Abstract

Thrombocytopenia is a common finding in pregnancy. Establishing the diagnosis of immune thrombocytopenia (ITP) in a pregnant patient is similar to doing so in a nonpregnant patient, except that the evaluation must specifically rule out other disorders of pregnancy associated with low platelet counts that present different risks to the mother and fetus and may require alternate distinct therapy. Many of the same treatment modalities are used to manage the pregnant patient with ITP, but others have not been determined to be safe for the fetus, are limited to a particular gestational period, or side effects may be more problematic during pregnancy. The therapeutic objective differs from that in chronic ITP in the adult because many pregnant patients recover or improve spontaneously after delivery and therefore maintenance of a safe platelet count, rather than prolonged remission, is the goal. Thrombocytopenia may the limit choices of anesthesia, but does not guide mode of delivery, and the fetus is rarely severely affected at birth. Patients should be advised that a history of ITP or ITP in a previous pregnancy is not a contraindication to future pregnancies and that, with proper management and monitoring, positive outcomes can be expected in the majority of patients.

Scope of the problem

Thrombocytopenia is a very common finding in pregnancy, occurring in approximately 10% of women.1,2 Although most women maintain a normal platelet count throughout gestation, the normal range of platelet counts decreases, and it is not uncommon for the platelet count to decrease as pregnancy progresses. Most low platelet counts observed in the pregnant patient are due to normal physiologic changes,3 whereas some disorders associated with thrombocytopenia occur with higher frequency and some causes are exclusive to pregnancy.4 When considering the diagnosis of immune thrombocytopenia (ITP) in pregnancy, all potential causes of thrombocytopenia must be considered and ruled out in turn.

Differential diagnosis of thrombocytopenia during pregnancy

Gestational thrombocytopenia

“Incidental” or gestational thrombocytopenia is the most common cause of pregnancy-associated thrombocytopenia, accounting for 65%-80% of cases.1,4 Increased blood volume, an increase in platelet activation, and increased platelet clearance contribute to a “physiologic ” decrease in the platelet count.3 Platelet counts are slightly lower in women with twin compared with singleton pregnancies, possibly due to increased coagulation system activation in the placenta. These changes generally bring about only a mild decrease in the platelet count, typically approximately 10%.5 The mean platelet count in pregnant women at term was found to be 213 000/μL compared with 248 000/μL in age-matched controls.1,6 Gestational thrombocytopenia tends to occur late, usually during the third trimester,7 but it should be noted that thrombocytopenia that appears during the last weeks of pregnancy can be the harbinger of HELLP syndrome (hemolysis, elevated liver function tests, low platelets) or acute fatty liver.8 Platelet counts < 70 000-80 000/μL or occurring during the first or early in the second trimester suggest an etiology other than gestational thrombocytopenia and require further evaluation.9

Gestational thrombocytopenia is not associated with adverse outcomes to the mother or fetus, and if the infant is thrombocytopenic, other etiologies such as infection and neonatal alloimmune thrombocytopenia should be investigated.4 Thrombocytopenia in the mother generally resolves quickly after delivery, usually within days and always within weeks.

Disorders associated with thrombocytopenia in pregnancy

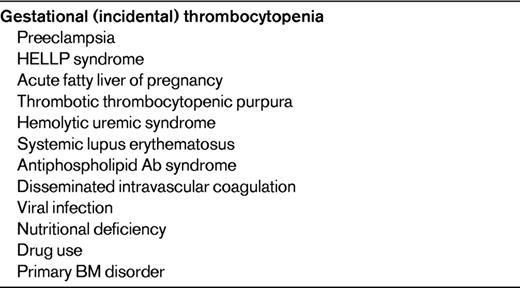

Many disorders are exacerbated by pregnancy or may be quiescent until the immunologic stimulation that occurs with pregnancy provokes their recrudescence (Table 1). Autoimmune disorders such as systemic lupus erythematosus may first appear or increase in severity during pregnancy, and hypothyroidism may first manifest during gestation. The antiphospholipid Ab syndrome, which is accompanied by thrombocytopenia in approximately 10%-30% of cases,10 must be considered because of its association with fetal loss and the need for anticoagulation.11

Thrombocytopenia first noted in the second or third trimester requires evaluation. Disorders that may first manifest at that time include preeclampsia, HELLP syndrome, acute fatty liver, disseminated intravascular coagulation, thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura, and hemolytic uremic syndrome. The abnormal clinical and laboratory findings that accompany these nutritional and BM disorders are the basis for distinguishing them from ITP. Careful review of the blood smear will help to exclude the thrombotic microangiopathies associated with pregnancy (ie, HELLP syndrome, thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura, and hemolytic uremic syndrome) by the absence of schistocytes. Normal coagulation studies will be helpful in excluding acute fatty liver and disseminated intravascular coagulation.

Thrombocytopenia may be the primary manifestation of viral infections such as HIV, viral hepatitis, EBV, and CMV. Thrombocytopenia is also a common adverse reaction from many drugs and supplements. Women who receive low-molecular-weight or unfractionated heparin are at risk of heparin-induced thrombocytopenia and should undergo testing, particularly in the presence of new or worsening thrombosis.

Evaluation of the pregnant patient with thrombocytopenia

The history and physical examination are important in providing clues to the diagnosis of thrombocytopenia in pregnancy, either by disclosure of preexisting thrombocytopenia or bleeding symptoms or by clinical findings of hypertension, edema, neurologic abnormalities, or signs of autoimmune disease. ITP diagnosed during pregnancy is usually relatively asymptomatic, and manifests in only mild symptoms and physical signs.12,13 Changes associated with a procoagulant state in pregnancy—increased levels of fibrinogen, factor VIII, and VWF; suppressed fibrinolysis; and decreased protein S activity—may explain in part why severe bleeding is only rarely seen in the pregnant patient with ITP.14 Although fatigue is a common symptom during pregnancy, other constitutional symptoms such a weight loss or drenching night sweats may signal etiologies of greater concern.

Medical history may be helpful in elucidating associated disorders such as thyroid disease or other autoimmune disorders. Frequent childhood infections may suggest an immune deficiency syndrome that can be associated with ITP.15 It is important to ascertain all drug and toxin exposures, including over-the-counter remedies and supplements. The nutritional history or a history suggestive of malabsorption may be helpful in the discovery of deficiencies that can manifest with thrombocytopenia. A family history of thrombocytopenia must also be investigated so that congenital thrombocytopenia is not mistaken for an acquired disorder.

Laboratory investigation of thrombocytopenia in pregnancy

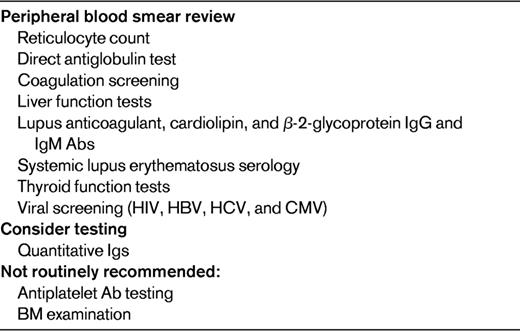

A complete blood count and review of the peripheral blood smear is mandatory in the evaluation of the thrombocytopenic patient (Table 2). Occasional large platelets may be seen in ITP, but they should otherwise appear normal. The presence of large and/or hypogranular platelets may suggest a congenital thrombocytopenia. Morphologic RBC abnormalities such as schistocytes, target cells, macrocytosis, or spherocytes may be clues to thrombotic microangiopathy, liver disease, nutritional deficiency, or autoimmune hemolysis. By definition, thrombocytopenia is an isolated hematologic abnormality in ITP, but anemia of pregnancy or anemia associated with chronic bleeding and iron deficiency may also be present. A direct antiglobulin test or Coombs test is necessary to rule out complicating autoimmune hemolysis (Evans syndrome). Screening for coagulation abnormalities (ie, with prothrombin time, activated partial thromboplastin time, and fibrinogen time), liver function (ie, tests for bilirubin, albumin, total protein, transferases, and alkaline phosphatase), antiphospholipid Abs, and lupus anticoagulant and serology may all be helpful in differentiating ITP from other disorders with associated low platelet counts. Viral screening (ie, for HIV, hepatitis C virus, and hepatitis B virus), as in the evaluation of nonpregnant patients with ITP,16 is recommended. A careful assessment of thyroid function is indicated because abnormalities are common in both ITP and pregnancy. Thyroid disorders are associated with significant pregnancy-related complications and with significant fetal risk, and the associated thrombocytopenia frequently responds to therapy. If the medical history suggests frequent infections, quantitative Ig testing may be appropriate. A review of preexisting laboratory data may reveal abnormalities that preceded the pregnancy or were present only during a prior pregnancy.

Recommended testing in the differential diagnosis of thrombocytopenia in pregnancy

HBV indicates hepatitis B virus; and HCV, hepatitis C virus.

Only rarely is BM examination necessary for the finding of thrombocytopenia in a pregnant patient, and it is not required to make the diagnosis of ITP. As in the nonpregnant patient, the measurement of antiplatelet Abs has no value in the routine diagnosis of ITP in pregnancy, is not predictive of neonatal thrombocytopenia, nor is it specific.17 Women with gestational thrombocytopenia cannot be distinguished from women with ITP based on detection of antiplatelet Abs, suggesting either that some cases thought to be “physiologic” gestational thrombocytopenia are actually due to immune destruction playing a role or may be an unmasking of previously compensated ITP.

Presentation of ITP during pregnancy

ITP occurs in approximately 2 of 1000 pregnant women.18 ITP may develop at any time during pregnancy, but is often initially recognized in the first trimester and is the most common cause of isolated thrombocytopenia in this time period. In some cases, ITP presents for the first time during pregnancy, whereas preexisting cases of ITP may either worsen or remain quiescent.19,20 A review of the clinical courses of 92 women with ITP during 119 pregnancies over an 11-year period found that women with previously diagnosed ITP were less likely to require therapy for ITP than those with newly diagnosed ITP,11 but the course varies widely.

Okay, I think it's ITP: now what?

Management of ITP during gestation

ITP in the first and second trimesters is generally treated when the patient is symptomatic with bleeding, platelet counts are in the 20-30 000/μL range, or a planned procedure requires a higher platelet count. In a retrospective analysis of 119 pregnancies in ITP patients, Webert et al found that only 89% of patients had platelet counts < 150 000/μL.11 Most patients had only mild to moderate thrombocytopenia and the pregnancies were uneventful, but 31% required intervention to increase the platelet count. Despite remaining relatively stable through most of the pregnancy, platelet counts may decrease during the third trimester and monitoring should be more frequent.15 Therapy late in gestation is generally based on the risk of maternal hemorrhage at delivery.

First-line therapy for ITP in pregnancy is similar to the management of acute ITP: corticosteroids21 and IV Igs.22 A combination of the 216 may be effective when a patient does not respond to a single agent alone. There are no comparative trials of the 2 agents, but responses appear to be similar to that in nonpregnant patients. Oral prednisone or prednisolone may be started at a low dose (10-20 mg/d) and adjusted to maintain a safe platelet count. Prednisone is generally safe in pregnancy, but it can increase weight gain and exacerbate hypertension and hyperglycemia, resulting in adverse effects on pregnancy outcome.23 Very high doses of corticosteroids are not harmful to the fetus and may have an effect of accelerating lung maturation, but antenatal corticosteroids have not been found to have an effect on the neonatal platelet count24 and should not be administered to the near-term mother with this objective. The emotional effect of corticosteroids or their rapid withdrawal in the postpartum period should be carefully monitored and dosage should be tapered to avoid a rapid decrease in the platelet count after delivery. IV Igs can be used for a rapid increase in platelet count or to maintain safe platelet counts when patients are not responsive to steroids or there are poorly tolerated side effects. Anti-RhD Ig is generally not used as a first-line agent because of concerns for acute hemolysis and anemia, but has been used in refractory cases throughout pregnancy with successful outcomes.25 If anti-RhD (50-75 μg/kg) is administered, the neonate should be carefully monitored for a positive direct antiglobulin test, anemia, and jaundice because the Ab may cross the placenta.

When a patient is only partially responsive or refractory to first-line therapy, azathioprine may be effective and has been safely administered during pregnancy.26,27 High-dose methylprednisolone may also be used in combination with IV Igs or azathioprine for the patient who is refractory to oral corticosteroids or IV Igs alone or has a less than adequate response.

Many agents that are frequently used in nonpregnant ITP patients, such as vinca alkaloids and cyclophosphamide, cannot be used in pregnant patients because of known or concern for teratogenicity. Cyclosporine A has not been associated with significant toxicity to the mother or fetus during pregnancy when used for inflammatory bowel disease,28 but there is no published experience on its use in ITP in pregnancy.

Although there are case reports of treatment of lymphoproliferative disorders with rituximab early in pregnancy,29,30 experience is limited and its use for pregnancy-associated ITP cannot be recommended because of its potential for crossing the placenta. Short-term therapy with danazol in combination with high-dose IV Igs and corticosteroids has been used for refractory thrombocytopenia in the third trimester,31 but longer-term use is likely to be teratogenic and should be avoided. There are no data on the use of thrombopoietin receptor agonists in pregnancy, and their effects on the fetus are unknown.

Splenectomy can be safely performed during the second trimester,32,33 when risks of anesthesia to the fetus are minimal and uterine size will not complicate the procedure. This approach may be useful for patients who remain refractory to therapy or who incur significant toxicity, and may even induce a remission.

Management of delivery

ITP in the mother is not an indication for Caesarean section,34 and the mode of delivery in a pregnant patient with ITP is based on obstetric indications. Most neonatal hemorrhage occurs at 24-48 hours35,36 and is not related to trauma at the time of delivery. Determination of the fetal platelet count by periumbilical blood sampling37 or fetal scalp vein blood draws present a potential hemorrhagic risk to the fetus and may inaccurately predict a low platelet count.16 For this reason, fetal platelet count measurement is not recommended. The best predictor of thrombocytopenia at birth is its occurrence in an older sibling. In this case, Caesarean section may be more prudent than vaginal delivery.

Maternal anesthesia must be based on safety of the mother. The risk of spinal hematoma at lower platelet counts is unknown, but recent recommendations are to withhold spinal anesthesia for women with platelet counts below 75 000/μL.38–40 Thromboelastograms have been suggested to evaluate the entire hemostatic state of the mother,41 but their usefulness is unclear. The bleeding time has also been suggested as a mode of establishing the safety of the platelet count,42 but most centers no longer offer this test and the experience in using it to predict bleeding at delivery is limited. For patients who have not required therapy during gestation but have platelet counts below the threshold required for epidural anesthesia, short-term corticosteroids (1-2 weeks) or IV Igs may help in preparing for the procedure. Platelet transfusion is not appropriate to prepare the mother for spinal anesthesia because posttransfusion increments may be inadequate or short-lived and should be reserved to treat bleeding only.

Monitoring and management of the neonate

Neonatal ITP accounts for only 3% of all cases of thrombocytopenia at delivery.43 There are no accurate predictors of fetal platelet count and the correlation between maternal and fetal platelet counts is poor.1,44,45 A recent retrospective study of 127 pregnancies in 88 women with ITP in Japan showed a trend toward lower platelet counts in the offspring of mothers with less than 100 000 platelets, but this was not statistically significant.46 Splenectomized mothers were also found to have a greater risk. Platelet count at birth appears to be related to the presence of alloantibody (in neonatal alloimmune thrombocytopenia), but not autoantibody, so platelet Ab testing is not recommended. A history of thrombocytopenia in a previous affected sibling appears to be the best predictor of thrombocytopenia in the neonate.45,47 Severe thrombocytopenia in the neonate delivered to a mother with ITP is relatively uncommon, with platelet counts < 50 000/μL occurring in 4.9%-25%.34,35,48,49 Mortality is rare (< 1%) and estimates of the incidence of intracranial hemorrhage in the neonate range from 0%-1.5%. At delivery, a cord blood platelet count should be obtained to determine the need for immediate therapy. Intramuscular injections such as vitamin K should be avoided unless it has been determined that the neonate has a safe platelet count. The nadir platelet count frequently occurs 2-5 days after birth, so the mother needs to be made aware of signs of bleeding and the baby should be checked early on by a pediatrician if he/she has been discharged to home. The thrombocytopenia can last weeks to months.50 A platelet count < 50 000/μL may be treated with IV Ig (1 g/kg), which can be repeated every few weeks as necessary to maintain a safe platelet count until the count spontaneously recovers.

Conclusion

ITP occurs fairly commonly in otherwise uncomplicated, normal pregnancies, but must be distinguished from more commonly occurring incidental gestational thrombocytopenia. Other disorders that may be associated with thrombocytopenia must be considered and ruled out so that appropriate therapy can be instituted. The diagnosis and management of ITP in pregnancy is similar to that in the nonpregnant adult patient, but the risks to the developing fetus must be taken into account when choosing treatment and the maintenance of a safe platelet count, rather than prolonged remission, is the goal. Mode of delivery must be guided by obstetrical indications. A history of ITP or ITP in a previous pregnancy is not a contraindication to pregnancy, and the majority of patients deliver nonthrombocytopenic or only mildly thrombocytopenic infants.

Disclosures

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The author has received research funding from Shionogi; has consulted for Glaxo-SmithKline, Clinical Options, Symphogen, Amgen, and Cangene; and has received honoraria from Hemedicus, Laboratorios Raffo, and Amgen. Off-label drug use: rituximab and azathioprine for ITP in pregnancy.

Correspondence

Terry B. Gernsheimer, MD, Box 357710, University of Washington, Seattle, WA 98195; Phone: 206-292-6521; Fax: 206-233-3331; e-mail: bldbuddy@u.washington.edu.