Abstract

Histologic transformation (HT) is a frequent event in the clinical course of patients with indolent lymphoma. Most of the available data in the literature comes from studies on transformation of follicular lymphoma (FL), as this is the most common indolent lymphoma; however, HT is also well documented following small lymphocytic lymphoma/chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (SLL/CLL), lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma (LPL), or marginal zone lymphoma (MZL), amongst other types of lymphoma, albeit most of the studies on transformation in these subtypes are case reports or short series. The outcome of patients with HT has traditionally been considered dismal with a median overall survival (OS) of around 1 year in most of the published studies. This prompted many authors to include stem cell transplant (SCT) as part of the treatment strategy for young and fit patients with HT. However, recent articles suggest that the outcome of patients with transformed lymphoma might be improving, questioning the need for such intensive therapies. The management of patients with HT is challenged by the heterogeneity of the population in terms of previous number and type of therapy lines and from their exclusion from prospective clinical trials. This review will examine whether the advent of new therapies has impacted on the prognosis of HT and on current treatment strategies.

Learning Objectives

HT remains a significant challenge in the management of patients with indolent lymphoma

Patients who are chemotherapy-naïve at the time of HT have a very good outcome when treated with R-CHOP

SCT should be considered in patients who present HT after one or more prior lines of chemotherapy

How frequent is HT?

The incidence of histologic transformation (HT) in patients diagnosed with follicular lymphoma (FL) varies enormously amongst different series, depending on the definition of HT. The purest and strictest definition requires a biopsy for the diagnosis of transformation to an aggressive lymphoma. In the majority of the cases, FL transforms to diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), although transformation to Burkitt lymphoma or lymphoblastic lymphoma is also reported. However, many studies, especially in the past, have included HT based on cytologic samples.1,2 On the other extreme, several series include cases of HT diagnosed following clinical criteria.3 The histologic changes seen in patients with HT are accompanied in the great majority of cases by a change in the clinical features of the disease towards a more aggressive course. This well recognized fact led to Al-Tourah et al to publish in 2008 clinical criteria to define transformation.2 This included a rapid discordant lymphadenopathy growth, unusual sites of extra-nodal involvement, a sudden rise in the LDH level, hypercalcemia, or presence of new B-symptoms. Thus, depending on whether the series include cases of transformation based on histologic, cytologic, or clinical criteria, the risk of HT at 10 years in patients with FL varies from 15% to 31%.1-4

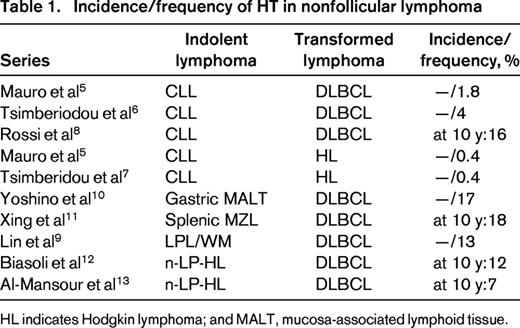

In contrast, the diagnosis of transformation to DLBCL in other types of indolent lymphoma is in general, more straightforward, as the possibility of cytologic progression being diagnosed as HT does not exist. HT has been reported in patients with small lymphocytic lymphoma/chronic lymphocytic leukemia (SLL/CLL),5-8 lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma (LPL),9 marginal zone lymphoma (MZL),10,11 or nodular lymphocyte predominant Hodgkin lymphoma (nLP-HL).12,13 The data available on the frequency of HT in patients with lymphomas other than FL comes mostly from case reports or short series and varies from <1% to 13% with a 10 year risk of transformation of 7%-16% (Table 1). There has been some suggestion that the incidence of HT has decreased in the so-called “rituximab-era” with a study from Switzerland reporting that diagnosis of FL after 1990 is associated on multivariate analysis with a lower incidence of HT.14

Outcome of patients with HT: improvement over time

Outcome of patients with HT in old series

Historically, the outcome of patients with HT has been considered dismal, with a median overall survival (OS) of around 1 year in the majority of the series.1,2,4 Several studies have demonstrated that the outcome of patients who present HT is significantly worse than that in patients without transformation.2,4 However, there seems to be differences in the outcome of patients with transformed non-FL depending on the histologic subtype of the indolent lymphoma. Thus, whereas the outcome of patients with Richter syndrome (that is, histologic transformation of CLL/SLL to DLBCL) or of those with CLL/SLL transforming to Hodgkin lymphoma (HL) is very poor with a median OS that ranges from 8 to 16 months,6-8 the outcome of patients with n-LP-HL who transform to DLBCL seems to be significantly better. Thus, the largest series on HT in patients with nLP-HL reported a 10 year OS of 60%,12 and the study from the British Columbia Cancer Agency (BCCA) showed similar results (10 year OS: 62%).13 Not surprisingly, localized stage at the time of transformation and not having received chemotherapy has been associated in old series (including mostly transformed FL) with a better outcome after transformation.15

Given the poor prognosis of patients after HT efforts were made at elucidating whether initial management has an impact on the subsequent risk of transformation. Unfortunately, the risk of HT has rarely been included as an end-point in prospective clinical trials, so most of the information available comes from retrospective studies. There are contradictory data with respect to the impact of expectant management on the risk of transformation. A large retrospective series reported a significantly higher risk of HT amongst patients with FL initially managed expectantly at diagnosis,4 but this data was not confirmed in another retrospective study.2 Unfortunately, the data coming from randomized controlled trials analyzing the role of expectant management in patients with FL is inconclusive, with no information on the risk of HT, such as in the British National Lymphoma Investigation (BNLI) study,16 or with contradictory results. The trial run by Groupe d'Etude des Lymphomes de l'Adult (GELA) showed that expectant management was not associated with an increased risk of HT,17 whereas another old study comparing a relatively intensive chemotherapy regimen with expectant management suggested that the latter was associated with a higher risk of HT18 ; however, the details on HT in this article are limited making difficult to draw any conclusions. The most recent trial comparing a watch and wait approach with rituximab did not show any differences in the risk of transformation.19 Along the same lines, the role of anthracyclines as part of the initial therapy to reduce the risk of HT is controversial. The BCCA series2 compared in a nonrandomized fashion the risk of HT in patients treated in 2 sequential clinical trials, and showed that those treated in the study including anthracyclines had a significantly lower risk of HT. However, although the 2 trials shared the same inclusion criteria this is, nonetheless, another retrospective study. Only one old randomized trial analyzed the risk of HT according to the inclusion or not of anthracyclines as part of the induction regimen, and did not find any protective effect against HT in patients who received the anthracycline-containing regimen.20 Finally, although some case reports had suggested that patients with CLL treated with fludarabine had a higher risk of Richter syndrome, 2 randomized studies failed to demonstrate that fludarabine-containing regimens increase the risk of HT in this population.21,22 Thus, there is no evidence-based data to support that the risk of HT can be reduced by the choice of the initial treatment, so the only option left to improve the outcome of patients with HT is to develop better therapeutic strategies at the time of transformation.

Unfortunately, HT is a frequent exclusion criteria from many prospective clinical trials, so decisions on the management of patients with HT are often based on extrapolation of data from prospective trials in DLBCL, as this is the commonest “transformed lymphoma”, or from retrospective series, with little evidence-based data. Given the poor prognosis of patients with HT in the pre-rituximab series, many authors supported the use of high-dose therapy with autologous stem cell rescue (HDT-ASCR) in patients with HT responding to salvage therapy. Several studies published in the 1990s and early 2000s reported 5 year OS after HDT-ASCR ranging from 37% to 81%.23-26 A registry study demonstrated that the outcome of patients who had HDT-ASCR for transformed lymphoma was similar to that of patients who received HDT-ASCR for an indolent lymphoma or for an aggressive lymphoma.26 Undoubtedly, these results are much better than those reported in general series of patients with transformed lymphoma, however, it is clear that retrospective series on HDT-ASCR are inherently biased toward a good risk population, as patients need to achieve a response to proceed to HDT-ASCR and response to treatment has, not surprisingly, been associated with a better outcome in patients with HT.1,15

Has the outcome of patients with HT improved in recent years?

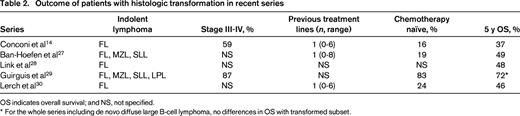

Several studies published in the last 5 years suggest that the outcome of patients with HT has significantly improved in the so-called “rituximab era”. Thus, 5 year OS ranges from 46% to 72% in “general” series of HT, that is, series not selected for transplanted patients (Table 2).14,27-30 With the exception of the Guirguis et al29 series (in which patients with transformed lymphoma were excluded if they had been treated with R-CHOP prior to HT), in most of the series the majority of the patients have received chemotherapy prior to the diagnosis of HT and have advanced stage at the time of transformation (Table 2), so the better outcome in recent years cannot be attributed to an earlier identification of HT leading to a better-risk population.

Outcome of patients with histologic transformation in recent series

OS indicates overall survival; and NS, not specified.

* For the whole series including de novo diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, no differences in OS with transformed subset.

As mentioned earlier, in the majority of the cases the transformed lymphoma has the pathologic features of DLBCL. Moreover, Davies et al demonstrated in a paired-samples study that the gene expression profile of samples of transformed FL resembled that of germinal center DLBCL, with significant differences compared with the original FL.31 Hence, the obvious conclusion is that the best treatment option for patients with transformed lymphoma (to DLBCL) should be the best known treatment for DLBCL. Indeed, several series have demonstrated that the outcome of patients with HT who had not received R-CHOP prior to HT and received this regimen at transformation is comparable to that of patients with de novo DLBCL treated with R-CHOP.28,29 Along the same lines, amongst patients whose HT treatment did not include stem cell transplantation (SCT) in the National Cancer Comprehensive Network (NCCN) study, those who were anthracycline-naïve had a better outcome than patients previously treated with anthracyclines.27 An analogous situation is that of patients diagnosed with composite/discordant lymphoma, that is, with transformed lymphoma at diagnosis without a previous phase of indolent lymphoma. Madsen et al reported that although the inclusion of HDT-ASCR as part of the management of HT was associated with a better outcome in terms of progression-free survival (PFS), this strategy did not result in a better outcome for patients with composite/discordant lymphoma.32 However, one has to bear in mind that HT rarely happens as the first event in the course of the disease and most of the patients are previously treated at the time of HT, which clearly influences the treatment at transformation. This leads to the question of whether the choice of initial treatment/s has an impact on the response at the time of HT. In this sense, one of the most relevant questions presently is whether prior treatment with rituximab has a deleterious effect on the outcome after transformation. Lerch et al demonstrated that having received rituximab before the diagnosis of HT was not associated with a worse outcome in patients with transformed lymphoma30 ; this is in contrast with the situation in patients with relapsed DLBCL who have a significantly worse prognosis at progression, if they have previously received rituximab. Similarly, 2 studies showed that prior rituximab did not result in a worse outcome in patients who received HDT-ASCR for HT.27,32 Patients who have previously received CHOP (with or without rituximab) are frequently treated with second-line regimens for DLBCL. Given the heterogeneity of the series in terms of the number and type of previous treatment lines, it is difficult to draw any conclusions about any specific regimen.

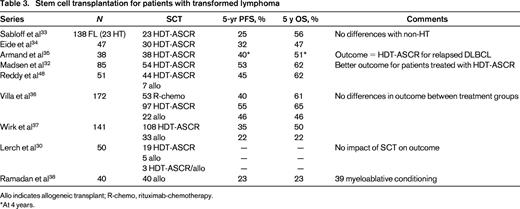

Young and fit patients responding to therapy for HT are often offered consolidation with HDT-ASCR. The most recent studies in this field show that patients that present with HT after prior treatment still benefit from HDT-ASCR, with a 5 year OS ranging from 47% to 62% (Table 3).32-37 Some of these studies suggest that patients who received HDT-ASCR present a better outcome than those not transplanted,32,36 although other studies do not detect any impact on prognosis of HDT-ASCR.30 Allogeneic transplants have also been incorporated into the management of patients with HT, although much less frequently than HDT-ASCR, and they often result in a significantly high transplant-related mortality (TRM), especially when myeloablative conditioning regimens are used.38

Stem cell transplantation for patients with transformed lymphoma

Allo indicates allogeneic transplant; R-chemo, rituximab-chemotherapy.

*At 4 years.

Much less data is available on the management of patients with transformed non-FL, but in general, the choice of treatment is simpler, as there is much less overlap of treatment options between the indolent and the transformed lymphoma. In general, patients are treated with standard regimens for the transformed lymphoma, and there is also a tendency to consolidate the response with SCT in young and fit patients responding to the salvage regimen. Many studies include a variety of indolent lymphomas, FL being the most frequent subtype, with only a few reporting specifically the outcome of patients with non-FL transformation. Thus, Cwynarski et al published the data of the Lymphoma Working Party of the European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation (EBMT) on SCT for Richter syndrome and reported a 3 year relapse-free survival (RFS) and OS of 45% and 59%, respectively, for 34 patients who received HDT-ASCR for Richter syndrome; the corresponding figures for 25 patients who received an allogeneic transplant were 27 and 36%, and the 3 year TRM was 26%.39 However, it is important to point out that a significant proportion of patients with Richter syndrome do not achieve a response good enough to proceed to SCT. Villa et al collected data on 34 patients with transformed non-FL who received an SCT (22 HDT-ASCR, 12 allogeneic transplant) and showed no differences in outcome according to the type of transplant, and more importantly, no differences in outcome when compared with a control group of patients with FL.40

Treatment at the time of HT

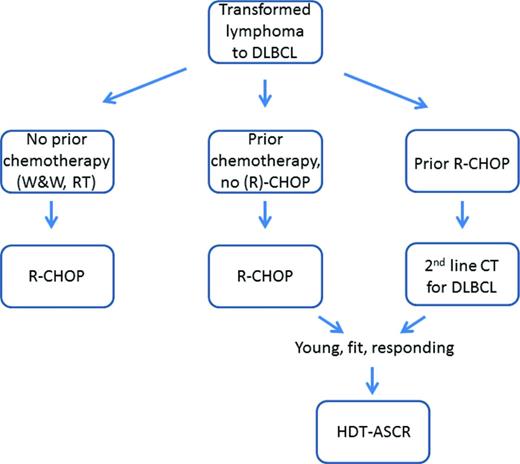

Following on from the premise that patients with transformation to DLBCL should be treated with the best treatment option for this type of lymphoma, and from the data presented above, patients who present with HT not having received R-CHOP, should receive this regimen. Given the excellent results with R-CHOP in chemotherapy-naïve patients (ie, those previously managed expectantly or treated only with radiotherapy), the need for HDT-ASCR has been brought into question. In contrast, consolidation with HDT-ASCR should be considered in patients treated with R-CHOP at HT following one or more previous chemotherapy lines. For the subset of patients who had received R-CHOP prior to HT, second line chemotherapy for DLBCL should be given. There is not any clear evidence of superiority of one salvage regimen over the others, and again, consolidation with HDT-ASCR should be considered in those young and fit who respond to the salvage therapy (Figure 1).

How I treat patients with transformed lymphoma: proposed treatment algorithm. W&W indicates watch and wait; RT, radiotherapy; and CT, chemotherapy.

How I treat patients with transformed lymphoma: proposed treatment algorithm. W&W indicates watch and wait; RT, radiotherapy; and CT, chemotherapy.

Is there any role for maintenance with rituximab?

Given the excellent effect of maintenance with rituximab in the outcome of patients with FL, it is reasonable to question whether this strategy is applicable with the same results in patients with FL who have transformed to DLBCL. This population was, obviously, excluded from clinical trials testing the efficacy of maintenance with rituximab in patients with FL, as were patients with grade 3/3b in some of the studies. The role of maintenance rituximab in patients with DBCL has also been studied is a few prospective trials. Habermann et al demonstrated that the addition of maintenance with rituximab did not improve the outcome of patients with DLBCL treated with R-CHOP.41 In addition, 2 studies analyzed the role of maintenance rituximab following HDT-ASCR in patients with DLBCL and showed that maintenance with rituximab was not associated with a better outcome,42,43 contrasting with the results observed in a similar randomized study in patients with FL.44 Of note, in the GELA trial patients with “initial transformation” were included in the study. Nevertheless, some authors advocate the use of maintenance rituximab in patients with HT to treat the “underlying indolent lymphoma”.

Novel therapies: the future?

As mentioned previously, patients with transformed lymphoma are often excluded from prospective clinical trials, so information on the efficacy of new drugs for HT is scarce. Amongst “novel” drugs that are not so new anymore, lenalidomide demonstrated significant activity in a phase II study for patients with relapse/refractory aggressive lymphoma.45 Likewise, promising results were published in patients with HT treated with radio-immunotherapy.46 More recently a plethora of new drugs targeting crucial pathways in B-cell lymphomas has been developed, including BCR inhibitors, PI3κ inhibitors, immune checkpoint inhibitors and Bcl-2 antagonists. Amongst those, the PD-1 inhibitor pidilizumab has recently shown activity in a phase II study that included 20% of the patients with HT, although the results were not presented separately for this subset of patients.47

Conclusion

In spite of the undoubted improvement in the outcome of patients with HT, this is still a significant event in the course of the disease of patients with indolent lymphoma. There is no clear evidence that the initial management has an impact on the subsequent risk of transformation, so at present we do not have the tools to reduce its incidence. The fact that the risk of HT is rarely an end-point in prospective studies in indolent lymphoma constitutes a significant obstacle for advances in the field, emphasizing the need for the inclusion of risk of HT as an end-point in clinical trials. Along the same lines, patients with HT are often excluded from prospective trials for both indolent and aggressive histologies. Decisions on the management of HT are therefore based on weak evidence from retrospective studies or from the extrapolation of information obtained from studies in patients with DLBCL. Hence, the improvement in the outcome of patients with HT has not come from a better understanding of the pathogenesis of HT or from data obtained from trials performed in patients with HT, but from the availability of a better treatment for patients with DLBCL. This is a consequence of the incorporation of rituximab, and possibly, of a switch in recent years from anthracycline-containing regimens as first-line therapy for indolent lymphomas to other options, such as bendamustine.

Correspondence

Silvia Montoto, Department of Haemato-oncology, St Bartholomew's Hospital, KGV 5th Fl, West Smithfield, EC1A 7BE London, UK; Phone: +44 203 4656070; Fax: +44 872 352 4277; e-mail: s.montoto@qmul.ac.uk.

References

Competing Interests

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The author has received honoraria from Roche.

Author notes

Off-label drug use: None disclosed.