Abstract

Although the therapy of chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) has changed rapidly over the last 5 years, the key considerations in selecting a therapy for a previously treated patient with CLL continue to include the nature of the prior therapy and the duration of prior remission to that therapy, the prognostic features of the disease, and the health and comorbidities of the patient in question. For patients treated initially with chemoimmunotherapy, randomized trials have demonstrated the benefit of targeted therapy. Retrospective data suggest that ibrutinib is preferred as a first kinase inhibitor, whereas recent data with venetoclax and rituximab may challenge the choice of ibrutinib as a first novel agent in the relapsed setting. Data on sequencing of novel agents remain quite sparse, consisting of 1 prospective trial that demonstrated the efficacy of venetoclax in patients who have experienced progression with a kinase inhibitor, as well as a retrospective real-world analysis supporting this observation. Novel agents in advanced clinical development include primarily next-generation Bruton’s tyrosine kinase and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase δ inhibitors, with other classes still in phase 1 trials. Clinical trials of combination time-limited therapies with the goal of deep remission and discontinuation are also in progress.

Learning Objectives

Understand the data supporting the use of ibrutinib, idelalisib plus rituximab, and venetoclax plus rituximab in relapsed CLL

Describe the unique considerations in choosing subsequent therapy for patients previously exposed to ibrutinib

Introduction

In the last 5 years, chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) therapy has undergone a revolution, with the initial approvals of ibrutinib, idelalisib with rituximab, and venetoclax, followed by the increasing use of ibrutinib as frontline therapy after that approval in March 2016. However, with the advent of more therapeutic options in both the frontline and relapsed settings, the decision-making process in choosing a therapy for a patient with relapsed CLL has become more complicated. Therefore, this article will separately address the data as well as practical considerations in the management of patients treated only with prior chemoimmunotherapy (CIT) vs those treated with prior ibrutinib. The shift toward first-line targeted therapy with ibrutinib will increasingly alter the management of relapsed CLL; however many critical questions arising from this shift remain not only unanswered but almost unexplored. Furthermore, what little we know about sequencing novel agents is mostly based on the historical timing of their availability, with no actual data on what might be the optimal approach. In fact, the optimal approach may ultimately involve novel agents or combination therapies still in development, which I will also discuss before concluding with some theoretical concerns about the future of CLL therapy.

Prior therapy

CIT

Previously treated patients who have received only prior CIT are perhaps the simplest group to address, because most of the early clinical trials of novel agents enrolled only this group. The initial approval of the first-in-class covalent Bruton’s tyrosine kinase (BTK) inhibitor ibrutinib was in patients with relapsed CLL who had received at least 1 prior therapy, based on early results of a single-arm study1 that has now reported 5-year follow-up results,2 with an overall response rate (ORR) of 89% and median progression-free survival (PFS) of 51 months in heavily pretreated patients with high-risk disease. In this study, PFS was shorter among patients with 17p deletion [del(17p)], at 26 months, and among those with complex karyotype, at 31 months. The confirmatory RESONATE trial randomized patients with relapsed CLL to ibrutinib or ofatumumab and demonstrated early PFS and overall survival (OS) benefits.3 This study has now been reported with 4-year follow-up demonstrating a 59% 3-year PFS in the ibrutinib arm,4 with substantial benefit in all subgroups of disease and no difference based on mutated vs unmutated IGHV. At present follow-up, no difference in PFS is seen in patients with del(17p) alone, although patients with both del(17p) and TP53 mutation showed reduced PFS compared with those with neither at 2-year follow-up.5 Furthermore, an analysis of 243 relapsed patients with del(17p) treated with ibrutinib demonstrated a 55% PFS at 30 months, worse in those with coexisting complex karyotype.6 These findings demonstrate that outcomes of patients with del(17p) CLL likely remain worse even with ibrutinib therapy, despite its marked efficacy, and underscore the importance of testing for del(17p) at each relapse, as well as determining genomic complexity with stimulated karyotype.

These efficacy data have rapidly established ibrutinib as standard of care for most if not all patients with relapsed CLL. Studies have explored combinations with other standard therapies. An MD Anderson Cancer Center randomized trial comparing ibrutinib with ibrutinib plus rituximab found that the latter resulted in more rapid response through clearance of lymphocytosis but provided no benefit in PFS or OS.7 Combining ibrutinib with obinutuzumab might seem more promising, given that obinutuzumab extended PFS compared with rituximab when combined with chlorambucil,8 and given that in vitro at least, obinutuzumab can partially overcome ibrutinib inhibition (through interleukin-2–inducible kinase [ITK]) of natural killer cell–mediated antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity. Thus far, the rate of complete response (CR) among patients with relapsed or refractory CLL receiving a BTK inhibitor has not been markedly increased with obinutuzumab in 2 studies, at 8% and 12%, suggesting that a large benefit in PFS is unlikely with longer follow-up.9,10 Another novel anti-CD20 antibody engineered to increase antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity is ublituximab, which when added to ibrutinib in the GENUINE trial increased the ORR to 78% from 45%, among patients with TP53 dysfunctional or del(11q) relapsed disease. However, the CR rate was only 7%, and no difference in PFS was seen.11 The HELIOS study compared bendamustine plus rituximab (BR) with BR plus ibrutinib followed by continuous ibrutinib maintenance and found a marked PFS benefit with the addition of continuous ibrutinib, despite a relatively minor early increase in CR and rates of undetectable minimal residual disease (MRD).12 Over time, the rates of CR and undetectable MRD have steadily risen, with a trend toward a benefit for OS.13 However, how well these end points translate to improved long-term benefit in patients still receiving ibrutinib remains unknown. BR plus ibrutinib has not come into widespread use, likely in part because of a desire to avoid CIT and in part because it is unclear whether BR plus ibrutinib results in better PFS than ibrutinib alone, because the HELIOS study did not have an ibrutinib-alone arm. Therefore, at present in the relapsed setting, the data support using ibrutinib as a single agent rather than with an antibody or CIT, except in unusual circumstances.

The recently reported MURANO trial may challenge the primacy of ibrutinib as first novel agent in the relapsed setting.14 In MURANO, patients with CLL with a median of 1 prior CIT were randomized between venetoclax rituximab and BR. Venetoclax was administered for 2 years with 6 months of rituximab and then stopped. With a median follow-up of 23.8 months, the study showed a marked improvement in PFS for venetoclax plus rituximab, with an estimated 2-year PFS of 85% compared with 36% for BR.14 Toxicity was manageable, with 6 (3.1%) of 194 patients receiving venetoclax plus rituximab experiencing grade 3 or 4 tumor lysis, only 1 of which was clinical. These results are impressive, but it is important to note that with current follow-up, too few patients have been observed for >2 years to determine the durability of response after discontinuation. However, this planned discontinuation at 2 years is a compelling advantage of venetoclax plus rituximab compared with indefinite ibrutinib. Thus, the recent US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval of venetoclax plus rituximab makes it the first time-limited novel agent regimen in CLL, which will likely be of great interest to patients, assuming the responses are durable. Despite the benefits of a time-limited regimen, factors complicating the decision to use venetoclax plus rituximab before ibrutinib include the still short follow-up with venetoclax regimens and the limited data on the efficacy of ibrutinib after venetoclax. The only data addressing the latter question come from an Australian report on outcomes among heavily pretreated patients who discontinued venetoclax; 6 of 8 patients who experienced CLL progression were treated with ibrutinib, and 5 responded, although only 3 were still alive with short follow-up.15 Two died as a result of toxicity and 1 as a result of progressive disease. Four patients who had experienced progression with Richter’s transformation (RT) and responded to salvage treatment went on to receive BTK inhibitors for subsequent CLL relapse and remain alive, 3 for >3 years posttransformation.15

The third novel agent approved for relapsed/refractory CLL is idelalisib, which was approved in combination with rituximab for previously treated patients with CLL with comorbidities such that rituximab would be an appropriate therapy. In phase 1, idelalisib showed a median PFS of 32 months among patients treated at the recommended phase 2 dose of ≥150 mg twice daily.16 Its first registration trial enrolled patients with CLL with short first remission who were not appropriate for cytotoxic therapy and randomized them between idelalisib plus rituximab and placebo plus rituximab.17 The patient population had a median age of 71 years and median comorbidity (Cumulative Illness Rating Scale) score of 8, and 44% had del(17p). Idelalisib plus rituximab markedly improved ORR, PFS, and OS, ultimately showing a median PFS of 19.4 months, which was not different based on del(17p) or IGHV mutation status.18 Two subsequent registration trials, combining idelalisib with ofatumumab19 and idelalisib with BR,20 have shown similar results. Despite high efficacy, idelalisib has typically been reserved for later-line therapy because of adverse effects that include both bacterial and opportunistic infections, as well as autoimmune colitis, pneumonitis, and hepatitis that can be severe and are worse in younger, less heavily pretreated patients.21,22 A retrospective analysis also suggested that patients receiving ibrutinib as a first kinase inhibitor did better than those who received idelalisib as a first kinase inhibitor.23

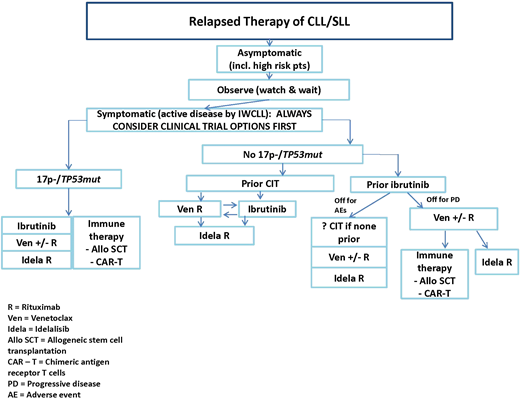

Table 1 provides a summary of considerations in choosing a first novel agent, including comorbidities and drug interactions, and Figure 1 provides a summary flowchart.

Considerations in choosing a targeted therapy

| . | Favors . | Relative contraindications . | Drug interactions . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ibrutinib | Longest follow-up of PFS to date | High bleeding risk including lack of data with platelets <30 × 109/L | Anticoagulants (avoid if possible, especially warfarin; if necessary, use NOACs) |

| Nodal predominant disease has rapid response; cytopenias can be slower to resolve | Cardiac disease | Avoid dual antiplatelet therapy | |

| Active infection, especially fungal | Strong CYP3A inhibitors: generally avoid, but can use higher-dose posaconazole if ibrutinib dose is reduced to 70 mg daily | ||

| Difficult to control hypertension or atrial fibrillation | Moderate CYP3A inhibitors or voriconazole: reduce ibrutinib dose to 140 mg daily | ||

| Active autoimmunity can show early flare before achieving longer-term control | |||

| Not studied in patients with comorbidities; recent study suggests worse outcomes58 | |||

| Hepatic disease* | |||

| Venetoclax (± rituximab) | Extremely effective in bone marrow clearance, with potential to achieve MRD negativity rarely seen with kinase inhibitors; allows more easily for fixed-duration therapy | Renal failure | Strong CYP3A inhibitors: avoid during escalation, later 75% dose reduction |

| Spontaneous tumor lysis | |||

| Possibly safer than kinase inhibitors with active infection (eg, fungal) | Cytopenias, particularly neutropenia, resulting from hypocellular bone marrow or myeloid disorder | Moderate CYP3A inhibitor or P-gp inhibitors: avoid during escalation; later, 50% dose reduction | |

| Possibly safer in setting of active autoimmunity | No contraindication to anticoagulation in general, but will increase serum warfarin concentration | ||

| Difficulty tolerating a fluid load for dose escalation | |||

| Idelalisib + rituximab | Nodal predominant disease has rapid response; cytopenias can be slower to resolve | Adverse effect profile can be more challenging but is likely better in older patients with multiple prior therapies (particularly CIT) | Strong inhibitor of CYP3A4 itself; avoid combining with CYP3A4 substrates (including venetoclax) |

| Not contraindicated in cardiac or renal disease | Hepatic disease* | ||

| Registration trial enrolled patients with high level of medical comorbidities17 | Inflammatory bowel disease | ||

| RT less commonly reported at relapse than with ibrutinib or venetoclax | Active autoimmunity | ||

| Active infection† |

| . | Favors . | Relative contraindications . | Drug interactions . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ibrutinib | Longest follow-up of PFS to date | High bleeding risk including lack of data with platelets <30 × 109/L | Anticoagulants (avoid if possible, especially warfarin; if necessary, use NOACs) |

| Nodal predominant disease has rapid response; cytopenias can be slower to resolve | Cardiac disease | Avoid dual antiplatelet therapy | |

| Active infection, especially fungal | Strong CYP3A inhibitors: generally avoid, but can use higher-dose posaconazole if ibrutinib dose is reduced to 70 mg daily | ||

| Difficult to control hypertension or atrial fibrillation | Moderate CYP3A inhibitors or voriconazole: reduce ibrutinib dose to 140 mg daily | ||

| Active autoimmunity can show early flare before achieving longer-term control | |||

| Not studied in patients with comorbidities; recent study suggests worse outcomes58 | |||

| Hepatic disease* | |||

| Venetoclax (± rituximab) | Extremely effective in bone marrow clearance, with potential to achieve MRD negativity rarely seen with kinase inhibitors; allows more easily for fixed-duration therapy | Renal failure | Strong CYP3A inhibitors: avoid during escalation, later 75% dose reduction |

| Spontaneous tumor lysis | |||

| Possibly safer than kinase inhibitors with active infection (eg, fungal) | Cytopenias, particularly neutropenia, resulting from hypocellular bone marrow or myeloid disorder | Moderate CYP3A inhibitor or P-gp inhibitors: avoid during escalation; later, 50% dose reduction | |

| Possibly safer in setting of active autoimmunity | No contraindication to anticoagulation in general, but will increase serum warfarin concentration | ||

| Difficulty tolerating a fluid load for dose escalation | |||

| Idelalisib + rituximab | Nodal predominant disease has rapid response; cytopenias can be slower to resolve | Adverse effect profile can be more challenging but is likely better in older patients with multiple prior therapies (particularly CIT) | Strong inhibitor of CYP3A4 itself; avoid combining with CYP3A4 substrates (including venetoclax) |

| Not contraindicated in cardiac or renal disease | Hepatic disease* | ||

| Registration trial enrolled patients with high level of medical comorbidities17 | Inflammatory bowel disease | ||

| RT less commonly reported at relapse than with ibrutinib or venetoclax | Active autoimmunity | ||

| Active infection† |

NOAC, non–vitamin K oral anticoagulants.

Screen all patients on any of these drugs for hepatitis B and C, and treat if found.

In the relapsed setting, my practice is to recommend prophylaxis against Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia and against varicella zoster virus for all patients with CLL. This recommendation is stronger with idelalisib plus rituximab.

The choice between venetoclax (ven) plus rituximab (R) and ibrutinib depends on medical factors outlined in Table 1, as well as considerations that include: longer-term follow-up data with ibrutinib at present, good data on ven response after progression with ibrutinib compared with few data on the reverse, potential for time-limited therapy with ven vs indefinite therapy with ibrutinib, more intense monitoring early on for ven, fewer long-term adverse effects with ven, and patient preference. AE, adverse event; alloSCT, allogeneic stem-cell transplantation; CAR-T, chimeric antigen receptor T cell; idela, idelalisib; IWCLL, International Workshop on Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia; PD, progressive disease.

The choice between venetoclax (ven) plus rituximab (R) and ibrutinib depends on medical factors outlined in Table 1, as well as considerations that include: longer-term follow-up data with ibrutinib at present, good data on ven response after progression with ibrutinib compared with few data on the reverse, potential for time-limited therapy with ven vs indefinite therapy with ibrutinib, more intense monitoring early on for ven, fewer long-term adverse effects with ven, and patient preference. AE, adverse event; alloSCT, allogeneic stem-cell transplantation; CAR-T, chimeric antigen receptor T cell; idela, idelalisib; IWCLL, International Workshop on Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia; PD, progressive disease.

Should any patient receive later-line CIT in the ibrutinib era?

This question has arisen because of the efficacy of ibrutinib and the toxicity of multiple courses of CIT. Furthermore, analysis of the RESONATE trial has suggested that PFS is better when ibrutinib is administered second line compared with later line, although these data come from a high-risk patient population.4,5 Initiation of ibrutinib comes with a number of negatives, including the need for continuous indefinite therapy, the significant AE profile, and the cost. Therefore, patients who have had a long duration of response to prior CIT may prefer a short course of repeat CIT with potential for long remission off therapy, compared with committing to indefinite ibrutinib. As in the preibrutinib era, it is likely that truly low-risk patients can do well with repeat CIT. However, the more definitively the patient is determined to be low risk, the better. Before considering this as an option for a patient, I would obtain repeat fluorescence in situ hybridization and karyotype analysis as well as TP53 somatic mutation testing at an absolute minimum. Only in patients without del(17p), TP53 mutation, del(11q), or a complex karyotype would I consider repeat CIT, given that CIT has limited efficacy in patients with these prognostic markers. Furthermore, given the association of increased genomic complexity with unmutated IGHV24 and the ensuing greater likelihood of acquiring adverse genetic features during repeat CIT, I would also prefer that patients considering repeat CIT have mutated IGHV. Thus, in carefully selected cases with molecular profiling and long prior remission (at least 3-5 years), as well as patient preference, I would be willing to consider repeat CIT. However, in this context, it is important to note that we now have data showing that adding either idelalisib or ibrutinib to BR certainly improves PFS and possibly OS12,20 in unselected relapsed patients, raising the question of whether patients considering repeat CIT should have a novel agent added as well if possible. Whether these data might shift in a carefully selected low-risk patient population is unknown.

Ibrutinib

Patients whose prior therapy was ibrutinib need to be considered separately because of data suggesting that they may have a different, more aggressive disease biology and because of the still limited data on therapy after ibrutinib. Early data on outcomes of heavily pretreated patients who discontinued ibrutinib in the setting of progression suggested that they had poor OS,25,26 probably because discontinuation of ibrutinib in the setting of progressive disease was associated with a marked tumor flare that could be difficult to control. More recent data have demonstrated better but still relatively poor survival.27 A subset of these patients also develop RT, which is more common in the first 1 to 2 years of ibrutinib therapy.27 A recent analysis focused on 167 patients whose disease was progressing with ibrutinib or idelalisib and who underwent positron emission tomography/computed tomography scanning as part of screening for a venetoclax clinical trial.28 Biopsy was required if maximum standardized uptake value was ≥10 or 4 to 10 in patients with high-risk markers with at least one of the following: any B symptoms, elevated lactate dehydrogenase, or a node >5 cm. Thirty-five patients ultimately underwent biopsy, with 23% found to have RT, and 71% still had CLL.28 No clear clinical or positron emission tomography predictor was identified indicating patients found to have RT, but patients with maximum standardized uptake value of ≥10 had poorer PFS with venetoclax (15.4 vs 24.7 months), despite a comparable ORR.28 The patients in all of these reports had disease that was heavily pretreated and enriched for high-risk cytogenetics, and it is possible that patients with fewer prior therapies or fewer high-risk markers may not have such an aggressive course at time of progression; however, as yet this remains unknown, and it is critical to address because ibrutinib therapy is moving earlier in the disease course. Alternatively, it is also possible that the recurrent mutations associated with progression with ibrutinib, specifically BTK Cys481X and activating mutations in PLCG2, may actually have more aggressive disease biology, in which case outcomes will be poor with relapse even in earlier lines of therapy. Current management of patients whose disease is progressing with ibrutinib typically includes continuing ibrutinib right up until the initiation of a subsequent therapy, or even overlapping with the next therapy, to avoid the tumor flare seen early on, which can be explosive. High-dose methylprednisolone regimens can also be useful as bridging therapy in this setting.

The only reasonably large prospective clinical trial in this patient population looked at single-agent venetoclax in patients whose disease was progressing with ibrutinib or idelalisib.29,30 Tumor lysis was manageable, although some patients with aggressive disease required a more rapid inpatient dose escalation to achieve therapeutic levels of venetoclax more quickly. In the postibrutinib cohort, venetoclax had a high ORR of 65%, but CR/CR with incomplete count recovery was only 9%, and the median PFS was 24.7 months.30 Although this trial clearly suggests that most patients will respond to venetoclax after their disease progresses with ibrutinib, the low CR rate is concerning in comparison with other venetoclax studies, in which the high rates of CR and/or undetectable MRD were strongly associated with durability of response.31 Therefore, patients whose disease has progressed with ibrutinib often have aggressive disease and have only 1 well-characterized treatment option with venetoclax. Although they can also receive a phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase δ (PI3Kδ) inhibitor like idelalisib, the data for activity of PI3K inhibitors in this setting are limited. Five patients received the PI3Kγ,δ inhibitor duvelisib in its phase 1 study, with 2 nodal responses among 5 patients, with 1 partial response (PR).32 A retrospective study also found that patients who stopped ibrutinib for progression had better outcomes with venetoclax than with alternative kinase inhibitors.23 Thus, the population of patients whose disease has progressed with ibrutinib represents a new population of unmet need, with limited standard treatment options and with whom I discuss more definitive therapeutic options of immune-based therapy, including reduced-intensity alloSCT or investigational trials of chimeric antigen receptor T cells. This approach applies even to patients for whom ibrutinib is first-line therapy, if their disease has progressed during active ibrutinib therapy. This view is supported by a recent European guideline on the evolving definition of high-risk CLL and the timing of alloSCT.33 The optimal timing of these immune-based approaches remains complicated and individualized, as discussed recently in an expert opinion paper,34 particularly among patients who achieve a deep response with their second novel agent. Despite its promise, chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy has thus far had lower complete remission rates in CLL than in other B-cell diseases and remains investigational; whether it could eventually replace alloSCT remains unclear.

But what about patients who discontinue ibrutinib for an AE? Although the rate of discontinuation for AEs reported from clinical trials in relapsed patients ranges from 12%4 to 25%27 at 4-year follow-up, a real-world analysis of >600 patients reported a 42% discontinuation rate with 17-month follow-up, primarily because of AEs that included arthralgia, bleeding, infection, and atrial fibrillation.35 Therefore, this is a common problem, currently more common than patients experiencing progression with ibrutinib. How should these patients be managed? First, I would not treat them until their disease again progresses to the point of requiring therapy by International Workshop on Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia criteria, which may be some time. Second, for a previously untreated patient without del(17p) or TP53 mutation who received only short-duration ibrutinib, it is reasonable to consider CIT, but again, the data showing that CIT has efficacy in this setting are limited. In a retrospective study of patients with a median of 2 prior regimens before ibrutinib, the response to CIT among patients stopping ibrutinib was quite poor, but again, these patients had undergone prior CIT, and many had high-risk cytogenetics.23 For patients who are CIT naïve, do not have del(17p) or TP53 mutation, and discontinue frontline ibrutinib for an AE, CIT is a reasonable therapeutic option, albeit without any described outcomes. For patients who have undergone prior CIT, particularly with short remissions, and/or have high-risk cytogenetics, further CIT is unlikely to be of benefit. The retrospective data analysis of >600 mostly nontrial patients suggests that patients stopping a kinase inhibitor for an AE can experience prolonged benefit from another kinase inhibitor, as well as from venetoclax, so in this setting, it is reasonable to try an alternative kinase inhibitor before proceeding to venetoclax.23,36

Novel agents in development

BTK inhibitors

Given the success of inhibitors of BTK, PI3Kδ, and BCL-2, many new drugs against the same targets are in development. The novel BTK inhibitors come in 2 categories; the first includes covalent inhibitors that bind to Cys481 like ibrutinib but are more specific for BTK, and the second includes noncovalent reversible inhibitors of variable selectivity for BTK that target both wild-type and Cys481X-mutant BTK.

The BTK inhibitors that are more specific and covalent include acalabrutinib, zanubrutinib (BGB-3111), and tirabrutinib (GS-4059). Acalabrutinib potently inhibits BTK and has no physiologically relevant activity against ITK or epidermal growth factor receptor and much reduced activity against TEC, which should reduce bleeding risk.37 The phase 1b/2 data with acalabrutinib in patients with relapsed or refractory CLL were recently updated with 19.8-month follow-up, demonstrating an 87% ORR and 18-month PFS estimated at 90%. Only in the complex karyotype subgroup was the median PFS reached, at 28 months.38 These data seem approximately comparable to those on ibrutinib at a similar stage of development. Acalabrutinib received accelerated approval from the FDA in late 2017 for the therapy of mantle cell lymphoma, and 3 randomized registration trials are ongoing in CLL. Zanubrutinib is also a potent inhibitor of BTK that lacks activity against epidermal growth factor receptor or ITK, but it does inhibit TEC similarly to ibrutinib. The pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic profile of zanubrutinib has been carefully optimized for sustained BTK occupancy not just in plasma but also in lymph nodes, and its pharmacokinetic profile is such that free drug exposure is sustained in plasma for an extended time.39 In the phase 1 study, 69 patients with CLL/small lymphocytic lymphoma (SLL) were treated, 18 of whom were treatment naïve. Del(17p) was seen in 39% and del(11q) in 32%. With a median follow-up of 12.3 months, the ORR was 94%, with a 3% CR rate.39 Registration trials of zanubrutinib were recently initiated. Finally, long-term follow-up of the phase 1 study of tirabrutinib was recently reported and demonstrated a 96% ORR, with median PFS of 38.5 months, in patients with relapsed or refractory CLL. Its planned registration path is not clear. For all 3 of these drugs, the number of patients treated is too few and/or the follow-up too short to know for certain how efficacy and tolerability compare with those of ibrutinib. It has been suggested that their increased specificity for BTK may result in fewer adverse effects. One each of the acalabrutinib and zanubrutinib registration trials is a head-to-head trial against ibrutinib, which will certainly help shed light on this question.

The second category of novel BTK inhibitor includes noncovalent inhibitors that are designed to be effective against both wild-type and Cys481-mutated CLLs. Many such drugs are in preclinical development, and 2 of them, SNS-062 (now called vecabrutinib) and ARQ531, are currently in phase 1 trials in patients with relapsed or refractory hematologic malignancies, including CLL.

PI3Kδ inhibitors

Given the value of PI3Kδ as a target and the efficacy of idelalisib, many novel PI3K inhibitors are also in clinical development in CLL, with both duvelisib and umbralisib in registration trials. Duvelisib is a potent and specific inhibitor of both the δ and γ isoforms of PI3K, which allows for dual targeting of CLL cells through inhibition of δ and of the myeloid and T cells in the microenvironment through inhibition of γ. In the phase 1 study, the maximum tolerated dose was determined to be 75 mg twice daily, but the dose taken forward in CLL was 25 mg twice daily, which was equally effective and is continuously above the 90% inhibitory concentration for δ, with ∼50% inhibition of γ.39 The ORR in CLL (not including PRs with lymphocytosis) was 56%, with 1 CR.40 The results of the randomized registration trial DUO were reported at the American Society of Hematology meeting in 201741 ; 319 patients were randomized 1:1 to duvelisib 25 mg twice daily or ofatumumab as per the label for relapsed CLL. The patients had a median of 2 prior therapies, and characteristics were well balanced in the 2 arms. Duvelisib significantly extended PFS compared with ofatumumab to a median 13.3 months per independent review committee and 17.6 months per investigator, including in del(17p) patients.41 Infectious and autoimmune toxicities were seen but infrequently led to discontinuation. The FDA has accepted the duvelisib new drug application for priority review with a Prescription Drug User Fee Act date in early October 2018.

The other PI3Kδ inhibitor in advanced clinical development in CLL is umbralisib. Umbralisib is a less potent but more specific PI3Kδ inhibitor42 that also has activity against casein kinase 1ε,43 which has recently been shown to be a therapeutic target in CLL.44 No pharmacodynamic data are available as yet from treated patients, making it hard to know how these targets interact in vivo. During the phase 1 study in hematologic malignancies, the drug was reformulated for better absorption, and the RP2D was 800 mg daily of the micronized formulation, taken in a fed state.45 Twenty-four patients with CLL with a median of 3 prior therapies were treated, with 20 assessed for efficacy after receiving higher doses. The ORR was 50% PRs plus an additional 35% PR rate with lymphocytosis; the median duration of response was 13.4 months.45 The most common AEs were diarrhea, nausea, and fatigue, although these were mostly low grade.45 A combined analysis of 336 patients treated in multiple mostly combination studies with umbralisib for a median of 5 months of exposure identified rates of grade 3 to 4 diarrhea of only 4% and grade 3 to 4 transaminitis of <3%.46 Although these data suggest a different safety profile compared with other PI3Kδ inhibitors, the follow-up is still quite short, which limits the interpretation of the data, particularly for diarrhea and colitis. The UNITY registration trial comparing umbralisib together with the novel anti-CD20 antibody ublituximab with obinutuzumab chlorambucil in mixed untreated and relapsed CLL patients has completed enrollment.

A variety of other selective PI3Kδ inhibitors are in early phase 1 studies in CLL and lymphoma, including INCB050465 and ME-401.

Other novel agents

Other categories of novel agents are also in earlier clinical development in CLL/SLL. Also inhibiting the BCR pathway are the SYK inhibitors, led by entospletinib, which has been studied in a phase 2 trial in patients with CLL and non-Hodgkin lymphoma previously treated with BTK or PI3K inhibitors. In this challenging setting, the ORR was 26%, with PFS of ∼6 months.47 The drug is in multiple combination studies, but its future development path is not yet clear. Cerdulatinib, a combination SYK/JAK inhibitor, has demonstrated preclinical activity in ibrutinib-resistant CLLs48-50 and is currently in a phase 1 study. Although lenalidomide has significant activity in CLL, with 2 randomized trials demonstrating markedly improved PFS in a post-CIT maintenance setting, it is not moving toward registration in CLL. Instead, a next-generation immunomodulatory drug (IMiD) called CC-122 is currently in phase 1 trials as a single agent or in combination with obinutuzumab or ibrutinib in CLL and lymphoma. Finally, cirmtuzumab is a humanized monoclonal antibody specific for ROR1, a Wnt5a cell-surface receptor that is ubiquitously and uniquely expressed in CLL. In phase 1, cirmtuzumab was found to be safe and to inhibit its target, with stable disease in most patients despite only 4 doses of antibody. This drug is now in a combination trial with ibrutinib.

Novel combinations in relapsed or refractory CLL

BTK and BCL2 inhibitors

Much interest has focused on the combination of ibrutinib and venetoclax, based both on in vitro data suggesting synergy51 and on a clinical rationale related to activity in lymph nodes vs bone marrow, respectively, and on nonoverlapping clinical toxicity. At the American Society of Hematology meeting in 2017, 2 trials of this combination in the relapsed setting were reported. MD Anderson presented data from a study in which ibrutinib was administered for 3 months before venetoclax escalation, with the latter administered for 2 years and ibrutinib administered indefinitely.52 Thirty-seven patients were enrolled, 92% of whom had at least 1 of the following: unmutated IGHV, del(17p), or del(11q). During early follow-up over the first year of therapy, a progressive increase in CR and undetectable bone marrow MRD was seen at the assessed 3-month intervals, reaching a 69% CR rate and 13% rate of undetectable MRD in bone marrow at 6 months.52 The second study, CLARITY, comes from the UK CLL Group and starts with 8 weeks of ibrutinib before venetoclax dose escalation.53 MRD is monitored in the bone marrow at 6, 12, and 24 months. Patients who have undetectable MRD are planned to discontinue ibrutinib and venetoclax after completing consolidation therapy of the same duration as the therapy required to achieve undetectable MRD. This latter plan is based on mathematical modeling targeted to drive residual disease low enough to allow prolonged remission off therapy. Thus far, 38 patients have reached their month-8 evaluation, with a 47% CR rate and 32% rate of undetectable MRD in bone marrow, again with improvement over successive evaluations.53 Finally, the 3-drug combination of ibrutinib, venetoclax, and obinutuzumab has been studied in phase 1 in the relapsed setting at The Ohio State University; all 3 drugs could be safely administered in combination at their full single agent–approved doses.54 The follow-up in all of these studies is extremely short, but the efficacy in terms of CR and achievement of undetectable MRD seems preliminarily encouraging.

BTK and PI3K inhibitors

Fewer combination data are available for ibrutinib with other kinase inhibitors, but ibrutinib has been combined with umbralisib (TGR-1202), with both drugs able to be administered at full dose and no dose-limiting toxicities observed.55 The study enrolled 32 patients with mantle cell lymphoma or CLL. The 18 patients with CLL had a median of 2 prior therapies, with 2 having received prior ibrutinib and 4 having received a prior PI3K inhibitor; 22% had del(17p) and 39% del(11q). The ORR was 94% with 1 CR, and 1-year PFS was 88%.55 A similar phase 1 study combined ibrutinib with umbralisib and ublituximab in patients with B-cell malignancies with a median of 3 prior regimens.56 Among 19 evaluable patients with CLL/SLL, all responded. With a median time on study of 11.1 months, 6 patients with CLL/SLL discontinued for progressive disease,56 although 6 CRs were also seen. Continued follow-up will be needed to further assess these regimens.

Other combinations

To date, less work has been done on other combinations. A cautionary note on the safety of combining kinase inhibitors arose from an early study that combined idelalisib with entospletinib using a rapid intrapatient dose escalation and observed an 18% incidence of severe treatment-emergent pneumonitis that led to 2 deaths.57 Therefore, a careful phase 1 dose escalation is clearly required for any novel combinations.

Summary

The marked recent progress in CLL therapy, with the approvals of ibrutinib, obinutuzumab, idelalisib, and venetoclax, has led to a bewildering array of options. The drugs have largely been developed as single agents administered continuously (or with an antibody), leading to the idea that they can be used sequentially. However, the use of sequential single agents facilitates the development of therapeutic resistance, and few data speak to the effectiveness of these agents in any sequence, much less to their optimal ordering. Current sequencing is primarily a result of historical availability rather than scientific rationale. More work on the biology of resistance, ideally in the context of prospective clinical trials studying sequential therapy, is desperately needed to provide rational guidance for the future. Similarly, a deeper understanding of biologic predictors of response to different novel agents, as well as deeper risk stratification of patients particularly in early-line clinical trials, is desperately needed.

The other larger question is whether the short-term use of combination therapy, with the goal of deep remission, might be preferable to continuous single agents, particularly in fitter patients with long life expectancy. Such combinations would save on toxicity and cost, allow potentially long times off therapy, and reduce the development of resistance through the use of 2 independent mechanisms of action followed by discontinuation. Despite these theoretical advantages, actually defining the best combinations, their best order and duration, and the patient population of interest remains challenging. In particular, when the single agents all have high response rates and several-year PFS, the choice of a short-term surrogate end point to select the most promising combination regimen is challenging. For combinations that include venetoclax, undetectable MRD is a reasonable and achievable end point that correlates with PFS.31 However, for combinations of kinase inhibitors, it is hard to know what would be an appropriate short-term surrogate end point to indicate efficacy, because undetectable MRD is probably unlikely, but the combination may still reduce the development of resistance. CR is an option, but its relation to improved PFS in this setting is yet to be shown. Any such combinations also need to be tolerable. This landscape is further complicated by the next-generation inhibitors that are soon coming to market, which are often more specific and thought to be better tolerated, making them ideal candidates for combination therapy. With this increasingly complicated landscape, the importance of well-designed comparative clinical trials with thoughtful correlative science and long-term follow-up has never been greater.

Correspondence

Jennifer R. Brown, Department of Medical Oncology, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, 450 Brookline Ave, Boston, MA 02215; e-mail: jennifer_brown@dfci.harvard.edu.

References

Competing Interests

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: J.R.B. has served as a consultant for Janssen, Pharmacyclics, AstraZeneca, Beigene, Sun, Loxo, Sunesis, Gilead, Verastem, TG Therapeutics, AbbVie, Genentech, Pfizer, Celgene, and Kite; has received an honorarium from Teva; receives research funding from Gilead, Sun, and Verastem; and serves on data safety monitoring boards for Morphosys and Invacs.

Author notes

Off-label drug use: Venetoclax was used for frontline therapy of CLL; multiple investigational drugs not approved for any indication were used.