Abstract

Incidental pulmonary embolism (IPE) is a management challenge for the unsuspecting clinician. Patients with IPE frequently have signs or symptoms that are unrecognized as PE related, and their clots occur predominantly in the proximal pulmonary vasculature. There is uniformity in recommending anticoagulation for patients with IPE proximal to the subsegmental pulmonary vasculature, but prospective data are not currently available to guide the duration of therapy in this population. Several studies suggest that outcomes, including recurrence, mortality, and bleeding, are similar for patients with IPE and suspected PE, especially among those who also have cancer. Patients with isolated incidental subsegmental pulmonary embolism (ISSPE) are particularly challenging because some studies suggest that they can be managed without anticoagulation. Therefore, an algorithm is proposed to guide the evaluation and treatment of patients with ISSPE.

Learning Objectives

Describe risk factors that increase the likelihood of identifying incidental pulmonary embolism (IPE)

Develop an algorithm to evaluate and manage patients with IPE, particularly those with ISSPE

Summarize currently available data regarding the prognostic implication of ISSPE among patients with and without concurrent malignancy

A considerable amount of data is now available in the medical literature highlighting the modern problem of incidentally detected pulmonary embolism (PE) identified on multirow detector computed tomography (CT) scans performed for reasons other than evaluation for PE. These data show that the identification of incidental PE (IPE) increases with the following: (1) decreasing slice thickness of the scanner1 ; (2) more proximal location of the PE2 ; (3) inpatient hospitalization; (4) a cancer diagnosis; and (5) age.3 As many as 50% of such clots are found in the main and lobar pulmonary arteries, prompting urgent notification of the unsuspecting practitioner.4-6 However, a majority of patients with IPE, both with and without concurrent malignancy, have PE-related signs or report symptoms, such as shortness of breath and fatigue, to someone on the medical team.4-6 Symptoms may, in fact, correlate with poorer survival among cancer patients with IPE compared with those who are truly asymptomatic.7 It is not known how symptoms and anticoagulation interact to affect survival. To distinguish patients with IPE who actually have PE-related signs or symptoms that were overlooked or misattributed from symptomatic patients who are evaluated for PE with dedicated CT pulmonary angiography (CTPA), the latter group will be referred to as having suspected PE (SPE) throughout this review.

Unfortunately, available data regarding relevant outcomes for patients with IPE, including recurrence, treatment-related bleeding, and survival, are almost entirely based on retrospective studies. Nonetheless, the most recent American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP) guidelines recommend following the same anticoagulation algorithm for patients with IPE proximal to the subsegmental pulmonary arteries as is proposed for patients with symptomatic PE.8 PE identified in the main, lobar, and/or segmental pulmonary arteries will be referred to as proximal PE/IPE in this review. Whether anticoagulation therapy should also be offered to patients with isolated incidental subsegmental PE (ISSPE) is not clear. Several studies suggest that this entity may be more clinically significant among patients with cancer than among patients scanned for other indications.7,9-11

It appears that clinical practice is consistent with current guidelines for proximal IPE, but there is clearly a lack of certainty with regard to duration of anticoagulation and its use among patients with ISSPE. A recent international survey indicates that the majority of internists, oncologists, and hematologists would recommend anticoagulation for a patient with a newly diagnosed, truly asymptomatic proximal IPE (>97%), regardless of whether malignancy was also present.12 There was less agreement with regard to treating an asymptomatic patient with ISSPE; a greater number of respondents said they would recommend anticoagulation to such a patient if they had a concurrent malignancy than if they did not (89% versus 72%). Greater heterogeneity in practice was revealed when the respondents were asked about the recommended duration of anticoagulation. For patients without cancer, few respondents recommended indefinite anticoagulation, although the number was higher if the patient had a central IPE than a segmental or subsegmental IPE (9.0% vs 5.1% and 5.6%, respectively). For patients with a concurrent malignancy, proximity of the clot appeared to have the greatest effect on treatment duration, with 62.7% of participants recommending indefinite anticoagulation for patients with central IPE, 52% for patients with segmental IPE, and 42.6% for patients with ISSPE. Importantly, the majority of clinicians who opted to withhold anticoagulation for IPE changed their recommendation in favor of anticoagulation if a deep venous thrombosis (DVT) was identified. This study did not indicate how many clinicians currently routinely check for DVT when IPE is diagnosed, but the available literature suggests that this is not done routinely. Unfortunately, there is no prospective study to support or refute the utility or cost/benefit ratio of lower-extremity venous ultrasonography in this population.

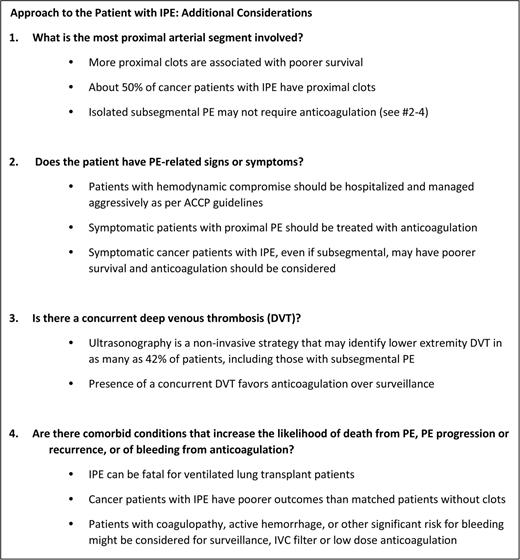

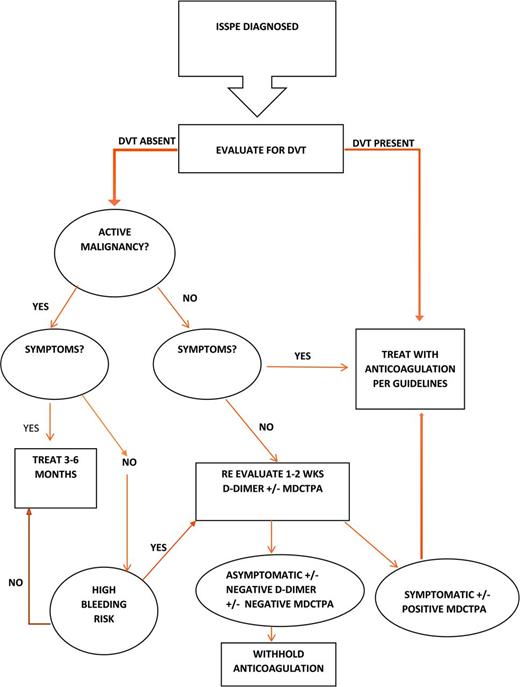

In this review, currently available data are used to generate 4 simple considerations with which to approach the patient with newly diagnosed IPE (Figure 1). A more detailed algorithm is proposed for evaluating patients with ISSPE, for which there is less agreement as to the most appropriate management (Figure 2). Additional prospective treatment data are needed to offer high-level recommendations about the duration of therapy in all patients with IPE, particularly for those with ISSPE. Therefore, the recommendations proposed for the evaluation and management of ISSPE are grade 2C (weak, with low-quality evidence) but provide a helpful algorithm for clinicians to weigh the risks and benefits of anticoagulation.

Consideration 1: what is the most proximal location of the IPE?

A meta-analysis of available studies suggests that IPE involves the proximal pulmonary arteries in a majority of cases.3 In a retrospective analysis of hospitalized patients with IPE and SPE, there was no significant difference in the location of the most proximal PE between the two groups.6 Among cancer patients with IPE, approximately half have central (main or lobar) PE.4,5 PE located in the main and lobar pulmonary arteries is generally associated with greater morbidity and mortality. In a meta-analysis of trials that reported mortality after SPE, the presence of centrally located PE conferred an odds ratio of 2.24 for death at 30 days (95% confidence interval, 1.29-3.89).13 Similarly, we have shown among mostly ambulatory cancer patients that survival probability drops significantly with more proximal IPE, whereas the survival of cancer patients with ISSPE appears to be similar to matched patients without PE.14 The presence of a centrally located PE may factor into the initial risk assessment of a patient with PE and into choosing to hospitalize during the initial treatment period, but it does not alter the type, dose, or duration of therapy that is recommended currently.8

However, there is less certainty about the urgent need for anticoagulation among patients with ISSPE. In a retrospective review of symptomatic patients with SSPE, 22 were left untreated and suffered no venous thromboembolism (VTE) recurrence, bleeding, or death at 3 months.9 In another study of symptomatic patients, the authors failed to identify poorer outcomes in terms of 3-month recurrent VTE among those patients ruled out for PE and therefore not anticoagulated, with single-row detector CT. Because these scans miss approximate 5% of SSPE,11 the authors imply that the undetected SSPE were clinically irrelevant. These data conflict with the bulk of evidence regarding outcomes for SSPE patients with cancer. Den Exter et al10 found no difference between symptomatic cancer patients with SSPE and those with more proximal PE in terms of 3-month VTE recurrence, bleeding, and death.

Therefore, it is currently recommended and appears to be widely accepted by treating physicians that patients with proximal IPE merit systemic anticoagulation. Patients with ISSPE involving multiple arteries and those who also have cancer may benefit from anticoagulation, but it is critical to examine and discuss with the patient the risk of bleeding and potential effect on quality of life posed by anticoagulation.8 Furthermore, there is greater likelihood of false-positive diagnoses with single and more distal IPE.1,2 Therefore, clinicians need additional tools to either build a case for or opt against systemic anticoagulation, especially for patients with ISSPE. These tools include evaluation for presence of PE-related signs or symptoms and performance of lower-extremity venous ultrasonography to identify concurrent DVT, which are discussed below. D-dimer has low specificity but has excellent sensitivity for ruling out PE in patients with and without cancer;15 however, it is not considered reliable in ruling out DVT among patients with cancer.16 Therefore, a negative D dimer may suggest the possibility of a false-positive CT finding of IPE and/or may support withholding anticoagulation in a truly asymptomatic patient with ISSPE who does not have concurrent DVT.

Consideration 2: does the patient have signs or symptoms of PE?

Patients with IPE who demonstrate signs of hemodynamic instability should be managed aggressively and no differently from patients with SPE. As mentioned above, many patients diagnosed with IPE are actually symptomatic,4-6 and fatigue, in particular, may be misattributed to other factors, such as concurrent malignancy or other comorbidities.4 However, we have demonstrated that, among cancer patients with IPE, including those with ISSPE, symptoms are associated with poorer survival.7 Based on these and other published data, the Scientific Subcommittee on Haemostasis and Malignancy of the Internal Society of Thrombosis and Haemostasis recommends treatment with anticoagulation for all cancer patients with VTE who have thrombosis-related symptoms.17 It is reasonable to postulate that it is safe to withhold anticoagulation from truly asymptomatic patients with isolated ISSPE, especially among those without concurrent DVT or malignancy. However, such patients should be educated about the signs and symptoms of VTE and instructed to seek immediate medical attention should such occur. It is also advisable, particularly among patients with VTE risk factors such as malignancy, to reevaluate clinically within 1-2 weeks. Performance of a dedicated CTPA is reasonable if PE-related signs or symptoms arise on close follow-up (Figure 2).

Consideration 3: is there evidence of concurrent DVT?

Performance of bilateral lower-extremity ultrasonography is a noninvasive approach for identifying thrombus outside of the lung that may be useful in justifying anticoagulation among patients with peripheral IPE. In the event that the study cannot be performed immediately, anticoagulation therapy should not be delayed if otherwise indicated. Interestingly, this tool has been low-yield for patients undergoing evaluation for PE but without signs or symptoms of DVT;18 but, ultrasonography has never been studied systematically in patients diagnosed with IPE. In a study of 19 outpatients with cancer and IPE who were compared with a control group of 19 patients presenting to the emergency department with SPE, ultrasonography of the lower limbs was performed routinely and revealed concurrent DVT in 31.6% of IPE patients and 42.1% of SPE patients,19 higher than reported previously. Among inpatients diagnosed with IPE, significantly more had concurrent DVT compared with patients with SPE (25% vs 15.7%, p = 0.0333).6

Cancer patients, in particular, may have asymptomatic VTE involving the splanchnic vessels, central line-associated VTE, and lower-extremity DVT.17 Most cancer staging scans, typically the source of the IPE diagnosis, will include the abdominal vessels and the jugular and subclavian veins, although contrast exposure in these vessels may not be timed appropriately to visualize VTE. Lower-extremity duplex ultrasonography provides a noninvasive way to capture most of the remaining veins of interest. However, it should be noted that the sensitivity of ultrasonography among asymptomatic inpatients at moderate risk for VTE is as low as 60% for proximal DVT and only 28.6% for distal DVT.20 However, with an ultrasound positive for DVT in the setting of IPE, the practitioner can recommend anticoagulation with greater confidence.

Consideration 4: does the patient have VTE risk factors, especially reversible ones, or comorbid conditions that influence their risk of clotting or bleeding?

The postoperative state may be an important and reversible risk factor for IPE. Among mechanically ventilated lung transplant recipients, IPE accounts for respiratory deterioration in ∼20% of patients who decompensate,21 and as many as 27% have PE at autopsy.22 Recent surgery is a significant risk factor for IPE among cancer patients.14 Regardless of the presence of symptoms, proximal IPE should be treated with systemic anticoagulation. However, surgery is a reversible risk and is associated with the lowest long-term risk of recurrence.8 Therefore, as with symptomatic postoperative PE, these can be treated with a limited duration of anticoagulation (3-6 months). Options for treatment after curative cancer surgery include low–molecular–weight heparin (LMWH) with transition to an oral vitamin K antagonist, one of the new direct oral anticoagulants, or LMWH alone, which is the treatment of choice for patients with active cancer.8,23 However, it is not clear whether IPE identified after cancer surgery has the same low risk of recurrence if the cancer is still active. For example, a patient with a renal mass excised in the setting of metastatic renal cell carcinoma may remain hypercoagulable as long as the cancer is still active. In general, if IPE occurs in the setting of an active malignancy, consideration should be given to indefinite anticoagulation. A study in which cancer patients with IPE were compared with cancer patients with SPE demonstrated that 20% of recurrent VTE in both groups occurred in patients in whom anticoagulation was held or stopped in the presence of ongoing active malignancy.24 There are no definitive guidelines regarding duration of anticoagulation in such cases, but consideration of the risk/benefit ratio of longer-term anticoagulation should be undertaken periodically.17 Bleeding risk, in particular, must be evaluated, and a predictive model is available to assist in this evaluation for patients treated with warfarin, although its utility may be limited to the initial treatment period.25 Cancer patients treated with dalteparin for 12 months have less frequent major bleeding after the first month of anticoagulation and significantly less bleeding after month 6, whereas breakthrough VTE was higher in the last 6 months as well.26 The role of direct oral anticoagulants in cancer patients with VTE is being explored, but these drugs are not yet recommended routinely for cancer-associated VTE.23

Conclusion

IPE is an important clinical diagnosis and is generally clinically relevant with a majority of patients demonstrating signs and/or symptoms of PE. IPE, especially when symptomatic, is associated with a poor prognosis among cancer patients compared with cancer patients without PE. Treatment is recommended for a minimum of 3-6 months for patients with proximal IPE. Although data are lacking to support indefinite anticoagulation in these patients, consideration should be given to the presence of ongoing VTE risk factors, such as active malignancy, and weighed against risk of bleeding. Data are conflicting in regard to patients with isolated ISSPE, and some suggest withholding anticoagulation in this group. Identification of a concurrent DVT and/or presence of an active malignancy should prompt reconsideration of treatment with anticoagulation for this group, although a limited duration such as 3-6 months may be appropriate.

Correspondence

Casey O'Connell, MD, Norris Comprehensive Cancer Center, 1441 Eastlake Avenue, NOR 3460, Los Angeles, CA 90033; Phone: 323-865-3950; Fax: 323-865-0060; email: coconnel@usc.edu.

References

Competing Interests

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The author is on the Board of Directors or an advisory committee for Incyte Corporation and Portola and has been affiliated with the Speakers Bureau for Celgene.

Author notes

Off-label drug use: None disclosed.