Learning Objective

To understand the impact of early integration of palliative care in the care of patients with advanced cancer

Clinical vignette

A 26-year-old man has relapsed acute lymphoblastic leukemia following a bone marrow transplant. His goals are to continue to pursue cure-directed chemotherapy. He suffers from lower back pain secondary to his cancer and vincristine-induced peripheral neuropathy, but has no other symptoms. Is this an appropriate time to consult a palliative care team?

Discussion

Global cancer rates are increasing, and the need for comprehensive care for patients with cancer and for their families is significant.1 The WHO defines palliative care (PC) as “an approach that improves the quality-of-life (QOL) of patients and their families facing the problems associated with life-threatening illness, through the prevention and relief of suffering by means of an early identification and impeccable assessment and treatment of pain and other problems, physical, psychosocial, and spiritual.”2 As affirmed by the WHO, PC is applicable early in the course of any illness, in conjunction with life-prolonging therapies, such as chemotherapy or radiation.2 The American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO), the Institute of Medicine (IOM), the Oncology Nursing Society (ONS), and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) recommend integrating PC early in the course of illness for patients with cancer.1,3-5 We completed a systematic review to evaluate the impact of integrating PC in the care of patients with cancer, and to evaluate ongoing barriers preventing oncology programs from following consensus guidelines.

We conducted a Medline search using the terms “palliative,” “care,” “oncology,” “cancer,” and “integration.” The search yielded 157 unique articles. Results were limited to articles published since 2010, yielding 98 unique articles, of which 76 were excluded after title and abstract review. References of review articles and citations in the remaining 22 articles, in addition to discussion with colleagues, yielded an additional 9 manuscripts. Eleven studies focusing on oncology provider perceptions of and barriers to PC integration, 1 quality improvement initiative, 1 retrospective chart review, and 1 qualitative study of caregiver experiences were excluded due to lack of information regarding integrating PC into oncology practice. Four review articles,6-9 3 consensus guideline or group recommendation statements,1,3,4 3 randomized controlled trials10-12 and 3 subanalyses of 2 of these,13-15 1 mixed methods study,16 1 prospective cohort study,17 1 cross-sectional study,18 and 1 retrospective cross sectional19 study comprised the 17 included articles.

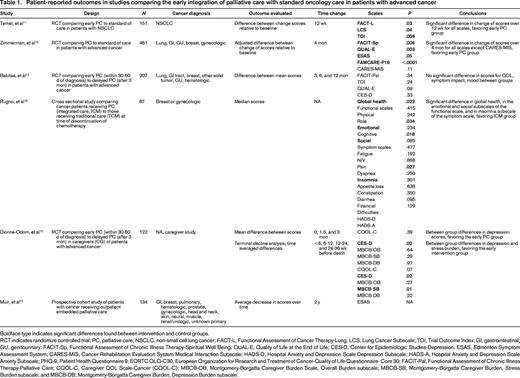

Six studies, including 3 randomized controlled trials, 1 cross sectional study, and 1 prospective cohort study, utilized patient-reported measures of symptom assessment, depression, and/or quality-of-life to compare outcomes in patients with advanced cancer, or their caregivers, who received early integration of PC to those who received standard or traditional oncology care (Table 1).10-12,15,17,18

Patient-reported outcomes in studies comparing the early integration of palliative care with standard oncology care in patients with advanced cancer

Boldface type indicates significant differences found between intervention and control groups.

RCT indicates randomize controlled trial; PC, palliative care; NSCLC, non-small cell lung cancer; FACT-L, Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Lung, LCS, Lung Cancer Subscale; TOI, Trial Outcome Index; GI, gastrointestinal; GU, genitourinary; FACIT-Sp, Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Spiritual Well Being; QUAL-E, Quality of Life at the End of Life; CES-D, Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression; ESAS, Edmonton Symptom Assessment System; CARES-MIS, Cancer Rehabilitation Evaluation System Medical Interaction Subscale; HADS-D, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale Depression Subscale; HADS-A, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale Anxiety Subscale; PHQ-9, Patient Health Questionnaire 9; EORTC QLQ-C30, European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer-Quality of Life Questionnaire- Core 30; FACIT-Pal, Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Palliative Care; CQOL-C, Caregiver QOL Scale-Cancer (CQOL-C); MBCB-OB, Montgomery-Borgatta Caregiver Burden Scale, Overall Burden subscale; MBCB-SB, Montgomery-Borgatta Caregiver Burden, Stress Burden subscale; and MBCB-DB; Montgomery-Borgatta Caregiver Burden, Depression Burden subscale.

Temel et al found that patients with NSCLC randomized to an early outpatient PC intervention had significantly better QoL scores than those randomized to standard care after 12 weeks, via the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Lung (FACT-L) scale, the Lung Cancer Subscale (LCS) of the FACT-L and the Trial Outcome Index (TOI), which is the sum of the scores on the LCS an the physical well being and functional well being subscales of the FACT-L.11 In addition, in this study the proportion of patients with depression at 12 weeks as measured by the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) and Patient Health Questionnaire 9 (PHQ-9) was significantly lower in the PC group than the standard of care group, though the proportion receiving new prescriptions for antidepressant drugs was similar in both groups.11 Subsequent analyses of data from this study demonstrate that the early palliative care intervention largely consisted of: (1) symptom management, (2) assistance with coping, (3) and facilitating communication between the patient and the oncologist.20

Zimmermann et al found that patients with advanced cancer who were randomized to early PC had significantly different quality-of-life (QoL) scores than those randomized to standard oncology care at 4 months, via the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Spiritual Well Being (FACIT-Sp) scale, the Quality of Life at the End of Life (QUAL-E) scale, the Edmonton Symptom Assessment System (ESAS), and a satisfaction with care (FAMCARE-P16) scale, but not on the Cancer Rehabilitation Evaluation System Medical Interaction Subscale (CARES-MIS).10

Most recently, Bakitas et al reported on results of the ENABLE (Educate, Nurture, Advise, Before Life Ends) III trial, which randomized patients with advanced cancer to early intervention of PC, defined as initiating PC within 30-60 days of diagnosis, versus delayed PC, defined as initiating PC after 3 months.12 Study outcomes included patient-reported QOL, assessed by the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Palliative Care (FACIT-Pal) survey, symptom impact, assessed by the QUAL-E symptom impact subscale, and mood, assessed by the Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression (CES-D) scale. No significant difference in mean scores between the groups was found on any scale at 3 months, 6 months, or 12 months from enrollment, however overall survival was significantly longer in the early palliative care arm. The ENABLE III trial also randomized caregivers of patients with advanced cancer to early versus delayed PC intervention.15 Caregiver outcomes included quality-of-life assessed by the Caregiver QOL Scale-Cancer (CQOL-C), depression as measured by the CES-D, and caregiver burden assessed by the Montgomery-Borgatta Caregiver Burden (MBCB) Scale. There were significantly better median depression scores in the early PC group compared with the delayed PC group.15 Additionally, a terminal decline analysis found significantly better scores in depression and the stress burden subscale of the MBCB scale in caregivers randomized to the early PC group, when compared to the delayed PC group.15

Rugno et al evaluated patients with advanced breast or gynecologic cancer at the time of discontinuation of chemotherapy, and found that those women who had received PC under an integrated care model (ICM) exhibited higher mean scores for global health, emotional functioning and social functioning on the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer-Quality of Life Questionnaire-Core 30 (EORTC QLQ-C30) than those who received standard oncology care under a traditional care model (TCM).18 There was no significant difference between women in the ICM and TCM groups in other functional subscales of the EORTC QLQ-C30. Women in the ICM group exhibited significantly better scores for insomnia than those in the TCM group, but there was no significant difference in scores for other symptoms.18 Further, there was no significant difference between the 2 groups in anxiety and depression scores on the HADS.18

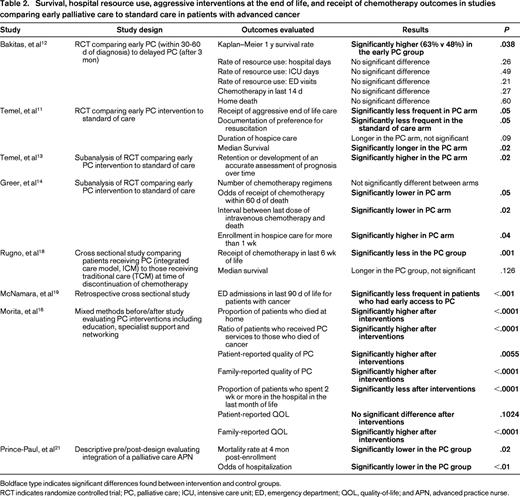

Eight studies reported other outcomes for integrating PC into the care of patients with cancer (Table 2).11-14,16,18,19,21 Three studies documented significantly longer survival for patients exposed to earlier PC interventions when compared to those who received standard oncology care; a fourth study also found longer survival for the PC group, though the difference was not significant.11,12,18,21 One study documented significantly decreased receipt of aggressive interventions at EOL and significantly longer duration of hospice care and for patients randomized to earlier PC interventions.11 Two studies found a relationship between early PC intervention and decreased likelihood of receipt of chemotherapy within days and weeks of death, although one did not.12,14,18 Similarly, whereas 1 study documented decreased likelihood of ED admissions in the last 90 days of life for patients exposed to PC and another documented decreased hospitalization rates for PC patients, a third did not find a difference in hospital days, ICU days, or ED visits in patients exposed to PC earlier.12,19,21

Survival, hospital resource use, aggressive interventions at the end of life, and receipt of chemotherapy outcomes in studies comparing early palliative care to standard care in patients with advanced cancer

Boldface type indicates significant differences found between intervention and control groups.

RCT indicates randomize controlled trial; PC, palliative care; ICU, intensive care unit; ED, emergency department; QOL, quality-of-life; and APN, advanced practice nurse.

Multiple barriers to integration of PC have been described. Unclear pathways and triggers for referral, fragmentation of services, confusion regarding the provider role, belief that palliative care represents hospice or EOL care, budget, or financial constraints,22,23 workforce shortages, and concerns about patient readiness have all been cited as avenues for improvement in integrating PC into the care of patients with cancer.24-31 To address some of these barriers, some groups have developed malignancy-specific treatment guidelines or “standard operating procedures” to identify a disease-specific point in each disease trajectory to initiate PC.32 To our knowledge, no such triggers have been identified in the hematologic malignancies or pediatric oncology settings.

Conclusions

Early integration of PC into the care of patients with advanced cancer has demonstrated improvements in patient quality-of-life, mood, symptom burden and EOL outcomes, and in caregiver burden and psychological outcomes, as well as resource utilization. (Strong recommendation; high-quality evidence.) To our knowledge, no studies have demonstrated patient harm or increased cost due to the involvement of a PC team. Physicians caring for patients with advanced cancer and/or those with a significant symptom burden should consider referring patients to PC; this should include those with hematologic malignancies or pediatric cancers. More research is needed to explicitly describe and define the unique palliative care needs of patients with hematologic malignancies and pediatric cancers, so that interventions may be developed for these populations.

Correspondence

Rachel Thienprayoon, Department of Anesthesia, Division of Pain and Palliative Care, Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center, 3333 Burnet Ave, ML-2001, Cincinnati, OH 45229-3039; Phone: 513-803-4687; Fax: 513-636-2920; e-mail: rachel.thienprayoon@cchmc.org.

References

Competing Interests

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Author notes

Off-label drug use: None disclosed.