Abstract

Although rituximab plus cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (R-CHOP) is the standard treatment for patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), ∼30% to 50% of patients are not cured by this treatment, depending on disease stage or prognostic index. Among patients for whom R-CHOP therapy fails, 20% suffer from primary refractory disease (progress during or right after treatment) whereas 30% relapse after achieving complete remission (CR). Currently, there is no good definition enabling us to identify these 2 groups upon diagnosis. Most of the refractory patients exhibit double-hit lymphoma (MYC-BCL2 rearrangement) or double-protein-expression lymphoma (MYC-BCL2 hyperexpression) which have a more aggressive clinical picture. New strategies are currently being explored to obtain better CR rates and fewer relapses. Although young relapsing patients are treated with high-dose therapy followed by autologous transplant, there is an unmet need for better salvage regimens in this setting. To prevent relapse, maintenance therapy with immunomodulatory agents such as lenalidomide is currently undergoing investigation. New drugs will most likely be introduced over the next few years and will probably be different for relapsing and refractory patients.

Learning Objectives

To be able to determine at diagnosis which DLBCL patients will likely experience treatment failure with R-CHOP

To understand the mechanisms that underlie resistance to standard treatments

To be able to assess the new proposed drugs, along with their efficacy for specific lymphoma populations such as those with double-hit lymphoma or double-protein-expression lymphoma

To learn more about potential solutions for refractory or relapsing patients

Introduction

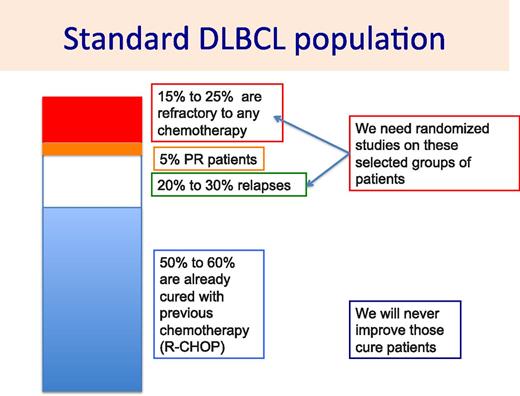

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is the most common lymphoma, representing 25% of all lymphoproliferative disorders.1 Despite its aggressive disease course, ∼50% to 70% of patients may be cured by current standard of care consisting of rituximab plus cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (R-CHOP) chemotherapy.2 Nevertheless, R-CHOP is found to be inadequate in 30% to 40% of patients. For these patients, different processes may account for their lack of response to R-CHOP. Death related to R-CHOP toxicities, although it is a rare event in young patients, may be observed in 5% of patients older than age 70 years. This treatment-related mortality is usually associated with an absence of response. R-CHOP failures are principally due to either primary refractoriness or relapse after reaching a complete response (CR) (Figure 1). A few more patients (<5%) do not achieve CR but only partial response (PR) with either persisting lymphoma cells on biopsy or persisting active tumor volume on positron emission tomography (PET) scan. These different settings are related to different mechanisms of resistance to chemotherapy, requiring appropriate solutions to increase the cure rates.

In this review, HIV-related lymphomas, posttransplant lymphomas, central nervous system lymphomas, and transformed lymphomas will not be covered, although comments pertaining to refractory and relapsing lymphomas may be applied to these particular entities.

Refractoriness to R-CHOP

Although several mechanisms of resistance may account for refractoriness to R-CHOP, the majority of DLBCL patients present a double rearrangement of MYC and BCL2 genes called double-hit lymphoma (DHL). Indeed, DHLs are defined as a chromosomal breakpoint, affecting the MYC/8q24 locus in combination with another recurrent breakpoint, usually BCL2 (t(14;18)(q32;q21)), although BCL6/MYC-positive DHLs or BCL2/BCL6/MYC-positive triple-hit lymphomas (THLs) may also be observed. All studies that focused on DHLs or THLs concluded that the patients’ outcomes were poor, with R-CHOP probably not being the best therapeutic option. These rearrangements can be observed with fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) analysis.3,4

Recently, immunohistochemistry has allowed patients with high expression of MYC and BCL2 proteins to be identified, but no gene rearrangements show up in FISH analyses. In addition, patients who have double-protein expression lymphoma (DPL) exhibit a poorer outcome compared with patients who do not have DHL or DPL, although they have a slightly better outcome than DHL patients.3,5 Because of the risk of poor outcome, screening for DHL by FISH analysis (rearrangement) or DPL by immunohistochemistry (overexpression) should be mandatory for every DLBCL patient.

In several studies, MYC rearrangement, hyperexpression without BCL2 rearrangement, or BCL2 hyperexpression have been associated with poor outcome, whereas in other studies, the authors reported that no difference was seen compared with patients without MYC abnormality.6,7 Patients with MYC mutations may experience either a better or poorer outcome, depending on the type of mutation.8 This may explain the contradictory reports found in the literature. Patients with MYC overexpression, particularly the Myc-N11S variant, have a better outcome than patients with other MYC mutations.8 BCL2 rearrangement alone is not associated with a poorer outcome. However, BCL2 hyperexpression alone does predict a shorter progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) in DLBCL patients, this difference being more relevant in germinal center B-cell lymphoma than activated B-cell lymphoma subtypes.9

Several other exploratory studies have retrospectively investigated multiple parameters that may be associated with low CR rates, shorter event-free survival (EFS), shorter PFS, or shorter OS. Table 1 lists clinical, radiologic, genetic, and antigenic parameters that have been associated with outcome over the last 5 years. Most of the studies included only a small number of patients, and although several studies correlated their findings with prognostic indices or cell of origin, none of them sought correlations between outcome and DHL, THL, or DPL subtypes. Therefore, their clinical usefulness and impact on the physician’s decision-making process regarding new treatment strategies in DLBCL patients seems to be low. Neither the International Prognostic Index nor its modified forms (eg, the Revised International Prognostic Index) allow these refractory patients to be recognized. Given that cell of origin has not been associated with either DHL or DPL, it does not seem to be a useful parameter for recognizing these patients either.

Parameters associated with outcome in DLBCL patients treated with R-CHOP or R-CHOP-like regimens

| Antigens . | Pathways . | Oncogenes . | Imaging . | Others . | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | PFS/OS/EFS . | Reference . | . | PFS/OS/EFS . | Reference . | . | PFS/OS/EFS . | Reference . | . | PFS/OS/EFS . | Reference . | . | PFS/OS/EFS . | Reference . |

| HLA-G polymorphism | Short OS (for poor-risk patient) | 38 | High p-AKT expression | Shorter PFS and OS | 39 | Double-hit lymphoma | 3 | PET at end of treatment; 7%-20% relapse rate | 40 | CD5+ | PFS, 40%; OS, 65% | 41 | ||

| CXCR4 expression, particularly if associated with BCL2 translocation | Shorter PFS in GCB | 42 | Older age and male sex associated with JUN and CYCS signaling | Shorter PFS and OS | 43 | TP53 mutation plus MIR34A methylation, rare (6%) but very aggressive | 44 | Tumor necrosis at diagnosis | High correlation with PFS and OS | 45 | Anemia and high CRP at diagnosis | Shorter PFS and OS | 46 | |

| Ki-67 >80% | Shorter PFS and OS | 47 | 11-gene STAT3 activation signature | Shorter OS and EFS | 48 | Isolated MYC abnormalities not associated with outcome | Other studies had shorter PFS and OS | 7 | Interim PET positivity | Shorter PFS, but not in all studies | 49, 50 | High CXCL 10 | Shorter EFS and OS | 51 |

| High serum sIL-2R | Shorter PFS and OS | 52, 53 | High miR-155 expression; R-CHOP failure | 54 | RCOR1 deletion and RCOR1 loss-associated signature | Shorter OS | 55 | ΔSUVmax <83% | Shorter PFS and OS | 56 | Occult BM involvement | Shorter PFS and OS (similar to BM-positive) | 57 | |

| High serum sCD27 | Shorter OS | 58 | CDKN2A loss | Shorter OS | 59 | High expression of BCL2, particularly with low-risk IPI | Shorter PFS and OS | 9 | Sarcopenia on CT scan | Shorter OS | 60 | Low serum albumin level (<35 g/L) | 5-y PFS, 51%; OS 53% | 61 |

| High serum IL-18 | Shorter PFS and OS | 62 | DAPK1 promoter methylation | Shorter OS and DFS | 63 | MYC-Ig gene translocation | Shorter PFS and OS | 64 | High metabolic tumor volume | Shorter OS | 65 | Vitamin D deficiency | Shorter EFS and OS | 66 |

| High VEGFR2 expression | Shorter OS | 67 | High EZH2 expression | Longer OS | 68 | TNFAIP3 and GNA13 mutations | Shorter OS in ABC lymphoma | 69 | Cachexia score | Shorter PFS and OS | 70 | |||

| CD30 positivity | Shorter EFS and OS | 71 | High slug expression | Longer PFS and OS | 72 | Double-protein level expression | Shorter PFS and OS | 73, 74 | Concordant BM involvement | Shorter PFS and OS | 75 | |||

| Low HLA-DR expression | Shorter OS | 76 | High ZEB1 expression | Shorter OS | 72 | Low miR-129-5p expression | Shorter OS | 77 | Abnormal IgMκ:IgMλ ratio | Shorter PFS | 78 | |||

| C1qA A/A allele | Longer OS | 79 | High Trx-1 expression | Shorter OS | 80 | MYC overexpression | Shorter OS | 4 | Stage III or tumor >5 cm; increased local recurrence | 81 | ||||

| MET-RON phenotype | Shorter OS | 82 | TP53 pathway dysregulation | Shorter PFS and OS | 83 | Homozygous STAT3 phenotype | Longer OS | 84 | Worse pretreatment QoL | Shorter OS | 85 | |||

| High survivin expression | Shorter OS | 86 | High miR-34A expression; higher response to doxorubicin | 87 | High BCL2 expression | Shorter PFS and OS | 88 | High neutrophil: lymphocyte ratio | Shorter PFS and OS | 85 | ||||

| Higher PRAME expression | Shorter PFS | 90 | p52/RELB expression | Longer PFS and OS | 91 | MYC and BCL2 copy number aberrations | Shorter PFS and OS | 92 | Low CD4+ TILs | Shorter PFS and OS | 93 | |||

| High β2-microglobulin | Shorter PFS and OS | 94 | Epigenomic heterogeneity; higher early relapses | 12 | High GSTP1 and TOPO2α | Shorter PFS and OS | 95 | Low ALC/AMC ratio | Shorter PFS and OS | 96 | ||||

| High BiP/GRP78 expression | Shorter OS | 97 | High S1PR1 and S1PR1/pSTAT3 expression | Shorter OS | 98 | Loss of SLC22A16 (doxorubicin transporter); higher early relapses | 99 | EBV-positive (high EBER expression) | Shorter PFS and OS | 100 | ||||

| High sTNFR2 | Shorter PFS and OS | 101 | High LincRNA-p21 | Longer PFS and OS | 102 | MLH1 AG/GG genotype; higher early progression | Shorter OS | 103 | Increased TAMs (CD68+ cells) | Longer OS | 104 | |||

| High miR-224 expression | Shorter PFS and OS | 105 | Low GILT expression | Shorter OS | 106 | del(8p23.1) | Shorter OS | 107 | Increased M2 (CD163+ cells) | Shorter PFS and OS | 104 | |||

| REV7 expression | Shorter PFS and OS | 108 | Serum miRNA signature; increased early progression | 109 | p53 deletion or mutations | Shorter PFS | 110 | Immunoblastic morphology | Shorter EFS and OS | 111 | ||||

| Circulating tumor DNA; higher relapse rate | 112 | Low HIP1R expression | Shorter PFS and OS | 113 | FOXP1 expression | Shorter OS | 114 | High CRP level | Shorter PFS and OS | 115 | ||||

| Higher sPD-L1 protein | Shorter OS | 116 | High miR-125b and miR-130a; high risk of failure | 117 | TP53 G/G genotype; high failure rate | 117 | Comorbidity | Shorter OS | 118 | |||||

| High CD59 expression | Shorter PFS and OS | 119 | Increased UCH-L1 in GCB-DLBCL; early relapse | 120 | Wild-type TP53 | Longer OS | 117 | Male sex | Shorter OS | 121 | ||||

| BAFF-R expression; higher CR rate | Longer PFS and OS | 122 | NF-kB mutations such as NFKBIE and NFKBIZ; increased relapses | 14 | STAT6 mutations; increased relapses | 14 | ||||||||

| High sIL-2R; increased early relapse | 53 | |||||||||||||

| Low CD20 expression | Shorter EFS and OS | 123 | ||||||||||||

| Antigens . | Pathways . | Oncogenes . | Imaging . | Others . | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | PFS/OS/EFS . | Reference . | . | PFS/OS/EFS . | Reference . | . | PFS/OS/EFS . | Reference . | . | PFS/OS/EFS . | Reference . | . | PFS/OS/EFS . | Reference . |

| HLA-G polymorphism | Short OS (for poor-risk patient) | 38 | High p-AKT expression | Shorter PFS and OS | 39 | Double-hit lymphoma | 3 | PET at end of treatment; 7%-20% relapse rate | 40 | CD5+ | PFS, 40%; OS, 65% | 41 | ||

| CXCR4 expression, particularly if associated with BCL2 translocation | Shorter PFS in GCB | 42 | Older age and male sex associated with JUN and CYCS signaling | Shorter PFS and OS | 43 | TP53 mutation plus MIR34A methylation, rare (6%) but very aggressive | 44 | Tumor necrosis at diagnosis | High correlation with PFS and OS | 45 | Anemia and high CRP at diagnosis | Shorter PFS and OS | 46 | |

| Ki-67 >80% | Shorter PFS and OS | 47 | 11-gene STAT3 activation signature | Shorter OS and EFS | 48 | Isolated MYC abnormalities not associated with outcome | Other studies had shorter PFS and OS | 7 | Interim PET positivity | Shorter PFS, but not in all studies | 49, 50 | High CXCL 10 | Shorter EFS and OS | 51 |

| High serum sIL-2R | Shorter PFS and OS | 52, 53 | High miR-155 expression; R-CHOP failure | 54 | RCOR1 deletion and RCOR1 loss-associated signature | Shorter OS | 55 | ΔSUVmax <83% | Shorter PFS and OS | 56 | Occult BM involvement | Shorter PFS and OS (similar to BM-positive) | 57 | |

| High serum sCD27 | Shorter OS | 58 | CDKN2A loss | Shorter OS | 59 | High expression of BCL2, particularly with low-risk IPI | Shorter PFS and OS | 9 | Sarcopenia on CT scan | Shorter OS | 60 | Low serum albumin level (<35 g/L) | 5-y PFS, 51%; OS 53% | 61 |

| High serum IL-18 | Shorter PFS and OS | 62 | DAPK1 promoter methylation | Shorter OS and DFS | 63 | MYC-Ig gene translocation | Shorter PFS and OS | 64 | High metabolic tumor volume | Shorter OS | 65 | Vitamin D deficiency | Shorter EFS and OS | 66 |

| High VEGFR2 expression | Shorter OS | 67 | High EZH2 expression | Longer OS | 68 | TNFAIP3 and GNA13 mutations | Shorter OS in ABC lymphoma | 69 | Cachexia score | Shorter PFS and OS | 70 | |||

| CD30 positivity | Shorter EFS and OS | 71 | High slug expression | Longer PFS and OS | 72 | Double-protein level expression | Shorter PFS and OS | 73, 74 | Concordant BM involvement | Shorter PFS and OS | 75 | |||

| Low HLA-DR expression | Shorter OS | 76 | High ZEB1 expression | Shorter OS | 72 | Low miR-129-5p expression | Shorter OS | 77 | Abnormal IgMκ:IgMλ ratio | Shorter PFS | 78 | |||

| C1qA A/A allele | Longer OS | 79 | High Trx-1 expression | Shorter OS | 80 | MYC overexpression | Shorter OS | 4 | Stage III or tumor >5 cm; increased local recurrence | 81 | ||||

| MET-RON phenotype | Shorter OS | 82 | TP53 pathway dysregulation | Shorter PFS and OS | 83 | Homozygous STAT3 phenotype | Longer OS | 84 | Worse pretreatment QoL | Shorter OS | 85 | |||

| High survivin expression | Shorter OS | 86 | High miR-34A expression; higher response to doxorubicin | 87 | High BCL2 expression | Shorter PFS and OS | 88 | High neutrophil: lymphocyte ratio | Shorter PFS and OS | 85 | ||||

| Higher PRAME expression | Shorter PFS | 90 | p52/RELB expression | Longer PFS and OS | 91 | MYC and BCL2 copy number aberrations | Shorter PFS and OS | 92 | Low CD4+ TILs | Shorter PFS and OS | 93 | |||

| High β2-microglobulin | Shorter PFS and OS | 94 | Epigenomic heterogeneity; higher early relapses | 12 | High GSTP1 and TOPO2α | Shorter PFS and OS | 95 | Low ALC/AMC ratio | Shorter PFS and OS | 96 | ||||

| High BiP/GRP78 expression | Shorter OS | 97 | High S1PR1 and S1PR1/pSTAT3 expression | Shorter OS | 98 | Loss of SLC22A16 (doxorubicin transporter); higher early relapses | 99 | EBV-positive (high EBER expression) | Shorter PFS and OS | 100 | ||||

| High sTNFR2 | Shorter PFS and OS | 101 | High LincRNA-p21 | Longer PFS and OS | 102 | MLH1 AG/GG genotype; higher early progression | Shorter OS | 103 | Increased TAMs (CD68+ cells) | Longer OS | 104 | |||

| High miR-224 expression | Shorter PFS and OS | 105 | Low GILT expression | Shorter OS | 106 | del(8p23.1) | Shorter OS | 107 | Increased M2 (CD163+ cells) | Shorter PFS and OS | 104 | |||

| REV7 expression | Shorter PFS and OS | 108 | Serum miRNA signature; increased early progression | 109 | p53 deletion or mutations | Shorter PFS | 110 | Immunoblastic morphology | Shorter EFS and OS | 111 | ||||

| Circulating tumor DNA; higher relapse rate | 112 | Low HIP1R expression | Shorter PFS and OS | 113 | FOXP1 expression | Shorter OS | 114 | High CRP level | Shorter PFS and OS | 115 | ||||

| Higher sPD-L1 protein | Shorter OS | 116 | High miR-125b and miR-130a; high risk of failure | 117 | TP53 G/G genotype; high failure rate | 117 | Comorbidity | Shorter OS | 118 | |||||

| High CD59 expression | Shorter PFS and OS | 119 | Increased UCH-L1 in GCB-DLBCL; early relapse | 120 | Wild-type TP53 | Longer OS | 117 | Male sex | Shorter OS | 121 | ||||

| BAFF-R expression; higher CR rate | Longer PFS and OS | 122 | NF-kB mutations such as NFKBIE and NFKBIZ; increased relapses | 14 | STAT6 mutations; increased relapses | 14 | ||||||||

| High sIL-2R; increased early relapse | 53 | |||||||||||||

| Low CD20 expression | Shorter EFS and OS | 123 | ||||||||||||

The table represents a summary of studies published during the last 5 years.

ABC, activated B cell; BM, bone marrow; CR, complete response; CRP, C-reactive protein; CT, computed tomography; EBV, Epstein-Barr virus; GCB, germinal center B-cell; IL-18, interleukin-18; IPI, International Prognostic Index; Ig, immunoglobulin; miRNA, microRNA; NF-kB, nuclear factor kB; PET, positron emission tomography; QoL, quality of life; TAM, tumor-associated macrophage; TIL, tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte; ΔSUVmax, maximum change in standardized uptake value.

Patients with early relapse

Early relapse is usually defined as relapse in the year after diagnosis or the 6 months after the end of treatment. Although these patients achieved CR with the planned treatment, they then experienced quick progression, with lymphoma cells not responding to subsequent treatment. In addition, these patients frequently present with a central nervous system relapse, which is always associated with poor outcome.10 There is typically a clonal evolution among lymphoma cells, with some heterogeneity of genes involved in lymphoma growth that might explain the chemorefractoriness and difficulties of salvage.11 Furthermore, it has also been shown that DLBCL pathogenesis is strongly related to epigenetic perturbations and that high epigenomic heterogeneity correlated with a higher relapse rate and poor outcome.12 These observations open the pathway to specific DNA methyltransferase and histone methyltransferase inhibitors designed to erase aberrant epigenetic programming.13 Several studies have investigated the genetic landscape of relapsing DLBCL patients and identified TP53, FOXO1, MLL3, CCND3, NFKBIZ, and STAT6 as top candidate genes for therapeutic resistance.14

Patients with late relapse

Late-relapsing patients are characterized by a better response to salvage chemotherapy along with longer PFS and OS than those with refractory disease or early relapse.15 However, there is not a single parameter at diagnosis or at the time of CR that would allow us to recognize patients likely to relapse, nor are there any parameters to help discriminate early from late relapses. Conversely, not all the parameters described in Table 1 have been prospectively or retrospectively tested in relation to these different end points.

Strategies for refractory patients

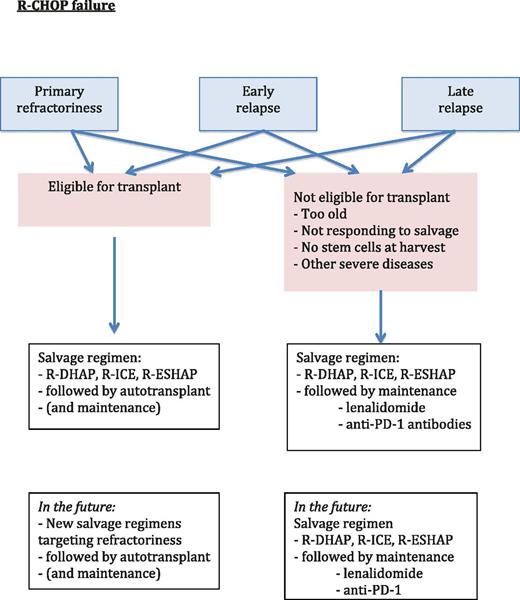

At present, we are not able to identify patients who will ultimately prove to be refractory before we initiate chemotherapy. Those patients typically receive standard chemotherapy with R-CHOP. However, given their poor prognosis, it may be better to focus on patients presenting with DHL, THL, or DPL and attempt to improve their first-line treatment regimen. Before initiating a randomized study, however, we must identify the drugs that would likely lead to a good response in refractory or relapsed patients. What is currently done for these patients is shown in Figure 2.

Suggested algorithm for therapy in patients for whom R-CHOP therapy failed.

New drugs and their association in refractory and relapsed patients

Table 2 provides a listing of new drugs that have been tested in refractory or relapsing patients. Most of these drugs display low activity and were mainly tested in relapsing but not in refractory patients; none of the drugs were specifically evaluated in patients with DHL or DPL. Table 3 provides an overview of the different regimens that are associated with a novel agent. Most regimens have been used for years and have been shown to result in an approximately 50% response, including a 30% CR rate, which is not much better than the responses obtained with standard rituximab plus ifosfamide, carboplatin and etoposide (R-ICE), rituximab plus dexamethasone, cytarabine, and cisplatin (R-DHAP), rituximab plus etoposide, methylprednisolone, cytarabine, and cisplatin (R-ESHAP), or rituximab plus gemcitabine, cisplatin, and methylprednisolone (R-GEM-P). Of all these studies, one conducted by the Lymphoma Study Association investigated the efficacy of 2 different regimens (R-DHAP and R-ICE) followed by autologous transplant in responders, depending on their MYC rearranged status.16 In that study, complex hits (DHL, THL, and others) were observed in 75% of the patients representing 17% of the entire patient population. The 4-year PFS and OS were significantly lower in DLBCL patients with MYC rearrangement than in those without, with rates of 18% vs 42% (P = .0322) and 29% vs 62% (P = .0113), respectively. The chemotherapy regimen (R-DHAP or R-ICE) had no impact on survival in either group.

Drugs associated with good response in progressing patients for whom R-CHOP chemotherapy failed

| Reference . | Drug . | MOA . | No. of patients/cell lines . | ORR . | PFS . | Toxicity . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 124 | Valproic acid | HDAC inhibitors | Cell lines | Increased apoptosis and DNA damage | ||

| 125 | OTX015 | Bromodomain and extraterminal inhibitor | 22 (17 evaluable) | 3 patients (1 of 5 patients was MYC positive) | NA | Thrombocytopenia |

| 126 | Imexon | Pro-oxidant molecule | 5 | 2 patients | 3 mo | Anemia, neutropenia |

| 127 | Vatalanib | VEGFR inhibitor | 18 | 1 CR | NA | Thrombocytopenia |

| 128 | Sunitinib | VEGFR kinase inhibitor | 17 | None | NA | Neutropenia, thrombocytopenia |

| 129 | Lenalidomide | Immunomodulatory agent, antiproliferative and antiangiogenic effects, others | ||||

| 130 | Coltuximab ravtansine | Anti-CD19 ADC | 45 | 31% | 3.9 mo | Gastrointestinal disorders, anemia |

| 131 | Pixantrone | Aza-anthracenedione | 92 | 24% (10% CR); less in refractory patients | 2 mo | Infections |

| 132 | Fostamatinib | Spleen tyrosine kinase inhibitor | 68 | 3% | Diarrhea, nausea, fatigue | |

| 133 | Rentuximab vedotin | Anti-CD30 ADC (in patients with CD30+) | 49 | 44% (17% CR) | DOR, 5.6 mo | Neutropenia |

| 134 | Cerdulatinib | Dual SYK/JAK kinase inhibitor | Cell lines | Induction of apoptosis, inhibition of RB phosphorylation | ||

| 135 | Obinutuzumab | Type II, glycoengineered humanized anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody | 25 | 32% | 2.7 mo | Infusion-related reactions |

| 136 | Anti-CD22 and anti-79b ADC | Antibody-drug conjugates linked to MMAE | ||||

| 137 | Belinostat | HDAC inhibitor | 22 | 10.5% | 2.1 mo | Well tolerated |

| 138 | Blinatumomab | Bi-specific T-cell engager | 21 | 43% (19% CR) | 3.7 mo | Tremor, pyrexia, fatigue, edema |

| 139 | Ibrutinib | Inhibitor of BCR signaling | 80 | 37% in ABC and 5% in GCB lymphoma | 2 mo in ABC and 1.3 mo in GCB lymphoma | NA |

| 140 | Small mimetics | Mediators of BCR-dependent NF-kB activity (cIAP1/cIAP2) | Cell lines | IKK activation, suppression of NF-kB in ABC cell lines | ||

| 23 | Venetoclax | BCL2 inhibitor | ||||

| 141 | Dacetuzumab | Anti-CD40 monoclonal antibody | 46 | 9% | 36 d | Fatigue, chills, fever |

| 142 | CC-122 | Pleiotropic pathway modifier promoting degradation of Aiolos and Ikaros in mice |

| Reference . | Drug . | MOA . | No. of patients/cell lines . | ORR . | PFS . | Toxicity . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 124 | Valproic acid | HDAC inhibitors | Cell lines | Increased apoptosis and DNA damage | ||

| 125 | OTX015 | Bromodomain and extraterminal inhibitor | 22 (17 evaluable) | 3 patients (1 of 5 patients was MYC positive) | NA | Thrombocytopenia |

| 126 | Imexon | Pro-oxidant molecule | 5 | 2 patients | 3 mo | Anemia, neutropenia |

| 127 | Vatalanib | VEGFR inhibitor | 18 | 1 CR | NA | Thrombocytopenia |

| 128 | Sunitinib | VEGFR kinase inhibitor | 17 | None | NA | Neutropenia, thrombocytopenia |

| 129 | Lenalidomide | Immunomodulatory agent, antiproliferative and antiangiogenic effects, others | ||||

| 130 | Coltuximab ravtansine | Anti-CD19 ADC | 45 | 31% | 3.9 mo | Gastrointestinal disorders, anemia |

| 131 | Pixantrone | Aza-anthracenedione | 92 | 24% (10% CR); less in refractory patients | 2 mo | Infections |

| 132 | Fostamatinib | Spleen tyrosine kinase inhibitor | 68 | 3% | Diarrhea, nausea, fatigue | |

| 133 | Rentuximab vedotin | Anti-CD30 ADC (in patients with CD30+) | 49 | 44% (17% CR) | DOR, 5.6 mo | Neutropenia |

| 134 | Cerdulatinib | Dual SYK/JAK kinase inhibitor | Cell lines | Induction of apoptosis, inhibition of RB phosphorylation | ||

| 135 | Obinutuzumab | Type II, glycoengineered humanized anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody | 25 | 32% | 2.7 mo | Infusion-related reactions |

| 136 | Anti-CD22 and anti-79b ADC | Antibody-drug conjugates linked to MMAE | ||||

| 137 | Belinostat | HDAC inhibitor | 22 | 10.5% | 2.1 mo | Well tolerated |

| 138 | Blinatumomab | Bi-specific T-cell engager | 21 | 43% (19% CR) | 3.7 mo | Tremor, pyrexia, fatigue, edema |

| 139 | Ibrutinib | Inhibitor of BCR signaling | 80 | 37% in ABC and 5% in GCB lymphoma | 2 mo in ABC and 1.3 mo in GCB lymphoma | NA |

| 140 | Small mimetics | Mediators of BCR-dependent NF-kB activity (cIAP1/cIAP2) | Cell lines | IKK activation, suppression of NF-kB in ABC cell lines | ||

| 23 | Venetoclax | BCL2 inhibitor | ||||

| 141 | Dacetuzumab | Anti-CD40 monoclonal antibody | 46 | 9% | 36 d | Fatigue, chills, fever |

| 142 | CC-122 | Pleiotropic pathway modifier promoting degradation of Aiolos and Ikaros in mice |

ADC, antibody-drug conjugate; cIAP1, cellular inhibitor of apoptosis protein-1; DOR, duration of response HDAC, histone deacetylase; IKK, IκB kinase; MMAE, monomethyl auristatin E; MOA, mechanism of action; NA, not applicable; ORR, overall response rate; RB, retinoblastoma protein; VEGFR, vascular endothelial growth factor receptor.

Regimens associated with good response in progressing patients for whom R-CHOP chemotherapy failed

| Reference . | Regimen . | Drug tested . | No. of patients . | ORR (%) . | CR or PR (%) . | PFS . | Toxicity . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 143 | Bendamustine-rituximab | Combination, patients not eligible for BMT | 55 | 50 | 28 | 8.8 mo | Moderate |

| 144 | R-GEM-P | 45 | 61 | 22% (3-y) | Neutropenia, thrombocytopenia | ||

| 145 | Bendamustine-rituximab-lenalidomide | Test the addition of lenalidomide | 11 | 5 patients | NA | Neutropenia | |

| 16 | R-ICE/R-DHAP | In patients with MYC rearrangement, 75% with complex hits | 28 | 50 | 18% (4-y) | ||

| 146 | Bortezomib-gemcitabine | Test bortezomib | 16 | 10 | NA | Neutropenia, thrombocytopenia | |

| 147 | R-ICE + dacetuzumab | Phase 3 testing of dacetuzumab (interrupted for futility) | 75 | 67 | 33 | 12.1 mo | Febrile neutropenia |

| 148 | Rituximab + inotuzumab ozogamicin | Inotuzumab ozogamicin | 118 | 74 relapsed, 20 refractory | 17.1 mo | Thrombocytopenia, neutropenia | |

| 149 | R-ICE + lenalidomide | Test lenalidomide with autologous transplant | 15 | 73 | NA | Well tolerated | |

| 150 | Rituximab-gemcitabine + dacetuzumab | Test dacetuzumab | 30 | 47 | 20 | NA | Well tolerated |

| 151 | Bendamustine-rituximab + YM155 | Test YM155, a survivin suppressant in mice | |||||

| 152 | Anti-CD19 CAR-T cells | First report in lymphoma | 15 | 80 | 53 | 11 mo | Fever, hypotension |

| 153 | Alisertib + vincristine-rituximab | In DPL in mice; high synergy between alisertib, vincristine, and rituximab | |||||

| 154 | R-ESHAP + lenalidomide | Test the addition of lenalidomide | 19 | 79 | 47 | 44% (2-y) | Cytopenias |

| 155 | Ofatumumab + ICE/DHAP | Test ofatumumab in place of rituximab | 61 | 61 | 37 | 9.5 mo | Cytopenias, febrile neutropenia |

| 156 | R-P-IMVP16/CBDCA | Retrospective analysis | 59 | 64 | 34.7% (2-y) | Neutropenia, thrombocytopenia | |

| 157 | Vorinostat + CVEP | 23 | 57 | 35 | 9.2 mo | Lymphopenia | |

| 158 | Bendamustine-rituximab | 48 | 45.8 | 15.3 | 3.6 mo | Neutropenia | |

| 159 | CUDC-907 | Phase 1 of this dual inhibitor (HDAC and PI3K) | 44 | 14 | 2 CR; 3 PR | 2.4 mo | Thrombocytopenia, neutropenia, hyperglycemia |

| Reference . | Regimen . | Drug tested . | No. of patients . | ORR (%) . | CR or PR (%) . | PFS . | Toxicity . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 143 | Bendamustine-rituximab | Combination, patients not eligible for BMT | 55 | 50 | 28 | 8.8 mo | Moderate |

| 144 | R-GEM-P | 45 | 61 | 22% (3-y) | Neutropenia, thrombocytopenia | ||

| 145 | Bendamustine-rituximab-lenalidomide | Test the addition of lenalidomide | 11 | 5 patients | NA | Neutropenia | |

| 16 | R-ICE/R-DHAP | In patients with MYC rearrangement, 75% with complex hits | 28 | 50 | 18% (4-y) | ||

| 146 | Bortezomib-gemcitabine | Test bortezomib | 16 | 10 | NA | Neutropenia, thrombocytopenia | |

| 147 | R-ICE + dacetuzumab | Phase 3 testing of dacetuzumab (interrupted for futility) | 75 | 67 | 33 | 12.1 mo | Febrile neutropenia |

| 148 | Rituximab + inotuzumab ozogamicin | Inotuzumab ozogamicin | 118 | 74 relapsed, 20 refractory | 17.1 mo | Thrombocytopenia, neutropenia | |

| 149 | R-ICE + lenalidomide | Test lenalidomide with autologous transplant | 15 | 73 | NA | Well tolerated | |

| 150 | Rituximab-gemcitabine + dacetuzumab | Test dacetuzumab | 30 | 47 | 20 | NA | Well tolerated |

| 151 | Bendamustine-rituximab + YM155 | Test YM155, a survivin suppressant in mice | |||||

| 152 | Anti-CD19 CAR-T cells | First report in lymphoma | 15 | 80 | 53 | 11 mo | Fever, hypotension |

| 153 | Alisertib + vincristine-rituximab | In DPL in mice; high synergy between alisertib, vincristine, and rituximab | |||||

| 154 | R-ESHAP + lenalidomide | Test the addition of lenalidomide | 19 | 79 | 47 | 44% (2-y) | Cytopenias |

| 155 | Ofatumumab + ICE/DHAP | Test ofatumumab in place of rituximab | 61 | 61 | 37 | 9.5 mo | Cytopenias, febrile neutropenia |

| 156 | R-P-IMVP16/CBDCA | Retrospective analysis | 59 | 64 | 34.7% (2-y) | Neutropenia, thrombocytopenia | |

| 157 | Vorinostat + CVEP | 23 | 57 | 35 | 9.2 mo | Lymphopenia | |

| 158 | Bendamustine-rituximab | 48 | 45.8 | 15.3 | 3.6 mo | Neutropenia | |

| 159 | CUDC-907 | Phase 1 of this dual inhibitor (HDAC and PI3K) | 44 | 14 | 2 CR; 3 PR | 2.4 mo | Thrombocytopenia, neutropenia, hyperglycemia |

BMT, bone marrow transplantation; CAR, chimeric antigen receptor; CBDCA, carboplatin; CVEP, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, etoposide, and prednisone; PI3K, phosphoinositide 3-kinase; R-GEM-P, rituximab plus gemcitabine, cisplatin, and methylprednisolone; R-P-IMVP16, rituximab, methylprednisolone, ifosfamide, methotrexate, and etoposide.

A better regimen than R-CHOP for high-risk patients

Intensified R-CHOP.

In general, refractory patients and relapsing patients receive the same salvage treatment (R-DHAP, R-ICE, or R-ESHAP followed by autologous transplant in responders), even when they are refractory to standard therapy. Another strategy would be to fine-tune the R-CHOP regimen. In a retrospective analysis, the MD Anderson group examined a total of 129 DHL patients treated with R-CHOP, dose-adjusted rituximab plus etoposide, prednisone, vincristine, cyclophosphamide, and doxorubicin (DA-R-EPOCH), or rituximab plus hyperfractionated cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin, and dexamethasone alternating with high-dose methotrexate-cytarabine (R-hyperCVAD/MA) and found that patients receiving either DA-R-EPOCH or R-hyperCVAD/MA experienced a better outcome.17 R-hyperCVAD/MA was significantly associated with higher CR rates compared with R-CHOP, whereas DA-R-EPOCH resulted in longer EFS than R-CHOP.17 The efficacy of these intensified or dose-escalated regimens was corroborated in another study.18 The results of that study are waiting to be confirmed in a randomized, currently ongoing study (R-CHOP vs DA-R-EPOCH; NCT00118209). The studies assessing the benefit of high-dose therapy plus autologous transplant in first CR, however, showed no improvement over chemotherapy alone.19

The only possibility for increasing cure rates is either to increase the number of true CR patients or to implement maintenance treatment in these CR patients. At least 1 randomized study has compared R-CHOP to a more intensive regimen (rituximab plus doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, vindesine, bleomycin, and prednisone [R-ACVBP]) in young patients with adverse prognostic parameters (age-adjusted International Prognostic Index score of 1), showing that, in spite of similar CR rates between the 2 arms, a significant statistical difference in favor of the R-ACVBP regimen was found in terms of EFS, disease-free progression, PFS, and OS.20 Another study confirmed that first-line dose-escalated immunochemotherapy resulted in a significant PFS advantage in DHL patients.18

Associations with new agents at diagnosis.

Given that intensified regimens may not be appropriate for all patients and may be associated with higher toxicity, a better strategy for treating high-risk patients would be to use a regimen other than R-CHOP. Although such a regimen has not yet been identified, some of the new drugs may prove efficacious in this setting and may thus be incorporated into new therapeutic regimens.

Because a large proportion of refractory patients have been shown to have DHL or DPL, targeting MYC or BCL2 might be a solution. Although there are very few studies conducted in DHL or DPL patients, some responses may be drawn from studies targeting the broader group of relapsed or refractory patients. The first-in-class BCL2 inhibitor, navitoclax, which is an inhibitor of BCL2, BCLx, and BCLw, was tested.21 However, the development of navitoclax was postponed because of associated severe thrombocytopenia. In contrast, venetoclax (ABT-199), another selective inhibitor of BCL2, was not associated with thrombocytopenia.22 Several studies have already demonstrated the clinical benefit of venetoclax in relapsing chronic lymphocytic leukemia patients, whereas studies in patients with DLBCL are still ongoing.23

Several agents aimed at modulating MYC expression or activity are presently undergoing clinical development. Mainly negative results have been reported so far,24 but agents targeting epigenetic regions could be a good option for reducing MYC expression. BET bromodomain inhibitors mitigate the effect of MYC overexpression by preventing signal transduction.25 JQ1 inhibits the bromodomain BRD4, but the compound has been tested only in preclinical models so far.26 Other inhibitors are currently undergoing phase 1 evaluation in refractory lymphoma patients (GSK525762 [NCT01943851], CUDC-907 [NCT01742988], and CPI-0610 [NCT01949883]).

Other therapies targeting MYC-dependent cancer metabolism could be used in DHL and DPL. Agents targeting glucose metabolism, shown to be upregulated in cells overexpressing MYC, are being developed. An example of this is AZD3965, a specific inhibitor of the monocarboxylate transporter 1 (MCT1), which was shown in mice to lead to lactate accumulation and lower cellular pH, and it inhibits glycolysis and growth of lymphoma. AZD3965 is being tested in a phase 1 trial (NCT01791595) involving patients with DLBCL or other solid cancers.

Strategies for relapsing patients

Early relapses (in the year following treatment initiation) are associated with the same dismal outcome as refractoriness, and thus these patients should be treated by using the same strategy.15

At present, no standard regimen has been defined for relapsing DLBCL patients.27 A good salvage regimen would be associated with high CR rates (above 60%), which would allow a transplant to have a higher success rate.28 To prolong PFS after salvage therapy, maintenance therapy (described below) should be considered. When using that strategy, ∼60% of late-relapse patients survive longer than 5 years.

Patients relapse because they develop drug resistance by means of different mechanisms, such as intrinsic genetic resistance associated with recurrent translocations and specific gene abnormalities, treatment-acquired resistance secondary to genetic and epigenetic instability, emergence of drug-resistant subclones, and tumor microenvironment-mediated drug resistance.29

Patients with PR

Patients who responded to R-CHOP without achieving CR because of persisting lymphoma cells as shown on biopsy (bone marrow or lymph nodes) or persisting positivity on PET scan at the end of treatment may respond to a different drug regimen. Patients with PR will likely progress and must be treated before the progression occurs. Typically, patients are given one of the standard salvage regimens (R-DHAP, R-ICE, or R-ESHAP) followed by autologous transplant, if possible.

Patients not eligible for transplant

When patients are not eligible for either intensified R-CHOP or autologous stem cell transplantation, there are no good salvage options for this very difficult situation. One solution consists of using a maintenance strategy after R-CHOP that is aimed to delay or eliminate relapse. When new regimens are defined for younger patients, they should also be tested for elderly patients.

In DLBCL patients, 6 drugs have been or are being tested in phase 3 trials for maintenance in CR or PR patients in an effort to prolong remission—rituximab, enzastaurin, lenalidomide, everolimus, radioimmunotherapy (90Y-ibritumomab tiuxetan or 131I-tositumomab), and anti-PD-1 antibodies. Enzastaurin and everolimus after R-CHOP failed to show any benefits.30,31 Rituximab has been investigated in 3 studies, 2 after autologous transplant and 1 as first-line treatment. The differences in PFS or OS were not significant, but there was a trend in favor of maintenance therapy.32

90Y-ibritumomab tiuxetan has been used as consolidation alone after R-CHOP or in combination with carmustine, etoposide, cytarabine, and melphalan (Z-BEAM) before autologous transplant. One randomized study has been published that compares carmustine, etoposide, cytarabine, and melphalan (BEAM) and Z-BEAM and reports a possible benefit in favor of Z-BEAM.33 Another study using 131I-tositumomab-BEAM in comparison with rituximab-BEAM did not reveal any differences between the 2 arms.34 In a phase 2 study with 131I-tositumomab given as consolidation after R-CHOP, the CR rate and PFS were not better than with R-CHOP alone in this patient subset.35 In another phase 2 study with 90Y-ibritumomab tiuxetan consolidation after R-CHOP, a longer PFS was observed than is usually described (5-year PFS, 78%).36 In all of these studies, the sample size was small, and none of the studies reported results for especially aggressive lymphomas such as DHL.

Lenalidomide maintenance has been tested in a phase 2 study in relapsing patients with DLBCL who achieved either CR or PR. In that study, there was some conversion of PR to CR on PET scans, and PFS proved to be longer than expected (1-year PFS, 79%).37 A large randomized study (REMARC) compared lenalidomide with placebo in 650 elderly DLBCL patients in PR or CR. The final study will be presented at an American Society of Hematology Annual Meeting and Exposition, with the primary end point (increased median PFS) achieved in the arm treated with lenalidomide compared with placebo.

Immune checkpoint inhibitors have proved to be efficacious in solid tumors and relapsing Hodgkin lymphomas. These agents are currently being tested in relapsing DLBCLs and other lymphomas.38 If they appear to be efficacious in these settings, they should be tested as maintenance consolidation in high-risk patients or relapsing patients.

Conclusion

At present, we have a definition for refractory patients but not for relapsing patients. R-CHOP does not seem to be a good therapeutic regimen for either DHL or DPL, but we do not have a better solution at this time. Although new drugs that target MYC and BCL2 are eagerly awaited, it will probably take several months or years before a good regimen is identified. For relapsing patients, immunomodulatory agents that are currently being used to maintain CR are a strategy that may be applicable to both elderly and young patients.

Correspondence

Bertrand Coiffier, Hematology Department, Centre Hospitalier Lyon-Sud, 69310 Pierre-Bénite, France; e-mail: bertrand.coiffier@chu-lyon.fr.

References

Competing Interests

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: B.C. is on the board of directors or an advisory committee for Celgene, Celltrion, MorphoSys, and Pfizer and has consulted for Gilead and Novartis. C.S. declares no competing financial interests.

Author notes

Off-label drug use: None disclosed.