Abstract

Identification of large B-cell lymphomas that are “extra-aggressive” and may require therapy other than that used for diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, not otherwise specified (DLBCL, NOS), is of great interest. Large B-cell lymphomas with MYC plus BCL2 and/or BCL6 rearrangements, so-called ‘double hit’ (DHL) or ‘triple hit’ (THL) lymphomas, are one such group of cases often recognized using cytogenetic FISH studies. Whether features such as morphologic classification, BCL2 expression, or type of MYC translocation partner may mitigate the very adverse prognosis of DHL/THL is controversial. Classification of the DHL/THL is also controversial, with most either dividing them up between the DLBCL, NOS and B-cell lymphoma, unclassifiable, with features intermediate between DLBCL and Burkitt lymphoma (BCLU) categories or classifying at least the majority as BCLU. The BCLU category itself has many features that overlap those of DHL/THL. Currently, there is growing interest in the use of MYC and other immunohistochemistry either to help screen for DHL/THL or to identify “double-expressor” (DE) large B-cell lymphomas, defined in most studies as having ≥40% MYC+ and ≥50%-70% BCL2+ cells. DE large B-cell lymphomas are generally aggressive, although not as aggressive as DHL/THL, are more common than DHL/THL, and are more likely to have a nongerminal center phenotype. Whether single MYC rearrangements or MYC expression alone is of clinical importance is controversial. The field of the DHL/THL and DE large B-cell lymphomas is becoming more complex, with many issues left to resolve; however, great interest remains in identifying these cases while more is learned about them.

Learning Objective

To know the criteria being used for DHL and DE large B-cell lymphomas and the differences and similarities between these 2 groups of lymphomas

Introduction

The inspiration for this session comes from a great desire on the part of pathologists and clinicians to identify large B-cell lymphomas that cannot be categorized as one of the specific subtypes recognized in the 2008 World Health Organization (WHO) classification, but which are “extra-aggressive” and may require therapy different from that used for most other diffuse large B-cell lymphomas, not otherwise specified (DLBCL, NOS). Many of these cases end up being categorized either in the broad and heterogeneous category of DLBCL, NOS or, as will be discussed, in the newer category of B-cell lymphoma, unclassifiable, with features intermediate between DLBCL and Burkitt lymphoma (BCLU).1 An important subset of these cases are the “double-hit” lymphomas (DHLs), with MYC and BCL2 and/or BCL6 rearrangements identified based on cytogenetic testing. There is growing interest now in the more common “double-expressor” (DE) lymphomas defined based on immunohistochemical (IHC) stains with MYC and BCL2 staining on more than a specified proportion of tumor cells. Major issues that remain a hot topic of discussion are the precise definition for the DH and DE large B-cell lymphomas, whether there are important subsets of these cases that need to distinguished for clinical or biological purposes, whether MYC abnormalities in the absence of abnormalities involving BCL2 or BCL6 are just as ominous, what type of testing should be performed, how the DHL are best categorized once identified, and finally, of course, how they should be treated. Many of these frequently controversial questions are difficult to resolve because, in addition to the obvious issues of subjectivity (eg, with histopathologic classification), the literature is very inconsistent in terms of entry criteria for clinical studies, diagnostic criteria, phenotypic and cytogenetic criteria, and therapeutic strategies—an important issue that I will not keep reminding the reader about, but which may affect many of the reported discrepancies that I highlight.

What is a DHL?

DHL is defined on the basis of finding a MYC rearrangement together with specified other chromosomal rearrangements.2,3 At the present time, most use the term to refer to lymphomas with MYC plus BCL2 and/or, in ∼30% of the cases in the recent literature, BCL6 rearrangements (R) with the even less common lymphomas bearing all 3 rearrangements considered “triple-hit” lymphomas (THLs).4-7 The THLs are felt to be most similar to the BCL2 DHL cases.8 Some have included cases that have MYC with other chromosomal translocations, such as BCL3 at 9p13, or even CCND1.2 Conversely, many studies of DHL have not looked for BCL6-R, thus missing BCL6 DHL and THL.

Leaving the more controversial issues to the discussion in the following sections, DHLs are currently probably best restricted to either DLBCL, NOS or BCLU that cannot be better classified as a more specific type of lymphoma. For example, a mantle cell lymphoma with a MYC and CCND1 translocation should still be diagnosed as a mantle cell lymphoma even if the MYC-R has additional clinicopathologic implications.9 MYC and BCL2 rearrangements are also found in a very small proportion of follicular lymphomas (FL) and some B-lymphoblastic leukemias/lymphomas, particularly, cases representing transformation from FL, but still need to be diagnosed as a FL or B-lymphoblastic leukemias/lymphomas.8,10-13 Whether diffuse DH large B-cell lymphomas that represent transformation of a FL should be grouped with other DHL is controversial. Whereas one series showed a trend for a worse prognosis for the cases representing transformation, another found the presence of a preceding MYC-negative lymphoma not to make a difference (although, in that series, the overall survival was <6 months and most patients did not get Rituxan) and another showed no prognostic differences between patients with or without a prior history of lymphoma.10,14,15

It is also important to recognize that DHL is not a diagnosis recognized in the WHO classification, but rather a slang term for a large B-cell lymphoma with the translocations noted above. As defined in this way, 2%–12% of DLBCL (most studies ≤6%) and 32%–78% of BCLU are DHL, with the latter proportion being biased in some studies either because testing was performed on selected cases or because DH was used as a criterion for BCLU.4-7,15-25 The incidence of DH/THL increases with patient age.26

How are DHLs detected?

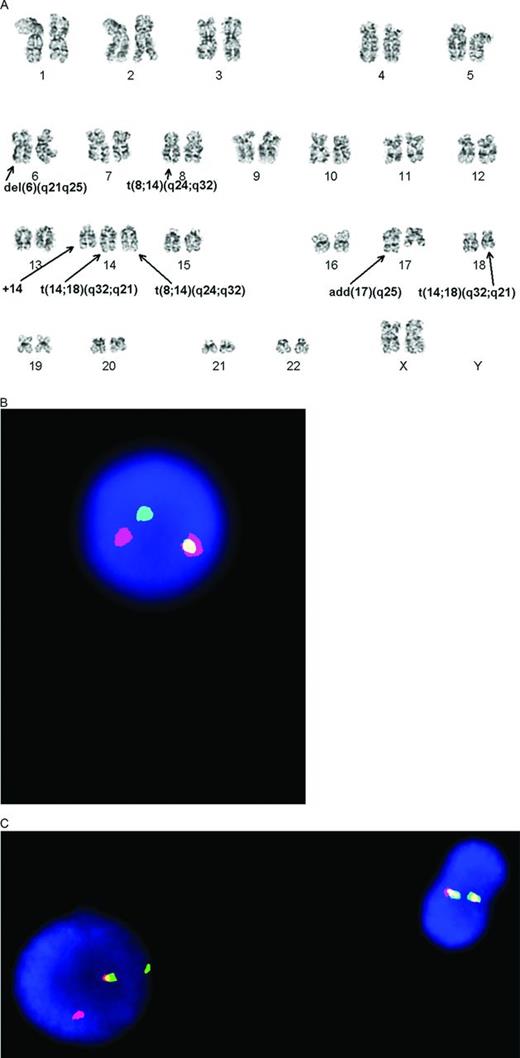

DHLs are detected using cytogenetic techniques. Many have been identified in the past using classical cytogenetic techniques (Figure 1A); however, these require fresh tissue, are labor intensive, and the reality is that, in many lymphomas, they will not have been performed. Although of great utility for varied reasons, specific genes involved in translocations are inferred but not proven [eg, t(14;18)(q32;q21) can represent either a BCL2 or MALT1 translocation] and cryptic translocations can also be missed. In one report, classical CG studies missed MYC-R in about half of the cases.27 Therefore, in most cases today, DHLs are detected using cytogenetic FISH studies with labeled probes targeting specific genes of interest (Figure 1B, 1C). FISH studies can be successfully performed in almost all cases using formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue sections, although smears, touch imprints, and fresh interphase or metaphase cells can also be used.4 Reproducibility is reported to be very high, with concordance among 2 observers >98% and, in another study, complete agreement for breaks (kappa = 1) and excellent agreement for gains (kappa = 0.89).5,7 Determination of the proportion of abnormal cells required for a positive result does vary somewhat between studies and can influence the overall results. “Break-apart” FISH probes are considered to be the most sensitive for picking up chromosomal rearrangements; however, they can be falsely negative depending on the site of the precise breakpoints. A minimal workup to find DHL includes use of a MYC break-apart probe and, if positive, BCL2 and, if negative, BCL6 break-apart probes. Use of a MYC/IGH dual fusion probe is useful in picking up occasional cases missed by the MYC break-apart probe and also in identifying the MYC partner in a subset of the cases (see discussion in the next section regarding potential importance of the MYC partner). In one study, MYC rearrangements were detected only with the dual fusion probe in 10% of the rearranged cases, in 38% only using the break-apart probe, and in 51% with both types of probes.7 Use of an IGH break-apart probe may also have some utility in identifying whether there might be a translocation involving an immunoglobulin (IG) gene.

Cytogenetic documentation of DHL. (A) Classical cytogenetics shows a complex karyotype with presumptive MYC/IGH and BCL2/IGH translocations. (B) The MYC translocation is confirmed with interphase FISH studies using a break-apart probe that shows one normal fused signal and one set of separated red and green signals. (C) The BCL2 translocation is confirmed with interphase FISH studies using a break-apart probe. There is one normal cell on the right with 2 fused signals and an abnormal cell with 1 fused and 1 set of separated red and green signals. (Figure contributed by U. Surti and M. Sherer.)

Cytogenetic documentation of DHL. (A) Classical cytogenetics shows a complex karyotype with presumptive MYC/IGH and BCL2/IGH translocations. (B) The MYC translocation is confirmed with interphase FISH studies using a break-apart probe that shows one normal fused signal and one set of separated red and green signals. (C) The BCL2 translocation is confirmed with interphase FISH studies using a break-apart probe. There is one normal cell on the right with 2 fused signals and an abnormal cell with 1 fused and 1 set of separated red and green signals. (Figure contributed by U. Surti and M. Sherer.)

What are the implications, associated controversies, and ongoing questions related to the DHLs?

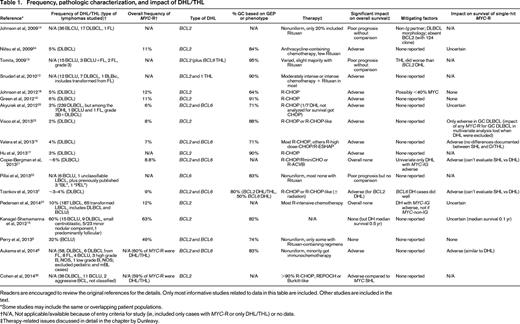

The conventional wisdom is that DHLs are very aggressive neoplasms that do not respond well to therapy, with descriptions such as “extremely dismal” or “grim” prognoses being used (Table 1).28,29 As defined in this discussion, there is a morphologic spectrum from many that bear some resemblance to Burkitt lymphomas (BLs) to probably a minority that more closely resemble DLBCL, NOS.13,14,30 In some series, however, only very few of the DHL/THL are categorized as BCLU.8 Phenotypically, they express B-cell antigens, with 64%–100% (most studies >80%) having a germinal center (GC) rather than a non-GC/activated B-cell (ABC) type phenotype/genotype as assessed mostly by IHC.6-8,10,12,13,15-19,22,23,27,30-34 The BCL6 DHL are similar in many ways to the BCL2 DHL except that they are more likely to be CD10- (36% vs ∼10%) but IRF4/MUM-1+ (75% vs ∼18%), only infrequently express BCL2 (22% BCL2+ vs ∼92%), and may have less cytogenetic complexity.32 Another study with different IHC cutoff values also found less common CD10 and BCL2 and more frequent IRF4/MUM1 expression among the BCL6 DH, but did report a lower proportion of GC (vs ABC and nonclassifiable) cases and, as one might expect, a higher proportion of cases that were not associated with a FL.8

Frequency, pathologic characterization, and impact of DHL/THL

Readers are encouraged to review the original references for the details. Only most informative studies related to data in this table are included. Other studies are included in the text.

*Some studies may include the same or overlapping patient populations.

†N/A, Not applicable/available because of entry criteria for study (ie, included only cases with MYC-R or only DHL/THL) or no data.

‡Therapy-related issues discussed in detail in the chapter by Dunleavy.

Median survivals are often in months, with most reported to be no more than ∼1.5 years and with overall survivals at 3 or 5 years shorter than expected with DLBCL, NOS.6,10,12-14,16-19,25,32-35 However, some do not find it to be an independent prognostic indicator.7,21,35 Both BCL2 and BCL6 DHL are aggressive, with one report suggesting that the latter patients may have an even more aggressive neoplasm and another finding that THLs were more aggressive than BCL2 DHLs.8,13,32 However, one recent study that included only 4 BCL6 DHL patients reported that they did well.7 A larger series from the same institution that included cases with extra copies of MYC, BCL2, or BCL6 also as DHL did not find a difference between cases with BCL2 or BCL6 abnormalities.36 A review of BL in the Mitelman cytogenetic database also supports that the DHL/THL cases must be distinguished from BL cases despite their MYC rearrangements and oftentimes morphologic and phenotypic overlap.3 The patients with DHL/THL were much older than other BL patients, the degree of genomic complexity was significantly greater, and there were different associated “nonrecurrent” cytogenetic abnormalities. These investigators concluded that the DHL/THL previously diagnosed as BL are a “very aggressive disease that is refractory to current chemotherapeutic treatment. Overall survival is very short….”3

Unfortunately, the situation has become much more complex because, as might be expected by some long-term survivors in some reports, the very adverse prognosis may be mitigated by other factors. Some report that cases that morphologically resemble DLBCL rather than BCLU do better,14 although others find that the specific morphologic findings do not have prognostic implications.10,35 Two studies of BCLU (or closely related lymphomas) with an overall poor prognosis did not show a significantly adverse prognosis for those with a DHL, perhaps related to the very aggressive nature of most BCLU cases.6,15 The infrequent cases lacking BCL2 protein expression are also reported to be not as aggressive.14 Low MYC expression may also mitigate the very adverse prognosis of DHL cases. Two of 3 long-term DHL survivors in one study had <40% MYC+ cells and another reported that 5 of 8 patients with MYC-R but little MYC staining did not have “events.”5,18 The question is thus raised as to whether, as with BCL2, lack of significant MYC protein expression may mitigate the effect of the MYC-R or DH cytogenetics. Another study found a significant impact only among those with a GC phenotype.25

More recent attention has focused on the apparent importance of the MYC partner. In a study of patients with DLBCL or BCLU, most but not all of whom received intensive therapy and Rituxan, only when DHL with an IG MYC partner were studied did they have an adverse prognosis.37 Neither DHL as a whole nor the non-IG/MYC DHL had an adverse prognosis. Half of the MYC rearranged cases had an IG partner that was IGH in 58% of the translocated cases or either κ or λ. A study of de novo DLBCL treated with immunochemotherapy published in abstract form also reported that only DHL with an IG/MYC translocation had an adverse prognosis.21 These studies would suggest that, in the presence of a MYC translocation, one must do MYC/IGH FISH and, if there is no evidence of an IGH translocation partner, use break-apart FISH probes for κ and λ, with the latter identifying more cases than the former.33 Caution is advised at this time because dual fusion probes for MYC/κ and MYC/λ are not available so that finding an MYC and light chain rearrangement does not necessarily mean they are each other's partner. Of greater concern, one study of a mixed group of cases excluding “molecular BL” (mBL) and pediatric cases and with most patients not having received immunochemotherapy did not find a prognostic impact of the MYC partner looking at DHL or cases with an isolated MYC rearrangement, precluding making a final conclusion about this topic.8 This study found slightly higher MYC levels in the MYC-IG cases and a lower proportion of BCL6+ cases, but otherwise the 2 groups had very similar gene expression profiles; similar IGH, BCL6, and MYC mutational profiles and genomic complexity; and a similar distribution of morphologic categories.

Although all of these findings suggest that we should possibly narrow our definition of clinically meaningful DHL, based on a limited number of cases, others have suggested broadening the definition to include cases with MYC or BCL2 rearrangements plus extra copies of the nonrearranged gene.10,24 This definition was subsequently used for a large series of what were still termed DHLs from that institution, and they reported that it did not matter whether there was a rearrangement or extra copies of these genes.36 Caution is advised because, at least as a single parameter, patients with DLBCL and MYC amplifications (>4 copies of MYC) do poorly, but not those with MYC gains (3-4 copies of MYC), which are much more common.16 Although based on only 3 cases, others have reported no impact of “high-level” MYC amplifications (≥6 gene signals or tight clusters of at least 5/cell).7

A more vexing question is whether the DHL category should be merged with the group of large B-cell lymphomas that have a MYC-R without a BCL2 or BCL6 rearrangement, so-called “single-hit” lymphomas (SHLs). Many of the earlier studies reporting the adverse impact of MYC-R included both SHL and DHL without necessarily distinguishing them. MYC-R are reported in ∼6%-14% of DLBCL and in 33%–91% of BCLU.5-7,16,18-22,24,25,38,39 The majority are found in the setting of a DHL; however, 17%–75% are SHL, with the majority of studies reporting between 30% and <50%.5-8,16,19-25,27,37,40 SHLs have been reported to be as aggressive as DHL or at least an adverse prognostic indicator,8,15,16,20,21,24,27 but others report that DHL lymphomas are more aggressive.18,19,23,27,35 In fact, some report that isolated MYC-Rs are not associated with an adverse prognosis at all6,18,19 or are so only in cases of GC type (impact of any MYC-R lost in multivariate analysis once DHL are excluded).23 Some of these studies have excluded subsets of DHL based on their entry criteria, a major problem with this field. Adding additional potential complexities to these analyses, it has also been reported that the best prognostic indicator related to MYC-R, DHL, or DE DLBCL is the combination of a MYC-R plus high (>75%) MYC expression, which is associated with a median survival of only 10 months versus 77 months for those with low MYC expression.7 In fact, MYC-R did not have a prognostic impact if there was <50% MYC+ cells. Nevertheless, these investigators stated that “… so-called genetic double-hit lymphomas … represent a true oncological challenge and are clearly under-treated by R-CHOP.” Further contributing to the complexity here, it has been reported that, although MYC-R DLBCL cases of GC type have a distinctive GEP signature, the MYC signature is not seen in the ABC cases.7

How should the DHLs be categorized in the 2008 WHO classification and what controversies and ongoing questions arise?

Categorization of DHL is controversial. The major options are putting all DHL in the DLBCL, NOS category and then noting the DH, putting all the cases in the BCLU category even if they morphologically resemble a DLBCL, dividing up the DHL cases with some in each of these 2 categories based on their morphologic appearance, or establishing a new provisional “DHL” category.15 Practice patterns vary widely, even at academic institutions, with many choosing either the second or third options, but with some now promoting the first. Given the uncertainty as to whether morphologic differences matter when it comes to the outcome and potential therapy for DHL, the current interest in identifying DHL and the great overlap between the DHL and BCLU cases from many perspectives, one could argue that now it is best to put all DHL cases in the BCLU category rather than dividing them up based on a subjective, probably not very reproducible, morphologic distinction.

BCLU, which some use to describe most, if not all, of their DHL cases, was introduced in the 2008 WHO classification, not as a new entity, but as a somewhat vaguely defined and heterogeneous category for cases that have features intermediate between DLBCL and BL.1,4,6,15,34,40 BCLU is considered a very aggressive lymphoma; however, the literature is not completely consistent, with one study reporting a median survival of only 9 months (albeit with some long-term survivors) and another reporting no definite differences in survival between patients with DLBCL, NOS and BCLU.6,40

The BCLU category does not simply reflect the inadequacies of modern-day hematopathologists, but acknowledges a gray zone also documented by gene expression profiling (GEP), which has shown the existence of a group of lymphomas intermediate between mBL and DLBCL, clearly not of BL type.41 Even the mBL category, however, includes some cases unlike classic BL. Cases of mBL that had a histomorphological diagnosis of DLBCL or high-grade B-cell lymphoma, NOS had genetic findings unlike BL or DLBCL, included some DHL (which is not acceptable for BL), occurred in older patients compared with BL, and, although they were not all treated with intensified treatment regimens, appeared to have a “dramatically different and usually rapidly fatal” clinical course unlike BL, with a median survival of only 0.58 years.42

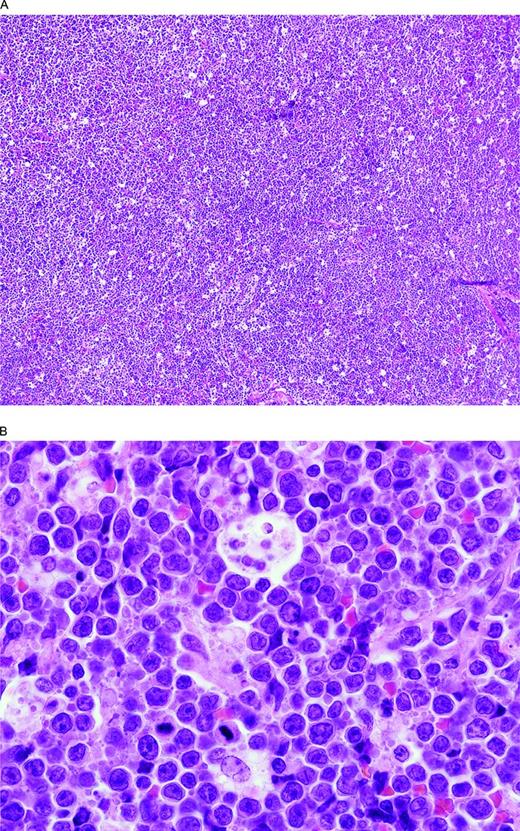

It is very difficult to define exactly what cases belong in this intermediate category. A general guideline is to include cases that look like BL but in which the phenotype, genotype, and/or karyotype are too “atypical” or cases with perfect ancillary studies but cytologic features considered beyond what is acceptable for even what used to be called “atypical” BL (Figures 2, 3). In a group of 48 cases we reviewed, the most frequent differences from a BL included more pleomorphism and fewer typical intermediate-sized cells and either no starry sky or more often only a partial starry sky appearance, a lack of amphophilic cytoplasm, and the presence of coagulative necrosis (SHS, unpublished data). Some use the category for at least a subset of the blastoid-appearing mature B-cell lymphomas that others might include as blastoid-appearing DLBCL, NOS or blastoid-appearing transformed follicular lymphomas. Phenotypically, most cases were CD10+ as with BL but, unlike typical BL, about half of the cases were BCL2+ and the Ki-67 often high but <95% in most. Therefore, most cases will have a GC phenotype and, if misdiagnosed as DLBCL, NOS, one might think the patient had a more indolent large B-cell lymphoma when, in fact, according to many but not all studies, they have a very aggressive one. Consistent with the premise that BCLU is not used uniformly, the proportion of BCLU with MYC rearrangements varies widely in the literature from 33% to 91% (or “most”), with 78% reported in one study to be DHL.4,24,38,39 Compared with DLBCL, BCLU has more MYC-R, but fewer BCL6-R, and, compared with BL, fewer MYC-R and more BCL6-R and BCL2-R. Consistent with this finding, the intermediate group of lymphomas between BL and DLBCL identified by GEP is reported to have MYC-R in 53% of the intermediate cases and, unlike classic BL, includes cases with BCL2-R or BCL6-R.41 Furthermore, unlike BL, which was mostly “MYC simple” (MYC/IGH, <6 abnormalities by array comparative genomic hybridization, aCGH, no DHL), most of the intermediate cases with MYC rearrangements were “MYC complex” (MYC/non-IGH and/or ≥ 6 abnormalities by aCGH and/or a DHL).41 Further support for the concept that at least a subset of DHL cases have distinctive features that overlap with BL comes from the report that ID3 mutations, reported in 38%–68% of BL but absent in DLBCL cases,43 are also present in 21% of BCL2 and 25% of BCL6 DHL cases.30 Additional support for the concept of a group of cases truly intermediate between BL and DLBCL comes from the observation that ID3 mutations are also found in 21% of aggressive lymphomas with an intermediate gene expression profile between BL and DLBCL, although these cases had clinicopathologic features more like BL.44 In another study, patients with ID3-mutated DLBCL or BCLU were not significantly younger than those without the mutation.30 Similarly, TP53 mutations are reported in 35% of DHL/THL (only 1/16 BCL6 DHL) compared with 55.6% of BL cases and only 15% of GCB-type DLBCL cases, further supporting the concept of a group of lymphomas intermediate between BL and DLBCL.28

BCLU with MYC and BCL6 double-hit. (A) There is a diffuse proliferation with a starry sky pattern due to tingible body macrophages like in a BL. (B) At high magnification, note the rather monotonous proliferation of intermediate-size transformed cells and scattered tingible body macrophages. Although resembling a BL, there are more cells with single central nucleoli than would be typical and some irregular nuclear contours. The Ki-67 stain was extremely high but, unlike BL, the cells were CD10 negative and BCL2 positive (not illustrated).

BCLU with MYC and BCL6 double-hit. (A) There is a diffuse proliferation with a starry sky pattern due to tingible body macrophages like in a BL. (B) At high magnification, note the rather monotonous proliferation of intermediate-size transformed cells and scattered tingible body macrophages. Although resembling a BL, there are more cells with single central nucleoli than would be typical and some irregular nuclear contours. The Ki-67 stain was extremely high but, unlike BL, the cells were CD10 negative and BCL2 positive (not illustrated).

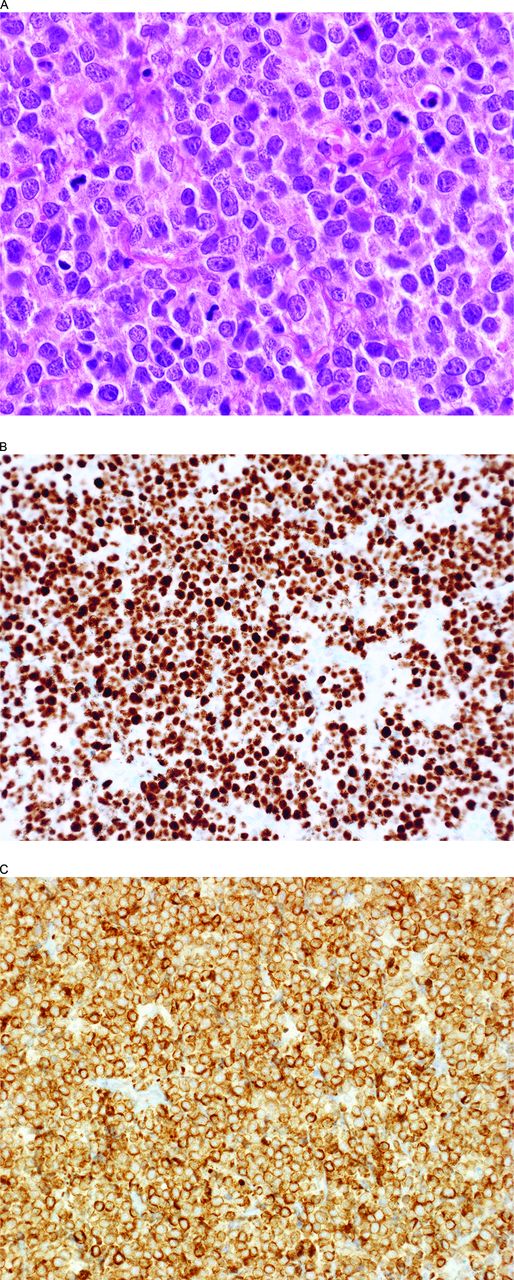

BCLU with MYC and BCL2 double-hit and MYC and BCL2 expression (DE). (A) This lymphoma has somewhat blastoid nuclei and a high mitotic rate. Note the extensive nuclear MYC (B) and cytoplasmic BCL2 (C) expression fulfilling the criteria for a DE B-cell lymphoma. The lymphoma had a GC-type phenotype (CD10+, BCL6+, IRF4/MUM1−) and >95% Ki-67-positive cells (not illustrated).

BCLU with MYC and BCL2 double-hit and MYC and BCL2 expression (DE). (A) This lymphoma has somewhat blastoid nuclei and a high mitotic rate. Note the extensive nuclear MYC (B) and cytoplasmic BCL2 (C) expression fulfilling the criteria for a DE B-cell lymphoma. The lymphoma had a GC-type phenotype (CD10+, BCL6+, IRF4/MUM1−) and >95% Ki-67-positive cells (not illustrated).

What is the role of IHC, the implications of DE large B-cell lymphomas, pitfalls, and unsettled issues?

Immunophenotypic studies have several potential roles to play in this arena, but also some serious potential pitfalls and unsettled issues. First, IHC and, to a lesser extent, flow cytometric studies have been proposed as rapid and cost-effective screening tools to cut down on the number of FISH studies being used to find DHL/THL. In fact, many have looked for DHL/THL only in BCLU and/or when large B-cell lymphomas have a very high proliferation fraction based on Ki-67 staining, but both strategies will miss a significant minority of DHL/THL. Some DHL/THL cases morphologically resemble other DLBCL cases and many have <90% Ki-67+ cells, with some much lower. With a Ki-67 cutoff of >90%, the sensitivity for finding DHL/THL among aggressive B-cell lymphomas was only 0.54 and, with >75%, still only 0.77 (with a specificity in a group that did also include BL of 0.62 and 0.36).45 Another series looking only at DH DLBCL found that only 7% had a Ki-67 >90%.18 Others have also reported lower Ki-67 proportions ranging from ≤60%-90% in 21%–57% of DHL/TLH cases, with the 57% from a study using a cutoff of 80%6,12-14,30,32,34 or have found no difference between DHL and non-DHL.27 Conversely, one small series found only one DHL (14%) to have a Ki-67 <80%.25 BCLU cases are among those more likely to have a higher Ki-67.10 Compounding this issue is the reported poor reproducibility of Ki-67 IHC staining.46 Although beyond the scope of this review, several studies have reported that Ki-67 did not affect survival.14,20,47 Flow cytometric demonstration of dim CD20 and/or dim CD19 to help identify DHL has also been reported, but others find it to be of limited utility because most cases do not have these features.48-50

But what about the role of MYC IHC? It has been reported that finding ≥70% MYC+ cells had a sensitivity of 100% and specificity of 93% for a MYC break.51 Another recent study reported that their maximum specificity/sensitivity was achieved using a >95% cutoff; however, it yielded a sensitivity of 91% and a specificity of only 36%, with a 60% positive predictive value.7 Sixty-four percent of their MYC-R cases fell in their low MYC expression group and they noted that neither MYC protein expression nor any clinicopathologic variable could be used to predict the presence of a MYC-R. Others have also found that MYC IHC cannot be relied upon to pick up all of the DHL cases and agree that the specificity of finding many MYC+ cells is <100%. Reports include finding <50% MYC+ cells in 41% of MYC-R cases,6 <40% MYC+ cells in 29% of DHL cases,18 and <30% MYC+ cells in 17% of MYC-R cases.16 Another study in which 31% of MYC-R cases were MYC-low suggested that MYC FISH testing should only be omitted if there are <20% MYC+ cells so as to not miss too many cases (still with only a sensitivity of 92.3%).5 One abstract even reported finding <50% MYC+ cells in 42% of BL.52 Concordance among 3 pathologists of 94% for MYC IHC has been reported, with assessment considered “robust” and with little effect of variations from different fixation techniques at different institutions, and another investigation found differences of >1 decile among 2 observers in only 7% of cases.18,19 However, the variably reported results in the literature suggest that staining varies between different laboratories and, in my experience, staining within even BL can vary based on cell viability and probably fixation-related issues. Problems with reproducibility in the use of the 40% cutoff have also been reported53 and Horn et al did write in 2013 that: “paying tribute to the fact that only recent and as yet incomplete experience has been gained for immunohistochemical stainings with the anti-MYC antibody … at the moment we strongly advise the use of a combined MYC-FISH and IHC model.”5 Furthermore, even if perfect, MYC IHC could only be used as a screen for DHL because they also require BCL2 and/or BCL6-R and neither can be predicted based on BCL2 or BCL6 expression.

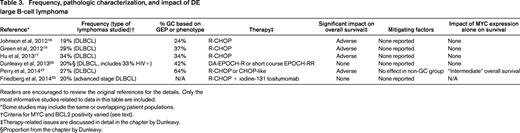

Therefore, to find DHL/THL requires relatively liberal use of cytogenetic FISH testing. In an effort to control costs and save time, it has been suggested that a reasonable strategy is to screen the BCLU cases plus DLBCL with a GC phenotype.31 Some would propose selecting one or more immunohistochemical/morphologic features that have been associated with DHL as a screen, even if recognized to be imperfect (Table 2). Others still recommend screening all DLBCL and BCLU cases for MYC rearrangements.8,27 A recent review also notes that “it is reasonable to consider testing for MYC and BCL2 rearrangements by FISH for all newly diagnosed DLBCL.”29

Suggested evaluation of large B-cell lymphomas of DLBCL, NOS, and BCLU type

*In addition to its importance in arriving at a precise diagnosis (eg, is disease restricted to mediastinum?), the clinical setting may affect possible therapeutic options and thus could influence the extent of a clinically applicable workup. Specifically, a workup to determine if very aggressive therapies are appropriate is not required if a patient's performance status or other circumstances would preclude such a therapeutic approach.

†It is very difficult to provide the proportion of cases that would be missed using each of these parameters due to the wide variations reported in the literature and, in some situations, a limited amount of data (see text). The criteria, which at least in some studies would be the least predictive, are morphologic features and Ki-67 proportions and for the less common BCL6 DHL, BCL2 expression. Problems with MYC staining are discussed in the text.

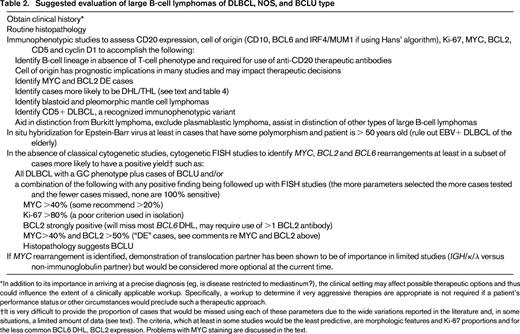

But can we skip doing FISH studies altogether? There is great interest today in DE DLBCL, cases with more than a specified proportion of MYC+ and BCL2+ cells (Figure 3, Table 3).5,16-19,47,54,55 DE DLBCL are associated with other high-risk clinical parameters and have an often demonstrably independent adverse prognosis compared with other DLBCL, although they are not as aggressive as DHL, with 3-year overall survivals of 43% and 5-year survivals of only 30%–36% reported.17-19,47 Survival differences in patients with BCLU are not identified, but there are a limited number of cases reported.6 Significant survival differences were also not identified among a relatively small number of patients in a study of advanced-stage DLBCL or in a study of DLBCL that included 33% HIV+ patients.55,56

Frequency, pathologic characterization, and impact of DE large B-cell lymphoma

Readers are encouraged to review the original references for the details. Only the most informative studies related to data in this table are included.

*Some studies may include the same or overlapping patient populations.

†Criteria for MYC and BCL2 positivity varied (see text).

‡Therapy-related issues are discussed in detail in the chapter by Dunleavy.

§Proportion from the chapter by Dunleavy.

It is important to recognize that the DE lymphomas are not equivalent to DHL/THL, even if ∼80%-90% of the DHL/THL cases are also DE.17,19 Furthermore, most BCL6 DHL cases are excluded from the DE category because they are often BCL2 negative by IHC.32 Nevertheless, some have used the term “double hit … by immunohistochemistry.”55 DE lymphomas are much more common than DHL, with <20% of DE lymphomas DHL.19 Nineteen percent to 34% of DLBCL cases16-19 and 20% of DLBCL/BCLU cases40 are reported to be DE lymphomas. Unlike the GC predominance in cytogenetically defined DHL, most studies find that ∼2/3 of DE DLBCL cases are of the non-GC type.17-19,32

The potential importance of DE large B-cell lymphomas has been emphasized, with one report that the prognostic differences between GC and ABC/non-GC DLBCL relate to the latter having more DE cases and that, once the DE cases are excluded, there are very limited differences in GEP between GC and ABC DLBCL.17 Another report found that, whereas DE has an impact in both the GC and non-GC groups, cell of origin falls out as a prognostic marker for overall survival in a model that also includes International Prognostic Index scores.19 Yet another study did not find prognostic implications in the non-GC group, but this was thought to be due to a low statistical power.47

Complicating interpretation of the literature, although most studies use a cutoff of 40% for MYC IHC positivity (with one using 10% and another 30%), cutoffs for BCL2 have ranged from >0 to ≥70%, but with most requiring at least 50%.5,16-19,47 Two studies that reanalyzed their data using others' cutoffs for either BCL2 or MYC led to loss of significant independent or univariate prognostic differences.16,47 Another issue is significant concern about the reproducibility of BCL2 staining and its interpretation, although several studies have reported high levels (>90%) of agreement among small numbers of observers.18,19,46,47,54 Because of this concern, an editorial about the 2 first high-profile DE studies noted that “for the time being, the diagnosis of MYC/BCL2 double-protein-expressing DLBCL should be made only by internationally recognized hematopathologists.”54 Aside from its impracticality, I hesitate to speculate on the reproducibility of selecting “internationally recognized hematopathologists.” Despite these confounding issues, some clinicians are already making treatment decisions based on whether a DLBCL is a DE lymphoma. A recent review of prognostic factors in DLBCL, however, did not recommend looking for DE lymphomas because “it is not known if its presence necessitates a change in front-line therapy.”29 They also wrote that, because DE cases are relatively common, it “may not be feasible to treat so many patients with more intensive therapy when a large portion may otherwise achieve a CR with standard R-CHOP.”29 The significant issues related to the reproducibility in MYC staining and interpretation are discussed in the second paragraph of this section, but also must be considered. I must admit that I find it somewhat frightening that deciding whether there are slightly more or slightly less than 40% MYC+ cells in a BCL2+ large B-cell lymphoma could make a major difference in a patient's treatment plan and such decisions are not uncommon in my daily practice.

Perhaps analogous to the cytogenetic story, some find that MYC expression by itself (>40%) is an adverse prognostic indicator that is independent of BCL2 expression, but others do not or found it mattered only in their patients who received R-CHOP.5,16-19,40 One study even found, however, that the patients with isolated MYC expression did better than the other groups studied!18

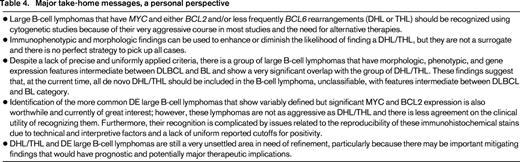

Conclusion

Although many unresolved and contentious issues remain with regard to the DHL/THL and DE large B-cell lymphomas, and although some report that simple identification of MYC rearrangements or extensive MYC expression is sufficient, identification of these cases remains of great interest (Table 4). At the present time, the most definite and objective finding that many believe should affect therapeutic strategies remains the identification of the very aggressive DHL/THL. This can be inferred from classical cytogenetic studies, but otherwise requires cytogenetic FISH studies, which should at a minimum be performed in the subset of large B-cell lymphomas with an enhanced chance of having MYC and BCL2 and/or BCL6 translocations. The identification of the DE cases is also of interest largely for prognostic purposes, but it is not a surrogate for finding DHL/THL. Future studies should help to clarify the best criteria for the recognition of DHL/THL and DE lymphomas and which features might mitigate their implied aggressive behavior, further our understanding of their biologic correlates, and better define the role of the BCLU category in the 2008 WHO classification, which is currently undergoing revision. Most importantly, whether their recognition can lead to improved patient outcomes remains our most critical goal.

Disclosures

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The author declares no competing financial interests. Off-label drug use: None disclosed.

Correspondence

Steven H. Swerdlow, MD, Professor of Pathology, Director, Division of Hematopathology, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, UPMC Presbyterian, 200 Lothrop St, G-335, Pittsburgh, PA 15213; Phone: (412)647-5191; Fax: (412)647-4008; e-mail: swerdlowsh@upmc.edu.