Key Points

Outpatient low-dose VenAza combined with itraconazole reduced early mortality and hospitalizations while maintaining treatment efficacy.

VenAza offers a safer, cost-effective alternative to intensive chemotherapy for newly diagnosed AML.

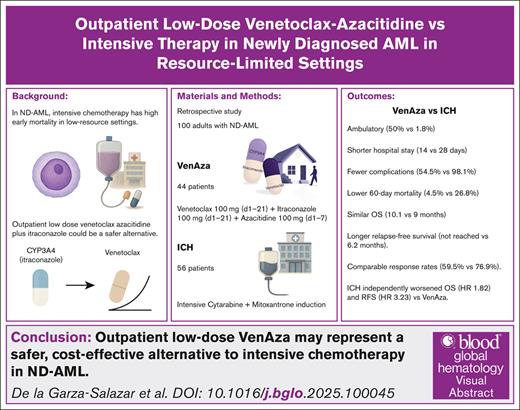

Visual Abstract

Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) treatment in fit adults relies on intensive chemotherapy, but limited access to supportive care and inpatient capacity limits constrains its feasibility in low-resource settings. Venetoclax, a B-cell lymphoma 2 inhibitor, has shown promise in unfit patients with AML, but its role in induction-eligible adults remains unclear. We retrospectively compared an outpatient regimen combining low-dose venetoclax, itraconazole, and azacitidine (VenAza) with intensive chemotherapy in 100 adults with newly diagnosed AML. Forty-four received low-dose VenAza and 56 received intensive therapy. The VenAza group had significantly less febrile neutropenia rates (50% vs 90.6%; P = .0001). Half of the VenAza group remained ambulatory during induction (50% vs 1.8%; P = .0001), had shorter hospital stays (median, 14 vs 28 days; P = .0001), and reduced 60-day mortality (4.5% vs 26.8%; P = .003). Response rates were comparable (59.5% vs 76.9%; P = .10), whereas relapse-free survival was significantly longer with VenAza (not reached vs 6.2 months; P = .017). The incidence of relapse was also lower (P = .002). VenAza showed similar overall survival (10.1 vs 9.0 months; P = .097). Landmark and Cox analyses confirmed these findings, with VenAza independently associated with improved overall survival (hazard ratio [HR], 1.82; P = .039) and relapse-free survival (HR, 3.23; P = .043). Outpatient use of VenAza reduced hospitalizations, early deaths, and complications, while maintaining efficacy. This strategy may represent a safer, cost-effective alternative to intensive chemotherapy for induction-eligible patients with AML in low-resource settings, potentially informing global practice where supportive care is limited.

Introduction

Intensive chemotherapy (ICH) with 7+3 remains the cornerstone for newly diagnosed acute myeloid leukemia (ND-AML).1 Venetoclax, a potent B-cell lymphoma 2 inhibitor, is now standard for patients unfit for receiving ICH,2 but evidence in fit patients with ND-AML eligible for ICH remains scarce.

The cost of venetoclax can reach tens of thousands of dollars per cycle.3 However, because venetoclax is metabolized by cytochrome P450 3A4 (CYP3A4), coadministration with itraconazole increases plasma exposure and reduces costs by 75%.4,5 Our phase 2 trial showed that outpatient low-dose venetoclax combined with itraconazole and azacitidine is feasible, well tolerated, and achieves comparable remission rates, with most patients completing the first cycle without hospitalization and short stays among those admitted.6

In low-income settings, ICH induction poses a greater risk because of higher early mortality rates, limited access to supportive care, and increased infectious complications.7 These challenges highlight the need for alternative induction regimens that are both effective and feasible in outpatient settings. Therefore, we hypothesized that outpatient-based induction with low-dose venetoclax, itraconazole, and azacitidine (VenAza) could provide a safer yet equally effective alternative to ICH.

In this study, we retrospectively analyzed and compared the safety and efficacy of outpatient-based induction with low-dose VenAza with intensive induction with cytarabine and anthracycline in patients with ND-AML eligible for ICH. Through this approach, we aimed to generate valuable insights into the benefits and risks of this alternative regimen, potentially providing a more cost-effective and well-tolerated alternative for patients with ND-AML.

Methods

We retrospectively collected data from all consecutive patients diagnosed with ND-AML who received treatment between August 2016 and March 2023. Until September 2021, patients underwent ICH induction; thereafter, our institution adopted outpatient-based low-dose VenAza as an alternative induction regimen regardless of patient fitness.6 The study included 100 adult patients aged 18 years or older who met the 2016 World Health Organization criteria for nonpromyelocytic AML, confirmed according to EuroFlow guidelines.8 Cytogenetic risk was assessed using bone marrow karyotyping with G-banding, complemented by molecular testing when available. Patients with secondary AML were also included, without restrictions based on eligibility for hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT).

Induction therapy

In the low-dose VenAza group, induction consisted of up to 2, 21-day cycles with outpatient venetoclax (100 mg orally, once daily, days 1-21) and azacitidine (fixed dose 100 mg subcutaneously, once daily, days 1-7). Itraconazole (100 mg twice daily, days 1-21) was coadministered to enhance cost-effectiveness, irrespective of neutrophil count. Cycle number depended on response and patient condition. After each cycle, therapy was paused ≤14 days for hematologic recovery, without G-CSF support. A >50% blast reduction qualified for a second cycle; absence of reduction indicated refractory disease.

Patients who received ICH received 5 or 7 days of intermediate-dose cytarabine (200 mg once daily as a 20-hour infusion) and 3 consecutive days of IV mitoxantrone (10 mg/m2 per day).

Consolidation therapies

Consolidation therapy strategies were recorded for all patients and varied according to response and resources available. Treatment included continued VenAza for patients in and/or intermediate dose cytarabine and HSCT when applicable and accessible as all consolidation treatments required out-of-pocket payments.

Supportive care

Patients with a white blood cell count >50 × 109/L received cytoreductive therapy according to the NCT05062278 protocol, with either oral hydroxyurea (50 mg/m2 once daily) or a single IV dose of vinblastine (10 mg), together with fluid replacement and allopurinol for tumor lysis syndrome prophylaxis.9 Ramp-up dosing of venetoclax was not implemented, as only 100 mg tablets were available and were not fragmented because of stability concerns. Patients with severe neutropenia received prophylactic levofloxacin, acyclovir, and trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole.

In the VenAza group, follow-up assessments were conducted at an outpatient center. Hospitalization criteria included organ dysfunction (modified Marshall score ≥2), neutropenic fever, sepsis, hypotension (<90/60 mmHg), oxygen saturation <95%, tumor lysis syndrome, leukostasis, and hyperleukocytosis (white blood cell count >100 × 109/L), as previously outlined. Hospitalized patients were discharged once they achieved adequate fluid balance, tolerated oral intake, completed de-escalation from parenteral to oral antibiotics, remained afebrile, and maintained stable vital signs for at least 72 hours.

Outcomes and definitions

The primary outcomes of the study were to assess the safety and efficacy of outpatient VenAza compared with ICH. Safety parameters included early mortality, rates of complications, neutropenic fever, hospitalization rates, and length of hospital stay.

Measurable residual disease (MRD) was assessed by 8-color flow cytometry (BD FACSCanto II, sensitivity 10−3 -10−4) following EuroFlow guidelines,8 evaluated after hematologic recovery or within 14 days. Responses followed 2017 European Leukemia Net (ELN) criteria (complete remission [CR], CR with incomplete count recovery [Cri], CR with partial hematologic recovery, morphologic leukemia-free state; partial response [PR] ≥50% blast reduction).10 Relapse was defined per ELN as ≥5% blasts, blood/extramedullary disease, or reappearance of MRD (cutoff ≥0.01%).10

The secondary objectives examined long-term outcomes, including relapse rates, relapse-free survival (RFS), event-free survival (EFS), mortality rates, and overall survival (OS). Induction mortality was defined as death within the first 60 days of initiating ICH. Adverse events were classified according to the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (version 5.0).

Sample size calculation

Sample size calculation was performed using G∗Power software (version 3.1.9.6). To detect a difference in complication rates, we assumed an 80% complication rate in the ICH group, with the goal of reducing it to 50% in the VenAza group. A 1-tailed Fisher exact test was applied, assuming a lower complication rate in the VenAza group. The final sample size included 56 patients in the intensive chemotherapy group and 44 in the VenAza group, providing 90% power at a 5% type I error rate (alpha).

Statistical analysis

The normality of continuous variables was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test. Categorical variables were compared using the χ2 test, whereas continuous variables were analyzed with the Mann-Whitney U test. Median follow-up was estimated by the reverse Kaplan-Meier method.

Survival analyses (OS, EFS, and RFS) were performed using the Kaplan-Meier method. OS, EFS, and RFS were analyzed by Kaplan-Meier with landmarking for early deaths (≤60 days) and censoring at HSCT. Cox models adjusted for age, secondary AML, and cytogenetic risk. Subgroup analyses were prespecified (cytogenetic risk, HSCT status), with Bonferroni correction for selected comparisons (eg, causes of death). To limit type I error in this modest cohort, log-rank testing was restricted to medians, whereas 24- and 36-month outcomes were descriptive.

Competing risks for mortality and relapse were assessed by cumulative incidence functions using the Fine-Gray model, and Gray’s test compared groups.

Analyses were performed in SPSS version 27 and R studio (2022.07.0) with “survival,” “survminer,” “cmprsk,” and “ggplot2” packages.11 All tests were 2-tailed, with P < .05 considered significant.

This retrospective comparative study received approval from our institutional review board and adhered to the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki.

Results

Patient characteristics

A total of 100 patients were included, 44 (44%) treated with VenAza plus itraconazole and 56 (56%) with ICH. Half were female (54%), and all had Eastern Cooperative Group (ECOG) score ≤2 (Table 1). Cytogenetic risk was available in 67 patients, with 29.9% classified as adverse. Most had de novo AML (81%), whereas secondary AML (from myeloproliferative neoplasm, myelodysplastic syndrome, or chronic myelomonocytic leukemia) was more common in the VenAza group (P < .001). Compared with ICH, the VenAza cohort was older (median, 52 vs 40 years; P = .018) and had more adverse cytogenetics (43.3% vs 18.9%; P = .03). The ICH group showed higher leukocyte counts (47.1 ×109/L vs 8.6 ×109/L; P = .001), though cytoreduction rates were similar (42.9% vs 31.8%; P = .26).

Baseline demographic, disease, and pretreatment characteristics according to induction strategy

| . | Total (N = 100) . | VenAza (n = 44) . | ICH (n = 56) . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||||

| Age, median (range) | 46 (18-78) | 52 (18-78) | 40 (18-73) | .018 |

| Male, n (%) | 46 (46) | 19 (43.2) | 27 (48.2) | .62 |

| ECOG, n (%) | .034 | |||

| 0 | 4 (4) | 4 (9.1) | 0 (0) | |

| 1 | 53 (53) | 25 (56.8) | 28 (50) | |

| 2 | 43 (43) | 15 (34.1) | 28 (50) | |

| Disease characteristics | ||||

| Diagnosis, n (%) | ||||

| De novo∗ | 81 (81) | 27 (61.4) | 54 (96.4) | .0001 |

| MPN∗ | 3 (3) | 3 (6.8) | 0 (0) | |

| MDS∗ | 10 (10) | 9 (20.5) | 1 (1.8) | |

| CMML∗ | 6 (6) | 5 (11.4) | 1 (1.8) | |

| Monocytic features (n = 90), n (%) | 35 (38.9) | 12 (27.9) | 23 (48.9) | .041 |

| ELN 2017 (n = 67), n (%) | .03 | |||

| Non adverse | 47 (70.1) | 17 (56.7) | 30 (81.1) | |

| Adverse∗ | 20 (29.9) | 13 (43.3) | 7 (18.9) | |

| Laboratory values at diagnosis, median (range) | ||||

| Hemoglobin, g/dL | 7 (2.2-13.8) | 7.3 (4.4-11.6) | 6.6 (2.2-13.8) | .155 |

| Leukocytes, 1 × 109/L | 27 (0.6-404) | 8.6 (0.6-372) | 47.1 (0.9-404) | .001 |

| Platelets, 1 × 109/L | 32.7 (2-373) | 34.5 (5-373) | 30.3 (2-196) | 4 |

| Treatment-related variables | ||||

| Cytoreduction, n (%) | 38 (38) | 14 (31.8) | 24 (42.9) | .26 |

| Number of cycles, n (%) | .0001 | |||

| 1 | 75 (75) | 24 (54.5) | 51 (91.1) | |

| 2 | 25 (25) | 20 (45.5) | 5 (8.9) | |

| Days to treatment, median (range) | 5 (0-120) | 7 (0-120) | 4 (0-16) | .006 |

| . | Total (N = 100) . | VenAza (n = 44) . | ICH (n = 56) . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||||

| Age, median (range) | 46 (18-78) | 52 (18-78) | 40 (18-73) | .018 |

| Male, n (%) | 46 (46) | 19 (43.2) | 27 (48.2) | .62 |

| ECOG, n (%) | .034 | |||

| 0 | 4 (4) | 4 (9.1) | 0 (0) | |

| 1 | 53 (53) | 25 (56.8) | 28 (50) | |

| 2 | 43 (43) | 15 (34.1) | 28 (50) | |

| Disease characteristics | ||||

| Diagnosis, n (%) | ||||

| De novo∗ | 81 (81) | 27 (61.4) | 54 (96.4) | .0001 |

| MPN∗ | 3 (3) | 3 (6.8) | 0 (0) | |

| MDS∗ | 10 (10) | 9 (20.5) | 1 (1.8) | |

| CMML∗ | 6 (6) | 5 (11.4) | 1 (1.8) | |

| Monocytic features (n = 90), n (%) | 35 (38.9) | 12 (27.9) | 23 (48.9) | .041 |

| ELN 2017 (n = 67), n (%) | .03 | |||

| Non adverse | 47 (70.1) | 17 (56.7) | 30 (81.1) | |

| Adverse∗ | 20 (29.9) | 13 (43.3) | 7 (18.9) | |

| Laboratory values at diagnosis, median (range) | ||||

| Hemoglobin, g/dL | 7 (2.2-13.8) | 7.3 (4.4-11.6) | 6.6 (2.2-13.8) | .155 |

| Leukocytes, 1 × 109/L | 27 (0.6-404) | 8.6 (0.6-372) | 47.1 (0.9-404) | .001 |

| Platelets, 1 × 109/L | 32.7 (2-373) | 34.5 (5-373) | 30.3 (2-196) | 4 |

| Treatment-related variables | ||||

| Cytoreduction, n (%) | 38 (38) | 14 (31.8) | 24 (42.9) | .26 |

| Number of cycles, n (%) | .0001 | |||

| 1 | 75 (75) | 24 (54.5) | 51 (91.1) | |

| 2 | 25 (25) | 20 (45.5) | 5 (8.9) | |

| Days to treatment, median (range) | 5 (0-120) | 7 (0-120) | 4 (0-16) | .006 |

CMML, chronic myelomonocytic leukemia; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Group score; MPN, myeloproliferative neoplasm; MDS, myelodysplastic syndrome.

Bonferroni-adjusted post hoc analysis showed significant differences in this subgroup.

Induction therapy efficacy

In the VenAza group, patients received either 1 (24 patients, 54.5%) or 2 (20 patients, 45.5%) treatment cycles, whereas most patients in the ICH group underwent only 1 induction cycle (91.1%) (P = .0001). Time to treatment initiation was significantly longer in the VenAza group than in the ICH group (median, 7 vs 4 days; P = .006; Table 1). However, in multivariable analysis, time to treatment did not independently predict CR (supplemental Table 1).

The ELN response was significantly different between groups, with similar objective response rate (ORR) rates between VenAza and ICH (59.5% vs 76.9%; P = .1), and composite CR/ CR with partial hematologic recovery/CRi/ morphologic leukemia-free state response rates (56.8% vs 76.9%; P = .06, respectively).

Seventy-six patients were assessed for response, and 24 considered refractory to first-line treatment (31.6%), n = 15 treated with VenAza (40.5%) and 9 with ICH (23.1%).

Response could not be assessed in n = 24 (Table 2). A higher, though nonsignificant, proportion of MRD-negative responses were observed in the ICH group (61.9% vs 84.6%; P = .16).

Efficacy and early safety outcomes by treatment group

| . | Total (N = 100) . | VenAza (n = 44) . | ICH (n = 56) . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Efficacy outcomes | .01 | |||

| Response (ORR) (n = 76), n (%) | 52 (68.4) | 22 (59.5) | 30 (76.9) | .1 |

| Composite CR/CRh/CRi (n = 76), n (%) | 47 (61.8) | 17 (45.9) | 30 (76.9) | .005 |

| Composite CR/CRh/CRi/MLFS | 51 (67.1) | 21 (56.8) | 30 (76.9) | .06 |

| ELN response category (n = 76), n (%) | .01 | |||

| CR | 40 (52.6) | 12 (32.4) | 28 (71.8) | |

| CRh | 2 (2.6) | 2 (5.4) | 0 (0) | |

| CRi | 5 (6.6) | 3 (8.1) | 2 (5.1) | |

| MLFS | 4 (5.3) | 4 (10.8) | 0 (0) | |

| Partial response | 1 (1.3) | 1 (2.7) | 0 (0) | |

| No response | 24 (31.6) | 15 (40.5) | 9 (23.1) | |

| MRD status n (%) | .16 | |||

| Negative MRD | 24 (70.6) | 13 (61.9) | 11 (84.6) | |

| Positive MRD | 10 (29.4) | 8 (38.1) | 2 (15.4) | |

| Safety and early outcomes | ||||

| Hospitalization, n (%) | .0001 | |||

| Ambulatory | 23 (23) | 22 (50) | 1 (1.8) | |

| Hospitalization | 77 (77) | 22 (50) | 55 (98.2) | |

| Hospitalization, median (range), d | 25 (3-86) | 14 (5-65) | 28 (3-86) | .0001 |

| Complications (n = 98), n (%) | 77 (78.6) | 24 (54.5) | 53 (98.1) | .0001 |

| Neutropenic fever (n = 97), n (%) | 70 (72.2) | 22 (50) | 48 (90.6) | .0001 |

| Sepsis n (%) | 41 (41) | 17 (38.6) | 24 (42.9) | .67 |

| Bleeding (n = 97), n (%) | 8 (8.2) | 4 (9.1) | 4 (7.5) | .78 |

| . | Total (N = 100) . | VenAza (n = 44) . | ICH (n = 56) . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Efficacy outcomes | .01 | |||

| Response (ORR) (n = 76), n (%) | 52 (68.4) | 22 (59.5) | 30 (76.9) | .1 |

| Composite CR/CRh/CRi (n = 76), n (%) | 47 (61.8) | 17 (45.9) | 30 (76.9) | .005 |

| Composite CR/CRh/CRi/MLFS | 51 (67.1) | 21 (56.8) | 30 (76.9) | .06 |

| ELN response category (n = 76), n (%) | .01 | |||

| CR | 40 (52.6) | 12 (32.4) | 28 (71.8) | |

| CRh | 2 (2.6) | 2 (5.4) | 0 (0) | |

| CRi | 5 (6.6) | 3 (8.1) | 2 (5.1) | |

| MLFS | 4 (5.3) | 4 (10.8) | 0 (0) | |

| Partial response | 1 (1.3) | 1 (2.7) | 0 (0) | |

| No response | 24 (31.6) | 15 (40.5) | 9 (23.1) | |

| MRD status n (%) | .16 | |||

| Negative MRD | 24 (70.6) | 13 (61.9) | 11 (84.6) | |

| Positive MRD | 10 (29.4) | 8 (38.1) | 2 (15.4) | |

| Safety and early outcomes | ||||

| Hospitalization, n (%) | .0001 | |||

| Ambulatory | 23 (23) | 22 (50) | 1 (1.8) | |

| Hospitalization | 77 (77) | 22 (50) | 55 (98.2) | |

| Hospitalization, median (range), d | 25 (3-86) | 14 (5-65) | 28 (3-86) | .0001 |

| Complications (n = 98), n (%) | 77 (78.6) | 24 (54.5) | 53 (98.1) | .0001 |

| Neutropenic fever (n = 97), n (%) | 70 (72.2) | 22 (50) | 48 (90.6) | .0001 |

| Sepsis n (%) | 41 (41) | 17 (38.6) | 24 (42.9) | .67 |

| Bleeding (n = 97), n (%) | 8 (8.2) | 4 (9.1) | 4 (7.5) | .78 |

CRh, CR with partial hematologic recovery; MLFS, morphologic leukemia-free state.

Safety: hospitalizations, complications, and early outcomes

In the overall cohort, the hospitalization rate was 77%, with a median hospital stay of 25 days. Half of the patients in the VenAza group completed the induction regimen entirely on an outpatient basis. The VenAza group had significantly lower hospitalization rates compared to the ICH (50% vs 98.2%; P = .0001), and among those who required hospitalization, the median length of stay was shorter (14 days vs 28 days; P = .0001) (Table 2).

The overall incidence of complications, neutropenic fever, sepsis, and bleeding in the cohort was 78.6%, 72.2%, 41%, and 8.2%, respectively. No cases of tumor lysis syndrome were observed. The VenAza group had a significantly lower rate of complications (54.5% vs 98.1%; P = .0001), mainly because of a reduced incidence of neutropenic fever (50% vs 90.6%; P = .0001) (Table 2).

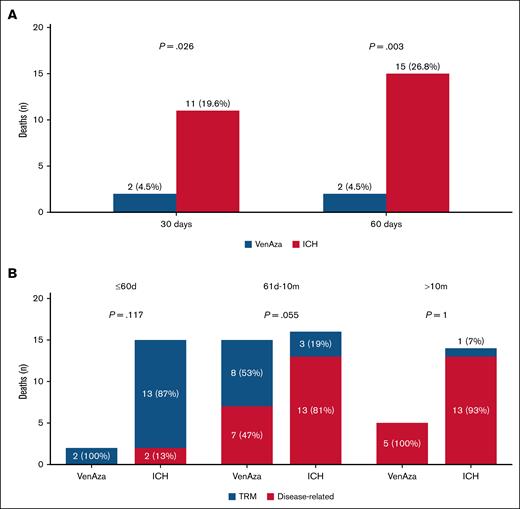

In the total cohort, early mortality at 30 and 60 days was 13% and 17.5%. VenAza was associated with significantly lower early mortality compared with ICH (30-day: 4.5% vs 19.6%; P = .026; 60-day: 4.5% vs 26.8%; P = .003) (Figure 1A). Within 60 days, deaths were mainly treatment-related in both groups (100% VenAza vs 87% ICH; P = .117). Between 61 days and 10 months, VenAza deaths were more evenly distributed (47% disease-related, 53% treatment-related) vs predominantly disease-related in ICH (81% vs 19%; P = .055). Beyond 10 months, nearly all deaths were disease-related (100% VenAza vs 93% ICH; P = 1.0) (Figure 1B).

Early mortality and causes of death stratified by time interval and treatment group. (A) Bar plots show the distribution of 30-day and 60-day mortality among patients treated with VenAza, blue or ICH, red. (B) Stacked bar plots show the distribution of treatment-related mortality (TRM, blue) and disease-related mortality (red) among patients treated with VenAza or ICH across 3 follow-up intervals.

Early mortality and causes of death stratified by time interval and treatment group. (A) Bar plots show the distribution of 30-day and 60-day mortality among patients treated with VenAza, blue or ICH, red. (B) Stacked bar plots show the distribution of treatment-related mortality (TRM, blue) and disease-related mortality (red) among patients treated with VenAza or ICH across 3 follow-up intervals.

Consolidation and long-term outcomes

Median follow-up was shorter in VenAza (14.4 months) than ICH (45.9 months). Second-line therapy was required in 22% of patients, and cytarabine consolidation was more frequent with ICH (39.3% vs 9.1%; P = .002). HSCT was performed in 31% overall, with comparable rates and timing across groups (Table 3).

Postinduction therapy, transplantation, and long-term outcomes by treatment group

| . | Total (N = 100) . | VenAza (n = 44) . | ICH (n = 56) . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subsequent therapy, n (%) | .002 | |||

| Second line | 22 (22) | 12 (27.3) | 10 (17.9) | |

| Cytarabine∗ | 26 (26) | 4 (9.1) | 22 (39.3) | |

| Venetoclax + Azacitidine | 8 (8) | 5 (11.4) | 3 (5.4) | |

| Consolidative HSCT | 8 (8) | 6 (13.6) | 2 (3.6) | |

| None | 32 (32) | 13 (29.5) | 19 (33.9) | |

| Palliative care | 4 (4) | 4 (9.1) | 0 (0) | |

| HSCT, n (%) | 31 (31) | 14 (31.8) | 17 (30.4) | .88 |

| Time to HSCT, median (range), d | 140 (43-421) | 112 (43-255) | 154 (57-421) | .34 |

| Long-term outcomes | ||||

| Relapse (n = 47), n (%) | 30 (63.8) | 6 (35.3) | 24 (80) | .002 |

| Time to relapse (n = 30), median (range), mo | 5.8 (1.6-53.1) | 5.9 (1.8-13.1) | 5.8 (1.6-53.1) | .68 |

| Event, n (%) | 82 (82) | 31 (70.5) | 51 (91.1) | .008 |

| Time to event (months) | 2.4 (0-54.4) | 2.5 (0-16.3) | 0 (0-54.4) | .92 |

| Death, n (%) | 67 (67) | 22 (50) | 45 (80.4) | .001 |

| Cause of death, n (%) | .55 | |||

| Treatment related | 27 (40.3) | 10 (45.5) | 17 (37.8) | |

| Disease related | 40 (59.7) | 12 (54.5) | 28 (62.2) |

| . | Total (N = 100) . | VenAza (n = 44) . | ICH (n = 56) . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subsequent therapy, n (%) | .002 | |||

| Second line | 22 (22) | 12 (27.3) | 10 (17.9) | |

| Cytarabine∗ | 26 (26) | 4 (9.1) | 22 (39.3) | |

| Venetoclax + Azacitidine | 8 (8) | 5 (11.4) | 3 (5.4) | |

| Consolidative HSCT | 8 (8) | 6 (13.6) | 2 (3.6) | |

| None | 32 (32) | 13 (29.5) | 19 (33.9) | |

| Palliative care | 4 (4) | 4 (9.1) | 0 (0) | |

| HSCT, n (%) | 31 (31) | 14 (31.8) | 17 (30.4) | .88 |

| Time to HSCT, median (range), d | 140 (43-421) | 112 (43-255) | 154 (57-421) | .34 |

| Long-term outcomes | ||||

| Relapse (n = 47), n (%) | 30 (63.8) | 6 (35.3) | 24 (80) | .002 |

| Time to relapse (n = 30), median (range), mo | 5.8 (1.6-53.1) | 5.9 (1.8-13.1) | 5.8 (1.6-53.1) | .68 |

| Event, n (%) | 82 (82) | 31 (70.5) | 51 (91.1) | .008 |

| Time to event (months) | 2.4 (0-54.4) | 2.5 (0-16.3) | 0 (0-54.4) | .92 |

| Death, n (%) | 67 (67) | 22 (50) | 45 (80.4) | .001 |

| Cause of death, n (%) | .55 | |||

| Treatment related | 27 (40.3) | 10 (45.5) | 17 (37.8) | |

| Disease related | 40 (59.7) | 12 (54.5) | 28 (62.2) |

Bonferroni-adjusted post hoc analysis showed significant differences in this subgroup.

Relapse occurred in 63.8% of patients at a median of 5.8 months, and death in 67%, mainly disease related. At last follow-up, VenAza showed lower relapse (35.3% vs 80%; P = .002) and mortality (50% vs 80.4%; P = .001) (Table 3).

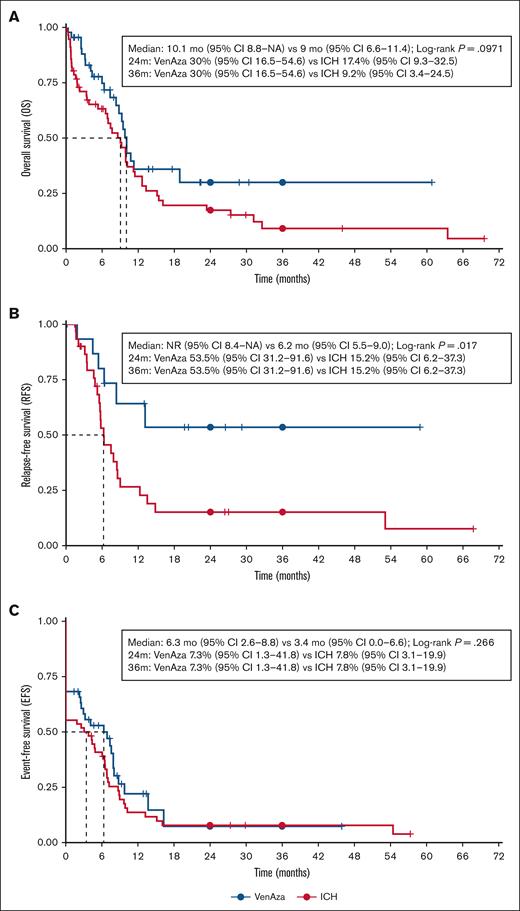

Median OS was 9.5 months overall, similar by group (10.1 months VenAza vs 9.0 months ICH; P = .097). RFS was longer with VenAza (NR vs 6.2 months; P = .017), whereas EFS was short in both (6.3 vs 3.4 months; P = .266) (Figure 2). In landmark analyses censoring HSCT, VenAza showed similar OS and EFS while significantly higher RFS (supplemental Figure 1). Multivariable Cox confirmed VenAza as independently associated with improved OS (HR, 1.82; P = .039) and RFS (HR, 3.23; P = .043), with a trend for EFS (HR, 1.72; P = .061) (Table 4).

Survival analysis in patients treated with low-dose VenAza or intensive chemotherapy. (A) The VenAza group showed comparable OS to ICH (median OS, 10.1 vs 9.0 months; P = .097), (B) and significantly longer relapse-free survival (not reached vs 6.2 months; P = .017). (C) No significant difference was observed in event-free survival (6.3 vs 3.4 months; P = .266). Survival analysis was performed in R using the survival and survminer packages. No image editing was applied beyond global formatting via ggplot2.

Survival analysis in patients treated with low-dose VenAza or intensive chemotherapy. (A) The VenAza group showed comparable OS to ICH (median OS, 10.1 vs 9.0 months; P = .097), (B) and significantly longer relapse-free survival (not reached vs 6.2 months; P = .017). (C) No significant difference was observed in event-free survival (6.3 vs 3.4 months; P = .266). Survival analysis was performed in R using the survival and survminer packages. No image editing was applied beyond global formatting via ggplot2.

Multivariable Cox regression analysis for OS, RFS, and EFS

| . | OS HR (95% CI) . | P value . | RFS HR (95% CI) . | P value . | EFS HR (95% CI) . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment group (ICH vs VenAza) | 1.82 (1.03-3.20) | .039 | 3.23 (1.04-10.08) | .043 | 1.72 (0.98-3.04) | .061 |

| Age (per year) | 1.02 (1.00-1.03) | .061 | 1.00 (0.97-1.02) | .761 | 1.01 (0.99-1.03) | .206 |

| Secondary AML (vs de novo) | 0.80 (0.36-1.78) | .584 | 1.48 (0.26-8.53) | .664 | 1.39 (0.70-2.78) | .347 |

| Risk (adverse vs nonadverse) | 1.39 (0.70-2.77) | .345 | 1.43 (0.54-3.79) | .474 | 1.19 (0.64-2.23) | .585 |

| Risk (unknown vs nonadverse) | 1.53 (0.87-2.71) | .143 | 1.27 (0.49-3.34) | .622 | 1.77 (1.07-2.91) | .025 |

| . | OS HR (95% CI) . | P value . | RFS HR (95% CI) . | P value . | EFS HR (95% CI) . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment group (ICH vs VenAza) | 1.82 (1.03-3.20) | .039 | 3.23 (1.04-10.08) | .043 | 1.72 (0.98-3.04) | .061 |

| Age (per year) | 1.02 (1.00-1.03) | .061 | 1.00 (0.97-1.02) | .761 | 1.01 (0.99-1.03) | .206 |

| Secondary AML (vs de novo) | 0.80 (0.36-1.78) | .584 | 1.48 (0.26-8.53) | .664 | 1.39 (0.70-2.78) | .347 |

| Risk (adverse vs nonadverse) | 1.39 (0.70-2.77) | .345 | 1.43 (0.54-3.79) | .474 | 1.19 (0.64-2.23) | .585 |

| Risk (unknown vs nonadverse) | 1.53 (0.87-2.71) | .143 | 1.27 (0.49-3.34) | .622 | 1.77 (1.07-2.91) | .025 |

The treatment group remained independently associated with OS and RFS, while unknown-risk patients showed inferior EFS. Other baseline covariates were not significant. Bold values reflect P <.05.

In subgroup analyses, OS/EFS were similar across cytogenetic risk groups, though RFS was longest in VenAza nonadverse (supplemental Figure 2). By HSCT status, VenAza + HSCT achieved the most favorable OS/RFS, whereas VenAza without HSCT showed RFS comparable to ICH+HSCT (supplemental Figure 3).

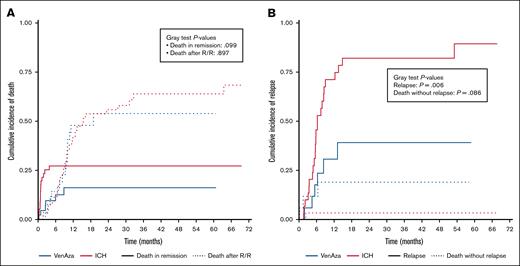

Regarding death after relapse/refractory disease, cumulative incidence was similar between groups: at 12 months, 41.1% (ICH) vs 47.9% (VenAza), at 24 months 55.9% vs 53.9%, and at last follow-up 68.3% vs 53.9% (P = .89) (Figure 3A). Death without relapse remained rare: 3.3% in VenAza vs 11.8% in ICH at 2 years, and by last follow-up unchanged in VenAza (3.3%) but rising to 18.9% in ICH (P = .09) (Figure 3A). Relapse was consistently lower with VenAza: 1-year incidence 5.8% vs 71.1% (ICH), 2-year 30.7% vs 82.1%, and at last follow-up 39.1% vs 89.4% (P = .006) (Figure 3B).

Cumulative incidence of relapse and death in patients treated with low-dose VenAza or ICH. (A) Death in remission occurred in 16.2% (VenAza) vs 27.2% (ICH) (P = .09). Death after relapse was comparable between groups. (B) At last follow-up, cumulative incidence of relapse was lower in the VenAza group (39.1%) than in ICH (89.4%; P = .006). Competing risks were analyzed using the Fine-Gray model implemented in the cmprsk package in R. Plots were generated with ggplot2, and no manual image processing was applied.

Cumulative incidence of relapse and death in patients treated with low-dose VenAza or ICH. (A) Death in remission occurred in 16.2% (VenAza) vs 27.2% (ICH) (P = .09). Death after relapse was comparable between groups. (B) At last follow-up, cumulative incidence of relapse was lower in the VenAza group (39.1%) than in ICH (89.4%; P = .006). Competing risks were analyzed using the Fine-Gray model implemented in the cmprsk package in R. Plots were generated with ggplot2, and no manual image processing was applied.

Discussion

In this retrospective comparative study, we assessed the efficacy and safety of low-dose VenAza vs conventional cytarabine-anthracycline induction in newly diagnosed patients with AML eligible for intensive therapy. Despite the VenAza cohort having a higher-risk profile, including older age, more secondary AML, and a greater prevalence of adverse-risk ELN 2017, this regimen showed clear safety advantages: lower early mortality, fewer complications, shorter hospitalizations, and reduced incidence of neutropenic fever (Table 2).

Efficacy was comparable in terms of CR/CRi, with lower relapse rates, fewer events, and improved RFS (Table 2; Figure 2). A similar OS and reduced cumulative incidence of death in remission was observed with VenAza (Figures 2 and 3). These findings suggest that VenAza may represent a safer and similarly effective alternative to ICH, particularly in resource-limited settings where early mortality remains a major barrier.

VenAza was associated with significantly lower hospitalization rates (50% vs 98.2%; P = .0001) and shorter hospital stays (median, 14 vs 28 days) compared with ICH (Table 2). These findings align with previous studies reporting longer hospital stays with the 7+3 regimen (15.5 days vs 31.5 days) and outpatient management in up to 20% of Ven/hypomethylating agent (HMA) patients.12 Notably, half of the patients in the VenAza group completed induction entirely on an outpatient basis, compared with only 1.8% in the ICH group (P < .0001) (Table 2). This highlights VenAza's potential to reduce hospitalization burden, which is particularly relevant in settings with limited inpatient capacity.

VenAza also resulted in fewer complications (54.5% vs 98.1%; P = .0001), mainly because of a significant reduction in neutropenic fever (50% vs 90.6%; P = .0001) (Table 2). These findings are consistent with previous data showing higher febrile neutropenia rates (47% vs 93%; P < .001) and culture-positive infections (21% vs 44%; P = .004) with 7+3 compared with VenAza.12 Additional trials report febrile neutropenia in 55% of patients receiving 7+3 plus venetoclax, with pneumonia in 21% and sepsis in 12%,13 whereas another multicenter study found febrile neutropenia in 90.5% of patients receiving venetoclax with DA 2+6.14

Importantly, real-world studies support these findings. Shen et al reported lower rates of neutropenia (79% vs 91.2%; P = .05), anemia (58.1% vs 82.4%; P = .002), and infections (38.7% vs 58.8%; P = .022) in the VenAza group.15 In addition, Brandwein et al noted an initial early mortality rate of 22% with VenAza, which improved to 8% with increasing clinician experience, underscoring the importance of proper patient selection and infection prophylaxis.16 Our study confirmed these findings, demonstrating a significantly lower 60-day mortality rate in the VenAza group (4.5% vs 26.8%; P = .003) (Figure 1), which is consistent with prior reports on ICH 60-day mortality ranging from 16% to 29%.7,17,18 Additionally, a retrospective analysis of 56 patients with AML treated with venetoclax-based regimens reported a 30-day early mortality rate of only 3.5%,19 whereas a United States-based study found overall 60-day mortality rates of 10.1%.20 Notably, 1 retrospective study observed higher early mortality with venetoclax/HMA compared with 7+3 (15% vs 6%),12 although this discrepancy may be influenced by differences in baseline patient characteristics and institutional treatment protocols. These findings reinforce the potential of VenAza as a safer alternative.20

Efficacy comparisons between ICH, full-dose VenAza, and low-dose VenAza plus itraconazole suggest relative similarity in response rates. Historically, ICH in our population yields CR rates ranging from 62% to 71.3%.13,14,21 Large retrospective studies evaluating lower-dose Ven/HMA (ie, 100-400 mg for 14, 21, or 28 days) report composite CR/CRi rates ranging from 58% to 78.6% vs 45.9% in patients assessed in our data set.20,22 A propensity score-matched analysis of 276 adult ND-AML patients comparing VenAza vs ICH found that CR rates were significantly higher in the ICH group (60.9% vs 44.2%).23 Recent studies further support these findings. Shen et al (15), in a cohort of 142 patients with core-binding factor ND-AML, compared ICH (idarubicin [IDA] 10-12 mg/m2 for 3 days and Ara-C 100 mg/m2 for 7 days) vs venetoclax-based regimens (VenAza or VenCytarabine, 400 mg per cycle of 28 days). Their results showed comparable CR rates (94.9% vs 88.9%; P = .184), suggesting that venetoclax-based regimens can achieve similar deep remissions in favorable-risk subgroups. Likewise, a real-world study by Brandwein et al found an ORR of 66% with VenAza, further supporting its efficacy as an alternative induction strategy.16 Zhong et al examined the impact of adding azole antifungals (excluding itraconazole) to VenAza in unfit patients with ND-AML, reporting ORR rates of 96.2% vs 80.0% (P = .073) and CR rates of 50% vs 56% (P = .096), with no significant differences between groups.24

The addition of venetoclax to ICH has been associated with higher toxicity but also deeper MRD-negative remissions, which may facilitate transition to allo-HSCT in first remission (79% vs 57%; HR, 1.52; P = .012).25 Similarly, trials using venetoclax in combination with daunorubicin and cytarabine (DAV regimen) have reported high CR/CRi rates of 91%, with 97% achieving undetectable MRD.13 Another study assessing venetoclax with DA 2+6 in patients with ND-AML found an ORR of 92.9% and an MRD-negative CR rate of 87.9%.14

Although ICH remains the standard of care for fit patients, including venetoclax in a less toxic induction regimen could balance the benefit/risk ratio. However, the choice between VenAza, ICH, or ICH plus venetoclax remains an open question, particularly in the context of individual patient risk factors and resource availability.

In our previous phase 2 study,6 we reported median OS of 7.4 months (95% CI, 1.3-13.5) and RFS of 9 months (95% CI, 9-NA), findings consistent with similar resource-limited settings and outcomes in older adults receiving ICH in high-income countries.26 In our analysis, OS was similar between VenAza and ICH, whereas RFS was significantly longer with VenAza (Figure 2). However, the impact of access to consolidation therapies and allogeneic transplantation must be considered in survival outcomes, as previous studies in Latin America suggest that limited access to HSCT significantly influences long-term prognosis.21

A real-world study by Brandwein et al evaluating VenAza in first-line therapy for unfit patients with ND-AML reported a median OS of 9.6 months (95% CI, 6.7-12.5) and a reduction in early mortality from 22% to 8% as the learning curve improved.16 Similarly, a retrospective study found that modified venetoclax schedules were associated with longer OS (P = .02), reinforcing the role of individualized dose adjustments in optimizing patient outcomes.20

A large retrospective study analyzing first-line VenAza therapy reported median OS of 13.3 months, dropping to 5 months for second-line therapy and 4 months for post-alloHSCT relapse.19 Another real-world study comparing 7+3 with VenAza showed a median OS of 22 months vs 10 months, respectively, with an adjusted analysis favoring 7+3 (HR, 0.71; P = .026).12 However, in a single-center cohort study of 136 t-AML or patients with AML with myelodysplasia-related changes (MRC), OS was similar between 7+3 and HMA (11.2 vs 10.6 months; P > .05), whereas Ven + HMA had worse OS compared with 7+3 (5.3 vs 20.2 months; P = .02).27

Regarding survival benefits with venetoclax, a phase 2 trial of 7+3 plus venetoclax reported a 1-year OS of 97% (95% CI, 91-100) and 1-year EFS of 72% (56-94).12 Similarly, the DA 2+6 regimen achieved a 12-month OS of 83.1% (95% CI, 78.8-87.4).14 In addition, integrating venetoclax into ICH regimens has demonstrated improved EFS (median, not reached vs 14.3 months; HR, 0.57; P = .030).25

A recent study by Shen et al comparing VenAza with ICH in 142 patients with core-binding factor ND-AML found no significant difference in OS (P = .184) but a lower incidence of neutropenia (79% vs 91.2%; P = .05), anemia (58.1% vs 82.4%; P = .002), and infections (38.7% vs 58.8%; P = .022) in the VenAza group.15 Meanwhile, Zhong et al evaluated VenAza plus azoles vs VenAza alone in unfit patients with ND-AML, reporting no significant differences in ORR (96.2% vs 80.0%; P = .073) or CR (50% vs 56%; P = .096), but a significantly lower cost of therapy in the azole group (14 153.85 renminbi [RMB] vs 31 269.57 RMB; P = .038).24

Finally, a retrospective analysis comparing intensive chemotherapy with full-dose VenAza found no significant difference in median OS (13.7 vs 10.6 months; P > .05).23 Similarly, RFS values without censoring (12.0 vs 9.5 months) and with censoring at HSCT (6.4 vs 7.4 months) were not significantly different (P > .05 for both).23 In high-risk AML subtypes (t-AML and AML-MRC), EFS and relative mortality rates were comparable across 7+3, HMA, Ven+HMA, and CPX-351 (P > .05).27

This retrospective study has inherent limitations, such as potential selection and information biases, incomplete data collection, and lack of MRD and molecular status. These factors limit causal inference, and prospective controlled trials are needed to validate our findings. Conducted in 2 Mexican centers under resource-limited conditions, results may not generalize to higher-resource systems.

Cytarabine-based chemotherapy heterogeneity (5-7 days) may have affected comparability of responses and toxicity. Some patients lacked marrow reassessment due to early death or instability, likely biasing ORR estimates. MRD by flow cytometry was only available to those able to pay, whereas molecular MRD was unavailable, limiting uniform depth-of-response evaluation. The effect of HSCT cannot be fully disentangled from induction therapy, and unequal access may have influenced long-term outcomes. Shorter follow-up in the VenAza cohort (median, 14.4 months) limits assessment of late relapses.

Baseline age and cytogenetic differences reflected shifts in practice during COVID-19, when VenAza became the default frontline option, broadening eligibility beyond the earlier ICH cohort. This introduces a nonconcurrent design effect, potentially biasing outcomes against VenAza. In addition, time-related improvements in supportive care and infection management could have contributed to differences in morbidity and mortality across periods; however, barriers such as limited access to multiplex polymerase chain reaction testing and novel antifungals remain in our setting.

The mortality reduction with VenAza likely stems from fewer complications, lower hospitalization, and shorter stays, making it especially advantageous in low-resource settings. Although concerns exist about intentional CYP inhibition with itraconazole, in our setting it was essential for venetoclax feasibility. Emerging evidence indicates itraconazole does not compromise AML survival and is already integrated into clinical practice by other groups, further supporting feasibility.24,28

Ongoing prospective trials (eg, NCT04801797) will clarify the role of VenAza vs intensive chemotherapy. If validated, this regimen could represent a safer, cost-effective alternative in resource-limited environments.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our retrospective study pioneers a comparison between low-dose venetoclax and itraconazole vs conventional ICH for ND-AML. Despite the retrospective design and heterogeneous patient population, our findings reveal a promising alternative in the venetoclax-itraconazole regimen. Remarkably, despite older age and higher leukemia risk in the venetoclax group, this approach demonstrated reduced hospitalizations, shorter stays, and lower relapses, while achieving a 75% dose reduction in venetoclax compared with standard VenAza. These results suggest a favorable cost-benefit-risk profile, warranting further investigation to potentially reshape leukemia treatment paradigms.

Authorship

Contribution: F.D.l.G.-S. performed conceptualization, investigation, data curation, formal analysis, visualization, and methodology, and wrote the original draft and reviewed and edited it; Y.K.L.-G., A.D.l.R.-F., P.U.-P., and J.C.O.-G. performed data collection and investigation; G.R.-A. assisted with validation, and wrote, reviewed, and edited the manuscript; D.G.-A. performed conceptualization and supervision, accumulated resources, and wrote, reviewed, and edited the manuscript; and A.G.-D.L. performed conceptualization, supervision, investigation, and project administration, and wrote, reviewed, and edited the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: D.G.-A. reports consulting or advisory role with Janssen, Takeda, Teva, and BMS; and speakers' bureau role for AbbVie, Novartis, Janssen, Amgen, Takeda, Roche, Sanofi, Teva, Astra Pharma, BMS, and Asofarma. A.G.-D.L. received honoraria from Novartis, AbbVie, Sanfer, Amgen, Janssen, and Sanofi; and reports consulting or advisory role with AstraZeneca, Sanofi/Aventis, Pfizer, and Merck Sharp & Dohme. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Andrés Gómez-De León, Centro Universitario Contra el Cáncer, Francisco I. Madero and Gonzalitos Ave, Mitras Centro, 64460 Monterrey, México; email: andres.gomezd@uanl.edu.mx.

References

Author notes

Data are available from the corresponding author, Andrés Gómez-De León (andres.gomezd@uanl.edu.mx).

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.