Abstract

Thrombocytopenia will occur in 10% of pregnancies—ranging from the clinically benign to processes that can threaten both mother and fetus. Accurately identifying the specific etiology and appropriate clinical management is challenging due to the breadth of possible diagnoses and the potential of shared features among them. Further complicating diagnostic certainty is the lack of confirmatory testing for most possible pathophysiologies. Immune thrombocytopenia (ITP) is recognized in less than 0.1% of pregnancies but is the most common cause of thrombocytopenia in early trimesters. ITP is an autoimmune disease of IgG-mediated enhanced platelet clearance and reduced platelet production. While there is an increasing number of drugs approved to treat ITP and more being examined in clinical trials, few have been sufficiently studied in pregnancy, representing a major unmet need in clinical practice. As such, treatment options for ITP in pregnancy are limited to corticosteroids and immunoglobulin therapy, which will not be effective in all cases. Maternal ITP also may have fetal impact, and any proposed therapeutic intervention must account for this possibility. Optimal care requires multidisciplinary collaboration between hematology, obstetrics, and anesthesia to enhance diagnostic clarity, develop an optimized treatment regimen, and shepherd mother and neonate to delivery safely.

Learning Objectives

Identify the correct etiology of thrombocytopenia in pregnancy by applying a systematic approach to diagnostics focused by severity and trimester of onset.

Determine the appropriate timing for active treatment of maternal ITP, goals of intervention, and expected benefits and side effects of first-line therapy.

Understand how to apply the limited data of second-line interventions to the patient in need of additional therapy.

Introduction

Thrombocytopenia will be encountered in 7%-11% of all pregnancies1-4 and is defined as any platelet count less than 150 000/µL. While thrombocytopenia may occur at any stage of pregnancy, it is most common in the third trimester. The differential diagnosis of thrombocytopenia is broad, ranging from benign to life-threatening conditions that can impact both mother and fetus. A diagnosis of immune thrombocytopenia (ITP) requires a platelet count of less than 100 000/µL. Most cases of thrombocytopenia in pregnancy will be due to processes exclusive to pregnancy, such as gestational thrombocytopenia (GT) and preeclampsia, but any cause of thrombocytopenia can affect a pregnant patient and therefore must be considered in a systematic fashion. Deciphering the etiology of thrombocytopenia in pregnancy is a challenge, as multiple syndromes have overlapping laboratory and clinical features and most lack a confirmatory test. The extensive differential of potential diagnoses is best narrowed by considering the severity of thrombocytopenia and when in the pregnancy it was first appreciated.

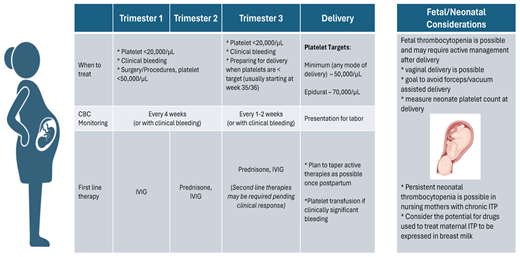

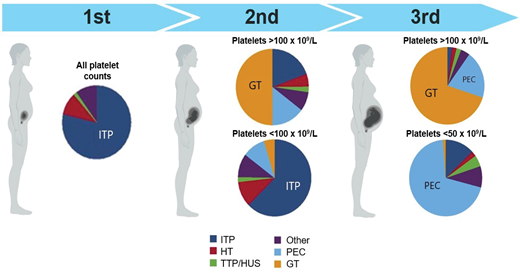

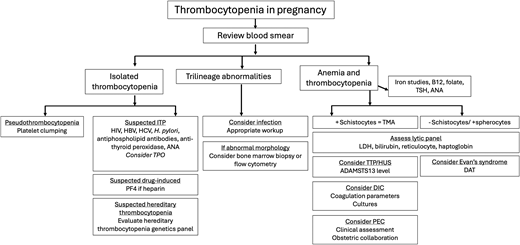

The relative proportion of diagnoses stratified by trimester and severity is displayed in Figure 1. Following the trimester designation, the next diagnostic branch point is whether thrombocytopenia is isolated or part of a systemic syndrome. The peripheral smear review is invaluable for diagnostic clarity. Schistocytes, which are the hallmark feature of thrombotic microangiopathies (TMAs) will be absent in ITP. As ITP remains a diagnosis of exclusion, a consistent diagnostic approach and supportive panel of laboratory tests is advised and outlined in Figure 2.

Causes of thrombocytopenia in pregnancy by trimester of presentation and severity. HT, hereditary thrombocytopenia; PEC, preeclampsia; TTP/HUS, thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura/hemolytic uremic syndrome.

Causes of thrombocytopenia in pregnancy by trimester of presentation and severity. HT, hereditary thrombocytopenia; PEC, preeclampsia; TTP/HUS, thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura/hemolytic uremic syndrome.

Diagnostic approach to thrombocytopenia in pregnancy. ANA, antinuclear antibody; DAT, direct antiglobulin test; DIC, disseminated intravascular coagulation; HBV, hepatitis B virus; HCV, hepatitis C virus; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; PEC, preeclampsia; PF4, platelet factor 4; TMA, thrombotic microangiopathy; TPO, thrombopoietin; TSH, thyroid stimulating agent; TTP/HUS, thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura/hemolytic uremic syndrome.

Diagnostic approach to thrombocytopenia in pregnancy. ANA, antinuclear antibody; DAT, direct antiglobulin test; DIC, disseminated intravascular coagulation; HBV, hepatitis B virus; HCV, hepatitis C virus; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; PEC, preeclampsia; PF4, platelet factor 4; TMA, thrombotic microangiopathy; TPO, thrombopoietin; TSH, thyroid stimulating agent; TTP/HUS, thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura/hemolytic uremic syndrome.

CLINICAL CASE 1

A 32-year-old patient G1P0 at 15 weeks is evaluated for platelets of 53 000/µL. Her complete blood count (CBC) is otherwise normal. She is well appearing, afebrile, and normotensive. There is no history of bleeding or bruising. She takes a prenatal vitamin and probiotics. There is no personal or family history of thrombocytopenia or abnormal bleeding episodes. A CBC from 5 years prior show a normal platelet count of 224 000/µL. On exam, there is no lower extremity edema, hepatosplenomegaly, or lymphadenopathy. Her skin exam is free of rash, purpura, petechiae, or bruising.

Initial Considerations: At 15 weeks with a platelet count <100 000/µL, ITP is the most likely diagnosis (Figure 1). The patient has isolated thrombocytopenia without an obvious infectious process or generalized syndrome. There is no history of autoimmune syndromes; tests for antinuclear antibodies, antiphospholipid antibodies, and H. pylori antibodies are negative. Coagulation and liver function tests are normal. She was previously assessed for HIV, hepatitis C virus, and hepatitis B virus in pregnancy; all results were negative. Analysis of her peripheral blood smear confirms thrombocytopenia with large platelets but no schistocytes. The normal platelet count from several years prior lessens suspicion for hereditary thrombocytopenia.

ITP pathophysiology

ITP is defined as a platelet count <100 000/µL without other explanations or cytopenias.5 The pathophysiology of ITP is due to antiplatelet antibodies and lymphocytes that enhance platelet destruction and inhibit megakaryocytic production of platelets.6,7 Antiplatelet antibodies that target glycoproteins (GPs) IIb/IIIa, Ib/IX, and Ia/IIa8 are able to cross the placenta and have been documented in 80% of nonpregnant patients with ITP. These antibody-coated platelets are then cleared from circulation by splenic and circulatory macrophages through Fc γ receptor engagement. The expected compensatory rise in platelet production from megakaryocytes is often blunted by the very same antibodies or inhibitory lymphocytes.9-11

ITP in pregnancy

Approximately 0.1% of all pregnancies4 will have an ITP diagnosis, which can present in any trimester. While overall uncommon, it is the most likely diagnosis when thrombocytopenia occurs in the first or early second trimesters.12 While a higher number of affected women will carry a previous diagnosis of ITP or thrombocytopenia, for 30%, this will be the index ITP event.13 ITP will persist after delivery in the majority of cases.14

A prospective observational cohort study comparing clinical events between 131 pregnant women with ITP and 131 nonpregnant women with ITP found no difference in rates of severe bleeding, but pregnant patients with ITP were more likely to experience a platelet count <30 000/µL (hazard ratio 2.71) and need treatment modification (hazard ratio 2.01). In this series, 14% of neonates had a platelet count <50 000/µL, which meets criteria for neonatal ITP (NITP). The highest risk for NITP was the mother having a previous offspring with NITP or a maternal platelet count of <50 000/µL within 3 months of delivery.15 A meta-analysis of 1043 pregnancies with ITP concluded that a first-time diagnosis of ITP is not associated with poor outcomes, with weighted event rates of 0.181 for bleeding (mostly nonsevere bleeding), 0.053 for severe postpartum hemorrhage, 0.014 for intracranial hemorrhage (ICH), and 0.122 for NITP.16

There is no definitive evidence that a different mechanism is responsible for ITP in pregnant patients compared to nonpregnant patients or that pregnancy alters antiplatelet production or platelet destruction by macrophages. However, a dysfunctional immune response to the normal shift from Th2 toward Th1 cytokines in late gestation may promote autoantibody formation and trigger the development of ITP.17 In addition, observations that pregnant women with ITP have an increased thrombopoietin (TPO) level compared to nonpregnant patients with ITP18 may suggest that impaired platelet production is a larger contributor to ITP pathophysiology in pregnancy than it is in nonpregnant patients.

When isolated thrombocytopenia occurs in an otherwise healthy patient in late pregnancy, the primary differential is ITP and GT. While distinguishing between the two is often readily apparent by platelet trend, it is more difficult when the platelet count ranges from 60 000/µL to 90 000/µL. In such cases, TPO level18 or antiplatelet antibodies in platelet eluate19 may assist in differentiating ITP from GT.

First line treatment of ITP in pregnancy

The target platelet count that will prompt treatment for ITP varies by stage of pregnancy. Current guidelines20,21 state that treatment can be deferred during the first 8 months of pregnancy unless there is clinically significant bleeding or the platelet count falls below 20 000/µL. However, the target platelet count for delivery increases to 50 000/µL21,22 to meet the significant hemostatic challenge that placental separation introduces. The target platelet count is further increased to 70 000/µL when epidural anesthesia is intended, although there are no randomized data that examine the safety of different platelet thresholds. An interdisciplinary consensus statement of the Society of Obstetric Anesthesia and Perinatology (SOAP) finds that the risk of spinal epidural hematoma is very low with platelets >70 000/µL in patients with ITP, GT, or hypertensive disorders of pregnancy in the absence of additional risk factors.23 Multiple retrospective studies demonstrate low to no complications of epidural anesthesia even when the platelet count is <100 000/µL.24-27 The likelihood of an epidural hematoma is estimated at 1 per 150 000 in the general population28 and reported as 0.2-3.7 per 100 000 in obstetric cases.29

The optimal mode and timing of delivery should be based on obstetrical indications, although spontaneous vaginal delivery is preferred when possible. The incidence of NITP is reported as 8.9-14.7%, with fetal intracranial hemorrhage (ICH) occurring in 1.5% of cases.15,30 This is compared to rates of ICH of 7-26% in cases of neonatal alloimmune thrombocytopenia.31 Although the rate of ICH in NITP is overall low, attempts to instrument the fetus with forceps or vacuum delivery should be avoided. Of note, neonates with normal platelets at birth can experience a decrease in platelets and nadir 4 days to 1 week after delivery. Thus, ongoing monitoring of at-risk neonates is appropriate.

Corticosteroids and intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) are the mainstays of treatment for ITP in pregnancy. In a retrospective study of 195 women with ITP who had 235 pregnancies, 137 pregnancies did not require active treatment. Of the 98 pregnancies (42%) requiring treatment, IVIG and steroids resulted in similar initial response rates (38% vs 39%), defined as a platelet count >100 000/µL or a platelet count that doubled from baseline but remained 30 000 to 100 000/µL.32 There was an 80% response rate when IVIG was added after corticosteroids.32 While the response rate of less than 40% is lower than typically observed in nonpregnant cohorts treated with steroids or IVIG,33 this disparate response has not been uniformly observed in pregnancy34,35 and is not our local experience.

Prednisone is the corticosteroid of choice in pregnancy owing to lower crossover into cord blood than dexamethasone, which has less efficient placental metabolism and thus yields higher fetal concentrations.36 Although platelet response to dexamethasone is generally quicker, a response to prednisone is typically evident within 2 to 3 days.37 A concern of corticosteroid use in the first trimester is an increased risk of cleft palate and urogenital congenital anomalies, although overall reports are rare.38-40

Prednisone can usually be deferred until 35 to 36 weeks, when preparations for delivery ensue. This approach limits steroid exposure, reducing the likelihood of side effects, including gestational diabetes, hypertension, mood lability, gastrointestinal distress, or insomnia.41 Following initiation, corticosteroids are typically continued through delivery and then tapered after delivery as long as platelets remain greater than 20 000/µL. For steroid-naive patients, a brief pulse of prednisone (such as 40 mg daily for 5 days) can be considered at weeks 30 to 32 to assess response and theoretically permit time to initiate second-line therapies in a nonresponder (Table 1).

Therapeutic options and considerations for treatment of ITP during pregnancy and lactation

| Treatment . | Dosing . | Response rates (%) . | Time to response . | Maternal considerations . | Fetal considerations . | Lactation xonsiderations . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FIRST LINE | ||||||

| Prednisone | 20-60 mg/d | 40-70 | 3-14 days | HTN, diabetes, premature delivery, insomnia, mood lability, fluid overload | Hypoglycemia, prematurity, risk for cleft palate when exposed in first trimester | Low risk |

| IVIG | 0.4 g/kg up to 5 days or 1 g/kg for 1-2 days | 40-80 | 1-3 days | Headache, fluid overload, HTN, aseptic meningitis, myalgias, hemolysis | Hemolysis | Low risk |

| SECOND LINE (Minimal data available. No uniform recommendations exist regarding optimal agent.) | ||||||

| Not recommended in pregnancy, but use described | ||||||

| Romiplostim | 1-10 µg/kg/wk | 70-80 | 7-14 days | Headache, myalgia | Thrombocytosis | Limited data, thus not advised Detected in breast milk50,51 |

| Eltrombopag | 25-75 mg/d | 70-80 | 7-14 days | Elevated LFTs, headache | Thrombocytosis | Limited data, thus not advised |

| Cyclosporine | 3-5 mg/kg of body weight/d | Insufficient data on ITP in pregnancy to calculate | 4-12 weeks | Renal injury, HTN, tremor | IUGR | Present in breast milk Monitor for neonate infection |

| Rituximab | 375 mg/m2 weekly × 4 | 40-60 | 1-8 weeks | Infusion reaction, hypogammaglobulinemia, infection, curtailed vaccine response | Hypogammaglobulinemia, reduced B cells | Minimal concentrations, low risk |

| Azathioprine | 50-75 mg/d | Insufficient data on ITP in pregnancy to calculate | 8-16 weeks | Transaminitis, neutropenia, infection | Case reports of use in renal transplant recipients with congenital anomalies, heme toxicity, and IUGR | Neonate neutropenia has been reported. Avoidance or neonate CBC monitoring advised |

| Generally contraindicated in pregnancy, but use described | ||||||

| Dapsone | 100 mg/d | 40-50 | 7-14 days | Hemolysis | Anemia, prematurity | Hemolytic anemia reported (check G6PD level and monitor CBC) |

| RhD immune globulin | 50 µg/kg of body weight | 70 | 4-5 days | *Limit use to nonsplenectomized patients Hemolysis, renal failure, infusion reaction | Anemia, jaundice | Low risk |

| Splenectomy | Optimal timing is early second trimester or before pregnancy | 50-80 | 1-60 days | Bleeding, infection, thrombosis risk, preterm labor | Prematurity | Minimal risk |

| CONTRAINDICATED IN PREGNANCY | ||||||

| Vinca alkaloids Cyclophosphamide Mycophenolate mofetil Danazol Fostamatinib | ||||||

| Treatment . | Dosing . | Response rates (%) . | Time to response . | Maternal considerations . | Fetal considerations . | Lactation xonsiderations . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FIRST LINE | ||||||

| Prednisone | 20-60 mg/d | 40-70 | 3-14 days | HTN, diabetes, premature delivery, insomnia, mood lability, fluid overload | Hypoglycemia, prematurity, risk for cleft palate when exposed in first trimester | Low risk |

| IVIG | 0.4 g/kg up to 5 days or 1 g/kg for 1-2 days | 40-80 | 1-3 days | Headache, fluid overload, HTN, aseptic meningitis, myalgias, hemolysis | Hemolysis | Low risk |

| SECOND LINE (Minimal data available. No uniform recommendations exist regarding optimal agent.) | ||||||

| Not recommended in pregnancy, but use described | ||||||

| Romiplostim | 1-10 µg/kg/wk | 70-80 | 7-14 days | Headache, myalgia | Thrombocytosis | Limited data, thus not advised Detected in breast milk50,51 |

| Eltrombopag | 25-75 mg/d | 70-80 | 7-14 days | Elevated LFTs, headache | Thrombocytosis | Limited data, thus not advised |

| Cyclosporine | 3-5 mg/kg of body weight/d | Insufficient data on ITP in pregnancy to calculate | 4-12 weeks | Renal injury, HTN, tremor | IUGR | Present in breast milk Monitor for neonate infection |

| Rituximab | 375 mg/m2 weekly × 4 | 40-60 | 1-8 weeks | Infusion reaction, hypogammaglobulinemia, infection, curtailed vaccine response | Hypogammaglobulinemia, reduced B cells | Minimal concentrations, low risk |

| Azathioprine | 50-75 mg/d | Insufficient data on ITP in pregnancy to calculate | 8-16 weeks | Transaminitis, neutropenia, infection | Case reports of use in renal transplant recipients with congenital anomalies, heme toxicity, and IUGR | Neonate neutropenia has been reported. Avoidance or neonate CBC monitoring advised |

| Generally contraindicated in pregnancy, but use described | ||||||

| Dapsone | 100 mg/d | 40-50 | 7-14 days | Hemolysis | Anemia, prematurity | Hemolytic anemia reported (check G6PD level and monitor CBC) |

| RhD immune globulin | 50 µg/kg of body weight | 70 | 4-5 days | *Limit use to nonsplenectomized patients Hemolysis, renal failure, infusion reaction | Anemia, jaundice | Low risk |

| Splenectomy | Optimal timing is early second trimester or before pregnancy | 50-80 | 1-60 days | Bleeding, infection, thrombosis risk, preterm labor | Prematurity | Minimal risk |

| CONTRAINDICATED IN PREGNANCY | ||||||

| Vinca alkaloids Cyclophosphamide Mycophenolate mofetil Danazol Fostamatinib | ||||||

G6PD, glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase; HTN, hypertension; IUGR, intrauterine growth retardation; LFTs, liver function tests;.

If prednisone fails to achieve the desired platelet target, IVIG is added to the regimen. IVIG is delivered in divided doses over 1-5 consecutive days for a total dose of 0.4-2 g/kg.42,43 In the nonemergent patient, a lower daily dose of IVIG 0.4 g/kg is preferred to mitigate side effects. When there is limited time until delivery, IVIG 1 g/kg daily for 2 consecutive days should be administered, although higher doses can cause significant headaches that may raise concern of cerebral hemorrhage and require imaging to exonerate.

It is important to highlight that the clinical severity of ITP and its response to treatment is heterogeneous and may be further compounded by clinical variables of pregnancy. As such, counseling the pregnant patient with ITP about the potential for a failed response to therapy despite a methodical and layered approach is essential so that the patient may have time to investigate alternative pain management strategies if epidural is not possible as well as understand the risk for and management of bleeding in the event of delivery with persistent thrombocytopenia.

CLINICAL CASE 1 (continued)

No treatment is indicated for the first 8 months of pregnancy given absence of bleeding and a platelet count consistently greater than 20 000/µL. Her CBC is trended every 4 weeks through the second trimester, and every 1-2 weeks in the final trimester. She is counseled that treatment will likely be required closer to term.

Platelet counts were 53 000 to 69 000/µL during weeks 15-32, down to 45 000/µL at week 33. No bleeding or hypertension were noted. Blood smears never demonstrated schistocytes on serial examinations. At 36 weeks, prednisone 60 mg daily is started with brisk platelet response to 81 000/µL after 1 week. She presents in spontaneous labor at 38 weeks with a platelet of 88 000/µL. An epidural is placed, and vaginal delivery is uncomplicated. Her neonate had a normal platelet count. Following a rapid steroid taper over 10 days, the platelet count decreased to 80 000/µL and remained in this range for the next year. She now carries a diagnosis of chronic ITP but has not required active management.

CLINICAL CASE 2

A 31-year-old female G1P1001 is referred to hematology during prepregnancy counseling given a history of ITP. She is currently managed with eltrombopag 75 mg daily. Her platelet count is 32 000/µL. She was initially diagnosed with ITP 3 years ago in her first pregnancy with a platelet count of 11 000/µL and otherwise normal CBC at 18 weeks. At the time, she was started on prednisone 60 mg daily, achieving a peak platelet count of only 21 000/µL after several weeks of use. She was thus transitioned to IVIG, initially at 0.5 g/kg every 2-3 weeks, which was escalated to daily for 4 days starting at week 36. Her maximum platelet count was 48 000/µL. She was unable to receive an epidural. She delivered vaginally without complications. Her neonate had a platelet count of 63 000/µL at birth, with a subsequent nadir of 39 000/µL on day 3 that was treated with IVIG and resolved by 3 weeks. There were no bleeding complications. She is planning another pregnancy in the coming year and interested in alternative therapy options.

Second-line therapies

There is no standard approach to second-line therapy in maternal ITP when corticosteroids and IVIG are ineffective. As steroids and IVIG are typically introduced only nearing delivery, a failed response provides little time for a meaningful response to second-line agents. Despite the increasing number of drugs available to treat ITP in the nonpregnant population, both approved or via clinical trials, few have been critically examined in pregnancy. Available safety data in pregnancy for drugs such as azathioprine, dapsone, and cyclosporine are derived almost entirely from non-ITP indications, with a usual onset of response being several weeks.20 Rituximab has been used in pregnancy at standard dosing over 4 weeks, but the response may be delayed by up to 8 weeks, and the use also introduces the risk for neonatal hypogammaglobulinemia when administered in the third trimester.

In very rare cases, splenectomy has been performed in pregnancy; however, surgical difficulty in the presence of a gravid abdomen increases the operative risk. Thus, the second trimester would be optimal for splenectomy but has usually passed by the time refractory ITP is evident.

Platelet transfusion is only transiently beneficial; it is thus reserved for acute bleeding and not appropriate to mitigate epidural catheter risk, for which a stable platelet count exceeding 70 000/µL is desired from placement through 2 hours after removal.

Recombinant human TPO (rhTPO) and the TPO receptor agonists (TPO-RAs) have transformed ITP care and are well tolerated and highly effective44-46; however, these agents are not approved for use in pregnancy given scant safety data from limited off-label use. They remain appealing, however, as available data suggest similar efficacy in pregnant patients, with usual onset of response in less than 2 weeks. There is only 1 rhTPO (exclusive to China), however, that does not cross the placenta. A single prospective study of TPO agents in pregnancy47 included 31 women who did not respond to corticosteroids and IVIG with platelets <30 000/µL near delivery and were treated with rhTPO daily for 14 days. Ten (32%) reached a platelet count over 100 000/µL, and 23 (74%) achieved a platelet count over 30 000/µL. There were minimal adverse events, including no maternal or neonatal bleeding.

The TPO-RAs (romiplostim, eltrombopag, avatrombopag) all cross into fetal circulation, although preclinical animal toxicity studies demonstrated fetal effects only at doses significantly higher than that used clinically in humans.48 There are no published data describing use of avatrombopag in pregnancy. A retrospective analysis of TPO-RAs used in the third trimester in 17 pregnancies (eltrombopag in 8, romiplostim in 7) demonstrated a platelet response from a median baseline of 10 000/µL to a median of 94 000/µL without bleeding, clinically symptomatic thromboembolic events, or other serious adverse events. Two patients reported a mild headache.49 Median TPO-RA exposure was 4.4 weeks. Six neonates (33%) had thrombocytopenia and 1 had thrombocytosis (platelets 558 000/µL). No fetal losses or birth defects were attributable to TPO-RA; 29% delivered preterm at 34-38 weeks.

Based on currently available data, TPO-RAs should be restricted to patients with insufficient responses to corticosteroids and IVIG, only in the last trimester, and when no other options are available. If used, romiplostim is preferred given fewer off-target effects (eg, no iron chelation as is seen with eltrombopag). A summary of the treatments for ITP in pregnancy is provided in Table 1.

CLINICAL CASE 2 (continued)

Chronic ITP is not a contraindication to pregnancy, but it does merit a thoughtful and frank discussion of management options and risks. Although romiplostim may be considered in the final month of pregnancy if needed for delivery management, presently there are insufficient safety data to endorse TPO-RA use throughout all trimesters. She is thus advised to come off eltrombopag before another pregnancy. We must prepare for the expected decline in platelets as eltrombopag is gradually discontinued and anticipate similar limited responses to steroids and IVIG. Women can safely conceive as soon as their TPO-RA is discontinued, although a brief window to observe platelet trend and intervene if indicated is preferred.

We review options for agents that, if effective, could be continued in pregnancy, such as azathioprine, which is estimated to have a 40%-50% response rate in nonpregnant patients. Rituximab is another option, but she is concerned about the risk for diminished responses to vaccinations after a rituximab course and thus rejects this option. She ultimately opts for elective splenectomy, which is scheduled after appropriate vaccinations. Splenectomy offers a 70% response rate that is enduring in most patients. With the emergence of many new and effective drugs, splenectomy is rarely used to treat ITP; however, women of reproductive age remain a population where splenectomy still has a role, given limited studies of treatment options and the complexities of management in pregnancy and lactation. Splenectomy should not be considered until the need for chronic management of ITP is observed over 1 year. She continues eltrombopag through splenectomy, also receiving a course of IVIG 0.5 g/kg daily for 4 consecutive days the week before surgery. Her platelet count was 98 000/µL the day of surgery, which increased to 678 000/µL 1 week postoperatively. Eltrombopag was discontinued, and she was managed with venous thromboembolism chemoprophylaxis for 2 weeks postoperatively. Her platelets remained greater than 200 000/µL for the following 8 months when she conceived, and remained greater than 80 000/µL throughout her second pregnancy without the need for therapy. She was able to receive neuraxial anesthesia; there were no bleeding complications. Her neonate was born with a normal platelet count.

Conclusion

Diagnosis and treatment of the pregnant patient with thrombocytopenia is ideally conducted through a collaborative approach between hematology, obstetrics, and anesthesia. As ITP remains a diagnosis of exclusion, a uniform approach to diagnostics and monitoring should be undertaken for each patient with thrombocytopenia. While steroids and IVIG have a track record of safety in pregnancy, patients should be counseled on the expected response rates and side effects as well as the realities of the limited options that exist in second-line therapies. While TPO-RAs have not been associated with any significant safety concerns when used in the final 4 weeks of pregnancy, before they can be considered for routine use, further studies are needed to assess their safety when used for longer intervals. Clinical trials or robust registry data that specifically examine the maternal and fetal safety of novel agents being used to treat ITP in the nonpregnant population remain much needed.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure

Annemarie E. Fogerty: no competing financial interests to declare.

Off-label drug use

Annemarie E. Fogerty: TPO-RAs are not currently approved for use in pregnancy.