Abstract

Transplant-associated thrombotic microangiopathy (TA-TMA) after hematopoietic cell transplantation is characterized by microangiopathic hemolytic anemia (MAHA) with persistent schistocytosis, elevated markers of hemolysis, thrombocytopenia, and microvascular thrombosis leading to ischemic injuries in the kidneys and other organs. The initial evaluation of the disease requires confirmation of non-immune MAHA and careful examination of known secondary causes of TMA. Due to increased likelihood of long-term renal failure and overall mortality, a rapid diagnosis and treatment of the underlying trigger is needed. However, the diagnostic criteria proposed to define TA-TMA remain insufficient. sC5b9, the soluble form of the membrane attack complex of the terminal complement pathway, is the most studied prognostic biomarker for the disease, though its sensitivity and specificity remain suboptimal for clinical use. Current evidence does not support the cessation of calcineurin inhibitors without cause or the use of therapeutic plasma exchange. Many recent single-arm studies targeting the complement pathway inhibition have been reported, and larger randomized controlled trials are ongoing. This review aims to provide an evidence-based discussion from both adult and pediatric perspectives on the advances and conundrums in TA-TMA diagnosis and treatment.

Learning Objectives

Compare and contrast the various diagnostic criteria used for TA-TMA

Evaluate recent literature and ongoing trials for TA-TMA–directed therapy

Introduction

Transplant-associated thrombotic microangiopathy (TA-TMA) is a systemic complication that can arise after hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT). As part of the TMA family that also includes thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP) and complement-mediated hemolytic uremic syndrome (CM-HUS), the disease usually manifests with uncontrolled microangiopathic hemolytic anemia (MAHA) with persistent schistocytosis, elevated markers of hemolysis, thrombocytopenia, and microvascular thrombosis leading to ischemic injuries in the kidneys and other organs.1 While significant debate remains, TA-TMA is generally considered a secondary TMA and a common final pathway resulting from a multitude of potential triggers.2-4

The understanding of TA-TMA has evolved significantly over the past 20 years. An initial systematic review in 2004 reported a pooled incidence of 0.5% to 63.6% and a case fatality rate of 0% to 100%.5 In contrast, a recent meta- analysis in 2020 narrowed the disease incidence to 12% (95% CI 9%-16%) in the first year post-transplant.6 Estimated case fatality has ranged from 30% to 50% depending on the inclusion and exclusion criteria.2,5,7,8 This review aims to provide an evidence-based discussion from both adult and pediatric perspectives on the advances and conundrums in TA-TMA diagnosis and treatment.

CLINICAL CASE

A 21-year-old man with a history of pre-B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia and type 1 diabetes who received a matched unrelated donor transplant presented for day 60 outpatient HCT follow-up. He had acute anemia (hemoglobin of 6.1 g/dL) and thrombocytopenia (platelet count 20 x 103/uL), associated with a >2x increase in creatinine (1.33 mg/dL) and 3+ proteinuria. Further hemolytic workup was notable for elevated lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) of 744 U/L, an undetectable haptoglobin, and 3%-4% schistocytes per high-power field on peripheral smear. The level of soluble C5b9 (sC5b9) of the terminal complement pathway was initially in the normal range.

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

The clinical manifestation varies by the study population and disease definition. Table 1 summarizes clinical manifestations reported in retrospective cohorts that include at least 50 TA-TMA patients or prospective studies since 2014. The median time to TA-TMA onset is generally 30 to 60 days post-transplant. In both adult and pediatric cohorts, there is significant renal involvement at disease onset, with 40%-60% having acute kidney injury (AKI) and 70% to 80% with proteinuria associated with hypertension.2,9-12 TA-TMA is also associated with higher risk of long-term chronic kidney disease and end-stage renal disease.13-15 Neurologic manifestation such as encephalopathy or seizure may occur in 25% of cases.2,9-11,16 Finally, acute GVHD often precedes development of TA-TMA and is a common risk factor ranging from 38% to 49% of patients.2,9-12,16 Differentiating whether gastrointestinal bleeding11 is from TA-TMA or GVHD can be challenging. Adult and pediatric literature differ in the reports of cardiopulmonary presentations. While diffuse alveolar hemorrhage (DAH) has been reported in 9% to 17% of both adult and pediatric patients within 2 weeks of disease onset,2,17 pericardial effusion and pulmonary hypertension are reported in up to 20% of pediatric patients only.11,12

Common clinical manifestations of TA-TMA

| . | Adulta . | Pediatrica . |

|---|---|---|

| Renal | ||

| Acute kidney injury | 41% | 61% |

| Hypertension | 32% | Common (% not reported) |

| Proteinuria >30 mg/dL | 68% | 76% |

| Neurologic | ||

| Encephalopathy, confusion, or seizure | 25% | 23% |

| Gastrointestinal | ||

| Preceding/concurrent acute GVHDb | 49% | 38% |

| Gastrointestinal bleeding | 8% | 25% |

| Cardiopulmonary | ||

| Diffuse alveolar hemorrhage | 9% | 17%c |

| Pericardial effusion | Not reported | 18% |

| Pulmonary hypertension | Not reported | 7% |

| . | Adulta . | Pediatrica . |

|---|---|---|

| Renal | ||

| Acute kidney injury | 41% | 61% |

| Hypertension | 32% | Common (% not reported) |

| Proteinuria >30 mg/dL | 68% | 76% |

| Neurologic | ||

| Encephalopathy, confusion, or seizure | 25% | 23% |

| Gastrointestinal | ||

| Preceding/concurrent acute GVHDb | 49% | 38% |

| Gastrointestinal bleeding | 8% | 25% |

| Cardiopulmonary | ||

| Diffuse alveolar hemorrhage | 9% | 17%c |

| Pericardial effusion | Not reported | 18% |

| Pulmonary hypertension | Not reported | 7% |

Clinical manifestation in selective retrospective cohorts with at least 50 TA-TMA patients or prospective studies 2014-2023: adult—Gavriilaki 2018 (n = 116), Kraft 2019 (n = 65), Li 2019 (n = 192), Heybeli 2020 (n = 84); pediatric—Jodele 2014 (n = 39), Dandoy 2021 (n = 98), Agarwal 2022 (n = 58). Studies that presented data on all TA-TMA patients at initial diagnosis (instead of selective high-risk or low-risk subset) were included.

Either grade 2 to 4 or 1 to 4 depending on the study included; not all GVHDs were gastrointestinal.

Number of patients with DAH within 2 weeks of TA-TMA diagnosis.

Risk factors and pathophysiology

The pathophysiology of TA-TMA centers on endothelial damage. A multi-hit hypothesis involving an insult from conditioning regimen followed by post-transplant vascular and infectious complications has been postulated.18,19 In a recent systematic review, clinical risk factors that are present in multiple studies include baseline factors such as previous HCT, myeloablative conditioning, mismatched donor, older age, and female sex, as well as time-dependent factors such as grade II to IV acute GVHD, selective viral infections (ie, BK viremia), angioinvasive fungal infections (ie, aspergillosis), and high-dose sirolimus.6

While complement dysregulation and overactivation frequently occur in TA-TMA, it remains less clear if there is a genetic predisposition similar to CM-HUS with underlying alterations in complement genes. The best supportive evidence is observed from a next-generation sequencing–based rare variant genetic association study by Jodele et al in 2014, where the authors found that complement gene mutations occurred in 65% (n = 22/34) of pediatric and adolescent TA-TMA patients vs 9% (n = 4/43) of post-transplant controls.20 However, this finding has not been replicated in other pediatric cohorts, and the association is less clear in adults. In a next-generation sequencing study comparing 40 TA-TMA adult patients with 40 post- transplant controls and 18 healthy donors, Gavriilaki et al found distinct complement gene variants in transplant vs healthy donors; however, the difference was less apparent between TA-TMA and post-transplant controls.21 Among those with rare variants, the authors reported statistically significant but numerically small differences in normalized variant counts for ADAMTS13 (2 vs 1), CD46 (1 vs 0), CFH (2 vs 1), and CFI (1 vs 0). In a subsequent whole-exome sequencing study conducted in 100 TA-TMA adults vs 98 post-transplant controls, Zhang et al examined rare variant associations in 5 prespecified genetic pathways.22 In this study, 29% (n = 29/100) of TA-TMA patients and 33% (n = 33/98) of post-transplant controls had at least 1 rare functional variant among complement genes (p = 0.43). It is important to note that rare variants in complement genes are not specific for TA-TMA. Mutations have been reported in other populations, including 29% of patients with systemic lupus erythematosus, 22% of patients with antiphospholipid syndrome, and even 23% of healthy controls.23

Similarly, there are no blood biomarkers that can definitively diagnose the disorder. sC5b9, the soluble form of the membrane attack complex of the terminal complement pathway, has been implicated in multiple small studies to have diagnostic, prognostic, and risk implications in TA-TMA.11,24-30 Two studies with 20 patients total showed that sC5b9 elevation has 100% sensitivity to predict later development of TA-TMA, but with specificity of only 53% and 61%.25,26 Serial measurement of sC5b9 has also shown significant intrapersonal variability without uniform cut-offs.29,31 Furthermore, sC5b9 is difficult to measure as it can be falsely elevated with improper sample handling, which could lead to over- or underdiagnosis. The alternative complement pathway marker Ba has also shown elevation in patients with TA-TMA compared with controls and can be predictive of later development of TA-TMA,31-33 but again lacking specificity. Other potential biomarkers noted in the literature include von Willebrand factor,28,29,34 Bb C3b and CH50,27 sVCAM-1,24 ANG-2,29 thrombomodulin,24,35 neutrophil extracellular traps,36 heme oxygenase 1,37 and ST2.35,38 In a recent systematic review, a meta-analysis could not be performed due to significant heterogeneity between the available biomarker studies for TA-TMA.39 Therefore, there is not a singular pathognomonic biomarker for TA-TMA diagnosis.

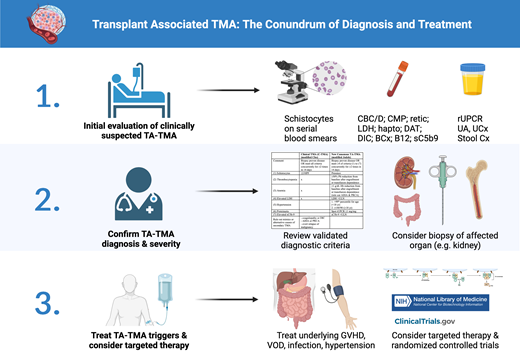

Initial evaluation for TA-TMA

A high index of clinical suspicion is required since TA-TMA can share common presentations with several other post-transplant complications, such as acute GVHD and veno-occlusive disease (VOD).40 The initial workup for all suspected TMAs starts with confirmation of new and persistent schistocytosis on blood smear (>1% or >2 per high-power field) along with new onset of thrombocytopenia and nonimmune hemolytic anemia. While schistocytosis may not be apparent initially, especially in pediatric patients,1 serial examination usually reveals its development as other TMA-like symptoms arise.31 All except the recent TA-TMA consensus diagnostic criteria require the presence of schistocytosis for formal diagnosis.41-44 Additional diagnostic workup is listed in Table 2. It is important to exclude autoimmune or alloimmune hemolysis (strongly positive direct antiglobulin test or circulating antibody), especially in patients with known donor ABO mismatch.

Initial diagnostic workup in patients suspected of TA-TMA

| Test . | Indication . | Rationale . |

|---|---|---|

| CBC/diff, reticulocytes, BMP, LFT, total/direct bilirubin, LDH, haptoglobin | All patients | Confirm hemolysis, rule out red cell aplasia or aplastic anemia |

| Blood smear (serial) | All patients | Confirm presence & persistence of schistocytosis |

| DAT; IAT (ask for agglutination strength) | All patients | Rule out autoimmune or alloimmune hemolytic anemia |

| DIC panel (PT/PTT/INR, D-dimer, fibrinogen) | All patients | Rule out DIC |

| Infectious workup | All patients | Rule out infection/sepsis |

| Vitamin B12 | All patients | Rule out cobalamin deficiency-related pseudo-TMA |

| Urinalysis; spot rUPCR | All patients | Seek early renal organ damage (proteinuria) |

| sC5b9 assay | Suspected TA-TMA | Prognostic biomarker for TA-TMA |

| ADAMTS13; antinuclear antibody; lupus anticoagulant; anticardiolipin; beta-2-glycoprotein | Autoimmune history | Rule out TTP & other autoimmune causes (rare to occur first-time post-transplant without prior history) |

| Stool culture for Shiga toxin; gut biopsy | New diarrhea | Rule out ST-HUS |

| Bone marrow biopsy | Inappropriate hematopoiesis or circulating blasts | Rule out relapse of pre-transplant disease or graft failure |

| Kidney biopsy | New kidney injury | Confirm diagnosis of TMA on biopsy |

| Test . | Indication . | Rationale . |

|---|---|---|

| CBC/diff, reticulocytes, BMP, LFT, total/direct bilirubin, LDH, haptoglobin | All patients | Confirm hemolysis, rule out red cell aplasia or aplastic anemia |

| Blood smear (serial) | All patients | Confirm presence & persistence of schistocytosis |

| DAT; IAT (ask for agglutination strength) | All patients | Rule out autoimmune or alloimmune hemolytic anemia |

| DIC panel (PT/PTT/INR, D-dimer, fibrinogen) | All patients | Rule out DIC |

| Infectious workup | All patients | Rule out infection/sepsis |

| Vitamin B12 | All patients | Rule out cobalamin deficiency-related pseudo-TMA |

| Urinalysis; spot rUPCR | All patients | Seek early renal organ damage (proteinuria) |

| sC5b9 assay | Suspected TA-TMA | Prognostic biomarker for TA-TMA |

| ADAMTS13; antinuclear antibody; lupus anticoagulant; anticardiolipin; beta-2-glycoprotein | Autoimmune history | Rule out TTP & other autoimmune causes (rare to occur first-time post-transplant without prior history) |

| Stool culture for Shiga toxin; gut biopsy | New diarrhea | Rule out ST-HUS |

| Bone marrow biopsy | Inappropriate hematopoiesis or circulating blasts | Rule out relapse of pre-transplant disease or graft failure |

| Kidney biopsy | New kidney injury | Confirm diagnosis of TMA on biopsy |

BMP, basic metabolic panel; CBC/diff, complete blood count with differential; DAT, direct antiglobulin test (direct Coombs); DIC, disseminated intravascular coagulation; IAT, indirect antiglobulin test; INR, international normalized ratio; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; LFT, liver function tests; PT, prothrombin time; PTT, partial thromboplastin time; rUPCR, random urine protein creatinine ratio; ST-HUS, Shiga toxin hemolytic uremic syndrome; TTP, thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura.

Once MAHA is confirmed, the workup should focus on evaluating for causes of known secondary TMA, such as disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), severe sepsis, overt relapse of malignancy (bone marrow biopsy), severe vitamin B12 deficiency, Shiga toxin E. coli–associated HUS, and autoimmune diseases in selective scenarios. Additional tests to consider include urinalysis, random urine protein to creatinine ratio (rUPCR), and sC5b9, as these may be associated with poor survival.11,45 However, it is important to note that proteinuria is not specific for TA-TMA and may be present in up to 15% of patients post-transplant.46,47 Furthermore, sC5b9 is a send-out test in most institutions, requiring advanced coordination and planning, along with previously discussed limitations.

Finally, when there is ambiguity in clinical presentation, biopsy of the affected organ (most commonly kidney) should be considered. Characteristic findings of acute TMA on kidney biopsy, such as glomerular thrombi, capillary fibrinogen deposition, and endothelial swelling, can lead to early diagnosis and appropriate initiation of treatment. Alternatively, the lack of TMA on the biopsy can help establish alternative diagnosis and prevent unnecessary treatment.

Diagnostic dilemma

Despite recent advances in the understanding of TA-TMA, there are ongoing controversies regarding its diagnosis. Table 3 lists some commonly used diagnostic criteria. Older studies have mostly utilized either the BMT-CTN criteria focused on organ damage or the IWG criteria focused on high levels of schistocytosis.41,43 Since 2010, variations of the Cho criteria have been mostly used in adult literature.48 The clinical-TMA (C-TMA) criteria is one such modification from Cho that focuses on the concurrent and persistent schistocytosis, thrombocytopenia, anemia, and elevated LDH (MAHA) in addition to clinical diagnosis to rule out coagulopathy, DIC, autoimmune hemolytic anemia, or overt relapse of malignancy.2,31 In contrast, modifications of the Jodele criteria have been mostly used in pediatric studies.11 Recently, a consensus panel of experts from four international transplant societies have recommended the modified Jodele criteria for TA-TMA diagnosis in all patients.42 The new criteria define standard-risk TA-TMA as those having persistent presence in 4 of 7 clinical parameters (schistocytosis, thrombocytopenia, anemia, elevated LDH, hypertension, spot rUPCR, sC5b9), while high-risk TA-TMA is defined as having any additional high-risk features (C5b9 greater than ULN, rUPCR ≥1 mg/mg, LDH ≥2x ULN, grade 2 to 4 acute GVHD, viral infection, or any organ dysfunction). The consensus panel has clarified that thrombocytopenia and anemia should be considered after engraftment unless with prolonged transfusion dependence; however, the presence of schistocytes is no longer required. Notably, while the original Jodele definition relied solely on proteinuria, elevated sC5b9, and multiorgan failure as high-risk features, the new consensus criteria also include additional less specific features like GVHD, infection, or high LDH. Furthermore, while newly elevated blood pressure requiring 2+ antihypertensives was previously required, the new consensus definition only requires blood pressure >140/90 (adult) or >99th percentile (pediatric). These additional changes increase sensitivity at the expense of specificity.31

Variations in common diagnostic criteria used for TA-TMA diagnosis

| . | BMT-CTN . | IWG . | Clinical TMA (C-TMA) (modified Cho) . | New consensus TA-TMAd (modified Jodele) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Comment | Meeting all criteria | Meeting all criteria | Biopsy proven disease or meet all criteria concurrently for ≥2 times in 14 days | Biopsy proven disease or meet ≥4 of criteria (1) to (7) concurrently for ≥2 times in 14 days |

| (1) Schistocytesa | ≥2/HPF | ≥4% (8/HPF) | ≥2/HPF | Presence |

| (2) Thrombocytopenia | x | x | ≥50% Plt reduction from baseline after engraftment or transfusion dependence | |

| (3) Anemia | x | x | ≥1 g/dL Hb reduction from baseline after engraftment or transfusion dependence (rule out AIHA & PRCA) | |

| (4) Elevated LDH | x | x | xb | LDH > ULN |

| (5) Hypertension | 1. >99th percentile for age (<18 yr) 2. ≥140/90 (≥18 yr) | |||

| (6) Proteinuria | Spot rUPCR ≥1 mg/mg | |||

| (7) Elevated sC5b9 | sC5b9 > ULN | |||

| Low haptoglobin | x | |||

| Negative DAT (Coombs) | x | |||

| Renal or neurologic dysfunction | x | |||

| Rule out mimics or alternative causes of secondary TMAc | - Coagulopathy or DIC - AIHA or PRCA - Overt relapse of malignancy |

| . | BMT-CTN . | IWG . | Clinical TMA (C-TMA) (modified Cho) . | New consensus TA-TMAd (modified Jodele) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Comment | Meeting all criteria | Meeting all criteria | Biopsy proven disease or meet all criteria concurrently for ≥2 times in 14 days | Biopsy proven disease or meet ≥4 of criteria (1) to (7) concurrently for ≥2 times in 14 days |

| (1) Schistocytesa | ≥2/HPF | ≥4% (8/HPF) | ≥2/HPF | Presence |

| (2) Thrombocytopenia | x | x | ≥50% Plt reduction from baseline after engraftment or transfusion dependence | |

| (3) Anemia | x | x | ≥1 g/dL Hb reduction from baseline after engraftment or transfusion dependence (rule out AIHA & PRCA) | |

| (4) Elevated LDH | x | x | xb | LDH > ULN |

| (5) Hypertension | 1. >99th percentile for age (<18 yr) 2. ≥140/90 (≥18 yr) | |||

| (6) Proteinuria | Spot rUPCR ≥1 mg/mg | |||

| (7) Elevated sC5b9 | sC5b9 > ULN | |||

| Low haptoglobin | x | |||

| Negative DAT (Coombs) | x | |||

| Renal or neurologic dysfunction | x | |||

| Rule out mimics or alternative causes of secondary TMAc | - Coagulopathy or DIC - AIHA or PRCA - Overt relapse of malignancy |

Schistocyte is required in all definitions except the new consensus criteria.

Various adult cohorts have used different LDH threshold including 1.5x or 2x due to its lack of specificity.

No singular laboratory testing is sufficient for diagnosing mimics or alternative triggers for secondary TMA; clinical diagnosis is required.

High-risk TA-TMA in the new consensus criteria is defined as those meeting standard risk criteria plus any one of the following: sC5b9 >ULN, rUPCR ≥1 mg/mg, organ dysfunction, LDH ≥2x ULN, concurrent grade 2 to 4 acute graft-versus-host disease, concurrent viral infection.

AIHA, autoimmune hemolytic anemia; DIC, disseminated intravascular coagulation; Hb, hemoglobin; HPF, high-power field; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; Plt, platelet; PRCA, pure red cell aplasia; rUPCR, random urine protein creatine ratio; ULN, upper limit of normal; yr, year.

While TA-TMA may have been underdiagnosed in earlier years due to low clinical recognition, it is possible that we may be overdiagnosing the disease in recent years due to changes in the proposed diagnostic criteria. A recent systemic review and meta-analysis with 21 cohort studies over 17 years showed that the diagnostic criteria used was the most significant contributor to the discrepancy in TA-TMA incidence.6 For example, studies using modified Jodele, modified Cho, BMT-CTN, and IWG criteria had a pooled incidence of 17%, 13%, 10%, and 7%, respectively, within the first 6 to 12 months post-transplant. In contrast, a CIBMTR study inclusive of 23,665 allogeneic HCT recipients of all ages from 2008-2016 only reported an incidence of 2% for clinically diagnosed TA-TMA at 1 year.

Several retrospective and prospective studies also directly compared different diagnostic criteria in the same cohort (Table 4). Relying solely on clinical diagnosis, 3% of HCT patients would be diagnosed with TA-TMA in retrospective cohorts and 10% to 13% in prospective cohorts. When comparing different research diagnostic criteria, the C-TMA definition would classify 9% of adult2 and 16% to 20% of pediatric patients31,49 as TA-TMA, while the modified Jodele consensus criteria (4 of 7) would classify 36% to 47% of HCT recipients as TA-TMA in the same cohorts.31,49,50 Furthermore, nearly all patients meeting standard risk (n = 12) also met high risk (n = 10) for the new consensus definition in a small prospective pediatric cohort study.31 Prognostically, those meeting both C-TMA and modified Jodele high-risk criteria (n = 5) had a survival of 60% at 6 months, but those meeting only modified Jodele high-risk without C-TMA (n = 5) had a survival of 100% at 6 months. These findings highlight the challenge of providing a set of research diagnostic criteria for a clinically diagnosed disease. Application of the various diagnostic criteria in the context of a multicenter prospective cohort study is needed to clarify their utility, and additional modification to the new consensus criteria (eg, requiring 5/7 including schistocytosis) is likely needed for improved diagnostic and prognostic accuracy.

Studies comparing different diagnostic criteria for TA-TMA in the same cohort

| Study definition . | Adult TA-TMA incidence . | Pediatric TA-TMA incidence . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Empiric clinical diagnosis | Li 2009, Retrospective | 70/2145 (3%) | Schoettler 2020, Retrospective | 8/307 (3%) |

| C-TMA (modified Cho) | 192/2145 (9%) | 62/307 (20%) | ||

| New consensus (modified Jodele 4/7) | Not reported | 110/307 (36%) | ||

| Empiric clinical diagnosis | Vasu 2024, Prospective | 10/101 (10%) | Li 2023, Prospective | 4/32 (13%) |

| C-TMA (modified Cho) | Not reported | 5/32 (16%) | ||

| New consensus (modified Jodele 4/7) | 47/101 (47%) | 12/32 (38%) | ||

| Study definition . | Adult TA-TMA incidence . | Pediatric TA-TMA incidence . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Empiric clinical diagnosis | Li 2009, Retrospective | 70/2145 (3%) | Schoettler 2020, Retrospective | 8/307 (3%) |

| C-TMA (modified Cho) | 192/2145 (9%) | 62/307 (20%) | ||

| New consensus (modified Jodele 4/7) | Not reported | 110/307 (36%) | ||

| Empiric clinical diagnosis | Vasu 2024, Prospective | 10/101 (10%) | Li 2023, Prospective | 4/32 (13%) |

| C-TMA (modified Cho) | Not reported | 5/32 (16%) | ||

| New consensus (modified Jodele 4/7) | 47/101 (47%) | 12/32 (38%) | ||

Number of patients diagnosed with TA-TMA among total number of patients undergoing hematopoietic cell transplantation. The median follow-up duration varies by study from 100 days to 180 days.

Treatment approach

Currently, there are no existing FDA-approved therapies for TA-TMA. Therefore, patients should be considered for enrollment in a randomized clinical trial (Table 5). Due to the heterogeneity of diagnostic criteria and associated antecedent conditions, even untreated patients with TA-TMA have distinct prognostic outcomes.2 Furthermore, patients with TA-TMA can also spontaneously improve with appropriate management of the triggering disease. Therefore, patients should first be treated for underlying disease processes such as high trough levels of calcineurin inhibitors (CNI) or sirolimus (SIR), systemic infection, GVHD, VOD, and malignant hypertension that could trigger or exacerbate TA-TMA. While older guidelines have recommended trial of CNI or SIR cessation, this has not been found to be effective in several recent studies due to frequent concurrence of GVHD, except in instances with a dual CNI/SIR prophylaxis regimen with high trough levels.2,51,52

Selective studies evaluating TA-TMA therapies

| Published studies . | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drug . | Author . | Study type . | Number of patients . | Inclusion criteria . | Response . | Survival . |

| Eculizumab | Jodele 2020 | Retrospective, single institution | 64 | Children and young adults with hrTMA (concurrent proteinuria and elevated C5b9) and treated with eculizumab | 64% response 56% CR | OS 77% at 6 months |

| Zhang 2021 | Systemic review with retrospective studies | 116 (including 64 from above) | Studies that included patients diagnosed with TA-TMA and eculizumab used first- or second-line | 71% response 32% CR | OS 52% at last follow-up of each study | |

| Svec 2023 | Retrospective, multi-institution | 82 | Allogeneic transplant patients <18 years with TA-TMA diagnosed by the treatment center and treated with eculizumab | 48% response | OS 47% at 6 months | |

| Jodele 2024 | Prospective, single-arm, multi-institution (NCT03518203) | 21 | Children and young adults, at least 5 kg, meeting criteria for hrTMA (concurrent proteinuria and elevated C5b9) | 67% response 48% CR | OS 71% at 6 months | |

| Narsoplimab | Khaled 2022 | Prospective, single-arm, multi-institution (NCT02222545) | 28 | Adults 18 or older with persistent TA-TMA | 61% response | OS 68% at 100 days |

| Defibrotide | Yeates 2017 | Retrospective, multi-institution | 39 | Pediatric and adult patients who received defibrotide to treat TA-TMA | 77% response | OS 59%-64% at unspecified follow-up |

| Marinez-Munoz 2019 | Retrospective, single institution | 16 | Adult patients who underwent allogeneic HCT with a diagnosis of TA-TMA | 65% response | OS 59% at unspecified follow-up | |

| Published studies . | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drug . | Author . | Study type . | Number of patients . | Inclusion criteria . | Response . | Survival . |

| Eculizumab | Jodele 2020 | Retrospective, single institution | 64 | Children and young adults with hrTMA (concurrent proteinuria and elevated C5b9) and treated with eculizumab | 64% response 56% CR | OS 77% at 6 months |

| Zhang 2021 | Systemic review with retrospective studies | 116 (including 64 from above) | Studies that included patients diagnosed with TA-TMA and eculizumab used first- or second-line | 71% response 32% CR | OS 52% at last follow-up of each study | |

| Svec 2023 | Retrospective, multi-institution | 82 | Allogeneic transplant patients <18 years with TA-TMA diagnosed by the treatment center and treated with eculizumab | 48% response | OS 47% at 6 months | |

| Jodele 2024 | Prospective, single-arm, multi-institution (NCT03518203) | 21 | Children and young adults, at least 5 kg, meeting criteria for hrTMA (concurrent proteinuria and elevated C5b9) | 67% response 48% CR | OS 71% at 6 months | |

| Narsoplimab | Khaled 2022 | Prospective, single-arm, multi-institution (NCT02222545) | 28 | Adults 18 or older with persistent TA-TMA | 61% response | OS 68% at 100 days |

| Defibrotide | Yeates 2017 | Retrospective, multi-institution | 39 | Pediatric and adult patients who received defibrotide to treat TA-TMA | 77% response | OS 59%-64% at unspecified follow-up |

| Marinez-Munoz 2019 | Retrospective, single institution | 16 | Adult patients who underwent allogeneic HCT with a diagnosis of TA-TMA | 65% response | OS 59% at unspecified follow-up | |

| Ongoing clinical trials . | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drug . | Sponsor . | Study type . | Number of patients . | Inclusion criteria . | End points to collect . | |

| Ravulizumab | Alexion | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multi-institution (NCT04543591) | 106 estimated | 12 years of age or older, HCT in the last 12 months, TMA diagnosis for at least 72 hours, weighing 30 kg or greater | - TMA response at 26 weeks | - OS at 26 and 52 weeks - nonrelapse mortality at 26 and 52 weeks |

| Nomacopan | AKARI Therapeutics | Prospective, single-arm, multi-institution (NCT04784455) | 50 estimated | 6 months to 18 years of age, undergone HCT with a diagnosis of TA-TMA | - Transfusion independence by week 24 | - rUPCR 2 mg/mg or less at 24 weeks |

| Narsoplimab | Omeros | Prospective, single-arm, multi-institution (NCT05855083) | 18 estimated | Pediatric patients 28 days to <18 years of age with high-risk TMA | - % clinical response | - OS at 100 days after high-risk TMA diagnosis |

| Pegcetacoplan | Sobi | Prospective, single-arm, multi-institution (NCT05148299) | 12 estimated | Adults 18 years or older, with a diagnosis of TA-TMA, and with rUPCR 1 mg/mg or greater | - % clinical & TMA responses at 12 and 24 weeks | - OS at 100 days - OS 24 days from treatment start |

| Ongoing clinical trials . | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drug . | Sponsor . | Study type . | Number of patients . | Inclusion criteria . | End points to collect . | |

| Ravulizumab | Alexion | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multi-institution (NCT04543591) | 106 estimated | 12 years of age or older, HCT in the last 12 months, TMA diagnosis for at least 72 hours, weighing 30 kg or greater | - TMA response at 26 weeks | - OS at 26 and 52 weeks - nonrelapse mortality at 26 and 52 weeks |

| Nomacopan | AKARI Therapeutics | Prospective, single-arm, multi-institution (NCT04784455) | 50 estimated | 6 months to 18 years of age, undergone HCT with a diagnosis of TA-TMA | - Transfusion independence by week 24 | - rUPCR 2 mg/mg or less at 24 weeks |

| Narsoplimab | Omeros | Prospective, single-arm, multi-institution (NCT05855083) | 18 estimated | Pediatric patients 28 days to <18 years of age with high-risk TMA | - % clinical response | - OS at 100 days after high-risk TMA diagnosis |

| Pegcetacoplan | Sobi | Prospective, single-arm, multi-institution (NCT05148299) | 12 estimated | Adults 18 years or older, with a diagnosis of TA-TMA, and with rUPCR 1 mg/mg or greater | - % clinical & TMA responses at 12 and 24 weeks | - OS at 100 days - OS 24 days from treatment start |

CR, complete response; HCT, hematopoietic cell transplantation; hrTMA, high-risk TMA; OS, overall survival; rUPCR, random urine protein to creatinine ratio.

In addition to best supportive care, the empiric treatment for high-risk TA-TMA with the most robust data is eculizumab, a monoclonal antibody that inhibits the cleavage of C5, preventing activation of the terminal complement pathway and formation of C5b9. In a systematic review and meta-analysis of 116 adult and pediatric patients from 6 studies, the authors reported an overall survival of 52% after eculizumab initiation.53 In a more recent retrospective study from 82 pediatric patients from 29 European HCT centers, the authors reported a similar overall survival of 47.1% at 6 months after eculizumab initiation.54 In contrast, a retrospective study by Jodele et al with 64 pediatric patients with high-risk TA-TMA (5 of 7 features with concurrent proteinuria and elevated C5b9) showed an overall survival of 77% at 6 months.55 Subsequently, a prospective study by the same authors showed that early therapy with eculizumab using loading, induction, and maintenance phases similarly improved outcomes and organ dysfunction in 21 high-risk pediatric TA-TMA patients, with an overall survival of 71% at 6 months.12 Of note, the poor survival outcome of 25% at 6 months in the frequently cited historical comparison arm was from a previous study of 12 pediatric patients diagnosed with TA-TMA using the Cho criteria in addition to presence of proteinuria and elevated sC5b9.11 More recent pediatric cohorts using the modified Jodele TA-TMA diagnostic criteria reported a 6-month survival approaching 70% among those with proteinuria, with or without eculizumab.12 Similarly, a different prospective pediatric cohort study noted that the diagnostic criteria used, regardless of eculizumab treatment, had the most significant association with patient survival (30% vs 100% at 6 months).31 These findings highlight the challenge of assessing treatment response in single-arm studies due to the possibility of selection bias. Furthermore, while hematologic parameters often improve after eculizumab initiation, recovery of organ dysfunctions such as acute and chronic kidney injury has significantly higher variabilities. While there are no ongoing prospective clinical trials for eculizumab, ravulizumab is a long- acting anti-C5 monoclonal antibody being evaluated by a current phase 3 randomized trial (NCT04543591).

Other anticomplement agents under investigation for TA-TMA treatment include narsoplimab, pegcetacoplan, and nomacopan. Narsoplimab is a monoclonal antibody that inhibits the mannan-binding lectin-associated serine protease-2 of the lectin complement pathway. A prospective, single-arm, phase 2 trial using narsoplimab for TA-TMA treatment in adults showed an overall survival of 68% at 100 days after diagnosis,56 and there is an ongoing prospective pediatric study (NCT05855083). Nomacopan is a recombinant small-protein inhibitor of C5 undergoing a phase 3 open-label trial (NCT04784455). Pegcetacoplan is a cyclic inhibitor of complement component C3 and is currently being evaluated for TA-TMA treatment with a phase 2 trial (NCT05148299).

Noncomplement agents for TA-TMA that have been used in the past include plasma exchange and defibrotide. Plasma exchange used to be the mainstay of therapy but has fallen out of favor after multiple studies showed poor response rates and high mortality.57 Defibrotide is a polydeoxyribonucleotide approved for the treatment of VOD; it induces vasodilation and reduces inflammation of the endothelium. Studies showed initial TA-TMA response rates of approximately 60%, but unfortunately these were not sustained.58,59 There is an ongoing phase 2 trial (NCT06182410) assessing defibrotide for prophylaxis of TA-TMA in pediatric patients with high-risk neuroblastoma receiving tandem transplants.

CLINICAL CASE CONCLUSION AND FUTURE DIRECTIONS

The patient was observed closely for 1 week, and sC5b9 on repeat was elevated at 310 ng/mL. A renal biopsy confirmed TA-TMA. He was started on eculizumab at standard weight-based weekly induction when hemolysis did not improve with best supportive care. After initial induction, the patient continued to receive eculizumab every 14 days, dosed by trough, with adequate suppression of CH50 and sC5b9 levels. The hematologic microangiopathy resolved after 2 months, but he was continued on eculizumab for a total of 6 months with the goal of improving his renal function. Unfortunately, his kidney function never recovered, and he ultimately developed end-stage kidney disease.

The understanding and management of TA-TMA have improved significantly over the past decade; however, additional work is needed to resolve the diagnostic and treatment conundrums and bridge the gap between adult and pediatric HCT treatment centers. Multicenter prospective cohort studies are needed to provide additional testing and fine-tuning of the recent consensus diagnostic criteria. Furthermore, identification of specific and rapid biomarkers is needed to accurately diagnose and distinguish TA-TMA, acute GVHD, and VOD. Finally, there is a significant and urgent need for both adult and pediatric transplant communities to participate in randomized, placebo-controlled trials to assess the efficacy of TA-TMA–directed therapy.

Acknowledgment

A.L., a Cancer Prevention Research Institute of Texas Scholar in Cancer Research, was supported by the Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas (RR190104), National Institute of Health NHLBI (K23 HL159271), NIH AIM-AHEAD (3OT2OD032581-01S1), American Society of Hematology (ASH) Scholar Award, and Conquer Cancer Foundation (ASCO) Career Development Award. Graphical abstract was created with BioRender.com under its Academic License Terms with Baylor College of Medicine.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure

Ang Li has no competing financial interests to declare.

Sarah E. Sartain received research funding from Alexion Discovery Partnerships.

Off-label drug use

Ang Li: All drugs discussed in this manusript are off-label as there is no FDA approved treatment for TA-TMA. The ones specifically mentioned include eculizumab, narsoplimab, defibrotide, ravulizumab, nomacopan, pegcetacoplan.

Sarah E. Sartain: All drugs discussed in this manusript are off- label as there is no FDA approved treatment for TA-TMA. The ones specifically mentioned include eculizumab, narsoplimab, defibrotide, ravulizumab, nomacopan, pegcetacoplan.