Abstract

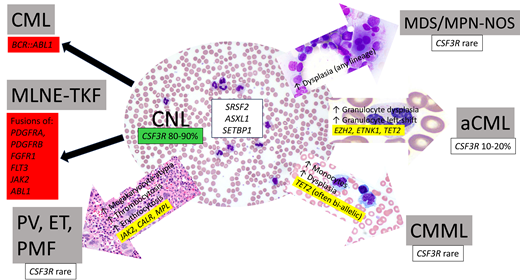

Chronic neutrophilic leukemia (CNL) is a very rare myeloid neoplasm characterized by peripheral blood neutrophilia and a hypercellular marrow with increased granulopoiesis. An activating mutation in CSF3R is present in 80% to 90% of cases. CNL displays some biological overlap in terms of clinical presentation and behavior, as well as genetic profile, with several other myeloid neoplasms, particularly myelodysplastic/myeloproliferative neoplasms (MDS/MPN) and other MPN. Distinguishing these related entities can be challenging, requires close attention to peripheral blood and bone marrow morphology, and can be informed by the mutation pattern: CNL is strongly associated with CSF3R mutation, usually lacks JAK2, MPL, or CALR mutations, and, by definition, lacks BCR::ABL1 rearrangement. Pitfalls in diagnosis include subjectivity in assessing neutrophil dysplasia and distinguishing true neoplastic neutrophilia from reactive neutrophilias that may be superimposed upon or occur as a manifestation of the progression of other myeloid neoplasms. Accurate distinction between neutrophilic myeloid neoplasms is important, as it helps guide patient management and may disclose specific genetic lesions amenable to targeted therapy.

Learning Objectives

Differentiate CNL from related myeloid proliferations using laboratory features, morphology, and genetic testing

Identify mutation patterns associated with CNL and similarities and differences from related myeloid neoplasms

CLINICAL CASE 1

A 70-year-old man presented with chest pain and shortness of breath and was found to have experienced a myocardial infarction. Upon admission he was noted to have leukocytosis (white blood cell count [WBC], 27 × 109/L) with a predominance of neutrophils. His past medical history was significant for coronary artery disease, grand mal seizure disorder, cutaneous melanoma, and spinal stenosis repair. The patient reported that he had had an intermittently elevated WBC (ranging from 17 to 23 × 109/L) for 9 years, without any associated symptoms and or known underlying infection.

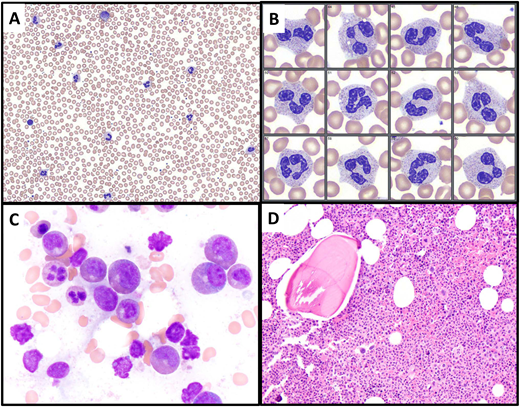

After discharge, the leukocytosis persisted. The patient reported minimal fatigue and was otherwise asymptomatic. He underwent a bone marrow biopsy 7 months after the initial presentation, at which time his complete blood count results were as follows: WBC, 29.6 × 109/L; Hb, 13.5 g/dL; mean corpuscular volume, 95.7 fL; platelet count, 216 × 109/L; WBC differential, 86.2% neutrophils, 8.6% lymphocytes, 3.4% monocytes, 0.3% eosinophils, 0.6% basophils, 0.9% myelocytes. Examination of the peripheral smear revealed increased neutrophils with normal nuclear morphology and normal cytoplasmic granulation (Figure 1A-B). The bone marrow cellularity was 80% (increased for age) and showed an increased myeloid to erythroid ratio with normal maturation and no increase in blasts. Megakaryocytes were normal in number and included a subset of small forms with simplified nuclear contours (Figure 1C-D). Bone marrow flow cytometry showed no abnormalities. The bone marrow karyotype was normal (46, XY [20]). Next-generation sequencing (NGS) on bone marrow showed the following pathogenic mutations: ASXL1 p.G646Wfs*12 (variant allele frequency [VAF], 37.0%), CSF3R p.S810fs* (VAF, 29.7%), SRSF2 p.P95H (VAF, 6.7%), TET2 p.L1081Ffs*23 (VAF, 41.0%).

Illustration of Case 1. (A, B) A peripheral blood smear, showing leukocytosis with neutrophil predominance and only a rare myelocyte (upper center of image A). Neutrophils exhibit normal morphology. (C) The bone marrow aspirate smear shows predominance of granulocytic forms, without significant dysplasia. (D) The bone marrow biopsy is markedly hypercellular with an elevated myeloid to erythroid ratio and intact granulocytic maturation. Megakaryocytes are not increased, do not cluster, and include some small forms.

Illustration of Case 1. (A, B) A peripheral blood smear, showing leukocytosis with neutrophil predominance and only a rare myelocyte (upper center of image A). Neutrophils exhibit normal morphology. (C) The bone marrow aspirate smear shows predominance of granulocytic forms, without significant dysplasia. (D) The bone marrow biopsy is markedly hypercellular with an elevated myeloid to erythroid ratio and intact granulocytic maturation. Megakaryocytes are not increased, do not cluster, and include some small forms.

CLINICAL CASE 2

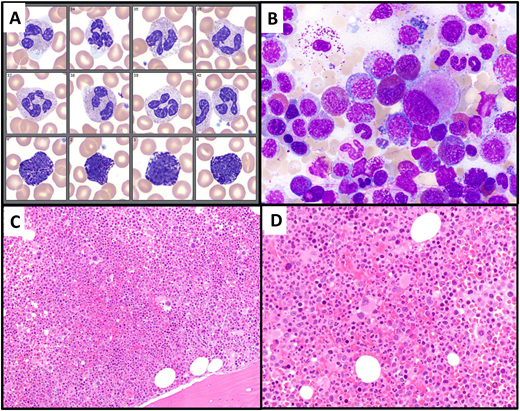

A 57-year-old man presented with nausea and vomiting of 3 weeks' duration and was found to have leukocytosis. His complete blood count results were as follows: WBC, 26.0 × 109/L; hemoglobin (Hb), 16.0 g/dL; mean corpuscular volume, 91.8 fL; platelet count, 193 × 109/L; WBC differential, 68.7% neutrophils, 9.5% lymphocytes, 6.4% monocytes, 6.9% eosinophils, 3.6% basophils, 4.9% immature granulocytes, 0.1 nucleated red blood cells per 100 WBC. Neutrophils in the blood showed normal morphology and basophils were noted to be mildly increased (Figure 2A). His past medical history was significant for hypertension, type 2 diabetes, and substance use disorder. After excluding infectious etiologies, a bone marrow biopsy was performed. The marrow cellularity was 90% (increased for age) and showed a normal myeloid to erythroid ratio with mildly increased eosinophils and no increase in blasts (Figure 2B-D). Bone marrow flow cytometry showed no abnormalities. The bone marrow karyotype was normal (46, XY [cp20]). NGS on bone marrow showed a single pathogenic mutation: ASXL1 p.E635Rfs*15 (VAF, 13.4%). Reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) testing of blood and marrow failed to reveal fusion transcripts associated with p190 or p210 BCR::ABL1 fusion proteins. Anchored multiplex targeted PCR assay revealed a fusion transcript involving ETV6 exon:5 (NM_001987.5) and ABL1 exon:2 (NM_005157.6), confirming ETV6::ABL1 gene fusion.

Illustration of Case 2. (A) A peripheral blood smear (neutrophil and basophil images), showing normal-appearing neutrophils and mild basophilia. (B) Bone marrow aspirate smear shows increased eosinophils (13%) and small hypolobated megakaryocytes. (C, D) Bone marrow biopsy is markedly hypercellular, with a slightly increased myeloid to erythroid ratio and many small hypolobated megakaryocytes.

Illustration of Case 2. (A) A peripheral blood smear (neutrophil and basophil images), showing normal-appearing neutrophils and mild basophilia. (B) Bone marrow aspirate smear shows increased eosinophils (13%) and small hypolobated megakaryocytes. (C, D) Bone marrow biopsy is markedly hypercellular, with a slightly increased myeloid to erythroid ratio and many small hypolobated megakaryocytes.

Chronic neutrophilic leukemia

Chronic neutrophilia (CNL) is a clonal myeloid proliferation characterized by excess neutrophil production resulting in peripheral blood leukocytosis. It is considered to be a type of myeloproliferative neoplasm in the International Consensus Classification (ICC) and World Health Organization fifth edition classification (WHO5) of hematopoietic neoplasms, which codify its diagnostic criteria (Table 1). It is a rare disease (incidence, 0.1/1 000 000 individuals) with a median age at diagnosis of 65 to 70 years.1 Clinically, patients are usually asymptomatic at presentation; the neutrophilia is often detected on routine screening or as part of the workup of another medical condition, as with Case 1. Splenomegaly is present in approximately half of the patients.

| Feature . | Diagnostic requirements . |

|---|---|

| Peripheral blood counts | Total WBC count ≥13/≥ 25 × 109/La Segmented and band neutrophils ≥80% of WBCs Myelocytes, metamyelocytes, and promyelocytes <10% of WBCs Monocytes <10% of WBCs Circulating blasts are rare or absent |

| Morphology | Absence of significant dysgranulopoiesis Hypercellular bone marrow with increased myeloid:erythroid ratio and intact granulocytic maturation |

| Genetics | Activating CSF3R mutationb |

| Exclusions | No BCR::ABL1 rearrangement or rearrangement associated with myeloid/lymphoid neoplasms with eosinophilia and TK gene fusions Not meeting criteria for PV, ET, or PMF |

| Feature . | Diagnostic requirements . |

|---|---|

| Peripheral blood counts | Total WBC count ≥13/≥ 25 × 109/La Segmented and band neutrophils ≥80% of WBCs Myelocytes, metamyelocytes, and promyelocytes <10% of WBCs Monocytes <10% of WBCs Circulating blasts are rare or absent |

| Morphology | Absence of significant dysgranulopoiesis Hypercellular bone marrow with increased myeloid:erythroid ratio and intact granulocytic maturation |

| Genetics | Activating CSF3R mutationb |

| Exclusions | No BCR::ABL1 rearrangement or rearrangement associated with myeloid/lymphoid neoplasms with eosinophilia and TK gene fusions Not meeting criteria for PV, ET, or PMF |

WHO fifth edition classification requires a minimal WBC of 25 × 109/L in all cases, while ICC allows a WBC ≥13 × 109/L in the presence of an activating CSF3R mutation.

In the absence of an activating CSF3R mutation, the neutrophilia must be persistent (≥3 months) and without an identifiable cause, and splenomegaly must be present.

A review of the peripheral blood smear is a critical first step for the diagnosis: CNL lacks myeloid left shift, eosinophilia, basophilia, and dysgranulopoiesis, and these features help set it apart from other myeloid neoplasms in its differential diagnosis. Neutrophils usually appear normal but may show toxic granulation or Döhle bodies. A bone marrow biopsy is an important part of the diagnostic workup since bone marrow hypercellularity due to a marked granulocytic proliferation is part of the required diagnostic criteria for both the ICC and WHO5 (Figure 1). Importantly, bone marrow morphology also helps exclude other myeloid neoplasms that may present with neutrophilia, such as primary myelofibrosis.

A gain-of-function mutation of the CSF3R gene, which encodes the granulocyte colony-stimulating factor receptor, is a hallmark of CNL and was first reported by Maxson and colleagues in 2013.2CSF3R mutations, primarily T618I and T615A point mutations in the membrane proximal region, are present in 80% to 90% of CNL cases overall.3,4 Less common are frameshift mutations (such as that in Case 1) that cause premature truncations of the cytoplasmic tail of the protein. Both types of mutations lead to enhanced or constitutive CSF3R activity, leading to increased downstream JAK-STAT and MAPK signaling, particularly STAT5 activation.5 A diagnosis of CNL can be made in the absence of CSF3R mutation if the neutrophilia is persistent and remains unexplained; in such cases, other evidence of clonality, such as cytogenetic abnormalities and/or somatic gene mutations, are typically present. Similar to Case 1, the majority of CNL cases exhibit additional cooperating mutations, most often involving epigenetic modifier genes (ASXL1, TET2, EZH2, DNMT3A, SETBP1) and spliceosome genes (SRSF2, U2AF1) and less commonly involving signaling genes other than CSF3R (NRAS, PTPN11, CBL, JAK2) (Table 2).6-8 In contrast to the nearly ubiquitous presence of CSF3R and/or other mutations detected by NGS, the karyotype is normal in 63% to 90% of cases. The most common karyotypic abnormalities are +8, +21, del(11q), and del(20q).3,9

Differential diagnosis of CNL (WBC ≥13 × 109/L with neutrophilic predominance)

| Entity . | Neutrophils and bands in blood . | Immature granulocytesa in blood . | Eosinophils . | Basophils . | Monocytes . | Neutrophil morphology . | Megakaryocytes . | Gene fusions . | Mutations . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CNL | ≥80% of WBC | <10% of WBC | <10% of WBC | Usually not increased | <10% of WBC | Normal | Usually normal | None | CSF3R |

| CML | Usually <80% of WBC (except with p230 BCR::ABL1 isoform) | Usually >10% of WBC | Often ≥10% of WBC (especially p190 BCR::ABL1 isoform) | Usually increased | May be ≥10% of WBC | Normal; may be dysplastic in advanced disease | Small and dysplastic- appearing | BCR::ABL1 | No specific |

| MLN-E with TK fusions | Variable | Variable | Usually ≥10% of WBC | May be increased | May be ≥10% of WBC (PDGFRB fusions) | Usually normal | Variable | PDGFRA PDGFRB FGFR1 JAK2 FLT3 ABL1 | No specific |

| aCML | Usually <80% of WBC | ≥10% of WBC | <10% of WBC | Usually not increased | <10% of WBC | Dysplastic | Often small and dysplastic | None | Often SETBP1, ASXL1, or ETNK1 |

| MDS/MPN-NOS | Variable | Variable | <10% of WBC | Variable | <10% of WBC | Often dysplastic | Often small and dysplastic | None | No specific |

| CMML, myeloproliferative | Variable | Variable | Usually <10% of WBC | Usually not increased | ≥10% of WBC | Often dysplastic | Often small and dysplastic | None | Usually SRSF2, ASXL1, or TET2, often in combination |

| Classic MPN with neutrophilia | Variable | Variable | Usually <10% of WBC | May be increased | May be increased | May be dysplastic | Clustered, large, hyperchromatic | None | Usually JAK2, CALR, or MPL |

| MDS with secondary neutrophilia | Variable | Often >10% if due to infection | Usually <10% of WBC | Variable | May be increased | Often dysplastic | Usually small and dysplastic | None | No specific |

| Entity . | Neutrophils and bands in blood . | Immature granulocytesa in blood . | Eosinophils . | Basophils . | Monocytes . | Neutrophil morphology . | Megakaryocytes . | Gene fusions . | Mutations . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CNL | ≥80% of WBC | <10% of WBC | <10% of WBC | Usually not increased | <10% of WBC | Normal | Usually normal | None | CSF3R |

| CML | Usually <80% of WBC (except with p230 BCR::ABL1 isoform) | Usually >10% of WBC | Often ≥10% of WBC (especially p190 BCR::ABL1 isoform) | Usually increased | May be ≥10% of WBC | Normal; may be dysplastic in advanced disease | Small and dysplastic- appearing | BCR::ABL1 | No specific |

| MLN-E with TK fusions | Variable | Variable | Usually ≥10% of WBC | May be increased | May be ≥10% of WBC (PDGFRB fusions) | Usually normal | Variable | PDGFRA PDGFRB FGFR1 JAK2 FLT3 ABL1 | No specific |

| aCML | Usually <80% of WBC | ≥10% of WBC | <10% of WBC | Usually not increased | <10% of WBC | Dysplastic | Often small and dysplastic | None | Often SETBP1, ASXL1, or ETNK1 |

| MDS/MPN-NOS | Variable | Variable | <10% of WBC | Variable | <10% of WBC | Often dysplastic | Often small and dysplastic | None | No specific |

| CMML, myeloproliferative | Variable | Variable | Usually <10% of WBC | Usually not increased | ≥10% of WBC | Often dysplastic | Often small and dysplastic | None | Usually SRSF2, ASXL1, or TET2, often in combination |

| Classic MPN with neutrophilia | Variable | Variable | Usually <10% of WBC | May be increased | May be increased | May be dysplastic | Clustered, large, hyperchromatic | None | Usually JAK2, CALR, or MPL |

| MDS with secondary neutrophilia | Variable | Often >10% if due to infection | Usually <10% of WBC | Variable | May be increased | Often dysplastic | Usually small and dysplastic | None | No specific |

Myelocytes, metamyelocytes, and promyelocytes.

The prognosis of CNL is relatively poor, with a median survival of approximately 24 months.10 Thrombocytopenia, marked leukocytosis (WBC >60 × 109/L), and ASXL1 mutation confer adverse risk in CNL.11 Therapies usually involve cytoreductive agents such as hydroxyurea, while allogeneic stem cell transplant is the only curative therapy. JAK2 inhibitors such as ruxolitinib can be effective, with responses seen in over 50% of CNL patients.12

Differential diagnosis of chronic neutrophilic leukemia

Nonneoplastic neutrophilias

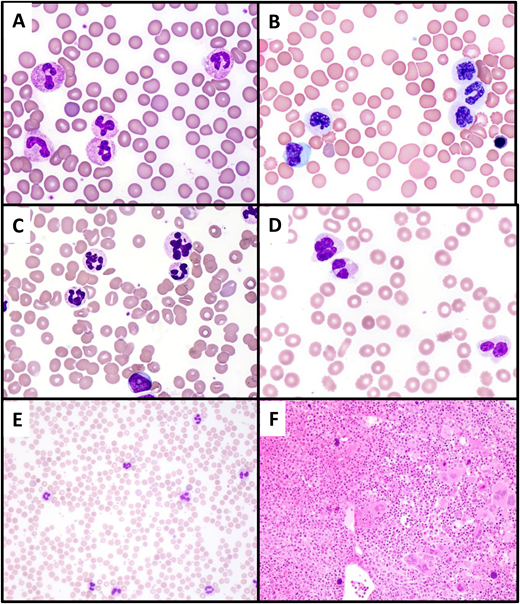

Neutrophilia is much more likely to be reactive in etiology (leukemoid reaction) rather than due to CNL. Infections, systemic inflammatory processes, medications, asplenia, or paraneoplastic phenomena should be excluded clinically prior to embarking on a costly and invasive workup to evaluate for a myeloid neoplasm such as CNL. In particular, bacterial infections such as Clostridium difficile colitis or an occult abscess can produce a significant leukemoid reaction. Regarding paraneoplastic etiologies, plasma cell neoplasms (both overt multiple myeloma and monoclonal gammopathies of undetermined significance) have been associated with neutrophilia mimicking CNL (Figure 3A). Recent data suggest that the majority of granulocytic proliferations in the setting of plasma cell neoplasms are likely reactive in nature, as they usually lack CSF3R and have favorable outcomes.13 Rarer etiologies for neutrophilia include inherited conditions such as cryopyrin-associated periodic syndrome, leukocyte adhesion deficiency, and hereditary neutrophilia.14 Rare cases of hereditary neutrophilia are associated with germline-activating CSF3R mutations,15 while acquired somatic CSF3R mutations commonly occur in the setting of severe congenital neutropenia and may herald leukemic transformation in this setting.16,17

Differential diagnosis of CNL. (A) Paraneoplastic neutrophilia associated with plasma cell myeloma. A 65-year-old man with recurrent plasma cell myeloma presented with marked leukocytosis (WBC, 55 × 109/L; 88% neutrophils). The peripheral blood smear shows normal neutrophil morphology, and NGS studies showed no pathogenic mutations. (B, C) Atypical chronic myeloid leukemia. A 74-year-old man presented with leukocytosis (WBC, 60 × 109/L; 73% neutrophils, 5% metamyelocytes, 5% metamyelocytes, 2% blasts). The peripheral smear shows striking dysgranulopoiesis, with nuclear hyposegmentation and nonlobation (B) or hypersegmentation (C), as well as hypogranulation of neutrophils. A circulating blast is present (lower center of image C). (D) MDS with mutated TP53/MDS with biallelic TP53 inactivation presenting with neutrophilia due to concurrent infection. A 70-year-old man presented with anemia (Hb, 8.5 g/dL) and leukocytosis (WBC, 25.4 × 109/L; 82% neutrophils). The peripheral smear shows markedly dysplastic neutrophils, with nuclear hyposegmentation and hypogranulation. The patient was found to have cellulitis; following treatment of the infection, the WBC normalized to 4.08 × 109/L. (E, F) Primary myelofibrosis (prefibrotic) with neutrophilia. A 49-year-old woman presented with leukocytosis (WBC, 39.6 × 109/L; 85% neutrophils) and thrombocytosis (platelet count, 1256 × 109/L). The peripheral blood smear (E) shows normally granulated neutrophils, without left shift, potentially simulating CNL. The bone marrow biopsy (F) is markedly hypercellular with a granulocytic predominance, also simulating CNL. However, the megakaryocytes are enlarged and hyperchromatic and exhibit prominent clustering, features that suggest a “classic” MPN rather than CNL. NGS showed a JAK2 V617F mutation and the absence of CSF3R mutation.

Differential diagnosis of CNL. (A) Paraneoplastic neutrophilia associated with plasma cell myeloma. A 65-year-old man with recurrent plasma cell myeloma presented with marked leukocytosis (WBC, 55 × 109/L; 88% neutrophils). The peripheral blood smear shows normal neutrophil morphology, and NGS studies showed no pathogenic mutations. (B, C) Atypical chronic myeloid leukemia. A 74-year-old man presented with leukocytosis (WBC, 60 × 109/L; 73% neutrophils, 5% metamyelocytes, 5% metamyelocytes, 2% blasts). The peripheral smear shows striking dysgranulopoiesis, with nuclear hyposegmentation and nonlobation (B) or hypersegmentation (C), as well as hypogranulation of neutrophils. A circulating blast is present (lower center of image C). (D) MDS with mutated TP53/MDS with biallelic TP53 inactivation presenting with neutrophilia due to concurrent infection. A 70-year-old man presented with anemia (Hb, 8.5 g/dL) and leukocytosis (WBC, 25.4 × 109/L; 82% neutrophils). The peripheral smear shows markedly dysplastic neutrophils, with nuclear hyposegmentation and hypogranulation. The patient was found to have cellulitis; following treatment of the infection, the WBC normalized to 4.08 × 109/L. (E, F) Primary myelofibrosis (prefibrotic) with neutrophilia. A 49-year-old woman presented with leukocytosis (WBC, 39.6 × 109/L; 85% neutrophils) and thrombocytosis (platelet count, 1256 × 109/L). The peripheral blood smear (E) shows normally granulated neutrophils, without left shift, potentially simulating CNL. The bone marrow biopsy (F) is markedly hypercellular with a granulocytic predominance, also simulating CNL. However, the megakaryocytes are enlarged and hyperchromatic and exhibit prominent clustering, features that suggest a “classic” MPN rather than CNL. NGS showed a JAK2 V617F mutation and the absence of CSF3R mutation.

Chronic myeloid leukemia

A critical aspect of CNL diagnosis is exclusion of its “alter-ego” —namely, chronic myeloid leukemia (CML). A diagnosis of CNL requires the absence of BCR::ABL1 rearrangement, which would mandate a diagnosis of CML in the setting of neutrophilia. It is important to evaluate for all isoforms of the BCR::ABL1 fusion protein. Sensitive quantitative RT-PCR screening tests typically assess for p210 or p190 isoforms but miss the rare p230 BCR::ABL1 isoform (so-called micro-BCR breakpoint). The telltale t(9;22) can usually be detected by karyotype or fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) in such cases if RT-PCR testing gives a false-negative result. The comprehensive exclusion of BCR::ABL1 is particularly critical since CML with the rare p230 BCR::ABL1 isoform often lacks myeloid left-shift in the blood and thus potentially mimics CNL morphologically.18

Atypical CML (myelodysplastic/myeloproliferative neoplasms with neutrophilia)

Once CML is formally excluded, the main myeloid neoplasm in the differential diagnosis with CNL is atypical CML (aCML, termed myelodysplastic/myeloproliferative neoplasm (MDS/MPN) with neutrophilia in the WHO5). aCML shares a leukocytotic presentation and a hypercellular, myeloid-predominant marrow with CNL. It is distinguished from CNL by the presence of left-shifted granulocytic elements (myelocytes, metamyelocytes, and promyelocytes) composing greater than or equal to 10% of WBCs and significant dysgranulopoiesis, manifesting as neutrophil nuclear hyposegmentation or hypersegmentation, and hypogranulation (Figure 3B-C). In practice, however, the determination of “significant” granulocytic dysplasia can be subjective and borderline cases exist. Genetics can be helpful in that aCML usually lacks CSF3R mutation. However, 10% to 20% of cases otherwise fulfilling criteria for aCML have CSF3R mutations, and furthermore, the background mutational landscape of aCML and CNL is similar.9 Given the overall shared genetic profiles and similar clinical presentations and outcomes in CNL and aCML, some authors have advanced the notion that they do not represent truly discrete morphologic entities but rather exist on a continuum and are better regarded as a single entity.9,19 Thus, while granulocytic dysplasia and left shift represent historic morphologic features separating CNL from aCML, these features may not delineate truly distinct biological entities.

Other MDS/MPN

CNL is formally classified as a “pure” MPN, yet its complex mutational profile bears more semblance to MDS/MPN.19 Determining if sufficient dysplasia is present to warrant a diagnosis of MDS/MPN vs a pure MPN can be subjective. While cytopenias are a characteristic feature of MDS/MPN, hemoglobin and platelet counts in CNL are usually decreased and are not significantly different from those of the MDS/MPN.1,9 MDS/MPN not otherwise specified (MDS/MPN-NOS) could be considered in the differential diagnosis of a myeloid neoplasm with neutrophilia and a cytopenia and is merely separated from CNL by the presence of at least 10% dysplasia in any hematopoietic lineage, an arbitrary threshold. In such cases, rather than rigidly applying diagnostic criteria it is prudent to view the whole picture. For example, a case lacking CSF3R mutation and with an isolated 17q cytogenetic abnormality would likely be most appropriately classified as MDS/MPN with isolated del(17q) (a provisional subtype of MDS/MPN-NOS in the ICC),20 while a case with an activating CSF3R mutation and a normal karyotype may be best diagnosed as CNL even if there appears to be some degree of dysplasia. In Case 1, many of the megakaryocytes have hypolobated nuclei that could be construed as dysplastic (Figure 1), yet the overall features of the case strongly support a diagnosis of CNL.

The most common MDS/MPN by far, chronic myelomonocytic leukemia (CMML), is divided into myeloproliferative and myelodysplastic subtypes based on a WBC of greater than or less than 13 × 109/L, respectively. Myeloproliferative CMML is separated from CNL mainly by the presence of monocytes comprising 10% or more of the WBCs. Like the dysplasia threshold discussed above, this arbitrary monocyte threshold may not delineate true biological entities; the bone marrow morphologic appearance of proliferative CMML overlaps significantly with that of CNL. Interestingly, a rare subset of CMML cases with CSF3R T618I mutation has been described that exhibits frequent ASXL1 mutation and short survival (median, 16.8 months) and may be more biologically related to ASXL1-comutated CNL than to other CMML.21,22

MDS with neutrophilia

Leukocytosis (WBC ≥13 × 109/L) is an exclusionary feature for “pure” myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS), and thus normally MDS would never enter into the differential diagnosis of CNL. However, patients with MDS may develop leukocytosis due to an infection or inflammatory process. This phenomenon should be transient and resolve following treatment, but if present at the time of initial diagnosis, it could result in misclassification as an MDS/MPN or CNL. Close attention to any clinical signs of infection and assurance that the neutrophilia is persistent (particularly in the absence of a CSF3R mutation, which is rare in MDS) is critical to ensure accurate classification of such cases. Neutrophilic dysplasia, usually absent in CNL, is also a clue to alternate diagnoses of MDS or MDS/MPN (Figure 3D). Additionally, some patients with MDS may develop secondary neutrophilia later during the course of disease as a type of progression, often heralded by the acquisition of signaling pathway mutations.23 The relatively newly described clonal cytopenic entity VEXAS is characterized by UBA1 mutation in hematopoietic cells, anemia, and autoinflammatory manifestations; although tissue neutrophilic infiltrates may occur as a manifestation of the autoimmune disease (relapsing polychondritis), neutrophilia is uncommon.24,25

“Classic” myeloproliferative neoplasms

The so-called classic MPNs (polycythemia vera [PV], essential thrombocythemia [ET], and primary myelofibrosis [PMF]) are strongly associated with gain-of-function mutations in genes that, like CSF3R, enhance JAK-STAT signaling: JAK2, CALR, or MPL. These gene mutations are generally exclusive with one another and with CSF3R, but rare cases of CNL may bear a JAK2 comutation,8 and conversely, a small subset of classic MPNs may lack a canonical JAK2, CALR, or MPL mutation. MPN, particularly PMF but also PV and ET, can be associated with significant neutrophilia either at the time of initial diagnosis or upon progression. For this differential diagnosis, both morphology and genetics are helpful: the presence of large, hyperchromatic, and clustered megakaryocytes and a JAK2, CALR, or MPL mutation (without CSF3R) would strongly favor a classic MPN (Figure 3E-F), while normal-appearing or hypolobated, nonclustered megakaryocytes and the absence of the canonical classic MPN mutations would favor CNL. In neutrophilic cases where a JAK2, CALR, or MPL mutation is identified on a limited gene panel, more comprehensive NGS panel sequencing may be considered to identify a CSF3R mutation or other mutation patterns that would argue against a diagnosis of classic MPN.26-28

Myeloid/lymphoid neoplasms with eosinophilia and tyrosine kinase fusions

A distinct category of myeloid neoplasms is a group characterized by fusions of a tyrosine kinase (TK) gene (specifically PDGFRA, PDGFRB, FGFR1, JAK2, or FLT3) with various partners, as well as ABL1 fused with a partner other than BCR (typically ETV6). Similar to BCR::ABL1 in CML, these gene fusions appear at the level of a primitive stem cell that has both myeloid and lymphoid differentiation capacity. These neoplasms typically present as chronic myeloid neoplasms with leukocytosis and eosinophilia but may present without eosinophilia or as overt acute myeloid leukemia or acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Case 2 exemplifies a rare such neoplasm associated with ETV6::ABL1 fusion that mimicked CNL with its presentation as incidental leukocytosis without blood eosinophilia; basophilia, slight granulocytic left shift in the blood, and bone marrow eosinophilia were clues against a diagnosis of CNL. An RNA-based fusion assay revealed the cytogenetically cryptic ETV6::ABL1 fusion and confirmed a diagnosis of myeloid/lymphoid neoplasm with eosinophilia (MLNE) and ETV6::ABL1 fusion. This result was clinically significant, as it disclosed a cytogenetically cryptic lesion amenable to targeted therapy with a TK inhibitor. Case 2 illustrates the importance of applying comprehensive genetic testing to assess for gene fusions in myeloid proliferations that lack defining genetics (such as JAK2, MPL, CALR, or CSF3R mutation) by routine NGS and conventional karyotype. Many TK gene fusions are cytogenetically cryptic, requiring RNAseq, an RNA-based fusion assay, or dedicated FISH probes for their detection.29 Given the responsiveness of these neoplasms to specific targeted therapies, it is critical to correctly identify the underlying gene fusions. Recently, the TK inhibitor pemigatinib was approved for the treatment of myeloid/lymphoid neoplasms with FGFR1 rearrangement.30

Practical approach to the diagnosis of CNLs

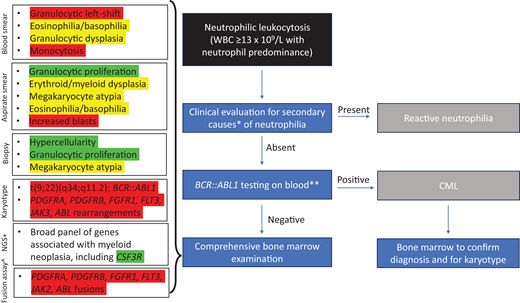

Navigating the differential diagnosis of CNLs requires the integration of clinical features with morphology and, in some instances, detailed genetic evaluation (Table 2). A recommended approach is shown in Figure 4. The first step should be to use the patient's history, laboratory testing, and clinical exam to detect evidence of an underlying infection or other inciting factor and exclude a secondary reactive neutrophilia. Serum protein electrophoresis could be considered to assess for an occult plasma cell neoplasm. If possible, longitudinal blood counts should be examined for chronicity of the neutrophilia. Although flow cytometry is often sent to evaluate leukocytosis, this test is not indicated if the leukocytosis is due to a granulocytic rather than lymphocytic proliferation and should not be part of the routine workup for neutrophilia.

Algorithm for workup of neutrophilic leukocytosis. Red highlights indicate findings that exclude a diagnosis of CNL, yellow highlights indicate findings that are relative contraindications to CNL, and green highlights indicate findings that support a diagnosis of CNL. *Evaluation for signs of infection, underlying neoplasm (including plasma cell neoplasm), drug reaction, or inflammatory condition. **Should include RT-PCR and/or FISH testing that will detect all BCR::ABL1 isoforms +NGS can be performed on blood or bone marrow specimen. ^RNA-seq or NGS-based RNA fusion assay to detect fusions of PDGFRA, PDGFRB, FGFR1, FLT3, JAK2, or ABL1 with various partners; FISH testing for these fusions can also be performed but may miss some fusions.

Algorithm for workup of neutrophilic leukocytosis. Red highlights indicate findings that exclude a diagnosis of CNL, yellow highlights indicate findings that are relative contraindications to CNL, and green highlights indicate findings that support a diagnosis of CNL. *Evaluation for signs of infection, underlying neoplasm (including plasma cell neoplasm), drug reaction, or inflammatory condition. **Should include RT-PCR and/or FISH testing that will detect all BCR::ABL1 isoforms +NGS can be performed on blood or bone marrow specimen. ^RNA-seq or NGS-based RNA fusion assay to detect fusions of PDGFRA, PDGFRB, FGFR1, FLT3, JAK2, or ABL1 with various partners; FISH testing for these fusions can also be performed but may miss some fusions.

If the neutrophilia remains unexplained, particularly if accompanied by basophilia, granulocytic left shift in the blood, or splenomegaly, use RT-PCR and/or peripheral blood FISH to evaluate for a BCR::ABL1 rearrangement, which, if present, would indicate a diagnosis of CML. A broad NGS panel on blood could be considered at this point, but generally a bone marrow examination would be the next step: even if NGS testing reveals pathogenic mutations, there is substantial overlap between the molecular profiles of CNL, aCML, and other MDS/MPN, and a bone marrow biopsy would still be required for definitive classification according to current criteria.

Bone marrow aspirate samples should be sent for conventional karyotype and an NGS panel that includes CSF3R as well as other genes commonly mutated in myeloid neoplasms.29 Additional testing for gene fusions should be considered if the diagnosis is still unclear based on karyotype and NGS results. Regardless of the diagnosis suggested by the blood counts and morphology, a final diagnosis that integrates the molecular and cytogenetic results should always be provided. For example, while the morphology of Case 2 suggested CML or CNL, the final diagnosis after the full genetic results was MLNE with ETV6::ABL1 fusion; communicating this specific diagnosis clearly to the clinical team was critical to ensure appropriate treatment.

Conclusion

CNL is a rare myeloid neoplasm that has a broad differential diagnosis. Although it has a discrete definition that relies on blood count thresholds, morphology, and genetic features, recent studies suggest that CNL may exist on a continuum with other proliferative myeloid neoplasms. Since CNL, aCML, and MDS/MPN-unclassifiable are relatively rare entities, considering them together in a broader group with subcategories defined by genetic clustering and/or gene expression profiles could promote more effective risk stratification, clinical trial accrual, and therapies that target specific genetic aberrations.9,19,31

Conflict-of-interest disclosure

Robert P. Hasserjian: no competing financial interests to declare.

Off-label drug use

Robert P. Hasserjian: None to disclose.