Abstract

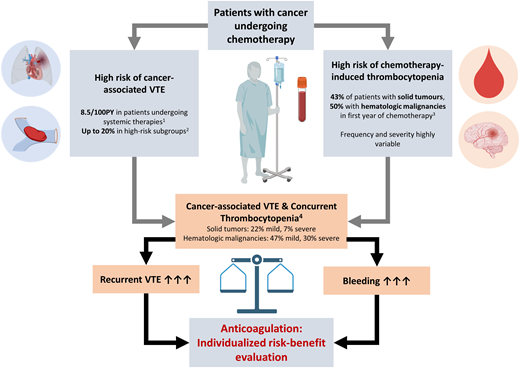

Thrombocytopenia is a frequent complication in patients with cancer, mostly due to the myelosuppressive effects of antineoplastic therapies. The risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE) in patients with cancer is increased despite low platelet counts. The management of cancer-associated VTE in patients with thrombocytopenia is challenging, as the risk of both recurrent VTE and bleeding complications is high. Moreover, the time-dependent nature of thrombocytopenia over the course of antineoplastic therapies further complicates the management of patients in clinical practice. In the absence of evidence from high-quality studies, the management of anticoagulation therapy for VTE must be personalized, balancing the individual risk of VTE progression and recurrence against the risk of hemorrhage. In the present case-based review, we highlight the clinical challenges that arise upon managing cancer-associated VTE in the setting of present or anticipated thrombocytopenia, summarize the available evidence, and provide a comparative overview of available guidelines.

Learning Objectives

Quantify the individual risk of thrombocytopenia associated with commonly used systemic antineoplastic therapies in patients with cancer

Compare the risks of VTE recurrence and bleeding in the management of cancer-associated VTE in the setting of thrombocytopenia

Apply the concept of individualized patient care when managing patients with cancer-associated VTE and concurrent thrombocytopenia

CLINICAL CASE 1

A 43-year-old man with a body weight of 76 kg with relapsed T-cell lymphoblastic lymphoma is initiating chemotherapy according to the Hyper-CVAD protocol (cyclophosphamide, vincristine, adriamycin, dexamethasone). At day 27 after the initiation of chemotherapy, he develops swelling and pain of the left lower limb, raising the suspicion of deep vein thrombosis (DVT). An ultrasound is performed and a femoropopliteal and calf DVT is confirmed. The platelet count of the patient is 34 G/L, the hemoglobin level is 9.2 g/dL, and the white blood cell count is 2.78 G/L. The optimal anticoagulation strategy for treatment of concomitant DVT and severe thrombocytopenia is discussed.

CLINICAL CASE 2

A 62-year-old man with non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), stage IV (bone metastasis), is diagnosed with incidental pulmonary embolism (PE), of multiple segmental and subsegmental pulmonary arteries, in the computer tomography scan performed for restaging after 3 cycles of combined chemoimmunotherapy. He receives oral anticoagulation with apixaban at 5 mg twice daily (after an initial treatment with low-molecular-weight heparin [LMWH] in a therapeutic dose for 2 days and apixaban at 10 mg twice daily for 7 days). Chemoimmunotherapy is continued, and 9 days after the fifth treatment cycle a routine blood count analysis reveals a platelet count of 42 G/L, a hemoglobin level of 10.6 g/dL, a white blood cell count of 1.65 G/L, and an estimated glomerular filtration rate of 39 mL/min. The patient's body weight is 72 kg. How would you proceed with apixaban therapy?

Introduction

Venous thromboembolism (VTE) is a frequent event in patients with cancer and occurs even in those with thrombocytopenia, indicating that a low platelet count is not protective of thrombosis.1-4 Thrombocytopenia again is linked to the type and stage of underlying cancer and cancer treatments and can be observed in the majority of patients with hematological cancers and a relatively high proportion of patients with solid tumors.5,6 While chemotherapy-induced thrombocytopenia represents the most common cause of thrombocytopenia in patients with cancer, alternative causes, including bone marrow infiltration, splenomegaly, disseminated intravascular coagulation, thrombotic microangiopathies, and immune-mediated thrombocytopenia (both cancer or treatment related), should be considered in the diagnostic workup.7

The clinical consequence of low platelet counts is an increased bleeding risk, which renders anticoagulation treatment challenging. Here, we provide an overview on the magnitude of the problem, summarize the available evidence, and review the published guidance statements and recommendations on anticoagulation management in adult patients with cancer-associated VTE and thrombocytopenia. We also discuss anticoagulation strategies for patients with cancer-associated VTE and thrombocytopenia in the changing landscape of anticoagulant therapies with direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs).

Thrombocytopenia and VTE in cancer

Thrombocytopenia is common in patients with cancer, mostly as a consequence of myelosuppressive antineoplastic therapies. In a recent Danish population-based cohort study, thrombocytopenia occurred in 23% of patients with solid tumors within 1 year after cancer diagnosis and in 43% of those initiating chemotherapy.5 The corresponding 1-year risk was 30% in patients with hematologic malignancies and 50% in those initiating chemotherapy.6 The frequency and severity of chemotherapy-induced thrombocytopenia is highly variable, depending on type, duration, dosing, and intervals of applied therapies. An overview of the frequency of thrombocytopenia under selected chemotherapy regimens, which are frequently used, is provided in Table 1 for solid cancers and Table 2 for hematologic malignancies. The duration of chemotherapy-induced thrombocytopenia depends on the platelet lifetime and follows a distinct longitudinal pattern, with the onset of thrombocytopenia around day 6 after cytotoxic therapies, a nadir around day 14, and a gradual return to baseline by day 28-35.8

Risk of thrombocytopenia in selected systemic treatments for solid cancers

| Cancer type . | VTE incidence rate/100 PYa . | Selected systemic therapy . | Thrombocytopenia (any grade)b . | Severe thrombocytopenia (grades 3-4)b . | Reference . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Breast | 1.5/100 PY | Doxorubicin + cyclophosphamide + docetaxel/paclitaxel (adjuvant) | / | <0.5% | Sparano et al, NEJM 2008 |

| Epirubicin + cyclophosphamide followed by docetaxel (neoadjuvant) | / | 1.6% | von Minckwitz G et al, NEJM 2012 | ||

| Paclitaxel (palliative) | / | 0.3% | Miller et al., NEJM 2007 | ||

| Platinum-based neoadjuvant chemotherapy in TNBC | / | 9.6% | Li et al, J Int Med Res 2020 | ||

| CDK4/6 inhibitors | 18.4% | 2.1% | Kassem et al, Breast Cancer 2018 | ||

| Capecitabine | 8.5%-13.9% | 2.4%-2.6% | Nishijima et al, Breast Cancer Res Treat 2016 | ||

| Trastuzumab deruxtecan (advanced Her2-low) | 23.7% | 9.3% | Modi et al, NEJM 2022 | ||

| Trastuzumab deruxtecan vs trastuzumab emtansine (Her2-pos) | 24.9% vs 51.7% | 7.0% vs 24.9% | Cortés et al, NEJM 2022 | ||

| Prostate | 4.2/100 PY | Docetaxel (metastatic; + androgen-deprivation therapy) | / | 0.3% | Sweeney et al, NEJM 2015 |

| Cabazitaxel (mCRPC, pretreated) | 40.8% | 3.2% | De Wit et al, NEJM 2019 | ||

| PARP-inhibitors (mCRPC) | 14.3% | 8.0% | Maiorano et al, Targ Onc 2024 | ||

| NSCLC | 9.5/100 PY | Pemetrexed + platin + pembrolizumab (NSCLC, nonsquamous, palliative) | 18.0% | 7.9% | Gandhi et al, NEJM 2018 |

| Carboplatin + paclitaxel/ nab-paclitaxel + pembrolizumab (NSCLC, squamous, palliative) | 30.6% | 6.8% | Paz-Ares et al, NEJM 2018 | ||

| Cisplatin-based chemotherapy + pembrolizumab (perioperative) | 18.7% | 5.1% | Wakalee et al, NEJM 2023 | ||

| SCLC | 5.9/100 PY | Carboplatin + etoposide + atezolizumab (SCLC, palliative, extensive disease) | 16.2% | 10.1% | Horn et al., NEJM 2018 |

| Colorectal | Colon 7.4/100 PY Rectum 5.8/100 PY | FOLFOX (6 mo, adjuvant, stage III) | / | 1.8% | Grothey et al, NEJM 2018 |

| XELOX (metastatic, pooled from 7 trials) | / | 5.8% | Guo et al, Cancer Invest 2016 | ||

| FOLFOX (metastatic, pooled from 7 trials) | / | 3.2% | Guo et al, Cancer Invest 2016 | ||

| Pancreatic | 17.3/100 PY | FOLFIRINOX (adjuvant) | 47.0% | 1.3% | Conroy et al, NEJM 2018 |

| Gemcitabine (adjuvant) | 50.4% | 5.7% | Conroy et al, NEJM 2018 | ||

| FOLFIRINOX (palliative) | / | 9.1% | Conroy et al, NEJM 2011 | ||

| Gemcitabine + nab- paclitaxel (palliative) | / | 12.8% | Von Hoff et al, NEJM 2013 | ||

| Gastroesophageal | Gastric 8.9/100 PY Esophageal 7.8/100 PY | Triplet chemotherapy (ECF, ECX, EOF, EOX; palliative) | 13.4%-21.1% | 4.3%-5.2% | Cunningham et al, NEJM 2008 |

| Renal cell | 8.9/100 PY | Pembrolizumab + axitinib | 2.6% | 0% | Rini et al, NEJM 2019 |

| Sunitinib | 18%-23.3% | 5%-5.9% | Rini et al, NEJM 2019 | ||

| Nivolumab + ipililumab | <1% | 0% | Motzer et al, NEJM 2018 | ||

| Biliary tract | 12.9/100 PY | Cisplatin + gemcitabine + durvalumab (palliative) | 12.7% | 4.7% | Oh et al, NEJM Evidence 2022 |

| Ovarian | 7.7/100 PY | Paclitaxel + Carboplatin /+ bevacizumab (palliative, stage III, IV) | 9%-12% | 2%-3% | Perren et al, NEJM 2011 |

| Brain | 8.2/100 PY | Temozolomide (newly diagnosed, + radiotherapy) | / | 12% | Stupp et al, NEJM 2005 |

| Sarcoma | NR | Doxorubicin (metastatic soft-tissue sarcoma) | / | <1% | Judson et al, Lancet Onc 2014 |

| Doxorubicin + ifosfamide (metastatic soft-tissue sarcoma) | / | 33% | Judson et al, Lancet Onc 2014 | ||

| Bladder | 9.8/100 PY | Enfortumab vedotin + pembrolizumab vs platin-based chemotherapy | 3.4% vs 34.2% | 0.5% vs 19.4% | Powles et al, NEJM 2024 |

| Cancer type . | VTE incidence rate/100 PYa . | Selected systemic therapy . | Thrombocytopenia (any grade)b . | Severe thrombocytopenia (grades 3-4)b . | Reference . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Breast | 1.5/100 PY | Doxorubicin + cyclophosphamide + docetaxel/paclitaxel (adjuvant) | / | <0.5% | Sparano et al, NEJM 2008 |

| Epirubicin + cyclophosphamide followed by docetaxel (neoadjuvant) | / | 1.6% | von Minckwitz G et al, NEJM 2012 | ||

| Paclitaxel (palliative) | / | 0.3% | Miller et al., NEJM 2007 | ||

| Platinum-based neoadjuvant chemotherapy in TNBC | / | 9.6% | Li et al, J Int Med Res 2020 | ||

| CDK4/6 inhibitors | 18.4% | 2.1% | Kassem et al, Breast Cancer 2018 | ||

| Capecitabine | 8.5%-13.9% | 2.4%-2.6% | Nishijima et al, Breast Cancer Res Treat 2016 | ||

| Trastuzumab deruxtecan (advanced Her2-low) | 23.7% | 9.3% | Modi et al, NEJM 2022 | ||

| Trastuzumab deruxtecan vs trastuzumab emtansine (Her2-pos) | 24.9% vs 51.7% | 7.0% vs 24.9% | Cortés et al, NEJM 2022 | ||

| Prostate | 4.2/100 PY | Docetaxel (metastatic; + androgen-deprivation therapy) | / | 0.3% | Sweeney et al, NEJM 2015 |

| Cabazitaxel (mCRPC, pretreated) | 40.8% | 3.2% | De Wit et al, NEJM 2019 | ||

| PARP-inhibitors (mCRPC) | 14.3% | 8.0% | Maiorano et al, Targ Onc 2024 | ||

| NSCLC | 9.5/100 PY | Pemetrexed + platin + pembrolizumab (NSCLC, nonsquamous, palliative) | 18.0% | 7.9% | Gandhi et al, NEJM 2018 |

| Carboplatin + paclitaxel/ nab-paclitaxel + pembrolizumab (NSCLC, squamous, palliative) | 30.6% | 6.8% | Paz-Ares et al, NEJM 2018 | ||

| Cisplatin-based chemotherapy + pembrolizumab (perioperative) | 18.7% | 5.1% | Wakalee et al, NEJM 2023 | ||

| SCLC | 5.9/100 PY | Carboplatin + etoposide + atezolizumab (SCLC, palliative, extensive disease) | 16.2% | 10.1% | Horn et al., NEJM 2018 |

| Colorectal | Colon 7.4/100 PY Rectum 5.8/100 PY | FOLFOX (6 mo, adjuvant, stage III) | / | 1.8% | Grothey et al, NEJM 2018 |

| XELOX (metastatic, pooled from 7 trials) | / | 5.8% | Guo et al, Cancer Invest 2016 | ||

| FOLFOX (metastatic, pooled from 7 trials) | / | 3.2% | Guo et al, Cancer Invest 2016 | ||

| Pancreatic | 17.3/100 PY | FOLFIRINOX (adjuvant) | 47.0% | 1.3% | Conroy et al, NEJM 2018 |

| Gemcitabine (adjuvant) | 50.4% | 5.7% | Conroy et al, NEJM 2018 | ||

| FOLFIRINOX (palliative) | / | 9.1% | Conroy et al, NEJM 2011 | ||

| Gemcitabine + nab- paclitaxel (palliative) | / | 12.8% | Von Hoff et al, NEJM 2013 | ||

| Gastroesophageal | Gastric 8.9/100 PY Esophageal 7.8/100 PY | Triplet chemotherapy (ECF, ECX, EOF, EOX; palliative) | 13.4%-21.1% | 4.3%-5.2% | Cunningham et al, NEJM 2008 |

| Renal cell | 8.9/100 PY | Pembrolizumab + axitinib | 2.6% | 0% | Rini et al, NEJM 2019 |

| Sunitinib | 18%-23.3% | 5%-5.9% | Rini et al, NEJM 2019 | ||

| Nivolumab + ipililumab | <1% | 0% | Motzer et al, NEJM 2018 | ||

| Biliary tract | 12.9/100 PY | Cisplatin + gemcitabine + durvalumab (palliative) | 12.7% | 4.7% | Oh et al, NEJM Evidence 2022 |

| Ovarian | 7.7/100 PY | Paclitaxel + Carboplatin /+ bevacizumab (palliative, stage III, IV) | 9%-12% | 2%-3% | Perren et al, NEJM 2011 |

| Brain | 8.2/100 PY | Temozolomide (newly diagnosed, + radiotherapy) | / | 12% | Stupp et al, NEJM 2005 |

| Sarcoma | NR | Doxorubicin (metastatic soft-tissue sarcoma) | / | <1% | Judson et al, Lancet Onc 2014 |

| Doxorubicin + ifosfamide (metastatic soft-tissue sarcoma) | / | 33% | Judson et al, Lancet Onc 2014 | ||

| Bladder | 9.8/100 PY | Enfortumab vedotin + pembrolizumab vs platin-based chemotherapy | 3.4% vs 34.2% | 0.5% vs 19.4% | Powles et al, NEJM 2024 |

Contemporary VTE estimates within 1 year after cancer diagnosis in patients who received chemotherapy or targeted therapy within 4 months following diagnosis.

Thrombocytopenia categorized according to the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events of the National Cancer Institute: grade 1: 75-150 G/L, grade 2: 50-75 G/L, grade 3: 25-50 G/L, grade 4: <25 G/L.

Glioblastoma overall.

Adapted with permission from Mulder et al.12

ECF, epirubicin, cisplatin, 5-flourouracil; ECX, epirubicin, cisplatin, capecitabine; EOF, epirubicin, oxaliplatin, 5-flourouracil; EOX, epirubicin, oxaliplatin, capecitabine; FOLFIRINOX, folinic acid (leucovorin), 5-flourouracil, irinotecan, oxaliplatin; FOLFOX, folinic acid (leucovorin), 5-flourouracil, oxaliplatin; Her2, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2; mCRPC, metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer; NHL, non-Hodgkin's lymphoma; PARP, poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase; PY, patient-years; SCLC, small cell lung cancer; TNBC, triple-negative breast cancer; XELOX, capecitabine, oxaliplatin.

Risk of thrombocytopenia in selected cancer therapies for hematologic malignancies

| Cancer type . | VTE incidence rate per 100 PY . | Selected systemic therapy . | Thrombocytopenia (any grade)** . | Severe thrombocytopenia (grades 3-4)** . | Reference . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NHL | 6.3/100 PY | R-CHOP | / | Every 14 days: 9% Every 21 days: 5% | Cunningham et al, Lancet 2013 |

| CLL | 4-year cumulative incidence: 3.1% | FCR/R-bendamustin | 14.9% | 8.4% | Eichhorst et al, NEJM 2023 |

| venetoclax-rituximab | 7.1% | 3.4% | |||

| venetoclax-obinutuzumab | 17.5% | 14.9% | |||

| venetoclax-obinutuzumab-brutinib | 21.7% | 11.3% | |||

| HL | 5.1/100 PY | ABVD | / | 2% | Viviani et al, NEJM 2011 |

| BEACOPP (stage IIB, III, or IV and high risk) | 8% | ||||

| A+AVD | <5% | 0.15% | Ansell et al, NEJM 2022 | ||

| MM | 6.7/100 PY | D-VRd RvD | 48.4% 34.3% | 29.1% 17.3% | Sonneveld et al, NEJM 2024 |

| ASCT | / | 82.7% | Richardson et al, NEJM 2022 |

| Cancer type . | VTE incidence rate per 100 PY . | Selected systemic therapy . | Thrombocytopenia (any grade)** . | Severe thrombocytopenia (grades 3-4)** . | Reference . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NHL | 6.3/100 PY | R-CHOP | / | Every 14 days: 9% Every 21 days: 5% | Cunningham et al, Lancet 2013 |

| CLL | 4-year cumulative incidence: 3.1% | FCR/R-bendamustin | 14.9% | 8.4% | Eichhorst et al, NEJM 2023 |

| venetoclax-rituximab | 7.1% | 3.4% | |||

| venetoclax-obinutuzumab | 17.5% | 14.9% | |||

| venetoclax-obinutuzumab-brutinib | 21.7% | 11.3% | |||

| HL | 5.1/100 PY | ABVD | / | 2% | Viviani et al, NEJM 2011 |

| BEACOPP (stage IIB, III, or IV and high risk) | 8% | ||||

| A+AVD | <5% | 0.15% | Ansell et al, NEJM 2022 | ||

| MM | 6.7/100 PY | D-VRd RvD | 48.4% 34.3% | 29.1% 17.3% | Sonneveld et al, NEJM 2024 |

| ASCT | / | 82.7% | Richardson et al, NEJM 2022 |

Contemporary VTE estimates within 1 year after cancer diagnosis based on Danish population-level data.

Thrombocytopenia categorized according to the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events of the National Cancer Institute: grade 1: 75-150 G/L, grade 2: 50-75 G/L, grade 3: 25-50 G/L, grade 4: < 25 G/L.

ABVD, regimen consisting of doxorubicin, bleomycin, vinblastine and dacarbazine; ASCT, autologous stem cell transplantation; BEACOPP, regimen consisting of bleomycin, etoposide, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, procarbazine and prednisone; CLL, chronic lymphocytic leukemia; D-VRd, Daratumumab, Bortezomib, Lenalidomide, Dexamethasone; FCR, regimen consisting of fludarabine, cyclophosphamide and rituximab; HL, Hodgkin's lymphoma; MM, multiple myeloma; NHL, non-Hodgkin's lymphoma; PY, patient-years; R-CHOP, regimen consisting of cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, prednisone, rituximab and vincristine; VRd, Bortezomib, Lenalidomide, Dexamethasone.

The risk of bleeding in patients with thrombocytopenia increases with lower platelet counts, with a high risk of spontaneous hemorrhage below a threshold of 10 G/L.9 However, the risk of bleeding in the setting of thrombocytopenia is strongly influenced by additional predisposing factors, including disbalance of coagulation, renal or liver dysfunction, higher age, local disruption of mucosal integrity, invasion of vascular structures by cancers, or the presence of intracerebral metastasis.10,11 Therefore, platelet counts alone insufficiently predict the individual risk of bleeding in patients with cancer.

Concurrently, patients with cancer have an increased risk of VTE, which is especially pronounced in those with advanced cancers undergoing systemic therapies.12,13 Therefore, populations at risk of chemotherapy-induced thrombocytopenia often overlap with populations at high risk for cancer-associated VTE, which leads to a relatively high coprevalence of both conditions, complicating anticoagulation management. The prevalence of thrombocytopenia in the setting of acute cancer-associated VTE was investigated in a recent retrospective cohort study. In patients with solid cancers, at VTE diagnosis, 22% of patients had platelet counts lower than 100 G/L, and 7% had counts lower than 50 G/L, compared to 47% and 30% in those with hematologic malignancies, respectively.14 However, platelet counts are a dynamic parameter, and the recurrent and time-dependent course of chemotherapy-induced thrombocytopenia further affects the management of VTE in cancer patients. Therefore, evaluation of anticoagulation therapy for VTE in cancer patients should incorporate an individual assessment of risk of thrombocytopenia and accompanied bleeding risk factors.

Anticoagulation for cancer-associated VTE

Patients with cancer-associated VTE have a high risk of VTE recurrence, especially in the early phase after diagnosis, necessitating therapeutic anticoagulation for 6 months or longer if the cancer is still active or anticancer treatment is ongoing.15-20 DOACs, in particular direct factor Xa inhibitors, have been established for the treatment of cancer-associated VTE as an alternative to LMWH based on randomized controlled trials (RCTs).15,19,21 However, management algorithms and inclusion criteria regarding thrombocytopenia applied in these trials differed and are not informative for clinical practice. In these RCTs, anticoagulation treatment was generally discontinued upon severe thrombocytopenia (ie, platelet count <50 G/L), and different dose adjustment schemes were applied for varying degrees of mild thrombocytopenia (Supplementary Table S1).

Outcomes of VTE in patients with cancer and thrombocytopenia

In the absence of specific data from prospective interventional trials, only limited data on the risk of recurrent VTE and bleeding events for severe thrombocytopenia are available from observational studies. Data from 2 retrospective cohort studies suggest an overall risk of recurrent VTE in patients with thrombocytopenia (<50 G/L) of 27%, whereas the risk of major bleeding is 15%.1 Another retrospective study including patients with hematologic malignancies and VTE in the setting of thrombocytopenia (<50 G/L) reported a 2-year risk of major bleeding in 6% and of VTE progression/recurrence in 21% in those with platelet counts less than 50 G/L.22 In a multicenter prospective cohort study, including 105 patients with hematologic malignancies with acute VTE (within 28 days) and thrombocytopenia (<50 G/L), the 28-day risk of VTE progression was 8%; major bleeding occurred in 7% and clinically relevant nonmajor bleeding in 25%.23 In another multicenter retrospective cohort study including 121 patients with active malignancy, acute VTE, and concurrent thrombocytopenia (platelet counts <100 G/L), the 60-day cumulative incidence of major hemorrhage was 12.8% and of recurrent VTE 5.6% with therapeutic anticoagulation.24 In an analysis of the multinational RIETE registry of 166 patients with cancer-associated acute VTE and thrombocytopenia, the 30-day risk of major bleeding in patients with severe thrombocytopenia (<50 G/L) treated with reduced-dose and therapeutic- dose anticoagulation was 3.4% and 2.9%, whereas the 30-day risk of recurrent VTE was 10.3% and 1.4%, respectively. Further, the 30-day risk of fatal PE was higher as opposed to fatal hemorrhage in individuals with platelet counts higher than 100 G/L (1.3% vs 0.4%) and between 50 G/L and 100 G/L (3.1% vs 0.7%), while the risk was comparable in patients with platelet counts of 20 to 50 G/L (2.9% vs 2.2%).25 In a recent meta-analysis of 19 available observational studies, anticoagulation management and outcomes of patients with cancer-associated thrombosis and thrombocytopenia were analyzed (90% hematologic malignancies).2 Rates of recurrent VTE (2.65 out of 100 patient-months) and major bleeding complications (4.45 out of 100 patient-months) in those receiving full-dose anticoagulation were high, with a significant risk of bias in included studies.2 These observational data underline the need to critically balance the individual risks of VTE recurrence and bleeding in the thrombocytopenic patient with cancer-associated VTE.

Anticoagulation in the thrombocytopenic patient: risk-benefit evaluation

In the absence of data from interventional studies, guidance regarding anticoagulation therapy is based on expert consensus, observational data, and extrapolation of data from other study populations. In general, upon managing VTE in the setting of thrombocytopenia, several main issues should be considered, which largely influence the risk of recurrent VTE and bleeding, respectively. These include the type and acuity of the VTE event; the severity, duration, and anticipated time course of thrombocytopenia; and individual concomitant bleeding-risk factors. Despite the limited role of platelet count alone in predicting bleeding risk, existing guidelines commonly stratify anticoagulation management primarily according to the severity of thrombocytopenia (Table 3).26

Existing guideline statements for the management of VTE in patients with thrombocytopenia

| Guidance . | Setting/topic . | Statement . |

|---|---|---|

| ISTH Scientific and Standardization Committee: Hemostasis and Malignancy, 201826 | CAT, nonsevere thrombocytopenia | “Recommend . . . full therapeutic anticoagulation without platelet transfusion to patients with CAT and a platelet count of ≥50 G/L.” |

| Acute CAT (within 30 days) + high risk of thrombus progressiona | “[For] severe thrombocytopenia (<50 G/L) and a higher risk of thrombus progression, we suggest full-dose anticoagulation (LMWH/UFH) with platelet transfusion support to maintain a platelet count of ≥40-50 G/L.” | |

| Acute CAT (within 30 days) + lower risk of thrombus progressiona | For severe thrombocytopenia (<50 G/L) and a lower risk of thrombus progression: a) Platelet count 25-50 G/L: suggest reducing the dose of LMWH to 50% of the therapeutic dose or using a prophylactic dose. b) Platelet count <25 G/L: suggest temporarily discontinuing anticoagulation. c) Recommend resuming full-dose LMWH when the platelet count >50 G/L. | |

| Subacute/chronic CAT (>30 days since the index VTE) | a) Platelet count 25-50 G/L: suggest reducing the dose of LMWH to 50% of the therapeutic dose or using a prophylactic dose. b) Platelet count <25 G/L: suggest temporarily discontinuing anticoagulation. c) Recommend resuming full-dose LMWH when the platelet count >50 G/L. | |

| American Society of Hematology 2021 guidelines | No specific statement regarding management of CAT in the setting of thrombocytopenia | |

| International Initiative on Thrombosis and Cancer guidelines 2019 and 202218,32 | Cancer-associated VTE (treatment) | “In patients with cancer with thrombocytopenia, full doses of anticoagulant can be used for the treatment of established venous thromboembolism if the platelet count is >50 G/L and there is no evidence of bleeding; for patients with a platelet count below 50 G/L, decisions on treatment and dosage should be made on a case-by-case basis with the utmost caution (guidance, in the absence of data and a balance between desirable and undesirable effects depending on the bleeding risk vs venous thromboembolism risk).” |

| Cancer-associated VTE (prophylaxis) | “In patients with cancer with mild thrombocytopenia with a platelet count >80 G/L, pharmacological prophylaxis can be used; if the platelet count is below 80 G/L, pharmacological prophylaxis can only be considered on a case-by-case basis and careful monitoring is recommended (guidance, in the absence of data and a balance between desirable and undesirable effects depending on the bleeding risk vs venous thromboembolism risk).” | |

| ESMO Clinical Practice Guideline 202315 | Cancer associated VTE, persistent, severe thrombocytopenia (<50 G/L), high risk of thrombus progressionb | “Full-dose anticoagulation may be considered in combination with platelet transfusion support aiming at platelet count >40-50 G/L.” |

| Cancer associated VTE, persistent, severe thrombocytopenia (<50 G/L), low risk of thrombus progressionb | “Intermediate- to prophylactic-dose LMWH may be considered with temporary discontinuation of anticoagulation if the platelet count falls below 25 G/L.” | |

| Cancer-associated VTE, platelet count >50 G/L | “Full therapeutic dose anticoagulation should be considered.” | |

| DOAC use | “Data on the use of DOACs for the treatment of CAT in the presence of severe thrombocytopaenia are lacking.” | |

| ASCO 2023 Guidelines17 | No specific statement regarding management of CAT in the setting of thrombocytopenia | |

| EHA Guidelines 2022.53 | Thrombocytopenia grade 1-2 (platelet count >50 G/L) | “Therapeutic-dose parenteral or oral anticoagulation according to the approved indications after a careful evaluation of bleeding and thrombotic risk in the individual patient” “Thrombocytopenia . . . which is not stable and acute VTE, LMWH should be preferred over DOACs and VKAs.” |

| Thrombocytopenia grade 3 (platelet count 25-50 G/L) | “We recommend against using DOACs and VKAs for VTE.” “LMWH, at doses either prophylactic or therapeutic reduced by 50%, should be used in patients with acute VTE, after balancing bleeding and thrombosis risk.” | |

| Thrombocytopenia grade 3-4 (platelet count <50 G/L) | “In case of very-high-thrombotic risk, we suggest continuing anticoagulation and increase platelet counts by platelet transfusion or use of TPO-RA.” “We recommend resuming the appropriate dose of anticoagulation as soon as platelet count allows.” | |

| UpToDate—anticoagulation in individuals with thrombocytopenia10 | Cancer-associated VTE, platelet count >50 G/L | “Full-dose anticoagulation is generally appropriate, as in nonthrombocytopenic populations. . . . Close monitoring of the platelet count is warranted, especially if the nadir of chemotherapy-induced thrombocytopenia has not yet occurred.” |

| Cancer-associated VTE, platelet count <50 G/L | platelet count 25-50 G/L: without strong bleeding risk factorsc: • higher risk for VTE progression or recurrenced: “full-dose anticoagulation with platelet transfusion support (typically, platelet transfusions to raise the platelet count to ≥50 G/L), especially in the presence of another thromboembolic risk factor.” • lower/intermediate risk for VTE progression or recurrencee or high risk of bleeding: half-dose anticoagulation is the preferred treatment approach for platelet counts between 25-50 G/L; holding anticoagulation is appropriate for platelet counts <25 G/L. other options include prophylactic-dose anticoagulation or temporarily holding anticoagulation.” |

| Guidance . | Setting/topic . | Statement . |

|---|---|---|

| ISTH Scientific and Standardization Committee: Hemostasis and Malignancy, 201826 | CAT, nonsevere thrombocytopenia | “Recommend . . . full therapeutic anticoagulation without platelet transfusion to patients with CAT and a platelet count of ≥50 G/L.” |

| Acute CAT (within 30 days) + high risk of thrombus progressiona | “[For] severe thrombocytopenia (<50 G/L) and a higher risk of thrombus progression, we suggest full-dose anticoagulation (LMWH/UFH) with platelet transfusion support to maintain a platelet count of ≥40-50 G/L.” | |

| Acute CAT (within 30 days) + lower risk of thrombus progressiona | For severe thrombocytopenia (<50 G/L) and a lower risk of thrombus progression: a) Platelet count 25-50 G/L: suggest reducing the dose of LMWH to 50% of the therapeutic dose or using a prophylactic dose. b) Platelet count <25 G/L: suggest temporarily discontinuing anticoagulation. c) Recommend resuming full-dose LMWH when the platelet count >50 G/L. | |

| Subacute/chronic CAT (>30 days since the index VTE) | a) Platelet count 25-50 G/L: suggest reducing the dose of LMWH to 50% of the therapeutic dose or using a prophylactic dose. b) Platelet count <25 G/L: suggest temporarily discontinuing anticoagulation. c) Recommend resuming full-dose LMWH when the platelet count >50 G/L. | |

| American Society of Hematology 2021 guidelines | No specific statement regarding management of CAT in the setting of thrombocytopenia | |

| International Initiative on Thrombosis and Cancer guidelines 2019 and 202218,32 | Cancer-associated VTE (treatment) | “In patients with cancer with thrombocytopenia, full doses of anticoagulant can be used for the treatment of established venous thromboembolism if the platelet count is >50 G/L and there is no evidence of bleeding; for patients with a platelet count below 50 G/L, decisions on treatment and dosage should be made on a case-by-case basis with the utmost caution (guidance, in the absence of data and a balance between desirable and undesirable effects depending on the bleeding risk vs venous thromboembolism risk).” |

| Cancer-associated VTE (prophylaxis) | “In patients with cancer with mild thrombocytopenia with a platelet count >80 G/L, pharmacological prophylaxis can be used; if the platelet count is below 80 G/L, pharmacological prophylaxis can only be considered on a case-by-case basis and careful monitoring is recommended (guidance, in the absence of data and a balance between desirable and undesirable effects depending on the bleeding risk vs venous thromboembolism risk).” | |

| ESMO Clinical Practice Guideline 202315 | Cancer associated VTE, persistent, severe thrombocytopenia (<50 G/L), high risk of thrombus progressionb | “Full-dose anticoagulation may be considered in combination with platelet transfusion support aiming at platelet count >40-50 G/L.” |

| Cancer associated VTE, persistent, severe thrombocytopenia (<50 G/L), low risk of thrombus progressionb | “Intermediate- to prophylactic-dose LMWH may be considered with temporary discontinuation of anticoagulation if the platelet count falls below 25 G/L.” | |

| Cancer-associated VTE, platelet count >50 G/L | “Full therapeutic dose anticoagulation should be considered.” | |

| DOAC use | “Data on the use of DOACs for the treatment of CAT in the presence of severe thrombocytopaenia are lacking.” | |

| ASCO 2023 Guidelines17 | No specific statement regarding management of CAT in the setting of thrombocytopenia | |

| EHA Guidelines 2022.53 | Thrombocytopenia grade 1-2 (platelet count >50 G/L) | “Therapeutic-dose parenteral or oral anticoagulation according to the approved indications after a careful evaluation of bleeding and thrombotic risk in the individual patient” “Thrombocytopenia . . . which is not stable and acute VTE, LMWH should be preferred over DOACs and VKAs.” |

| Thrombocytopenia grade 3 (platelet count 25-50 G/L) | “We recommend against using DOACs and VKAs for VTE.” “LMWH, at doses either prophylactic or therapeutic reduced by 50%, should be used in patients with acute VTE, after balancing bleeding and thrombosis risk.” | |

| Thrombocytopenia grade 3-4 (platelet count <50 G/L) | “In case of very-high-thrombotic risk, we suggest continuing anticoagulation and increase platelet counts by platelet transfusion or use of TPO-RA.” “We recommend resuming the appropriate dose of anticoagulation as soon as platelet count allows.” | |

| UpToDate—anticoagulation in individuals with thrombocytopenia10 | Cancer-associated VTE, platelet count >50 G/L | “Full-dose anticoagulation is generally appropriate, as in nonthrombocytopenic populations. . . . Close monitoring of the platelet count is warranted, especially if the nadir of chemotherapy-induced thrombocytopenia has not yet occurred.” |

| Cancer-associated VTE, platelet count <50 G/L | platelet count 25-50 G/L: without strong bleeding risk factorsc: • higher risk for VTE progression or recurrenced: “full-dose anticoagulation with platelet transfusion support (typically, platelet transfusions to raise the platelet count to ≥50 G/L), especially in the presence of another thromboembolic risk factor.” • lower/intermediate risk for VTE progression or recurrencee or high risk of bleeding: half-dose anticoagulation is the preferred treatment approach for platelet counts between 25-50 G/L; holding anticoagulation is appropriate for platelet counts <25 G/L. other options include prophylactic-dose anticoagulation or temporarily holding anticoagulation.” |

Listed high-risk features: segmental or more proximal PE, proximal DVT, history of recurrent VTE. Listed lower-risk features: distal DVT, incidental subsegmental PE, CRT.

Listed high-risk features: first 30 days from thromboembolic event, segmental or more proximal PE, proximal DVT or a history of recurrent thrombosis. Listed low-risk features: more than 30 days from thromboembolic event, distal DVT, isolated subsegmental PE.

Listed bleeding risk factors: age over 75 years, recent severe bleeding, hematopoietic SCT, coagulation or platelet function abnormality, kidney/liver failure, increased risk for falls.

Listed factors for higher risk: VTE within 30 days, proximal DVT, segmental or more proximal PE. Listed factors for lower risk: isolated distal DVT, isolated subsegmental PE, central-line–associated DVT, or a subacute presentation (ie, >30 days since the acute VTE).

ASCO, American Society of Clinical Oncology; CAT, cancer-associated thrombosis; EHA, European Hematology Association; ESMO, European Society for Medical Oncology; ISTH, International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis; TPO-RA, thrombopoietin receptor agonists; UFH, unfractionated heparin; VKA, vitamin K antagonist.

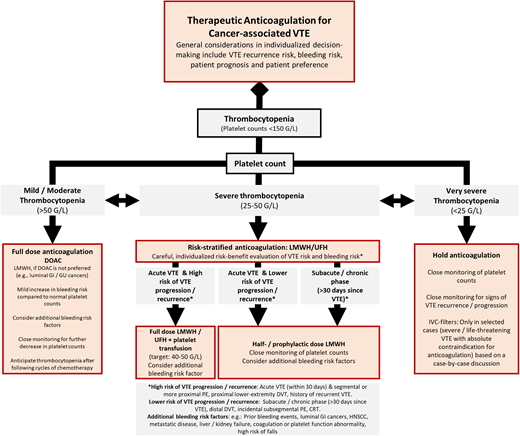

Mild thrombocytopenia (platelet count >50 G/L)

In patients with cancer-associated VTE and mild thrombocytopenia, therapeutic-dose anticoagulation is generally considered safe, with the type and dosing of anticoagulation recommended in accordance with patients without thrombocytopenia.10,15,18,26 However, caution regarding bleeding risk should still be exercised, as in a recent health care–database analysis a mildly increased risk of bleeding in patients with platelet counts between 50 and 100 G/L compared to higher than 100 G/L for DOACs and LMWH was reported.27 Therefore, therapeutic decision-making should include the individual assessment of coexisting bleeding-risk factors, which might be exacerbated by mild thrombocytopenia. In recent pivotal phase 3 trials, the management of anticoagulation for platelet counts of 50 to 100 G/L differed, with no reduction in the dosing of edoxaban in the Hokusai VTE cancer trial and apixaban in the Caravaggio trial, whereas the dose of rivaroxaban was reduced in the Select-D trial (Supplementary Table S1).28-30 For patients receiving LMWH, similar moderate dose-reduction schemes for dalteparin were applied for mild thrombocytopenia in the Caravaggio, Select-D, Hokusai VTE cancer, and Casta Diva trials.28-31 This management of anticoagulation strategies in pivotal clinical trials differs in part from clinical management in routine practice. Presently available guidance statements from published clinical practice guidelines consistently recommend therapeutic-dose anticoagulation for the management of VTE in patients with platelet counts higher than 50 G/L.10,15,18,26,32 However, individual bleeding-risk factors should be considered, and importantly, platelet counts should be closely monitored if the platelet nadir has not yet been reached.

Severe thrombocytopenia (platelet count <50 G/L)

Patients with cancer-associated VTE and severe thrombocytopenia represent a highly vulnerable population at considerable risk of both bleeding complications and VTE progression or recurrence. Therefore, a risk-stratified approach considering the competing risks of bleeding and VTE recurrence and progression is generally recommended for anticoagulation therapy in the individual patient. This risk-benefit evaluation includes 4 key aspects: (a) the timing of VTE (acute phase vs subacute/chronic), (b) the clinical risk profile of the index VTE event, (c) the severity of thrombocytopenia, and (d) the presence of additional strong bleeding-risk factors or active bleeding. While there is some clinical experience on how to use heparins, data on the use of DOACs in patients with severe thrombocytopenia are currently not available. In the pivotal phase 3 trials evaluating DOACs in patients with cancer-associated VTE, DOAC use was interrupted until platelet recovery rose above 50 G/L. Therefore, it is generally recommended to use LMWH or unfractionated heparin for anticoagulation in patients with severe thrombocytopenia.

First, when evaluating anticoagulation management, the acuity and severity of the VTE event must be considered. Generally, the risk of VTE recurrence and/or progression is highest in the initial phase (ie, within 30 days after VTE diagnosis) and in patients with a more severe clinical presentation, including symptomatic segmental or more proximal PE and/or proximal lower-extremity DVT. Therefore, for selected patients with acute VTE and such high-risk clinical features, full-dose anticoagulation is suggested with platelet transfusion support to maintain a platelet threshold of 40 to 50 G/L.10,15,18,26,32 However, this recommendation is based on expert opinion as no interventional trials have yet evaluated this approach. A recent cohort study has analyzed its clinical implementation, supporting the feasibility of platelet transfusion support strategies in this specific setting of acute high-risk VTE.33 However, according to our clinical experience, platelet transfusion may not result in a sufficient increase in platelet counts, especially in patients with hematological cancers with a history of repeated transfusions. Therefore, additional considerations incorporating the individual risk of bleeding are instrumental for decision-making.

In patients with severe thrombocytopenia at lower risk for VTE progression/recurrence, including the subacute or chronic setting after VTE diagnosis (ie, >30 days since the index event) or with a less severe clinical presentation, including patients with distal DVT, isolated subsegmental PE, incidental VTE events, or catheter-related thrombosis (CRT), anticoagulation with a half-therapeutic or prophylactic dose is suggested until the platelet count recovers to above 50 G/L. Clinical decision-making again should incorporate potential additional risk factors for bleeding.

Finally, in patients with such low-risk clinical features with platelet counts less than 25 G/L, the temporary discontinuation of anticoagulation therapy is recommended due to significantly increased bleeding risk.

In Figure 1, we provide a simplified treatment algorithm incorporating key considerations in the risk-benefit evaluation of anticoagulation in patients with cancer-associated VTE and thrombocytopenia.

Proposed management algorithm for the treatment of VTE in patients with cancer and thrombocytopenia. GI, gastrointestinal; GU, genitourinary; HNSCC, head and neck squamous cell carcinoma; UFH, unfractionated heparin.

Proposed management algorithm for the treatment of VTE in patients with cancer and thrombocytopenia. GI, gastrointestinal; GU, genitourinary; HNSCC, head and neck squamous cell carcinoma; UFH, unfractionated heparin.

Additional considerations

Risk of bleeding

Management strategies in patients with thrombocytopenia require an individualized assessment of potential additive bleeding-risk factors, including a prior history of bleeding, renal or hepatic dysfunction, coagulation abnormalities, higher age, and risk for falls.10,27,34 Further, certain cancer types (eg, luminal gastrointestinal, genitourinary, and head and neck cancer) and the presence of intracerebral metastasis might affect the risk of anticoagulation-related bleeding in thrombocytopenic patients.11,27,34,35 In the management of anticoagulation, incorporating these factors in clinical decision-making and optimizing potential modifiable risk factors is crucial.

Venous thrombosis at atypical sites

Importantly, current guidance statements provide no or only very limited information on the management of venous thrombosis at atypical sites in patients with thrombocytopenia, including splanchnic vein thrombosis, which represents an important complication in patients with cancer and is frequently complicated by underlying comorbidities, including hepatic cirrhosis.36 Concomitant thrombocytopenia frequently occurs in patients with cancer-associated splanchnic vein thrombosis, as indicated by a registry-based study reporting that 39.5% of patients had platelet counts less than 100 G/L and 12.7% less than 50 G/L at diagnosis.36 Patients had a high 1-year risk of both major bleeding (11%) and recurrent/progressive splanchnic vein thrombosis (16.3%), which was not affected by the presence of thrombocytopenia.36 In the absence of dedicated clinical trials and specific guidance, we suggest that patients with cancer-associated splanchnic vein thrombosis and concurrent severe thrombocytopenia should be managed on a case-by-case basis, preferably with an intermediate or prophylactic dose until the platelet count recovery rises above 50 G/L, in line with recommendations for VTE at typical sites at low or intermediate risk of VTE progression, with close clinical monitoring for signs of SVT progression/recurrence, as suggested previously.37,38

Further, CRT represents an important subgroup of cancer-associated VTE, and no specific data exist regarding management in the setting of thrombocytopenia. Overall, the risk of VTE recurrence seems to be low, as indicated by a systematic review reporting a pooled 3-month risk of 0.6% from 14 studies evaluating 1128 patients with cancer-associated CRT.39 Importantly, thrombocytopenia represents a common cocomplication in CRT, as central venous catheters are routinely used for intense-regimen chemotherapy in patients with leukemia.40 Based on available guidance, reduced-dose anticoagulation is suggested for patients with CRT and platelet counts less than 50 G/L and temporary discontinuation at less than 25 G/L, according to the suggested approach in VTE events at low or intermediate risk of VTE recurrence and/or progression.26

Prognosis and performance status

Additional considerations that might affect anticoagulation management in patients with cancer-associated VTE and thrombocytopenia include the overall disease prognosis of the patient (ie, very poor short-term prognosis) and decreased performance status. An observational study from multiple palliative and hospice centers indicated a very high burden of VTE in this population, which did not seem to affect patient outcomes.41 Therefore, in an advanced disease setting, risk-benefit evaluations regarding anticoagulation therapy should also incorporate the underlying overall prognosis of a patient.

Acute anticoagulation-related bleeding

Management of acute anticoagulation-related bleeding in the setting of thrombocytopenia should be based on individualized clinical-decision making, incorporating the severity of the bleeding, platelet count, type of anticoagulation, and type and timing of the index VTE event, according to available guidance.42,43 In general, platelet transfusion to maintain platelet counts above 50 G/L in the event of active significant hemorrhage is recommended, with management strategies varying according to type and severity of the bleeding event.43-45 Resuming anticoagulation after an episode of severe bleeding remains an area of uncertainty. Available data from the noncancer population suggest the resumption of anticoagulation as the preferred management strategy based on respective indications for anticoagulation, with varying time intervals depending on the type of bleeding event.46 Further, dose-reduction strategies for future anticoagulation might help reduce the risk of bleeding in these patients yet needs to be carefully balanced against the underlying thrombotic risk.

Prolonged severe thrombocytopenia

Some patient populations typically present with severe, prolonged thrombocytopenia that highly affects anticoagulation management, including patients with acute leukemia and/or patients undergoing hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT). Available data suggest a higher risk of bleeding complications as opposed to VTE in these patients. In a large retrospective cohort study (n = 1514) evaluating patients over 6 months post HSCT, 4.5% had a VTE, whereas clinically significant bleeding occurred in 15.2% and fatal bleeding in 3.6%, with anticoagulation during the observation period associated with a 3-fold increased bleeding risk.47 Further, another retrospective cohort study reported a high burden of bleeding complications compared to a relatively low risk of VTE recurrence during chemotherapy-induced thrombocytopenia prior to platelet engraftment.48 Resuming anticoagulation after engraftment was associated with a reduced risk of recurrent VTE.48 Therefore, in patients with VTE and thrombocytopenia after HSCT, dose-modified anticoagulation strategies are primarily suggested.10 Further, resuming adequate anticoagulation (reduced dose, 25-50 G/L; therapeutic dose, >50 G/L) after platelet reconstitution is suggested.10

Inferior vena cava filters

Inferior vena cava (IVC) filters might be considered on a case-by-case basis in patients with acute VTE with a high risk of clot progression or recurrent PE and absolute contraindications for anticoagulation, including those with active bleeding or persistent, severe thrombocytopenia.26 However, in a population-based observation study IVC filters were not associated with a lower risk of subsequent PE or mortality in patients with cancer-associated VTE.49 In addition, the implantation of IVC filters is characterized by a high rate of clinical complications and adverse events, including dislocation, DVT, and local bleeding.50 Therefore, this approach should only be considered in selected high-risk patients for a limited duration until therapeutic anticoagulation is feasible.

CLINICAL CASE 1 (continued)

Therapy with reduced-dose LMWH (enoxaparin, 8000 IU once daily [1 mg/kg/d], corresponding to intermediate-dose range) was initiated, based on an individualized risk-benefit evaluation of risk of VTE progression and bleeding. The platelet count increased above 50 G/L after 4 days, and the dose of enoxaparin was increased to 8000 IU twice daily, corresponding to a full therapeutic dose. On the following day, the platelet count was 77 G/L, and the patient was discharged home. The decision was made to switch anticoagulation to a DOAC (edoxaban, 60 mg once daily), which was continued until the next cycle of chemotherapy. Meanwhile, the patient recovered from the DVT, as no further symptoms were present. When the platelet count dropped below 50 G/L after the second cycle of chemotherapy, anticoagulation was again switched from the DOAC (edoxaban) to intermediate-dose LMWH (enoxaparin, 8000 IU once daily) until the platelet count reached 40 G/L and was further reduced to a prophylactic dose (enoxaparin, 4000 IU once daily) until the platelet count reached 25 G/L. As the platelet counts did not drop below 25 G/L, there was no need to stop anticoagulation. With recovery of the platelet count and an increase to levels above 50 G/L, anticoagulation was switched again to a DOAC (edoxaban 60 mg/d).

CLINICAL CASE 2 (continued)

The patient was instructed to stop the DOAC (apixaban), and instead a prophylactic dose of LMWH (enoxaparin, 4000 IU/d) was prescribed until the platelet counts recovered to levels above 50 G/L. After 3 days, the blood counts were rechecked, and the platelets had increased to 73 G/L. Consequently, the patient was switched back to apixaban at 5 mg twice daily.

Conclusion

Anticoagulation management of cancer-associated VTE in the setting of thrombocytopenia represents a complex clinical scenario and is challenging. Clinical decision-making should be based on a careful risk-benefit evaluation, balancing the risk of VTE progression and recurrence without anticoagulation against the risk of bleeding, including individual bleeding-risk factors and platelet count levels. Current clinical guidance is based on only limited observational data and mainly expert opinion, emphasizing the need for dedicated prospective studies specifically targeting the anticoagulation management of VTE in the thrombocytopenic patient with cancer. Increasing efforts are currently being directed to providing data on anticoagulation management in thrombocytopenic patients with cancer and acute VTE. In an ongoing open-label pilot trial (NCT05255003),51 the feasibility of conducting a full-scale RCT in this setting is currently being evaluated. Further, there is a need for studies and data focusing on DOACs, as they are increasingly being used in clinical practice for the treatment of cancer-associated VTE.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure

Florian Moik: travel support: Novartis; honoraria: Servier, Bristol Myers Squibb.

Cihan Ay: honoraria: Bayer, Bristol Myers Squibb/Pfizer, Daiichi Sankyo, Sanofi; advisory board: Bayer, Bristol Myers Squibb/ Pfizer, Daiichi Sankyo, Sanofi.

Off-label drug use

Florian Moik: Nothing to disclose.

Cihan Ay: Nothing to disclose.