Abstract

Peripheral T-cell lymphomas (PTCLs) are a heterogenous yet aggressive group of lymphomas that arise from mature T- or NK-cell precursors. Nodal PTCLs include anaplastic large-cell lymphoma, PTCL not otherwise specified, and follicular helper T-cell lymphomas. Recent advances in understanding these heterogenous diseases have prompted investigation of novel agents to improve on treatment. Brentuximab vedotin, a CD30 antibody-drug conjugate, has been incorporated into frontline treatment regimens of CD30-expressing PTCLs based on the ECHELON-2 trial. Multiple ongoing trials are evaluating the addition of other targeted agents in the frontline and relapsed/refractory setting. These include single-agent brentuximab vedotin, histone deacetylase inhibitors, duvelisib, ruxolitinib, EZH2 inhibitors, and azacitidine, among others. Follicular helper T-cell lymphomas, given frequent mutations in epigenetic regulator genes, may preferentially respond to agents such as histone deacetylase inhibitors, EZH2 inhibitors, and hypomethylating agents. As these therapies evolve in their use for both relapsed/refractory disease and then into frontline treatment, subtype-specific therapy will likely help personalize care for patients with PTCL.

Learning Objectives

Review common types of peripheral T-cell lymphomas and updates in classification of follicular helper T-cell lymphomas

Explain the mechanism, rationale, and data supporting use of novel agents in the frontline and relapsed/ refractory settings

Explore novel agents actively being investigated in clinical trials

CLINICAL CASE

A 52-year-old man presents with fatigue, night sweats, rash, and peripheral adenopathy. Laboratory assessment shows anemia (hemoglobin 9.2 g/dL) and elevated serum lactate dehydrogenase (380 U/L). Fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT) shows 2 to 3 cm axillary, mediastinal, inguinal, and retroperitoneal lymphadenopathy. Excisional biopsy of an axillary lymph node reveals atypical lymphocytes expressing CD3, CD5, CD10, BCL6, PD-1, and ICOS. Bone marrow biopsy shows 10% involvement with lymphoma. He is diagnosed with nodal follicular helper T-cell (TFH) lymphoma, angioimmunoblastic subtype.

Introduction

Peripheral T-cell lymphomas (PTCLs) are a heterogenous, generally aggressive group of lymphomas that arise from either mature T- or NK-cell precursors, constituting less than 15% of all non-Hodgkin lymphomas in adults.1 The most common subtypes recognized by both the World Health Organization and International Consensus Classification include anaplastic large-cell lymphoma (ALCL), TFH lymphomas, peripheral T-cell lymphoma, not otherwise specified (PTCL-NOS), primary intestinal T-cell lymphomas, extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma, and hepatosplenic T-cell lymphoma. Nodal PTCLs, including PTCL-NOS, ALCL, and TFH lymphomas, are the most common subtype in Western populations and the focus of this review.

Per the World Health Organization classification, lymphomas derived from TFH cells are distinguished by expression of 2 of the following markers by immunohistochemistry: BCL6, CD10, PD-1, CXCL13, and ICOS. Based on histology, these are further differentiated into nodal TFH lymphoma angioimmunoblastic-type, nodal TFH lymphoma follicular-type, and nodal TFH lymphoma, not otherwise specified. TFH lymphomas carry recurrent genetic abnormalities, including mutations in TET2, IDH2, DNTM3A, and RHOA, suggesting convergent biology.2 PTCL-NOS remains a diagnosis of exclusion, although there is increasing understanding of prognostic subtypes (eg, TBX21, GATA3 mutations).

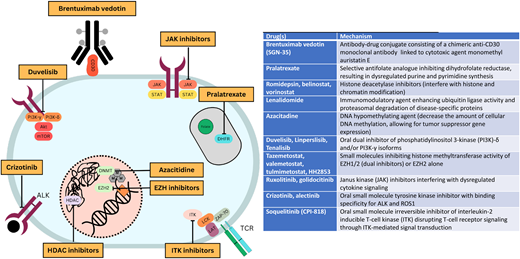

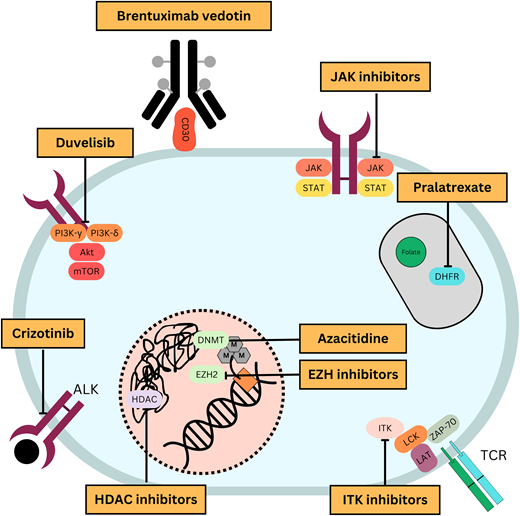

Through an improving understanding of disease biology comes an opportunity to strategically incorporate novel therapies into treatment paradigms (Figure 1). With this goal, multiple novel agents have been studied in PTCL (Table 1). This article highlights therapy approaches using novel agents in the frontline and relapsed/refractory settings.

Mechanisms of action of commonly used novel agents for treatment of PTCLs.

Selected novel agents that have been studied for treatment of PTCLs in the frontline or relapsed/refractory settings

| Drug(s) . | Mechanism . |

|---|---|

| Brentuximab vedotin (SGN-35) | Antibody-drug conjugate consisting of a chimeric anti-CD30 monoclonal antibody linked to cytotoxic agent monomethyl auristatin E |

| Pralatrexate | Selective antifolate analogue inhibiting dihydrofolate reductase, resulting in dysregulated purine and pyrimidine synthesis |

| Romidepsin, belinostat, vorinostat | Histone deacetylase inhibitors (interfere with histone and chromatin modification) |

| Lenalidomide | Immunomodulatory agent enhancing ubiquitin ligase activity and proteasomal degradation of disease-specific proteins |

| Azacitidine | DNA hypomethylating agent (decrease the amount of cellular DNA methylation, allowing for tumor suppressor gene expression) |

| Duvelisib, linperlisib, tenalisib | Oral dual inhibitor of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)-δ and/or PI3K-γ isoforms |

| Tazemetostat, valemetostat, tulmimetostat, HH2853 | Small molecules inhibiting histone methyltransferase activity of EZH1/2 (dual inhibitors) or EZH2 alone |

| Ruxolitinib, golidocitinib | Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors interfering with dysregulated cytokine signaling |

| Crizotinib, alectinib | Oral small-molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitor with binding specificity for ALK and ROS1 |

| Soquelitinib (CPI-818) | Oral small-molecule irreversible inhibitor of interleukin-2 inducible T-cell kinase (ITK) disrupting T-cell receptor signaling through ITK-mediated signal transduction |

| Drug(s) . | Mechanism . |

|---|---|

| Brentuximab vedotin (SGN-35) | Antibody-drug conjugate consisting of a chimeric anti-CD30 monoclonal antibody linked to cytotoxic agent monomethyl auristatin E |

| Pralatrexate | Selective antifolate analogue inhibiting dihydrofolate reductase, resulting in dysregulated purine and pyrimidine synthesis |

| Romidepsin, belinostat, vorinostat | Histone deacetylase inhibitors (interfere with histone and chromatin modification) |

| Lenalidomide | Immunomodulatory agent enhancing ubiquitin ligase activity and proteasomal degradation of disease-specific proteins |

| Azacitidine | DNA hypomethylating agent (decrease the amount of cellular DNA methylation, allowing for tumor suppressor gene expression) |

| Duvelisib, linperlisib, tenalisib | Oral dual inhibitor of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)-δ and/or PI3K-γ isoforms |

| Tazemetostat, valemetostat, tulmimetostat, HH2853 | Small molecules inhibiting histone methyltransferase activity of EZH1/2 (dual inhibitors) or EZH2 alone |

| Ruxolitinib, golidocitinib | Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors interfering with dysregulated cytokine signaling |

| Crizotinib, alectinib | Oral small-molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitor with binding specificity for ALK and ROS1 |

| Soquelitinib (CPI-818) | Oral small-molecule irreversible inhibitor of interleukin-2 inducible T-cell kinase (ITK) disrupting T-cell receptor signaling through ITK-mediated signal transduction |

Novel agents as frontline treatment

CHOP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone)-based chemotherapy regimens remain the standard frontline treatment of PTCL for curative intent in medically fit patients. Nevertheless, results remain unsatisfactory, with registry studies demonstrating a 5-year overall survival (OS) of 35%.3 Therefore, many efforts have been made to improve on this regimen.

Numerous phase 2 studies have investigated novel agents in the frontline setting (Table 2). The addition of agents active in T-cell lymphoma to CHOP, such as alemtuzumab, romidepsin, or pralatrexate, has often lead to increased toxicity without meaningful improvement in outcomes.4-6 Nevertheless, in a pooled analysis of prospective studies, the addition of etoposide (CHOEP) improved complete remission rate and event-free survival in patients ≤60 years of age, with the greatest benefit seen in patients with anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK)-positive ALCL.3

Selected trials that investigated novel additions added to CHOP backbone for frontline treatment of PTCL

| Treatment regimen . | Phase . | # evaluable patients . | ORR . | PFS . | OS . | Toxicities . | Reference . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Romidepsin + CHOP | 3 | 211 | 63% | Median 12 mo | Median 51.8 mo | G ≥ 3 thrombocytopenia 50%, neutropenia 49%, anemia 47% | 5 |

| BV-CHP | 3 | 226 | 83% | 5 yr 51% | 5 yr 70.1% | G ≥ 3 neuropathy 4% | 7 |

| Pralatrexate-CEOP | 2 | 33 | 70% | 2 yr 39% | 2 yr 60% | G ≥ 3 mucositis 18% | 34 |

| CHOEP Lenalidomide | 1 | 39 | 69% | 2 yr 55% | 2 yr 78% | G ≥ 3 febrile neutropenia 35% | 35 |

| CHOP + vorinostat | 1 | 12 | 93% | 2 yr 79% | 2 yr 81% | MTD 300 mg daily, diarrhea 63% | 36 |

| CHOP + oral azacitidine (CC-486) | 2 | 20 | (75% CR) | 2 yr 65.8% | 2 yr 68.4% | G ≥ 3 neutropenia 71% | 9 |

| CHOP + pralatrexate | 1 | 50 | 86% | NR | NR | 67% G ≥ 3 TEAEs, most commonly anemia (21%) | 6 |

| Treatment regimen . | Phase . | # evaluable patients . | ORR . | PFS . | OS . | Toxicities . | Reference . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Romidepsin + CHOP | 3 | 211 | 63% | Median 12 mo | Median 51.8 mo | G ≥ 3 thrombocytopenia 50%, neutropenia 49%, anemia 47% | 5 |

| BV-CHP | 3 | 226 | 83% | 5 yr 51% | 5 yr 70.1% | G ≥ 3 neuropathy 4% | 7 |

| Pralatrexate-CEOP | 2 | 33 | 70% | 2 yr 39% | 2 yr 60% | G ≥ 3 mucositis 18% | 34 |

| CHOEP Lenalidomide | 1 | 39 | 69% | 2 yr 55% | 2 yr 78% | G ≥ 3 febrile neutropenia 35% | 35 |

| CHOP + vorinostat | 1 | 12 | 93% | 2 yr 79% | 2 yr 81% | MTD 300 mg daily, diarrhea 63% | 36 |

| CHOP + oral azacitidine (CC-486) | 2 | 20 | (75% CR) | 2 yr 65.8% | 2 yr 68.4% | G ≥ 3 neutropenia 71% | 9 |

| CHOP + pralatrexate | 1 | 50 | 86% | NR | NR | 67% G ≥ 3 TEAEs, most commonly anemia (21%) | 6 |

Mo, months; MTD, maximum tolerated dose; NR, not reported; yr, year.

In the pivotal phase 3 ECHELON-2 study, brentuximab vedotin in combination with cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, and prednisone (BV-CHP) was compared with CHOP in PTCL with >10% CD30 expression. The study showed that BV-CHP was superior to CHOP, with improved PFS (5-year 51.4% vs 43.0%) and OS (5-year 70.1% vs 61.0%) without significantly increased toxicity.7 As a result, BV was approved in combination with chemotherapy for previously untreated PTCL and proved biomarker-driven approaches can improve outcomes in PTCL. Importantly, while the regulatory approval allows for the use of BV-CHP regardless of CD30 expression, use of BV-CHP in those with ≤10% CD30 expression remains controversial. Moreover, in ECHELON-2, the impact of BV-CHP was largely driven by the 70% of patients with ALCL, which uniformly expresses CD30 and is most sensitive to BV. While the study was not powered to compare efficacy between individual histologic subtypes, the benefit of BV-CHP was unclear in PTCL-NOS and angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma (AITL), in which CD30 expression is not uniform. Thus, BV-CHP is clearly the standard of care in ALCL, but CHOP remains a standard treatment option for other subtypes. This has prompted interest in other BV-containing frontline combinations in non-ALCL populations. In a phase 2 study of CD30-expressing PTCL (CD30 expression ≥1%), BV-CHP with the addition of etoposide (BV-CHEP) with maintenance BV (with or without consolidative autologous stem cell transplantation) was tolerable and effective, with objective response rate (ORR) upwards of 90% regardless of subtype or CD30 expression.8

The recent phase 3 study of CHOP versus CHOP with romidepsin, a histone deacetylase inhibitor (HDACi), underscores the importance of understanding subtype-specific activity in PTCL. The addition of romidepsin to CHOP did not improve outcomes in terms of response rates, progression-free survival (PFS), or OS, and it significantly increased toxicity, leading to decreased dose intensity of CHOP.5 However, subgroup analysis demonstrated a significantly improved PFS in TFH lymphomas compared with CHOP, with a median of 19.5 months versus 10.6 months (hazard ratio [HR] 0.70, CI 0.50–0.99). Overall, this study recapitulates that HDACi-based therapies are of interest in TFH lymphomas.

Smaller phase 1/2 studies have attempted to add novel agents to the CHOP backbone for untreated CD30-negative PTCL (Table 2), but these are not part of standard practice. For example, oral azacitidine given with CHOP demonstrated a 75% complete response (CR) with a high proportion of response in TFH lymphomas.9 These efforts have led to a US intergroup study to evaluate the incorporation of oral azacitidine or duvelisib to CHOP-based therapy (NCT04803201). Ongoing studies to incorporate novel agents into frontline therapy hope to improve on CHOP-based therapy for PTCL (Table 3).

Ongoing studies investigating novel agents in the frontline setting

| Treatment . | Trial . | Phase . | Patients . |

|---|---|---|---|

| BV-CHEP induction followed by BV consolidation | NCT03113500 | 2 | CD30-positive PTCL (≥1% expression) |

| CHOEP +/- duvelisib or oral azacitidine | NCT04803201 (ALLIANCE A051902) | 2 (randomized) | PTCL with ≤10% CD30 expression |

| Golidocitinib + CHOP | NCT05963347 | 2 | PTCL (including sALCL) |

| CHOP followed by selinexor maintenance | NCT05822050 | 2 | PTCL with CR on interim response assessment |

| CHOP +/- intravenous azacitidine and chidamide | NCT05678933 | 3 (randomized) | PTCL-TFH |

| Duvelisib + chidamide | NCT05976997 | 2 | PTCL-TFH |

| CHOP + parsaclisib | NCT05238064 | 1/2 | PTCL |

| CHOP +/- belinostat, COP + pralatrexate | NCT06072131 | 3 | PTCL |

| Azacitidine + chidamide | NCT04480125 | 2 | PTCL unfit for conventional chemotherapy |

| CHOP +/- selinexor with intravenous azacitidine OR duvelisib with intravenous azacitidine OR chidamide with tislelizumab (based on genotype) | NCT05675813 | 1/2 | PTCL |

| Treatment . | Trial . | Phase . | Patients . |

|---|---|---|---|

| BV-CHEP induction followed by BV consolidation | NCT03113500 | 2 | CD30-positive PTCL (≥1% expression) |

| CHOEP +/- duvelisib or oral azacitidine | NCT04803201 (ALLIANCE A051902) | 2 (randomized) | PTCL with ≤10% CD30 expression |

| Golidocitinib + CHOP | NCT05963347 | 2 | PTCL (including sALCL) |

| CHOP followed by selinexor maintenance | NCT05822050 | 2 | PTCL with CR on interim response assessment |

| CHOP +/- intravenous azacitidine and chidamide | NCT05678933 | 3 (randomized) | PTCL-TFH |

| Duvelisib + chidamide | NCT05976997 | 2 | PTCL-TFH |

| CHOP + parsaclisib | NCT05238064 | 1/2 | PTCL |

| CHOP +/- belinostat, COP + pralatrexate | NCT06072131 | 3 | PTCL |

| Azacitidine + chidamide | NCT04480125 | 2 | PTCL unfit for conventional chemotherapy |

| CHOP +/- selinexor with intravenous azacitidine OR duvelisib with intravenous azacitidine OR chidamide with tislelizumab (based on genotype) | NCT05675813 | 1/2 | PTCL |

sALCL, systemic ALCL.

CLINICAL CASE (continued)

The patient completes 6 cycles of CHOEP and has a complete metabolic response on imaging. Twelve months later, he presents with new axillary lymphadenopathy. PET/CT scan reveals FDG-avid bilateral axillary and retroperitoneal lymphadenopathy. Core needle biopsy of a left axillary lymph node confirms recurrent nodal TFH lymphoma, angioimmunoblastic subtype with 10% CD30 expression.

Novel agents in the relapsed/refractory setting

Relapsed/refractory PTCL has a poor prognosis, with a median OS of 9 months, as current therapy has limited response rate and durability.10 Therapies that have been approved by the Food and Drug Administration in this setting include romidepsin, belinostat, pralatrexate, brentuximab, and crizotinib (Table 4). Currently, excluding ALCL, there remains no standard therapy for relapsed/refractory PTCL. Allogeneic transplantation can be curative in up to 50% of cases10; however, this is not an option for many patients given difficulty in attaining disease control, donor availability, age, or comorbidities. Some series have explored autologous transplant consolidation in this patient population. The role of transplant is discussed in an accompanying review by Dreger and Schmitz.

Summary of selected trials investigating novel agents for relapsed/refractory PTCL

| Agent(s) . | Study phase . | Trial . | Patient population . | # evaluable patients . | Efficacy: overall . | Efficacy: subgroups . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single agents | ||||||

| Romidepsin20,21 | 2 | NCT00426764 | R/R PTCL | 130 | ORR 25% CR/CRu 15% mDOR 17 mo mPFS 4 mo | AITL (n = 27): ORR 30%, CR/CRu 19% PTCL-NOS (n = 69): ORR 29%, CR/CRu 14% ALK- ALCL (n = 21): ORR 24%, CR 19% |

| Belinostat23 | 2 | BELIEF (CLN-19) | R/R PTCL | 129 | ORR 26% CR 11% mDOR 13.6 mo mPFS 1.6 mo, mOS 7.9 mo | AITL (n = 10): ORR 45% PTCL-NOS (n = 18): ORR 23% ALK- ALCL (n = 13): ORR 15% |

| Azacitidine*25 | 3 | ORACLE (NCT03593018) | R/R AITL or nodal TFH lymphoma | 86 | 3-mo ORR 33% 3-mo CR 12% mPFS 5.6 mo mOS 18.4 mo | N/A |

| Valemetostat*30 | 2 | VALENTINE-PTCL01 (NCT04703192) | R/R PTCL (including ALCL with prior BV exposure) | 133 | ORR 44% CR 14% mDOR 11.9 mo mPFS 5.5 mo mOS 17.0 mo | AITL (n = 42): ORR 55%, CR 19% PTCL-NOS (n = 41): ORR 32%, CR 10% PTCL-TFH (n = 8): ORR 50%, CR 12% |

| Brentuximab vedotin17 | 2 | NCT01421667 | R/R CD30+ PTCL excluding ALCL | 34 | ORR 41% CR 24% mDOR 7.6 mo mPFS 2.6 mo | AITL (n = 13): ORR 54%, CR 38% PTCL-NOS (n = 21): ORR 33%, CR 14% |

| Crizotinib18 | 2 | NCT02419287 | R/R ALK+ ALCL | 12 | ORR 83% CR 58% mDOT 16.5 mo mPFS NR mOS NR | N/A |

| Duvelisib*26 | 2 | PRIMO (NCT03372057) | R/R PTCL | 101 | ORR 49% CR 34% mPFS 3.6 mo | AITL (n = 30): ORR 67%, CR 53% PTCL-NOS (n = 52): ORR 48%, CR 27% ALCL (n = 15): ORR 13%, CR 13% |

| Pralatrexate12 | 2 | PROPEL (NCT00364923) | R/R PTCL | 109 | ORR 29% CR/CRu 18% mDOR 10.1 mo mPFS 3.5 mo mOS 14.5 mo | AITL (n = 13): ORR 8% PTCL-NOS (n = 59): ORR 32% ALCL (n = 17): ORR 35% |

| Golidocitinib*29 | 2 | JACKPOT8 (NCT04105010) | R/R PTCL | 88 | ORR 44% CR 24% mDOR 20.7 mo mPFS 5.6 mo mOS 19.4 mo | AITL (n = 16): ORR 56% PTCL-NOS (n = 46): ORR 46% ALCL (n = 10): ORR 10% |

| Combination therapies | ||||||

| Romidepsin + pralatrexate*37 | 1 | NCT01947140 | R/R lymphoma | 23 | ORR 57% CR 17% mPFS 3.7 mo mOS 13.8 mo | TCL (n = 14): ORR 71% mDOR 4.29 mo mPFS 4.4 mo mOS 12.4 mo |

| Romidepsin + duvelisib*38 | 1b/2 | NCT02783625 | R/R PTCL | 48 | ORR 56% CR 44% mDOR 12 mo mOS 12 mo | AITL (n = 12): ORR 71% PTCL-NOS (n = 8): ORR 47% ALCL (n = 3): ORR 100% |

| Romidepsin + azacitidine*39 | 2 | NCT01998035 | Treatment-naïve or R/R PTCL | 23 | ORR 61% CR 48% mDOR 20.3 mo mPFS 8 mo mOS NR | R/R PTCL (n = 13): ORR 70%, CR 50% mDOR 13.5 mo mPFS 8 mo mOS 20.6 mo TFH (n = 15) ORR 80%, CR 60% mPFS 8.9 mo mOS NR |

| Romidepsin + lenalidomide*40 | 1b/2 | NCT01755975 | R/R NHL or HL | 45 | ORR 49% CR 18% mDOR 15.7 mo mPFS 5.7 mo mOS 24 mo | R/R PTCL (n = 15) ORR 53% CR 13% PTCL-NOS (n = 5) ORR 40% ATLL (n = 6): ORR 50% AITL (n = 2): ORR 100% |

| Romidepsin + lenalidomide + carfilzomib*40 | 1b/2 | NCT02341014 | R/R NHL or HL | 27 | ORR 48% CR 20% mDOR 10.6 mo mPFS 3.4 mo mOS 26.5 mo | R/R PTCL (n = 13) ORR 54% CR 39% PTCL-NOS (n = 7): ORR 29% AITL (n = 5): ORR 100% |

| Agent(s) . | Study phase . | Trial . | Patient population . | # evaluable patients . | Efficacy: overall . | Efficacy: subgroups . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single agents | ||||||

| Romidepsin20,21 | 2 | NCT00426764 | R/R PTCL | 130 | ORR 25% CR/CRu 15% mDOR 17 mo mPFS 4 mo | AITL (n = 27): ORR 30%, CR/CRu 19% PTCL-NOS (n = 69): ORR 29%, CR/CRu 14% ALK- ALCL (n = 21): ORR 24%, CR 19% |

| Belinostat23 | 2 | BELIEF (CLN-19) | R/R PTCL | 129 | ORR 26% CR 11% mDOR 13.6 mo mPFS 1.6 mo, mOS 7.9 mo | AITL (n = 10): ORR 45% PTCL-NOS (n = 18): ORR 23% ALK- ALCL (n = 13): ORR 15% |

| Azacitidine*25 | 3 | ORACLE (NCT03593018) | R/R AITL or nodal TFH lymphoma | 86 | 3-mo ORR 33% 3-mo CR 12% mPFS 5.6 mo mOS 18.4 mo | N/A |

| Valemetostat*30 | 2 | VALENTINE-PTCL01 (NCT04703192) | R/R PTCL (including ALCL with prior BV exposure) | 133 | ORR 44% CR 14% mDOR 11.9 mo mPFS 5.5 mo mOS 17.0 mo | AITL (n = 42): ORR 55%, CR 19% PTCL-NOS (n = 41): ORR 32%, CR 10% PTCL-TFH (n = 8): ORR 50%, CR 12% |

| Brentuximab vedotin17 | 2 | NCT01421667 | R/R CD30+ PTCL excluding ALCL | 34 | ORR 41% CR 24% mDOR 7.6 mo mPFS 2.6 mo | AITL (n = 13): ORR 54%, CR 38% PTCL-NOS (n = 21): ORR 33%, CR 14% |

| Crizotinib18 | 2 | NCT02419287 | R/R ALK+ ALCL | 12 | ORR 83% CR 58% mDOT 16.5 mo mPFS NR mOS NR | N/A |

| Duvelisib*26 | 2 | PRIMO (NCT03372057) | R/R PTCL | 101 | ORR 49% CR 34% mPFS 3.6 mo | AITL (n = 30): ORR 67%, CR 53% PTCL-NOS (n = 52): ORR 48%, CR 27% ALCL (n = 15): ORR 13%, CR 13% |

| Pralatrexate12 | 2 | PROPEL (NCT00364923) | R/R PTCL | 109 | ORR 29% CR/CRu 18% mDOR 10.1 mo mPFS 3.5 mo mOS 14.5 mo | AITL (n = 13): ORR 8% PTCL-NOS (n = 59): ORR 32% ALCL (n = 17): ORR 35% |

| Golidocitinib*29 | 2 | JACKPOT8 (NCT04105010) | R/R PTCL | 88 | ORR 44% CR 24% mDOR 20.7 mo mPFS 5.6 mo mOS 19.4 mo | AITL (n = 16): ORR 56% PTCL-NOS (n = 46): ORR 46% ALCL (n = 10): ORR 10% |

| Combination therapies | ||||||

| Romidepsin + pralatrexate*37 | 1 | NCT01947140 | R/R lymphoma | 23 | ORR 57% CR 17% mPFS 3.7 mo mOS 13.8 mo | TCL (n = 14): ORR 71% mDOR 4.29 mo mPFS 4.4 mo mOS 12.4 mo |

| Romidepsin + duvelisib*38 | 1b/2 | NCT02783625 | R/R PTCL | 48 | ORR 56% CR 44% mDOR 12 mo mOS 12 mo | AITL (n = 12): ORR 71% PTCL-NOS (n = 8): ORR 47% ALCL (n = 3): ORR 100% |

| Romidepsin + azacitidine*39 | 2 | NCT01998035 | Treatment-naïve or R/R PTCL | 23 | ORR 61% CR 48% mDOR 20.3 mo mPFS 8 mo mOS NR | R/R PTCL (n = 13): ORR 70%, CR 50% mDOR 13.5 mo mPFS 8 mo mOS 20.6 mo TFH (n = 15) ORR 80%, CR 60% mPFS 8.9 mo mOS NR |

| Romidepsin + lenalidomide*40 | 1b/2 | NCT01755975 | R/R NHL or HL | 45 | ORR 49% CR 18% mDOR 15.7 mo mPFS 5.7 mo mOS 24 mo | R/R PTCL (n = 15) ORR 53% CR 13% PTCL-NOS (n = 5) ORR 40% ATLL (n = 6): ORR 50% AITL (n = 2): ORR 100% |

| Romidepsin + lenalidomide + carfilzomib*40 | 1b/2 | NCT02341014 | R/R NHL or HL | 27 | ORR 48% CR 20% mDOR 10.6 mo mPFS 3.4 mo mOS 26.5 mo | R/R PTCL (n = 13) ORR 54% CR 39% PTCL-NOS (n = 7): ORR 29% AITL (n = 5): ORR 100% |

Not currently approved by the Food and Drug Administration for treatment of PTCL.

CRu, complete response unconfirmed; HL, Hodgkin lymphoma; mo, months; mOS, median OS; mPFS, median PFS; N/A, not available; NHL, non-Hodgkin lymphoma; R/R, relapsed/refractory.

Note: No head-to-head studies have been conducted, and thus direct comparisons cannot be made between these agents.

Chemotherapeutic options

Single-agent options are used standardly in relapsed/refractory PTCL and show benefit over combination chemotherapy in registry studies.11 Pralatrexate, an antifolate analogue, carries an ORR of 29% with a median PFS and OS of 3.5 and 14.5 months, respectively. The original study used dosing at 30 mg/m2 weekly for 6 weeks of a 7-week cycle, though with high rates of rash, cytopenias, and mucositis.12 Toxicities can be mitigated by dosing for 3 weeks of a 4-week cycle and leucovorin.13 While the study was not powered to investigate specific histologies, patients with AITL had lower response rates (8%). Other single-agent chemotherapies used for relapsed/refractory PTCL include gemcitabine and bendamustine. Similarly, combination chemotherapies commonly used in relapsed/refractory aggressive lymphomas, including etoposide, methylprednisolone, high-dose cytarabine, and cisplatin (ESHAP), ifosfamide, carboplatin, etoposide (ICE), and gemcitabine, dexamethasone, and cisplatin (GDP), can also be considered but have limited duration of response.14-16

CD30-directed therapy

Prior to its approval for frontline therapy, BV was studied in relapsed/refractory ALCL and later in relapsed/refractory CD30-positive PTCL. In AITL and PTCL-NOS, the ORR was 54% and 33%, with a limited median duration of response (mDOR) of 6.7 and 1.6 months, respectively. Importantly, responses were seen among patients with limited to undetectable CD30 expression.17 Furthermore, other CD30-directed therapies, both CAR T cells and bispecific antibodies, are currently under investigation.

ALK inhibitors

For patients with relapsed/refractory ALK-positive ALCL, ALK inhibitors remain another standard option. In 2021, crizotinib was approved for relapsed/refractory systemic ALCL based on a Children's Oncology Group trial. Of 26 patients with ALK- positive ALCL, ORR with crizotinib was 88% (CR, 81%) with responses lasting ≥12 months in 22% of patients.18 The second-generation ALK inhibitor alectinib has also demonstrated activity in relapsed/refractory ALK-positive ALCL and can be used as an alternative to crizotinib, especially in patients with central nervous system involvement.19

Histone deacetylase inhibitors and hypomethylating agents

Epigenetic modifying agents, such as HDACi and hypomethylating agents, have been of considerable interest in PTCL, as up to 75% of patients have mutations in genes involved in chromatin modification, with TFH lymphomas further enriched for recurrent mutations in TET2, RHOA, DNMT3A, and IDH2.2

Romidepsin was the first HDACi to show efficacy in relapsed/refractory PTCL. A single-arm international phase 2 study demonstrated that romidepsin had an ORR of 25% (CR, 15%) and a median DOR of 28 months.20 Further analysis showed that in the AITL subset (n = 27), ORR was 33% with median DOR not reached.21 A subsequent retrospective study and romidepsin- based phase 1/2 studies demonstrate that romidepsin-based therapy carries a higher ORR in patients with the TFH phenotype compared with patients with the non-TFH phenotype.22 Despite its demonstrated efficacy, romidepsin was voluntarily withdrawn by the manufacturer in 2021, but it still remains available given approval for CTCL and continued listing on the National Comprehensive Cancer Network compendium.

Another HDACi, belinostat, was approved based on a single-arm phase 2 study demonstrating an ORR of 25.8% (CR, 10.8%) with a median DOR of 13.6 months.23 Median PFS and OS were only 1.6 and 7.9 months, respectively. Again, responses in AITL were numerically higher compared with PTCL-NOS (45% vs 23%), underscoring the propensity of HDACi in TFH lymphomas. Similarly, chidamide, an oral selective class I HDACi, has demonstrated efficacy in a phase 2 multicenter study, with higher responses again seen in patients with AITL. Based on the results of this study, it was approved for use in China, and studies in other countries remain ongoing.24

Hypomethylating agents had shown significant activity in TFH lymphomas in early clinical series. As a result, oral azacitidine was studied in a phase 3 trial against investigator's choice therapy (bendamustine, gemcitabine, or romidepsin) for patients with relapsed/refractory TFH lymphomas. While ORR was lower in the azacitidine arm (33.3% vs 43.3%), azacitidine led to improved PFS (5.6 vs 2.8 months, p = 0.042) and OS (18.4 vs 10.3 months) compared with the control arm.25 While the study failed to meet its primary endpoint, azacitidine-based therapy remains intriguing.

CLINICAL CASE (continued)

The patient is started on treatment with BV and initially has a partial remission by PET/CT. Two months later, PET/CT reveals new FDG-avid bulky lymphadenopathy within the retroperitoneum. He is eager to discuss further options for treatment, including clinical trials.

Other novel agents for PTCL and future directions

Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase inhibitors

Multiple phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) inhibitors have been studied in PTCL. Duvelisib, an oral δ-γ PI3K inhibitor, was studied as a single agent and in combination, with significant activity. In the PRIMO study, duvelisib showed an ORR of 49% (CR, 34%) with a median PFS of 3.6 months. Although the study was not powered for subgroup analyses, duvelisib appeared to demonstrate preferential activity in certain subgroups (ORR of 67% in AITL and 48% in PTCL-NOS compared with 13% in ALCL). Patients with AITL and PTCL-NOS also had a significantly longer median PFS of 9.1 months and 3.5 months, respectively, compared with 1.5 months for ALCL.26 Based on these data, treatment with duvelisib can now be considered, especially for TFH lymphomas, but it carries a risk of transaminitis, colitis, rash, and infection. Duvelisib-based combinations are also being explored in the frontline setting (Table 2). Linperlisib, a PI3K-γ selective agent, has been studied in China, demonstrating a 48% ORR in relapsed/refractory PTCL with a relatively lower rate of diarrhea (14%) and transaminitis (20% to 23%); studies outside of China are ongoing.27 Given the relatively high ORR and CR rates, PI3K inhibitors are promising in PTCL, where there are limited other effective therapies.

JAK/STAT inhibitors

Preclinical data show Janus kinase (Jak/STAT pathway) activation may mediate the pathogenesis of PTCL, making it a promising target. Ruxolitinib, a JAK1/2 inhibitor, was investigated in patients with both relapsed/refractory PTCL and CTCL in a phase 2 study. Biomarker-driven cohorts were established based on the presence of activating mutations in the Jak/STAT pathway or overexpression of pSTAT3 by immunohistochemistry. Among 45 patients with PTCL, ORR was 37% and 36% in patients with Jak/STAT-activating mutations or pSTAT3 overexpression, respectively, compared with only 7% in patients without Jak/STAT activation.28 Similarly, golidocitinib, a JAK1 inhibitor, has been investigated in a phase 2 study in relapsed/refractory PTCL (n = 88), with an ORR of 44.3% (CR, 20.5%) and a median DOR of 20.7 months. Selectivity of golidocitinib for Jak/STAT-activated PTCL is unknown. The median PFS and OS were 5.6 months and 19.4 months, respectively. ORR in AITL was numerically higher at 56.3%. Around 55% of patients had a grade ≥3 treatment-related adverse event, the majority being hematologic.29 Given its tolerability and efficacy, golidocitinib is an encouraging, well- tolerated potential agent in PTCL.

EZH2 inhibitors

EZH inhibitors, small molecules inhibiting histone methyltransferase activity of EZH1 or EZH2, are promising in PTCL. Multiple EZH2 inhibitors have shown activity in PTCL, including valemetostat, tulmimetostat, and HH2853. In an international phase 2 single-arm study in relapsed/refractory PTCL, ORR for valemetostat was 43.7% (CR, 14.3%) with a median DOR of 11.9 months. Responses were highest in AITL at 54.8% followed by 31.7% in PTCL-NOS.30 Valemetostat was tolerable with 58% grade ≥3 adverse events, which were predominantly hematologic. Similarly, other EZH2 inhibitors (NCT04390737, NCT04104776) have shown activity and tolerability in PTCL. Given the efficacy and safety profile, EZH2 inhibitors are promising both as single agents and in combination but are not currently approved for standard use outside of Japan, where valemetostat was recently approved.

ITK inhibitors

Interleukin-2-inducible kinase (ITK) is an important mediator for T-cell receptor signaling. Studies have shown upregulation or aberrant activation of ITK in AITL and other nodal TFH lymphomas. One ITK inhibitor, soquelitinib, demonstrated tumor responses in heavily pretreated PTCLs in a phase 1/1b clinical trial, with a phase 3 study in development.31

Immune checkpoint inhibitors

While immune checkpoint inhibitors carry efficacy in other lymphomas, including cutaneous T-cell lymphoma and NK/T-cell lymphoma, they are not part of standard treatment in relapsed/refractory PTCL. Multiple studies incorporating immune checkpoint inhibitors in PTCL have shown incidences of hyperprogression (defined as progression within 1 cycle). In studies of single-agent nivolumab (n = 12) and pembrolizumab (n = 13), ORR has been 33%.32,33

Combinations of novel agents

While novel agents have primarily been studied as monotherapy, numerous studies have evaluated combinations of novel agents or the addition of novel agents to chemotherapy. Certain romidepsin-based combinations have demonstrated efficacy in TFH lymphomas (Table 4). Thus, combination of novel agents may be an important treatment paradigm in the future.

Conclusions

The treatment landscape for PTCLs has begun to shift with the introduction of novel agents. While initially studied in the relapsed/refractory settings, some novel agents are now being studied in frontline regimens. Many novel agents aim to capitalize on biologic differences between PTCL subtypes, including ALCL and TFH lymphomas. This deeper understanding of the biology of PTCL will continue to lead to further advances in the field, as therapy involving checkpoint inhibitors, bispecific antibodies, CAR T-cell therapies, and novel monoclonal antibodies continue to be developed. Despite these advances, for most patients, outcomes remain poor, and patient enrollment in clinical trials is paramount.

Acknowledgment

Neha Mehta-Shah is funded as a Scholar in Clinical Research through the Leukemia Lymphoma Society.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure

Imran A. Nizamuddin has no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Neha Mehta-Shah has served as a consultant for Kyowa Hakko, Daiichi Sankyo/UCB Japan, Secura Bio, AstraZeneca, Genentech/ Roche, and Janssen Oncology and has institutional research funding from Bristol Myers Squibb, Genentech/Roche, Celgene, Verastem, Innate Pharma, Corvus Pharmaceuticals, AstraZeneca, C4 Therapeutics, Daiichi Sankyo, Yingli Pharma, Dizal Pharma, Secura Bio, and MorphoSys.

Off-label drug use

Imran A. Nizamuddin: lenalidomide, azacitadine, duvelisib, valemetostat, golidocitinib and ruxolitinib.

Neha Mehta-Shah: lenalidomide, azacitadine, duvelisib, valemetostat, golidocitinib and ruxolitinib.