Abstract

Over the past 15 years, the use of reduced-intensity/nonmyeloablative conditioning regimens before allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation has been increasing. Despite major disparities in the level of myeloablation, intensity of immunosuppression (including great diversity of in vivo T-cell depletion), and postgraft immunomodulation, the different approaches have contributed jointly to a modification of the stage of allogeneic stem cell transplantation: transplantation-related procedure mortality has been decreased dramatically, allowing allogeneic immunotherapy to be used in previously excluded populations, including elderly patients, young but clinically unsuitable patients, patients with lymphoid malignancies or solid tumors, and patients without an HLA-identical related or unrelated donor. Together, these diverse regimens have provided one of the biggest breakthroughs since the birth of allogeneic BM transplantation. However, consensus on how to reach the optimal goal of minimal transplantation-related mortality with maximum graft-versus-tumor effect is far from being reached, and further studies are needed to define optimal conditioning and immunomodulatory regimens that can be integrated to reach this goal. These developments, which will most likely vary according to different clinical situations, have to be compared continuously with advances achieved in traditional allogeneic transplantation and nontransplantation treatments. However, the lack of prospective comparative trials is and will continue to make this task challenging.

“There is nothing new under the sun but there are lots of old things we don't know.”

Ambrose Bierce, The Devil's Dictionary

Introduction

Since the introduction of allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (allo-HSCT), the goal has always been to ensure engraftment, low toxicity, and high antitumor effects, but only recently has significant progress been made toward meeting this goal. This progress has only come from a tremendous effort over the years to improve our scientific knowledge and understanding of the inner mechanisms of allo-HSCT.

In 1965, Mathé used the term “adoptive immunotherapy” to define the mechanism of allo-HSCT as follows: “The theoretical principle of treatment of acute leukemia by adoptive immunotherapy is to permit allogenic, immunologically competent cells to act against the host's leukemic cells and the basic leukemogenic factors present in the host.”1 Nevertheless, from the time of the very first allo-HSCT using a matched sibling in a patient with blastic-phase chronic myeloid leukemia,2 it took nearly 20 years to confirm the existence of this principle in human allo-HSCT. The statistical evidence of the protective antileukemic effect of a GVH reaction required the accumulation of a large number of patients,3 and even then it was shown that, because of this correlation, the beneficial effect of a GVL effect was negated by increased incidence of GVHD-related mortality. Subsequently, the role of allogeneic donor T-cell lymphocytes was established through the increase in relapse when they were depleted from the graft4 or the ability to eradicate leukemia when added back after disease recurrence.5 Each of these successive steps demonstrated the close biological association between detrimental GVHD and needed GVL, and the many attempts since then that have tried to separate these immune reactions have consistently failed.

An important observation in the development of allo-HSCT has been that pretransplantation conditioning has important implications for the development of subsequent acute GVHD (a-GVHD). Indeed, in the early 1990s, Holler et al showed that GVHD was triggered by a proinflammatory cytokine release that was induced by conditioning-related cytotoxicity.6 This now classical cytokine cascade theory7 led to the suggestion that reducing cytokine generation might result in lower GVHD activation. This hypothesis was subsequently confirmed by the work of several teams who combined highly immunosuppressive agents with low cytotoxicity as the preparative regimen before allo-HSCT,8–10 distinguishing between and defining the so-called nonmyeloablative conditioning (NMAC) or reduced-intensity conditioning (RIC) regimens.11,12 However, the distinction between NMAC, RIC, and myeloablative conditioning (MAC) remains controversial. Moreover, more recent investigations of full myeloablation in the context of ensuring low toxicity in the so-called reduced-toxicity conditioning (RTC) regimens13 have added to the controversy regarding the definition of each conditioning transplantation term.

Historic MAC regimens

Conditioning regimens were originally intended to: (1) ensure allogeneic engraftment by providing profound immunosuppression of the host, making some “room” to allow for the graft to develop, and (2) to eradicate malignant disease. Initially, a high, single dose of total body irradiation (TBI) was used for this dual purpose based on a previous mouse model. However, because this caused frequent fatal tumor lysis in patients with active acute leukemia, cyclophosphamide (Cy) was added before the TBI in an attempt to prevent this severe tumor lysis. For years, the combination of Cy and high-dose TBI has achieved these 2 goals.14 However, because TBI was unavailable for several programs, the search for alternative antileukemic regimens started in the early 1980s. The highly myeloablative combination of oral busulfan (Bu) with Cy as an alternative for Cy + TBI developed into clinical practice with an apparent similar likelihood of engraftment and antileukemic effects.15 However, 4 randomized trials comparing TBI and a Bu-based conditioning regimen have been conducted predominantly in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia or acute myeloid leukemia (AML), and none of them have shown any statistical differences in overall or leukemia-free survival.16 A dose adjustment of Bu based on individual pharmacokinetics and the introduction of an IV formulation of Bu appeared to be promising, but no prospective trial including these advances has ever been tested against TBI. Attempts to intensify myeloablation either by increasing the TBI dose or by adding additional drugs for more advanced diseases, have been unsuccessful because the gain in disease control has been offset constantly by the increase in nonrelapse mortality (NRM).17–19 Although MACs represent 60% of the conditioning regimens used in Europe as of 2009,20 it is likely that the use of what can be called the “historic” conditioning regimens will continue to decrease based on the promising results of recent approaches.

RIC regimens

Non-MAC regimens were used initially to prepare patients with severe aplastic anemia for transplantation, and attempts to use them to treat malignancies were made only after a better understanding of allo-HSCT mechanisms had been achieved. However, this transition into the malignant setting represented a real challenge. The primary goal was to demonstrate a significant reduction in early transplantation related mortality. However, the high incidence of autologous hematopoietic recovery and mixed donor chimerism seen in severe aplastic anemia transplantations21 was a major concern, because mixed chimerism has been shown to be associated with a higher relapse rate in leukemia transplantations.22 Moreover, it was unknown at the time whether a GVL effect would be sufficient for achieving a curative antitumor effect without the help of antitumor conditioning. Fifteen years have now passed since the first reports of RIC regimens appeared. Although RIC regimens are used widely today (Figure 1), most of the medical and scientific information we have is from limited phase 2 studies, which are sometimes compared inappropriately with historical data, often in the form of registry data. Therefore, when it comes to the question of whether differences in conditioning regimens really matter, there is currently a lack of truly controlled comparative data, which makes it possible that significant patient selection bias may occur.

Trends in allo-HSCT in France over a 20-year period. Data are from the registry of the Societe Française de Greffe de Moelle et de Therapie Cellulaire.

Trends in allo-HSCT in France over a 20-year period. Data are from the registry of the Societe Française de Greffe de Moelle et de Therapie Cellulaire.

It is clear that successful engraftment is regularly achieved when sufficient immunosuppression has been given during conditioning and/or after transplantation.8 With this approach, full donor chimerism has been documented consistently, even if the pace of engraftment appears to be slower than the pace after classical MAC.20,23 Although a slow immune engraftment may have an impact on post-graft immune reactions, the detailed effect on acute GVHD incidence and severity and graft-versus-tumor (GVT) remains unclear.24 The reduction of early NRM with RIC that was shown in the early studies and confirmed in subsequent reports with widespread use of RIC20 (up to 2/3 of transplantation patients in France in 2010 receiving RIC; Figure 1) needs to be viewed in the context of a dramatic NRM decrease, which has also been documented after MAC.25,26 Several changes in transplantation practices over the years likely explain this observation: access to more sophisticated tools for monitoring patients and the disease itself, improved management of complications, and the availability of an increased number of effective anti-infectious drugs. In addition, shorter initial neutropenia related to the use of hematopoietic peripheral blood stem cells, better patient and donor selection, and data-driven use of standard operating procedures have also contributed to the improvement in NRM. Furthermore, the benefits of antitumor activity in RIC regimens have been documented in many situations, questioning the use of intensive chemotherapy in older patients27,28 and even the need for MAC allo-HSCT in younger patients.29 However, the absence of prospective comparative trials impairs the ability to draw definitive conclusions, with one of the major obstacles being dramatic changes in the characteristics of this population, because RIC patients today are often those for whom transplantations were not an option a decade ago.

AML still represents the major indication for allo-HSCT.20 A recent report reviewed several published trials regarding the role of NMAC/RIC allo-HSCT in adults with AML.30 Among them, the largest prospective phase 2 clinical study to date was published by the Seattle consortium, in which the role of NMAC conditioning with 2 Gy of TBI with or without fludarabine (Flu; 90 mg/m2 total dose) in 274 patients (median age, 60 years) with AML from related (n = 118) or unrelated (n = 156) donors who were not candidates for MAC regimens was evaluated.31 Cyclosporine A (CSA) and mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) were used for postgrafting immunosuppression. With a median follow-up of 38 months in surviving patients, the estimated overall survival (OS) at 5 years was 37%, 34%, and 18% for patients in first complete remission (CR1), CR2, and more advanced stages, respectively (P = .008), with an overall NRM of 26%. Interestingly, patients with HLA-matched related or unrelated donors had similar survival and relapse rates. The cumulative incidence of chronic GVHD (c-GVHD) at 5 years was 44%, and c-GVHD was associated with a lower relapse risk. Patients undergoing allo-HSCT within 6 months of diagnosis had a higher probability of posttransplantation relapse. This suggests that prior chemotherapy may affect posttransplantation outcome by effectively balancing the reduced strength of NMAC, which is in contrast to what was demonstrated several years ago in the MAC setting.32 In any case, this study confirmed that the use of NMAC before allo-HSCT could result in long-term remissions in AML patients for whom an allo-HSCT is otherwise contraindicated, which highlights the importance of the immune-mediated GVL effect in AML patients. This antitumoral effect has been confirmed with other NMAC associating antithymocyte-globulin (ATG) and total lymphoid irradiation.33,34 However, these promising findings lack a prospective comparison with chemotherapy alone. Therefore, we updated the report on the outcome of 95 AML patients who were diagnosed between 1999 and 2003 at a single institution, had achieved CR1, and were considered potential candidates for matched sibling RIC allo-SCT35,36 using a “genetic randomization” through a “donor ” (n = 35) versus “no donor ” (n = 60) comparison. In an “intention-to-treat ” analysis of the 95 patients entered in the study consecutively and with a median follow-up of 4.8 years (range, 3.5-7.2), the leukemia-free survival was significantly higher in the donor group compared with the no donor group (60 vs 23% at 7 years, respectively; P = .003), with low rates of relapse and NRM in the donor group. It is possible that these encouraging transplantation outcomes are due in part to the intensive consolidation chemotherapy given to all patients before RIC allo-HCT, which, once again, may highlight the significance of adequate disease control with intensive consolidation therapy before administration of a RIC allo-HCT. In conclusion, the worldwide experience with NMAC/RIC to date strongly suggests that this approach is a reasonable option for older patients and for younger patients with medical comorbidities for any AML after achieving a first or subsequent remission and needing an allo-HSCT. For patients with refractory or relapsed disease or who those use alternative donors, any allo-HSCT should be considered only within the context of clinical trials that compare results from MAC allo-HSCT treatment for younger patients or with controlled chemotherapy in older patients.

Because of the unique GVT effect of RIC/NMAC–based transplantations, other malignant diseases than leukemia, including solid tumors, have been considered for allo-HSCT. For many years, allo-HSCT has been ignored for these diseases due in part to prohibitive NRM observed after MAC. With less NRM from RIC/NMAC and a chemoresistant independent GVT effect, this scenario has changed progressively. Over the past few years, allo-HSCT has been investigated as a curative treatment in some of these nonleukemic malignancies.37–42 Although the results are promising and in some instances unprecedented, the use of RIC leaves many unanswered questions that require further investigation.

As discussed above, the ideal conditioning regimen before allo-HSCT has not yet been established. Continued clinical evaluations aimed at developing: (1) safer and more effective conditioning regimens, (2) novel methods to reduce the incidence and severity of GVHD without compromising the beneficial GVT effects, and (3) strategies to improve immune reconstitution after transplantation are needed before the goal of ultimately achieving durable long-term disease-free survival with good quality of life in patients with malignant diseases has been reached.

Despite the evidence of potent graft-versus-malignant disease effects, the optimal balance between myeloablation and immunosuppression in RIC before allo-HSCT remains undefined. Over the past decade, our program has addressed this important question in several consecutive studies. In one prospective randomized study, we compared 2 different popular conditioning regimen strategies including RIC and NMAC with the goal of identifying a regimen that could be improved upon.43 The RIC regimen (Flu-Bu-rATG) arm consisted of Flu (30 mg/m2/d for 5 days), oral busulfan (Bu; 4 mg/kg/d for 2 days), and rabbit ATG (rATG; (2.5 mg/kg on day 3). CSA alone was administered for postgraft immunosuppression. The second NMAC arm (Flu-TBI) included Flu (30 mg/m2/d for 3 days) and 2 Gy of TBI in 1 session on day 0. CSA and MMF were administered for postgraft immunosuppression. Each “regimen package” obviously differed from the other in terms of myeloablation (some with Bu vs no Bu combined with low-dose TBI) and immunosuppression (in vivo T-cell depletion in the Flu-Bu arm vs CSA and MMF in the Flu-TBI arm). A total of 139 patients with a median age of 55 years and with various hematologic malignancies received transplantations from a matched related donor and were randomized to receive NMAC or RIC. The incidence of grade II-IV acute GVHD was higher after Flu-Bu-rATG (47 vs 27%, respectively; P = .01), whereas the incidence of c-GVHD did not differ. The Flu-Bu-rATG cohort had a higher objective decrease in measurable diseases (65 vs 46%, respectively; P = .05) and lower relapse rates (27 vs 54%, respectively; p < .01). The NRM was higher after Flu-Bu-rATG than after Flu-TBI (38 vs 22%, respectively; P = .027). At 5 years, the OS was 41% for the entire cohort and did not differ statistically between the 2 groups, which overall can be considered favorable, considering the patient characteristics and long follow-up. Therefore, 5 years after transplantation, the Bu regimen was associated with better disease control than the Flu-TBI regimen; however, this did not translate into better OS, because the NRM rate in the Flu-BU group was higher. The conclusion from this trial was that both conditioning regimens had strengths and weaknesses, but were equivalent for OS. However, after this trial, we postulated that we could improve the results after Flu-BU-rATG treatment by decreasing NRM while concomitantly retaining superior antitumor activity by fine-tuning the dose of r-ATG, which is an option that remains controversial. First, we confirmed our results in a large, single-center cohort of 100 consecutive patients with hematological malignancies undergoing allo-HSCT from an HLA-matched related donor and treated with the same Flu-Bu-rATG RIC. With a median follow-up of 60 months, the probabilities of OS and progression-free survival at 5 years were 60% and 54%, respectively.43 NRM was adversely associated with acute GVHD (hazard ratio = 6; P = .0002), whereas the incidences of grade II-IV acute and extensive c-GVHD were 43% and 69%, respectively. These results led us to increase the dose of rATG to 5 mg/kg, because we postulated that this high rate of GVHD may be related to the low rATG dose, with the optimal dose being controversial in regard to GVHD prevention and disease control.45,46 A recent registry analysis from the Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research (CIBMTR) raised some concerns incautiously using in vivo anti–T-cell Abs as part of a RIC regimen.47 In this analysis, the median reported dose of rATG was 7 mg/kg, which represents a rather high dose. Indeed, we have shown previously that rATG doses of 7.5 and 10 mg/kg were associated with profound immunosuppression, which was responsible for sustained engraftment47 and a low rate of severe GVHD,48,49 but was a source of severe late infections50 and an eventual reduction of disease control.49 Data published by the Calgary group support that an intermediate dose around 4.5 mg/kg may be optimal in both preventing GVHD and retaining an antitumor effect.51 In support of these data, we recently reported that the dose of rATG had the same balance in patients with AML treated with MRD allo-HSCT after a RIC regimen that included a dose of 2.5 or 5 mg/kg of rATG.52 The higher rATG dose showed a dramatic reduction of the incidence and severity of a-GVHD and c-GVHD reduction without loss of GVT. Therefore, we believe that a RIC regimen consisting of Flu, IV Bu, and a moderate dose of rATG followed by postgraft CSA only represents a promising conditioning platform from which to further develop treatment strategies.

RIC has also been applied in the context of allo-HSCT using alternative donors, including cord blood and haplo-mismatched stem cell sources, and has shown promise in this area. However, the same questions remain regarding the overall impact that RIC has on HLA-matched related or unrelated transplantations. To answer these outstanding questions regarding conditioning regimen composition, stem cell source, and postgraft immunomodulation, extensive clinical research is currently being conducted in this area.

RTC regimens

With early NRM reduction after RIC/NMAC, disease control becomes the major issue with the observation that the relapse rate is higher than after MAC, although comparisons are difficult due to inherent differences in the different transplantation populations, which has been shown in a recent retrospective study.53 However, comparative attempts support that, compared with MAC, the OS rate after allo-HSCT with RIC/NMAC is similar, but for different reasons: a higher relapse rate and lower NRM after RIC/NMAC, and higher NRM and lower relapse rate after MAC.53–55 Recently, access to new cytotoxic drug formulations with more favorable toxicity profiles, such as IV Bu and treosulfan, may represent a significant improvement. Indeed, conditioning regimens containing these agents in combination with nucleoside analogs rather than additional alkylating agents or TBI has changed our conception of conditioning therapy and allowed for the systematic investigation of a new category of myeloablative regimens under the new designation of RTC regimens. Therefore, the RTC regimens contain drugs at myeloablative doses with a potent antileukemic effect, but with clinical toxicities similar to those of RIC/NMAC.

The replacement of oral Bu (osBu) with IV Bu is extremely important due to the well-known erratic bioavailability of the oral formulation and the narrow therapeutic index.56 As a consequence, IV Bu allows precise drug delivery and control of systemic exposure to minimize adverse effects and optimize the antitumor effect.56 The pharmacokinetic profile of IV Bu in combination with cyclophosphamide (IV BuCy2) administered in 4 daily doses for 4 days (total dose, 12.8 mg/kg) has been extensively evaluated.57–59 These studies have shown that the combination of IV Bu and Cy is easier to administer compared with osBuCy2 and is associated with a significant reduction of liver, CNS, and oral and pulmonary toxicities, with a low 1-year NRM of approximately 13%.58,60 In addition, a randomized study from South Korea confirmed that IV Bu administered once per day for 4 days (in 4 doses) had the same toxicity and efficacy profile compared with when it is administered 4 times a day for 4 days (ie, in 16 doses).61

In the standard combination of osBu plus Cy, liver toxicity is not only associated with osBu, but also with the combination of Bu with Cy.61 Furthermore, the antitumor activity of Cy in several hematological malignancies, such as AML, is questionable. Cy was originally added to a single high-TBI dose solely to mitigate an otherwise prohibitive tumor lysis in relapsed AL. Therefore, there are several reasons to suggest that Cy can be replaced with other, better tolerated immunosuppressive agents, such as a nucleoside analogs with high immunosuppressive and, in some cases, antileukemic effects. One such agent is Flu, which, with its alternative metabolism, would improve the clinical safety of the conditioning regimen.

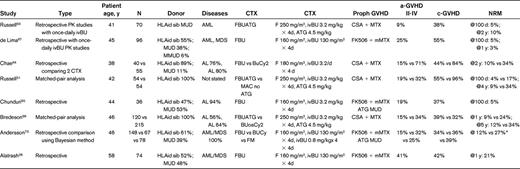

Table 1 lists studies that have used myeloablative IV Bu (12.8 mg/kg or 520 mg/m2) and Flu in combination. In the first study, 70 patients from Canada received IV Bu that was administered on a once a day schedule (3.2 mg/kg/d for 4 days) with Flu (50 mg/m2/d for 5 days) and rATG (4.5 mg/kg over 3 days) (FLUBUP).63 The GVHD prophylaxis consisted of CSA plus a short course of methotrexate treatment. HLA-matched identical donors were used for 43 patients and matched-unrelated donors were used for 21 patients. The mean 100-day and 2-year NRM was 2% and 10%, respectively, and the grade II-IV acute GVHD incidence was 8%. The incidence of grade II mucositis and hemorrhagic cystitis was 70% and 13%, respectively. The investigators did not observe clinical sinusoidal obstructive syndrome, and graft failure was observed in 2 (3%) of the patients. Russell et al compared 2 cohorts of patients: one conditioned with MAC without rATG and one receiving mostly FLUBUP with rATG (FLUBUP-T).51 The donors were HLA-identical siblings in both cohorts. The use of rATG reduced the NRM and c-GVHD rates significantly. The progression-free survival was similar between the 2 groups, but the OS was better in the cohort receiving rATG. However, the relapse rate was slightly higher in the rATG group, although this was not statistically significant. A third study from Calgary confirmed good tolerance of the FLUBUP-T when used before HLA-identical sibling transplantation. In that study of 200 patients with hematological diseases, the 5-year NRM was between 4% and 6% in patients with low-risk disease regardless of age, and 27% in patients older than 45 years with high-risk disease. The incidence of grade II-IV a-GVHD and c-GVHD was 14% and 54%, respectively.66 In a disease-specific study from the M.D. Anderson Cancer Center, 96 patients with AML or myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS; 56% with active disease at the time of transplantation) were grafted after a Bu-Flu variant conditioning regimen using Flu (40 mg/m2/d for 4 days) and IV Bu (130 mg/m2/d for 4 days).67 Tacrolimus and “micro-methotrexate” were used for GVHD prophylaxis, and low-dose rATG was added for patients having a one-antigen-mismatched related or unrelated donor. The tolerance of this regimen was promising: severe mucositis was observed in 13% and hemorrhagic cystitis in 3% of all patients. No neurotoxicity was observed, and only 2 patients developed reversible sinusoidal obstructive syndrome. Transaminase and bilirubin elevations were observed in 18% and 9% of patients, respectively. The majority of patients with active disease at the time of transplantation achieved CR, and the 1-year OS and disease-free survival for the entire group was 65% and 52%, respectively, with no differences between patients using HLA-identical donors or matched-unrelated donors.67,68

Studies using myeloablative IV busulfan (12.8 mg/kg or 520 mg/m2) and fludarabine

PK indicates pharmacokinetic; ivBU, intravenous busulfan; HLAid sib, HLA identical sibling; MUD, matched unrelated donor; MMUD, mis-matched unrelated donor; AL, acute leukemia; F, fludarabine; CTX, conditioning regimen; mMTX, micro-methotrexate; and FM, fludarabine plus melphalan.

*NRM for FM was not presented.

Combined, these studies confirmed good tolerance of myeloablative doses of IV Bu when used in combination with Flu, and demonstrated that NRM and a-GVHD/c-GVHD incidences were limited, in particular when rATG was added to the Bu-Flu variant regimens. Furthermore, the pharmacokinetic studies showed low inter- and intrapatient variability in Bu distribution.

Despite the favorable toxicity profile that may lead to better survival69 and the hypothesized synergistic antitumor effect of Bu and Flu,70 there remains some concerns as to whether the antitumor efficacy of FLUBUP-T is equivalent to the more standardized (primarily BuCy2) MAC regimens.69,71 Indeed, in a retrospective “matched-pair” analysis from the CIBMTR that compared FLUBUP-T and osBuCy2 before allo-HSCT in patients with hematological malignancies, the relapse incidence was higher (29 vs 12%, respectively) and the NRM was lower in the FLUBUP-T group (29 vs 12%, respectively) compared with the osBuCy2 group. However, the OS was similar in both arms. The investigators concluded that several factors may explain these somewhat paradoxical results, in particular the fact that the low NRM in the FLUBUP-T group allowed more patients to be exposed to a risk of relapse of their disease.69 Accordingly, Russell et al added a slightly higher dose of TBI (4 Gy) to the FLUBUP-T regimen and reported achieving a reduced relapse rate without increased toxicity.69 In a retrospective comparative study in AML/MDS patients, the Bu-Flu conditioning regimen was evaluated against IV BuCy2 using Bayesian methodology.73 In a cohort of mostly advanced patients (half of the patients were > CR1), the OS and event-free survival were significantly better in the Bu-Flu group compared with the IV BuCy2 (70 vs 59%, P = .03, and 62 vs 37%, P = .04, respectively). Similar results were observed in the subgroup of patients transplanted in CR. This study confirmed the efficacy of the Bu-Flu combination in advanced AML/MDS patients. There was no significant, detectable loss of antileukemic efficacy in the Bu-Flu group.73 A recent publication has provided new insights into this field. The MD Anderson team analyzed 79 patients who were 55 years of age or older (median, 58 years) with AML (n = 63) or MDS (n = 16) treated with IV Bu-Flu conditioning regimens between 2001 and 2009 (median follow-up, 24 months). The 1-year NRM rates for patients who were in CR or who had active disease at the time of transplantation were 19% and 20%, respectively. The 2-year OS rates for patients in CR1, CR2, refractory disease, and for all patients at the time of transplantation were 71%, 44%, 32%, and 46%, respectively. Moreover, the 2-year event-free survival rates for patients in CR1, CR2, or refractory disease at the time of transplantation and for all patients were 68%, 42%, 30%, and 44%, respectively.28 These results show that full-dose IV Bu can be safely administered to older patients.

These findings show that although a low toxicity profile is desirable, it must be associated with high disease control if one wants to have effective therapeutic results. The fine-tuning of new modalities offered by NMAC/RIC/RTC is the best approach to making this strategic pathway successful. However, to date, the absence of prospective trials confirming and prospectively comparing these data is a weakness that will need to be address in the future.

Conclusions

As described in this review, the lack of prospective randomized studies may suggest that none of the RIC/NMAC regimens “really makes a difference. ” NMAC regimens have a favorable safety profile, but their lack of ability to control malignant disease is a real issue, particularly for advanced or fast-growing malignancies. RIC can benefit from a limited degree of in vivo T-cell depletion, which results in a lower GVHD and NRM incidence, but this may impair disease control, which is a concern in more advanced diseases. Finally, the RTC regimen appears to provide better disease control with a reduced relapse incidence while concomitantly maintaining an adequate safety profile.

Regardless, the major contribution of all of these novel approaches has been the ability to offer allo-HSCT to a wider population, including patients diagnosed with diseases other than classical leukemia, patients above the classical age cutoff of 50 years, younger patients who are unfit for other treatments, and patients generally not considered for transplantation because of the increased risk of fatal complications. If we consider all of these advances, then it appears that the introduction of an RIC/NMAC/RTC strategy has made and will continue to make a difference, certainly over the past decade, and will likely to continue in the future. It is reasonable to envision that ongoing work in this area will define several new and ultimately optimal conditioning platforms before allo-HSCT, which will allow for the development of allogeneic immunotherapy strategies that include more sophisticated posttransplantation interventions.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Finn Bo Petersen, MD, Intermountain Healthcare SLC, for fruitful discussions and suggestions.

Disclosures

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: D.B. has received research funding from Pierre Fabre and Genzyme/Sanofi and has received honoraria from Pierre Fabre, Genzyme/Sanofi, and Otsuka. L.C. declares no competing financial interests. Off-label drug use: Busilvex is not presently registered for RIC in France.

Correspondence

Didier Blaise, Department of Hematology and Transplant and Cellular Therapy Program, Institut Paoli Calmettes, 232 Boulevard Sainte Marguerite, 13009 Marseille, France; Phone: +33-491-22-3754; Fax: +33-491-22-3443; e-mail: blaised@ipc.unicancer.fr.