Abstract

Anticoagulation is central to the management of antiphospholipid syndrome (APS), an acquired thrombo-inflammatory disorder characterized by thrombosis (venous, arterial, or microvascular) or pregnancy morbidity, in association with persistent antiphospholipid antibodies (aPL; ie, 1 or more of lupus anticoagulant [LA], anticardiolipin, anti-beta-2- glycoprotein I, IgG, or IgM antibodies). The mainstay of anticoagulation in patients with thrombotic APS is warfarin or an alternative vitamin K antagonist (VKA) and, in certain situations, low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) or unfractionated heparin (UFH). Accurate assessment of anticoagulation intensity underpins optimal anticoagulant dosing for thrombus treatment or primary/secondary prevention. In patients with APS on warfarin, the international normalized ratio (INR) may not be representative of anticoagulation intensity due to an interaction between LA and the thromboplastin reagent used in the INR determination. In this review, we summarize the use of warfarin/VKA in patients with APS, along with venous and point-of-care INR monitoring. We also discuss the role and monitoring of LMWH/UFH, including in the anticoagulant refractory setting and during pregnancy.

Learning Objectives

Describe the use of warfarin and low-molecular-weight heparin/unfractionated heparin in patients with antiphospholipid syndrome

Discuss strategies for monitoring these anticoagulants in patients with antiphospholipid syndrome

CLINICAL CASE 1

A 45-year-old man presented with an unprovoked left common femoral deep vein thrombosis. He was commenced on rivaroxaban. Investigations showed triple-positive antiphospholipid antibodies (aPL) (ie, the presence of lupus anticoagulant [LA], anticardiolipin [aCL], and anti-beta-2-glycoprotein I [aβ2GPI] antibodies), with high positive1 aCL (>100 GPLU (IgG antiphospholipid units)/mL) and aβ2GPI IgG (>100 U/mL), by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Following a discussion about anticoagulant choice in individuals with venous thromboembolism (VTE) and triple-positive aPL, rivaroxaban was transitioned to long-term warfarin with a target international normalized ratio (INR) of 2.5, range 2.0-3.0 (standard intensity).

CLINICAL CASE 2

A 22-year-old woman presented with transient right lower limb weakness and was diagnosed with a transient ischemic attack (TIA). Three years later, while on clopidogrel, she developed a right middle cerebral artery acute ischemic stroke (AIS). Testing for aPL demonstrated persistent moderate positive1 aCL (43 GPLU/mL) and aβ2GPI IgG (61 U/mL) by ELISA. No other stroke/TIA etiology was identified. Clopidogrel was transitioned to warfarin, with a target INR of 3.5, range 3.0–4.0 (high intensity), our usual antithrombotic treatment in individuals with aPL-associated AIS.

Introduction

Anticoagulation is central to the management of thrombotic antiphospholipid syndrome (APS), an acquired thrombo-inflammatory disorder characterized by thrombosis (venous, arterial, or microvascular) or pregnancy morbidity in association with persistent aPL (ie, 1 or more of LA, aCL, aβ2GPI, IgG, or IgM).1,2 In patients with systemic lupus erythematosus, aPL are common (reported prevalence: 26%, 47% and 33% for LA, aCL and aβ2GPI, respectively).3

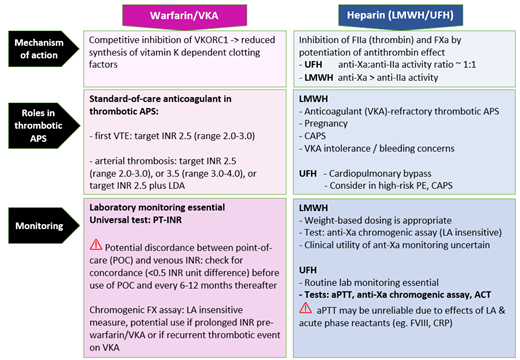

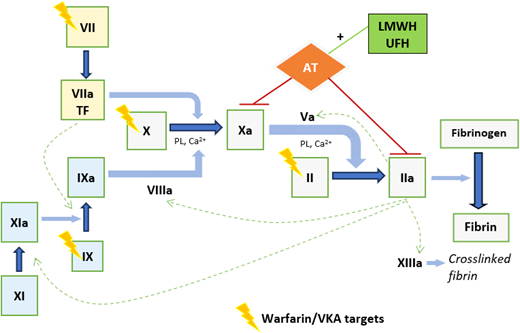

The mainstay of anticoagulation in patients with APS is warfarin or an alternative vitamin K antagonist (VKA) and, in some situations, low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) or unfractionated heparin (UFH).4,5 Respective anticoagulant mechanisms are outlined in Figure 1. Accurate assessment of anticoagulation intensity underpins optimal anticoagulant dosing for thrombus treatment or primary/secondary prevention; informs assessment of whether recurrent thrombosis is related to breakthrough thrombosis while on therapeutic anticoagulation, subtherapeutic anticoagulation, nonadherence, or spurious results; and guides the management of bleeding complications. In patients with APS on warfarin, the INR may not be representative of true anticoagulation intensity due to an interaction between LA and the thromboplastin reagent used in the INR determination. Other pertinent issues in APS patients include use and monitoring of LMWH/UFH, including in the context of anticoagulant refractory thrombosis and pregnancy.

Anticoagulant mechanisms of warfarin/VKA and LMWH/UFH. Figure 1 provides a simplified representation of coagulation cascade showing targets of warfarin/VKA and LMWH/UFH. Warfarin/alternative VKA reduces synthesis of functional vitamin K–dependent coagulation factors; the mechanism is by competitive inhibition of vitamin K epoxide reductase enzyme, depleting functional vitamin K required for gamma-carboxylation of coagulation factors II, VII, IX, and X. LMWH/UFH potentiate the inhibition of factor Xa and thrombin (IIa), by antithrombin (AT), and also factors IXa and XIa. This prevents fibrin formation and inhibits thrombin- induced activation of platelets and factors V, VIII, XI, and XIII. Heparin binds to AT via a high-affinity pentasaccharide binding site. Maximal anti-IIa activity requires binding to AT and IIa simultaneously, with heparin acting as a bridge, and depends on a minimum heparin chain length (>18 saccharide units), unlike anti-Xa activity, which requires binding to AT only. LMWH, with its shorter average chain length, has lower anti-IIa activity than UFH, and its anticoagulant effect is predominantly from anti-Xa activity. Ca2+, calcium; PL, phospholipid; TF, tissue factor.

Anticoagulant mechanisms of warfarin/VKA and LMWH/UFH. Figure 1 provides a simplified representation of coagulation cascade showing targets of warfarin/VKA and LMWH/UFH. Warfarin/alternative VKA reduces synthesis of functional vitamin K–dependent coagulation factors; the mechanism is by competitive inhibition of vitamin K epoxide reductase enzyme, depleting functional vitamin K required for gamma-carboxylation of coagulation factors II, VII, IX, and X. LMWH/UFH potentiate the inhibition of factor Xa and thrombin (IIa), by antithrombin (AT), and also factors IXa and XIa. This prevents fibrin formation and inhibits thrombin- induced activation of platelets and factors V, VIII, XI, and XIII. Heparin binds to AT via a high-affinity pentasaccharide binding site. Maximal anti-IIa activity requires binding to AT and IIa simultaneously, with heparin acting as a bridge, and depends on a minimum heparin chain length (>18 saccharide units), unlike anti-Xa activity, which requires binding to AT only. LMWH, with its shorter average chain length, has lower anti-IIa activity than UFH, and its anticoagulant effect is predominantly from anti-Xa activity. Ca2+, calcium; PL, phospholipid; TF, tissue factor.

This review addresses key considerations in the choice of anticoagulant and anticoagulant dosing and monitoring, as highlighted by the 2 clinical cases.

The role of warfarin versus direct oral anticoagulants in thrombotic APS

Warfarin, or an alternative VKA, is the standard anticoagulant treatment for thrombotic APS.4 The presence of aPL strengthens the decision to offer life-long anticoagulation following a first unprovoked VTE,6 with aPL and raised D-dimer independent risk factors for recurrence.7 A target INR range of 2.0-3.0 is recommended following a first VTE.4 In patients with aPL-associated AIS or other arterial thrombosis, substantive evidence to guide antithrombotic treatment is lacking. The European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology (EULAR) makes the following recommendations4 based on a systematic review8: VKA at target INR range 2.0-3.0 or 3.0-4.0, taking into consideration the individual’s risk of bleeding and recurrent thrombosis; or consideration of VKA at target INR range 2.0-3.0, plus low dose aspirin (LDA). In patients with recurrent thrombosis on warfarin, options include addition of LDA, an increased target INR range of 3.0-4.0 if the event occurred while on standard-intensity warfarin, or transition to LMWH.4,9 Warfarin should be used with caution in APS patients with thrombocytopenia, present in 27% of 1000 APS patients in the Euro-Phospholipid project,10 in view of its long half-life.

Direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) are the standard of care for anticoagulation following a first VTE in the general population. However, special considerations apply to their use in APS patients. A meta-analysis of DOAC randomized controlled trials (RCTs) in patients with APS (N = 472) noted a significantly higher risk of subsequent acute ischaemic stroke during treatment with DOACs compared to warfarin/VKA (absolute incidence 8.6% vs 0%; OR, 10.74 [95% CI, 2.29-50.38]), although the risk of subsequent VTE was not increased. As a result, 2 of the trials were terminated early.11 The International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis (ISTH) guidance12 recommends

against the use of DOACs in APS patients with arterial thrombosis or triple-aPL positivity; and

consideration of continuation of the DOAC in non-high-risk APS patients with single- or double-positive aPL who have been on a DOAC as standard of care treatment following a first episode of VTE.

All DOAC RCTs in APS used standard treatment dose DOAC, or prophylactic dose.13 RISAPS (Rivaroxaban in Stroke Patients with APS) is a proof-of-principle phase 2b RCT assessing for noninferiority of high-dose rivaroxaban compared with high-intensity warfarin for APS patients with AIS, TIA, or other brain ischemic injury.14

Anticoagulant monitoring of warfarin or alternative VKA in APS patients

The prothrombin time–international normalized ratio (PT-INR) is the test universally used to monitor warfarin anticoagulation. The INR is derived from the PT according to this formula: INR = (patient's PT/MNPT)ISI, where the MNPT is the mean normal PT and ISI is the international sensitivity index. The ISI standardizes the differences between PTs by comparison with an international reference preparation thromboplastin reagent. Accurate INR determination depends on defining the MNPT and ISI for the reagent/instrument combination, and guidance is available for appropriate ISI verification/validation to help reduce interlaboratory variation.15 LA-induced PT prolongation may occur, as LA can affect phospholipid dependent coagulation tests; however, the high phospholipid concentration in PT-INR reagents neutralizes LA activity, and makes this phenomenon unusual.16 A multicenter study demonstrated that differences in venous PT-INR results, when measured with most commercial thromboplastins, are not enough to cause concern if thromboplastins that are insensitive to LA and instrument-specific ISI values are used.17 Recombinant thromboplastins produce higher INRs, which could potentially influence clinical management; this is related to their composition of relipidated phospholipid.16 The PT can also be prolonged by LA effect associated with the rare LA-hypoprothrombinemia syndrome, characterized by acquired factor II deficiency.18

ISTH recommendations16 state that PT-INR measured with the vast majority of commercial thromboplastins can be safely used to monitor LA-positive patients on warfarin/VKA, keeping in mind that there may be occasional patients for whom the INR is affected by LA. New thromboplastins, especially if recombinant, should be checked for sensitivity to LA before they are used to monitor warfarin. In APS patients requiring anticoagulation, baseline PT should be performed, if possible, to identify individual patients who may benefit from INR monitoring with an LA-insensitive thromboplastin.

Several point-of-care (POC) devices have been shown to give reliable and accurate INR values when compared to traditional laboratory INRs.19 Patient self-management (PSM) has been shown to reduce the risk of mortality and recurrent pulmonary embolism and DVT, and patient self-testing (PST) possibly reduces the risk of VTE and major bleeding.20 Accordingly, for patients on VKA, the American Society of Hematology (ASH) recommends PSM over any other anticoagulation monitoring approach and suggests use of PST.20 POC INR testing, however, shows variable results in patients with APS. Taylor et al21 found that the mean INR difference between the CoaguChek XS and laboratory INR was 0.68 (standard deviation 0.67), with a significantly higher difference in patients with APS than in control patients at target INR 2.5. Isert et al22 did not find a higher disagreement between CoaguChek vs laboratory INRs using 2 thromboplastins in patients with APS; however, agreement between the INR and the chromogenic factor X (CFX)-derived INR equivalent was less frequently observed in these patients versus controls (55.6% vs 67.8%, P = 0.05; threshold for statistical significance P < 0.05). A pragmatic approach in patients with APS is to use POC INR testing in those who exhibit concordance of POC versus venous (laboratory) INR (difference <0.5 INR units) (Table 1).23 These issues should be discussed with patients prior to embarking on self-testing.

Monitoring of warfarin/vitamin K antagonists in patients with antiphospholipid syndrome

| Monitoring test . | Type of assay . | Target range . | Points to note . |

|---|---|---|---|

| PT-INR (venous) | Clotting assay INR = PT/MNPT | 2.0-3.0 3.0-4.0 | • Venous (laboratory) INR standard test to monitor VKA anticoagulation intensity in APS patients • Ensure new thromboplastins have low sensitivity to LA before using to monitor VKA • Define MNPT and ISI for reagent/instrument combination • Check baseline PT before anticoagulation, if possible • If baseline PT prolonged, check for acquired factor II deficiency (LA-hypoprothrombinemia syndrome) |

| PT-INR (point-of-care) | Clotting assay INR = PT/MNPT | 2.0-3.0 3.0-4.0 | • Reliable, accurate INRs versus venous INRs in general population • Interpret with caution in APS patients - may be discordant versus venous INRs Pragmatic approach for APS patients: In patients using POC INRs (including self-testing/self-monitoring), via an anticoagulation clinic, ensure: • Check for concordance versus venous INRs (ie, <0.5 INR unit difference) before use for monitoring: initially on three occasions when venous INR in therapeutic range, thereafter, suggest check concordance once every 6-12 months • Regular internal quality control: run at minimum when testing a new batch of test strips or if unexpectedly high or low INR • Regular external quality assessment |

| Chromogenic factor X | Chromogenic assay | ~40%–20% = INR 2.0-3.0 | • LA-independent measure of anticoagulant intensity • Therapeutic ranges not established • Poor utility at INRs >3.0 (equivalent to chromogenic factor X < 12 IU/dL; ie, inverse relationship) • Not widely available or practicable for routine use • Could assist (1) in INR monitoring when prolonged INR before warfarin/VKA; or (2) if recurrent thrombotic event while on apparently therapeutic VKA anticoagulation |

| Thrombin generation | Fluorogenic substrate, continuous measurement of TG | Therapeutic range not established | • ETP and peak TG showed significant inverse correlations with INR in non-APS and APS patients24 • A subgroup of APS patients with increased peak TG, despite therapeutic INR and CFX, suggests that TG might identify an ongoing prothrombotic state24 • The use of TG remains limited to specialized laboratories due to lack of standardization and established therapeutic ranges |

| Monitoring test . | Type of assay . | Target range . | Points to note . |

|---|---|---|---|

| PT-INR (venous) | Clotting assay INR = PT/MNPT | 2.0-3.0 3.0-4.0 | • Venous (laboratory) INR standard test to monitor VKA anticoagulation intensity in APS patients • Ensure new thromboplastins have low sensitivity to LA before using to monitor VKA • Define MNPT and ISI for reagent/instrument combination • Check baseline PT before anticoagulation, if possible • If baseline PT prolonged, check for acquired factor II deficiency (LA-hypoprothrombinemia syndrome) |

| PT-INR (point-of-care) | Clotting assay INR = PT/MNPT | 2.0-3.0 3.0-4.0 | • Reliable, accurate INRs versus venous INRs in general population • Interpret with caution in APS patients - may be discordant versus venous INRs Pragmatic approach for APS patients: In patients using POC INRs (including self-testing/self-monitoring), via an anticoagulation clinic, ensure: • Check for concordance versus venous INRs (ie, <0.5 INR unit difference) before use for monitoring: initially on three occasions when venous INR in therapeutic range, thereafter, suggest check concordance once every 6-12 months • Regular internal quality control: run at minimum when testing a new batch of test strips or if unexpectedly high or low INR • Regular external quality assessment |

| Chromogenic factor X | Chromogenic assay | ~40%–20% = INR 2.0-3.0 | • LA-independent measure of anticoagulant intensity • Therapeutic ranges not established • Poor utility at INRs >3.0 (equivalent to chromogenic factor X < 12 IU/dL; ie, inverse relationship) • Not widely available or practicable for routine use • Could assist (1) in INR monitoring when prolonged INR before warfarin/VKA; or (2) if recurrent thrombotic event while on apparently therapeutic VKA anticoagulation |

| Thrombin generation | Fluorogenic substrate, continuous measurement of TG | Therapeutic range not established | • ETP and peak TG showed significant inverse correlations with INR in non-APS and APS patients24 • A subgroup of APS patients with increased peak TG, despite therapeutic INR and CFX, suggests that TG might identify an ongoing prothrombotic state24 • The use of TG remains limited to specialized laboratories due to lack of standardization and established therapeutic ranges |

ETP, endogenous thrombin potential.

Adapted from Table 1 in Cohen et al.52

Other assays may have utility in monitoring warfarin in LA-positive patients. CFX levels have an inverse relationship with INR17,24 and could provide an LA-independent assessment of warfarin anticoagulation intensity (eg, when the baseline INR is prolonged or when recurrent thrombosis occurs while on apparently therapeutic VKA). However, this assay has limited applicability, as therapeutic ranges are not established and the assay is not well standardized or widely available for routine use. Thrombin generation (TG) parameters, endogenous thrombin potential and peak TG, showed significant inverse correlations with INR in APS patients on warfarin, and might inform anticoagulation intensity.24 However, TG assays, limited to specialized laboratories, lack standardization and established therapeutic ranges. Table 1 summarizes key information relating to monitoring tests for warfarin/VKA in patients with APS.

CLINICAL CASE 1 (continued)

INR concordance assessment of venous versus POC, undertaken when the venous INR was therapeutic, demonstrated discordance, with venous INRs 2.1, 1.9, and 2.6; and POC INRs 2.9, 3.1, and 3.6, respectively, on 3 consecutive occasions. The patient was therefore advised to continue with venous INRs. He had a recurrent left lower limb proximal DVT while on warfarin, with venous INRs >3.0 preceding the event. There was no evidence of an alternative cause for the DVT. The warfarin was transitioned to treatment dose enoxaparin 80 mg (1 mg/kg) every 12 hours.

Low-molecular-weight heparin for anticoagulant- refractory thrombotic APS

Should recurrent thrombosis occur while on high-intensity VKA, LMWH can be used.9 This approach is supported by limited evidence: in 2 small retrospective studies in patients with APS, 1/14 and 3/9, respectively, had recurrent thrombosis on LMWH after failing warfarin therapy.25,26 In a retrospective study, 70 patients with cancer and recurrent VTE on VKA were transitioned to standard therapeutic or higher intensity (120%-125% dose) LMWH. There was no VTE recurrence in 91% of those patients over 3 months.27 Prolonged LMWH use, between 3 and 24 months, decreases mean bone mineral density (BMD) by up to 4.8%,28 and patients should have their vitamin D status optimized and undergo BMD surveillance, with bone protection treatment as required.

CLINICAL CASE 2 (continued)

One year later, the patient reported that she was pregnant, at 4 weeks gestation. Warfarin was discontinued; subcutaneous split-dose enoxaparin, 60 mg in the morning and 40 mg in the evening every 12 hours (~1.5 mg/kg/d; weight 60 kg), was commenced once the INR fell to <2.0; and LDA was started a week later. The patient was maintained on adjusted dose enoxaparin during pregnancy, with a dose increment to 60 mg every 12 hours (~1 mg/kg twice daily; weight 65 kg) at 28 weeks gestation. A healthy boy infant, birth weight 3000 g, was delivered at 38 + 5 weeks gestation by vaginal delivery following elective induction of labor. Enoxaparin was transitioned back to warfarin 2 weeks after delivery.

Low-molecular-weight heparin during pregnancy

The management of pregnancy in women with thrombotic APS is aimed at preventing thrombosis and aPL-associated obstetric morbidity.1,2 In the general population, VTE risk is increased approximately 5-fold during pregnancy, peaking in the postpartum period.29 The overall absolute incidence of pregnancy-associated VTE is low (1.2 per 1000 pregnancies30); formal VTE risk assessment is required to identify individuals at increased risk who may benefit from antepartum/postpartum thromboprophylaxis.29,31 Women with a history of ischemic stroke are at increased risk of recurrent stroke during subsequent pregnancy/ puerperium: the absolute risk was 1.8% (95% CI, 0.5%-7.5%) in 1 retrospective study of 441 women.32 Thrombotic APS is a strong risk factor for pregnancy associated-VTE, with a Canadian population-based study finding that APS was associated with adjusted odds ratios of 12.9 (95% CI, 4.4-38.0) and 5.1 (95% CI, 1.8-14.3) for pregnancy-associated PE and DVT, respectively.33 A history of obstetric APS (OAPS) alone appears to confer relatively low risk: a pooled analysis of RCTs in women with LA/aCL and pregnancy morbidity showed no antenatal VTE among those in the aspirin or placebo arms (n = 310).34 Catastrophic APS (CAPS), a rare, life-threatening complication of APS, occurred in association with pregnancy in 8% (40/500) of cases within the international CAPS registry.35

The standard APS-directed treatment during pregnancy is LDA in combination with heparin. Unlike VKA and DOACs, LMWH and UFH do not cross the placenta and are not associated with embryo-fetal toxicity.36 LMWH is usually preferred to UFH, supported by general pregnancy guidance31,37 and limited data from randomized head-to-head studies38 in the context of OAPS. The recommended dose of LMWH is therapeutic4,31,39/intermediate31 intensity in thrombotic APS, and prophylactic intensity for those with OAPS alone.4,39 Limited data suggest that patients with a history of APS-related cerebrovascular events are at excess risk of recurrence during pregnancy,40,41 thus higher intensity LMWH may be considered. Heparin should be continued for a minimum of 6 weeks after delivery,4,31,39 or warfarin may be resumed for patients requiring long-term anticoagulation; both are safe in breastfeeding. There is uncertainty regarding other dosing considerations for therapeutic-intensity LMWH in pregnant patients with APS: once daily vs twice daily split dose; dose adjustment according to weight gain or anti-Xa monitoring.4,39 Recommendations from general pregnancy guidance vary.37,42

Major bleeding rates during antithrombotic treatment in pregnancy appear to be low: 3% within a retrospective analysis of 177 pregnancies in women with APS receiving LDA and/or heparin, with 48% (85/177) of all cases receiving LDA and therapeutic-intensity heparin.43

Low-molecular-weight heparin versus unfractionated heparin

LMWH has more predictable pharmacokinetics, higher bioavailability and a longer half-life than UFH, via subcutaneous administration, which permits weight-based dosing without coagulation monitoring.36 Studies in the general population (of acute VTE patients) indicate favorable efficacy and bleeding risk.44 LMWH is associated with a lower risk of heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT) compared to UFH, with platelet count monitoring only required after major surgery or trauma.45 Important considerations for the dosing and monitoring of LMWH and UFH are summarized in Table 2 and Table 3, respectively.

Low-molecular-weight heparin in patients with antiphospholipid syndrome

| Clinical indications for consideration of LMWH in patients with APS: • Anticoagulant-refractory thrombotic APS (anticoagulant is warfarin/VKA) • CAPS • Pregnancy • Warfarin/VKA intolerance • Bleeding concerns with warfarin/VKA Dosing: Weight-based dosing, without anti-Xa monitoring, is generally appropriate Careful review of LMWH dose during periods of thrombocytopenia | Monitoring: Monitor platelets for HIT: • during LMWH use after major surgery or major trauma (intermediate risk, 0.1%-1.0%) • not required in medical or obstetric patients or after minor surgery or trauma (low risk, <0.1%)45 ASH VTE guidance suggests (with low/very low certainty) against anti-Xa monitoring in: • pregnancy • renal impairment (creatinine clearance <30mL/min), favoring fixed dose reduction per manufacturer's recommendations • obesity, favoring dosing by actual body weight (uncapped) Limitations of chromogenic anti-Xa assays for monitoring LMWH include: • clinical utility uncertain • not universally available • suboptimal reproducibility and interlaboratory variation |

| Clinical indications for consideration of LMWH in patients with APS: • Anticoagulant-refractory thrombotic APS (anticoagulant is warfarin/VKA) • CAPS • Pregnancy • Warfarin/VKA intolerance • Bleeding concerns with warfarin/VKA Dosing: Weight-based dosing, without anti-Xa monitoring, is generally appropriate Careful review of LMWH dose during periods of thrombocytopenia | Monitoring: Monitor platelets for HIT: • during LMWH use after major surgery or major trauma (intermediate risk, 0.1%-1.0%) • not required in medical or obstetric patients or after minor surgery or trauma (low risk, <0.1%)45 ASH VTE guidance suggests (with low/very low certainty) against anti-Xa monitoring in: • pregnancy • renal impairment (creatinine clearance <30mL/min), favoring fixed dose reduction per manufacturer's recommendations • obesity, favoring dosing by actual body weight (uncapped) Limitations of chromogenic anti-Xa assays for monitoring LMWH include: • clinical utility uncertain • not universally available • suboptimal reproducibility and interlaboratory variation |

Monitoring of unfractionated heparin in antiphospholipid syndrome patients

| Regular laboratory monitoring of IV UFH is essential due to pharmacokinetic unpredictability. | |||||

Platelet count monitoring is indicated in all patients receiving UFH due to the increased risk of HIT:

| |||||

| Monitoring test . | Dose . | Target range . | Points to note . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chromogenic anti-Xa assay | IV bolus of UFH 5000 units/75 units/kg (10 000 units for severe PE), then 15-25 units/kg/hour, by continuous IV infusion, dose adjusted | 0.3-0.7 IU/mL36 | • Use anti-Xa assay when baseline aPTT prolonged (eg, due to LA effect) • Anti-Xa preferred as first line assay for UFH monitoring in APS patients, as it is unaffected by LA or acute phase reactants (unlike aPTT) • In CAPS patients in the acute situation, anti-Xa is appropriate for UFH monitoring and may aid interpretation of concomitant aPTT • The anti-Xa assay should be standardized versus the international standard for UFH • Limitations of anti-Xa assays include: not universally available, suboptimal reproducibility and interlaboratory variation | ||

| aPTT | aPTT therapeutic range corresponding to UFH levels of 0.3 to 0.7 IU/mL anti-Xa activity36 | • For UFH monitoring by aPTT, a relatively LA-insensitive aPTT reagent is required • Avoid use of aPTT for monitoring UFH if baseline aPTT is prolonged • The aPTT may be unreliable in the acute phase situation (eg, CAPS: factor VIII may shorten aPTT; CRP may prolong aPTT; anti-Xa assay is uninfluenced by these factors) • aPTT therapeutic range should be locally adapted to the responsiveness of the reagent and coagulometer used | |||

| ACT | In non-APS patients undergoing CPB, generally a dose of UFH of ~300-400 IU/kg is administered prior to CPB with additional boluses given as required | • In non-APS patients: ACT in a non-anticoagulated patient is ~107 s ± 13 s • During CPB, UFH is titrated to maintain an ACT of 400-600 s | • The ACT is widely used to monitor UFH during CPB • The ACT is a phospholipid-dependent test and may be prolonged by LA • Reported modifications for use in patients with APS: ○ target clotting time twice the baseline ACT ○ measure heparin concentrations by automated protamine titration device ○ use patient-specific heparin-ACT titration curves (preoperative in vitro derived) ○ ACT coupled with thromboelastography | ||

| Regular laboratory monitoring of IV UFH is essential due to pharmacokinetic unpredictability. | |||||

Platelet count monitoring is indicated in all patients receiving UFH due to the increased risk of HIT:

| |||||

| Monitoring test . | Dose . | Target range . | Points to note . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chromogenic anti-Xa assay | IV bolus of UFH 5000 units/75 units/kg (10 000 units for severe PE), then 15-25 units/kg/hour, by continuous IV infusion, dose adjusted | 0.3-0.7 IU/mL36 | • Use anti-Xa assay when baseline aPTT prolonged (eg, due to LA effect) • Anti-Xa preferred as first line assay for UFH monitoring in APS patients, as it is unaffected by LA or acute phase reactants (unlike aPTT) • In CAPS patients in the acute situation, anti-Xa is appropriate for UFH monitoring and may aid interpretation of concomitant aPTT • The anti-Xa assay should be standardized versus the international standard for UFH • Limitations of anti-Xa assays include: not universally available, suboptimal reproducibility and interlaboratory variation | ||

| aPTT | aPTT therapeutic range corresponding to UFH levels of 0.3 to 0.7 IU/mL anti-Xa activity36 | • For UFH monitoring by aPTT, a relatively LA-insensitive aPTT reagent is required • Avoid use of aPTT for monitoring UFH if baseline aPTT is prolonged • The aPTT may be unreliable in the acute phase situation (eg, CAPS: factor VIII may shorten aPTT; CRP may prolong aPTT; anti-Xa assay is uninfluenced by these factors) • aPTT therapeutic range should be locally adapted to the responsiveness of the reagent and coagulometer used | |||

| ACT | In non-APS patients undergoing CPB, generally a dose of UFH of ~300-400 IU/kg is administered prior to CPB with additional boluses given as required | • In non-APS patients: ACT in a non-anticoagulated patient is ~107 s ± 13 s • During CPB, UFH is titrated to maintain an ACT of 400-600 s | • The ACT is widely used to monitor UFH during CPB • The ACT is a phospholipid-dependent test and may be prolonged by LA • Reported modifications for use in patients with APS: ○ target clotting time twice the baseline ACT ○ measure heparin concentrations by automated protamine titration device ○ use patient-specific heparin-ACT titration curves (preoperative in vitro derived) ○ ACT coupled with thromboelastography | ||

Adapted from Table 3 in Cohen et al.52

Unfractionated heparin: role in thrombotic APS

Intravenous (IV) UFH, owing to its rapid onset/offset of action and reversibility with protamine sulphate, has been suggested as initial therapy for high-risk pulmonary embolism (particularly in thrombolysis cases),46 and in the setting of severe renal impairment,36,46 risk of severe bleeding, or imminent surgery. UFH is standard treatment during cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) surgery.47

Notably, in the CAPS Registry, anticoagulation was administered in 427/500 (82%) patients, mostly as intravenous UFH followed by VKA. Anticoagulation, particularly UFH, has been recommended for use in CAPS as part of “triple therapy” (anticoagulation, glucocorticoids, and plasma exchange/intravenous immunoglobulins), based on meta-analyses of mostly CAPS registry-based studies that suggest reduced mortality (anticoagulation: 2 studies, N = 325, OR 0.18, 95% CI 0.09-0.38; triple therapy: 4 studies, N = 357, OR 0.51, 95% CI 0.27-0.95).5

In our practice, LMWH is the heparin agent of choice outside of exceptional circumstances.

Monitoring of low-molecular-weight heparin

The aPTT is unsuitable for monitoring LMWH. Chromogenic anti-Xa activity is used where monitoring is required,48 including in patients with APS. Therapeutic intensity reference ranges depend on dosing regimen (once daily vs twice daily) and timing of level in relation to last administered dose (peak or trough levels).48 Unlike aPTT, the chromogenic anti-Xa assay is unaffected by LA, and the acute phase reactants C-reactive protein (CRP) and factor VIII (FVIII).

Important limitations of LMWH monitoring include suboptimal reproducibility and interlaboratory standardization,49 and correlations of anti-Xa activity with efficacy and with safety are weak. The utility of anti-Xa monitoring of therapeutic-intensity LMWH is uncertain. ASH guidance suggests (with low/very low certainty) against anti-Xa monitoring in (1) pregnancy37; (2) renal impairment (creatinine clearance <30 mL/min), favoring fixed dose reduction per manufacturer's recommendations20; and (3) obesity, favoring dosing by actual body weight (uncapped).20

For pregnant women with thrombotic APS receiving therapeutic-intensity LMWH, we use twice-daily (split) dosing, with anti-Xa monitoring. This is because of the potentially altered pharmacokinetics of LMWH during pregnancy (ie, increased volume of distribution and renal clearance) and the backdrop of increased thrombotic risk.33,40,41 LMWH dosing requires careful review and potential adjustment during periods of thrombocytopenia.

Monitoring of unfractionated heparin

The pharmacokinetic unpredictability of therapeutic intravenous UFH necessitates regular monitoring using an aPTT or anti-Xa assay.48 In patients with APS, the aPTT may be unreliable due to LA-induced prolongation and consequent risk of overestimating UFH effect. Use of an LA-insensitive aPTT reagent is recommended. The anti-Xa assay, insensitive to LA effect, may be preferable to the aPTT for UFH monitoring, and should be used when there is baseline aPTT prolongation.48 The aPTT may also give unreliable results due to effects of acute phase reactants: raised factor VIII may shorten the aPTT, leading to an underestimation of the UFH anticoagulation effect36; CRP interferes with the aPTT, prolonging clotting times proportional to CRP concentration and depending on the type of the aPTT reagent.50 Platelet count monitoring is recommended in all patients receiving UFH due to the higher risk of HIT.45

Conclusions

Anticoagulant monitoring in APS patients necessitates strategies to circumvent LA-induced effects on phospholipid-dependent coagulation tests. For VKA monitoring, venous INRs using an LA-insensitive thromboplastin, instrument-specific ISI, and local INR calibration can ensure accurate INRs in the majority of patients. POC INRs may be suitable for some APS patients who exhibit concordance. Although not standardized, CFX may provide additional information. LMWH may be monitored by chromogenic anti-Xa assay, which is unaffected by LA, though the clinical utility is uncertain. The aPTT may be unreliable due to LA-induced effects in patients with APS; thus, anti-Xa assays may be required to monitor UFH.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure

Prabal Mittal: no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Zara Sayar: no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Hannah Cohen reports, outside the submitted work, honoraria from UCB Biopharma and Technoclone (paid to UCL Hospital Charity) and from GSK and being an advisory board member for Roche and argenx.

Off-label drug use

Prabal Mittal: The use of high dose rivaroxaban in thrombotic APS patients, under investigation in a clinical trial, is noted.

Zara Sayar: The use of high dose rivaroxaban in thrombotic APS patients, under investigation in a clinical trial, is noted.

Hannah Cohen: The use of high dose rivaroxaban in thrombotic APS patients, under investigation in a clinical trial, is noted.