Abstract

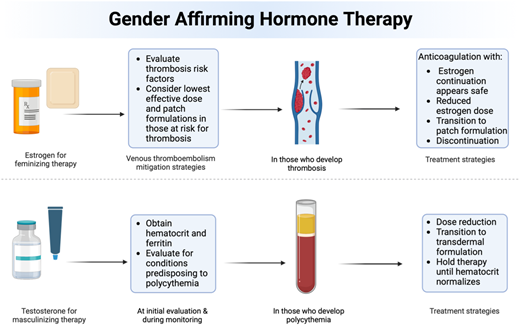

Research regarding the hematologic sequelae of estrogen and testosterone therapy for transgender people is an emerging area. While estrogen therapy has been widely studied in cisgender women, studies in transgender individuals are limited, revealing variable adverse effects influenced by the dose and formulation of estrogen used. Thrombotic risk factors in transgender and gender-diverse individuals are multifactorial, involving both modifiable and nonmodifiable factors. Management of venous thromboembolism (VTE) in individuals receiving gender-affirming estrogen entails standard anticoagulation therapy alongside shared decision-making regarding hormone continuation and risk factor modification. While data and guidance from cisgender women can offer a reference for managing thrombotic risk in transgender individuals on hormone therapy, fully applying these insights can be challenging. The benefits of gender-affirming hormone therapy include significantly reducing the risk of suicide and depression, highlighting the importance of a contemplative approach to the management of hormonal therapy after a VTE event. Although limited, the available data in the literature indicate a low thrombotic risk for transgender individuals undergoing gender-affirming testosterone therapy. However, polycythemia is a common adverse effect necessitating monitoring and, occasionally, adjustments to hormonal therapy. Additionally, iron deficiency may arise due to the physiological effects of testosterone or health care providers' use of phlebotomy, an aspect that remains unstudied in this population. In conclusion, while the set of clinical data is expanding, further research remains vital to refine management strategies and improve hematologic outcomes for transgender individuals undergoing gender-affirming hormone therapy.

Learning Objectives

Review the latest data concerning patients undergoing gender-affirming hormone therapy

Discuss strategies aimed at minimizing thrombotic risk, such as utilizing transdermal applications

Evaluate treatment options gleaned from studies involving cisgender individuals

Examine the incidence of polycythemia associated with testosterone use in gender-affirming hormone therapy, and explore treatment strategies including dose adjustment, transdermal formulations, and temporary interruptions in therapy

Introduction

Survey-based studies report that 0.3%-4.5% of the adult population self-identify as transgender or gender diverse, although obtaining accurate data poses methodological challenges.1 Some, but not all, transgender individuals choose to pursue gender-affirming care, which can include surgical procedures and/or gender-affirming hormone therapy (GAHT), ideally supported by a multidisciplinary care team. As a critical component of care, GAHT has proven to reduce levels of depression and suicidality while enhancing overall life satisfaction.2 In the field of classical hematology, it is important to understand the hematologic complications associated with GAHT and the development of effective treatment strategies for thrombotic complications.

Estrogen usage can lead to thrombotic complications in cisgender women, with the degree of risk varying depending on individual risk factors and the type and route of estrogen used. The data on thrombotic complications in individuals receiving estrogen for GAHT are limited but expanding, as outlined later in this manuscript; however, insights can be drawn from established findings in cisgender individuals. The use of exogenous estrogen has been shown to elevate the clinical risk of developing thrombosis and may alter the levels of some hemostatic proteins.3,4 For example, although limited, a 1-year follow-up study reported an increase in levels of factors IX and XII and diminished levels antithrombin and protein C in gender-diverse and transgender individuals receiving estrogen.5 In addition, as outlined later in this manuscript, studies have observed that the dosage and route of estrogen administration can influence thrombotic risk.6

The most prevalent adverse effect seen in individuals receiving testosterone for GAHT is polycythemia. Unfortunately, the risk of thrombosis and the implications of polycythemia in this population are poorly studied; thus, much is extrapolated from studies of cisgender men using testosterone supplementation. Given this, providers find difficulty in determining the appropriate treatment strategy when polycythemia develops. We aim to describe the currently available data, including what is known regarding cisgender individuals on hormone therapy, and present our approach to treating patients on GAHT who develop hematologic adverse effects.

CLINICAL CASE 1

A 30-year-old transgender individual with she/her/hers pronouns and a past medical history notable for type 2 diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia, hypertension, and gender-affirming estrogen use presents to the hematology clinic. She has a recent history of left femoral venous thrombosis after a 1-hour airplane flight. Following the diagnosis of her left femoral deep vein thrombosis, the patient started apixaban. Additionally, her oral estradiol dose, initially 2 mg daily, was reduced to 1 mg daily. She now presents to your clinic 8 weeks later to discuss increasing her estradiol dose and exploring alternate routes of administration. On physical exam, she is in no acute distress, facial hair is present, partial hair thinning is observed, the left lower extremity is unremarkable, and her vital signs are stable. Her body mass index (BMI) is 32. The patient denies smoking, alcohol use, or substance abuse. She lives at home with her partner and works as a first-grade elementary school teacher.

What is the current understanding of the risks of thrombosis in individuals receiving gender-affirming estrogen?

Oral and transdermal estrogen formulations are commonly used as GAHT, yet our understanding of the risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE) in this population remains limited. Several older retrospective studies have suggested that individuals undergoing estrogen-based GAHT have an increased risk of developing VTE.3,4,7-9 However, it is important to note that many of these studies were conducted over a decade ago and may provide outdated data regarding exogenous estrogen formulations. Ethinyl estradiol and some conjugated estrogens are no longer recommended in the setting of gender affirmation due to the increased risk of thrombosis associated with these formulations.10 Advances in transgender care and safer GAHT options mean that outdated studies in cisgender women may not accurately reflect the current VTE risk in transgender individuals (Table 1).

Updated retrospective and prospective studies transgender individuals receiving GAHT and risk of venous thrombosis

| Study . | Patient demographics . | Study type . | Results . | Interpretation . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Manchkanti et al (2023)25 | N = 12 369 transgender individuals | Retrospective observational | The transgender individuals receiving estrogen had a lower incidence of cerebral infarcts (0.21% vs. 0.42%, P = .0003) and a moderately decreased incidence of MI (0.14% vs 0.22%, P = .062) compared to cisgender women. | The study observed decreases in rates of thrombotic events, acute MI, and cerebral infarction in transgender individuals receiving estrogen compared to cisgender women. |

| Mullins et al (2021)48 | N = 611 | Retrospective observational | Among 611 participants, 28.8% were transgender individuals receiving estrogen and 68.1% were transgender individuals receiving testosterone. The median age was 17 years at GAHT initiation. 5 individuals were treated with anticoagulation during GAHT: 2 with a previous thrombosis and 3 for prophylaxis. No participant developed thrombosis while on GAHT. | The findings suggest that, in youth, GAHT titrated within physiologic range does not carry a significant risk of thrombosis in the short-term. |

| Kozato et al (2021)41 | N = 407 | Retrospective observational | 407 transgender individuals receiving estrogen undergoing primary vaginoplasty. Of all cases, 1 patient presented with VTE from the cohort whose estrogen was suspended prior to surgery. No VTE events were noted among those who continued. | Perioperative VTE was not a significant risk in a large, homogenously treated cohort of transgender individuals, independent of whether estrogen was suspended prior to surgery. |

| Scheres et al (2021)5 | N = 198 | Prospective observational | Transgender individuals on estrogen GAHT developed increased factors IX and XI as well as a decrease in protein C. | In transgender individuals receiving estrogen, GAHT resulted in procoagulant changes, which likely contributes to the observed increase in VTE risk. |

| Pyra et al (2020)15 | N = 4402 | Retrospective observational | 0.8% of transgender individuals receiving estrogen had a thrombotic event and 2.1% of transgender individuals receiving testosterone developed HTN. Among transgender individuals receiving estrogen, there was no association between thrombosis and GAHT as assessed by blood concentrations. | The AUthors found no association between GAHT and HTN or between GAHT and VTE. More research is needed to examine the effects of transgender individuals receiving estrogen. |

| Getahun et al (2018)6 | N = 102 417 | Retrospective observational | Transgender individuals receiving oral estrogen had a higher incidence of VTE, with 2- and 8-year risk differences of 4.1 (95% CI, 1.6-6.7) and 16.7 (CI, 6.4-27.5) per 1000 persons relative to cisgender men and cisgender women | Higher incidence of VTE and ischemic stroke were observed among transgender individuals receiving oral estrogen. |

| Arnold et al (2016)29 | N = 676 transgender individuals receiving estrogen | Retrospective observational | Transgender individuals receiving oral estradiol followed for 1.9 years. Only 1 individual, or 0.15% of the population, sustained a VTE, for an incidence of 7.8 events per 10 000 person-years. | There was a low incidence of VTE in this population of transgender individuals receiving oral estrogen. |

| Seal et al (2012)71 | N = 320 | Retrospective observational | Thromboembolism occurred in 1.2% of individuals, more frequently in those treated with CEE than in those treated with either estrogen valerate or ethinyl estradiol (4.4% vs. 0.6% vs. 0.7%, P = .026) | CEE is associated with a higher incidence of thromboembolism than treatment with other estrogen types. |

| Wierckx et al (2012)3 | N = 100 | Cross- sectional study | After being on hormone treatment for an average of 11.3 years, 6% of transgender individuals receiving estrogen experienced a thromboembolic event, and another 6% experienced other cardiovascular problems. | A number of transgender individuals receiving estrogen experience complications from GAHT, such as thromboembolic or other cardiovascular events, during hormone treatment, possibly related to older age, estrogen application, and lifestyle factors. |

| Ott et al (2010)30 | N = 251 | Retrospective observational | Activated protein C resistance was detected in 18/251 patients, and protein C deficiency was detected in 1 patient. None of the patients developed VTE GAHT. | VTE in GAHT is rare. General screening for thrombophilic defects in transgender individuals is not recommended. GAHT is feasible in individuals with APC resistance. |

| van Kesteren et al (1997)72 | N = 1109 | Retrospective observational | In both the transgender individuals receiving estrogen and transgender individuals receiving testosterone, total mortality was not higher than in the general population; the observed mortality could not be related to hormone treatment. | VTE was the major complication in transgender individuals treated with oral estrogens and antiandrogens, but fewer cases were observed since the introduction of transdermal estradiol in those over 40 years of age. |

| Study . | Patient demographics . | Study type . | Results . | Interpretation . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Manchkanti et al (2023)25 | N = 12 369 transgender individuals | Retrospective observational | The transgender individuals receiving estrogen had a lower incidence of cerebral infarcts (0.21% vs. 0.42%, P = .0003) and a moderately decreased incidence of MI (0.14% vs 0.22%, P = .062) compared to cisgender women. | The study observed decreases in rates of thrombotic events, acute MI, and cerebral infarction in transgender individuals receiving estrogen compared to cisgender women. |

| Mullins et al (2021)48 | N = 611 | Retrospective observational | Among 611 participants, 28.8% were transgender individuals receiving estrogen and 68.1% were transgender individuals receiving testosterone. The median age was 17 years at GAHT initiation. 5 individuals were treated with anticoagulation during GAHT: 2 with a previous thrombosis and 3 for prophylaxis. No participant developed thrombosis while on GAHT. | The findings suggest that, in youth, GAHT titrated within physiologic range does not carry a significant risk of thrombosis in the short-term. |

| Kozato et al (2021)41 | N = 407 | Retrospective observational | 407 transgender individuals receiving estrogen undergoing primary vaginoplasty. Of all cases, 1 patient presented with VTE from the cohort whose estrogen was suspended prior to surgery. No VTE events were noted among those who continued. | Perioperative VTE was not a significant risk in a large, homogenously treated cohort of transgender individuals, independent of whether estrogen was suspended prior to surgery. |

| Scheres et al (2021)5 | N = 198 | Prospective observational | Transgender individuals on estrogen GAHT developed increased factors IX and XI as well as a decrease in protein C. | In transgender individuals receiving estrogen, GAHT resulted in procoagulant changes, which likely contributes to the observed increase in VTE risk. |

| Pyra et al (2020)15 | N = 4402 | Retrospective observational | 0.8% of transgender individuals receiving estrogen had a thrombotic event and 2.1% of transgender individuals receiving testosterone developed HTN. Among transgender individuals receiving estrogen, there was no association between thrombosis and GAHT as assessed by blood concentrations. | The AUthors found no association between GAHT and HTN or between GAHT and VTE. More research is needed to examine the effects of transgender individuals receiving estrogen. |

| Getahun et al (2018)6 | N = 102 417 | Retrospective observational | Transgender individuals receiving oral estrogen had a higher incidence of VTE, with 2- and 8-year risk differences of 4.1 (95% CI, 1.6-6.7) and 16.7 (CI, 6.4-27.5) per 1000 persons relative to cisgender men and cisgender women | Higher incidence of VTE and ischemic stroke were observed among transgender individuals receiving oral estrogen. |

| Arnold et al (2016)29 | N = 676 transgender individuals receiving estrogen | Retrospective observational | Transgender individuals receiving oral estradiol followed for 1.9 years. Only 1 individual, or 0.15% of the population, sustained a VTE, for an incidence of 7.8 events per 10 000 person-years. | There was a low incidence of VTE in this population of transgender individuals receiving oral estrogen. |

| Seal et al (2012)71 | N = 320 | Retrospective observational | Thromboembolism occurred in 1.2% of individuals, more frequently in those treated with CEE than in those treated with either estrogen valerate or ethinyl estradiol (4.4% vs. 0.6% vs. 0.7%, P = .026) | CEE is associated with a higher incidence of thromboembolism than treatment with other estrogen types. |

| Wierckx et al (2012)3 | N = 100 | Cross- sectional study | After being on hormone treatment for an average of 11.3 years, 6% of transgender individuals receiving estrogen experienced a thromboembolic event, and another 6% experienced other cardiovascular problems. | A number of transgender individuals receiving estrogen experience complications from GAHT, such as thromboembolic or other cardiovascular events, during hormone treatment, possibly related to older age, estrogen application, and lifestyle factors. |

| Ott et al (2010)30 | N = 251 | Retrospective observational | Activated protein C resistance was detected in 18/251 patients, and protein C deficiency was detected in 1 patient. None of the patients developed VTE GAHT. | VTE in GAHT is rare. General screening for thrombophilic defects in transgender individuals is not recommended. GAHT is feasible in individuals with APC resistance. |

| van Kesteren et al (1997)72 | N = 1109 | Retrospective observational | In both the transgender individuals receiving estrogen and transgender individuals receiving testosterone, total mortality was not higher than in the general population; the observed mortality could not be related to hormone treatment. | VTE was the major complication in transgender individuals treated with oral estrogens and antiandrogens, but fewer cases were observed since the introduction of transdermal estradiol in those over 40 years of age. |

APC, argon plasma coagulation; CEE, conjugated equine estrogen; HTN, hypertension.

Although data on VTE risk in transgender women are less comprehensive, the majority of cohort and retrospective studies available report an increased VTE risk associated with oral estrogen formulations. A large cohort study found that the hazard ratio for VTE in transgender women receiving oral estrogen was 2.7 (95% CI, 1.2-6.1) compared to cisgender women, although this increased risk was not observed with transdermal estrogen.6 Despite the elevated relative risk, the actual incidence of VTE remains low. A meta-analysis of 11 542 transgender individuals on oral estrogen reported an absolute incidence of VTE at 2 per 1000 person-years (95% CI, per 1000 person-years).11 This highlights that, while the relative risk is higher, the overall occurrence of VTE in this population is relatively rare. The current literature does not provide enough evidence to justify prohibiting the use of oral estrogen in transgender individuals. Until more data become available, oral estrogen can be safely administered with careful monitoring and a thorough risk assessment before beginning therapy (Table 2).

Selected trials on hormone replacement therapy and risk of VTE in cisgender women

| Study . | Patient demographics . | Study type . | Results . | Interpretation . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weller et al (2023)73 | N = 20 359 | Case control study | For exposures within 60 days, oral HRT VTE risk was almost twice as high as transdermal HT (OR = 1.92; 95% CI, 1.43-2.60); transdermal HRT did not elevate risk compared with no exposure (unopposed OR = 0.70; 95% CI, 0.59-0.83; combined OR = 0.73; 95% CI, 0.56-0.96) | Transdermal HRT did not elevate risk. Oral HRT combinations with estradiol were lower risk than other forms of estrogen. Oral combined hormone contraceptives had much higher risk than oral combined hormonal HRT. |

| Olié et al (2010)19 | Meta-analysis | 2 large cohort studies confirmed that oral but not transdermal estrogens were associated with VTE risk among postmenopAUsal women. Pooled risk ratios for VTE were 1.9 (95% CI, 1.3-2.3) and 1.0 (95% CI 0.9-1.1), respectively. | Transdermal estrogens may substantially improve the benefit/risk ratio of postmenopAUsal hormone therapy and should be considered as a safer option, especially for women at high risk for VTE. | |

| Canonico et al (2007)9 | Meta-analysis | Compared with nonusers of estrogen, the OR for first-time VTE in current users of oral estrogen was 2.5 (95% CI, 1.9-3.4) and in current users of transdermal estrogen was 1.2 (95% CI, 0.9-1.7). | Oral estrogen increases the risk of VTE, especially during the first year of treatment. Transdermal estrogen may be safer with respect to thrombotic risk. | |

| Oger et al (2003)7 | N = 196 | Randomized control trial | Oral HRT induced an ETP-based APC resistance compared with both placebo (P = .006) and transdermal HRT (P < .001), but there was no significant effect of transdermal HRT compared with placebo (P = .191). | The data show that oral, unlike transdermal, estrogen induces APC resistance and activates blood coagulation. These results emphasize the importance of the route of estrogen administration. |

| Hoibraaten et al (2000)13 | N = 140 | Randomized double-blind, placebo-controlled trial | The primary outcome was recurrent DVT or PE. The study was terminated prematurely based on the results of circumstantial evidence emerging during the trial. 8 women in the HRT group and 1 woman in the placebo group developed VTE. The incidence of VTE was 10.7% in the HRT group and 2.3% in the placebo group. In the HRT group, all events happened within 261 days after inclusion. | These data strongly suggests that women who have previously suffered a VTE have an increased risk of recurrence on HRT. This treatment should therefore be avoided in this patient group if possible. |

| Grady et al (1998) (HERS study)74 | N = 2763 | Randomized clinical trial | During an average follow-up of 4.1 years, treatment with oral CEE plus medroxyprogesterone acetate did not reduce the overall rate of CHD events in postmenopausal women with established coronary disease. The treatment did increase the rate of thromboembolic events and gallbladder disease. | CEE plus medroxyprogesterone acetate did not confer a cardiovascular benefit. |

| Study . | Patient demographics . | Study type . | Results . | Interpretation . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weller et al (2023)73 | N = 20 359 | Case control study | For exposures within 60 days, oral HRT VTE risk was almost twice as high as transdermal HT (OR = 1.92; 95% CI, 1.43-2.60); transdermal HRT did not elevate risk compared with no exposure (unopposed OR = 0.70; 95% CI, 0.59-0.83; combined OR = 0.73; 95% CI, 0.56-0.96) | Transdermal HRT did not elevate risk. Oral HRT combinations with estradiol were lower risk than other forms of estrogen. Oral combined hormone contraceptives had much higher risk than oral combined hormonal HRT. |

| Olié et al (2010)19 | Meta-analysis | 2 large cohort studies confirmed that oral but not transdermal estrogens were associated with VTE risk among postmenopAUsal women. Pooled risk ratios for VTE were 1.9 (95% CI, 1.3-2.3) and 1.0 (95% CI 0.9-1.1), respectively. | Transdermal estrogens may substantially improve the benefit/risk ratio of postmenopAUsal hormone therapy and should be considered as a safer option, especially for women at high risk for VTE. | |

| Canonico et al (2007)9 | Meta-analysis | Compared with nonusers of estrogen, the OR for first-time VTE in current users of oral estrogen was 2.5 (95% CI, 1.9-3.4) and in current users of transdermal estrogen was 1.2 (95% CI, 0.9-1.7). | Oral estrogen increases the risk of VTE, especially during the first year of treatment. Transdermal estrogen may be safer with respect to thrombotic risk. | |

| Oger et al (2003)7 | N = 196 | Randomized control trial | Oral HRT induced an ETP-based APC resistance compared with both placebo (P = .006) and transdermal HRT (P < .001), but there was no significant effect of transdermal HRT compared with placebo (P = .191). | The data show that oral, unlike transdermal, estrogen induces APC resistance and activates blood coagulation. These results emphasize the importance of the route of estrogen administration. |

| Hoibraaten et al (2000)13 | N = 140 | Randomized double-blind, placebo-controlled trial | The primary outcome was recurrent DVT or PE. The study was terminated prematurely based on the results of circumstantial evidence emerging during the trial. 8 women in the HRT group and 1 woman in the placebo group developed VTE. The incidence of VTE was 10.7% in the HRT group and 2.3% in the placebo group. In the HRT group, all events happened within 261 days after inclusion. | These data strongly suggests that women who have previously suffered a VTE have an increased risk of recurrence on HRT. This treatment should therefore be avoided in this patient group if possible. |

| Grady et al (1998) (HERS study)74 | N = 2763 | Randomized clinical trial | During an average follow-up of 4.1 years, treatment with oral CEE plus medroxyprogesterone acetate did not reduce the overall rate of CHD events in postmenopausal women with established coronary disease. The treatment did increase the rate of thromboembolic events and gallbladder disease. | CEE plus medroxyprogesterone acetate did not confer a cardiovascular benefit. |

APC, argon plasma coagulation; ETP, endogenous thromobin potential; HT, hormone therapy.

As supported by data outlined in the following section, transdermal estrogen may be a safer option, potentially carrying minimal thrombotic risk for transgender individuals seeking GAHT. In addition, lower doses of hormonal therapy may be considered for high-risk patients to potentially decrease the risk of a VTE event, although high-quality data to support this recommendation are lacking. It is important to note that delaying or discontinuing estrogen therapy in transgender women seeking GAHT can deprive them of significant psychological benefits.

What can be extrapolated from data in cisgender women receiving exogenous estrogen?

Estrogen replacement therapy is used in some settings to alleviate postmenopAUsal symptoms in cisgender women, yet it poses certain risks. Therefore, estrogen replacement therapy has been extensively studied in numerous large-scale studies regarding its effects on cisgender women's health (Table 2). A comprehensive meta-analysis of 12 studies, encompassing the Women's Health Initiative publications and other high-quality studies, revealed that current oral hormone replacement therapy users experienced an elevated risk of VTE overall (relative risk [RR], 2.14; 95% CI, 1.64-2.81), with the highest incidence observed within the first year of use (RR, 3.49; 95% CI, 2.33-5.59). It's worth noting that the Women's Health Initiative study is ongoing and is slated to conclude in 2026.12 In addition, a recent study has indicated that cisgender women on hormone replacement therapy (HRT) have an annual risk of VTE recurrence of 10%.13

Observational studies suggest that oral estrogen elevates systemic levels of clotting factors II, VII, VIII, and X and fibrinogen, decreases the levels of antithrombin and protein S, and induces an acquired resistance to activated protein C in cisgender women.7,14 A recent study observed similar changes in procoagulant markers in transgender and gender diverse individuals receiving an oral estrogen formulation.5,15 A prospective study involving 200 participants tracked over 12 months found that transgender individuals receiving oral estrogen showed increased levels of clotting factors IX (9.6 IU/dL; 95% CI, 3.1-16.0 IU/dL) and XI (13.5 IU/dL; 95% CI, 9.5-17.5 IU/dL), alongside decreased levels of the anticoagulant protein C (−7.7 IU/dL; 95% CI, −10.1 to −5.2 IU/dL).5 These findings suggest that oral estrogen formulations may alter the coagulation profile in transgender and gender-diverse individuals. However, the study is limited by its 12-month follow-up period, thereby restricting the observation of potential long-term side effects associated with oral estrogen therapy beyond this timeframe.

The clinical risk of VTE associated with hormone replacement therapy appears to be multifactorial, influenced by factors such as formulation, dosage, personal risk factors, and a history of previous thrombotic events. Differences in how hormone therapy affects blood clotting mechanisms may explain the varying risks of VTE between oral and transdermal estrogen. Oral estrogen undergoes first-pass metabolism in the liver, which can disrupt the synthesis and clearance of proteins involved in blood clotting.16 This disruption can activate the blood clotting cascade, increasing fibrinolytic activity and thus increasing one's risk of thrombosis.17 In contrast, these effects were not observed among individuals taking transdermal estrogen.17

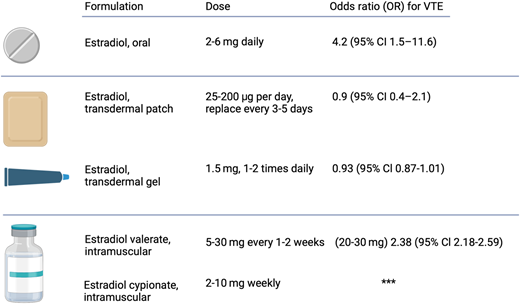

A long-term follow-up study found that transdermal estrogen appears to have lower VTE risks, leading some clinicians to recommend it as a first-line therapy, especially for patients over 40 years old.18 In addition, in a multicenter case-control study of thromboembolism among postmenopAUsal cisgender women aged 45-70 years, the odds ratio (OR) for VTE was 4.2 (95% CI, 1.5-11.6) in users of oral estrogen and 0.9 (95% CI, 0.4-2.1) in users of transdermal estrogen when each group was compared with nonusers.9 In addition, a comprehensive meta-analysis in cisgender women revealed that transdermal forms of estrogen may mitigate the risk of VTE compared to oral formulations. The data indicated VTE risks of 1.9 times (95% CI, 1.3-2.3) for users of oral estrogen compared to nonusers of estrogen and 1.0 times (95% CI, 0.9-1.1) for users of transdermal estrogen.9,19 These findings suggest that opting for transdermal estrogen over oral formulations may reduce the risk of VTE and its recurrence, offering a safer option for transgender and gender-diverse individuals undergoing GAHT who have risk factors for thrombosis.

Approaching the risk of thrombosis with gender-affirming estrogen therapy in specific situations

The lack of randomized controlled trials focusing on transgender individuals and GAHT makes it difficult to assess the risk of VTE. However, there are a few key points we can extrapolate from the already established data on managing thrombotic risk in cisgender and transgender individuals. First, an individual's risk of VTE is influenced by both their underlying medical predispositions and the specific dosage and administration pathway of the GAHT.

Modifiable risk factors

Body mass index

Higher BMI has been shown to be associated with an increased risk of VTE in cisgender individuals.11 The LITE study demonstrated a notable association between an individuals' BMI and the hazard ratios for VTE. Specifically, the AUthors found that individuals with a BMI over 35 kg/m2 had a hazard ratio of 3.09 (95% CI, 2.26-4.23), which is approximately twice the hazard ratio of those with a BMI between 25 and 30 kg/m2, whose hazard ratio is 1.58 (95% CI, 1.20-2.09).20 However, there is no high-quality data indicating that GAHT increases BMI in transgender individuals, nor is there evidence linking increased BMI to a higher risk of VTE in transgender and gender-diverse individuals. Future research should focus on the long-term implications of GAHT on BMI, body composition, and associated health outcomes.

Smoking

While several studies have explored the association between smoking and its effect on cardiovascular health, there are limited data linking smoking to increased VTE risk. In a large population-based case-control study of 3989 cisgender women, researchers evaluated smoking as a risk factor for VTE. They reported that current and former smokers had moderately increased risks for VTE compared to nonsmokers (current smokers' OR, 1.43 [95% Cl, 1.28-1.60]; former smokers' OR 1.23 [95% Cl, 1.09-1.38]).21 In addition, this study reported that cisgender women who did not use hormonal therapy but currently smoked had a 2.0-fold increased risk of VTE. Cisgender women who used oral contraceptives and did not smoke had a 3.9-fold increased risk. Individuals who both smoked and used oral contraceptives had an 8.8-fold higher risk of VTE (OR, 8.79; 95% CI, 5.73-13.49) compared to nonsmokers who did not use oral contraceptives.21

Smoking can lead to physiological changes that heighten the risk of cardiovascular disease. This includes boosting insulin resistance, increasing catecholamines that raise blood pressure and heart rate and elevating lipid levels such as total cholesterol, triglycerides, and low-density lipoprotein.22 These changes are reported in the literature to worsen overall cardiovascular health among cisgender men and cisgender women. There is a lack of robust literature analyzing the risk of VTE associated with smoking while on GAHT. There is a need for comprehensive studies to better understand the consequences of these combined risk factors.

Modifiable cardiovascular disease risk factors

Recent data indicate that cisgender individuals undergoing hormonal therapy face heightened cardiovascular health risks. A large, randomized controlled trial of hormone replacement therapy in postmenopAUsal women randomized participants to either 1 of 2 different hormonal replacement regimens or placebo and followed them for 12 months. Cisgender women had an increased risk of heart disease including unstable angina, fatal and nonfatal myocardial infarction (MI), and sudden coronary death. Secondary outcomes included an increased risk for deep vein thrombosis (DVT), pulmonary embolism (PE), and retinal vein occlusion.23 Likewise, the Women's Health Initiative study monitored 16 608 postmenopAUsal cisgender women aged 50-79 years with an intact uterus who were randomized to 1 of 2 arms, those receiving hormone replacement therapy or those receiving a placebo. The study reported that those receiving hormone replacement therapy had an increased risk of cardiovascular disease, nonfatal MI, PE, VTE, strokes, and various primary cancers. The estimated hazard ratios (95% CIs) were as follows: coronary heart disease (CHD), 1.29 (1.02-1.63) with 286 cases; stroke, 1.41 (1.07-1.85) with 212 cases; and PE, 2.13 (1.39-3.25) with 101 cases. Additionally, estrogen plus progestin therapy was associated with absolute excess risks per 10 000 person-years, including 7 more CHD events, 8 more strokes, 8 more PEs, and 8 or more invasive breast cancers.24 The study concluded that hormone replacement therapy should not be initiated or continued for the primary prevention of cardiovascular heart disease.24

Few prospective studies have evaluated GAHT and its effects on cardiovascular health in young transgender individuals. A nationwide database study of 12 369 patients reported that transgender individuals receiving estrogen therapy had a lower occurrence of cerebral infarcts (0.21% vs 0.42%, P = .0003) and a moderately decreased incidence of MI (0.14% vs 0.22%, P = .062) compared to cisgender women.25 However, the incidence of venous thrombosis was similar between transgender individuals and cisgender women.25 Additionally, a small prospective study of 12 transgender individuals, aged 17-33 years, showed a significant decrease in endothelin levels after 4 months of GAHT (8.1 ± 3.0 to 5.1 ± 2.0 ng/mL; P < .01), which is suggested to correlate with decreases in cardiovascular events.26 Conversely, a meta-analysis reported impaired lipid profiles in transgender on GAHT, including increased triglycerides (21.4 mg/dL; 95% CI, 0.14 to 42.6) at ≥ 24 months and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels at ≥ 24 months (17.8 mg/dL; 95% CI, 3.5 to 32.1).22

It is important to note that the existing literature primarily focuses on younger transgender individuals, which narrows the scope of understanding regarding GAHT's cardiovascular risks among older transgender adults. Additionally, the lack of prospective and randomized controlled trials on GAHT impedes comprehension of its relationship with cardiovascular disease and risk. Therefore, it's crucial to weigh the risks vs benefits of GAHT for each patient to determine the best course of action for maintaining optimal cardiovascular health during hormone therapy.

Nonmodifiable risk factors

Underlying thrombophilia and hypercoagulable blood disorders have been well documented to increase VTE events in cisgender women.8 While we do not recommend screening asymptomatic transgender and gender-diverse individuals for thrombophilia before starting GAHT, those with known thrombophilia, myeloproliferative neoplasm, or active malignancy should have a comprehensive discussion regarding the risks and benefits of using exogenous estrogen. The heightened risk of thrombosis associated with these conditions as well as the psychological impact of discontinuing GAHT should be considered.

A prior VTE is one of the most significant risk factors for predicting future recurrences. Following an initial treatment period of 3-6 months after a VTE event, individuals should undergo risk assessment for secondary VTE prevention either through anticoagulation therapy or observation.27 Without continued long-term anticoagulation, about 30% of patients experience VTE recurrence within the subsequent decade.20,27

Choice of GAHT

GAHT offers several recognized benefits in individuals seeking hormonal therapy, including evidence of decreasing suicidality and depression.2 However, certain estrogen formulations appear to be more prothrombotic than others. Ethinyl estradiol was widely used in the past; however, this practice has mostly ceased due to safety concerns around VTE risk. A large study documented a 45-fold increased risk of VTE (occurring in 6.3%) in transgender and gender-diverse individuals treated with ethinyl estradiol 100 µg daily and cyproterone acetate 100 mg daily.28 Therefore, ethinyl estradiol formulations are no longer recommended in GAHT.10 In studies of cisgender women, modern GAHT regimens involving oral or transdermal estradiol have a lower risk of VTE.29,30 As reference, a large observational study in cisgender women reported the OR for VTEs was 1.58 (95% CI, 1.52-1.64) for oral estrogen use but 0.93 (95% CI, 0.87-1.01) for transdermal estrogen use compared to those with no estrogen exposure.31 Additionally, an observational study affirmed that transdermal estrogens carry less thrombotic risk (relative risk, 1.0 [95% CI, 0.9-1.1]), even in women with a prior history of thrombosis compared to placebo.32 Overall, extrapolating from the literature, transdermal estrogen formulations appear to have some of the lowest thrombotic risks (Figure 1).

Recently, the Endocrine Society of America established clinical practice guidelines recommending that serum estradiol levels in those receiving GAHT should not exceed the peak physiological range of 100-200 pg/mL observed in cisgender women. These guidelines aim to avoid supraphysiological estradiol concentrations, which presumably increase the risk of VTE.10,31 These recommendations are derived from sex steroid levels found in premenopAUsal women and serve as a surrogate target to suppress testosterone while minimizing elevated estradiol levels.10 Currently, there are no guidelines or recommendations that we are aware of that comment on the optimal estradiol concentrations to facilitate feminization in transgender individuals. However, it is important to have a discussion with the patient to determine the optimal serum estradiol levels for achieving adequate feminization while managing the potential elevated risk of VTE associated with higher oral estradiol doses observed in postmenopAUsal women.10,31,33

Medical therapy for primary prevention of VTE

Primary prevention refers to the use of anticoagulation or antiplatelet therapy to avoid a first provoked or unprovoked VTE. Robust data supporting the use of direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) or antiplatelet therapy, such as aspirin, for this purpose remain limited.34 Consequently, the American Society of Hematology (ASH) guidelines do not routinely recommend thromboprophylaxis for ambulatory outpatients, except for the use of DOACs in cancer patients for the primary prevention of VTEs.35 In addition, a large database study found no value in the use of aspirin for the primary prevention of VTEs and CVD.36 Given this, there are currently no high-quality data to suggest any benefit in offering medical therapy for the primary prevention of thrombosis in conjunction with GAHT, even in high-risk patients. Until further research provides stronger evidence, we generally do not recommend medical prophylaxis with a DOAC or antiplatelet therapy for primary prevention of VTEs in individuals receiving GAHT.

Perioperative management of GAHT

The number of gender-affirming surgeries performed each year is steadily increasing. However, a lack of evidence-based guidelines regarding VTE prophylaxis during the perioperative period remains. Despite limited evidence to support the discontinuation of GAHT, many surgeons choose to withhold therapy for 2 to 6 weeks preoperatively and resume once patients are reliably ambulating.37,38 However, it is important to note the devastating and negative consequences this may have on transgender patients, potentially exacerbating gender dysphoria.39,40 A large retrospective cohort study found low perioperative risk for patients who continued GAHT. Of the 402 cases reviewed, 190 suspended oral and injectable estrogens for 1 week before surgery, while 212 continued GAHT throughout; these individuals were followed for 289 postoperative days. Only 1 VTE case was reported among the group that suspended estrogen, and no VTE events were reported among those who continued GAHT.41 In addition, multiple systematic review articles report mixed findings regarding the benefit of stopping GAHT prior to surgery.42,43 Therefore, the consensus remains that there is insufficient evidence to suggest that continuing GAHT heightens the risk of postoperative VTE and providers should continue GAHT on a case-by-case basis.43 Moreover, it is important to acknowledge that older individuals face a heightened risk of postoperative VTE, as indicated by the Caprini risk assessment model, which assigns 2 points for patients aged 60-74 years.44 Given the lack of data to support withholding GAHT perioperatively, it is essential for patients and surgeons to discuss the risks and benefits of continuing GAHT during this period. While standard postoperative VTE prophylaxis should be maintained during hospitalization, temporarily withholding or decreasing GAHT in older patients may be considered.

Estrogen treatment after a VTE event in individuals on GAHT

According to ASH guidelines, the primary treatment of VTE should be anticoagulation therapy, with the duration dependent on whether it is a provoked or unprovoked VTE.45 Additionally, ASH guidelines recommend DOACs over antiplatelet therapy for treating VTE in cisgender individuals.46 Due to the limiting data in transgender individuals, those who experienced VTE while on GAHT should receive anticoagulation according to the established guidelines.47 Although there are no randomized clinical trials assessing the safety of continuing GAHT alongside anticoagulation after acute VTE, a large randomized control trial of cisgender women reported that combining estrogen products and anticoagulant therapy is generally safe and reported no association between continuing hormonal therapy and the risk of recurrent/breakthrough VTE in cisgender women receiving concurrent therapeutic anticoagulation.47 Given this evidence, the post-VTE treatment approach in those who wish to continue GAHT should prioritize anticoagulation over antiplatelet therapy, especially for individuals who experienced VTE while on GAHT.

Given the available literature, we suggest that individuals who develop a VTE while on gender-affirming estrogen and wish to continue their GAHT may safely do so if a full-dose anticoagulant is continued concurrently. Due to the risk of recurrent VTE off anticoagulation in those who continue estrogen, we do not recommend stopping anticoagulation. It is reasonable to offer a DOAC concurrently with GAHT, given the relative ease of use. BecAUse of the significant benefits of GAHT in transgender women, treatment should be individualized. Stopping GAHT represents a critical decision for transgender and gender-diverse individuals, potentially carrying negative mental health implications if hormone therapy if discontinued.

CLINICAL CASE 2

A 24-year-old transgender individual who uses he/him pronouns and has a relevant past medical history of essential hypertension and gender-affirming testosterone use presents for follow-up after initiating intramuscular testosterone cypionate 100 mg weekly 6 months prior. The patient has no new symptoms at today's visit; his vital signs are within normal limits, and there are no concerning findings on physical examination. On routine laboratory surveillance for testosterone therapy, a hematocrit of 51% is identified. Three months prior, his hematocrit was 41%.

What we know about thrombosis and polycythemia in patients receiving gender affirming testosterone

Few studies have been performed regarding hematologic adverse events in transgender and gender-diverse patients receiving testosterone for GAHT. From the available data (Table 3), there does not appear to be an increased thrombotic risk, particularly in adolescents and young adults, imparted by gender-affirming testosterone.48 In retrospective studies that have captured thromboembolic events in this population, the incidence has been low, with confounding predisposing thrombotic risk factors.49 The risk of adverse cardiovascular events in transgender individuals on testosterone-based GAHT is another area of ongoing investigation. A retrospective review including 1358 transgender men receiving testosterone found no increased risk of stroke or VTE when compared to both cisgender men and women.50 They did demonstrate an increased risk of MI (standardized incidence ratio 3.69; 95% CI, 1.94-6.42) when compared to cisgender women, but not cisgender men.50

Representative studies on VTE in patients on testosterone based GAHT

| Study . | Patient demographics . | Study type and intervention . | Results . | Conclusions . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mullins et al (2021)48 | 611 adolescents and young adults on GAHT; median age = 17 at initiation of therapy; 68.1% were on testosterone GAHT; N = 611 | Retrospective chart review of patients already on testosterone, primarily IM and SQ formulations; treatment was titrated to physiological normal | No incidental occurrence of arterial or venous thrombosis associated with GAHT was found. | Multiple thrombotic risk factors were noted among the cohort, including obesity, tobacco use, and personal and family history of thrombosis. |

| Oakes et al (2021)49 | Transgender and nonbinary individuals receiving testosterone GAHT; N = 519 | The group performed a retrospective study of patients receiving any form of exogenous testosterone; 90% of patients received IM or SQ formulation. | Thromboembolic events occurred in 5/519 patients (2 superficial vein thromboses, 2 calf vein thromboses, 1 ischemic stroke). Four of these patients met criteria for erythrocytosis at any time during their care, but none met criteria during the event. Two events occurred after surgery, and 2 patients had predisposing risk factors, including tobacco use and recent trAUma. | While 5/519 patients experienced thromboembolic events, none had polycythemia at the time of the event, and the majority had predisposing risk factors. |

| Study . | Patient demographics . | Study type and intervention . | Results . | Conclusions . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mullins et al (2021)48 | 611 adolescents and young adults on GAHT; median age = 17 at initiation of therapy; 68.1% were on testosterone GAHT; N = 611 | Retrospective chart review of patients already on testosterone, primarily IM and SQ formulations; treatment was titrated to physiological normal | No incidental occurrence of arterial or venous thrombosis associated with GAHT was found. | Multiple thrombotic risk factors were noted among the cohort, including obesity, tobacco use, and personal and family history of thrombosis. |

| Oakes et al (2021)49 | Transgender and nonbinary individuals receiving testosterone GAHT; N = 519 | The group performed a retrospective study of patients receiving any form of exogenous testosterone; 90% of patients received IM or SQ formulation. | Thromboembolic events occurred in 5/519 patients (2 superficial vein thromboses, 2 calf vein thromboses, 1 ischemic stroke). Four of these patients met criteria for erythrocytosis at any time during their care, but none met criteria during the event. Two events occurred after surgery, and 2 patients had predisposing risk factors, including tobacco use and recent trAUma. | While 5/519 patients experienced thromboembolic events, none had polycythemia at the time of the event, and the majority had predisposing risk factors. |

GAHT, gender affirming hormone therapy; IM, intramuscular; SQ, subcutaneous.

The risk of polycythemia in transgender individuals on testosterone-based GAHT appears similar to the risk in cisgender men using testosterone for replacement therapy, with incidences of 14.2%-24% reported in representative studies (Table 4). Other factors that contribute to secondary polycythemia, such as sleep apnea, cardiopulmonary pathology, and elevated BMI, are correlated with higher likelihood of hematocrit elevation while on testosterone therapy. In addition, higher testosterone doses and higher serum testosterone levels while on therapy are correlated with polycythemia.51,52 The effects of polycythemia in transgender individuals is another incompletely investigated area. Data regarding risks including VTE, cardiovascular, and cerebrovascular complications attributed to polycythemia are mixed.6,50 The studied adverse effects of secondary polycythemia in cisgender men are discussed below. Providers should note that if the patient is registered as female with the laboratory system, the reported hemoglobin and hematocrit (H/H) ranges are likely within the female reference range. The male laboratory reference ranges for H/H should be used to interpret values from transgender individuals on testosterone therapy.

Representative studies on polycythemia in patients on testosterone GAHT

| Study . | Patient demographics . | Study type and intervention . | Results . | Conclusions . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Porat et al (2023)75 | Individuals taking testosterone for GAHT; N = 282 | In this retrospective cohort study all patients were taking injectable testosterone cypionate, with a median dose of 100 mg weekly. | During the first 20 months of testosterone therapy, the cumulative incidence of hematocrit >50.4% was 12.6%; hematocrit >52% was 1.0%; and hematocrit >54% was 0.6%. | The incidence of polycythemia was 14.2%, with the majority of patients having a hematocrit between 50.4% and 52%. |

| Tatarian et al (2023)52 | Transgender individuals receiving on testosterone for at least 12 months; N = 511 | This retrospective study included patients who were on any kind of testosterone therapy for at least 12 months prior to the start of the study period. They compared patient characteristics between groups who developed polycythemia and those who did not. | Polycythemia occurred in 22%. Increased age, BMI, and dose remained significant variables in the polycythemia group after multivariate analysis. 3/113 patients with polycythemia were determined to experience a thromboembolic complication while on testosterone; 2 of them had DVTs, and 1 had recurrent TIAs. | Polycythemia occurred in 22%, with age, BMI and dose as associated factors. The incidenced of DVT and TIA were not analyzed in comparison to the nonpolycythemia group, likely due to low sample size. |

| Oakes et al (2021)49 | Transgender and nonbinary individuals receiving testosterone GAHT; N = 519 | The group performed a retrospective study of patients receiving any form of exogenous testosterone; 90% of patients received IM or SQ formulation. | 104/519 patients (20%) developed a hematocrit over 50%. The majority with polycythemia were receiving injectable formulations. | 20% of patients developed a hematocrit >50% after starting treatment. |

| Madsen et al (2021)51 | Transgender individuals receiving testosterone at a single center for 20 years; N = 1073 | This retrospective study reviewed transgender individuals receiving any formulation of testosterone who received routine laboratory follow-up while on treatment. | A single measurement of hematocrit >50% occurred in 24.0% of individuals; >0.52% in 7.6%; >0.54% in 2.2%. Erythrocytosis was associated with tobacco use, long-acting undecanoate injections, age at initiation of hormone therapy, BMI, and pulmonary conditions associated with erythrocytosis. | Erythrocytosis occurs in transgender individuals receiving testosterone, typically with hematocrit values between 50% and 52%. The largest increase in hematocrit was seen in the first year of treatment. Risk factors associated with erythrocytosis contribute to its development while on testosterone. |

| Study . | Patient demographics . | Study type and intervention . | Results . | Conclusions . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Porat et al (2023)75 | Individuals taking testosterone for GAHT; N = 282 | In this retrospective cohort study all patients were taking injectable testosterone cypionate, with a median dose of 100 mg weekly. | During the first 20 months of testosterone therapy, the cumulative incidence of hematocrit >50.4% was 12.6%; hematocrit >52% was 1.0%; and hematocrit >54% was 0.6%. | The incidence of polycythemia was 14.2%, with the majority of patients having a hematocrit between 50.4% and 52%. |

| Tatarian et al (2023)52 | Transgender individuals receiving on testosterone for at least 12 months; N = 511 | This retrospective study included patients who were on any kind of testosterone therapy for at least 12 months prior to the start of the study period. They compared patient characteristics between groups who developed polycythemia and those who did not. | Polycythemia occurred in 22%. Increased age, BMI, and dose remained significant variables in the polycythemia group after multivariate analysis. 3/113 patients with polycythemia were determined to experience a thromboembolic complication while on testosterone; 2 of them had DVTs, and 1 had recurrent TIAs. | Polycythemia occurred in 22%, with age, BMI and dose as associated factors. The incidenced of DVT and TIA were not analyzed in comparison to the nonpolycythemia group, likely due to low sample size. |

| Oakes et al (2021)49 | Transgender and nonbinary individuals receiving testosterone GAHT; N = 519 | The group performed a retrospective study of patients receiving any form of exogenous testosterone; 90% of patients received IM or SQ formulation. | 104/519 patients (20%) developed a hematocrit over 50%. The majority with polycythemia were receiving injectable formulations. | 20% of patients developed a hematocrit >50% after starting treatment. |

| Madsen et al (2021)51 | Transgender individuals receiving testosterone at a single center for 20 years; N = 1073 | This retrospective study reviewed transgender individuals receiving any formulation of testosterone who received routine laboratory follow-up while on treatment. | A single measurement of hematocrit >50% occurred in 24.0% of individuals; >0.52% in 7.6%; >0.54% in 2.2%. Erythrocytosis was associated with tobacco use, long-acting undecanoate injections, age at initiation of hormone therapy, BMI, and pulmonary conditions associated with erythrocytosis. | Erythrocytosis occurs in transgender individuals receiving testosterone, typically with hematocrit values between 50% and 52%. The largest increase in hematocrit was seen in the first year of treatment. Risk factors associated with erythrocytosis contribute to its development while on testosterone. |

GAHT, gender affirming hormone therapy; IM, intramuscular; SQ, subcutaneous; TIA, transient ischemic attack.

What we can extrapolate from cisgender men

Several meta-analyses and systematic reviews of cisgender men on testosterone replacement therapy for low testosterone did not show an increased risk of VTE; however, larger studies are needed.53,54 Of note, Walker et al was not included in the most recent meta-analysis due to a lack of available data. This large case-crossover study found a higher risk of VTE in cisgender men with (OR, 2.32; 95% CI, 1.97-2.74) and without (OR, 2.02; 95% CI, 1.47-2.77) hypogonadism receiving testosterone.55 Several smaller studies have noted that cisgender men who develop VTE on testosterone often have underlying hypercoagulable conditions.56,57

Polycythemia in cisgender men receiving testosterone is well studied and is the most common adverse effect. The hematocrit rises in a dose-dependent fashion with testosterone supplementation.58 Although polycythemia itself is well reported, clinically relevant effects of polycythemia are not well understood. Secondary polycythemia due to other cAUses does not appear to invoke an increased risk of VTE, although data are not conclusive.58-60 A review by Jones et al reported a 315% increase in the risk of polycythemia in cisgender men receiving testosterone; however, they found that data regarding an increased VTE risk in those who developed polycythemia were inconclusive.61 A large case control study in the United Kingdom demonstrated an increased rate of VTE in patients during the first 6 months of testosterone therapy, with a rate ratio of 1.63 (1.12-2.37). However, a separate analysis investigating whether there is an increased risk specifically in those with polycythemia was not conducted.62 The Endocrine Society of America's 2018 guidelines on testosterone for androgen deficiency syndromes note that too few testosterone-related VTE events in randomized controlled trials are available to draw meaningful inferences.63

The risk of major adverse cardiovascular events in cisgender men who develop polycythemia while on testosterone therapy is another area of conflicting data.64 In a recent cohort study of 5842 cisgender men receiving testosterone therapy, those who developed polycythemia were matched with those who did not develop polycythemia; the study showed that cisgender men with polycythemia had a higher risk of acute myocardial infarction (OR 1.81, 95% CI 1.2-2.7) and VTE (OR 1.51, 95% CI 1.17-1.94) compared to cisgender men who had normal hematocrit. However, the risk of death and stroke was not increased.1

How to approach polycythemia

Testosterone-associated polycythemia is defined as hematocrit >50% by the Endocrine Society of America. In cisgender men on hormone replacement therapy for hypogonadism, current guidelines recommend discontinuation of testosterone at hematocrit levels >54% before proceeding with a lower dose.63 Lowering the dose remains a potential consideration in transgender and gender-diverse individuals; however, this may result in loss of desired effects. Ideally, the titration of masculinizing therapy is aimed to balance between achieving the patient's desired effects and preventing the patient's individual risks, including polycythemia. Given that there remain unclear data regarding both the thrombotic and cardiovascular risks of polycythemia, particularly in transgender individuals, determining acceptable hematocrit ranges can be challenging. GAHT is medically necessary, and the risks of dose reduction or cessation, including potential detrimental effects on mental health, should be balanced with the uncertainty of the adverse effects of polycythemia and various treatment modalities, including phlebotomy, within this population. Shared decision-making surrounding potential unknown harm is essential.

Topical, intramuscular, and subcutaneous routes of administration are all treatment options. In hypogonadal cisgender men, transdermal application of testosterone has been shown to result in lower levels of hematocrit elevation than intramuscular injection.65 Transition to an alternative formulation with less risk of polycythemia, and avoidance of long-acting intramuscular or subcutaneous testosterone formulations, is a reasonable initial strategy for individuals on testosterone GAHT. Unfortunately, the feasibility of alternative formulations may be limited by logistical constraints. While phlebotomy is sometimes used to correct polycythemia, the utility of this approach is unstudied, and the risks of iatrogenic iron deficiency should be considered. In general, modern guidelines discourage this practice for nonclonal forms of polycythemia, which has been our base case recommendation, although each patient is treated on a case-by-case basis.66 Importantly, investigation of pathologic cAUses of polycythemia, including obstructive sleep apnea, tobacco use, and myeloproliferative neoplasms, should be conducted.

How to approach iron deficiency

Increases in hematocrit with testosterone supplementation are associated with decreased levels of ferritin and hepcidin along with increased levels of erythropoietin. While erythropoietin levels return to baseline over time, they are not depressed despite elevated hematocrit, resulting in increased iron utilization.67,68 Additionally, while testosterone treatment typically eliminates menstruation, some patients may continue to experience menses, particularly during the early stages of treatment. Continued heavy menstrual bleeding is another factor to consider regarding the risk of iron deficiency in this population. Clinicians should consider obtaining a baseline ferritin level and repleting iron if indicated prior to initiation of therapy. During subsequent visits, patients should be regularly monitored for any signs or symptoms of iron deficiency.

Conclusion

The current understanding regarding the risk of VTE in transgender and gender-diverse individuals is progressing. Recent data suggest that transdermal options carry the lowest risk of VTE for transgender individuals. However, the data remain varied, emphasizing the necessity for further research into the long-term hematologic effects of GAHT. For those who develop VTE while on GAHT, current recommendations advocate for administering anticoagulation therapy following ASH guidelines. Discontinuing GAHT after a VTE lacks substantial data support and may be unnecessary if anticoagulation therapy is concurrently provided.38

Modifiable risk factors, such as BMI over 35 kg/m2, can influence an increased VTE risk. Further, smoking exacerbates cardiovascular risks, including VTE, by impacting insulin resistance, blood pressure, heart rate, and lipid levels.69 Hormone replacement therapy with estrogen is known to increase cardiovascular risk in cisgender individuals, but the impact of GAHT on cardiovascular risk in transgender individuals remains unclear. Research should prioritize investigating the long-term cardiovascular effects of GAHT to improve understanding of associated risks. Primary prevention of thromboembolic events for individuals on GAHT is not recommended until more substantial evidence becomes available. The existing literature suggests that continuing GAHT may not significantly heighten postoperative VTE risk, yet a shared decision-making discussion is advised before continuing GAHT perioperatively.

Data available for both cis and transgender individuals receiving testosterone regarding thrombosis are reassuring and suggest against an increased risk with testosterone therapy. Larger prospective studies are needed to better understand the risks of polycythemia and thromboembolism in this patient population as well as to develop evidence-based treatment strategies. While there is no definitive approach to polycythemia, hematocrit level, individual patient risk factors, and desired effects of therapy all need to be balanced. Dose reduction and transitioning to transdermal formulations are appropriate strategies to consider in shared decision-making conversations with the patient. The importance of GAHT and the unknown adverse effects of polycythemia in this population should be heavily weighed. Unclear evidence surrounding the adverse effects of testosterone GAHT, including cardiovascular and cerebrovascular risk, should also be discussed with the patient.70 Further, testosterone treatment can increase iron utilization; thus, a baseline ferritin value can be helpful to prevent worsening a preexisting iron deficiency.

Acknowledgment

Joseph J. Shatzel is supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute/National Institutes of Health (R01HL151367).

Conflict-of-interest disclosure

Hannah King: no competing financial interests to declare.

Thalia Padilla Kelley: no competing financial interests to declare.

Joseph J. Shatzel reports receiving consulting fees from Aronora Inc.

Off-label drug use

Hannah King: nothing to disclose.

Thalia Padilla Kelley: nothing to disclose.

Joseph J. Shatzel: nothing to disclose.