Abstract

Recent progress in next-generation sequencing strategies has revealed the genetic landscape of B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma, but the tumor microenvironment is increasingly recognized as crucial to sustaining malignant B-cell survival and growth, subclonal evolution, and drug resistance. The tumor niche is made up of a dynamic and organized network of strongly heterogeneous immune and stromal cell subsets characterized by specific phenotypic, transcriptomic, and functional features. Nonmalignant cell recruitment and plasticity are dictated by lymphoma B cells, which convert their surrounding microenvironment into a supportive niche. In addition, they are also influenced by the crosstalk between the various components of this niche. In agreement with this, the B-cell lymphoma subtype is a key determinant of the organization of the tumor niche, but genetic alteration patterns, tumor localization, stage of the disease, and treatment strategy may also modulate its composition and activity. Moreover, the complex set of bidirectional interactions between B cells and their microenvironment has been proposed as a promising therapeutic target with the aim of reinforcing antitumor immunity and/or of abbrogating the lymphoma-promoting signals delivered by the tumor niche.

Learning Objectives

To understand how the dynamic interplay between lymphoma B cells and their tumor microenvironment triggers the building of a supportive niche integrating immune escape mechanisms and B-cell survival and proliferation signals

To recognize the main limitations, challenges, and open questions in the field of the tumor lymphoma microenvironment

Introduction

B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma (B-NHL) comprises a group of highly heterogeneous tumors characterized by a disseminated infiltration of lymphoid structures by malignant mature B cells. Each lymphoma subtype can be assigned to a unique stage of B-cell differentiation and harbors a panel of genetic alterations sustaining specific transformation pathways and disease evolution.1 Follicular lymphoma (FL) and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) together account for about 70% of B-NHL and are derived from germinal center (GC) B cells at various stages of GC transit, namely centrocytes of the GC light zone for FL and GC B-cell (GCB)-like DLBCL as well as committed post-GC plasmablasts for DLBCL of the activated B-cell (ABC) phenotype. Histological transformation of indolent FL to aggressive lymphoma, more closely related to GCB-DLBCL, occurs in about 35% of cases and is associated with poor outcome. Genome-wide profiling has recently shed new light on the mutational landscape of both FL and DLBCL, thus providing considerable advancement in the understanding of lymphomagenesis. However, tumors are now widely recognized as complex and dynamic ecosystems supporting coevolution of malignant cells and their surrounding microenvironment, whose quantitative and qualitative composition influences tumor initiation, growth, and progression; immune escape; and drug resistance. Interestingly, FL and DLBCL are characterized by different patterns of tumor niche organization, a phenomenon that could contribute to their different clinical course and should be considered in the development of new therapeutic strategies.2 In agreement with this observation, it is virtually impossible to maintain FL B cells in vitro, whereas numerous DLBCL cell lines of both the GC and ABC phenotypes have successfully been established. This review is focused on these two frequent B-NHL subsets in order to highlight the main recent advances and unsolved questions regarding the role of the microenvironment in lymphomagenesis.

Lymphoma microenvironment challenges

FL is characterized by a long preclinical stage and an indolent clinical course with multiple relapses, and it retains a substantial degree of dependence on a specific GC-like microenvironment, including in particular specialized subsets of CD4pos T cells, stromal cells, and macrophages.3 Moreover, this lymphoid-like microenvironment is ectopically induced in FL-invaded bone marrow (BM), where paratrabecular nodular aggregates of malignant B cells are enriched for functional lymphoid-like stromal cells and CD4pos T cells.4 Accordingly, immunohistochemical and transcriptomic studies have provided a large panel of predictive biomarkers reflecting the quantitative and qualitative composition as well as the spatial organization of FL lymph node (LN)-infiltrating immune cells.3 FL B-cell cytological grade, proliferation rate, and subclonal evolution differ between LN and BM, suggesting that trafficking within different microenvironments could impact FL phenotypic and molecular heterogeneity. DLBCL is described as less dependent on its microenvironment, in agreement with a complete disorganization of normal lymphoid structure. Interestingly, Gα13-dependent signaling is crucial to maintaining normal GC B-cell confinement, and this pathway is frequently mutated in GC-DLBCL and transformed FL, allowing malignant B-cell dissemination and favoring microenvironment-independent B-cell survival.5,6 However, besides the widely used GC/ABC classification reflecting malignant B-cell features, two gene expression profiling studies have highlighted another level of DLBCL biological heterogeneity underlying the role of the microenvironment. In the first one, a host response signature was identified, related to immune activation, and was associated with unique clinical features.7 In the second one, a prognostically favorable stromal-1 signature, associated with extracellular matrix deposition and myeloid cell infiltration, and a prognostically unfavorable stromal-2 signature, reflecting tumor blood vessel density, were characterized.8 These studies suggest that microenvironment features contribute to FL/DLBCL pathogenesis. However, they have shown highly contradictory results concerning their impact on patient outcome, at least partly due to the heterogeneity in the patient cohorts and treatment schedules as well as to substantial technical hurdles limiting data reproducibility. In addition, such descriptive studies do not provide any mechanistic insights into the functional role of lymphoma cell niches.

The main biological limitation to a comprehensive analysis of the microenvironment in B-cell malignancies is related to the heterogeneity and plasticity of the numerous and sometimes very rare cell subsets involved. Such diversity could not be efficiently captured by the low-resolution tools classically used, a phenomenon recently amplified by the reduced size of available biological samples related to the increasing use of fine-needle biopsies. As an example, multicolor flow cytometry/cell sorting strategies and in vitro assays were required to pinpoint that the majority of PD-1–expressing CD4pos T cells in FL are fully functional PD-1hi CXCR5hiTim-3neg follicular helper T cells (Tfh),9,10 opposing the previous hypothesis that they represent exhausted T cells.11 Based on such more comprehensive technical approaches, the main open questions challenge

The quantitative, qualitative, spatial, and functional heterogeneity of the lymphoma microenvironment, taking into account tumor genetic alterations, tumor localization (LN vs BM), stage of the disease, and impact of treatment;

The origin of lymphoma microenvironment subsets, including the identification of precursor cells and commitment pathways; and

The clinical relevance of the prognostic/stratification markers relying on lymphoma microenvironment characterization and its potential as a target for new therapeutic options.

These major fields of investigation should be considered for both the antitumoral and protumoral facets of the tumor microenvironment.

Antitumoral microenvironment

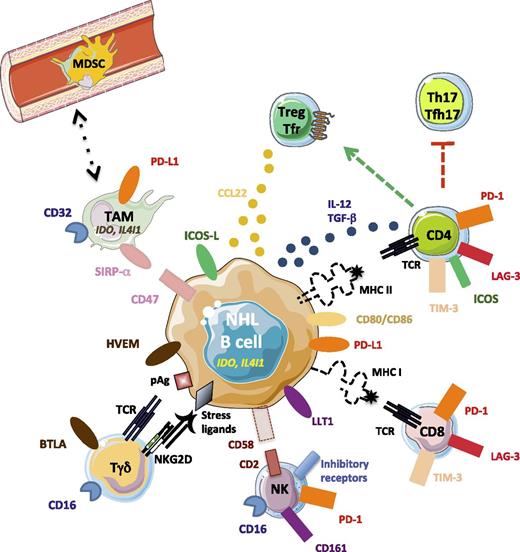

FL has long been considered as immune responsive on the basis of high response rates to anti-CD20 monoclonal antibodies associated with a long-lasting vaccinal effect, good biological responses to idiotype vaccines, and interesting response rates in recent clinical trials involving immunomodulatory drugs such as lenalidomide or immune checkpoint inhibitors. In DLBCL, immunochemotherapy is also the standard of care, and soluble PD-L1 has recently emerged as a powerful prognostic biomarker,12 suggesting a role for the immune system in the control of disease progression. Several immune cell subsets contribute to this antitumor activity, and conversely lymphoma cells escape or dampen antitumor immunity through modifications of malignant B-cell phenotypes and induction or recruitment of a suppressive microenvironment (Figure 1).

Immune escape mechanisms in B-NHL. Malignant B cells progressively lose surface molecules involved in recognition by CD4 (major histocompatibility complex II), CD8 (major histocompatibility complex I), and NK (CD58) cells, whereas they variably overexpress inhibitory receptors, including PD-L1, LLT1, HVEM, and CD47, which are the ligands for PD-1, CD161, BTLA, and SIRP-α, and produce the inhibitory enzymes IDO and IL4I1. The combination of these mechanisms allows them to avoid killing by cytotoxic cells and phagocytosis by TAM. In addition, they contribute to Treg recruitment and differentiation, as well as to exhaustion of T-effector cells through the release of CCL22, TGF-β, and IL-12 and the expression of ICOSL and CD80/CD86. pAg, phosphoantigen.

Immune escape mechanisms in B-NHL. Malignant B cells progressively lose surface molecules involved in recognition by CD4 (major histocompatibility complex II), CD8 (major histocompatibility complex I), and NK (CD58) cells, whereas they variably overexpress inhibitory receptors, including PD-L1, LLT1, HVEM, and CD47, which are the ligands for PD-1, CD161, BTLA, and SIRP-α, and produce the inhibitory enzymes IDO and IL4I1. The combination of these mechanisms allows them to avoid killing by cytotoxic cells and phagocytosis by TAM. In addition, they contribute to Treg recruitment and differentiation, as well as to exhaustion of T-effector cells through the release of CCL22, TGF-β, and IL-12 and the expression of ICOSL and CD80/CD86. pAg, phosphoantigen.

Immune response

Cytotoxic lymphoid cells, including CD8pos T cells, γδT cells, and natural killer (NK) cells, play a central role in antilymphoma immunity. Importantly, the cells of origin of B-cell lymphomas are professional antigen-presenting cells and constitutively express major histocompatibility complex class II molecules involved in antigen presentation to CD4pos T cells, a crucial step in the initiation of the immune response. In parallel, dendritic cell (DC) frequency is reduced in FL, as previously described in several tumor models.13 As expected, a high CD4pos T-cell infiltration, essentially of the memory phenotype, has been correlated with increased overall survival and a lower malignant B-cell proliferation rate in patients with DLBCL.14 In FL, where different populations of CD4pos T cells could restrain or favor B-cell growth, increased CD3pos and CD8pos but not CD4pos T-cell infiltrates have been reproducibly correlated with a better clinical outcome.15 Moreover, a rich infiltrate of CD8pos T cells expressing the pore-forming protein granzyme B and engaged in lytic-like structures with FL B cells was detected at the FL follicle border.16 Even if few studies have directly addressed the question of lymphoma-infiltrating NK cells in situ, they contribute to the activity of antitumor antibodies through antibody-dependent cell cytotoxicity, as highlighted by the impact of the CD16/FcRγIIIA-V158F polymorphism on the clinical response to rituximab. Finally, Vγ9δ2 T cells recognizing tumor phosphoantigens are able to kill lymphoma B cells in vitro.17 Interestingly, whereas they represent a minority of γδ T cells in peripheral blood from healthy individuals, Vδ1 T lymphocytes, responding to stress-associated ligands, are expanded in patients with FL and patients with DLBCL.18,19 Of note, Vδ2neg T cells are known to express CD16 in individuals with cytomegalovirus infection and to display antibody-dependent cell cytotoxicity potential, suggesting that they could contribute to anti-CD20 activity in B-NHL.20

Tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) exhibit a dual role in FL and DLBCL pathogenesis, as underlined by the opposite predictive value of TAM content depending on treatment schedule.3,21 Whereas a high number of TAMs was essentially associated with poor outcome in patients treated with chemotherapy, elevated CD68 and/or CD163 staining was associated with a favorable prognosis when patients were treated with rituximab. These data could be related to the demonstration that CD163pos M2-polarized macrophages display high phagocytic capacity toward rituximab-opsonized targets.22 Interestingly, the blockade of the “don’t eat me” molecule CD47, overexpressed on FL and DLBCL B cells, increases in vitro and in vivo the phagocytic activity of macrophages expressing the inhibitory receptor SIRP-α, suggesting that tumor cells exploit the suppressive CD47–SIRP-α axis to evade macrophage-mediated destruction.23

Overall, activated cytotoxic and phagocytic cells from innate and adaptive immunity directly kill malignant B cells and release inflammatory cytokines that could contribute to their reciprocal activation. However, this antitumor immune response is counteracted by tumor escape mechanisms.

Mechanisms of immune evasion and subversion

The first mechanism of immune evasion is the reduction of tumor immunogenicity related to a panel of genetic alterations triggering a lack of malignant B-cell recognition by CD4pos T, CD8pos T, and NK cells2,24 (Table 1). The second driving mechanism of tumor escape is the reduced T-cell antitumoral activity. FL-infiltrating T cells display a decreased F-actin polymerization at the immunological synapse25 and an impaired LFA-1–dependent motility,26 indicating alteration of cytoskeleton-dependent T-cell activation. These defects, also detected in DLBCL-infiltrating T cells, could be induced in vitro in healthy donor T cells by direct contact with malignant B cells and could be reversed, at least partly, by lenalidomide. It was proposed that expression of multiple cell surface inhibitory molecules by lymphoma cells, including CD200, PD-L1, or herpes virus entry mediator (HVEM), contribute to the impairment of the T-cell actin dynamic across hematologic B-cell malignancies.27 However, it should be keep in mind that PD-L1 expression is restricted to a subset of 20% to 30% of DLBCL, essentially of the non-GCB subtype, in relationship with different genetic alterations and inferior overall survival.28 Conversely, whereas infiltrating myeloid cells could express PD-L1 in both FL and DLBCL, FL B cells are PD-L1neg and display inactivating genetic alterations of HVEM in 30% to 40% of cases.29 Regardless of inhibitory receptor ligand expression by malignant cells and/or by their microenvironment, exhausted T cells harboring the corresponding receptors infiltrate B-cell lymphomas. TIM-3 and LAG-3 have emerged as good markers for functionally impaired FL-infiltrating T cells, whereas PD-1 expression is not sufficient to distinguish exhausted CD4pos T cells from immunologically competent Tfh.9,30,31 Finally, CD70 upregulation is associated with FL memory T-cell exhaustion and predicts inferior patient outcome.32 FL B-cell–derived interleukin-12 (IL-12) was proposed as a driving mechanism of TIM-3 and LAG-3 induction,30,33 whereas transforming growth factor-β triggers exhaustion of effector memory T cells.32 Interestingly, NK and Tγδ cells also express some inhibitory receptors, including PD-L1 and BTLA, and could thus be subverted by malignant B cells or TAM expressing the corresponding ligands. Moreover, LLT1 was recently identified as a marker of normal and malignant GC B cells, including FL and GC-DLBCL, and was shown to dampen NK cell functions through interaction with its receptor, CD161.34

Mechanisms of immune escape in FL and DLBCL

| Immune defect . | Proposed mechanisms . |

|---|---|

| Immune evasion | |

| Lack of recognition by CD4pos T cells | Loss of MHC class II |

| • MHC class II deletion | |

| • CREBBP mutations | |

| • Plasmablastic differentiation | |

| • Mutational landscape evolution | |

| Lack of recognition by CD8pos T cells | Loss of MHC class I |

| • β2M mutation or deletion | |

| • Mutational landscape evolution | |

| Lack of recognition by NK cells | Loss of CD58 |

| • Mutation or deletion | |

| Decreased phagocytosis | Overexpression of CD47 |

| Immune subversion | |

| Impaired T/NK activity | Expression of inhibitory molecules (CD200, PD-L1, HVEM, LLT1) |

| Production of IL-12 and TGF-β | |

| Production of IDO and IL4I1 | |

| Treg/Tfr amplification | Production of CCL22 |

| Expression of CD70, CD80/CD86, ICOSL, TGF-β | |

| Amplification of myeloid suppressive cells | Production of IL-10 |

| Amplification of suppressive nonhematopoietic cells (endothelial, stromal) | Unknown |

| Immune defect . | Proposed mechanisms . |

|---|---|

| Immune evasion | |

| Lack of recognition by CD4pos T cells | Loss of MHC class II |

| • MHC class II deletion | |

| • CREBBP mutations | |

| • Plasmablastic differentiation | |

| • Mutational landscape evolution | |

| Lack of recognition by CD8pos T cells | Loss of MHC class I |

| • β2M mutation or deletion | |

| • Mutational landscape evolution | |

| Lack of recognition by NK cells | Loss of CD58 |

| • Mutation or deletion | |

| Decreased phagocytosis | Overexpression of CD47 |

| Immune subversion | |

| Impaired T/NK activity | Expression of inhibitory molecules (CD200, PD-L1, HVEM, LLT1) |

| Production of IL-12 and TGF-β | |

| Production of IDO and IL4I1 | |

| Treg/Tfr amplification | Production of CCL22 |

| Expression of CD70, CD80/CD86, ICOSL, TGF-β | |

| Amplification of myeloid suppressive cells | Production of IL-10 |

| Amplification of suppressive nonhematopoietic cells (endothelial, stromal) | Unknown |

β2M, β2-microglobulin; IL, interleukin; MHC, major histocompatibility complex; Tfr, follicular regulatory T cells; TGF-β, transforming growth factor-β; Treg, regulatory T cells.

Besides the loss of T/NK cell activation, FL/DLBCL biopsies are also characterized by an expansion of immune-suppressive cells, in particular regulatory T cells (Treg). Malignant B cells have been shown to produce high amounts of the Treg-recruiting chemokine CCL22 in response to Tfh-derived IL-4 and CD40L signals35 and to skew the balance of T helper (Th) polarization toward FOXP3pos Treg and away from Th17.36 Expression of CD70, CD80/86, or membrane transforming growth factor-β has been involved in this process. Lymphoma-infiltrating Treg efficiently inhibit both CD4pos and CD8pos T-cell proliferation, and Treg frequency is inversely correlated with CD8pos T-cell frequency in B-NHL.37 A specificity of the Treg cell compartment in FL, unlike in DLBCL, is that, as described for effector Th cells, it includes both CXCR5negPD-1neg classical Treg and CXCR5posPD-1pos follicular regulatory T cells (Tfr).10 Tfr localize within normal GC and inhibit Tfh-mediated B-cell activation and antibody production, thus controlling the dynamic and extent of GC reaction.38 Fully functional Tfr are strongly expanded within the FL cell niche compared with reactive LN, and ICOSLpos FL B cells have been involved in this Tfr enrichment.39 Their role in FL pathogenesis is currently unknown, and the prognostic value of FOXP3pos Treg count in FL remains controversial.3

Besides Treg, myeloid cells could also contribute to immune suppression. In all B-cell lymphoma subtypes, TAMs have been shown to release interleukin-4–induced gene-1 (IL4I1) and indoleamine-2,3 dioxygenase (IDO), whereas IL4I1 is also produced by malignant B cells in FL and primary mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma and IDO by DLBCL B cells.40,41 These two amino acid–degrading, immunosuppressive enzymes are involved in the expansion of Treg and the blockade of effector T-cell proliferation and cytotoxicity. More recently, immature granulocyte and monocyte subsets have demonstrated their immunosuppressive function in cancers and inflammatory diseases and are recognized as myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs). Circulating CD14posHLA-DRlo monocytic MDSC count is elevated in patients with DLBCL and correlates to clinical outcome and Treg number.42 IL-10 has been proposed as an inducer of monocytic MDSC expansion in B-NHL,43 whereas MDSC-dependent T-cell suppression was attributed to IL-10, S100A12, and PD-L1 expression.42 Of note, even if their number was not shown to predict prognosis for patients with lymphoma, granulocytic MDSCs are also expanded in patients with DLBCL and correlate with the plasma level of the immunosuppressive enzyme arginase 1. The biological activity of MDSCs inside tumors and their relationship with TAMs remain to be explored. Finally, an interesting study has proposed that lymphoma-infiltrating endothelial cells overexpress TIM-3, thus facilitating immune evasion,44 and FL-infiltrating stromal cells have been shown to produce more prostaglandin E2, a well-known immunosuppressive factor, than their normal counterparts.45

In summary, the B-NHL immune microenvironment could be considered as a network of exhausted/suppressed antitumor cell subsets and recruited/activated suppressive cell compartments that dynamically interact with each other. Malignant B cells contribute to the organization of this favorable niche, as shown by the selection of lymphoma cells harboring genetic and phenotypic features favoring tumor escape.

Protumoral microenvironment

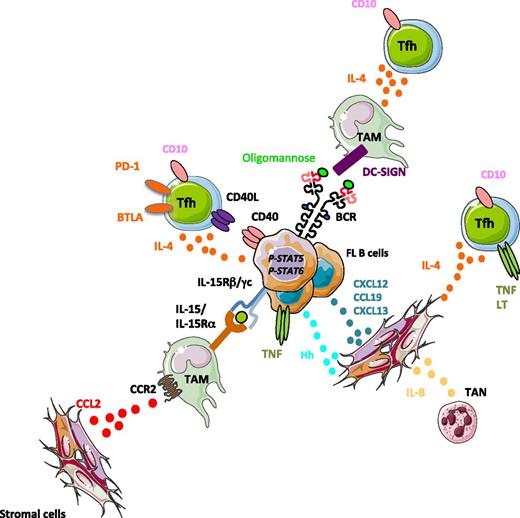

Besides the immune activation/immune escape active loop that supports continuous lymphoma immunoediting, the B-NHL microenvironment is also organized to provide survival and growth signals to malignant B cells through specialized immune and stromal cell subsets exhibiting specific polarization and activation profiles (Figure 2).

Tumor-supporting niche in FL. Three main cell subsets have been shown to support FL B-cell growth: (1) FL TAMs overexpress IL-15 that triggers STAT5-dependent FL B-cell activation, as well as DC-SIGN that aggregates FL-mannosylated BCR; (2) expanded FL Tfh activate directly malignant B cells through CD40L and IL-4 and favor indirectly the growth of the tumor by stimulating TAM and stromal cells through IL-4; and (3) stromal cells are committed to lymphoid stromal differentiation, in agreement with their contact with TNF-expressing malignant B cells, Tfh, and tumor-associated neutrophils (TAN), and they overexpress CCL2 and IL-8, thus more efficiently recruiting TAM and TAN. FL stromal cells are involved in malignant B-cell recruitment and survival through the release of chemokines and hedgehog (Hh) ligands.

Tumor-supporting niche in FL. Three main cell subsets have been shown to support FL B-cell growth: (1) FL TAMs overexpress IL-15 that triggers STAT5-dependent FL B-cell activation, as well as DC-SIGN that aggregates FL-mannosylated BCR; (2) expanded FL Tfh activate directly malignant B cells through CD40L and IL-4 and favor indirectly the growth of the tumor by stimulating TAM and stromal cells through IL-4; and (3) stromal cells are committed to lymphoid stromal differentiation, in agreement with their contact with TNF-expressing malignant B cells, Tfh, and tumor-associated neutrophils (TAN), and they overexpress CCL2 and IL-8, thus more efficiently recruiting TAM and TAN. FL stromal cells are involved in malignant B-cell recruitment and survival through the release of chemokines and hedgehog (Hh) ligands.

Direct lymphoma-promoting signals

Cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) have been recognized as playing critical roles in tumor development and progression in various solid tumor models. CAFs organize a heterogeneous network of activated, reprogrammed myofibroblasts exhibiting a specific phenotype, proliferation rate, migration propensity, gene expression profile, and epigenetic features. Owing to the demonstration that the survival and drug resistance of FL B cells could be increased by coculture with stromal cells, FL CAFs have drawn more attention than their DLBCL counterparts. FL CAFs display phenotypic features of lymphoid stromal cells within invaded LN and BM.46 In agreement with this, stromal cells obtained from FL BM exhibit a specific gene expression profile, including enrichment for a lymphoid stromal signature associated with an increased capacity to sustain FL B-cell growth.47 BM and LN stromal cells have been shown to prevent spontaneous and drug-induced apoptosis of NHL B cells in vitro through several mechanisms,4,48,49 including the production of hedgehog (Hh) ligands; the induction of microRNA-181a and decrease of microRNA-548m in malignant B cells, leading to downregulation of the proapoptotic protein BIM and activation of a prosurvival c-MYC/HDAC6 loop; the activation of the NF-κB pathway through poorly characterized stimuli, including the release of B-cell activating factor (BAFF); and the upregulation of ABC transporters triggering multidrug resistance. Of note, even if DLBCL malignant B cells produce autocrine Hh ligands, thus contributing to their decreased stroma dependence, coculture of DLBCL with stromal cells further reinforces drug tolerance and NF-κB activation independently of NF-κB genetic alterations and at least in part through the release of Hh ligands and BAFF.50 Lymphoid stromal cell–derived chemokines, including CXCL13, CCL19/CCL21, and CXCL12, contribute to lymphoma B-cell homing and retention, and CXCL12 was recently shown to be specifically upregulated within LN and BM FL stromal cell niches.51 Of note, a majority of functional studies have been performed using stromal cells maintained in long-term in vitro cultures, and a detailed in situ/ex vivo characterization of FL and DLBCL CAFs is still lacking.

Myeloid cells are also a major component of FL/DLBCL cell niches. FL-TAMs overexpress and transpresent IL-15 and collaborate with CD40L-expressing FL-Tfh to trigger STAT5 activation and FL B-cell growth.52 In DLBCL, BAFF was proposed as another monocyte-derived survival factor.53 In addition, DLBCL B cells were shown to produce IL-8 and to recruit APRIL-expressing neutrophils able in turn to protect them from spontaneous cell death in vitro.54 Conversely, direct contact with neutrophils was not sufficient to rescue primary FL B cells from apoptosis.55 Importantly, FL-TAM were recently proposed to be involved in FL B-cell receptor (BCR) activation. Specifically, although less than 25% of FL BCRs are supposed to be self-reactive, the FL BCR is characterized in most, if not all, FL cases by the introduction and positive selection of N-glycosylation sites in the variable region of immunoglobulin genes.56 The acquisition of these specific sequence motifs, which are very rare in normal B cells, is an early genetic event in FL pathogenesis, but it does not provide any B-cell–intrinsic advantage to malignant cells. Surprisingly, the glycan chains added to these sites, conversely to glycans of the Fc region of the same molecules, unusually terminate in a high mannose level, allowing interaction with DC-SIGNpos FL-TAMs that triggers universal long-lasting BCR aggregation and activation.57 This process supports FL B-cell survival in vitro and could be abrogated by pharmacologic BCR inhibitors. In DLBCL, no role for cells of the microenvironment has been proposed in BCR crosslinking. In ABC DLBCL, some recurrent genetic alterations, such as mutations in CARD11, provide autonomy from external BCR signal. Conversely, mutations affecting CD79A/CD79B increase the amplitude of the external BCR activation, potentially initiated by self-antigen recognition, thus contributing to an antigen-dependent chronic BCR signaling.58 Conversely, GC-DLBCL use an antigen-independent tonic BCR signaling.

In summary, the FL microenvironment is heavily enriched for CD4pos T cells displaying phenotypic and transcriptomic features of Tfh cells, the specialized T-cell subset involved in high-affinity GC B-cell selection, amplification, and differentiation.10 Importantly, Tfh are virtually absent from the DLBCL cell niche. FL-Tfh are characterized by unique gene expression and cytokine secretion profiles, partly explained by the amplification of a CD10-expressing Tfh subset able to directly sustain FL B-cell survival, in particular through IL-4 and CD40L signals.59 As discussed above, CD40L signaling also confers IL-15 sensitivity to B cells through induction of STAT5 expression and activation and thus cooperates with FL-TAM to support FL cell growth.52 Collectively, these studies demonstrate that the B-NHL–supportive microenvironment is made up of a specific combination of stromal cell, myeloid cell, and CD4pos T cell subsets.

Mechanisms of tumor-supporting cell polarization and activation

The mechanisms underlying supportive microenvironment recruitment, amplification, and commitment are a matter of intense interest because they could provide relevant new therapeutic targets. Malignant B cells themselves can endow their surrounding niche with supportive properties through a dynamic reciprocal activation program. In particular, loss-of-function alterations of TNFRSF14/HVEM in FL have been shown to trigger both B-cell autonomous activation, in cooperation with BCR signaling, and B-cell extrinsic activation of the lymphoma microenvironment.29 In an FL mouse model based on the simultaneous deregulation of BCL2 and inactivation of HVEM, Tfh, which express very high levels of the HVEM inhibitory receptor BTLA, were amplified and produced higher amounts of IL-4, tumor necrosis factor (TNF), and lymphotoxin (LT). Interestingly, patients with FL displaying HVEM inactivation exhibit increased Tfh infiltration and IL-4–dependent STAT6 phosphorylation in situ, thus validating the impact of HVEM genetic alteration on the composition of the tumor microenvironment. TNF and LT, the two nonredundant factors involved in lymphoid stromal differentiation and maintenance, were also upregulated in malignant B cells in HVEM-deficient mice, and lymphoid stromal cells, known to trigger FL B-cell survival, were overactivated. In agreement with this, primary human FL B cells contribute in a TNF-dependent manner to the differentiation of lymphoid stromal cells and to their higher secretion of CCL2 and IL-8.47,55 However, neither coculture with malignant B cells nor treatment with TNF is able to upregulate CXCL12 in human stromal cells,51 raising the question of the other mechanisms involved in FL stroma polarization.

As discussed previously, FL Tfh are characterized by an upregulation of IL-4, TNF, and LT compared with Tfh obtained from reactive tonsils.10 Interestingly, these three molecules affect stromal cell phenotype. IL-4, as well as FL-Tfh themselves, was recently highlighted as a CXCL12 inducer in stromal precursors and lymphoid stromal cells.51 Of note, stromal cells were also proposed to support the viability of FL-Tfh even if the role of lymphoid stroma in Tfh activation and functional heterogeneity remains to be explored.60 Tfh-derived IL-4 also contributes indirectly to FL pathogenesis through the upregulation of DC-SIGN on macrophages and immunoglobulin M on FL B cells, thus favoring the TAM–malignant cell crosstalk.57

In summary, besides their direct B-cell supportive effects, stromal cells also contribute to the polarization and organization of the FL microenvironment. In particular, FL stromal cells can recruit and interact with innate immune cells, including monocytes and neutrophils, through overexpression of CCL2 and IL-8.47,55 In agreement with this, these two chemokines are overexpressed in FL-invaded BM compared with normal BM. Interestingly, FL MSC protect recruited neutrophils from apoptosis and convert recruited monocytes into proangiogenic and anti-inflammatory TAM-like cells.47,55 Both tumor-associated neutrophils and TAM cooperate then with stromal cells to trigger FL B-cell survival.

Conclusions and perspectives

With the introduction of next-generation sequencing, the genetic landscape of B-NHL has rapidly been unraveled in recent years, thus placing a spotlight on the role of these genetic alterations in lymphomagenesis. However, the microenvironment emerges now as a key determinant of lymphoma development and evolution. In addition, progressive identification of pro- and antitumoral signals delivered by the dynamic cell network surrounding malignant B cells has paved the way for new therapeutic approaches aimed at improving the function of immune effector cells and/or disrupting the crosstalk between tumor cells and their supportive niche. The general lack of description of the heterogeneity of microenvironment subsets will be solved rapidly by the development of single-cell strategies, including mass cytometry (cytometry by time of flight [CyTOF]) and RNA-sequencing approaches as well as an exhaustive T-cell receptor repertoire. However, new questions emerge. First, the roles of extracellular matrix components, mechanical properties, and niche microarchitecture have not been fully appreciated. Second, after deciphering differences between microenvironment composition depending on lymphoma subtypes, lymphoma patients, and lymphoma localizations, the dissection of intratumoral heterogeneity also emerges as an important facet of the understanding of the B-NHL niche in the search for for spatial segregation of immune and stromal cells into discrete functional zones sustaining B-NHL proliferation or cancer progenitor cell maintenance. Finally, the mechanisms of B-cell–microenvironment crosstalk remain elusive, and the role of extracellular vesicular exchanges, as well as the impact of genetic alterations on niche composition and conversely the role of the pro- and antitumoral microenvironment on the selection of malignant B-cell subclones, have just started to be studied. The biggest roadblock to resolving these issues is the inadequacy of testing models. The development of new tools, including histocytometry on whole tissues, 3D tumor organoids mixing various cell subsets, or relevant lymphoma mouse models mimicking genetic events and microenvironment organization, will be mandatory to better understand B-NHL pathogenesis and to test new drug efficacy and mechanisms of action.

Correspondence

Karin Tarte, INSERM, UMR U1236, Faculté de Médecine, Université de Rennes 1, 2 Avenue du Professeur Léon Bernard, F-35043 Rennes, France; e-mail: karin.tarte@univ-rennes1.fr.

References

Competing Interests

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The author has received research funding from Celgene and Novimmune and has consulted for Celgene and Roche.

Author notes

Off-label drug use: None disclosed.