Abstract

The treatment of multiple myeloma is evolving rapidly. A plethora of doublet, triplet, and quadruplet combinations have been studied for the treatment of newly diagnosed myeloma. Although randomized trials have been conducted comparing older regimens such as melphalan-prednisone with newer regimens containing drugs such as thalidomide, lenalidomide, or bortezomib, there are few if any randomized trials that have compared modern combinations with each other. Even in the few trials that have done so, definitive overall survival or patient-reported quality-of-life differences have not been demonstrated. Therefore, there is marked heterogeneity in how newly diagnosed patients with myeloma are treated around the world. The choice of initial therapy is often dictated by availability of drugs, age and comorbidities of the patient, and assessment of prognosis and disease aggressiveness. This chapter reviews the current data on the most commonly used and tested doublet, triplet, and quadruplet combinations for the treatment of newly diagnosed myeloma and provides guidance on choosing the optimal initial treatment regimen.

Introduction

Multiple myeloma is a plasma cell neoplasm that accounts for approximately 10% of all hematologic malignancies.1,2 Each year, more than 20 000 new cases are diagnosed in the United States.3 Almost all patients with myeloma have a preceding asymptomatic, premalignant stage termed monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS).4,5 The diagnosis of myeloma requires the presence of 10% or more clonal plasma cells on BM examination and/or a biopsy-proven plasmacytoma, as well as evidence of end-organ damage (ie, hypercalcemia, renal insufficiency, anemia, or bone lesions) that is attributable to the underlying plasma cell disorder.6

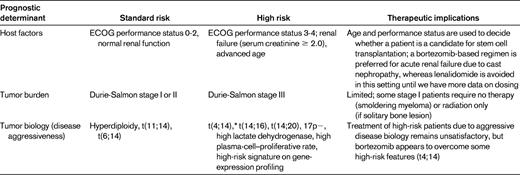

The treatment of myeloma is evolving rapidly. There are at least 5 active classes of treatment: alkylators (eg, melphalan and cyclophosphamide), corticosteroids (eg, prednisone and dexamethasone), proteasome inhibitors (eg, bortezomib and carfilzomib), immunomodulatory drugs (eg, thalidomide and lenalidomide), and anthracyclines (eg, doxorubicin and liposomal doxorubicin). Although thalidomide and lenalidomide are considered “immunomodulatory,” more recent studies show that the mechanism of action of these drugs may be mediated through cereblon, the putative primary teratogenic target for thalidomide.7,8 Numerous doublet, triplet, and quadruplet combinations have been tested using these drugs, and there is a striking paucity of randomized data that enable physicians to choose the best regimen for initial therapy. Most available randomized trial data are comparisons of newer regimens with older alkylator- or anthracycline-based regimens. The few trials that have compared more modern regimens with each other have relied on surrogate end points such as response rates or progression-free survival (PFS) rather than overall survival (OS) or patient-reported quality-of-life outcomes. Therefore, the prognosis of myeloma is dictated by numerous factors, all of which need to be considered when deciding on initial therapy (Table 1).9 As a result, until additional randomized data are available, the choice of initial therapy is often driven by opinion and consensus and requires a careful consideration of the risks and benefits. This chapter discusses the available data on initial therapy and provides an outline to help physicians choose an optimal treatment strategy for the newly diagnosed myeloma patient.

Prognostic factors in myeloma

*t(4;14) is considered “intermediate-risk” based on improved results seen now with bortezomib-based initial therapy.

Modified with permission from Rajkumar et al.9

Risk stratification

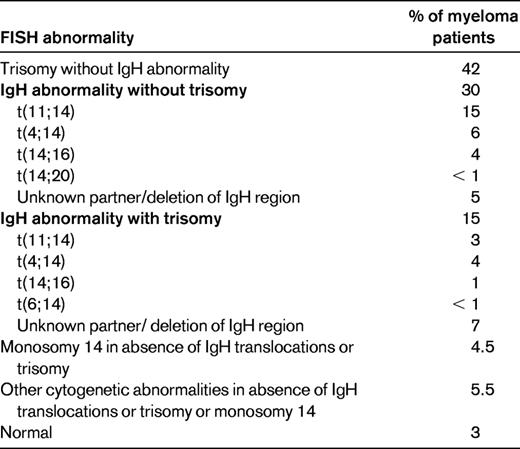

Myeloma is a cytogenetically heterogenous condition (Table 2).10 Most patients can be subdivided into at least 3 distinct primary cytogenetic categories defined by: (1) the presence of IgH translocations, (2) trisomies of odd-numbered chromosomes, or (3) both. These abnormalities originate at the MGUS stage, and are readily recognized on BM FISH studies. In addition to these primary cytogenetic abnormalities, which are thought to play a role in the pathogenesis of the MGUS stage, additional abnormalities occur during disease progression, including 17p deletion and secondary MYC translocations. At the Mayo Clinic, newly diagnosed myeloma is stratified into standard-, intermediate-, and high-risk disease using the Mayo Stratification for Myeloma and Risk-Adapted Therapy (mSMART) classification (see tumor biology section in Table 1).11 Patients with standard-risk myeloma have a median OS of 6-7 years, whereas those with high-risk disease have a median OS of less than 2-3 years despite tandem autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT).1 Appropriately treated patients with intermediate-risk disease can achieve survival similar to patients with standard-risk myeloma.12–15

Revised primary molecular cytogenetic classification of myeloma

Modified with permission from Kumar et al.10

Approach to initial therapy

Initial therapy for MM depends to a certain extent on eligibility for ASCT. Patients who are considered potential candidates for ASCT receive 2-4 cycles of a non-melphalan-containing regimen and then proceed to stem cell harvest.16 After stem cell harvest, most patients move on to ASCT (early ASCT). However, depending on response to initial therapy and patient preference, initial therapy can be resumed after stem cell harvest, delaying ASCT until first relapse (delayed ASCT). The pros and cons of early versus delayed ASCT have been debated extensively.17 In patients who are not candidates for ASCT, the duration of initial therapy is approximately 9-18 months for most regimens, although in the case of lenalidomide + low-dose dexamethasone (Rd), therapy is often continued until progression if the patient is tolerating treatment well.

Options for initial therapy

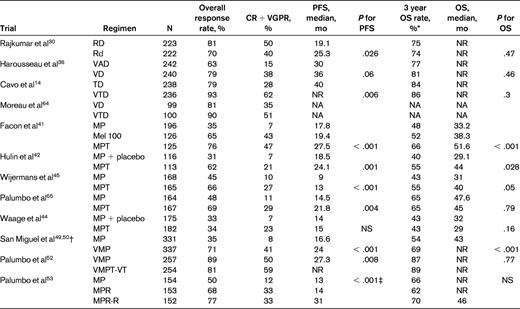

The specific regimen that can be used as initial therapy is affected by eligibility for ASCT, the prognostic variables listed on Table 1. Any of the regimens that are discussed are reasonable options for patients with newly diagnosed myeloma (Table 3). I have omitted regimens that have already been found to be inferior in terms of OS in recent randomized trials, such as melphalan + prednisone (MP); regimens that have become outdated in contemporary clinical practice for various reasons, such as vincristine + doxorubicin + dexamethasone (VAD); and regimens with limited data from randomized trials.

Results of recent randomized phase 3 studies in newly diagnosed myeloma

NA indicates not available; NS, not significant; and NR, not reached.

*Estimated from survival curves when not reported

†PFS not reported, numbers indicate time to progression.

‡For the comparison between MP and MPR-R and for the comparison between MPR and MPR-R; no significant difference between MP and MPR.

Modified with permission from Rajkumar.2

Doublet regimens

Thalidomide + dexamethasone (TD).

In newly diagnosed MM, TD produces response rates of 65%-75%.18–20 Two randomized trials found TD to be superior to dexamethasone alone, leading to the approval of the drug.21,22 However, TD is inferior in terms or activity and toxicity compared with lenalidomide-based regimens and is not recommended as the standard frontline therapy except in countries where lenalidomide is not available for initial therapy and in patients with acute renal failure, in whom it can be used effectively in combination with bortezomib. TD is not a good option for newly diagnosed patients over age 65; in one phase 3 study, the OS with TD was inferior to melphalan and prednisone.23 In a Mayo Clinic study of 411 newly diagnosed patients lenalidomide plus dexamethasone was significantly superior to TD in terms of response rate, PFS, and OS.24 Patients receiving thalidomide-based regimens require deep vein thrombosis (DVT) prophylaxis with aspirin, low-molecular weight heparin, or Coumadin.25–27

Rd.

Rd is active in newly diagnosed myeloma.28,29 In a randomized trial, Rd had less toxicity and better OS than lenalidomide plus high-dose dexamethasone.30 As a result, high-dose dexamethasone is no longer recommended in newly diagnosed myeloma. Further, the toxicity of high-dose dexamethasone makes it difficult to incorporate into triplet and quadruplet combination regimens. Rd is also an attractive option for the treatment of elderly patients with newly diagnosed myeloma because of its excellent tolerability, convenience, and efficacy. The 3-year OS rate with Rd in patients 70 and older who did not receive ASCT is 70%,31 and is comparable to results with melphalan + prednisone + thalidomide (MPT) and bortezomib + melphalan + prednisone (VMP). An ongoing phase 3 trial is currently comparing MPT versus Rd for 18 months versus Rd until progression. All patients receiving Rd require antithrombosis prophylaxis with aspirin; low-molecular-weight heparin or Coumadin is needed in patients at high risk of DVT.25–27 Rd may impair collection of peripheral blood stem cells for transplantation in some patients when mobilized with G-CSF alone.32 Therefore, in patients over the age of 65 and those who have received more than 4 cycles of Rd, stem cells must be mobilized with either cyclophosphamide + G-CSF or with plerixafor.33,34

Bortezomib + dexamethasone (VD).

Bortezomib, alone and in combination with dexamethasone, is active in newly diagnosed myeloma.35 Harousseau et al compared VD with VAD as pretransplantation induction therapy.36 Postinduction very good partial response (VGPR) was superior with VD compared with VAD: 38% versus 15%, respectively. This translated into superior VGPR after transplantation: 54% versus 37%, respectively. However, PFS improvement was modest, 36 versus 30 months, respectively, and did not reach statistical significance. No OS benefit is apparent so far.

Triplet regimens

Several 3-drug regimens such as bortezomib + cyclophosphamide + dexamethasone (VCD), bortezomib + thalidomide + dexamethasone (VTD), and bortezomib + lenalidomide + dexamethasone (VRD), are highly active in patients with newly diagnosed myeloma.37 These regimens can be used in all patients regardless of eligibility for ASCT. Conversely, melphalan-containing triplet regimens such as MPT, VMP, and melphalan + prednisone + lenalidomide (MPR) can only be used in patients who are not candidates for ASCT.

VTD.

VTD has been compared with TD in a randomized trial.14 VTD results in better response rates and PFS, but no OS benefit. Nevertheless, one of the most compelling findings in this study was the ability of VTD plus double ASCT followed by bortezomib-based consolidation to overcome the poor prognostic effects of t(4;14) translocation. In another randomized trial, VTD was found to produce better response rates and PFS compared with VD; no significant OS differences were reported.38 VTD is particularly useful in the setting of acute renal failure because it acts rapidly and can be used without dose modification.

VRD.

VRD produces remarkably high overall and complete response (CR) rates in newly diagnosed myeloma.37,39 A Southwest Oncology Group (SWOG) randomized trial has compared VRD with Rd in the United States, but no results from this study are available so far. An international phase 3 trial comparing VRD followed by early transplantation with VRD alone in newly diagnosed myeloma is ongoing. Although response rates and CR rates are very high with VRD, there are no data from randomized trials comparing the safety and efficacy of this rather expensive regimen compared with other less-expensive, equally effective, and possibly less toxic regimens. In myeloma, as in other cancers, it would therefore be premature to endorse expensive regimens such as VRD as standard therapy outside of a clinical trial to all patients. However, in the subset of patients with high-risk myeloma in whom all of the current options appear inadequate, it may be a reasonable treatment option to consider.

VCD.

VCD (also commonly known as CyBorD) has significant activity in newly diagnosed multiple myeloma,40 and is less expensive than either VTD or VRD. It represents a variation of the VMP regimen with substitution of cyclophosphamide for melphalan to improve tolerability. A randomized phase 2 trial in newly diagnosed myeloma (EVOLUTION) showed that VCD is well tolerated and has similar activity compared with VRD.39 CR was achieved in 22% and 47% of patients treated with 2 different schedules of VCD versus 24% of patients treated with VRD. Based on efficacy, ease of use, safety, and cost, VCD is an excellent choice when considering a bortezomib-containing regimen for frontline therapy.

MPT.

Six randomized studies have shown that MPT improves response rates compared with MP.41–46 A significant prolongation of PFS with MPT has been seen in 4 trials,41–43,45 and an OS advantage has been observed in 3 trials.41,42,45 Two meta-analyses of these randomized trials have been conducted and they show a clear superiority of MPT over MP.47,48 Grade 3-4 adverse events occur in approximately 55% of patients treated with MPT compared with 22% with MP.43 As with TD, there is a considerable (20%) risk of DVT with MPT in the absence of thromboprophylaxis.

VMP.

In a large phase 3 trial, VMP was associated with significantly improved OS compared with MP, which persisted with long-term follow-up.49,50 In a subsequent randomized trial, there was no significant advantage of bortezomib + thalidomide + prednisone (VTP) over VMP.51 Despite these results, VMP is not commonly used in the United States due to concerns about melphalan toxicity. Neuropathy is a significant risk with VMP therapy, but can be lowered substantially by using a once-weekly regimen.51,52

MPR.

MPR has been recently compared with MP in a randomized trial of patients 65 years of age or older with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma.53 The median PFS was similar between MPR and MP, 14 versus 13 months, respectively. A third arm that included lenalidomide maintenance showed a longer PFS, but is not relevant to the comparison of the efficacy of MPR versus MP. The disappointing lack of improvement in PFS with MPR compared with MP may be related to the fact that dose reductions of both melphalan and lenalidomide are often required when the 2 agents are combined. In addition, the incidence of second primary tumors in this trial was 7% with MPR compared with 3% for MP alone. An ECOG randomized trial (E1A06) has compared MPR with MPT and results are awaited.

Quadruplet regimens

Bortezomib + cyclophosphamide + lenalidomide + dexamethasone (VCRD).

Bortezomib + melphalan + prednisone + thalidomide (VMPT).

The quadruplet regimen of VMPT has been tested against VMP in a randomized phase 3 trial.52 The 3-year PFS rate was 56% with VMPT compared with 41% with VMP. However, patients in the VMPT arm received maintenance therapy with bortezomib and thalidomide, whereas patients in the VMP arm did not receive any additional therapy beyond 9 months. Further, no OS differences were seen: the 3-year OS was 89% with VMPT and 87% with VMP. Until OS differences emerge, there does not appear to be any advantage of using VMPT as initial therapy.

Multidrug combinations

In addition to the regimens discussed above, multiagent combination chemotherapy regimens such as bortezomib + dexamethasone + thalidomide + cisplatin + doxorubicin + cyclophosphamide + etoposide (VDT-PACE) have been tested extensively at the Myeloma Institute for Research and Therapy at Arkansas by Barlogie et al.12,55 VDT-PACE is particularly useful in patients with aggressive disease, such as plasma cell leukemia or multiple extramedullary plasmacytomas.

Choice of initial therapy

Numerous new doublet, triplet, quadruplet, and multidrug combinations are available for initial therapy in myeloma, but there are no randomized data with OS or patient-reported quality-of-life end points to aid in choosing between these modern treatment options. The choice of therapy is driven by other factors, including phase 2 data and randomized trials with surrogate end points such as CR or PFS. Although PFS is a useful end point for identifying active new agents, it is not a good surrogate for clinical benefit (OS or patient-reported quality-of-life) when trying to decide between 2 choices for initial therapy. In fact, in numerous instances, PFS has proven to be a poor indicator of clinical benefit, with the arm showing PFS advantage failing to show survival benefit35,38 or, worse, showing inferior OS.23 There is a vigorous “cure versus control” debate on whether we should treat myeloma with an aggressive multidrug strategy targeting CR or a sequential disease control approach.9,56 The discussion in the previous section “Options for Initial Therapy” and Table 3 provide a summary of available regimens that have undergone phase 3 testing. However, a mere listing of these options with a description of the response rates and PFS results will just represent a “laundry list ” of regimens. Figure 1 provides a suggested therapeutic approach that takes into account the available data on efficacy, toxicity, quality-of-life implications, anticipated prognosis, and cost of care. This approach is an evidence-based, risk-adapted strategy, and therefore relies primarily on data from randomized trials and uses risk stratification to decide on a particular regimen only when there are no clear survival data or quality-of-life data with which to choose between the various options.

Approach to the treatment of newly diagnosed myeloma in patients eligible for transplantation (A) and not eligible for transplantation (B). *For patients who choose delayed ASCT, dexamethasone usually discontinued after 12 months and continued long-term lenalidomide is an option for patients who are tolerating treatment well. Modified with permission from Rajkumar.2

Approach to the treatment of newly diagnosed myeloma in patients eligible for transplantation (A) and not eligible for transplantation (B). *For patients who choose delayed ASCT, dexamethasone usually discontinued after 12 months and continued long-term lenalidomide is an option for patients who are tolerating treatment well. Modified with permission from Rajkumar.2

Based on cost and toxicity considerations, Rd or a triplet regimen such as VCD are reasonable options for initial therapy in standard-risk patients. These doublet and triplet regimens have never been compared directly in randomized trials. The major advantage of VCD is the absence of increased risk of DVT, the lack of any adverse effect on stem cell mobilization, and higher CR rates. Drawbacks of VCD are the requirement for weekly visits to the clinic and the risk of neurotoxicity early in the disease course. However, recent studies show that the neurotoxicity of bortezomib can be greatly diminished by administering bortezomib on a once-weekly schedule51,52 and by administering the drug subcutaneously.57 There are no data showing that the more expensive VRD regimen is safer or more effective in terms of OS or quality-of-life compared with Rd or VCD (or VTD). Although in elderly patients, melphalan-containing triplet regimens such and VMP and MPT have proven efficacy over MP, it is not clear whether they would be superior to non-melphalan-containing regimens. In the United States, elderly patients can often receive ASCT and, as a result, melphalan-containing regimens are less often used as initial therapy.

In intermediate-risk patients, there are data from 3 randomized trials showing that bortezomib-containing regimens used in concert with double ASCT can almost fully overcome the poor prognostic effect conferred by the t(4;14) translocation.12–14 In total therapy 3, OS for patients with t(4;14) was identical to patients with hyperdiploidy or t(11;14), indicating that prolonged (1 year or longer) bortezomib-based therapy coupled with tandem ASCT can overcome completely the poor prognostic effects of this abnormality.13 Therefore, VCD or a similar bortezomib-containing regimen would be the preferred choice in this subset of patients.

In high-risk patients, even regimens such as total therapy 3, which contains VCD/VTD, double ASCT, and routine maintenance therapy, have failed to improve outcomes to levels achieved in standard- and intermediate-risk patients. Therefore, it is reasonable to consider VRD as initial therapy with a goal of achieving CR and sustaining it.

At present, the data are insufficient to recommend any quadruplet regimen as initial therapy outside of a clinical trial. There are special circumstances in which a multidrug regimen such as VDT-PACE may of value, such as in patients with extensive extramedullary disease or plasma cell leukemia at the time of initial diagnosis.12 In patients with acute renal failure due to suspected light-chain cast nephropathy, VCD (or VTD) is of particular value and is preferred as initial therapy.58

Once initial therapy is completed, there is an ongoing debate on continued maintenance therapy. Three recent randomized, placebo-controlled trials have investigated lenalidomide as maintenance therapy, but only 1 of the 3 trials has shown a survival benefit.53,59,60 A complete discussion of the pros and cons of maintenance is beyond the scope of this article. In short, data are insufficient to recommend routine maintenance with lenalidomide for all patients, but can be considered in subgroups of patients in whom the benefits appear to outweigh the risks (eg, standard-risk patients who are known to be lenalidomide responsive who are not in VGPR or better after completion of initial therapy). In intermediate- and high-risk myeloma patients, a bortezomib-based maintenance approach may be preferable and needs further study. In a recent trial comparing bortezomib + doxorubicin + dexamethasone (PAD) with VAD, patients randomized to the PAD arm received maintenance with bortezomib (every 2 weeks) after ASCT, and those in the VAD arm received thalidomide as maintenance.61 Preliminary results are encouraging and suggest improved PFS and OS with bortezomib maintenance, but it is not clear if this can be attributed to differences in induction or maintenance.

Emerging options

An emerging option for newly diagnosed myeloma that is promising is carfilzomib plus Rd.62 Carfilzomib is a novel keto-epoxide tetrapeptide proteasome that has shown single-agent activity in relapsed refractory multiple myeloma.63 Carfilzomib plus Rd will be compared with VRD in a planned ECOG trial in the United States in the near future.

Disclosures

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The author declares no competing financial interests. Off-label drug use: lenalidomide for newly diagnosed myeloma, carfilzomib for newly diagnosed and relapsed myeloma, and MLN 9708 for newly diagnosed and relapsed myeloma.

Correspondence

S. Vincent Rajkumar, MD, Professor of Medicine, Mayo Clinic College of Medicine, Division of Hematology, Mayo Clinic, 200 First St SW, Rochester, MN 55905; Phone: 507-284-2511; Fax: 507-266-4972; e-mail: rajkumar.vincent@mayo.edu.