Abstract

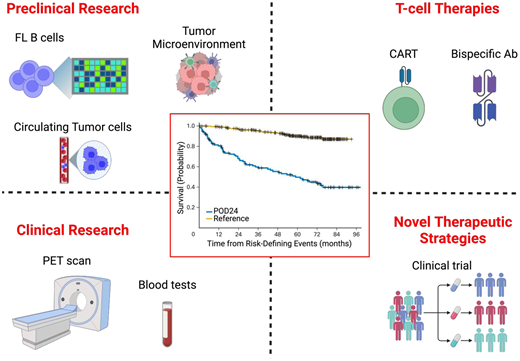

Follicular lymphoma is the most common indolent lymphoma, with a favorable prognosis and survival measured in decades. However, approximately 15% to 20% of patients encounter early disease progression, termed POD24, within 24 months from diagnosis or treatment initiation. Recognizing the correlation between POD24 and a heightened risk of lymphoma-related death has sparked intensive investigations into the clinical and biological determinants of POD24 and the development of innovative treatment strategies targeting this group. Research is also ongoing to understand the varying impact of POD24 based on different clinical contexts and the implications of early histologic transformation on POD24 prognosis. Recent investigations have uncovered potential new predictors of POD24, including genetic and nongenetic alterations as well as some conflicting F-fludeoxyglucose–positron emission tomography characteristics such as maximum standardized uptake value and total metabolic tumor volume. These developments, together with clinical predictors, have led to the emergence of several clinicopathologic tools to help identify at diagnosis patients who may be at higher risk for POD24. As these models are not routinely used, more work is needed to develop new risk-stratification strategies integrating clinical and molecular risk profiling that can be easily implemented in clinical practice to drive therapeutic choice. This review aims to delineate the modest but incremental progress achieved in our understanding of POD24, both clinically and biologically. Furthermore, we offer insights into the best practices to approach POD24 in the current era, aspiring to chart a new path forward to optimize patient outcomes.

Learning Objectives

Review POD24 origins and survival outcomes

Examine currently available biomarkers, molecular insights, and calculators for POD24

Discuss the impact of histologic transformation on survival in POD24

Outline future directions for the management and approach to POD24

CLINICAL CASE

A 58-year-old woman presented with fatigue, back pain, and inguinal lymphadenopathy. A biopsy revealed low-grade follicular lymphoma (FL). Positron emission tomography (PET) imaging revealed advanced- stage disease with a high tumor burden based on an 8.5-cm retroperitoneal nodal conglomerate causing ureteral compression and several other areas of enlarged lymph nodes. The maximum standardized uptake value (SUVmax) was 10. Laboratory tests showed anemia and elevated β2 microglobulin (B2M) and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH). The Follicular Lymphoma International Prognostic Index (FLIPI) score was 4 (high risk). She was treated with bendamustine and rituximab (BR) for 6 cycles and achieved a complete response. Eight months later (14 months from diagnosis), she noticed night sweats, weight loss of 13 lbs, and the reemergence of multiple lymph nodes. Is early disease progression or relapse within 24 months (POD24) still an important risk factor for increased mortality?

POD24 in FL and impact on survival

FL is the most common indolent lymphoma, with a generally favorable outcome. However, approximately 20% of patients treated with rituximab-chemotherapy regimens experience POD24, with an overall survival (OS) of 50% at 5 years,1 compared to those relapsing after this landmark who have a prognosis comparable to the general population without lymphoma.2 POD24 as a prognostic biomarker was originally identified in the National LymphoCare Prospective Observational Study nearly a decade ago, tested mostly in patients treated with rituximab-cyclophosphamide-doxorubicin-vincristine-prednisone (R-CHOP), the most common chemotherapy regimen used at the time. Since that publication the prognostic importance of early recurrence has been validated in several patient registries and multiple retrospective studies using different immunochemotherapy strategies as well as in clinical trial settings (Table 1).2-6 This includes a pooled analysis of over 5000 patients with FL treated in 13 international randomized clinical trials.5 POD24 similarly has a prognostic impact in FL patients treated with nonimmunochemotherapy regimens such as up-front rituximab (R)-based nonchemotherapy doublets (R-galiximab, R-epratuzumab, R-lenalidomide).7 Recent reports demonstrate that the frequency and incidence of POD24 is affected by the type of first-line therapy used and occurs less often (10%-15%) when patients receive bendamustine with obinutuzumab or bendamustine with rituximab.6,8 Additionally, POD24 following first-line bendamustine-based therapies appear to have a much greater risk of histologic transformation (HT), which has the most significant impact on mortality. Unfortunately, though part of guideline-driven management recommendations,9,10 biopsies at the first relapse of FL are infrequently performed in clinical practice in patients lacking clinical symptoms for transformed disease. As a substantial proportion of patients at the time of POD24 may have HT, this represents a missed opportunity to accurately assess transformation incidence and to study biomarkers of disease progression, which could help guide novel therapeutic strategies. Several large data sets (some under active investigation, unpublished data) are exploring differences in the outcomes following POD24 depending on FL vs transformed histology.

POD24 rate and impact on survival

| . | Regimens . | Type of study . | No. of patients . | POD24 . | Survival . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| National LymphoCare Prospective Observational Study1 | R-CHOP | Retrospective | 588 | POD24: 19% (n = 110) No POD24: 71% (n = 420) | 5-y OS: 50% vs 90% |

| Jurinovic et al3 | R-CHOP followed by IFN-α maintenance R-CVP followed by R-maintenance | Clinical trial (GLSG2000 trial; n = 151) and population-based registry (BCCA; n = 107) | 258 | GLSG - POD24: 17% (n = 23) No POD24: 83% (n = 109) BCCA - POD24: 23% (n = 23) No POD24: 77% (n = 79) | GLSG - 5-y OS: 41% vs 91% BCCA - 5-y OS: 26% vs 86% |

| Weillbull et al4 | R-chemo (R-CHOP, n = 308; BR, n = 150, R-CVP, n = 45; R-FC, n = 16), R-mono (n = 273), Others (n = 156) | Population-based registry (Swedish Lymphoma Register) | 948 | R-chemo - POD24: 61% (n = 110) No POD24: 39% (n = 69) R-mono - POD24: 68% (n = 113) No POD24: 32% (n = 52) | R-chemo - 5-y OS: 46% vs 82% R-mono - 5-y OS: 73% vs 85% |

| Casulo et al5 | 10 induction R-chemo and 3 maintenance randomized trials | Clinical trials | 5225 | POD24: 29% (n = 1531) No POD24: 68% (n = 3564) | 3-y OS: 87% vs 98% 5-y OS: 71% vs 93% |

| Seymour et al6 | R- vs O-CHOP/BR | Clinical trial (GALLIUM trial) | 1202 | POD24: 13% (n = 155) No POD24: 76% (n = 916) | 2-y OS: 82% vs 98% |

| CALGB trials7 | R-galiximab, R-epratuzumab, R-lenalidomide | Clinical trials (CALGB 50402, CALGB 50701, CALGB 50803) | 174 | POD24: 28% (n = 48) No POD24: 72% (n = 126) | 2-y OS: 80% vs 99% 5-y OS: 74% vs 90% |

| Freeman et al8 | BR followed by R-maintenance | Population-based registry (BCCA) | 296 | POD24: 13% (n = 37) | 2-y OS: 38% |

| . | Regimens . | Type of study . | No. of patients . | POD24 . | Survival . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| National LymphoCare Prospective Observational Study1 | R-CHOP | Retrospective | 588 | POD24: 19% (n = 110) No POD24: 71% (n = 420) | 5-y OS: 50% vs 90% |

| Jurinovic et al3 | R-CHOP followed by IFN-α maintenance R-CVP followed by R-maintenance | Clinical trial (GLSG2000 trial; n = 151) and population-based registry (BCCA; n = 107) | 258 | GLSG - POD24: 17% (n = 23) No POD24: 83% (n = 109) BCCA - POD24: 23% (n = 23) No POD24: 77% (n = 79) | GLSG - 5-y OS: 41% vs 91% BCCA - 5-y OS: 26% vs 86% |

| Weillbull et al4 | R-chemo (R-CHOP, n = 308; BR, n = 150, R-CVP, n = 45; R-FC, n = 16), R-mono (n = 273), Others (n = 156) | Population-based registry (Swedish Lymphoma Register) | 948 | R-chemo - POD24: 61% (n = 110) No POD24: 39% (n = 69) R-mono - POD24: 68% (n = 113) No POD24: 32% (n = 52) | R-chemo - 5-y OS: 46% vs 82% R-mono - 5-y OS: 73% vs 85% |

| Casulo et al5 | 10 induction R-chemo and 3 maintenance randomized trials | Clinical trials | 5225 | POD24: 29% (n = 1531) No POD24: 68% (n = 3564) | 3-y OS: 87% vs 98% 5-y OS: 71% vs 93% |

| Seymour et al6 | R- vs O-CHOP/BR | Clinical trial (GALLIUM trial) | 1202 | POD24: 13% (n = 155) No POD24: 76% (n = 916) | 2-y OS: 82% vs 98% |

| CALGB trials7 | R-galiximab, R-epratuzumab, R-lenalidomide | Clinical trials (CALGB 50402, CALGB 50701, CALGB 50803) | 174 | POD24: 28% (n = 48) No POD24: 72% (n = 126) | 2-y OS: 80% vs 99% 5-y OS: 74% vs 90% |

| Freeman et al8 | BR followed by R-maintenance | Population-based registry (BCCA) | 296 | POD24: 13% (n = 37) | 2-y OS: 38% |

IFN-α, interferon alfa; O-CHOP, obinutuzumab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone; R-CVP, rituximab-cyclophosphamide- vincristine-prednisone; R-FC, rituximab, fludarabine, and cyclophosphamide; R-mono, rituximab monotherapy.

Active investigation is focused on the study of altered molecular and immune programs responsible for the clinical phenotype of POD24, which may represent targets for more effective therapies for both retained FL histology and transformed disease. Many evolving molecular markers have been implemented into new risk scores to improve the up-front identification of patients likely to experience an aggressive clinical course. Similarly, PET shows promise in predicting the likelihood of developing POD24. Collectively, however, these approaches are seldom used and remain largely investigational.

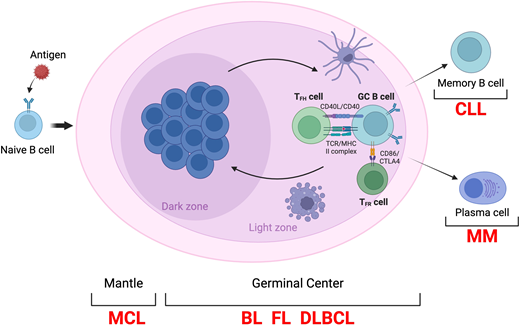

Normal precursor to FL: the germinal center B cell

To improve our knowledge of the pathogenesis of FL, it is critical to have a better understanding of its normal counterpart: the germinal center (GC) B cell. Seminal genetic analyses of FL have unveiled alterations hijacking the functional programs controlling the dynamic of the GC reaction,11,12 a highly specialized structure that forms transiently in the lymphoid tissue after the interaction of naive B cells with a pathogen and from which FL as well as most B cell lymphomas arise (Figure 1).13 Normally, GC B cells recirculate between 2 main compartments: the dark zone (DZ) and light zone (LZ), each representing a location for distinct function. Initially, the hyperproliferative DZ B cells (also called “centroblasts”) undergo somatic hypermutation (SHM) aimed at producing high-affinity antibodies against the foreign antigen.14,15 Subsequently, GC B cells migrate to the LZ as “centrocytes,” where their affinity to the antigen is rechallenged in a competition to engage a limited number of T follicular helper (Tfh) cells.16 Most GC B cells fail to interact with the Tfh cells and undergo apoptosis. The few high-affinity GC B cells can either re-enter the DZ for additional rounds of proliferation and SHM (a MYC-driven process called GC recycling) or exit the GC reaction and terminally differentiate in plasma cells or quiescent long-lived memory B cells.17 In case of a secondary antigen challenge, memory B cells are activated and can differentiate into either long-lived plasma cells or reenter the GC for additional rounds of clonal expansion and SHM.18

Schematic representation of the GC reaction. BL; CLL, chronic lymphocytic leukemia; MCL, mantle cell lymphoma; MHC, major histocompatibility complex; MM, multiple myeloma; TCR, T cell receptor; TFR., T follicular helper cell.

Schematic representation of the GC reaction. BL; CLL, chronic lymphocytic leukemia; MCL, mantle cell lymphoma; MHC, major histocompatibility complex; MM, multiple myeloma; TCR, T cell receptor; TFR., T follicular helper cell.

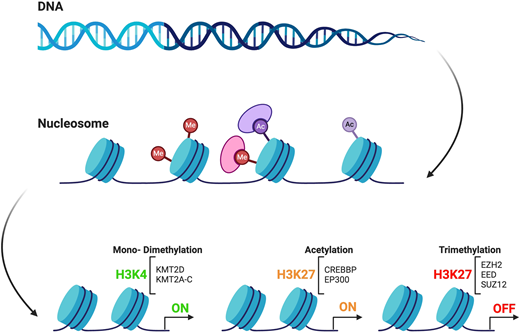

Genetic mutations of chromatin modifier genes and their role in FL pathogenesis

Although the GC is tightly regulated by a complex network of transcription factors and epigenetic modifiers, somatic mutations affecting these regulatory genes can subvert the fine-tuned balance within the GC reaction and allow for proliferative advantage.19 Notably, mutations in chromatin modifier genes (CMGs) are the hallmark of FL, being present in almost 90% of cases.12 The 3 most frequently mutated CMGs in FL are KMT2D (up to 80%), CREBBP (~40%-60%), and EZH2 (25%-30%) (Figure 2).11,12 Mutations in these genes are critical since they provide the backbone to the common precursor cell (CPC) from which overt lymphoma and transformation arise, as discussed later in the review.20,21 It is intriguing that KMT2D, CREBBP, and EZH2 control the same GC B-cell transcriptional programs by targeting the enhancers and promoters, respectively.22-27 As multiple CMG mutations often coexist in FL tumors,28 this would imply the existence of an epigenetic crosstalk that more effectively disrupts the intricate network of mechanisms that regulate and control fundamental cell functions and immune response. However, a complex genetic background is insufficient for tumor development.29 Recently, the tumor microenvironment (TME) has emerged as a critical player in this process since it is able to trigger epigenetic changes that can dampen or promote lymphomagenesis.29,30 Therefore, it is imperative to account for the role of TME in FL etiology. In light of early progression, CMG mutations and altered TME have been investigated as putative drivers of more aggressive biological features like transformed disease or POD24 and may represent potential targets for therapy.

Circuits of epigenetic regulation by representative chromatin modifiers.

Clinical biomarkers of POD24

Multiple clinical factors predicting poor outcomes in FL and the risk of POD24 have consistently been identified across various studies. Established risk models combining these variables, such as the FLIPI, FLIPI2, PRIMA-PI, and FLEX, have been tested to determine their reliability in identifying POD24 but demonstrate varying accuracy and have not entered clinical practice (Table 2).31 Recently, our group developed a novel risk model using 5 continuous variables easily and reliably measured at diagnosis (age, hemoglobin, white blood cell count, LDH, and B2M) (termed FLIPI24). FLIPI24 scores were grouped into 5 risk groups ranging from very low to very high risk for an early event. The FLIPI24 identified poor outcomes among patients with a high/very high-risk score (FLIPI24 > 20%), with a median EFS of 1.8 years (95% CI, 1.3-3.28) and 5-year OS of 65% (95% CI, 55.9-75.8). This blood-based clinical model was superior to the FLIPI for prediction of survival in patients observed (c = 0.706 vs c = 0.596) or treated with rituximab monotherapy (c = 0.726 vs c = 0.721) or immunochemotherapy (c = 0.682 vs c = 0.629) in internal and external validation sets, presenting an opportunity to develop risk stratification for frontline therapy.32,33 Of interest, B2M was the most informative variable in the FLIPI24 model and also seemed to be driving survival differences in the PRIMA-PI. However, validation in independent patient cohorts is required to verify the robustness of FLIPI24 and confirm its prognostic value and clinical utility.

Risk-assessment tools and clinical biomarkers associated with POD24

| . | Components . | Risk groups . | Survival . | POD24 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FLIPI | Age; stage; Hb; LDH; nodal sites | Low: 0-1 Intermediate: 2-3 High: 4-5 | Low: 92% Intermediate: 90% High: 67% | Low/Intermediate: 4%-6% High: 7%-14% |

| FLIPI2 | B2M; diameter lymph node; BMI; age | Low: 0 Intermediate: 1-2 High: 3-5 | Low: 91% Intermediate: 69% High: 51% | |

| PRIMA-PI | B2M; BMI | Low: B2M ≤ 3, no BMI Intermediate: B2M ≤ 3 with BMI High: B2M > 3 | Low: 69% Intermediate: 55% High: 37% | Low: 5% Intermediate: 7% High: 12% |

| FLEX | Male sex; sum of lesion dimension; grade 3A; extranodal sites; ECOG; Hb; B2M; NK cell count; LDH | Low: 0-2 High: 3-9 | Low: 86% High: 68% | Low: 5% High: 8% |

| m7-FLIPI | FLIPI; ECOG; mutation status of 7 genes (ARID1A, CARD11, CREBBP, EP300, EZH2, FOXO1, MEF2B) | Low: <0.8 High: >0.8 | Low: 77% High: 38% | Low: 7% High: 17% |

| POD24-PI | High-risk FLIPI; mutation status of 3 genes (EP300, EZH2, FOXO1) | Low: <0.71 High: >0.71 | Low: 77% High: 50% | Low: 4% High: 14% |

| . | Components . | Risk groups . | Survival . | POD24 . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FLIPI | Age; stage; Hb; LDH; nodal sites | Low: 0-1 Intermediate: 2-3 High: 4-5 | Low: 92% Intermediate: 90% High: 67% | Low/Intermediate: 4%-6% High: 7%-14% |

| FLIPI2 | B2M; diameter lymph node; BMI; age | Low: 0 Intermediate: 1-2 High: 3-5 | Low: 91% Intermediate: 69% High: 51% | |

| PRIMA-PI | B2M; BMI | Low: B2M ≤ 3, no BMI Intermediate: B2M ≤ 3 with BMI High: B2M > 3 | Low: 69% Intermediate: 55% High: 37% | Low: 5% Intermediate: 7% High: 12% |

| FLEX | Male sex; sum of lesion dimension; grade 3A; extranodal sites; ECOG; Hb; B2M; NK cell count; LDH | Low: 0-2 High: 3-9 | Low: 86% High: 68% | Low: 5% High: 8% |

| m7-FLIPI | FLIPI; ECOG; mutation status of 7 genes (ARID1A, CARD11, CREBBP, EP300, EZH2, FOXO1, MEF2B) | Low: <0.8 High: >0.8 | Low: 77% High: 38% | Low: 7% High: 17% |

| POD24-PI | High-risk FLIPI; mutation status of 3 genes (EP300, EZH2, FOXO1) | Low: <0.71 High: >0.71 | Low: 77% High: 50% | Low: 4% High: 14% |

BMI, body mass index; Hb, hemoglobin.

Merging tumor and host factors: clinicomolecular risk models for POD24

Several years ago, the clinicogenetic risk model m7-FLIPI was developed by integrating the mutation of 7 genes (EZH2, ARID1A, MEF2B, EP300, FOXO1, CREBBP, and CARD11)— selected out of a panel of 74 genes—with 2 clinical variables, the FLIPI and Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status in 2 patient cohorts.34 m7-FLIPI dichotomized patients into high- and low-risk groups. Importantly, the m7-FLIPI improved risk stratification in FL by reclassifying high-risk patients by FLIPI into a low-risk m7-FLIPI. However, later investigation found that its prognostic impact was not treatment agnostic. m7-FLIPI lost its prognostic value in patients who received bendamustine-based therapies.34 A subsequent study assessed the utility of m7-FLIPI to identify POD24. The modified classifier, termed POD24-PI, demonstrated that integration of the 3 highest-weighted genetic components of m7-FLIPI (EP300, FOXO1, and EZH2) with high-risk FLIPI led to greater specificity to predict POD24 compared to FLIPI. Among these genes, EZH2 was the sole CMG mutation contributing to a prediction of POD24.3 Huet et al developed a 23-gene expression profiling panel (23-GEP) to discover gene signatures predictive of unfavorable outcomes in FL. The 23-GEP was based on the expression of genes involved in critical B-cell pathways (eg, cell cycle, DNA repair, immune response) that correlated with progression-free survival (PFS) in the PRIMA trial. They found that the panel improved the identification of high-risk patients, and its prognostic value was confirmed in 2 additional independent cohorts.35 Interestingly, tumors with early relapse were enriched for genes highly relevant to the GC biology, namely FOXO1,36PRDM15,37EML6,38SEMA4B.39 However, this model, too, showed a modest ability to predict early relapse, with 38% POD24 in high-risk group vs 19% POD24 in low-risk group. This 23-GEP predicted POD24 with an overall sensitivity of 43% and a specificity of 79%, resulting in 38% positive predictive value and 82% negative predictive value.35

Despite its promise, tumor mutation profiling remains an investigational tool not yet ready for clinical use. m7-FLIPI and GEP-23 are not robust prognostic models and are based on expensive and complex platforms that are difficult to analyze. Additionally, they were performed only on chemotherapy-treated patients, thus limiting their utility for other therapeutic modalities (eg, rituximab monotherapy, observation).40 Future efforts should focus on the development of simpler sequencing techniques able to capture the genetic profile of FL in a cost-effective and timely manner to readily implement stratification and management of patients.

The importance of the FL TME in POD24 pathogenesis and prognosis

As the TME appears to be a key contributor to treatment failure,41 our group developed the bioclinical risk model BioFLIPI, which integrated the expression of intrafollicular CD4 T cells with FLIPI in 2 patient cohorts (Table 3).42 CD4 was selected out of 11 microenvironmental determinants (CD4, CD8, FOXP3, CD32b, CD14, CD68, CD70, SIRPα, TIM3, PD1, PDL1) as a lack of intrafollicular CD4 expression was the only predictor of POD24 that replicated with a pooled OR of 2.37 (95% CI, 1.48-3.79). BioFLIPI moved patients up 1 FLIPI risk group, adding a new fourth high-risk group. The c-statistic for BioFLIPI was 0.665, which was higher compared to FLIPI alone (0.636). BioFLIPI was also strongly predictive of continuous EFS (HR, 1.36; 95% CI, 1.06-1.73; P = .015), OS (HR, 1.47; 95% CI, 0.99-2.17; P = .05), and these associations held after adjusting for FLIPI. Since the microenvironment may be influenced by the genomic composition of the tumor, we investigated whether the BioFLIPI was impacted by the genetic features of the tumor as assessed by the 23-GEP. Notably, the BioFLIPI and high 23-GEP score were each independently predictive of early disease failure.42 Tobin et al investigated the impact of the TME assessed by digital gene expression profiling on POD24 and found that early progression events were enriched for low immune infiltration and low PDL2 expression.43 Additionally, tumors with low immune infiltration showed decreased expression of immune effector and macrophage signatures compared to those with high immune infiltration.43 Single-cell studies have recently attempted to shed light on the complexity of the TME in FL. Haebe et al have identified 13 immune clusters in FL, including T regulatory cells, T follicular helper (Tfh) cells, T effector populations (memory, activated, and exhausted), 2 myeloid, and 3 follicular dendritic cells. Even though the composition of the TME was similar between 2 nodal sites in the same patients, there was heterogeneity in the abundance of Tfh 2s and in their expression of checkpoint.44 A subsequent study found similar T-cell populations but also identified a cluster of CD4 cytotoxic T cells (CD4CTL) not previously described. To recapitulate the heterogenous nature of the TME in FL, Han et al generated TME signatures by using RNA profiling reflecting the composition of cell types within the lymphoma tumor. The signature depleted for T-cell subsets had the worst outcome compared with the others, including naive (high in CD4 naive, CD8 effector, and naive), warm (high in CD8 exhausted [CD8exh], T regulatory cells, and Tfh), and intermediate (high in malignant B cells and depleted in CD4 naive, CD8 effector, and naive) clusters. The decreased infiltration of CD8exh and CD4CTL cells was strongly associated with the repression of MHC class II. Notably, this association was not limited to patients harboring CMG mutations (ie, CREBBP, EZH2, and KMT2D), suggesting that other alterations can obtain similar effect.45 Altogether, these data support the paramount importance of the genetic and immune composition of the TME in FL and provide evidence for their complementary role to better identify high-risk patients.

Imaging biomarkers for POD24

Since 2014 PET scanning has been recommended as the imaging of choice for initial staging and response assessment of FL.46,47 Quantitative parameters such as SUV and total metabolic tumor volume (TMTV) have been investigated as putative prognosticators, but data remain conflicting. Several studies suggested that high baseline SUVmax (bSUVmax) can identify aggressive lymphoma;48-52 however, no consensus has been achieved on the optimal SUV cutoff to detect HT.50-52 A large retrospective study found that bSUVmax greater than 18 was associated with a higher HT rate,53 while a subanalysis of the GALLIUM trial did not find a correlation between bSUVmax and transformation despite the immunochemotherapy backbone.54 This apparent contrast may in part be due to the low number of events (n = 15), the inclusion of only a subset of patients with bPET (46%), and the consistent number of those who were withdrawn or lost to follow-up in the GALLIUM study.54 Additional controversy is linked to the prognostic value of PET, with discordant results reported by several groups (Table 4).53-59 It is possible that bSUV is not necessarily reflective of highly proliferative disease but may be linked to the TME. This concept is supported by a recent study investigating the correlation between FDG-PET parameters and CD4 and CD8 expression.60 SUVmax seemed directly correlated with higher CD4 and CD8 T-cell infiltration than intratumoral B cells. In contrast, increasing TMTV values are associated with a progressively lower intratumoral T-cell infiltration and the concomitant increase of malignant B cells.60 These data are in line with prior studies identifying low immune cell infiltration as a predictor of POD24 and may partially explain the contradictory results between different F-fludeoxyglucose–PET parameters.42,43 However, more investigation is needed to untangle the biological underpinnings of SUV and its prognostic relevance.

Prognostic value of baseline SUVmax in FL

| Study . | Type of study . | No patients . | HT . | PFS . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strati et al53 | Retrospective | 346 | 18 pts (5%) with HT: 12 HT in SUVmax < 18 and 6 (11%) in SUVmax > 18 (P = .04) | Inferior OS in SUVmax >18 |

| GALLIUM54 | Clinical trial | 549 | 15 pts (2.7%) with HT: no difference in SUVmax | No association of bSUVmax with PFS |

| PET in PRIMA55 | Retrospective | 58 | No pts with HT | No association of bSUVmax with PFS |

| FOLLCOLL56 | Retrospective | 181 | 2 pts with HT | Inferior PFS in SUVmax < 9.4, no difference in OS |

| RELEVANCE58 | Clinical trial | 406 | No evaluated | No association of bSUVmax with PFS |

| Trotman et al59 | Clinical trials | 439 | Not reported | Inferior OS in PET+ |

| Study . | Type of study . | No patients . | HT . | PFS . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strati et al53 | Retrospective | 346 | 18 pts (5%) with HT: 12 HT in SUVmax < 18 and 6 (11%) in SUVmax > 18 (P = .04) | Inferior OS in SUVmax >18 |

| GALLIUM54 | Clinical trial | 549 | 15 pts (2.7%) with HT: no difference in SUVmax | No association of bSUVmax with PFS |

| PET in PRIMA55 | Retrospective | 58 | No pts with HT | No association of bSUVmax with PFS |

| FOLLCOLL56 | Retrospective | 181 | 2 pts with HT | Inferior PFS in SUVmax < 9.4, no difference in OS |

| RELEVANCE58 | Clinical trial | 406 | No evaluated | No association of bSUVmax with PFS |

| Trotman et al59 | Clinical trials | 439 | Not reported | Inferior OS in PET+ |

To overcome the limit of SUVmax that may derive from a single lesion, TMTV was conceived to represent the overall tumor burden. A cutoff of 510 cm3 or greater in pretreatment PET was identified as predictor of inferior PFS in the FOLLCOLL analysis and confirmed in the GALLIUM study after implementation with a fully automated TMTV calculation.61,62 Recently, baseline TMTV has shown to be a strong prognosticator of POD24 and outcome in FL, and when combined with FLIPI score, it can identify a high-risk patient group. However, its impact is primely observed in patients treated with R-chemotherapy, while it was not significant in those who received an R2 regimen (rituximab plus lenalidomide).58 It should be noted that TMTV is not regularly used in clinical practice. To allow the dissemination of this tool, automated deep-learning algorithms are needed to reduce the calculation time and increase reproducibility. Until this is done, TMTV remains restricted to clinical research.

Recent evidence has emerged on the role of postinduction PET scan, alone or combined with minimal residual disease (MRD) assessment to improve early prediction of POD24.63,64 Notably, PET and MRD analysis seem to be independent and complementary prognostic tools in FL. In the FOLL12 trial, MRD was assessed by quantitative reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction with BCL2/IGH consensus primers in peripheral blood and bone marrow. PET and MRD positivity were independently associated with a higher risk of POD24 (HR, 5.61; 95% CI, 2.59-12.1 and HR, 2.37; 95% CI, 1.15-4.84, respectively) and poor outcome. MRD positivity in the context of PET negativity outperformed PET assessment and predicted inferior prognosis comparably to PET-positive patients.64 In the RELEVANCE trial, cell-free DNA (cfDNA) was used to detect MRD from patient serum based on a captured-DNA custom panel. At the 6.4-year follow-up, cfDNA-positive patients had a median PFS of 37 months vs nonreached in cfDNA-negative patients (P = .009). This was similar in PET-positive and PET-negative patients (34 months vs nonreached, P < .001). Regarding POD24, cfDNA and PET had comparable positive predictive value (91.7% and 93.3%, respectively) and negative predictive value (46.7% and 45.0%, respectively); however, their predictive value significantly increased when combined (91.5% and 85.7%).63 Prospective and systemic validation of the predictive role of MRD analysis in FL is warranted. Moreover, the prognostic complementarity of MRD and PET urges consideration of their combined incorporation in future clinical trials and raises the question of whether they should be considered as end points for studies in FL.

CLINICAL CASE (continued)

The patient's scan revealed disease recurrence involving several sites in supra- and infradiaphragmatic areas, with an SUV ranging from 4.3 to 11.5. What is your concern for transformation, and how would you approach management?

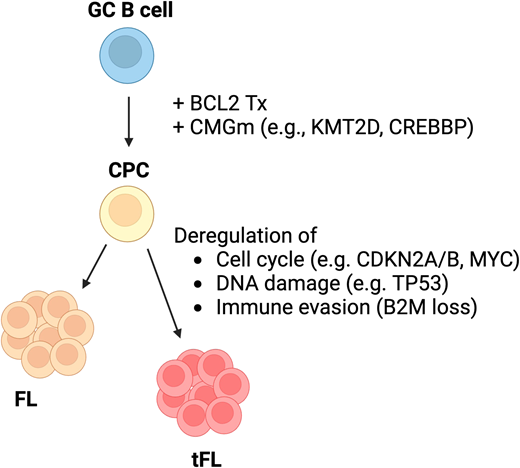

Histologic transformation

The HT of an aggressive lymphoma, most commonly diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), increases steadily over time, occurring in approximately 2% of FL patients per year, with a 30% to 50% 5-year survival.65 We and others have recently showed that HT within 24 months of immunochemotherapy has an especially poor prognosis.66-68 First-line therapy seems to influence the incidence of HT at the time of POD24, with a higher risk in patients treated with BR and with obinutuzumab compared to other immunochemotherapy strategies.6,8 In a retrospective study from BC Cancer, treatment with BR was associated with a decreased overall incidence of POD24 (13% of patients), yet in this cohort, the majority of POD24 patients (76%) had HT and a significantly inferior outcome, with a 2-year OS of 38% (95% CI, 20-55).8 However, in the GALLIUM study a similar proportion of HT occurred in obinutuzumab- vs rituximab-based treatment (11 out of 57 [19.3%] with obinutuzumab compared to 19 out of 98 [19.4%] with rituximab].6 More frequent use of initial staging with PET may contribute to these observations. Batlevi and colleagues reported that pretreatment PET staging reduced the prognostic impact of POD24 by identifying patients suspected to have HT at diagnosis, who may be treated differently.69

Several retrospective studies (many ongoing) propose that HT is the sole driver of adverse outcomes in patients experiencing POD24.66-68 Perhaps the most crucial limitation to clarify this question is the paucity of biopsies at POD24 to accurately determine HT rates. A cohort from the GELTAMO group reported that even without HT, POD24 with retained FL histology and high-risk FLIPI still had higher excess mortality compared to non-POD24 cases (10-year survival, 80% vs 93%).67 In a subset analysis of the GALLIUM study limited by very few biopsies at POD24, patients who relapsed within 12 months with retained FL histology had similarly poor outcomes as those with HT, suggesting that HT alone may not account for all differences in mortality.54 In contrast, a large retrospective study from Memorial Sloan Kettering reported that patients with POD24 and retained FL had outcomes similar to those recurring after 24 months.68 Ongoing maturation and final analyses of these and other studies are likely to shed additional insight into some pivotal questions: does the use of R-CHOP in the frontline setting treat occult lymphoma and mitigate HT in POD24? To what degree does first-line treatment with BR drive HT? Is POD24 emerging as an intermediate-risk factor characterized by worse OS compared to a non-POD24 group but better OS compared to those with POD24 and HT?

The pathogenesis of transformation has only been partially characterized to date. The dominant clone of transformed FL (tFL) seems to arise from a CPC after acquiring additional genetic mutations following a divergent evolution (Figure 3).20 The 2 most prominent altered programs in the CPC involve apoptosis and epigenetic modification (eg, BCL2, KMT2D, CREBBP), while tFL frequently harbors alterations of genes regulating the cell cycle (eg, CDKN2A/B and MYC) and DNA damage (eg, TP53), even though a specific genetic lesion has not been identified yet.20,70,71 tFL has a unique genomic landscape characterized by shared alterations with DLBCL as well as lesions that are uncommon in de novo DLBCL.20 Thus, it is possible that this distinct biology may account for the reduced response to therapy. A subsequent study further dissected the clonal dynamic of tFL compared with early progression.72 Interestingly, the tFL clone was rare or absent at diagnosis but eventually expanded and became dominant in the transformed tissues. In contrast, the clones identified in POD24 specimens were already present at diagnosis. The most frequently mutated genes in tFL were confirmed to affect genes regulating the cell cycle (eg, CCND3), DNA damage (eg, TP53), and immune response (eg, B2M), while those in early progressors were associated with the S-G2-M stages of the cell cycle (eg, BTG1, MKI67) and terminal differentiation (eg, XBP1), suggesting the disruption of different biological processes.72 This study had several limitations, including the small sample size and modest clonal detection obtained with bulk sequencing. Therefore, several questions regarding HT remain unanswered. Maybe one of the most important is whether the tFL clone is present at diagnosis or develops subsequently and which are tFL-specific mutations (if any).

CLINICAL CASE (continued)

The patient underwent a biopsy of the most hypermetabolic inguinal lymph node; the SUV was 11.5. This demonstrated grade 3A FL. She enrolled in a clinical trial, SWOG 1608 (NCT03269669), randomizing patients with POD24 FL to obinutuzumab with lenalidomide, bendamustine, CHOP chemotherapy (depending on the first line), or umbralisib. The patient was randomized to the lenalidomide-obinutuzumab arm (the umbralisib arm was stopped early after the withdrawal of PI3kinase inhibitors for treatment of relapsed FL). At the conclusion of therapy, her PET scan demonstrated a CR. She remains in CR and is doing well.

Perspectives on best practice to approach POD24

POD24 remains an adverse prognostic marker of survival in FL and should be considered a factor in treatment planning after frontline therapy. Biopsy at first relapse of FL, particularly at POD24, is an essential component for treatment choice.4,5 Ideally, participation in a clinical trial is encouraged when available given the absence of standard management currently based on expert best practices. Novel therapeutic approaches including CAR T-cell therapy and bispecific antibodies have shown promise in this group, with an overall response rate of 80% to 92%. Half of these patients have remain in remission after 23 months.73,74 Outside of clinical trial options, younger and fit patients have historically been considered for salvage chemotherapy followed by consolidative autologous stem cell transplant. When considering the second line, non–cross-resistant immunochemotherapy regimens are preferred (eg, BR after R-CHOP or vice versa).10 Alternatively, target therapies (eg, tazemetostat, zanubrutinib-obinutuzumab, lenalidomide-rituximab) achieve a 60% to 80% overall response rate but have a modest PFS.75-78

Conclusion

Over the last decade, our understanding of the molecular underpinnings of FL have shifted from a tumorcentric prospective to a more comprehensive view of lymphoma within its TME. There is growing knowledge of how mutations affecting lymphoma cells deregulate key genes involved in cell proliferation, survival, and immune response, ultimately driving lymphomagenesis through a combined proliferative advantage and immune escape. There are still large gaps in our knowledge of the mechanisms driving POD24 and POD24 with HT, and by extension how to effectively intervene therapeutically. Considerating the complete picture of FL with POD24 will lead to novel therapies and may usher in the opportunity for cure.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (1K08CA279652), the Lymphoma Research Foundation (LSRMP #818463; CDA #1020588), the American Society of Hematology (ASH RTAF and Scholar Award), the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO YIA), the Mayo Clinic Center for Individualized Medicine, and the Gerstner Family Career Development Award.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure

Patrizia Mondello: no competing financial interests to declare.

Carla Casulo: no competing financial interests to declare.

Off-label drug use

Patrizia Mondello: none to disclose.

Carla Casulo: none to disclose.