Abstract

In the past decade, many new agents have been introduced for the management of follicular lymphoma, and therapeutic strategies have evolved over time. The clinical benefits of the different treatments vary and, at the time of progression, are influenced by patient and disease characteristics, the duration of the interval from last treatment, and the nature of the treatments previously administered. Altogether, this results in a marked heterogeneity of clinical situations encountered during the treatment of these patients. Despite numerous trials performed in the field, there is no single standard of care for patients undergoing second-line treatment or beyond. Furthermore, patients recruited in these studies have characteristics that rarely represent the full spectrum of possible clinical presentations. Therefore, to optimally individualize treatment, all of the risks (short- and long-term) and benefits of the available options should be well known. Discussing the goals of therapy with the patient at each intervention is also critical in providing an optimal sequence of therapy.

Learning Objectives

Describe the new agents or regimens available for patients with relapsed or refractory follicular lymphoma, their efficacy, and their side effects

Understand how the strategy chosen for the first line of therapy influences subsequent lines

Discuss the parameters to be considered for the different lines of therapy in order to improve outcomes without reducing the patient’s quality of life

Introduction

The life expectancy of patients with follicular lymphoma has substantially increased in the last 3 decades. For a significant proportion of patients, prolonged response can be achieved (≥10 years) without the need for additional treatment through the use of effective therapy, which often comprises a combination of an anti-CD20 antibody and chemotherapy (possibly consolidated by antibody maintenance).1 However, several points must be considered when one is discussing the sequence of therapy to achieve optimal treatment of patients with disease progression. First, this indolent disease can be asymptomatic for years, not only before therapy is initiated but also years later, even for some patients who have experienced several episodes of disease progression and have been exposed to multiple lines of therapy. This lack of symptoms might reflect the biological heterogeneity of this disease, with each clinical progression possibly emerging from related but divergent lymphoma clones.2 Therefore, disease progression does not necessarily warrant retreatment. Second, although the majority of patients with follicular lymphoma die of their disease, other causes of death, including treatment-related toxicities, are present.3 Avoiding treatment sequelae that will decrease the quality of life of these patients, or their life expectancy, is an important goal. Third, patients with histological transformation have a dramatic cumulative risk of lymphoma-related death, whereas patients without histological transformation have a lower risk of lymphoma-related death.

Therefore, when making therapeutic decisions for a patient presenting with follicular lymphoma, we should always weigh the benefits and risks of each available option and define the goals of therapy. Several parameters should be evaluated: the clinical need to initiate therapy, such as presence of disease-related symptoms or threat of organ function, Groupe d’Etude des Lymphomes Folliculaires criteria (Table 1), and pace of lymphoma growth; prognostic parameters that may help predict long-term outcomes; age and comorbidities; and the patient’s wishes and expectations.

Groupe d’Etude des Lymphomes Folliculaires criteria

| The presence of any 1 of these criteria defines a patient with a high tumor burden |

| A lymphoma tumor ≥7 cm in diameter* |

| Three nodes in 3 distinct areas, with each node ≥3 cm in diameter |

| Presence of systemic symptoms |

| Symptomatic spleen enlargement |

| Ascites or pleural effusion |

| Cytopenias (neutrophil counts <1 G/L or platelet counts <100 G/L) |

| Circulating lymphoma cells (>5.0 G/L) |

| The presence of any 1 of these criteria defines a patient with a high tumor burden |

| A lymphoma tumor ≥7 cm in diameter* |

| Three nodes in 3 distinct areas, with each node ≥3 cm in diameter |

| Presence of systemic symptoms |

| Symptomatic spleen enlargement |

| Ascites or pleural effusion |

| Cytopenias (neutrophil counts <1 G/L or platelet counts <100 G/L) |

| Circulating lymphoma cells (>5.0 G/L) |

Except spleen.

Mutation4 or gene expression profiling5 data have been proposed as new prognostic parameters for patients undergoing first-line therapy, but they lack robust reproducibility with different therapeutic strategies and cannot inform us about treatment selection. Similarly, although some biological and clinical differences exist between patients with histological grade 1 to 2 vs grade 3A follicular lymphoma,6 management is broadly similar between the two groups.

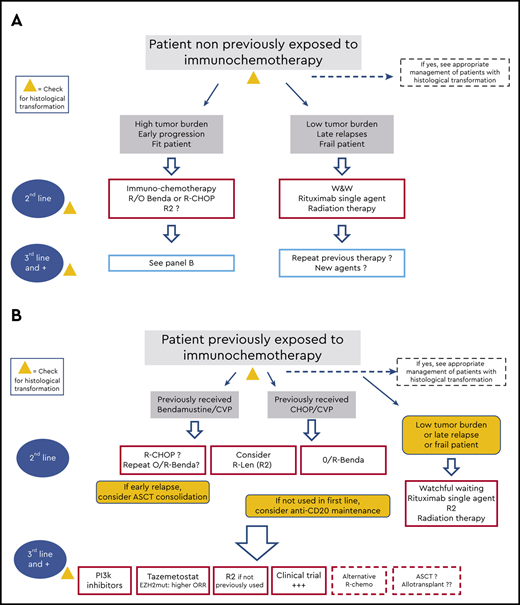

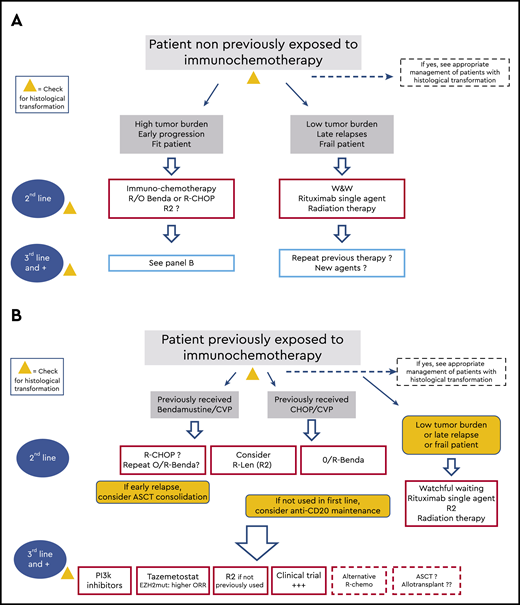

Although the need to address treatment sequencing implies that the first line of therapy has failed, we will briefly review the options initially adopted, because they also determine the choice of the next sequences (Figure 1). The three clinical cases below will help us walk through these different sequences of therapy.

Patient 1: On the basis of a biopsy of a 3-cm cervical lymph node, an asymptomatic 58-year-old woman received a diagnosis of follicular lymphoma grade 1 to 2, Ann Arbor stage I. She received involved-site radiation (24 Gy) in 2000 and had disease relapse in 2010, with small (1- to 1.5-cm) cervical and axillary nodes and a low tumor burden according to Groupe d’Etude des Lymphomes Folliculaires criteria. She remained asymptomatic.

Patient 2: A 45-year-old man with follicular lymphoma grade 2, Ann Arbor stage III, and a high tumor burden was treated in a clinical trial with rituximab–cyclophosphamide, hydroxydaunorubicin, vincristine sulfate, and prednisone (R-CHOP) followed by 2 years of rituximab maintenance in 2005. He presented with a disseminated disease recurrence 16 months after initiating the maintenance. The new biopsy showed follicular lymphoma grade 3A; the bone marrow biopsy showed no lymphoma infiltration.

Patient 3: A 67-year-old woman was treated in 2014 for follicular lymphoma grade 1, Ann Arbor stage IV, with 6 cycles of bendamustine and rituximab. She presented with a disseminated disease recurrence 5 years later. A new biopsy confirmed follicular lymphoma with an unchanged grade.

Schematic indications of the potential sequence of treatment during the clinical course of patients with follicular lymphoma. (A) Treatment options for patients who did not receive immunochemotherapy in the first line. (B) Options for patients for whom immunochemotherapy failed. W&W, watchful waiting.

Schematic indications of the potential sequence of treatment during the clinical course of patients with follicular lymphoma. (A) Treatment options for patients who did not receive immunochemotherapy in the first line. (B) Options for patients for whom immunochemotherapy failed. W&W, watchful waiting.

Current options for the first therapeutic sequence

At diagnosis, we can face three different situations:

1. Patients with strictly localized disease

2. Patients with disseminated disease but low tumor burden and no immediate treatment indication

3. Patients with a clear indication for systemic treatment or high tumor burden

Patients with localized disease

For patients with stage I or contiguous stage II disease without tumor bulk or biological pejorative features who were adequately staged with positron emission tomography–computed tomography (PET-CT) scans and bone marrow biopsy, involved-site radiation therapy is the preferred option according to the National Comprehensive Cancer Network7 and European Society for Medical Oncology8 guidelines, with the expectation that it will be curative. Data from the LymphoCare observational study suggested that the interval without lymphoma progression was similar between patients who underwent radiation therapy and patients who underwent watchful waiting.9 The same study indicated that combined therapy (radiation therapy and systemic therapy) might be the best option to achieve a longer progression-free interval. In line with this observation, a recent randomized study indicated that systemic treatment after radiation therapy for patients with localized disease significantly increased 10-year progression-free survival (PFS) from 41% without adjuvant systemic therapy to 59% with adjuvant cyclophosphamide, vincristine, and prednisone (CVP) or rituximab-CVP (R-CVP).10 Although this study has several limitations (heterogeneity of histological profiles and therapies, length of accrual), it provides further evidence to support systemic treatment in addition to radiation therapy.11,12 Which regimen to administer (rituximab alone or in combination with chemotherapy), when to sequence it (before or after radiation therapy), and how to administer it (schedule and length) remain unanswered. What is likely, however, is that more patients with localized disease will be treated with combined modality therapy in the near future.

Patients with a low tumor burden

For patients with no formal indication for treatment (low tumor burden, asymptomatic, and no rapid clinical progression), watchful waiting remains the standard course. However, rituximab single-agent therapy has become a popular option for these patients on the basis of multiple phase 2 studies and 1 randomized study showing a significant increase in PFS after 4 single infusions of rituximab.13 There is no evidence that early administration of rituximab impairs the efficacy of second-line therapy. However, it is questionable to use this strategy with the goal of delaying the use of immunochemotherapy (cytotoxic agent plus an anti-CD20 antibody), because the application of this combination has clearly demonstrated a significant reduction in the risk of death for patients with follicular lymphoma.

Patients with high tumor burden

Combinations of either bendamustine, CHOP, or CVP with rituximab (R-benda, R-CHOP, and R-CVP, respectively) or obinutuzumab (O-benda, O-CHOP, and O-CVP) make up the current standard treatment options for patients with a high tumor burden. Bendamustine has been widely adopted in different regions of the globe, given its lower toxicity profile, in terms of neutropenia, and the lack of drug-induced alopecia. The use of bendamustine also spares administration of anthracyclines, which can be useful in later lines, specifically if histological transformation occurs. However, data from the GALLIUM study indicated that the use of R- and O-benda followed by 2 years of antibody maintenance was associated with a significant risk of adverse events, including fatal ones.14 In the same study, obinutuzumab with the different chemotherapy backbones was shown to increase PFS, compared with rituximab-based combinations (5-year PFS, 70.5% vs 63.2%15 ), although its use was associated with more side effects (all manageable). Altogether, given the lack of an overall survival benefit associated with one of these options over the others, the choice of both the chemotherapy backbone and the anti-CD20 antibody for this first immunochemotherapy sequence, followed or not by anti-CD20 maintenance, should be made according to physician and patient preferences. However, this choice will have significant consequences for potential next sequences, as outlined below.

Is there an optimal therapeutic sequence in the second line?

For chemotherapy-naive patients

For patients treated with radiation therapy or rituximab single-agent therapy who need a new line of treatment, the next sequence consists of an immunochemotherapy regimen in most cases. At this stage, all of the regimens previously discussed as first lines are acceptable. The recently approved lenalidomide–rituximab (R2) combination is also an acceptable option.16 For a few patients, either frail, elderly, or with a low tumor burden and very long response to rituximab single-agent therapy (>5 years), rituximab single-agent therapy can be repeated, or radiation therapy can be used with different modalities, including the 2- × 2-Gy symptomatic but efficient schedule.

After first-line immunochemotherapy

For patients who have received immunochemotherapy, it appears logical to propose an alternative cytotoxic regimen, usually one combined with an anti-CD20 antibody. In cases where CHOP or CVP was used as the chemotherapy backbone in the first line, bendamustine is a favorite choice. O-benda followed by obinutuzumab maintenance was approved for patients with disease refractory to rituximab, with a significant overall survival benefit (hazard ratio of 0.67 favoring this regimen over bendamustine alone).17 Despite the limitations of this study (lack of rituximab in the control arm and anti-CD20 maintenance administered only in the experimental arm), it established this regimen as a favorite option for patients with rituximab-refractory disease who have previously received R-CVP or R-CHOP, and its use has been expanded beyond patients with refractory disease.

We lack solid data on the efficacy of an alternative chemotherapy after R- or O-benda as first-line therapy, including R-CHOP, which is frequently used.3 Bendamustine can be used again but not without significant risks of cumulative hematological toxicities, and it should not be recommended if the interval between treatments is short (<1 or 2 years; an interval of 2 years was recommended in the GADOLIN study18 ). Of note, many regimens that combine cytotoxic agents and are used to treat aggressive B-cell malignancies, such as rituximab, dexamethasone, high‐dose cytarabine, and cisplatin/oxaliplatin,19 can also be effective in the setting of disease relapse.3 There are no data regarding the optimal anti-CD20 antibody for patients who have received obinutuzumab as first-line therapy.

R2 was recently approved for patients whose disease was not refractory to rituximab, after demonstration of its superiority to rituximab single-agent therapy, with a significant increase in PFS (39 months vs 14 months) and excellent overall survival probability (93% at 2 years) (Table 2).15 Side effects were essentially represented by infections, neutropenia (often of grade 3 to 4), and cutaneous rashes. Although long-term data are not yet available, this regimen, or its variant where obinutuzumab is replacing rituximab in combination with lenalidomide (eg, as reported in the GALEN study20 ) have an acceptable tolerability and a fixed treatment duration, and they are attractive options in this setting.

Key results of the AUGMENT study for patients with follicular lymphoma15

| Treatment arm . | Number of patients* . | ORR . | CRR . | PFS, median (mo) . | DOR, median (mo) . | 2-y OS . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rituximab single agent | 148 | 55% | 29% | 14 | 22 | 87% |

| Lenalidomide–rituximab (R2) | 147 | 80% | 51% | 39 | 37 | 93% |

| P | <.0001 | .004 | <.0001 | <.0001 | .02 |

| Treatment arm . | Number of patients* . | ORR . | CRR . | PFS, median (mo) . | DOR, median (mo) . | 2-y OS . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rituximab single agent | 148 | 55% | 29% | 14 | 22 | 87% |

| Lenalidomide–rituximab (R2) | 147 | 80% | 51% | 39 | 37 | 93% |

| P | <.0001 | .004 | <.0001 | <.0001 | .02 |

CRR, complete response rate; DOR, duration of response; ORR, overall response rate; OS, overall survival.

All detailed results are provided for patients with follicular lymphoma.

Should responding patients receive any form of consolidation in the second line?

In the mid-2000s, the EORTC study indicated significant outcome improvement when rituximab maintenance was administered after CHOP or R-CHOP for patients who were previously rituximab naive.21 Results of other studies supported the benefit of rituximab maintenance for patients with relapsed or refractory disease, and a meta-analysis showed a significant benefit in overall survival.22 However, in the setting of anti-CD20 maintenance administered during first-line therapy, data regarding the risk/benefit ratio of another maintenance consolidation are lacking.

Multiple studies have shown that autologous stem cell transplant (ASCT) can achieve durable responses for patients with relapsed or refractory follicular lymphoma, and this strategy has been widely used by some institutions.23-25 A comparison based on registry and cohort data suggested that ASCT (as a consolidation after salvage therapy) improved survival for patients with early treatment failure.26 However, data from the PRIMA study indicated that there was no benefit in overall survival with ASCT for patients without evidence of histological transformation.13

Early progression or early histological transformation?

Several years ago, attention was brought to patients treated with first-line immunochemotherapy (essentially consisting of R-CHOP) who had experienced disease progression within 24 months after diagnosis: Their risk of death was significantly higher than that of patients who did not have disease progression, with only 50% alive at 5 years.27 Other observations extended these findings to patients for whom observation was adopted at presentation and who had disease progression within 12 months, and to patients treated with single-agent rituximab or radiation therapy.14,28 However, when early failure after immunochemotherapy was considered, a variable but substantial proportion of these patients presented with histological transformation of their lymphoma, from 35% to >75%, with the higher rates observed after use of a bendamustine-containing regimen.29,30 Details about the treatment of patients with transformed disease are provided in a companion paper of this series by S. Smith,31 and outcomes after transformation remain dismal. However, few data are available regarding outcomes and prognoses of patients with early progression of disease without histological transformation. This lack of data supports the need to document early progression with a new biopsy, preferentially performed in the lesion with the highest standardized uptake value on PET-CT scan. At present, there is a trend to adopt a different therapeutic strategy (including consideration for ASCT) for patients with early failure after first-line therapy (having experienced a progression at 12 or 4 months), given the poorer outcomes among these patients,32 but robust data are lacking in this area. Results of ongoing studies using targeted therapies for patients with relapsed or refractory disease suggest that several approaches are effective in this population.

For patient 1, rituximab single-agent therapy (rather than repeating radiation therapy, because 2 distinct sites of lymphoma involvement were present) would be a good option, but it is also acceptable to pursue surveillance for a couple of months or years before initiating therapy for patients who are adherent and accept this strategy.33

For patient 2, despite a biopsy in the largest and more metabolic (standardized uptake value of 13) abdominal lesion, histological transformation was not demonstrated (change of histological grading does not constitute a specific indication). Two options were discussed with the patient: a combination of O-benda for 6 cycles followed by 2 years of obinutuzumab or a shorter duration of second-line therapy (rituximab, dexamethasone, cytarabine, and oxaliplatin ×3) consolidated (if responsive to salvage therapy) with ASCT. The use of maintenance after ASCT with rituximab every 3 months was not adopted, because the patient had already received maintenance in the first line of therapy and because of the lack of robust data supporting a second sequence of maintenance.

For patient 3, R2, according to the AUGMENT study, was chosen. Other options, such as R-CVP or R-CHOP, were considered to be more toxic but could also have been proposed.

Managing chronicity

For patients receiving a third line of therapy or beyond, several new options are available, such as phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) inhibitors and, recently, the enhancer of zeste homolog 2 (EZH2) inhibitor tazemetostat.

The PI3K inhibitors

Three inhibitors of the PI3K pathway have been approved for use in the United States (only 1 in Europe) (Table 3). The first, idelalisib, is an oral agent specific to the δ isoform of this enzyme. It has proven efficacy for patients with double-refractory disease to rituximab and alkylating agents. However, the pattern of initial (transaminitis, neutropenia) and mid- or long-term (diarrhea, colitis, pneumonitis, opportunistic infections) side effects necessitates attentive clinical management.34 Some patients still enjoy a prolonged benefit, and dosage adaptations can sometimes increase tolerability.35 Duvelisib is also an oral agent that targets the δ and γ PI3K isoforms. With the usual limitations of cross-study comparisons, the response rate observed in the pivotal trial was slightly lower than that of idelalisib, and the tolerability was similar (liver enzyme elevations were less common).36 Copanlisib is specific for the α and δ isoforms of PI3K, but it is administered intravenously for 3 weeks out of 4, with some precautions regarding the risk of hyperglycemia and hypertension; altogether, it has a tolerability profile a little different from that of the other options.37 Overall, these agents are useful, but few patients have a complete response, and the median response duration rarely exceeds 1 year (Table 3).

Key results of the different currently available PI3K inhibitors

| Drug . | Disease characteristics . | Number of patients (total/follicular) . | ORR . | CRR . | PFS, median (mo) . | DOR, median (mo) . | 2-y OS . | Most common grade 3-4 adverse events (present in ≥5% of patients)* . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Idelalisib27,28 | Double refractory to rituximab and alkylating agents | 72/125 | 66%† | 14%† | 11 (11†) | 12 (11†) | 70%† | Neutropenia (27%) |

| ALT elevation (13%) | ||||||||

| Diarrhea (13%) | ||||||||

| Pneumonia (7%) | ||||||||

| Thrombocytopenia (6%) | ||||||||

| Duvelisib14 | Double refractory to rituximab and alkylating agents | 129/83 | 42%† | 1%† | 10 | 10 | ∼60%‡ | Neutropenia (25%) |

| Diarrhea (15%) | ||||||||

| Anemia (15%) | ||||||||

| Thrombocytopenia (12%) | ||||||||

| Febrile neutropenia (9%) | ||||||||

| Lipase increased (7%) | ||||||||

| ALT elevation (5%) | ||||||||

| Pneumonia (5%) | ||||||||

| Colitis (5%) | ||||||||

| Copanlisib29 | Relapsed or refractory after 2 lines of therapy | 142/104 | 59%† | 20%† | 13 | 14 | 69% augment | Hyperglycemia (40%) |

| Hypertension (24%) | ||||||||

| Neutropenia (24%) | ||||||||

| Pneumonia (11%) | ||||||||

| Diarrhea (9%) | ||||||||

| Anemia (5%) | ||||||||

| Thrombocytopenia (5%) |

| Drug . | Disease characteristics . | Number of patients (total/follicular) . | ORR . | CRR . | PFS, median (mo) . | DOR, median (mo) . | 2-y OS . | Most common grade 3-4 adverse events (present in ≥5% of patients)* . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Idelalisib27,28 | Double refractory to rituximab and alkylating agents | 72/125 | 66%† | 14%† | 11 (11†) | 12 (11†) | 70%† | Neutropenia (27%) |

| ALT elevation (13%) | ||||||||

| Diarrhea (13%) | ||||||||

| Pneumonia (7%) | ||||||||

| Thrombocytopenia (6%) | ||||||||

| Duvelisib14 | Double refractory to rituximab and alkylating agents | 129/83 | 42%† | 1%† | 10 | 10 | ∼60%‡ | Neutropenia (25%) |

| Diarrhea (15%) | ||||||||

| Anemia (15%) | ||||||||

| Thrombocytopenia (12%) | ||||||||

| Febrile neutropenia (9%) | ||||||||

| Lipase increased (7%) | ||||||||

| ALT elevation (5%) | ||||||||

| Pneumonia (5%) | ||||||||

| Colitis (5%) | ||||||||

| Copanlisib29 | Relapsed or refractory after 2 lines of therapy | 142/104 | 59%† | 20%† | 13 | 14 | 69% augment | Hyperglycemia (40%) |

| Hypertension (24%) | ||||||||

| Neutropenia (24%) | ||||||||

| Pneumonia (11%) | ||||||||

| Diarrhea (9%) | ||||||||

| Anemia (5%) | ||||||||

| Thrombocytopenia (5%) |

ALT, alanine transaminase; CRR, complete response rate; DOR, duration of response; ORR, overall response rate; OS, overall survival.

*Collected on all patients analyzed in the study.

†Patients with follicular lymphoma only.

‡Estimated from OS curve.

Epigenetic targeting

The transcription factor EZH2 plays a key role in germinal center formation, and the gene presents an activating mutation in ∼20% of patients with follicular lymphoma. Tazemetostat is the first-in-class inhibitor of this pathway, and this oral drug was found to be more active in EZH2-mutated cases than in unmutated cases, although the response duration was comparable between cohorts (Table 4).38 The side effects are quite limited, essentially of grade 1 to 2, and include low-grade nonspecific digestive symptoms, alopecia, or fatigue. On the basis of these data, the drug was recently approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) “for adult patients with relapsed or refractory (R/R) follicular lymphoma (FL) whose tumors are positive for an EZH2 mutation as detected by an FDA-approved test and who have received at least 2 prior systemic therapies, and for adult patients with R/R FL who have no satisfactory alternative treatment options.”

Key results of the pivotal tazemetostat study30

| Patient cohort . | Number of patients . | ORR (by IRC) . | CRR . | PFS, median (mo) . | DOR, median (mo) . | Treatment-related adverse events (any grade) in ≥10% of patients . | Treatment-related adverse events (grade 3-4) in ≥2% of patients . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EZH2 mutated | 45 | 69% | 13% | 14 | 11 | Nausea (19%) | Anemia (2%) |

| EZH2 wild-type | 54 | 35% | 4% | 11 | 13 |

|

|

| Patient cohort . | Number of patients . | ORR (by IRC) . | CRR . | PFS, median (mo) . | DOR, median (mo) . | Treatment-related adverse events (any grade) in ≥10% of patients . | Treatment-related adverse events (grade 3-4) in ≥2% of patients . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EZH2 mutated | 45 | 69% | 13% | 14 | 11 | Nausea (19%) | Anemia (2%) |

| EZH2 wild-type | 54 | 35% | 4% | 11 | 13 |

|

|

CRR, complete response rate; DOR, duration of response; IRC, independent review committee; ORR, overall response rate.

Can we also consider reusing rituximab?

Single-agent rituximab in cases of late relapse, the use of a different immunochemotherapy regimen when the disease volume is substantial, and the R2 combination if not previously prescribed are all acceptable options. Of note, the concept of rituximab resistance was developed as a pathway for drug development and regulatory approval but is not well documented biologically, and patients who did not have a response to rituximab once may still have a response months or years later.39,40

Are autologous and allogeneic transplants viable options in 2020?

Although it is probably more efficient at the time of first relapse, ASCT can still be considered in later lines41 ; for patients who are fit and for whom a donor is available, allogeneic transplant (with a reduced-intensity conditioning regimen) can also be proposed and may offer a sustained duration of response in a substantial proportion of patients.42

Future developments

Of the different agents in development, it is worth mentioning that bispecific antibodies have achieved promising results for patients with follicular lymphoma.43,44 Recently, preliminary results with chimeric antigen receptor T cells (axicabtagene ciloleucel) have been encouraging (Table 5). Therefore, offering patients the opportunity to participate in a clinical trial that is evaluating new agents, alone or in combination, should always be considered, given the multiplicity of active drugs evaluated in follicular lymphoma.45

Early results with selected new therapies in development for follicular lymphoma

| Studies . | Number of patients . | ORR . | CRR . | Main adverse events . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

| Cytokine release syndrome and ICANS (essentially grade 1-2), cytopenias (20%-25% grade ≥3) | |

| 80 | 95% | 81% | Cytokine release syndrome (7% grade ≥3), ICANS (15% grade ≥3), cytopenias |

| Studies . | Number of patients . | ORR . | CRR . | Main adverse events . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

| Cytokine release syndrome and ICANS (essentially grade 1-2), cytopenias (20%-25% grade ≥3) | |

| 80 | 95% | 81% | Cytokine release syndrome (7% grade ≥3), ICANS (15% grade ≥3), cytopenias |

CRR, complete response rate; ICANS, immune effector cell–associated neurotoxicity syndrome; ORR, overall response rate.

Conclusions

Assuming that histological transformation has been ruled out, the prognosis of patients with relapsed or refractory follicular lymphoma remains uncertain but not necessarily dismal. Multiple treatment options are available, and it is often possible to alternate regimens or drugs that might differ in terms of side effects and duration in the hope of achieving treatment-free intervals. In a reasonable proportion of patients, this approach may control the recurrent disease for 1 or 2 decades and allow the patient to access new forms of therapy that could be more efficient.

Epilogue

Patient 1: Although the usual rituximab regimen consists of 4 weekly rituximab infusions, in this situation I usually advise completing therapy with 4 additional infusions administered every 2 months, which nearly doubles the time to progression.46 The patient experienced 3 years without symptoms and without treatment. In 2014, a new progression occurred, and the patient received her first chemotherapy, 6 cycles of R-benda, with a complete response on PET-CT scan at the end of treatment. A new progression was observed in 2017, and the patient participated in a study evaluating obinutuzumab and lenalidomide with obinutuzumab maintenance. She had a complete response at the end of this treatment in 2019.

Patient 2: The patient opted for ASCT. He experienced a complete response lasting 6 years. Progression with a limited tumor burden occurred at that time, and the patient received rituximab single-agent therapy but had progression within 6 months of the end of therapy. He received idelalisib for 8 months, stopping because of poor tolerability. He remained with limited and asymptomatic disease for ∼1 year and then started R-benda, which was interrupted after 4 cycles for persistent neutropenia, with a good partial response. He was recently treated with chimeric antigen receptor T cells in a clinical trial and had a new complete response.

Patient 3: The patient had a response to R2. She had limited disease progression 2 years later and is currently undergoing observation. She is a good candidate for other new agents (eg, PI3K or EZH2 inhibitors, bispecific antibodies) in the near future.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure

G.S. has received honoraria for consultancy, participation in advisory boards, and educational events from Abbvie, Allogene, Autolus, Beigene, Celgene, Genmab, Gilead, Janssen, Kite, Morphosys, Novartis, Roche, Servier, and Velosbio.

Off-label drug use

Obinutuzumab

Correspondence

Gilles Salles, 540 E 74th St, New York, NY 10065; e-mail: sallesg@mskcc.org.