Learning Objectives

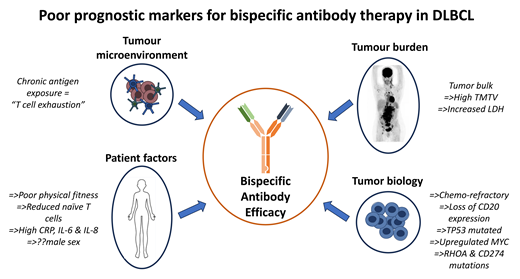

Recognize that bispecific antibody failure is the result of a complex interplay between patient factors, disease characteristics, and the immune system

Understand that future research should focus on optimal drug sequencing, responses in biological subgroups, and methods to reinvigorate exhausted T cells

CLINICAL CASE

A 35-year-old woman with stage III, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) who relapsed within 12 months of frontline rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisolone (R-CHOP) chemotherapy, received second-line CD19-directed autologous chimeric antigen receptor T-cell (CAR-T) therapy with R-gemcitabine, dexamethasone, and cisplatin bridging. Day 30 post CAR-T positron emission tomography (PET) imaging demonstrated bulky stage IV disease progression. Secondary to tumor burden and prior therapy toxicity, the patient's Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status was 2. She was considered for third-line CD3/CD20-directed bispecific antibody (BsAb) treatment.

Introduction

CD3/CD20 BsAbs redirect and recruit T cells to their target; CD20 expressing lymphoma cells. These agents have demonstrated some of the most promising results in relapsed/refractory DLBCL to date, with complete responses demonstrated in 35% to 40% of patients with durable remissions observed.1-4 They offer an off-the-shelf T-cell-activating therapy with acceptable toxicity. Based on phase 2 study results, two BsAbs, epcoritamab and glofitamab, were granted FDA approval in 2023. Unfortunately, despite the perceived success of these therapies, the majority of patients still succumb to their disease, and predictive biomarkers of response and failure are desperately needed. Here, we review the current literature on prognostic and predictive markers of failure in BsAb treatment.

Patient factors

Demographics

Baseline immunity

Patients receiving standard-care BsAb have already received multiple lines of immunosuppressive treatment. Prior chemotherapy may have deleterious effects on T-cell numbers, with preferential reductions in naïve T cells, which are thought to be more efficacious in the setting of BsAbs.6 In addition, chemotherapy can induce T-cell expression of immune checkpoints, rendering them anergic in the setting of BsAb engagement.7 Data demonstrate that baseline CRP and IL-6 and IL-8 levels, which are crucial to adaptive immune regulation, were higher in the plasma of nonresponding patients. These factors portend a preexisting unfavorable environment for T-cell engagement and killing, thus likely contributing to BsAb failure.8

Acquired T-cell dysfunction

When T cells are chronically exposed to an antigen, they lose their integral effector function and enter a state of “exhaustion” through co-expression of inhibitory molecules, such as programmed cell death protein 1. This T-cell hypo-responsiveness is characterized by altered transcription with loss of function related to cytokine secretion, proliferation, and cytotoxicity.9,10 Philipp et al reported T-cell exhaustion during continuous exposure to BsAb, which contributes to therapeutic resistance in in vitro models. This was corroborated in a clinical BsAb study, where those with relapse retaining CD20 expression showed highly expanded yet exhausted T cells in their tumor microenvironment, with the abundance of exhausted CD8+ clones predicting response failure.11 Interestingly, in preclinical models, treatment-free intervals were associated with functional reinvigoration of T cells and transcriptional reprogramming.10

Tumor characteristics

Tumor bulk

Pretreatment elevated lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), a surrogate marker for tumor bulk and activity, heralds a poor prognosis in DLBCL and is included in many prognostic indices. Similarly, baseline high LDH and tumor bulk both represent adverse risk in patients receiving BsAb.5 Further to this, increasing evidence demonstrates baseline fluorodeoxyglucose PET/computed tomography (FDG-PET/CT)–derived metabolic tumor volume impacts prognosis in BsAb-treated lymphoma patients. Using a semiautomatic method, glofitamab-treated patients with a baseline total metabolic tumor volume (TMTV) above or equal to the median demonstrated inferior progression-free survival (PFS) of 16.8% compared with 50.1% when baseline TMTV was below the median.12

Response to prior therapy

Tumor biology

BsAb activity has been noted across varying immunohistochemistry CD20 expression levels, except for levels <10% where objective responses may be reduced.8,13 While acquired reduced transcription or gain-of-truncating mutations of CD20 are commonplace in progressors on BsAb, they are rare prior to commencing BsAb.11,13 This suggests other genomic factors contribute to evading BsAb success. Bröske et al demonstrated that tumors with upregulated MYC targets and downregulated TP53 target signatures are less likely to achieve a complete response.8 In addition, mutations and/or deletions in genes associated with cell survival (RHOA) and immunomodulation (CD274) were associated with an inferior overall survival (OS).14

A summary of emerging adverse prognostic markers in BsAb therapy is presented in Table 1.

Emerging adverse prognostic markers in bispecific antibody therapy

| Poor prognostic marker . | Cohort . | Bispecific antibody analyzed . | Number . | Timepoint assessed . | Outcome measure affected . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ECOG >0 | Retrospective5 | CD20/CD3 | N = 143 | ≥1 prior line of therapy | Inferior OS |

| Male sex | Prospective1,2 | • Glofitamab • Epcoritamab | • N = 154 • N = 157 | >1 prior line of therapy | Lower CR rate |

| Chemotherapy refractoriness | Prospective1 + Retrospective5 | • Glofitamab • CD20/CD3 | • N = 154 • N = 104 | ≥1 prior line of therapy | • Lower CR rate • Inferior PFS/OS |

| High inflammatory markers: IL-6, IL-8, CRP | Prospective8 | Glofitamab | N = 119 | ≥1 prior line of therapy | Lower CR rate |

| Increased LDH | Retrospective5 | CD20/CD3 | N = 104 | ≥1 prior line of therapy | Inferior PFS/OS |

| TMTV ≥ median | Retrospective12 | Glofitamab | N = 144 | >1 prior line of therapy | Inferior PFS |

| Tumor: <10% CD20 expression | Retrospective13 | Mosunetuzumab | N = 161 | ≥2 prior therapies | Reduced ORR |

| Tumor: molecular aberrations MYC, TP53, RHOA, CD274, GNAI2 | Retrospective8,14 | • Glofitamab • CD20/CD3 | N = 33 N = 36 | >1 prior line of therapy | • Reduced ORR • Inferior PFS/OS |

| TME: increased “exhausted” CD8 T cells | Retrospective11 | CD20/CD3 | N = 7 | >1 prior line of therapy | Higher relapse rate |

| Poor prognostic marker . | Cohort . | Bispecific antibody analyzed . | Number . | Timepoint assessed . | Outcome measure affected . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ECOG >0 | Retrospective5 | CD20/CD3 | N = 143 | ≥1 prior line of therapy | Inferior OS |

| Male sex | Prospective1,2 | • Glofitamab • Epcoritamab | • N = 154 • N = 157 | >1 prior line of therapy | Lower CR rate |

| Chemotherapy refractoriness | Prospective1 + Retrospective5 | • Glofitamab • CD20/CD3 | • N = 154 • N = 104 | ≥1 prior line of therapy | • Lower CR rate • Inferior PFS/OS |

| High inflammatory markers: IL-6, IL-8, CRP | Prospective8 | Glofitamab | N = 119 | ≥1 prior line of therapy | Lower CR rate |

| Increased LDH | Retrospective5 | CD20/CD3 | N = 104 | ≥1 prior line of therapy | Inferior PFS/OS |

| TMTV ≥ median | Retrospective12 | Glofitamab | N = 144 | >1 prior line of therapy | Inferior PFS |

| Tumor: <10% CD20 expression | Retrospective13 | Mosunetuzumab | N = 161 | ≥2 prior therapies | Reduced ORR |

| Tumor: molecular aberrations MYC, TP53, RHOA, CD274, GNAI2 | Retrospective8,14 | • Glofitamab • CD20/CD3 | N = 33 N = 36 | >1 prior line of therapy | • Reduced ORR • Inferior PFS/OS |

| TME: increased “exhausted” CD8 T cells | Retrospective11 | CD20/CD3 | N = 7 | >1 prior line of therapy | Higher relapse rate |

CR, complete response; CRP, C-reactive protein; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; IL, interleukin; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; N, number; ORR, overall response rate; OS, overall survival; PFS, progression-free survival; TME, tumor microenvironment; TMTV, total metabolic tumor volume.

CLINICAL CASE (continued)

Our patient received CD3/CD20 BsAb treatment but unfortunately experienced primary disease progression; chemo-refractoriness, poor performance status, high tumor burden, and T-cell dysfunction due to prior multiple therapeutic lines were all likely contributing factors. She was subsequently considered for a phase 1 trial.

Future research directions

Despite the excellent promising results of BsAb in relapsed/ refractory DLBCL, a minority achieve complete responses, and relapse remains a significant issue. Although our scientific knowledge is expanding, a deep understanding of the intrinsic mechanisms of action for BsAbs is still lacking. This is partly due to the molecular heterogeneity of DLBCL and the complex interplay between the disease, the immune system, and therapy. Evaluating these therapies earlier in the disease course, when host immunity is more robust, is being explored. Additionally, synergistic combination treatments with chemotherapy, antibody- drug conjugates, and immunomodulatory agents are being investigated with the hope of achieving deeper responses and fewer relapses. With the aim of circumventing T-cell exhaustion and enhancing tumor lysis, next-generation trispecific antibodies are being evaluated in early phase trials. Future research should address uncertainties around the best treatment sequencing, expected responses in biological subgroups, and methods to reinvigorate exhausted T cells, such as co-stimulatory combinations. Additionally, it should prioritize rational, robust translational research to improve outcomes through refined patient selection for BsAb commencement, as well as early identification and preemptive mitigation of resistance.

Recommendation

A full clinical and biomarker risk assessment should be performed on every DLBCL patient at relapse for the purposes of clinical annotation and prognostication; currently, however, this information should not be used to change management. All appropriate and eligible patients should be considered for BsAb therapy regardless of risk profile (level of evidence: 2C).

Conflict-of-interest disclosure

Allison Barraclough: honoraria: Roche, BeiGene, Novartis, Gilead.

Eliza A. Hawkes: research funding: BMS, Merck KgaA, AstraZeneca, Roche; advisory board: Roche, Antengene, BMS, Gilead, AstraZeneca; speakers bureau: Regeneron, Janssen, AstraZeneca (institution).

Off-label drug use

Allison Barraclough: Nothing to disclose.

Eliza A. Hawkes: Nothing to disclose.