated 17.2% more frequently for Stage 4 patients than Stages 1, 2 and 3 patients. Pain (15.8%), finances (15.1%), recent weight change (14.4%), and fatigue (13.2%) were also in the top five difference scores in problem-related distress rated ≥ 3, with Stage 4 patients reporting higher levels of distress than in Stages 1, 2, and 3 patients.

In terms of the percentages of patients by Stage groups who requested to speak to a member of the staff by circling “Yes,” the five most common problems circled “Yes” for Stage 4 patients were as follows. The top 4 were understanding my treatment options, finances, sleeping, pain, and tied for fifth were finding community resources near where I live, needing someone to help coordinate my medical care and feeling down depressed or blue. For Stages 1, 2 and 3 patients, the trend was the same; however, needing someone to help coordinate my medical care and feeling down depressed or blue were not ranked equal to the 5th most common problem in terms of the frequency of circling “Yes.”

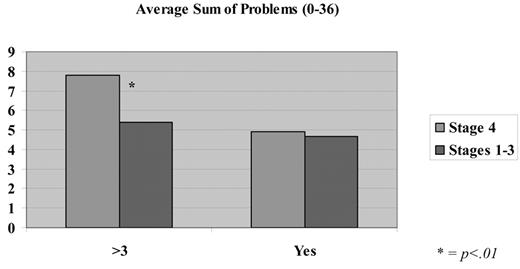

As presented in Loscalzo and Clark17 an overall problem-related distress score was created by summing all the problems rated ≥ 3, scores range from 0 to 36. Higher overall problem-related distress scores indicate a greater number of individual problems reported ≥ 3. An additional sum score was created to determine if there were any differences between the Stage groups in the number of problems that were circled “Yes” requesting to speak to a member of the staff. The score was computed by summing all the “Yes” responses, yielding a score ranging from 0 to 36. Higher overall scores indicate a greater number of problems that were requested to speak to a member of the staff. The average sum scores by Stage groups are presented in Figure 1 . When controlling for gender, Stage 4 patients reported significantly more problems rated ≥ 3 than Stage 1, 2 and 3 patients, P < .01. However, there were no significant differences in the number of “Yes” responses by Stage groups.

As reported in the literature and in the data presented above, both the number of problems overall, as well as the level of distress related to the problems endorsed, add burden to the patients and families as they attempt to integrate complex and ambiguous information, manage intense emotions, make life-focused decisions, distribute family resources, and cope with the ongoing demands of work and daily living. As displayed in the data above, patients in Stage 4 (patients most likely to be in the ICU18) are at higher risk of problem-related distress than patients in Stages 1, 2 and 3 combined. Thus these patients have even more added burden to manage. Although these stressors occupy much of the psychic energy available to patients and families, the fear and anxiety related to the specter of potential loss of life is always just beneath the surface of daily activities. The “out-of-proportion” emotions that are expressed through less threatening events such as the quality of the food, parking, or the warmth of the staff are frequently expressions of this underlying reality that the life of a loved one is threatened and that control of what matters most to them is beyond their reach.

No one would question the importance of managing patients’ distress and suffering. Yet considerable evidence indicates that distress goes unrecognized by medical oncologists19 and that high levels of distress are related to lower quality of life,20 decreased adherence to recommended treatments,21 and poorer satisfaction with medical care overall.22 Fortunately, as noted in the recent IOM Report, there is strong evidence that once distress is identified it can be effectively managed with existing pharmacologic and non-pharmacologic interventions and resources.12 When physical and psychological symptoms are poorly managed in patients, family members and health care staff experience secondary distress that undermines effective emotional management, communication, effective problem-solving and safety right at the time when a sense of order and control are needed most.

Patients, Families and the ICU

Within the goals of palliative care, the uniquely psychosocial aspects of care seek to minimize vulnerability by supporting the efforts of patients, families and healthcare staff to experience as much control and predictability in their immediate situation as possible, while encouraging a deep sense of connection toward common goals and ultimately the creation of meaning that transcends the immediate challenge. When patients and families feel that the health care team has acted in their best interests, has provided the best care possible, has been honest and specific in their recommendations, and respected their process of decision-making, the sense of satisfaction and meaning, even or especially, in the face of death, is shared by all constituents. But ultimately, for the patients in the ICU and their concerned families, being confronted with the real possibility of death is primarily an emotional experience, not a technological one, with life altering implications for the present and the future based on a past that permeates all communication and decision making.

The highly charged emotional environments of ICUs resulting from the life or death context, complexity of specialized medical care, intimidating technology, hyper vigilance to detail, sense of isolation and the constant threat of potential errors creates a sense of controlled-terror in many patients and families and potential exhaustion in health care professionals. The ICU is an unnatural environment where forced inter-dependencies on strangers are as real for the patients and families as they are for the staff. The imminent threat to life and the need to rapidly integrate cognitively and emotionally complex and ambiguous information, leading to decision-making of great importance, are superimposed on patients and families needing to divulge highly personal information, family processes, shifts in power hierarchies and the need to alter long-held communication patterns with people they do not know. For many patients and families, time confined in the ICU is experienced as too fast to manage and yet too slow to pass, a sanctuary and a threat simultaneously. For the staff trying to best support patients and families these mixed emotional experiences can be confusing and frustrating. For example, it has been reported that approximately one-third of ICU nurses experienced burn-out syndrome.23 In a survey of 1000 practicing oncologists, Whippen et al found that more than half reported burn-out syndrome.23 This is especially true where the expectations and goals of the health care team are at odds with patients and families. Even the most concerned, engaging and committed health care team cannot truly know the family history and experiences that shape the responses of patients and families. For most patients and families, this may be the hardest problem they have ever had to manage in their lives. For health care staff, negotiating the psychosocial demands of the families may be experienced as much more stressful than the complex medical management of patients.

Families are like countries, each with their own boundaries, language, power hierarchy and rules. Serious illness is always stressful and life-threatening illness is almost always a crisis. Families respond to serious threats in different but relatively predictable ways on a continuum. Family boundaries are important because they reflect the adaptability and flexibility to be able to use health care professionals and other external resources without undermining the structure of the existing family. For those families who have extreme, very rigid (impermeable) boundaries or those with little or very weak boundaries (permeable), medical crises will be highly disruptive within the family and their interactions with health care staff will be stressful. In either of these extremes, staff may feel like they are being pulled into the family network without regard to the situation in ways that makes them feel manipulated or at the other extreme staff may be kept at arm’s length at all times making communication and joint problem-solving difficult. Zabora et al demonstrated that families who are at the extremes create more conflict with hospital staff and have higher levels of distress.24

For the majority of families who are able to work closely with health care professionals, tolerate the forced-dependency and maintain the integrity of their changing family structure, there will be a flexible give and take that supports joint decision making. For the health care teams staffing ICUs, every bed is another story, challenge and opportunity. Because of the ongoing stress of the ICU environment, it should be expected that from time to time health care professionals will reflexively respond to intense situations from their own historical family experiences. If the health care professional is able to identify the counter-transference, it can lead to a more informed and empathetic response to the patient and family situation. There will also be a greater sense of control experienced. If emotional responses of the health care professional to a patient or family are not understood or are not based in the here and now, there can be increased stress, frustration and confusion for all involved. Although the emotional responses of ICU patients, families and health care professionals are inextricably linked to each other in ways not apparent in less-stressful medical environments, there are no known studies that attempt to align the strengths of these inter-dependent constituents. Given the wide variety of coping responses and communication styles in patients, families, and health care professionals, especially as they relate to age, gender, educational levels and culture, studies of this type are difficult to design and implement.

The call for enhanced systematic approaches to support and engage patients and families in their decision making at the end of life has received considerable attention.25 A comprehensive assessment of the patient’s medical and psychosocial situation, elicitation of patient and family values and goals, open and honest communication around prognosis, risk-benefit ratios of all reasonable options and clear recommendations by the physician couched in terms of patient and family values and goals are the foundation for sound decision-making leading to consensus around goals of care. There are many readily available educational instruments to teach physicians how to share bad news.26 But sharing bad news is not the same as asking a family to make active decisions around goals of care that affect a loved one. Abbott et al interviewed bereaved families one year after the discussion of withdrawal or withholding life sustaining support and found that 46% of the bereaved families reported conflict during the ICU stay related to communication and staff behavior. Families also reported the importance of having a family conference room available and active participation by the attending physician in decision making.27 However, there is a dearth of information available about how physicians and health care providers can use palliative care and psychosocial services in the ICU. One way to support better and more informed interactions between patients, families and health care staff is to create ongoing opportunities to work together on common concerns and problems related to the patient’s situation. The family conference provides such an opportunity.

The Family Conference—Establishing Goals of Care

The enforced time and emotional intensity of the ICU and the close physical proximity of patients, families and health care staff create a unique opportunity for team work. In a survey of 78 ICUs, Azoulay et al found that although there was strong agreement (88.2%) by health care professionals that family members should be actively included in the physical caring for their loved ones in the ICU, only 33.4% of the family members wanted to participate.28 It appears that family members perceive there to be clear boundaries between what they are willing and capable of doing for their loved ones and what the health care staff must control. The intimidating technology, noise, crowded space, sense of seriousness and perceived fragility of life in the ICU does not lend itself to family members feeling able to take on duties that engender additional fear. For many patients and families with extended stays in the ICU, all of their diminishing psychic resources are invested in controlling their fears, powerlessness and sadness. This is in large part why patients and family members have such an insatiable desire for ongoing information, even if it is redundant, and to know the next steps; in other words, what is the plan of action and what do we do now? There is a need for an organized approach that must include the leadership of the health care professionals, patients (whenever possible), families and concerned others working together to agree upon the goals of care. Control, predictability, connection and meaning enable patients and families to manage their fears, focus their energies and to take meaningful action together, with the essential guidance and encouragement of health care team. The family conference can provide the context for an open and honest discussion for goals of care.

The family conference in the setting of the ICU has been shown to enhance communication, quality of care, impact length of stay, and to have important supportive implications for health care staff.29,30 Although family conferences are quite common in ICUs, the professionals leading these meetings are seldom trained in understanding family systems, facilitating group process, fostering open and honest communication or counseling. Fortunately, there are models of education for professionals that have been shown to be effective.31 Von Gunten et al in particular have pioneered innovative physician education programs to master communication at the end of life.32 The family conference is a core value and intervention for the palliative care team.

Preparing for the Family Conference to Establish Goals of Care

One of the most important parts of the family conference is the pre-family conference meeting with the treating and ICU physicians, a nurse well versed in the patient’s daily care and the facilitator. This usually takes about 20 minutes and may be done on the telephone. The pre-meeting is to establish agreement on basic medical and psychosocial information and to establish clearly stated recommendations.

If there is conflict between the physicians, this is the time for open and honest discussion to reach an agreement about what is in the best interests of the patient and the family. Common conflicts around goals of care that surface during the pre-family conference generally relate to highly complex medical situations with ambiguous data, physicians having difficulty accepting the reality of the medical situation of long-term patients and their families with whom they have an emotional bond, or the inability to accept the reality of the situation due to potential narcissistic injury. Palliative Care teams or Ethics Committee members may be engaged at this time to clarify the areas of disagreement and to reach a resolution. When at all possible, it is best that the family be given the same clear recommendations from all of the members of the health care team. In those unusual situations, where there is a lack of consensus the time in the pre-family conference meeting is spent organizing the information so that the family can understand the complexity of the situation. It is the facilitator’s leadership role in the pre-family conference meeting to explain and role-model how the family conference will be organized and how decisions will be achieved.

Meeting with the Family about Goals of Care

The family conference has been shown to be an effective way to get patients (when they are able to participate) and families to discuss emotionally charged topics and to make difficult decisions. Clearly, the most stressful of which is the decision to stop futile life-sustaining treatments for a beloved family member. By eliciting the values and goals of the family in an honest and open setting in which there is adequate time to share emotions and to discuss difficult topics, the connections between the wishes expressed and the medical recommendations made will create an environment of trust. Family conferences are helpful to the family because the information shared by the health care team is heard by everyone at the same time. Family members highly value the opportunity to ask questions of the physicians and others. The added support and presence of family members makes it easier to ask difficult questions and to hear the emotionally charged information. There is also the opportunity for expressions of grief, such as crying, and for manifestations of emotional support through touching and verbal expressions of love in a supportive environment. For some family members this may be the first time they have allowed themselves to think about the reality of the situation. If the patient is high up in the family hierarchy, the family conference may start the process of realignment to a new family power structure. It is at this point that family conflict may arise around decision making. For most families, however, the desire to do what is best for the patient encourages cooperation and team work. If there are influential family members who are not able to attend the family conference, it is essential to have them participate in any way possible in the family conference. This may be achieved by the use of a high quality speaker telephone. It may be necessary for the health care team to insist that the family members make themselves available. This may mean meeting after business hours or requesting that family members take time away from work.

The primary goals for the family conference are to insure that the wishes of the patient are being respected, that the family is aware of those wishes, that the family recognizes that everything that should be done is being done, and that the family is doing the best they can. It is very helpful for there to be minutes of the family meeting to share among themselves. By consistently reviewing the minutes with the family throughout the meeting trust and communication is enhanced. This gives the family the opportunity to correct what they may perceive as any inaccuracies in their wishes. This process also gives the family another opportunity to hear out loud and to cognitively integrate, in a supportive setting, the reality of the situation. Although the facilitator may also be the minute taker, this duty is best managed by another heath care professional if one is available. Although the minutes are always in writing, audio taping the major decisions made can also be helpful to the family to review later and to share with other family members who may not have attended the meeting. At the end of the meeting, the minutes should be read back aloud one more time and any changes made at that time. The facilitator can then make copies for all present and for the medical record.

The family conference usually takes 1 to 3 hours. This is a long time but allows for the discussion of relevant medical data, integration of complex information, emotional expression and support in response to the implications of the information shared and agreement on an initial plan of action. Due to the nature of the information to be discussed, it is important to have a private and quiet area where interruptions will be minimized. The facilitator of the family conference should clearly state the reason for the meeting and desired outcomes at the beginning. For example, the facilitator might say, “we are here today to understand your loved one’s values and goals, discuss the present medical situation of your loved one, what is going on with them physically now, the implications of the situation (especially prognosis), and to make informed and realistic decisions together about next steps based on the physician’s recommendations.”

Key Role of the Attending Physician in the ICU

The attending physician is the person the patient and family know best. Once admitted to the ICU, the patient and family may feel lost and confused by having to learn a new system and to adjust to the culture of the ICU. There are times when the relationship between attending physician and family leads to an open and honest discussion of goals of care for a patient who cannot speak for themselves. When the attending physician has the time, skills and motivation to help families make difficult decisions this may be the best of situations. However, many times the attending physician is imbued with supernatural powers by the families and is associated with disease-directed life-prolonging treatments that make it difficult to implement the mental shift to accepting the reality of imminent death.

In most circumstances in the ICU, the role of the attending physician is crucial to setting the Stage and laying the foundation for the work to be done by indicating honestly and openly, in simple language, the present medical situation, the most-likely imminent course of events and to make a recommendation in the context of the patient’s values and goals. Asking the family to make medical decisions can lead to an exaggerated sense of responsibility, and secondary trauma that can have life-long consequences. The attending physician must tell the family that they have done everything that could reasonably be done and then make recommendations as to next steps. In our experience, it is best if the attending physician then either leaves the room or clearly and definitively turns the meeting over to the facilitator. If this does not happen, the discussion will seldom get beyond the endless intellectual medical nuances and details and “what ifs” of the situation, which confuses rather than clarifies, immobilizes rather than mobilizes. Also, because the attending physician may have known the patient and family for a long time or because the family is highly emotional, the attending physician may waver and revert to the comfort zone of treatment options and begin to give ambiguous responses that will cause increased conflict and create confusion within the family conference. Mixed signals can undermine the cohesiveness of the family at a time when they will need to have all of their psychic and spiritual resources as closely aligned as possible. If the attending physician decides to leave the family conference, the facilitator can always call the attending physician on the telephone to provide additional information or to come back to the meeting if their presence becomes necessary. Within the context of goals of care, the attending physician has the key role to play in framing the medical situation, making specific recommendations for ongoing medical management and for handing the meeting off to the facilitator to support the family in their emotional management and decision making.

The Facilitator of the Family Conference

The facilitator must be committed to doing what is in the best interests of the patient and family, have superb communication skills, be an expert in running family conferences, understand group work processes, have training in family dynamics and be highly skilled in focusing highly-charged emotional responses into meaningful activity. Generally, a licensed mental health professional or board-certified palliative care physician will be most qualified to assume facilitation of the family conference in the challenging ICU environment. The length of the family conference can vary due to the number of family members present (in person or on the telephone), complexity of the medical and family situation, time needed to express emotions, need to gather additional information from medical specialists, and the ability to reach a consensus within the family with the health care team. The facilitator can quickly identify and address any conflict within the family that will militate against a wise and thoughtful decision being made. Keeping the focus on what is best for the patient almost always supersedes ongoing unresolved family problems. Although many communication resources and guides are available, one of the most practical ways to facilitate communication about emotionally charged content has been described by Kirk et al and includes playing it straight, staying the course, giving time, showing you care, making it clear, and pacing information.35 Ultimately, there are no formulas that meet the needs of all families. The facilitator tries to orchestrate the information and recommendations provided by the attending physician and the attending in the ICU (who is charged with the ongoing management of the patient and family while in the ICU) with the family’s emotional needs and cognitive processes to maximize a sense of control, predictability, connection, and meaning. Within this context, the patient receives the most appropriate care, while the family is much more likely to be able to maximize active coping and minimize their regrets to the inevitable loss of a loved one.

Finally, the information and processes experienced by the family in the family conference can be used to make adjustments to goals of care as the situation changes. The facilitator can also play a supportive role by maintaining communication with the family and health care team.

Summary

The complex and emotionally charged environment of the ICU is difficult for patients, families and health care staff. Quality care, safety, patient and staff satisfaction, and wise resource deployment are all undermined when the palliative care and psychosocial needs of patients and their families are not adequately addressed. Physicians, nurses and other staff, although highly skilled and specialized, seldom have the time, inclination or skills to effectively address the ongoing requirements of this complex population. Data derived from Stage IV cancer patients, those most likely to be admitted to an ICU, report a large number of distressing concerns that are primarily concerned with problems that are strongly related to palliative care and psychosocial services. While family members consistently request to be included in decision making they require the guidance and support of health care professionals to tolerate the distress related to making, what they perceive to be, life or death decisions. Based on the recommendations from the influential 1997 IOM report on end of life care in the United States,13 Nelsen et al have developed a bundle of measures that that can be used for performance feedback related to quality of palliative care in the ICU.34 Innovative tools like this (measuring patient preferences, communication, social work intervention, spiritual support, and assessment and treatment of pain) can be used to accelerate the pace of quality palliative care services in the ICU.

Families are complex systems that require time and expertise to engage. Some families adapt easier than others to the realties of the ICU. For physicians, nurses and others in the ICU who attempt to support families, managing the palliative care and psychosocial aspects of care can be extremely time consuming and frustrating. Palliative care services can assist both the treating physicians and intensivists in managing their caseloads and improving the quality of life for patients and their families and to the decrease distress of the ICU staff. By simultaneously providing state-of-the-art disease-directed care along with the compassionate expertise of the palliative care, patients and families receive the best that the health care system can offer.

The family conference is a systematic approach to align relevant information, organize the health care team and support emotional regulation and decision making in the family. Most of all, the family conference addresses what bereaved families report was missing in their ICU experience: an organized team that includes them in decision making in an environment of emotional support and ongoing and open communication.

Recent history has demonstrated that advances in the ICU will continue to accelerate and that patients will directly benefit from this care. The survival benefits to hematological patients admitted to the ICU are a clear example of this. However, regardless of the pace or creativity of future technological advances, patients, families and our colleagues will remain psychological and spiritual beings who require a sense of control, predictability, connection and meaning in order to feel that their lives have a reason for being. By including the whole-person perspective as an essential element in the ICU experience, there is the possibility of a new partnership with patients and their families, to replace the strained one that now exists, leading to advances in a true science of caring.

Demographics by stage groups.

| Demographics . | Stage 4, %* (n=110) . | Stages 1–3, %* (n=352) . |

|---|---|---|

| *Percentages are rounded to the nearest second decimal place; thus, the columns may not always equal 100%. | ||

| Gender | ||

| Male | 58.70 | 32.70 |

| Female | 41.30 | 67.30 |

| Race | ||

| White | 63.20 | 73.00 |

| Hispanic | 14.20 | 12.60 |

| Asian | 13.20 | 5.70 |

| African American | 5.70 | 3.10 |

| Native Hawaiian/Other Pacific Islander | 0.90 | 0.30 |

| Native American/Native Alaskan | 0.90 | 0.90 |

| Unknown | 0.90 | 0.60 |

| Other | 0.91 | 3.8 |

| Present Relationship | ||

| Married | 57.00 | 61.40 |

| Single | 22.40 | 10.40 |

| Divorced | 11.20 | 14.70 |

| Widowed | 7.50 | 8.00 |

| Living with a Partner | 1.90 | 5.50 |

| Age | ||

| Min | 21 | 20 |

| Max | 87 | 93 |

| Mean | 59.80 | 58.34 |

| Standard Deviation | 14.03 | 13.36 |

| Primary Diagnosis | ||

| Head and Neck | 25.50 | 7.10 |

| Lung | 21.80 | 9.00 |

| Gastrointestinal | 16.40 | 9.60 |

| Blood | 14.50 | 7.30 |

| Breast | 7.30 | 42.10 |

| Genito-urinary | 4.50 | 3.10 |

| Prostate/Testis | 4.50 | 10.20 |

| Gynecological | 2.70 | 7.90 |

| Skin | 2.70 | 1.40 |

| Soft tissue/Bone | 0.00 | 2.30 |

| Stage | ||

| 1 | 0.00 | 37.90 |

| 2 | 0.00 | 33.60 |

| 3 | 0.00 | 28.50 |

| 4 | 100 | 0.00 |

| Demographics . | Stage 4, %* (n=110) . | Stages 1–3, %* (n=352) . |

|---|---|---|

| *Percentages are rounded to the nearest second decimal place; thus, the columns may not always equal 100%. | ||

| Gender | ||

| Male | 58.70 | 32.70 |

| Female | 41.30 | 67.30 |

| Race | ||

| White | 63.20 | 73.00 |

| Hispanic | 14.20 | 12.60 |

| Asian | 13.20 | 5.70 |

| African American | 5.70 | 3.10 |

| Native Hawaiian/Other Pacific Islander | 0.90 | 0.30 |

| Native American/Native Alaskan | 0.90 | 0.90 |

| Unknown | 0.90 | 0.60 |

| Other | 0.91 | 3.8 |

| Present Relationship | ||

| Married | 57.00 | 61.40 |

| Single | 22.40 | 10.40 |

| Divorced | 11.20 | 14.70 |

| Widowed | 7.50 | 8.00 |

| Living with a Partner | 1.90 | 5.50 |

| Age | ||

| Min | 21 | 20 |

| Max | 87 | 93 |

| Mean | 59.80 | 58.34 |

| Standard Deviation | 14.03 | 13.36 |

| Primary Diagnosis | ||

| Head and Neck | 25.50 | 7.10 |

| Lung | 21.80 | 9.00 |

| Gastrointestinal | 16.40 | 9.60 |

| Blood | 14.50 | 7.30 |

| Breast | 7.30 | 42.10 |

| Genito-urinary | 4.50 | 3.10 |

| Prostate/Testis | 4.50 | 10.20 |

| Gynecological | 2.70 | 7.90 |

| Skin | 2.70 | 1.40 |

| Soft tissue/Bone | 0.00 | 2.30 |

| Stage | ||

| 1 | 0.00 | 37.90 |

| 2 | 0.00 | 33.60 |

| 3 | 0.00 | 28.50 |

| 4 | 100 | 0.00 |

Problem-related distress by stage groups.

| Problems* . | Stage 4, % ≥ 3 (n = 110) . | Stages 1–3, % ≥ 3 (n = 352) . | Difference score, % . | Stage 4, % yes (n = 110) . | Stages 1–3, % yes (n = 352) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| * sorted in descending order by % > 3. | |||||

| Fatigue (feeling tired) | 53.80 | 40.60 | 13.20 | 9.10 | 10.20 |

| Sleeping | 44.20 | 32.40 | 11.80 | 13.60 | 8.80 |

| Pain | 44.20 | 28.40 | 15.80 | 10.90 | 7.30 |

| Finances | 41 | 25.90 | 15.10 | 16.30 | 8.20 |

| Understanding my treatment options | 39 | 21.80 | 17.20 | 20.90 | 18.40 |

| Me being dependent on others | 35.80 | 27.10 | 8.70 | 2.70 | 4.80 |

| Controlling my fear and worry about the future | 33 | 24.90 | 8.10 | 9.10 | 7.30 |

| Finding community resources near where I live | 31.40 | 20.60 | 10.80 | 10 | 9 |

| Feeling down depressed or blue | 31.10 | 26.40 | 4.70 | 10 | 5.40 |

| Solving problems due to my illness | 29.70 | 16.70 | 13.00 | 7.30 | 5.90 |

| Being anxious or nervous person | 29.20 | 24.70 | 4.50 | 7.30 | 6.50 |

| Managing my emotions | 27.60 | 22.50 | 5.10 | 5.50 | 5.90 |

| Recent weight change | 26.90 | 12.50 | 14.40 | 5.50 | 4.20 |

| Questions and concerns about the end of life | 25.70 | 19.90 | 5.80 | 6.40 | 4.50 |

| Managing work, school, home life | 24.30 | 18.80 | 5.50 | 3.60 | 4.50 |

| Losing control of things that matter to me | 23.80 | 17.40 | 6.40 | 4.50 | 4 |

| Talking with health care team | 23.30 | 13.50 | 9.80 | 8.20 | 8.80 |

| My ability to cope | 21 | 13.20 | 7.80 | 2.70 | 2.50 |

| Sexual function | 20.40 | 15.40 | 5.00 | 2.90 | 4 |

| Transportation | 19.20 | 13.50 | 5.70 | 8.20 | 7.60 |

| Needing someone to help coordinate my medical care | 19 | 12.20 | 6.80 | 10 | 6.80 |

| Nausea and vomiting | 17.80 | 12.70 | 5.10 | 5.50 | 3.40 |

| Talking with doctor | 17.30 | 9.50 | 7.80 | 8.20 | 6.50 |

| Getting medicines | 17 | 10 | 7.00 | 6.40 | 4.20 |

| Thinking clearly | 17 | 16 | 1.00 | 1.80 | 2 |

| Writing down my choices about medical care for the medical team and my family if I ever become too ill to speak for myself | 13.50 | 11.20 | 2.30 | 7.30 | 6.20 |

| Having people nearby help me or needing more practical help at home | 12.40 | 12 | 0.40 | 2.70 | 3.70 |

| Someone else totally dependent on me for their care | 11.50 | 11.70 | −0.20 | 1.80 | 2 |

| Controlling my anger | 11.30 | 12.40 | −1.10 | 2.70 | 2.50 |

| Substance abuse | 11.20 | 4.60 | 6.60 | 1.80 | 2 |

| Ability to have children | 8.80 | 7.50 | 1.30 | 1.80 | 2.50 |

| Talking with family, children and friends | 8.40 | 8.50 | −0.10 | 1.80 | 4.20 |

| Spiritual concerns | 8.40 | 4.50 | 3.90 | 0.90 | 1.70 |

| Thoughts of ending my own life | 8.40 | 4.70 | 3.70 | 0.40 | 0.00 |

| Abandonment by family | 6.70 | 4.70 | 2.00 | 2.70 | 0.60 |

| Any other problems you would like to tell us about? | 6.50 | 5.20 | 1.30 | 4.20 | 2.80 |

| Problems* . | Stage 4, % ≥ 3 (n = 110) . | Stages 1–3, % ≥ 3 (n = 352) . | Difference score, % . | Stage 4, % yes (n = 110) . | Stages 1–3, % yes (n = 352) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| * sorted in descending order by % > 3. | |||||

| Fatigue (feeling tired) | 53.80 | 40.60 | 13.20 | 9.10 | 10.20 |

| Sleeping | 44.20 | 32.40 | 11.80 | 13.60 | 8.80 |

| Pain | 44.20 | 28.40 | 15.80 | 10.90 | 7.30 |

| Finances | 41 | 25.90 | 15.10 | 16.30 | 8.20 |

| Understanding my treatment options | 39 | 21.80 | 17.20 | 20.90 | 18.40 |

| Me being dependent on others | 35.80 | 27.10 | 8.70 | 2.70 | 4.80 |

| Controlling my fear and worry about the future | 33 | 24.90 | 8.10 | 9.10 | 7.30 |

| Finding community resources near where I live | 31.40 | 20.60 | 10.80 | 10 | 9 |

| Feeling down depressed or blue | 31.10 | 26.40 | 4.70 | 10 | 5.40 |

| Solving problems due to my illness | 29.70 | 16.70 | 13.00 | 7.30 | 5.90 |

| Being anxious or nervous person | 29.20 | 24.70 | 4.50 | 7.30 | 6.50 |

| Managing my emotions | 27.60 | 22.50 | 5.10 | 5.50 | 5.90 |

| Recent weight change | 26.90 | 12.50 | 14.40 | 5.50 | 4.20 |

| Questions and concerns about the end of life | 25.70 | 19.90 | 5.80 | 6.40 | 4.50 |

| Managing work, school, home life | 24.30 | 18.80 | 5.50 | 3.60 | 4.50 |

| Losing control of things that matter to me | 23.80 | 17.40 | 6.40 | 4.50 | 4 |

| Talking with health care team | 23.30 | 13.50 | 9.80 | 8.20 | 8.80 |

| My ability to cope | 21 | 13.20 | 7.80 | 2.70 | 2.50 |

| Sexual function | 20.40 | 15.40 | 5.00 | 2.90 | 4 |

| Transportation | 19.20 | 13.50 | 5.70 | 8.20 | 7.60 |

| Needing someone to help coordinate my medical care | 19 | 12.20 | 6.80 | 10 | 6.80 |

| Nausea and vomiting | 17.80 | 12.70 | 5.10 | 5.50 | 3.40 |

| Talking with doctor | 17.30 | 9.50 | 7.80 | 8.20 | 6.50 |

| Getting medicines | 17 | 10 | 7.00 | 6.40 | 4.20 |

| Thinking clearly | 17 | 16 | 1.00 | 1.80 | 2 |

| Writing down my choices about medical care for the medical team and my family if I ever become too ill to speak for myself | 13.50 | 11.20 | 2.30 | 7.30 | 6.20 |

| Having people nearby help me or needing more practical help at home | 12.40 | 12 | 0.40 | 2.70 | 3.70 |

| Someone else totally dependent on me for their care | 11.50 | 11.70 | −0.20 | 1.80 | 2 |

| Controlling my anger | 11.30 | 12.40 | −1.10 | 2.70 | 2.50 |

| Substance abuse | 11.20 | 4.60 | 6.60 | 1.80 | 2 |

| Ability to have children | 8.80 | 7.50 | 1.30 | 1.80 | 2.50 |

| Talking with family, children and friends | 8.40 | 8.50 | −0.10 | 1.80 | 4.20 |

| Spiritual concerns | 8.40 | 4.50 | 3.90 | 0.90 | 1.70 |

| Thoughts of ending my own life | 8.40 | 4.70 | 3.70 | 0.40 | 0.00 |

| Abandonment by family | 6.70 | 4.70 | 2.00 | 2.70 | 0.60 |

| Any other problems you would like to tell us about? | 6.50 | 5.20 | 1.30 | 4.20 | 2.80 |

Disclosures Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The author declares no competing financial interests. Off-label drug use: None disclosed.

References

Author notes

Sheri and Les Biller Patient and Family Resource Center, City of Hope, Duarte, CA