Visual Abstract

Inherited bleeding disorders (IBDs) are a heterogeneous group of diseases presenting with variable bleeding severity that require life-long treatment, which is costly and complex. Delivering care to IBDs is a challenge for less-resourced countries. We aimed to describe the strategies used to implement an IBD program, as a health public policy, in a lower- to middle-income country, and its impact on reported outcomes. We collected information from scientific articles searched in LILACS, SciELO, and PubMed. We also accessed documents (guidance, leaflets, surveys, protocols) published by the Brazilian IBD Program/Ministry of Health. The topics analyzed were mainly related to the implementation of a national registry, procurement of clotting factor concentrates (CFC) and procoagulants, incorporation of new technologies in IBDs, and education of caregivers, patients, and their families. We showed that the policies implemented promoted an increment in the registration and diagnosis of people with IBDs, the institution of a more transparent and cost-effective system for the procurement of CFC and procoagulants (including an increase in the portfolio of products and quantities purchased), reduction in the prevalence of anti-factor VIII inhibitors, progressive increase of people with hemophilia under prophylaxis, better qualification of caregivers, patients, and families and, maybe, reduced mortality of people with hemophilia. The IBDs program implemented in Brazil is a real-life example of a successful public health policy in a lower- to middle-income country, and may serve as a model for IBD care to other countries with similar economies.

Introduction

Inherited bleeding disorders (IBDs) refer to a heterogeneous group of rare bleeding diseases of variable severity, with prevalence ranging from 1:1000 to 1:2 000 000.1 IBDs require life-long treatment, which is complex and costly. Treatment usually demands IV infusion of clotting factor concentrates (CFCs) and/or blood products and/or procoagulants on a prophylactic and/or episodic basis. Of all IBDs, hemophilia and von Willebrand disease (VWD) are the most prevalent conditions. Other, rarer IBDs refer to the deficiency of coagulation factors I, II, V, VII, X, XI, XIII, combined deficiencies, and platelet disorders.

Congenital hemophilia results from the deficiency of coagulation factor VIII (hemophilia A) or IX (hemophilia B), due to mutations in the coding genes of these proteins. The severity of hemophilia varies according to the plasma levels of factor VIII or IX, which define the disorder as severe, moderate, or mild.2 People with hemophilia and a bleeding phenotype should be treated prophylactically with the deficient CFC (factor VIII or IX concentrate) or nonfactor therapies.3 In general, patients without a bleeding phenotype can be treated episodically, after a bleeding episode occurs.

IBDs may affect patients’ life spans during an entire age spectrum. Beyond expenses with CFC and other procoagulants, people with IBDs require a myriad of health care interventions aimed at preventing and/or treating bleeding and disease complications. Furthermore, IBDs care requires a trained and dedicated multidisciplinary team and specialized laboratories. Altogether, IBDs and, particularly hemophilia care, are challenging for health care systems and policy-makers due to the high costs involved, even for high-income countries.4 Therefore, working with governments and other stakeholders is vital for a successful establishment of a public policy in IBDs.

Over the past 5 decades, IBDs care has greatly improved worldwide, despite inequality in health care between high- and less-resourced countries.5 Indeed, ∼75% of people with IBDs live in low- to middle-income countries,6 of whom thousands have not even been diagnosed. According to the 2023 Annual Survey of the World Federation of Hemophilia,7 2 indicators clearly illustrate the opportunities for improvement in hemophilia care worldwide. Firstly, the number of patients diagnosed is much lower than the estimated number based on the expected prevalence according to the population of each country. Secondly, the per capita use of factors VIII and IX is substantially lower than that recommended for minimally qualified care.8 For both metrics, low- to middle-income countries concentrate the worse results, thus confirming the impact of socioeconomic conditions on health inequality in hemophilia care. As a corollary, strategies proved to be successful in high-income countries, more commonly reported in the scientific literature, do not necessarily apply to lower-income ones with similar effectiveness.

In this context, reports on the experience of IBD care in lower-income countries may offer a complementary and attractive perspective for countries sharing similar socioeconomic backgrounds. Herein, we present and discuss the implementation of a national program for IBDs care developed in Brazil, focusing on the period between 2004 and 2024. For this, we collected information from scientific articles searched in LILACS, SciELO, and PubMed. We also accessed documents such as guidance, leaflets, surveys, and protocols published by the Brazilian IBD Program/Ministry of Health (MoH). The topics analyzed were mainly related to the implementation of a national registry, procurement of CFC and procoagulants, incorporation of new technologies, and education of caregivers, patients, and their families. We consider that the challenges and strategies used to implement the Brazilian program could contribute to the qualification of IBD care in other regions sharing similar socioeconomic characteristics.

Brief description of the Brazilian national health system

Brazil is the largest country in South America, with a territory of ∼8 515 767 km2 (area equivalent to the contiguous territory of the United States), distributed into 5 geographical regions, which comprises 26 states and a Federal District. The estimated Brazilian population in 2024 was 212 583 750 inhabitants.9 According to the World Bank, the Brazilian growth domestic product per capita was US $9564.58 in 2024, which classifies the economy as upper- to middle-income.

In Brazil, ∼70% of the population relies exclusively on the National Unified Health System (Sistema Único de Saúde [SUS]) for health care.10 The SUS is a government-funded, universal health care system that provides services to all citizens. It was instituted in 1988, and is known as the largest world health system financed by public budget (tax revenues and social contributions) at the federal, state, and municipal levels.

The implementation of an IBDs program in Brazil

Concomitant with the creation of SUS in the 1980s, public blood centers were instituted in the state capitals for the collection, processing, and distribution of blood, as well as to serve as reference centers for the management of patients with IBDs.11,12 At that time, IBDs were mainly represented by hemophilia, and treatment was based on cryoprecipitate and fresh frozen plasma.13 In the early 1990s, the SUS initiated the importation of small quantities of factor VIII concentrates, which were distributed to the coordinating blood centers located at the capitals of the states. At that time, the procurement of CFC occurred irregularly, and the distribution criteria were not well defined.14 In 1994, the MoH established a program that improved and organized the distribution of CFC to the coordinating blood centers, which distributed the CFC to the hemophilia treatment centers (HTCs). By that time, a technical advisory committee composed of 5 experts in the field of bleeding disorders was set up. This consultive and voluntary committee, which is still active, supports the preparation of guidance, treatment protocols, and educational documents, and actively participates in educational activities. Upon the incrementation of the purchase of CFC in the early 2000, the use of cryoprecipitate became prohibited for the treatment of people with hemophilia and VWD in 2002 (Figure 1).15

Timeline of the main policies instituted in the Brazilian program of IBDs. Timeline of the key incorporation of therapies for hemophilia and allied disorders by the national public health care program in Brazil. FFP, fresh frozen plasma.

Timeline of the main policies instituted in the Brazilian program of IBDs. Timeline of the key incorporation of therapies for hemophilia and allied disorders by the national public health care program in Brazil. FFP, fresh frozen plasma.

Until 2003, the main role of the IBD program relied on the central procurement and distribution of CFCs to the HTCs. There was scarce and faulty information on the number of patients with IBDs, and a registry was not available. Home treatment for hemophilia was slowly instituted due to insufficient quantities of CFC purchased. Then, in 2000, a “one dose program” of factor VIII or IX was instituted for home infusion in case of bleeding. The quantity delivered should be sufficient to elevate the level of deficient factor to 30% to 40%.16 After infusion, the patient should seek consultation at the HTC for evaluation of bleeding severity and need for completion of treatment. In 2004, a formal program on IBDs was established, which was composed of dedicated staff to address the routine activities of the program, and a consultant/advisor or expert in the field of thrombosis and hemostasis. In 2007, due to some increment of the quantities of CFC purchased, the number of home doses increased to 3.17 This supported the home treatment of most mild/moderate bleeding, mainly joint bleeding. This was an important step forward in the improvement of hemophilia care, and assured the prompt treatment of most bleeding events without the need to seek care in the HTC. However, home treatment only became a full program in 2012, upon the procurement of large quantities of factor VIII concentrate through a technology transfer agreement between HEMOBRAS (a Brazilian manufacturer of blood products and biotechnology) and Baxter (now, Takeda). This supported the implementation of several actions in hemophilia A care. Regarding hemophilia B, the procurement of factor IX concentrate continued to take place through tenders. Currently, there are 32 comprehensive hemophilia treatment centers (CHTC) in Brazil (1 in each of the 25 state capitals, except São Paulo which has 6, and 1 in the Federal District) and 150 HTCs. Factor concentrates/procoagulants are made available to patients or their parents by the HTCs every 1 to 2 months, upon medical prescription. There is no delivery of factor concentrates/procoagulants to the patients’ home, except in the CHTC of the Federal District.

Hemophilia prophylaxis was instituted in Brazil in 2011 to patients with hemophilia A and B with factor levels <0.02 IU/dL.16 The protocol recommends 25 IU/kg of factor concentrate 2 to 3 times weekly, with 5 IU/kg per dose increment in case of bleeding, reaching a maximum of 50 IU/kg per dose.16 Immune tolerance induction (ITI) was implemented in 2012 to patients with hemophilia A who required bypassing agents (activated prothrombin complex and/or recombinant factor VII activated concentrates) to treat or prevent bleeding.18 The protocol is based on a low-dose ITI regimen, that is, 50 IU/kg of factor VIII concentrate 3 times weekly. The dose can be increased to 100 IU/kg in case there is no decay of inhibitor of at least 20% after 3 months of maximum inhibitor peak.18

Between 2007 and 2011, an increased budget to the IBD program supported the expansion of the portfolio and quantities of products to treat other IBDs19 (Figures 1 and 2). A list of products currently purchased is detailed in Table 1.

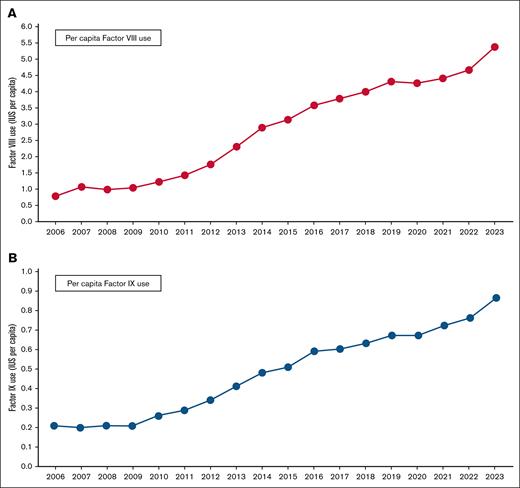

Per capita use of factor VIII and factor IX concentrates in Brazil from 2006 to 2023. Per capita use of (A) factor VIII and (B) factor IX in Brazil from 2006 to 2023, in international units. Data relate to recombinant and plasma-derived factors. Adapted from the annual reports of the Brazilian MoH.20

Per capita use of factor VIII and factor IX concentrates in Brazil from 2006 to 2023. Per capita use of (A) factor VIII and (B) factor IX in Brazil from 2006 to 2023, in international units. Data relate to recombinant and plasma-derived factors. Adapted from the annual reports of the Brazilian MoH.20

In 2024, the budget for the MoH was 266 billion Brazilian reais (∼50 billion US dollars), whereas the budget for the IBD program was ∼1.5 billion Brazilian reais (∼300 million US dollars), which is mostly (>90%) used for the procurement of factor concentrates/procoagulants. This represents ∼0.6% of the budget of the MoH.

The satisfaction with the IBD program in Brazil was evaluated by a survey performed in 2011 with 367 patients with hemophilia, from all Brazilian states. A total of 88% of patients reported satisfaction with care provided by their HTCs.21

First and foremost, data: implementation of a national registry

In Brazil, the National Program on IBDs is also responsible for registering patients and monitoring treatment and relevant outcomes, such as complications of the diseases (eg, inhibitor development, blood-transmitted infections, allergic reactions, and others).

Until 2002, there was scarce and faulty information on the number of patients with IBDs, and a formal registry was not available. The registration of patients was performed by the states on excel spreadsheets and sent to the MoH. The registry had several inconsistencies, such as incomplete data, duplication, and underreporting of patients.22 Therefore, there was an urgent need to develop a national registry capable of collecting reliable data and to monitor the use of CFC, which were the main objectives of its conception at that time.

In 2009, the MoH funded the development of a national, web-based registry named HemovidaWeb Coagulopatias. The registry was developed in collaboration with DATASUS (Departamento de Informação e Informática do Sistema Único de Saúde). The database was developed in PHP 5.0 language and is available on the internet at http://coagulopatiasweb.datasus.gov.br. It contains several modules, designed to collect sociodemographic, clinical, laboratory, and treatment data of patients with IBDs. Later, a stock control module was also added to support the management and monitoring of CFC and procoagulants. The staff at HTCs enter the information in the system, which is captured by the MoH, in real time. All new patients entering in the registry nationally are validated by a designated staff, on a daily basis. For detailed reports of the registry and its development, refer to Rezende et al23 and Barca et al.24

In the first months following the implementation of HemovidaWeb Coagulopatias, the number of registered patients with all forms of IBDs incremented by 30%, rising from 11 040 patients in December 2007, when the registrations were still performed in Excel spreadsheets, to 14 436 patients in December 2009.23 From December 2007 to December 2014, there was ∼90% increase in the registration of patients with all forms of IBD (from 11 040 to 21 066), respectively.23 The successful implementation of this registry has positioned Brazil as the fourth largest world population of patients with hemophilia, and the third largest of patients with VWD, according to the 2023 World Global Survey of the World Federation of Hemophilia.7 According to the last report of the IBDs program, in 2023, there were ∼32 000 people with IBDs in Brazil, of whom 11 618 and 2277 with hemophilia A and B, respectively, 11 375 with VWD, and 3554 with rare IBDs registered in the HemovidaWeb Coagulopatias.25 Women and girls who are potential carriers of hemophilia are investigated through assessment of factor levels; the ones with a bleeding phenotype are reported in the registry and receive treatment.

The implementation of HemovidaWeb Coagulopatias not only promoted the registration of previously unreported patients, but also supported the acquisition of relevant and reliable data for the procurement of CFC and procoagulant, helping policy-makers on planning IBDs care in Brazil. It also allowed the collection of incident cases of IBDs, inhibitors, and other complications, as well as to monitor the treatment use by each patient in real-time. Of note, to be qualified for treatment, registration of people with IBDs is compulsory in the HemovidaWeb Coagulopatias.

Centralizing the procurement of procoagulants for IBDs

One of the key elements for setting up a program on IBDs involves the procurement of CFC and other procoagulants. Because this is the most expressive expenditure in IBDs care, representing ∼90% of all direct costs,26 strategies focusing on cost mitigation in combination with keeping up the high quality of the products purchased should be pursued.

In Brazil, central procurement through tenders was instituted in 2002 at municipal, state, and federal levels for the purchase of medicine and other goods, including the procurement of CFC and procoagulants. In 2004, driven by the need for more transparent and competitive tenders for CFC procurement, the process was modified to an “upside-down” bidding process (known as Pregão), in which the winner was the manufacturer offering the lowest price.27 After the implementation of Pregão, the prices of factor VIII and IX concentrates dropped to ∼40% below the prices practiced in the year before.27 Later, the system was further improved by changing in-person tenders to electronic Pregão, which was broadcast in real-time on the internet. To our knowledge, this procurement system of CFC practiced in Brazil was the first central tendering process ever described, after which other countries, such as Ireland and United Kingdom, followed.28

Following the procurement of CFC and procoagulants, the MoH distributes these products to the coordinating HTCs located in the states. The quantity of products sent to each of the 26 states and the Federal District depends on the population of patients with IBDs registered in each state, data provided by the HemovidaWeb Coagulopatias National Registry. Any patient with IBDs registered in the HTCs can be treated with CFC and/or procoagulants purchased by the MoH, even if they are covered by a private health insurance, which is the case for ∼20% of the Brazilian population. Therefore, we hypothesize that nearly all people with hemophilia and severe IBDs in Brazil are treated in the SUS. Although numbers are not available, people with mild IBD are also treated in private clinics. However, most of them are registered in the HemovidaWeb Coagulopatias, just in case they need treatment with CFC and/or procoagulants through life.

Following the improvement in the procurement process, the IBDs program focused on the expansion of the portfolio of CFCs and procoagulants (Table 1), as well as the increment of quantities purchased. As a result, we observed a rise in the international units per capita of factor VIII and IX concentrates used from 0.79 and 0.21 in 2006 to 5.38 and 0.86 in 2023, respectively (Figure 2).

Improving health outcomes of IBDs through implementation of public policies

Accessing health outcomes in public policies such as IBDs is of utmost relevance due to the high expenditures involved and to evaluate the implemented policies. However, few studies have explored health outcomes on IBD care in Brazil,29 and even fewer have compared outcomes before and after the implementation of actions such as prophylaxis and ITI.30

Fernandes et al retrospectively compared the incidence of central and peripheral nervous system disorders caused by bleeding in people with hemophilia in 1 center from 1992 to 2018, before and after the introduction of prophylaxis (2011). They found that 5 events occurred in patients without prophylactic treatment, whereas none occurred in the ones under prophylaxis (5/20 vs 0/29, P = .0081), respectively, from 2011 to 2018.29 Nascimento et al, in a single-center, cross-sectional study, evaluated 133 patients with hemophilia (89% hemophilia A) who were under prophylaxis (16% under primary prophylaxis) for 5 to 10 years, and showed that ∼67% of the patients presented no joint bleeding during 2021.31

Our group has evaluated the mortality of people with hemophilia A and B in Brazil from 2000 to 2014, and found that mortality was 13% higher when compared with the general male population.32 The main cause of death was bleeding (32.4%), of which about half was related to intracranial hemorrhage. The total number of deaths due to HIV decreased over the years, contrasting with an increase in deaths due to cancer and cardiovascular disease. Interestingly, the mortality rates reduced from 2007, which we attributed to a possible contribution of the “three-doses” scheme of home treatment. This study clearly showed a reduced mortality of hemophilia in Brazil across the years analyzed, likely reflecting the improvement in hemophilia care. Santo et al33 also evaluated causes of death and mortality trends related to hemophilia in Brazil from 1999 to 2016, reporting similar findings as our study.32

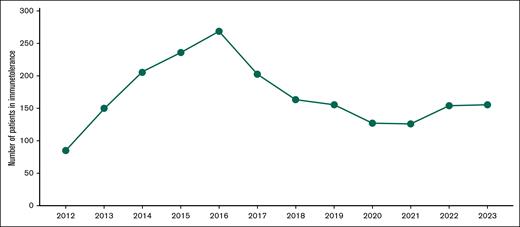

To date, ∼600 patients with hemophilia A have been treated with ITI in Brazil. Within 4 years of the implementation of ITI, ∼300 people with hemophilia A and inhibitors were included (Figure 3). One study of our group, while evaluating the effectiveness of the Brazilian ITI protocol of low doses (50 IU factor VIII concentrate 3 times weekly) in 142 patients with hemophilia A and high-responding inhibitors, reported a response rate of ∼70%.34 This likely resulted in the robust reduction in the prevalence of anti-factor VIII antibodies (inhibitors) in people with hemophilia A after the implementation of ITI in 2012, dropping from 8.3% in 2010 to 3.2% in 2022.35,36 However, it is important to highlight that the quantification of inhibitors was not available for a high proportion of patients (29% in 2010 and 18% in 2022).34,35

Patients with hemophilia A under ITI therapy from 2013 to 2023. The graph shows the number of patients formally registered in the ITI treatment per year. Adapted from the annual reports of the Brazilian MoH.37

Patients with hemophilia A under ITI therapy from 2013 to 2023. The graph shows the number of patients formally registered in the ITI treatment per year. Adapted from the annual reports of the Brazilian MoH.37

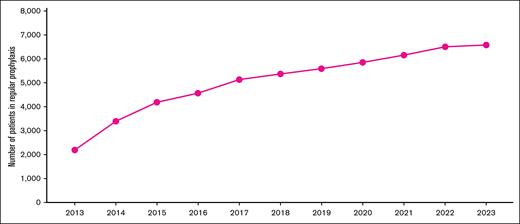

Regarding hemophilia prophylaxis, in 2023, ∼7000 people with hemophilia A and B were under prophylaxis in Brazil, according to the last administrative report from the MoH25 (Figure 4).

Patients with hemophilia A and B under regular prophylaxis according to the national registry from 2017 to 2023. The graph shows the number of patients with hemophilia A and B formally registered in long-term prophylaxis per year. Adapted from the annual reports of the Brazilian MoH.37

Patients with hemophilia A and B under regular prophylaxis according to the national registry from 2017 to 2023. The graph shows the number of patients with hemophilia A and B formally registered in long-term prophylaxis per year. Adapted from the annual reports of the Brazilian MoH.37

HTA for new therapies in IBDs

In Brazil, the incorporation of new therapies in the SUS is an attribution of the MoH. Since 2011, the decision to incorporate any new treatment is based on a formal health technology assessment (HTA) study, followed by a standardized process involving several stakeholders, under the coordination of the MoH.38 Considering that SUS is the exclusive health care provider for ∼150 million Brazilians,10,39 high stakes are involved in these decisions. This is particularly true in the field of hemophilia, as virtually 100% of patients diagnosed in Brazil rely on this public system to obtain their treatment, coupled with the high and increasing costs of hemophilia treatment.40 Despite that, the Brazilian National Program of IBDs has been able to incorporate new technologies, keeping the program updated when compared with other countries of similar income level (Figure 1).

The HTA process that subsidizes incorporation decisions is centralized at CONITEC, a government agency whose attribution is to incorporate, exclude, or modify health technologies by SUS, as well as to establish or revise clinical protocols or therapeutic guidelines.26 Any organization, whether private or public, patient association, or even an individual can submit a request to CONITEC, following a predefined guidance. The submitted documents then enter a formal HTA analysis composed of the following domains: clinical, economic, patient-perspective, and organizational.

Until 2024, the economic domain included cost-effectiveness, opportunity cost, and impact on the national budget. However, it has recently incorporated cost-effectiveness thresholds as possible additional criteria.41 Of note, although the guidance incorporating these thresholds as part of the HTA process clearly states that they should not be used as the only parameter to exclude the incorporation of health technologies, the most recent HTA discussion held by CONITEC in the field of hemophilia calculated and discussed these thresholds during the deliberation process. Since its creation in 2011, CONITEC has evaluated 11 submissions of new hemophilia therapies, of which 5 were incorporated and 1 is still under analysis. The discussions about incorporation at CONITEC involve stakeholders such as the MoH, other government agencies, national medical and scientific associations, as well as patient representatives. A preliminary decision is then submitted to public consultation, whose inputs are presented to CONITEC for a final decision. The public participation in these consultations is considerable and represents a positive aspect of the process. The last incorporation of a new therapy of interest to the IBD program by CONITEC occurred in 2023, and consisted of the expansion of the use of emicizumab to all patients with hemophilia A and an inhibitor.42 It received >600 inputs from citizens and organizations, which were individually analyzed and addressed as part of the decision process.

Due to the characteristics of the Brazilian program, a positive decision to incorporate a treatment imposes immediate (within 180 days) country-wide free access to the incorporated technology, that requires not only a new budget, but also solutions to purchase and distribute the new technology to all HTCs. Accordingly, 1 would expect that decisions need to accommodate the urgency and pressure (from both health care professionals and patients) to offer new treatments already available in higher-income countries, as well as the limitations imposed by a finite health budget and the need for novel logistic solutions. To date, the system described has been capable of providing a reasonable portfolio of new treatments to >30 000 patients with IBDs, even though some treatment modalities available in high-income countries are not yet offered by SUS (Table 1). An illustrative example is the fact that at the time of this article being written, in Brazil, prophylaxis is offered for all people with hemophilia with an indication thereof. However, this is based on emicizumab for people with hemophilia A and inhibitors, and on factor VIII concentrate for the ones without inhibitors. Furthermore, we foresee major challenges to the incorporation of newer technologies such as gene and nonfactor therapies, due to their high costs and complexities to be implemented.

Among the strengths of the system, that possibly contribute to these results, is the already mentioned strategy of central procurement of CFC and procoagulants, as well as the fact that the system has always welcomed and considered open and frank discussions involving government representatives, the scientific community, patient associations, and the pharmaceutical industry.

Education of patients, health care workers, and providers

The importance of education for health care professionals involved in IBD care has been long recognized as 1 of the cornerstones of any system or program that intends to provide high-quality care for this population.43-45 In addition, educational needs should also involve patients, their families, and caregivers. Accordingly, 1 of the main initiatives of the Brazilian National Program was the establishment of a diverse range of educational initiatives targeting multidisciplinary teams, patients, and families.

These initiatives involved 3 main strategies. The first consisted of holding in-person educational events for professionals from multidisciplinary teams focused on critical aspects of care for these patients, such as laboratory diagnosis, integrated care in multidisciplinary teams, and prevention and treatment of complications. Until the COVID-19 pandemic, these events also represented an opportunity to form and consolidate “communities of practice”46 that amplified the impact of these trainings during the intervals between these activities. After the pandemic, these trainings were replaced by virtual activities that, although capable of qualifying the teams, they have, in our view, limited potential for encountering and establishing networking, which have been shown to improve health care.37 This recent transition from in-person to virtual training strategies has generated a negative perception among members of the community, the impact of which is not yet clear.

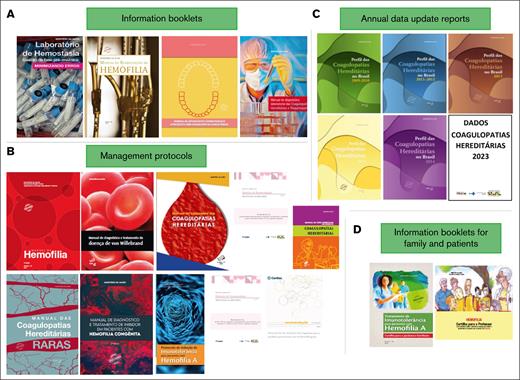

The second line of action consisted of producing a series of guidance on diagnosis and treatment, as well as leaflets addressing various aspects of IBD care for patients, families, and schools (Figure 5). These documents were produced with the contribution of professionals from the HTCs and the National Technical Committee on IBDs, who also actively engaged in their dissemination.

Educational documents available for health care professionals, patients, and families. Educational documents were produced and provided by the Brazilian IBD program, and include (A) booklets about different aspects of IBD care for health care professionals, (B) guidance and treatment protocols, (C) annual data reports about the IBD, and (D) booklets and leaflets with information for patients and family members, among others.

Educational documents available for health care professionals, patients, and families. Educational documents were produced and provided by the Brazilian IBD program, and include (A) booklets about different aspects of IBD care for health care professionals, (B) guidance and treatment protocols, (C) annual data reports about the IBD, and (D) booklets and leaflets with information for patients and family members, among others.

Finally, the third strategy consisted of working in collaboration with patient associations such as the Brazilian Federation of Hemophilia, among others, with the aim of providing information to patients and their families. This was done through the regular participation of the MoH team in events organized by these associations, in addition to open dialog with their representatives and their representation at the National Technical Committee on IBDs. Together, these initiatives fostered the integration of the HTCs and the IBDs program, contributing to improvement of patient care.

Challenges of the Brazilian program of IBDs

One of the main challenges of a national IBD program is to assure incorporation of a growing number of therapeutic innovations, while maintaining its financial sustainability, which is needed for the equitable and universal provision of health care for all. This is particularly relevant as it is one of the pillars of the Brazilian SUS. Although the pace of innovations in hemophilia treatment poses a challenge for any country, this has been specially challenging in Brazil, due to the large population of IBD and to budget constraints. Therefore, one of the strategies of the Brazilian government has been to invest in the national capacity to fractionate plasma-derived factors and to produce recombinant factor VIII by HEMOBRAS. Although this strategy has been able to ensure a safe and reliable supply of these products for the IBD population, it poses a huge pressure on the program when novel, sometimes disruptive, technologies are launched. This is the case with extended half-life factor concentrates, nonfactor replacement therapies, gene therapy, among others. Indeed, to date, finding the “sweet spot” between establishing a national manufacturer that offers an independent supply of CFC, and allowing the incorporation of new technologies has not yet been achieved.

Another challenge refers to the monitoring of outcome measures. Currently, the national registry does not measure outcomes such as musculoskeletal complications, bleeding rates, adherence to treatment, or quality of life, which are key elements to access the efficiency of a health policy. Furthermore, the registry collects few follow-up data, currently limited to inhibitor titers and treatment data.

Lastly, Brazil is a continental country with huge inequalities. Some CHTCs/HTCs have a modern infrastructure with highly skilled professionals, whereas others lack laboratory facilities and trained professionals. Moreover, education of patients and families is a major issue, a significative proportion of the patients belong to a low socioeconomic background with few years in formal education.

Conclusion

The implementation of IBDs programs in less-resourced countries is a challenge due to complex diagnosis and treatment, high costs involved, and need of a qualified multiprofessional team. Here, we described the implementation of a successful public health policy in IBD in a lower- to middle-income country. We believe that the strategies used to implement our program may be useful for other countries with similar economies to establish their own program.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all the previous coordinators of the Coordination of Blood and Blood Products of the Ministry of Health, the staff of the Inherited Bleeding Disorders Program and Information Unit, the staff of DATASUS and of the Hemophilia Treatment Centers, and the members of the National Advisory Committee of Inherited Bleeding Disorders Program.

Authorship

Contribution: S.M.R. designed the content of the manuscript, analyzed the data, and wrote the paper; E.V.D.P. analyzed the data and wrote the paper; and both authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: S.M.R. has served as an advisor to the National Program on Inherited Bleeding Disorders from 2004 to 2021; has received consultant fees from the Brazilian MoH; and has been a member of the Committee on Inherited Bleeding Disorders of the Brazilian MoH since 2004. E.V.D.P. has served as an advisor to the National Program on Inherited Bleeding Disorders from 2022 to 2025; has received consultant fees from the Brazilian MoH; has served as a speaker in a Novo Nordisk–sponsored event in 2025; and has been a member of the Committee on Inherited Bleeding Disorders of the Brazilian MoH since 2022.

Correspondence: Suely M. Rezende, Department of Internal Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, 190 Ave Alfredo Balena, Room 255, Belo Horizonte 30130-100, Brazil; email: suely.rezende@uol.com.br.