Abstract

Managing recurrent and refractory venous thromboembolism (VTE) in patients with cancer presents unique challenges. This review outlines the complexities and therapeutic strategies for recurrent VTE in cancer patients, which includes distinguishing thrombus acuity, differentiating between tumor and bland thrombi, and evaluating potential contributing factors including anticoagulant adherence, extrinsic tumor compression, drug interactions, and anticoagulant-specific considerations such as heparin-induced thrombocytopenia or antithrombin deficiency. Different anticoagulation strategies are discussed, including the administration of escalated-dose low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) as well as the indications and rationale for switching between direct oral anticoagulants or LMWH.

Learning Objectives

Develop a diagnostic strategy to identify etiologies for anticoagulant failure in patients with cancer

Recognize the therapeutic options in patients with refractory or recurrent thrombosis in cancer

CLINICAL CASE

A 65-year-old man with renal cell carcinoma metastatic to the pancreas, liver, and lungs, who is currently on nivolumab and ipilimumab, developed left calf pain with mild swelling. Ultrasound performed demonstrated a new occlusive thrombus involving the left common femoral vein. He was placed on therapeutic weight-based enoxaparin at 80 mg twice daily with improvement of lower extremity pain and swelling. On routine staging CT four months later, there was evidence of thrombus involving the infrarenal vena cava down to the bifurcation. The oncologist pages hematology to discuss switching from enoxaparin to apixaban for refractory thrombosis.

Background

High-quality evidence supports the use of either low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) or direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) for initial management of venous thromboembolism (VTE) in patients with malignancy. However, there is much less certainty regarding the appropriate management of patients who experience anticoagulation “failure” and are diagnosed with recurrent or progressive VTE. While uncommon, recurrent VTE was documented in 5% to 11% of patients enrolled in randomized trials during the initial 6 months of anticoagulation.1-4 The management of recurrent VTE in cancer can be challenging and is dependent on several factors, starting with a determination on whether the event truly represents an anticoagulant failure followed by an assessment of potential drivers of recurrent VTE.

Is this truly a new thrombotic event?

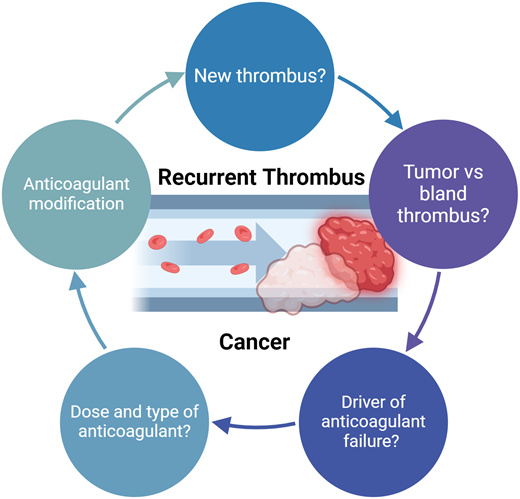

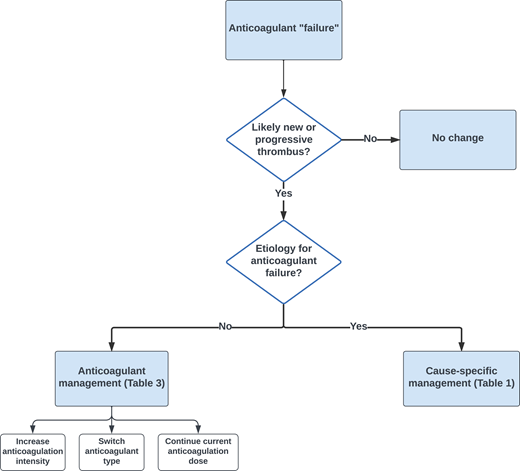

When considering how to approach the management of a patient with possible progressive or new thrombosis, the fundamental question is whether the event indeed represents anticoagulant failure (Figure 1). Approximately 25% of patients with cancer have concomitant evidence of deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE).5,6 It is not uncommon to later identify a PE through staging imaging in a patient diagnosed initially with DVT. Establishing whether these events represent breakthrough thrombosis can be challenging. The more straightforward cases are those where patients are acutely symptomatic, consistent with a new thrombotic event.

Evaluation and management of recurrent or refractory thrombosis in cancer.

Radiologic modalities can be useful in determining the acuity of DVT. Ultrasound features suggestive of an acute thrombus include evidence of a distended vein with hypoechoic thrombus that is either partially or completely noncompressible, without evidence of collateralization. Findings suggestive of a chronic thrombosis include lack of compressibility, intraluminal material that is nondeformable, and echogenic thrombus attached to the venous walls with corresponding wall thickening.7,8 Following an acute DVT, ultrasound abnormalities can persist in up to 60% of patients at one year.9 Identifying a new thrombus on the backdrop of a prior thrombus can be challenging, especially in the absence of an unequivocal new intraluminal filling defect. This is particularly problematic without access to baseline ultrasound imaging for direct comparison.8 Magnetic resonance imaging can be useful to differentiate an acute from chronic DVT. Magnetic resonance direct thrombus imaging (MRDTI), which measures the paramagnetic signal of methemoglobin in a fresh thrombus, is both sensitive and specific (≥95%) in distinguishing acute from recurrent ipsilateral DVT and has excellent inter-observer agreement.10-12 In a prospective study, MRDTI was performed in 305 patients with suspected recurrent ipsilateral DVT.13 Among the 122 patients with negative MRDTI who did not receive anticoagulation, there were 2 recurrent VTE (1.6%) at 3 months.13

Bland vs tumor thrombus

In cases of refractory or progressive thrombus, it is also important to distinguish a bland (fibrin) thrombus from an intravascular tumor, which is common in certain malignancies (Table 1). For instance, renal cell carcinoma commonly extends into the renal vein and inferior vena cava.14 Similarly, hepatocellular carcinoma can extend into portal and hepatic vasculature. Pancreatic carcinoma, Wilms' tumors, or retroperitoneal metastases occasionally extend into the inferior vena cava.15 Embolization of tumor thrombi to pulmonary vasculature is uncommon; in a series that reviewed over 600 autopsies, pulmonary tumor thrombus was present in 3% of cases.16 Rarely, angiosarcomas can also manifest with pulmonary artery involvement, mimicking pulmonary emboli on imaging.17 CT enhancement of filling defects contiguous with an adjacent mass supports the diagnosis of intravascular tumor. Instances without clear CT findings, either MRI or fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET), can be useful to distinguish a tumor from bland thrombi.18,19

Potential causes of anticoagulant failure in cancer

| Factors . | Details . | Management implications . |

|---|---|---|

| Anticoagulation adherence | • Noncompliance • Drug interruptions | • Counseling or alternative anticoagulant • Bridging or IVC filter if additional interruptions needed |

| Drug-drug interactions | • CYP3A4 inducers (Table 2) | • Alternative anticoagulant or increased doses of DOAC with Xa monitoring |

| Extrinsic compression | • Tumor compression • May-Thurner syndrome • Thoracic outlet obstruction | • Consideration of intravascular stenting |

| LMWH ineffectiveness | • Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia • Antithrombin deficiency (eg, asparaginase therapy) • Appropriate weight-based dosing | • Diagnosis of HIT mandates alternative anticoagulants such as direct thrombin inhibitors, DOAC, or fondaparinux • In cases of asparaginase deficiency, strategies include confirmation of therapeutic factor Xa levels, antithrombin repletion, alternative anticoagulants |

| DOAC ineffectiveness | • Antiphospholipid antibody syndrome • Reduced gastrointestinal absorption | • Warfarin for antiphospholipid antibody syndrome • LMWH if reduced absorption, rivaroxaban largely absorbed in the stomach |

| Intravascular | • Central venous catheter • IVC filter | • Consider removal of central venous catheter in setting of thrombosis |

| Tumor thrombus | • Renal cell carcinoma • Hepatocellular carcinoma • Thyroid cancer • Metastatic disease | • Tumor-directed therapy • Benefit of anticoagulation uncertain |

| Myeloproliferative neoplasms | • Polycythemia vera • Essential thrombocythemia | • Consideration of cytoreductive therapy with hydroxyurea ± aspirin |

| Factors . | Details . | Management implications . |

|---|---|---|

| Anticoagulation adherence | • Noncompliance • Drug interruptions | • Counseling or alternative anticoagulant • Bridging or IVC filter if additional interruptions needed |

| Drug-drug interactions | • CYP3A4 inducers (Table 2) | • Alternative anticoagulant or increased doses of DOAC with Xa monitoring |

| Extrinsic compression | • Tumor compression • May-Thurner syndrome • Thoracic outlet obstruction | • Consideration of intravascular stenting |

| LMWH ineffectiveness | • Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia • Antithrombin deficiency (eg, asparaginase therapy) • Appropriate weight-based dosing | • Diagnosis of HIT mandates alternative anticoagulants such as direct thrombin inhibitors, DOAC, or fondaparinux • In cases of asparaginase deficiency, strategies include confirmation of therapeutic factor Xa levels, antithrombin repletion, alternative anticoagulants |

| DOAC ineffectiveness | • Antiphospholipid antibody syndrome • Reduced gastrointestinal absorption | • Warfarin for antiphospholipid antibody syndrome • LMWH if reduced absorption, rivaroxaban largely absorbed in the stomach |

| Intravascular | • Central venous catheter • IVC filter | • Consider removal of central venous catheter in setting of thrombosis |

| Tumor thrombus | • Renal cell carcinoma • Hepatocellular carcinoma • Thyroid cancer • Metastatic disease | • Tumor-directed therapy • Benefit of anticoagulation uncertain |

| Myeloproliferative neoplasms | • Polycythemia vera • Essential thrombocythemia | • Consideration of cytoreductive therapy with hydroxyurea ± aspirin |

The value of anticoagulation in cases of an intravascular tumor is uncertain. In a retrospective cohort of 647 patients with renal cell carcinoma, 86 (13.3%) had evidence of tumor thrombus.14 The presence of tumor thrombi predicted a 6-fold-increased risk of developing VTE. Most of the VTE diagnosed in patients with a tumor thrombus were pulmonary emboli, suggesting that anticoagulation could be useful to prevent bland thrombus embolization. However, the cumulative incidence of VTE at 2 years among those with a tumor thrombus who received anticoagulation was not significantly lower, 17.6% compared with 23.9% without anticoagulation. Patients with tumor thrombosis also had more advanced disease and worse performance status, both of which are established risk factors for VTE. Bland thrombus associated with inferior vena cava tumor thrombus portends a worse prognosis.20 Accordingly, while the benefit of anticoagulation in patients with tumor thrombus is not established, based on the VTE risk profile of patients with tumor thrombus, it is my practice to at least consider prophylactic anticoagulation.

Potential explanations for recurrent or progressive VTE

In cases where there is evidence of progressive or recurrent VTE, management is dependent on determining the likely driver of anticoagulant “failure.” As shown in Table 1, there are a number of potential etiologies contributing to refractory VTE in patients with cancer:

Extrinsic compression of vessels by tumor masses is a common cause of refractory or recurrent thrombosis, often affecting the inferior vena cava or iliofemoral vessels due to pelvic or abdominal masses related to advanced prostate, gynecologic, colorectal, or renal cancers.21 The optimal management of external compression requires effective tumor-directed therapy (ie, radiation, chemotherapy). Especially in cases of refractory thrombosis with severe symptomatology, such as swelling, pain, or vascular compromise, intravascular stenting can be considered. While the comparative benefit relative to other treatment strategies (including anticoagulation alone) is not known, retrospective case series have documented clinical improvement in approximately 80% of cases.21 Mindful that placement of a stent often mandates ongoing anticoagulant therapy,22 we generally avoid placement in patients in cases where anticoagulation cannot be safely administered.

Anticoagulation adherence warrants consideration in cases of recurrent thrombosis. Approximately 1 in 5 patients discontinue LMWH early because of side effects or intolerance.23 Patients prescribed anticoagulation with DOACs tend to remain on anticoagulation longer, but on-therapy compliance appears to be similar to LMWH.24

Drug interruptions are also common in cancer, and we recently identified a high incidence of recurrent VTE when anticoagulation was interrupted in patients with acute VTE undergoing surgical procedures.25

Drug-drug interactions, namely CYP3A4 inducers, can reduce the therapeutic efficacy of DOACs (Table 2). DOACs are, in part, metabolized in the liver by CYP3A4 (edoxaban 27%, apixaban 50%, rivaroxaban 75%).26 While there is some equipoise in population-based cohorts regarding the clinical implications of these interactions,27-29 in a patient with unexplained recurrent thrombosis, I would recommend careful consideration of potential drug-drug interactions.

In cases of thrombocytopenia and recurrent thrombosis on unfractionated heparin (UFH) or LMWH, heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT) should be excluded. In a recent analysis of over 7 million hospitalizations in patients with solid tumor malignancy, HIT was diagnosed in approximately 8% of patients. Among cancer patients, the incidence of thrombosis was 24.7% in patients with HIT compared with 6.8% of patients without HIT.30

Higher doses of UFH or LMWH may be required to achieve therapeutic anti-Xa levels in the setting of antithrombin deficiency, such as following asparaginase therapy.31,32 Administration of antithrombin concentrates can be considered in cases of refractory thrombosis.

There are conditions where DOACs are less effective than other anticoagulants in the management of thrombosis. Antiphospholipid antibody syndrome, for instance, has been reported following checkpoint blockade.33–35 Warfarin has been shown to be superior to DOACs for management of antiphospholipid antibody syndrome.36

Intravascular devices provide a nidus for recurrent thrombus formation. Approximately 7% of patients with central venous catheters receiving anticoagulation develop recurrent thrombosis.37 In cases of progressive thrombosis of central venous catheters despite therapeutic anticoagulation, I generally favor removal of the catheter rather than altering anticoagulant strategies.

Decreased absorption of DOACs can be seen following gastrointestinal resection. Apixaban is absorbed throughout the gastrointestinal tract,38,39 whereas rivaroxaban is largely absorbed in the stomach and can be considered in patients who have undergone small bowel resection.40 The general guidance is to avoid DOACs are used after bariatric surgery; however, if used, confirming therapeutic anti-Xa levels is recommended.41 The ingestion of rivaroxaban with food should also be queried as the absorption of therapeutic doses of rivaroxaban (20 mg) is up to 40% higher when taken with food rather than on an empty stomach.42,43

Approximately 20% of patients with myeloproliferative neoplasms develop recurrent thrombosis.44 The risk of recurrence is lower in patients receiving cytoreductive and/or concurrent antiplatelet therapy,44 although the addition of aspirin to anticoagulant therapy also significantly increases the risk of hemorrhage.45

Strong and moderate CYP3A4 inducers

| Class . | Strong CYP3A4 inducers . | Moderate CYP3A4 inducers . |

|---|---|---|

| Antineoplastic | Enzalutamide Apalutamide Mitotane Ivosidenib | Dabrafenib Lorlatinib Pexidartinib Sotorasib |

| Other | Carbamazepine Phenytoin Rifampin |

| Class . | Strong CYP3A4 inducers . | Moderate CYP3A4 inducers . |

|---|---|---|

| Antineoplastic | Enzalutamide Apalutamide Mitotane Ivosidenib | Dabrafenib Lorlatinib Pexidartinib Sotorasib |

| Other | Carbamazepine Phenytoin Rifampin |

Management of recurrent VTE in cancer

The more straightforward scenarios for management of recurrent VTE in cancer patients are those where subtherapeutic doses of LMWH or DOACs are administered. In those instances, raising to therapeutic dosing of either LMWH (eg, enoxaparin 1 mg/kg twice daily, dalteparin 200 units/kg daily, tinzaparin 175 units/kg daily) or DOACs is recommended. How to manage cases where patients develop recurrent VTE while on therapeutic anticoagulation is less well defined. As outlined in Table 3, the options include (a) no anticoagulant change, (b) switching anticoagulants, (c) increasing anticoagulant intensity, and (d) placement of an inferior vena cava (IVC) filter and continuation of anticoagulation. ASH guidelines suggest increasing the LMWH dose to supratherapeutic dosing or continuing therapeutic dosing (very low certainty in the evidence) and not placing an IVC filter.46

Potential anticoagulant adjustments in the management of recurrent or refractory thrombosis in cancer

| Current anticoagulant . | Modification . | Example regimen . |

|---|---|---|

| Warfarin | Therapeutic LMWH | Enoxaparin 1 mg/kg BID |

| Subtherapeutic LMWH | Therapeutic LMWH | Enoxaparin 1 mg/kg BID |

| Therapeutic LMWH | 120%–125% LMWH for at least 4 weeks or Switch to DOAC or No change (± IVC filter placement) | Enoxaparin 1.2 mg/kg BID Rivaroxaban 15 mg BID × 21 days, then 20 mg daily |

| Subtherapeutic DOAC | Therapeutic DOAC or Therapeutic LMWH or No change (± IVC filter placement) | Rivaroxaban 20 mg daily Apixaban 5 mg BID |

| Therapeutic DOAC | Switch to therapeutic LMWH or 120%–125% LMWH or “Reload” DOAC | Enoxaparin 1-1.2 mg/kg BID Rivaroxaban 15 mg BID × 21 days, then 20 mg daily |

| Current anticoagulant . | Modification . | Example regimen . |

|---|---|---|

| Warfarin | Therapeutic LMWH | Enoxaparin 1 mg/kg BID |

| Subtherapeutic LMWH | Therapeutic LMWH | Enoxaparin 1 mg/kg BID |

| Therapeutic LMWH | 120%–125% LMWH for at least 4 weeks or Switch to DOAC or No change (± IVC filter placement) | Enoxaparin 1.2 mg/kg BID Rivaroxaban 15 mg BID × 21 days, then 20 mg daily |

| Subtherapeutic DOAC | Therapeutic DOAC or Therapeutic LMWH or No change (± IVC filter placement) | Rivaroxaban 20 mg daily Apixaban 5 mg BID |

| Therapeutic DOAC | Switch to therapeutic LMWH or 120%–125% LMWH or “Reload” DOAC | Enoxaparin 1-1.2 mg/kg BID Rivaroxaban 15 mg BID × 21 days, then 20 mg daily |

Dose-continuation and dose-escalation

There is a paucity of published data to guide management in the case of refractory or recurrent thrombosis in cancer patients. Older retrospective cohort studies (pre-DOAC era) evaluated outcomes in patients receiving either LMWH or vitamin K antagonists at time of recurrence:

In a retrospective cohort of consecutive patients with recurrent VTE, individuals on therapeutic LMWH were administered a 20% to 25% increased dose of LMWH for at least 4 weeks. Those receiving warfarin were switched to LMWH while individuals on lower doses of LMWH were escalated to therapeutic dosing. Among the 15 patients on therapeutic LMWH who received dose-escalation, 3 developed recurrent VTE, and there were no major hemorrhages.47

In a follow-up study conducted between 2008 and 2012, an additional 18 patients on therapeutic LMWH were treated with the 120% to 125% LMWH dosing regimen along with 37 patients who were transitioned from subtherapeutic to therapeutic anticoagulation. In the entire cohort, 4 patients (7.3%) developed recurrent VTE, and 3 patients (5.5%) developed major hemorrhage.48

In a registry cohort study of 212 patients with breakthrough VTE, 70% were receiving LMWH and 27% were receiving vitamin K antagonists at the time of recurrent VTE. In 31% of cases, the dose of LMWH was increased. However, increasing anticoagulant intensity did not reduce the incidence of recurrent VTE compared with the 70 patients who continued the previous dose (HR, 1.09, 95% CI 0.45-2.63).49 Two of 20 patients in the supratherapeutic anticoagulation group developed major hemorrhage, which was comparable to the rate observed in the therapeutic anticoagulation cohort.

Based on the available data, it is not possible to conclude whether short-term (≥4 weeks) LMWH dose-escalation (120% to 125% dosing) is superior to alternative approaches in patients developing recurrent VTE. However, bleeding rates with supratherapeutic dosing appear similar to standard therapeutic anticoagulation.47,49 Accordingly, from a practical standpoint of wanting to trial an alternative anticoagulation strategy, LMWH dose-escalation is a reasonable approach in cases of unexplained progressive or recurrent thrombosis.

Switching anticoagulant classes

The switching of LMWH to DOACs and vice versa is commonly considered in cases of recurrent or refractory thrombosis. In phase 3 trials, DOACs have been shown to be superior to LMWH in preventing recurrent VTE.1-3 As such, it is reasonable to consider DOACs as an alternative in the case of LMWH breakthrough thrombosis, although supporting data are lacking. In patients without contraindications, it is my practice to switch from LMWH to DOAC anticoagulants; I typically favor the transition to rivaroxaban, which includes an empiric 3-week dose-escalated regimen (ie, 15 mg twice daily) as a means to approximate the roughly 4-week dose-escalation “cooling off” phase with dose-escalated LMWH.

Justification to switch from DOAC to LMWH is largely empiric with the theoretical advantage of thrombin inhibitory activity in addition to anti-Xa activity. There is preclinical data supporting the efficacy of LWMH over DOACs in inhibiting catheter-induced thrombin generation.50 LMWH is also considered an effective anticoagulant in the management of highly thrombotic antiphospholipid antibody syndrome, whereas DOACs have suboptimal therapeutic efficacy.36 There are other potential benefits of LMWH over DOAC, including parenteral administration (in cases where gastrointestinal absorption is uncertain), lack of drug interactions, and improved dosing flexibility. Additional data may be forthcoming from the REDUCE study, an ongoing prospective study evaluating the relative efficacy of different anticoagulation strategies in the management of refractory cancer-associated thrombosis.

CLINICAL CASE (continued)

The 65-year-old man with metastatic renal cell carcinoma was diagnosed with a femoral vein deep vein thrombosis and placed on therapeutic dosing of enoxaparin. Lower extremity symptoms improved, but staging imaging revealed thrombus involving the inferior vena cava. According to the outlined algorithm (Figure 1), the initial question is whether this represented a new thrombotic event. There was not a contemporaneous CT performed at the time of the ultrasound, so it is not possible to confidently establish whether it was present at the time of the initial diagnosis of deep vein thrombosis. One could consider performing an MRI to more definitively establish the acuity of thrombus. However, based on the location, the question is whether it actually represented a tumor thrombus (Table 1). In discussion with the radiologist, the impression was that it was a tumor thrombus with an apparent component of bland thrombus. To address the oncologist's question regarding switching from enoxaparin to apixaban for refractory thrombosis, no changes to the regimen were recommended considering (a) the lack of evidence of thrombus acuity and (b) equipoise regarding the benefit of anticoagulation to treat a bland thrombus with concomitant tumor thrombus. The patient initially responded to immunotherapy and continued with therapeutic anticoagulation without developing recurrent VTE.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure

Jeffrey I. Zwicker: research funding: Incyte and Quercegen; data safety monitoring boards: Sanofi, CSL Behring; consultancy: Calyx, Bristol Myers Squibb (BMS), Regeneron, royalty: UptoDate.

Off-label drug use

Jeffrey I. Zwicker: Nothing to disclose.