Abstract

There has been tremendous progress made in multiple myeloma in the last decade, resulting in improved overall survival for all patients, including those with high-risk disease and those ineligible for transplantation. However, despite the addition of several novel agents, unprecedented response rates, and our ability to achieve complete remission in the majority of patients, the disease remains incurable in nearly all and will require repeated therapies. With many options available to the clinician, there is no simple or ideal sequence of treatments that has been established, so the choice of relapsed therapy is based on a series of factors that include response and tolerability of prior therapies, risk status, available novel agents, aggressiveness of relapse, renal function, performance status, cost, etc. This chapter provides practical guidance in selecting relapsed therapies structured through a series of 5 questions that can inform the decision. Specific emphasis is placed on the 2 most recent novel agents, carfilzomib and pomalidomide, but agents in development are also included.

Learning Objective

To develop a systematic approach to the individualized selection of therapies for patients with relapsed multiple myeloma

Introduction

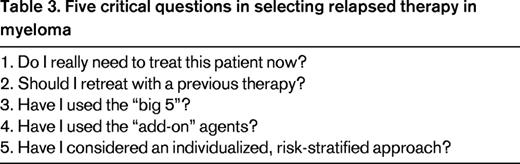

The management of multiple myeloma has undergone tremendous evolution over the last decade. There have been waves of interventions that have positively affected both the quantity and quality of life of patients. These have included the use of autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT) and the novel agents thalidomide, bortezomib, and lenalidomide.1 However, despite these great advances, the disease remains incurable.2 More recently, a host of new agents have been added to the options of therapy for relapsed myeloma, making treatment selection complex and emphasizing the need for an individualized approach. Indeed, several modalities of treatment are now available, including novel agents, traditional chemotherapy, combinations of both novel and traditional agents, rescue ASCT, and clinical trials. Balancing efficacy, toxicity, and cost will become ever more challenging with these increased options. This chapter focuses on that approach, seeking to provide a practical algorithm to guide the optimal treatment selection based on 5 critical questions that should be asked. Specific emphasis is given to the 2 most recently approved agents, carfilzomib and pomalidomide, because deciding between them is a common clinical conundrum. Emerging therapies are also discussed briefly because they will surely enhance treatment approaches in the future.

Defining relapsed myeloma

The terms “relapsed” and “refractory” are often used interchangeably and may be confusing. The International Myeloma Working Group clarified the definitions to facilitate uniform reporting.3 In general, “relapsed” refers to disease recurrence in the absence of current therapy after the patient has had an established response. This will require at least a 25% rise in the monoclonal protein in the serum (minimum 0.5 mg/dL) or urine (200 mg/24 hours) or the development of new plasmacytomas or hypercalcemia. As discussed in the next section, the sheer presence of biochemical relapse does not always indicate a need for systemic therapy. “Relapsed/refractory” refers to a relapse when a patient is currently on therapy (or within 60 days of completing treatment) after a previous response. It is preferable to specify refractory to a specific agent as opposed to refractory in general. This becomes very important when deciding on potentially reinstituting agents as to whether the patient was simply exposed to an agent or genuinely refractory. This also facilitates terms such as “dual refractory” to 2 agents (such as bortezomib and lenalidomide). Finally, the phrase “primary refractory” refers to patients who do not achieve a response to therapy. This may be the most difficult disease to control, although with increased options and the heterogeneity of myeloma, other agents may confer a desirable response.

Stepwise approach to relapsed myeloma

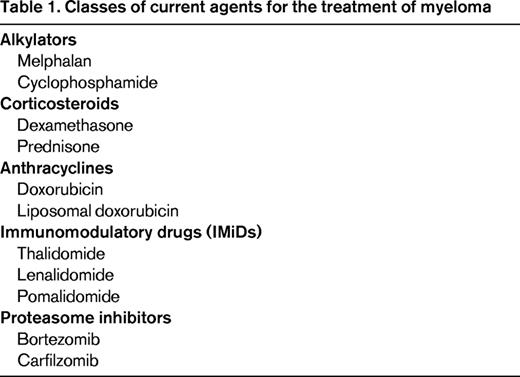

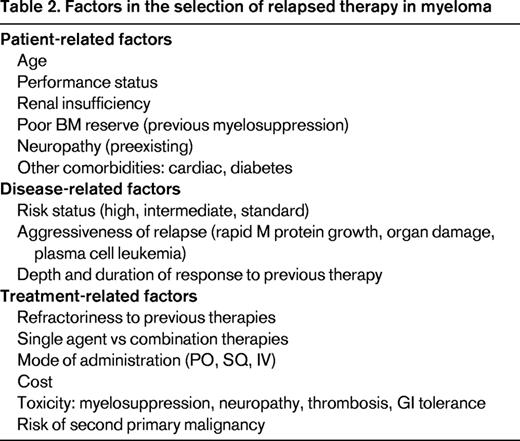

There are several treatments available for relapsed myeloma; the 2014 National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines identified nearly 20 options.4 There are now 5 classes of drugs used in myeloma (Table 1). Selecting the ideal therapy requires the consideration of several patient-related, disease-related, and treatment-related factors (Table 2). To ensure that each of these is addressed appropriately, the following 5 questions should be asked (Table 3).

1. Do I really need to treat this patient now?

Unlike many other malignancies, the sheer presence of disease does not always invoke immediate therapy in myeloma. It is an incredibly heterogenous disease that may be very indolent, with relapse occurring over months to even years, or it can be very aggressive, relapsing in a matter of days to weeks. This spectrum of disease is well appreciated in the untreated setting, with defined categories of MGUS (monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance) myeloma, smoldering (asymptomatic) myeloma, and overt multiple myeloma. The general trigger for therapy in this setting is the presence of end organ damage, defined by the acronym CRAB (elevated calcium, renal insufficiency, anemia, and bone disease).5 However, emerging evidence that other features, such as ≥60% marrow plasmacytosis and involved/uninvolved free light chains ≥100, may also define active disease due to imminent organ damage.6 In the relapsed setting, a more liberal trigger may be used because the patient has already met criteria for therapy previously; specific guidelines from the International Myeloma Workshop Consensus Panel have suggested that, at minimum, patients must have a doubling of the M component in 2 consecutive measurements separated by ≤2 months or an increase in the absolute levels of the M protein by ≥1 g/dL, involved free light chain ≥20 mg/dL (plus an abnormal FLC ratio), or urine M protein ≥500 mg/24 hours in 2 consecutive measurements in ≤2 months.3 Even in the absence of CRAB criteria, these guidelines should result in the introduction of relapsed therapy. However, if relapse is more indolent, without evidence of end organ damage, patients may be simply monitored (usually monthly) because they can often remain untreated for many months.

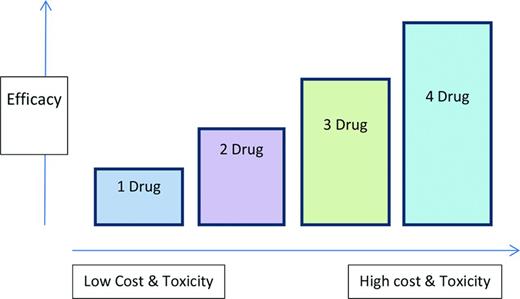

Identifying the “indolent” versus the “aggressive” relapse is crucial. In the indolent relapse, it is reasonable to introduce a sequential approach using 1-2 agents at a time, usually a proteasome inhibitor or an immunomodulatory drug (IMiD) plus a steroid, with the expectation of prolonged response, eventually using all active agents in myeloma. This is often termed the “control” approach and is more likely to be used in standard-risk myeloma.7 In contrast, a more aggressive relapse with a rapidly growing M spike, extensive end organ damage, dramatic cytopenias, or even plasma cell leukemia requires a more aggressive treatment regimen often with several agents used in combination and possibly more than one novel agent at a time. These options include combinations such as CyBorD (cyclophosphamide, bortezomib, dexamethasone), VRD (bortezomib, lenalidomide, dexamethasone), KRD (carfilzomib, lenalidomide, dexamethasone), PVD (pomalidomide, bortezomib, dexamethasone), KPD (carfilzomib, pomalidomide, dexamethasone), or traditional combinations such as DT-PACE (dexamethasone, thalidomide, cisplatin, adriamycin, cyclophosphamide, etoposide) or DCEP (dexamethasone, cyclophosphamide, etoposide, cisplatin). The rationale for combination therapy is 4-fold. First, myeloma is a heterogenous disease often with multiple clones8 and combinations may overcome several clones together. Second, combinations result in less resistance against a single pathway. Third, combinations maximize different mechanisms of action (ideally without overlapping toxicities). Finally, clinical experience has demonstrated that patients may respond to agents to which they were previously refractory when reexposed in combination. For example, when patients genuinely refractory to bortezomib and lenalidomide were treated with the combination of bortezomib plus lenalidomide (and dexamethasone), ∼30% responded.9,10 However, it is also important to consider the additional toxicity and cost of these regimens, which should therefore be reserved for patients with more aggressive disease. This theory is illustrated in Figure 1, which highlights the benefits of increasing efficacy but also increasing toxicity and cost of multiple agent use. Although the phenomenon of efficacy, toxicity, and cost are not linear as presented in the figure, they must be considered when adding more agents to a patient's regimen. The optimal balance of either extreme (too few vs too many agents) will depend on the factors described below.

2. Should I retreat with a previous therapy?

Because patients now live longer with myeloma, very often over a decade, a long-term approach to therapy is necessary. Although there are many options for relapsed myeloma, eventually nearly all patients will continue to relapse with disease that will become multidrug resistant. As a result, it is important to use all feasible therapies available, and this will often include retreating with agents that have been used before. Three critical factors will help to determine whether retreatment is feasible. The first is the depth of the initial response. The deeper the response (ie, at least partial remission, preferably even deeper), the more likely that there will be response again when the patient is reexposed to the agent. The second and perhaps most important factor is the duration of the first response. With each successive treatment in myeloma, the duration of response tends to diminish,11 so repeating a therapy is reasonable if there has been at least a 6 month duration of response. Third, the tolerability of an agent must be considered, especially for toxicities known to be prolific in myeloma, such as neuropathy, cytopenias, fatigue, and thrombosis. Although newer novel agents are more easily tolerated than historical chemotherapy, these factors must be considered when retreatment is initiated. Some of these may be overcome with dose reduction (especially thalidomide and lenalidomide), weekly dose adjustment (bortezomib),12 and route of administration (subcutaneous bortezomib).13 In contrast, consideration may be given in late stages of the disease to reusing an agent to which the patient was previously refractory; the rationale for this includes the theoretical demonstration of clonal evolution in myeloma8 that can result in clones that may now be drug sensitive. This has also been seen clinically in the example previously stated of successfully salvaging patients resistant to bortezomib and lenalidomide with bortezomib plus lenalidomide, along with dexamethasone.9

3. Have I used the “big 5”?

Five “novel” agents remain the center of myeloma therapy, comprising the 2 major classes of IMiD, including thalidomide, lenalidomide, and pomalidomide, along with the proteasome inhibitors bortezomib and carfilzomib. Although carfilzomib and pomalidomide are “newer-generation” agents, the original 3 agents remain a critical part of myeloma therapy and have not been replaced.

Thalidomide

Despite its tragic history >50 years ago, this agent has proven its efficacy in myeloma, with response rates of >25% in heavily pretreated disease,14 and has been effectively combined with cyclophosphamide, bortezomib, and, more recently, with carfilzomib. Although used less frequently in the United States, thalidomide remains a worldwide standard in myeloma due to its accessibility, minimal myelosuppression, and oral administration. These features make it an attractive partner in combination, especially when myelosuppression must be avoided. Important side effects include neuropathy, somnolence, thrombosis, and constipation.

Bortezomib

Bortezomib is a frequently used agent in myeloma, both in upfront and relapsed disease. The initial single-agent response rate in heavily pretreated patients was 27%,15 but this agent has been successfully combined with nearly every other myeloma therapy, most commonly with cyclophosphamide, thalidomide, lenalidomide, and melphalan. Its original dose and administration was 1.3 mg/m2 twice weekly intravenously, but it is now often given weekly 1.5 mg/m2,12 and subcutaneously.13 It may be used in all degrees of renal insufficiency, is rapidly acting, and may overcome certain high-risk features. The major toxicities of bortezomib include neuropathy, thrombocytopenia, and rash (when given subcutaneously).

Lenalidomide

Lenalidomide in combination with dexamethasone was compared with placebo and dexamethasone in 2 large phase 3 trials, both of which validated its activity in ∼60% of relapsed patients and showed a survival advantage.16,17 Lenalidomide has a convenient oral administration and has also been successfully combined with many other agents, including bortezomib and carfilzomib. Typical dosing is 25 mg daily for 21/28 days, although this may be adjusted to 5-15 mg. Its main toxicities include myelosuppression, fatigue, thrombosis, chronic diarrhea, muscle cramps, and possibly increased second primary malignancies.

Carfilzomib

Carfilzomib is a selective and irreversible proteasome inhibitor that was Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved in July 2012 for myeloma patients who are refractory to their last therapy with previous exposure to bortezomib and an IMiD (thalidomide or lenalidomide). It has demonstrated consistent single-agent activity, even in patients previously treated with bortezomib.18,19 It is given intravenously twice weekly for 3 weeks of 4. The dose is generally reduced in cycle 1 due to the risk of tumor lysis. Carfizomib has been successfully combined with lenalidomide, with response rates exceeding 60% and prolonged responses. It is generally well tolerated, but is associated with myelosuppression, fatigue, diarrhea, and possible cardiac effects. The cardiotoxicity was partially accounted for by increased hydration provided due to the risk of tumor lysis, but patients with preexisting heart failure or poorly controlled hypertension should be monitored more closely with careful fluid assessment. Neuropathy is very infrequent, making carfilzomib very attractive in patients with current or anticipated neuropathy. It can also be used in all degrees of renal insufficiency. Initial studies are investigating the potential of its use in weekly administration. It has also been successfully combined with lenalidomide in relapsed disease,20,21 with anticipated results of a phase 3 trial of carfilzomib-lenalidomide-dexamethasone versus lenalidomide-dexamethasone expected soon.

Pomalidomide

Pomalidomide is the most recent IMiD agent to be FDA approved for relapsed myeloma in patients with previous use of bortezomib and lenalidomide. It has similar properties to thalidomide and lenalidomide, but has proven efficacy in heavily pretreated myeloma, even in patients refractory to lenalidomide.22,23 The pivotal trial of pomalidomide alone versus pomalidomide-dexamethasone demonstrated a 33% response rate.24 Patients with high-risk myeloma did not appear to have an inferior outcome. Pomalidomide is orally administered and is well tolerated, with side effects of myelosuppression, thrombosis (mandating thromboprophylaxis), rash, and constipation. Typical dosing is 4 mg daily for 21/28 days, although the 2 mg dose has similar efficacy and may be considered when used in combination or when myelosuppression is a concern. Neuropathy is rarely seen, although worsening of preexisting neuropathy has been reported. It has been successfully combined with bortezomib, cyclophosphamide, and, most recently, with carfilzomib. Pomalidomide can be used in patients with mild to moderate renal insufficiency, but has not been tested in patients with serum creatinine ≥3 mg/dL.

Carfilzomib, pomalidomide, or both?

With very similar FDA indications for relapsed myeloma, deciding between these 2 agents is a common clinical problem. It should be reassuring to the clinician that each myeloma patient will likely ultimately see both agents and the optimal sequence is not yet known. Factors that may favor one option over the other include renal insufficiency with creatinine ≥3 mg/dL (carfilzomib), convenience of administration (pomalidomide), preexisting neuropathy (carfilzomib), and poorly controlled heart failure/hypertension (pomalidomide). A common clinical problem is treating a patient with “dual refractory” disease; that is, a patient who is refractory to both lenalidomide and bortezomib. Some prefer to “class switch,” selecting a proteasome inhibitor if the most recent therapy was an IMiD (and vice versa). Although this is a theoretical advantage, each agent has efficacy in the same class of refractory disease and may be used. The degree of “refractoriness” may also guide one to class switch if the patient has had limited or short-lived response to one class, but this has not been formally validated. Both agents have been demonstrated early efficacy in high-risk disease (eg, the p53 deletion) and so may be used in that context.

There is also emerging evidence for use of the combination of carfilzomib and pomalidomide. This may be considered in patients with a very aggressive relapse in whom both an IMiD and proteasome inhibitor is desired.25 Furthermore, when a patient is relapsing on one of these agents, the addition of the other may confer benefit, especially if limited other options exist.

4. Have I used the “add-on” agents?

Although the 5 key agents are considered the “backbone” of therapy for myeloma, several other agents have activity that can enhance their efficacy.

Corticosteroids

The most commonly used “add-on” agent is a corticosteroid, usually as weekly dexamethasone (20-40 mg) or alternate day prednisone (25-100 mg). High-dose dexamethasone is no longer routinely used due to its toxicity, but may be considered for short periods to enhance response during aggressive relapse. Dexamethasone is routinely used in combination with IMiDs and in the majority of patients receiving a proteasome inhibitor.

Alkylating agents

Cyclophosphamide is an alkylating agent that has less stem cell toxicity than melphalan and has been frequently combined with nearly all novel therapies with success, most commonly with bortezomib in the CyBorD regimen.12 When given orally and weekly (usually 300 mg/m2, but dose reduced in the elderly or in those with renal dysfunction), it is very well tolerated.26 It may also be used intravenously when more aggressive therapy is desired. Melphalan remains the standard of care as conditioning for ASCT and is often used orally in elderly patients with newly diagnosed myeloma. However, with the increased use of novel agents in the frontline setting, many patients at relapse have not been treated with melphalan. It may be used in combination with steroids or novel agents orally and as monotherapy intravenously.27

Liposomal doxorubicin

When combined with bortezomib in a phase 3 trial, liposomal doxorubicin prolonged time to progression by 2.8 months and improved overall survival compared with bortezomib alone and is therefore approved in relapsed myeloma.28 It may also be combined with lenalidomide.29

Some patients may benefit from combinations that do not include novel agents, such as oral or intravenous cyclophosphamide, oral or intravenous melphalan, or liposomal doxorubicin; each of these can be combined with steroids (prednisone or dexamethasone).

5. Have I considered an individualized, risk-stratified approach?

Risk stratification

Multiple myeloma is a biologically and clinically heterogenous disease, with some patients only surviving 1-2 years and others >20 years. It is well recognized that a minority of patients have genuinely high-risk disease, which is usually associated with the p53 deletion, t(14;16), t(4;14), high-risk gene expression profiling, or clinical features such as plasma cell leukemia, elevated lactate dehydrogenase, or rapid clinical course. These are summarized in the mSMART classification of high-, intermediate-, and standard-risk disease.30 Approximately 20% of patients are high risk, 20% are intermediate risk, and 60% are standard risk. Median overall survival based on the last decade's data would suggest 2-3 years for high risk, 3-4 years for intermediate risk, and 8-10 years for standard risk. This will inevitably improve with novel therapies. A patient's risk status may indeed influence the selection of relapsed therapy; standard-risk patients may only require single-agent approaches, intermediate-risk patients likely benefit from bortezomib-containing regimens, and high-risk patients require more intense combination regimens to effectively control their disease.

Individualizing factors

In addition to risk status, several other patient factors (Table 2) should be considered because they may also influence treatment options. These include age, performance status, renal insufficiency, poor BM reserve (previous myelosuppression), neuropathy (preexisting), and other comorbidities such as cardiac disease and diabetes.

Other approaches

ASCT

ASCT remains the standard of care as frontline therapy in eligible patients, although many patients defer the transplantation (ie, collecting stem cells only) until first relapse.31 However, a second ASCT is also a very feasible approach as a salvage regimen later in the disease course if patients meet 3 criteria of having responded to the first ASCT, tolerated the first ASCT well, and have achieved at least 2 years of progression-free survival after ASCT.32,33

2. Allogeneic BM transplantation

Allogeneic BM transplantation with either fully myeloablative or reduced intensity conditioning remains an experimental approach in the relapsed setting due its significant toxicity, with a treatment-related mortality of 15%–30%, GVHD, and limited efficacy in controlling myeloma in the long term.34,35

3. High-dose chemotherapy (DT-PACE, DCEP)

In end-stage, multidrug resistant myeloma, very few options exist for disease control. Intense combination of chemotherapy often incorporating novel agents has been attempted with some success. The most commonly used regimen is DT-PACE, with studies demonstrating response rates of ∼50%; however, these responses remain short lived and are likely best used as a bridge to a more definitive therapy or clinical trial.36

Other considerations

Treating patients with relapsed myeloma will also involve much more than medical therapy. There is often a role for radiotherapy, generally for palliative pain control, plasmacytomas, or bulky extramedullary disease. This approach is generally adjunctive to medical therapy, but can significantly improve symptoms, quality of life, and even response.

Many patients with relapsed disease will no longer be treated with intravenous bisphosphonates. However, as recommended by the International Myeloma Working Group, they should be reinstituted at time of disease relapse.37

Other interventions for bony disease my include vertebroplasty, kyphoplasty, and surgery.

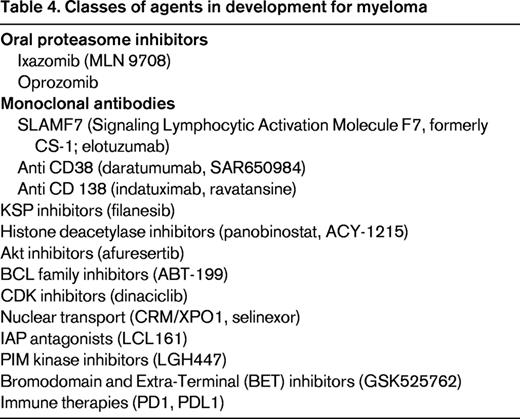

Emerging therapies

Based on the discovery and enhanced understanding of the pathobiology of the disease and with the dawn of several new biological agents, the future landscape of relapsed myeloma will likely be very different from the present.38 The classes of these new agents are summarized in Table 4. The most promising agents at present include ixazomib (an oral proteasome inhibitor), the monoclonal antibodies directed against CD38 (daratumumab and SAR 650984), elotuzumab, and the histone deacetylase inhibitors. However, novel targets and emerging agents, such as filanesib, selinexor, ABT-199, LCL 161, and immune therapies that target PD1 (Programmed Cell Death Protein 1) and PDL1 (Programmed Death-Ligand 1), are likely to increase our understanding of the disease and further extend survival in patients with relapsed myeloma.

Conclusion

Although multiple myeloma remains a mostly incurable disease, the improved survival rates achieved over the last decade are a reflection of enhanced therapies for both upfront and relapsed disease. As an increasing number of agents are available to the clinician, a deliberate and systematic strategy is required when treating patients with relapsed disease. The stepwise practical approach outlined in this chapter will maximize the use of current agents and, when incorporated with truly novel approaches, may herald further improvements in this disease.

Disclosures

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The author has received research funding from Onyx, Celgene, Sanofi, and Novartis. Off-label drug use: None disclosed.

Correspondence

Joseph Mikhael, MD, MED, FRCPC, Mayo Clinic in Arizona, 13400 E Shea Blvd, Scottsdale, AZ 85260; Phone: (480)301-8335; Fax: (480)301-4765; e-mail: mikhael.joseph@mayo.edu.