Abstract

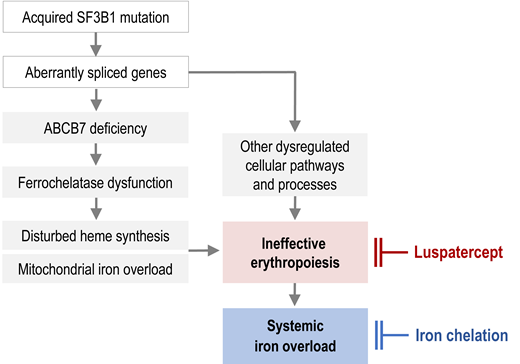

Besides transfusion therapy, ineffective erythropoiesis contributes to systemic iron overload in myelodysplastic syndromes with ring sideroblasts (MDS-RS) via erythroferrone-induced suppression of hepcidin synthesis in the liver, leading to increased intestinal iron absorption. The underlying pathophysiology of MDS-RS, characterized by disturbed heme synthesis and mitochondrial iron accumulation, is less well understood. Several lines of evidence indicate that the mitochondrial transporter ABCB7 is critically involved. ABCB7 is misspliced and underexpressed in MDS-RS, due to somatic mutations in the splicing factor SF3B1. The pathogenetic significance of ABCB7 seems related to its role in stabilizing ferrochelatase, the enzyme incorporating iron into protoporphyrin IX to make heme. Although iron-related oxidative stress is toxic, many patients with MDS do not live long enough to develop clinical complications of iron overload. Furthermore, it is difficult to determine the extent to which iron overload contributes to morbidity and mortality in older patients with MDS, because iron-related complications overlap with age-related medical problems. Nevertheless, high-quality registry studies showed that transfusion dependency is associated with the presence of toxic iron species and inferior survival and confirmed a significant survival benefit of iron chelation therapy. The most widely used iron chelator in patients with MDS is deferasirox, owing to its effectiveness and convenient oral administration. Luspatercept, which can reduce SMAD2/SMAD3-dependent signaling implicated in suppression of erythropoiesis, may obviate the need for red blood cell transfusion in MDS-RS for more than a year, thereby diminishing further iron loading. However, luspatercept cannot be expected to substantially reduce the existing iron overload.

Learning Objectives

Examine the roles of chelation and luspatercept in managing iron overload in acquired sideroblastic anemias and MDS

Evaluate the indication for iron chelation therapy and luspatercept treatment in patients with MDS-RS

Understand the pathomechanism of systemic and mitochondrial iron overload in MDS with ring sideroblasts

CLINICAL CASE

A 69-year-old man, previously in good health, presents with anemia (hemoglobin 9.1 g/dL) and dyspnea on exertion. Three years ago, his hemoglobin level was 13 g/dL. His white blood count (WBC) is 4900/µL, WBC differential is inconspicuous, and platelet count is 195 000/µL. Although he never received transfusions, his serum ferritin (SF) level is elevated (1400 ng/mL). The transferrin saturation (TSAT) is 38%. Vitamin B12 and folate levels are normal, and renal function is not significantly impaired. His serum erythropoietin level is 140 IU/mL. The bone marrow biopsy and aspirate show expanded erythropoiesis and pathological ring sideroblasts. The karyotype is normal.

Acquired sideroblastic anemias

Not all patients with acquired sideroblastic anemia (SA) have a clonal bone marrow disorder. Reversible causes of SA include heavy metal poisoning (lead or arsenic), zinc overdose, copper deficiency, vitamin B6 deficiency, and alcohol abuse. Certain drugs like chloramphenicol, isoniazid, or linezolid may also cause SA by disturbing heme biosynthesis (see Table 1).

Causes of reversible acquired sideroblastic anemia

| Alcohol abuse | Alcohol and its metabolite, acetaldehyde, can inhibit several steps of the heme synthetic pathway. Mitochondrial iron accumulation seems to reflect an imbalance between the large amounts of iron imported into mitochondria for heme synthesis, and insufficient production of protoporphyrin IX to incorporate the iron. |

| Vitamin B6 deficiency | Vitamin B6 (pyridoxal phosphate) is a cofactor of erythroid 5-aminolevulinate synthase (ALAS2), the first enzyme of porphyrin synthesis. |

| Lead poisoning | Lead inhibits ferrochelatase and most of the other enzymes in the heme biosynthetic pathway to varying degrees. |

| Arsenic poisoning | Arsenic causes mitochondrial dysfunction, increased intracellular ROS, mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) damage, and decreased activity of cytochrome c oxidase (COX). |

| Copper deficiency | Copper is an essential component of COX, ie, complex IV of the mitochondrial respiratory chain. Copper deficiency can thus impair mitochondrial O2 consumption and may lead to oxidation of Fe2+ to Fe3+, which cannot be used for heme synthesis. |

| Zinc overdose | Copper deficiency can be induced by excessive zinc ingestion because large quantities of ingested zinc interfere with intestinal copper absorption. |

| Isoniazid | Isoniazid deprives ALAS2 of pyridoxal phosphate and therefore inhibits porphyrin synthesis. |

| Chloramphenicol | This antibiotic not only inhibits bacterial but also mitochondrial protein synthesis via its action on the large ribosomal subunit of the organelle, thereby impairing the synthesis of respiratory chain subunits encoded by the mitochondrial genome. |

| Linezolid | Linezolid also inhibits mitochondrial protein synthesis by binding to human mitochondrial 16S ribosomal RNA. Certain mitochondrial haplogroups are more susceptible to this effect than others. |

| Alcohol abuse | Alcohol and its metabolite, acetaldehyde, can inhibit several steps of the heme synthetic pathway. Mitochondrial iron accumulation seems to reflect an imbalance between the large amounts of iron imported into mitochondria for heme synthesis, and insufficient production of protoporphyrin IX to incorporate the iron. |

| Vitamin B6 deficiency | Vitamin B6 (pyridoxal phosphate) is a cofactor of erythroid 5-aminolevulinate synthase (ALAS2), the first enzyme of porphyrin synthesis. |

| Lead poisoning | Lead inhibits ferrochelatase and most of the other enzymes in the heme biosynthetic pathway to varying degrees. |

| Arsenic poisoning | Arsenic causes mitochondrial dysfunction, increased intracellular ROS, mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) damage, and decreased activity of cytochrome c oxidase (COX). |

| Copper deficiency | Copper is an essential component of COX, ie, complex IV of the mitochondrial respiratory chain. Copper deficiency can thus impair mitochondrial O2 consumption and may lead to oxidation of Fe2+ to Fe3+, which cannot be used for heme synthesis. |

| Zinc overdose | Copper deficiency can be induced by excessive zinc ingestion because large quantities of ingested zinc interfere with intestinal copper absorption. |

| Isoniazid | Isoniazid deprives ALAS2 of pyridoxal phosphate and therefore inhibits porphyrin synthesis. |

| Chloramphenicol | This antibiotic not only inhibits bacterial but also mitochondrial protein synthesis via its action on the large ribosomal subunit of the organelle, thereby impairing the synthesis of respiratory chain subunits encoded by the mitochondrial genome. |

| Linezolid | Linezolid also inhibits mitochondrial protein synthesis by binding to human mitochondrial 16S ribosomal RNA. Certain mitochondrial haplogroups are more susceptible to this effect than others. |

CLINICAL CASE (continued)

None of the reversible causes of SA are identified in this patient, whose age suggests that myelodysplastic syndrome with ring sideroblasts (MDS-RS) is the most likely diagnosis. The suspicion is confirmed by mutation analysis, revealing an SF3B1 (K700E) mutation with a variant allele frequency of 42%. The patient is not keen to receive blood transfusions and asks about treatment options addressing the underlying cause of his health problem.

Pathophysiology of anemia and iron overload in MDS-RS

While the above-mentioned reversible conditions can be treated by removing a noxious agent or ameliorating a deficiency, causal treatment for acquired SA in the context of MDS is not available, and our knowledge of the mechanism of ring sideroblast formation in MDS is still incomplete. The patient's systemic iron overload is easier to explain.

Mechanism of systemic iron overload

Ineffective erythropoiesis, a hallmark of MDS, is particularly pronounced in patients with ring sideroblasts.1,2 By sending a signal to the liver to suppress hepcidin synthesis, ineffective erythropoiesis enhances intestinal iron absorption. This happens in all iron-loading anemias. The long-sought signal was eventually identified as erythroferrone,3 a protein hormone encoded by the ERFE gene and produced by proliferating erythroblasts under the influence of erythropoietin. If the signal is active over a long time, it precipitates systemic iron overload even before the patient becomes transfusion dependent. In the MDS patient population, the lowest hepcidin levels and hepcidin/ferritin ratios were found in patients with ring sideroblasts and SF3B1 mutation,2,4 which may explain their propensity to parenchymal iron loading. While we understand that ineffective erythropoiesis, in concert with transfusion therapy, causes systemic iron overload in MDS-RS, the underlying pathophysiology of disturbed heme synthesis and mitochondrial iron accumulation is less well understood.

Mechanism of mitochondrial iron overload

Erythroblast mitochondria take up large amounts of iron because this is where heme synthesis takes place. However, as soon as ferrochelatase has inserted iron into protoporphyrin IX (the end product of porphyrin synthesis), iron leaves the mitochondria again, now being part of the heme molecule. Heme synthesis is disturbed in MDS-RS. Although protoporphyrin IX is not deficient and ferrochelatase is neither mutated nor underexpressed,5 iron is not properly utilized for heme synthesis and thus accumulates in the mitochondrial matrix.

Comprehensive DNA sequencing revealed that about 80% of patients with MDS-RS have an acquired mutation of SF3B1, a component of the splicing machinery.6 Mutant SF3B1 causes aberrant splicing in a variety of genes and may thus contribute to ineffective erythropoiesis in several ways. Importantly, ABCB7, a transporter in the mitochondrial membrane, is affected by missplicing.7 Prior to the detection of mutant SF3B1, ABCB7 mRNA levels were found to be substantially decreased in MDS-RS.8 Another hint that ABCB7 is implicated in the formation of ring sideroblasts came from germline mutations of ABCB7 causing congenital X-linked SA with ataxia.9 Furthermore, an induced pluripotent stem cell model recently demonstrated that rescue of ABCB7 strongly reduces ring sideroblast formation.10 Apparently, mutant or deficient ABCB7 plays an important role in the pathogenesis of mitochondrial iron accumulation.

ABCB7 is usually characterized as a transporter that exports an unknown product of the iron-sulfur (Fe-S) cluster assembly from the mitochondrial matrix to the cytosol. A defect of ABCB7, by depleting cytosolic aconitase of its Fe-S cluster and converting the enzyme into iron regulatory protein 1 (IRP1), may be sensed as cellular iron deficiency, thus stimulating increased cellular iron uptake. However, that is only part of the truth because ABCB7 is also involved in the biosynthesis of heme in erythroid cells through interaction with ferrochelatase.11 Both ferrochelatase and ABCB7 are part of the mitochondrial heme metabolism complex,12 which comprises several proteins that facilitate substrate channeling and help to coordinate iron and porphyrin metabolism.

ABCB7 is required to stabilize ferrochelatase, which must form a homodimer to be functional. Mammalian ferrochelatase possesses an Fe-S cluster that is needed for stability and function. Posttranslational stability of newly formed ferrochelatase is dramatically decreased during iron deficiency or disturbed Fe-S cluster assembly in the mitochondria.13 Pull-down assays revealed that ABCB7 protein interacts with the carboxy-terminal region of ferrochelatase containing the Fe-S cluster. Importantly, knockdown of ABCB7 leads to significant loss of mitochondrial proteins containing an Fe-S cluster and to decreased stability of ferrochelatase.14

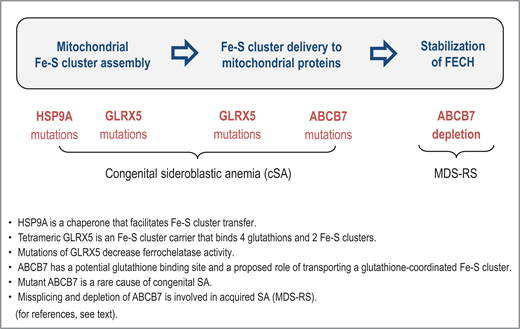

The role of Fe-S cluster incorporation into ferrochelatase is underscored by rare cases of HSP9A and HSCB mutations that cause congenital SA.15,16 Both heat shock proteins are mitochondrial chaperones that facilitate the transfer of nascent [2Fe-2S] clusters to recipient mitochondrial proteins. There are also rare cases of congenital SA with GLRX5 mutations.17,18 Tetrameric glutaredoxin 5 is an Fe-S cluster carrier that binds 4 glutathions and 2 Fe-S clusters, and mutations of GLRX5 decrease the stability of ferrochelatase.19 Interestingly, ABCB7 has a potential glutathione binding site and a proposed role of transporting a glutathione-coordinated Fe-S cluster [2Fe-2S](GS)4.20 As summarized in Figure 1, SA may thus be attributable to problems at different stages of mitochondrial Fe-S cluster assembly and Fe-S cluster delivery to ferrochelatase.

The sideroblastic phenotype can arise from problems at different stages of mitochondrial Fe-S cluster assembly and delivery to ferrochelatase. FECH, ferrochelatase.

The sideroblastic phenotype can arise from problems at different stages of mitochondrial Fe-S cluster assembly and delivery to ferrochelatase. FECH, ferrochelatase.

The evidence mentioned above suggests a mechanism for mitochondrial iron accumulation in acquired (MDS-related) SA as depicted in Figure 2. The diagram indicates that ABCB7 deficiency leads to impaired stabilization of ferrochelatase because ABCB7 fails to provide sufficient support for Fe-S cluster incorporation into ferrochelatase. Consequently, dysfunctional ferrochelatase cannot utilize the iron that is imported into mitochondria for heme synthesis. Iron crosses the inner mitochondrial membrane as Fe2+. If not immediately accepted and processed by ferrochelatase, Fe2+ will autoxidize to Fe3+, thus becoming useless for heme synthesis. According to this model, impaired ferrochelatase protein function plays a pivotal role in producing the sideroblastic phenotype, even though the ferrochelatase gene is neither mutated nor underexpressed.

(A) Involvement of ABCB7 in supporting stability and function of ferrochelatase. (B) Probable mechanism of mitochondrial iron accumulation in acquired (MDS-related) SA (see text for explanation). FECH, ferrochelatase; PPIX, protoporphyrin IX.

(A) Involvement of ABCB7 in supporting stability and function of ferrochelatase. (B) Probable mechanism of mitochondrial iron accumulation in acquired (MDS-related) SA (see text for explanation). FECH, ferrochelatase; PPIX, protoporphyrin IX.

CLINICAL CASE (continued)

Due to ineffective erythropoiesis, the patient has already developed a modest degree of systemic iron overload. Is it time to start iron chelation therapy (ICT)? Since most guidelines suggest starting ICT when SF exceeds 1500 ng/mL, the patient first receives epoetin alfa, which succeeds in avoiding transfusion therapy and raises the hemoglobin to around 10.5 g/dL for 15 months. After relapse, luspatercept is given, achieving another transfusion-free period of 1 year, with hemoglobin levels around 10 g/dL. Thereafter, anemia worsens again, the patient requires transfusion therapy, and SF quickly rises to 1800 ng/mL. Iron chelation with deferasirox (DFX) is started.

Rationale for iron chelation therapy in MDS

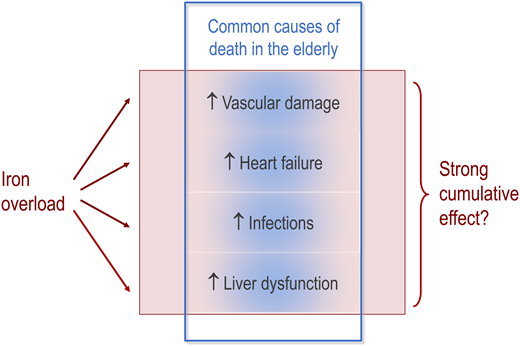

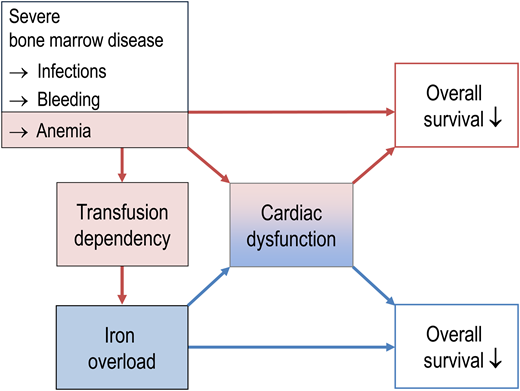

Iron-related oxidative stress is toxic, and widespread subclinical organ dysfunction can result from transfusional iron overload developing in adulthood.21 However, many MDS patients do not live long enough to develop clinical complications of iron overload. Furthermore, it is difficult to determine the extent to which iron overload contributes to morbidity and mortality in older patients with MDS, because iron-related complications overlap with age-related medical problems (Figure 3).

Overlap between iron-related complications and and common age-related problems in older patients with MDS. Even if iron-related complications add up and act as a strong risk factor, their effect may hide behind the common causes of death in older patients. It is therefore difficult to determine the extent to which iron overload contributes to morbidity and mortality in older patients with MDS.

Overlap between iron-related complications and and common age-related problems in older patients with MDS. Even if iron-related complications add up and act as a strong risk factor, their effect may hide behind the common causes of death in older patients. It is therefore difficult to determine the extent to which iron overload contributes to morbidity and mortality in older patients with MDS.

Nevertheless, an SF >1000 ng/mL showed a clear dose-dependent impact on overall survival in patients with low-risk MDS,22 and SF was an independent prognostic factor even if transfusion burden, reflecting the degree of bone marrow failure, was included in multivariate analysis. Similarly, data from the European LeukemiaNet prospective MDS registry indicated that besides transfusion burden, which was the most important prognostic factor, increasing levels of SF had an independent impact on overall survival of transfusion-dependent patients with lower- risk MDS. This registry also found inferior survival rates when labile plasma iron was detectable in patients with lower-risk MDS, whether the patients were transfusion dependent or not.23 An update with a larger number of patients confirmed that transfusion dependency is associated with the presence of toxic iron species and inferior survival.24

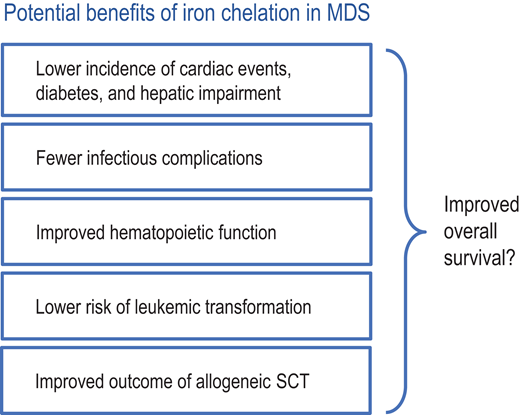

Since ICT provides several potential benefits to patients with transfusion-dependent MDS (Figure 4), it may extend overall survival. This is suggested by multiple retrospective studies, many of which are not totally convincing because patient populations were usually well characterized regarding disease-related parameters and risk factors but not stratified according to performance status. Therefore, fitter patients may have been more likely to receive ICT, thus inflating its benefit. Two registry studies went to great lengths to avoid such bias. The Canadian MDS Registry, which carefully documents performance status and comorbidities, showed a significant survival benefit of ICT when roughly comparable cohorts were analyzed. This finding was corroborated by harnessing several important matching criteria.25 Another thorough analysis comes from the prospective European LeukemiaNet MDS (EUMDS) Registry, which similarly adjusted for relevant prognostic factors and confirmed a significant survival benefit of ICT.26 To address potential problems with time-varying confounding, a further investigation used marginal structural outcome modeling to study the association between ICT using DFX and important clinical outcomes, including survival, in a large US Medicare-based MDS patient cohort. Among patients who received a minimum of 20 blood transfusions, DFX therapy was associated with a significantly reduced risk of death that was proportional to the duration of DFX therapy.27 In a meta-analysis of 9 observational studies, ICT was associated with an overall lower risk of mortality compared with no ICT (adjusted hazard ratio 0.42; 95% CI 0.28-0.62; P < 0.01); however, there was significant heterogeneity across the studies.28 Overall, these studies all point in the same direction, which makes it hard to ignore their results.

Several potential benefits of iron chelation in MDS may lead to extended overall survival. SCT, stem cell transplantation.

Several potential benefits of iron chelation in MDS may lead to extended overall survival. SCT, stem cell transplantation.

The only prospective randomized trial of ICT in MDS is the Telesto study, which showed a significant advantage for DFX vs placebo.29 The primary endpoint of the study was event-free survival, which was measured using a composite primary endpoint of time from randomization to time of first documented nonfatal event (related to cardiac and liver function and transformation to AML) or death. The Kaplan-Meier curves for event-free survival separate after about 2 years, which is plausible because it takes time for iron-related organ damage to develop and, accordingly, for a clinical benefit of ICT to manifest itself.

Practical aspects of iron chelation in MDS

Some “rules of thumb” are offered in Table 2. An excellent, more comprehensive treatise on iron chelation in MDS was recently published in Blood.30 SF levels are generally used to detect iron overload. In addition, TSAT is important, since TSAT levels > 70%-80% can serve as surrogate parameter for the presence of toxic labile plasma iron, which cannot be measured in routine clinical practice. TSAT levels > 70%-80% were found to be a prerequisite for parenchymal iron loading,31 and TSAT > 80% predicts inferior clinical outcomes in MDS.32 Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) should be considered in patients with cardiac comorbidities, since clinical outcomes for MDS may be aggravated by myocardial iron overload, with adverse effects on prognosis (Figure 5). The heart is more vulnerable to iron overload than the liver, with clinically relevant cardiac dysfunction occurring at much lower tissue iron concentrations than clinically relevant liver dysfunction.33 About 18% of MDS patients have cardiac iron overload detectable by MRI.34

Relationship between bone marrow failure, iron overload, and prognosis in patients with MDS. In part, transfusion dependency predicts shortened survival because it reflects hematopoietic insufficiency and its complications like infection, bleeding, and the sequelae of chronic anemia. In addition, transfusion dependency causes iron overload, thereby creating a new medical problem that has its own negative impact on overall survival, partly via cardiac problems.

Relationship between bone marrow failure, iron overload, and prognosis in patients with MDS. In part, transfusion dependency predicts shortened survival because it reflects hematopoietic insufficiency and its complications like infection, bleeding, and the sequelae of chronic anemia. In addition, transfusion dependency causes iron overload, thereby creating a new medical problem that has its own negative impact on overall survival, partly via cardiac problems.

Recommendations for managing iron chelation in patients with MDS

| Confirm iron overload | • Try to determine the number of RBC units transfused so far. • Measure SF and note possible interference by inflammation. • Measure transferrin saturation (if > 70%-80%, toxic labile plasma iron will be present). • MRI can detect cardiac iron overload not suspected from SF measurements. |

| Consider cardiac comorbidities | Only a minority of MDS patients have cardiac iron overload detectable by MRI. However, iron-related oxidative stress can aggravate cardiac comorbidities. The latter should thus be viewed as a supporting argument for iron chelation. |

| Assess the patient‘s prognosis | Candidates for iron chelation should have a life expectancy of at least 1-2 years because it takes time for iron-related organ damage to become clinically significant. |

| Check the indication for iron chelation | If life expectancy is adequate and continued ineffective erythropoiesis or transfusion need is anticipated, most guidelines recommend starting ICT when SF levels exceed 1000 or 1500 ng/mL. |

| Choose an iron chelator | • The oral iron chelator DFX is most widely used (effective, convenient). • The oral iron chelator DFP is most effective in mobilizing cardiac iron. • Continuous parenteral DFO can be considered in combination with DFP to harness a shuttle effect for enhanced removal of cardiac iron. |

| Monitor for important side effects | • DFX dose must be adjusted to GFR in patients with impaired renal function. • When using DFP, perform regular blood counts to detect agranulocytosis. • During DFO and DFX therapy, monitor for visual disturbances and hearing loss. |

| Confirm iron overload | • Try to determine the number of RBC units transfused so far. • Measure SF and note possible interference by inflammation. • Measure transferrin saturation (if > 70%-80%, toxic labile plasma iron will be present). • MRI can detect cardiac iron overload not suspected from SF measurements. |

| Consider cardiac comorbidities | Only a minority of MDS patients have cardiac iron overload detectable by MRI. However, iron-related oxidative stress can aggravate cardiac comorbidities. The latter should thus be viewed as a supporting argument for iron chelation. |

| Assess the patient‘s prognosis | Candidates for iron chelation should have a life expectancy of at least 1-2 years because it takes time for iron-related organ damage to become clinically significant. |

| Check the indication for iron chelation | If life expectancy is adequate and continued ineffective erythropoiesis or transfusion need is anticipated, most guidelines recommend starting ICT when SF levels exceed 1000 or 1500 ng/mL. |

| Choose an iron chelator | • The oral iron chelator DFX is most widely used (effective, convenient). • The oral iron chelator DFP is most effective in mobilizing cardiac iron. • Continuous parenteral DFO can be considered in combination with DFP to harness a shuttle effect for enhanced removal of cardiac iron. |

| Monitor for important side effects | • DFX dose must be adjusted to GFR in patients with impaired renal function. • When using DFP, perform regular blood counts to detect agranulocytosis. • During DFO and DFX therapy, monitor for visual disturbances and hearing loss. |

In general, MDS patients should have a life expectancy of at least 1-2 years to be likely to benefit from ICT. If persistent ineffective erythropoiesis or transfusion need is anticipated, most guidelines recommend starting ICT when SF levels exceed 1500 ng/mL.

A short characterization of approved iron chelators is given in Table 3. Due to its short half-life and need for continuous parenteral infusion, deferoxamine (DFO) is not widely used any more. However, it can be combined with the oral iron chelator deferiprone (DFP) to achieve enhanced removal of cardiac iron, based on a shuttle effect that employs the superior capacity of DFP to mobilize cardiac iron,35 which is then transferred to DFO for excretion. When using DFP, regular blood counts must be carried out to detect agranulocytosis, though the incidence of DFP-induced agranulocytosis is not increased in MDS compared to patients with nonmalignant bone marrow disorders.36 The most widely used iron chelator in patients with MDS is DFX, owing to its effectiveness37 and convenient oral administration. In a fraction of MDS patients, iron chelation with DFX leads to hematologic improvement, probably through diminished oxidative stress in the bone marrow.38 Since DFX decreases renal plasma flow and glomerular filtration rate (GFR), dosage must be adjusted in patients with impaired renal function. Furthermore, patients on DFX therapy should be monitored for visual disturbances and hearing loss.

Short characterization of approved iron chelators

| . | DFO . | DFP . | DFX . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Usual dose | 40 mg/kg/d, SC or IV | 75-100 mg/kg/d PO | 14-28 mg/kg/d PO |

| Plasma half-life | 20 min | 1-3 h | 8-16 h |

| Iron excretion | Urine, fecal | Urine | Fecal |

| Cellular permeability | Lowest | Highest | High |

| Cardiac iron removal | Slow | Effective | Effective |

| Advantages | Longest track record | Cardiac iron removal | 24 h Chelation coverage with single dose |

| Disadvantages | Parenteral administration, LPI suppression only during infusion | Frequent WBC monitoring necessary due to possibility of severe neutropenia | Decreased renal plasma flow and GFR |

| Main side effects | Impaired hearing, visual disturbances, nausea, arthralgia, tachycardia, dyspnea | Nausea, vomiting, neutropenia, agranulocytosis, arthropathy, increased transaminases | Decreased renal function, GI intolerance, hepatic impairment, visual and hearing disturbances |

| . | DFO . | DFP . | DFX . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Usual dose | 40 mg/kg/d, SC or IV | 75-100 mg/kg/d PO | 14-28 mg/kg/d PO |

| Plasma half-life | 20 min | 1-3 h | 8-16 h |

| Iron excretion | Urine, fecal | Urine | Fecal |

| Cellular permeability | Lowest | Highest | High |

| Cardiac iron removal | Slow | Effective | Effective |

| Advantages | Longest track record | Cardiac iron removal | 24 h Chelation coverage with single dose |

| Disadvantages | Parenteral administration, LPI suppression only during infusion | Frequent WBC monitoring necessary due to possibility of severe neutropenia | Decreased renal plasma flow and GFR |

| Main side effects | Impaired hearing, visual disturbances, nausea, arthralgia, tachycardia, dyspnea | Nausea, vomiting, neutropenia, agranulocytosis, arthropathy, increased transaminases | Decreased renal function, GI intolerance, hepatic impairment, visual and hearing disturbances |

GI, gastrointestinal; LPI, labile plasma iron; PO, by mouth; SC, subcutaneously.

Role of luspatercept

Although a recent case report suggests that luspatercept also works in congenital X-linked SA,39 its main role is to improve erythropoiesis in patients with MDS-RS. Luspatercept is a recombinant fusion protein that binds transforming growth factor β (TGF-β) superfamily ligands to reduce the SMAD2/SMAD3-dependent signaling implicated in suppression of erythropoiesis. Luspatercept was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) after the MEDALIST trial,40 a randomized, placebo-controlled, phase 3 clinical trial, demonstrated that patients with very low- to intermediate-risk MDS-RS or MDS/MPN-RS-T (myeloproliferative neoplasia with ring sideroblasts and thrombocytosis) achieved higher rates of transfusion independence when treated with luspatercept (38%) compared to placebo (13%). FDA approval was extended to erythropoiesis stimulating agent-naive patients with very low- to intermediate-risk MDS, irrespective of ring sideroblast status, after the COMMANDS trial41 showed that luspatercept induced higher rates of red blood cell (RBC) transfusion independence for at least 12 weeks with concurrent mean Hb increase of ≥1.5 g/dL (weeks 1-24) than did epoetin alfa (59% vs 38%). Noteworthy, luspatercept was superior to epoetin alfa only in patients with ring sideroblasts (72.5% of the study population) or SF3B1 mutation (60.5% of the study population). The high proportion of such patients in the study explains why the trial met its primary endpoint.

Luspatercept treatment may obviate the need for RBC transfusion for more than a year, thus diminishing further iron loading. However, luspatercept cannot be expected to substantially reduce the existing iron overload. If luspatercept induces a rise in hemoglobin by 2 g/dL, the associated increase in red cell mass, roughly equivalent to 2 RBC units, requires mobilization of about 2 × 200 mg of iron, mainly from macrophages. This amount of storage iron recycled into improved erythropoiesis is small compared to >10 g of iron that accumulates, for instance, over 2 years in a patient with a moderate transfusion requirement of 2 RBC units per month. Accordingly, the MEDALIST trial showed that the mean change from baseline in SF was negligible (−2.7 µg/L averaged over weeks 9-24, and −72.0 µg/L averaged over weeks 33-48).40

By augmenting erythropoiesis and decreasing hepcidin, luspatercept may redistribute iron from macrophages to hepatocytes, as recently shown in patients with transfusion-dependent thalassemia, necessitating the comcomitant use of iron chelators for the effective management of iron overload.42 In the best case, luspatercept increases hemoglobin sufficiently to enable phlebotomies, which are clearly the most efficient way to remove excess iron. If successful in diminishing oxidative stress, they provide an additional opportunity to improve erythropoiesis. If phlebotomies are not feasible, the same goal may be pursued with iron chelation.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure

Norbert Gattermann: Research funding by Takeda. Lecture honoraria by Novartis and Bristol-Myers-Squibb.

Off-label drug use

Norbert Gattermann: nothing to disclose.