Abstract

A 44-year-old otherwise healthy woman has completed 3 months of anticoagulation therapy for a first episode of unprovoked pulmonary embolism. At the time of diagnosis and before the initiation of anticoagulation, she was found to have an elevated IgG anticardiolipin antibody (ACLA), which was measured at 42 IgG phospholipid (GPL) units (reference range, < 15 GPL units) with negative lupus anticoagulant (LAC) testing. Should this laboratory finding affect the recommended duration of anticoagulant therapy?

The decision about whether to stop or continue anticoagulation after 3 months of therapy for a first episode of unprovoked venous thromboembolism (VTE) can be influenced by multiple factors, including the presence of risk factors for recurrent VTE, the presence or absence of bleeding risk and individual patient preferences, especially as they relate to the lifestyle implications of chronic anticoagulation. However, to justify the risk of major bleeding associated with anticoagulation, estimating the risk of recurrent VTE in the absence of anticoagulant therapy is critical. Several patient characteristics and clinical factors appear to increase the risk of recurrence, including male sex, signs and symptoms of postthrombotic syndrome, young age at diagnosis, elevated D-dimer at anticoagulant discontinuation, and obesity.1,2 Although the utility of testing for inherited or acquired thrombophilias (hypercoagulable states) in patients presenting with a first episode VTE is controversial, many experts recommend that patients with an antiphospholipid antibody (aPL), particularly those patients with antiphospholipid syndrome (APS), receive extended anticoagulation therapy because they are believed to have a higher risk of recurrence than other patients with a first unprovoked VTE.3,4

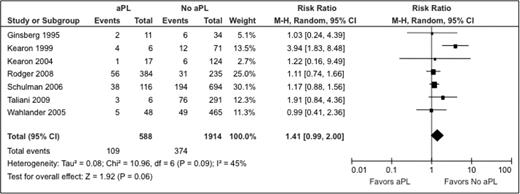

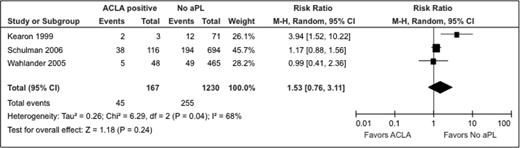

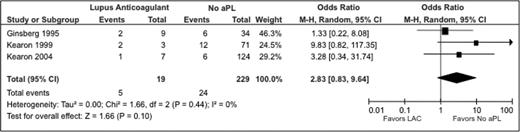

A recently published systematic review examined the question of whether laboratory evidence of an aPL (ACLA or LAC) is associated with an increased risk of recurrence among patients who have experienced a first episode of VTE.5 The pooled data from 7 included studies found 109 recurrent VTEs in 588 patients with aPL compared with 374 VTEs in 1914 patients without aPL (relative risk [RR] = 1.41, 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.99-2.36; Figure 1). Although the included studies defined positive aPL testing inconsistently, this meta-analysis suggests that there is an increase in risk of recurrent VTE associated with positive aPL testing. In patients with ACLA, the unadjusted RR was 1.53 (95% CI, 0.76-3.11) and for LAC, the unadjusted RR was 2.83 (95% CI, 0.83-9.64) (Figures 2, 3). However, the quality of the evidence was low and the estimate of the effect of a positive aPL test on the risk of recurrence was imprecise.

Relative risk for recurrent VTE in patients with an aPL compared with patients without an aPL.5

Relative risk for recurrent VTE in patients with an aPL compared with patients without an aPL.5

Relative risk for recurrent VTE in patients with an ACLA compared with patients without laboratory evidence of any aPL.5

Relative risk for recurrent VTE in patients with an ACLA compared with patients without laboratory evidence of any aPL.5

Relative risks for recurrent VTE in patients with an LAC compared with patients without laboratory evidence of any aPL.5

Relative risks for recurrent VTE in patients with an LAC compared with patients without laboratory evidence of any aPL.5

The last decade has seen advancements in the understanding of aPL and its association with thrombotic risk. Persistence of aPL, as documented by positive testing on more than one occasion (testing separated by a minimum of 12 weeks) and evidence of moderate-to-high titer antibodies (ACLA > 40 MPL or GPL units or exceeding the 99th percentile) meet criteria for “definite APS” and appear to have a stronger association with thrombosis and pregnancy complications.6-9 However, most studies that address this issue do not consistently identify individuals meeting such criteria. Indeed, the risk estimate for recurrent thrombosis in patients with definite APS as defined by the updated Sapporo criteria10 would almost certainly be higher than the RR associated with a single positive test. However, until such studies are performed, the magnitude of the risk increase cannot be known.

Until these studies are performed, clinicians must still assess whether positive aPL testing warrants extended anticoagulation. In making clinical decisions about secondary VTE prevention, clinicians should consider that laboratory evidence of aPL can be found in up to 8% of the general population,11 and that the circumstance underlying the index event (provoked vs unprovoked) is a powerful independent predictor of recurrence risk.12,13 Other considerations that may affect the duration of anticoagulation in a patient with an aPL might include whether the patient meets the updated Sapporo criteria for APS10 and whether the aPL is detected with more than one type of laboratory test.14 These features may identify a subset of aPL-positive individuals who have a particularly elevated risk of VTE recurrence.

In the above patient scenario, the patient had a single positive aPL test but did not meet the consensus criteria for definite APS. In such a scenario, we recommend repeat testing for aPL (including ACLA, LAC, and anti-beta-2-glycoprotein-1 antibodies) at least 12 weeks after the initial assay(s). Although there is little high-quality evidence establishing risk for recurrent thrombosis in patients with persistently abnormal aPL testing, we would recommend extended anticoagulation for such patients unless there were a compelling reason to withhold treatment (eg, a very high risk of anticoagulation-associated major bleeding). It is unclear whether thrombosis risk decreases in patients whose previously positive aPL testing becomes persistently negative.

If this patient's repeat aPL testing were negative, she would not meet the criteria for definite APS and the previously elevated ACLA measurement would need to be considered along with other clinical factors. The unprovoked nature of this patient's event predicts a substantial risk of recurrence irrespective of laboratory test results. Conversely, female sex is independently associated with a lower risk of recurrent VTE and her relatively young age would mean that “indefinite” or “lifelong” anticoagulation therapy could carry a significant cumulative bleeding risk. Switching to aspirin (ASA) therapy after 3 to 12 months of anticoagulation could be considered. However, ASA is less effective in preventing VTE compared with standard-intensity warfarin and a dedicated study of ASA for secondary VTE prevention in patients with an aPL has not been done. Newer, target-specific anticoagulants (ie, apixaban, dabigatran, and rivaroxaban) appear to be at least as safe and effective as warfarin for secondary VTE prevention. Although these agents have not been studied in patients with APS, they could be considered for a patient who is aPL negative but likely to benefit from extended anticoagulant therapy.

Ultimately, rather than recommending that all patients with an aPL receive indefinite anticoagulation, we suggest that clinicians interpret aPL testing in the context of an individual patient's risk factors, preferences, and laboratory values.

Disclosures

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: D.A.G. has consulted for Bristol Meyers Squibb, Pfizer, Janssen, and Boehringer Ingelheim. W.L. has received research funding from Leo Pharma, has consulted for Pfizer, and has received honoraria from Leo Pharma and Pfizer. Off-label drug use: None disclosed.

Correspondence

David A. Garcia, MD, Professor, Division of Hematology, University of Washington Medical Center, Box 357710, 1705 NE Pacific Street, Seattle, WA 98195-7710; Phone: 206-543-3360; Fax: 206-543-3560; e-mail: davidg99@u.washington.edu.