Key Points

Tailored infectious screening, including endemic pathogens, is critical in CAR-T candidates in endemic areas.

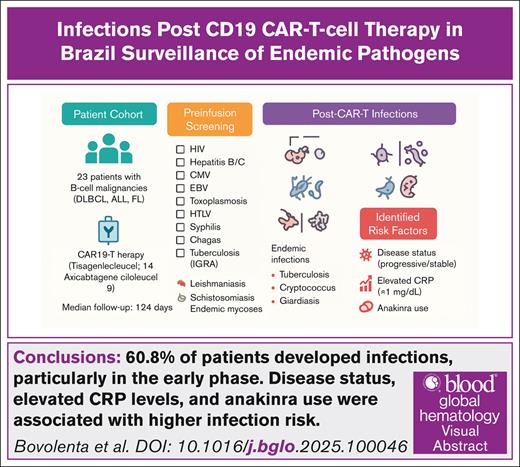

Visual Abstract

Infectious complications remain a major concern after chimeric antigen receptor T-cell (CAR-T) therapy, particularly in low- and middle-income countries where endemic pathogens may increase risk. We retrospectively studied 23 patients with relapsed/refractory B-cell malignancies (18 diagnosed with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, 3 with acute lymphoblastic leukemia, and 2 with follicular lymphoma) treated with CD19-directed CAR-T therapy (tisagenlecleucel or axicabtagene ciloleucel) at a single Brazilian center between February 2023 and January 2025. During a median follow-up of 124 days, 33 infectious episodes occurred, including 18 early (≤30 days) and 15 late events (>30 days). Consistent with existing literature, the highest incidence was within the first month after infusion, with bacterial infections, Candida tropicalis and Candida krusei, and cytomegalovirus (CMV) reactivation predominating, whereas respiratory viral infections were more frequent thereafter. Three patients developed endemic infections (tuberculosis, cryptococcosis, and giardiasis). CMV reactivation and probable aspergillosis were observed in 13% of patients each. Overall, 10 patients died, including 2 from infection and 8 from disease progression. A complementary literature review regarding endemic infections after CAR-T therapy was performed, highlighting tuberculosis, endemic fungal, and protozoan infections as important considerations for post–CAR-T management in endemic areas. Our findings emphasize the importance of early surveillance for infectious complications after CAR-T therapy, including attention to endemic pathogens in Latin America.

Introduction

Chimeric antigen receptor T-cell (CAR-T) therapy has emerged as a transformative treatment for relapsed or refractory B-cell malignancies, including diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), follicular lymphoma (FL), and acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL).1

Infectious complications are among the most frequent adverse events after CAR-T therapy, driven by therapy-induced cytopenia, immune dysregulation, and immunosuppressive treatments.2-9 Current literature primarily describes infection patterns according to timing after infusion, with the highest incidence within the first month.6-12 Early infections are mainly bacterial and cytomegalovirus (CMV) reactivation, whereas respiratory viral infections predominate later.7,9,11,13-24

In low- and middle-income countries, endemic pathogens, including Mycobacterium tuberculosis, protozoa, and regionally prevalent fungi, pose additional risks that may not be captured in cohorts from high-income settings.25-31 Limited data exist regarding the incidence and characteristics of these infections after CAR-T therapy.

We aim to retrospectively describe infectious complications after CAR-T therapy in a Brazilian cohort and provide a contemporary literature review regarding endemic pathogens.

Methods

This is a retrospective cohort of patients aged 18 years diagnosed with refractory/relapsed B-cell malignancies (DLBCL, ALL, and FL) treated with CAR 19 T-cell (tisagenlecleucel and axicabtagene ciloleucel) therapy at the A.C. Camargo Cancer Center between February 2023 and January 2025. Medical records were reviewed, and patient demographics, laboratory data, and clinical treatment data were collected. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 30.0.0 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY). Categorical variables were compared using χ2 or Fisher exact tests, as appropriate. Univariate analyses were conducted to evaluate potential predictors of infection, with results expressed as odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs); P values <.05 were considered statistically significant. For multivariable model construction, variables with a P value ≤.20 in univariate analyses were considered for inclusion, based on the likelihood ratio test to identify independent predictors of infection.

A literature review was also performed to identify cases of endemic infections in patients who received CAR-T therapy targeting CD19 cells. The search was performed in PubMed, Embase, LILACS, and Cochrane databases, covering the period from 2015 to 2025. We used MeSH (Medical Subject Headings) terms for “CAR-T therapy,” “endemic infections,” and “CD19,” in combination with specific terms for endemic diseases such as tuberculosis, endemic fungal infections, protozoal infections, toxoplasmosis, dengue, Zika, chikungunya, leishmaniasis, yellow fever, malaria, leprosy, Chagas disease, and schistosomiasis. Data on CAR-T patients, included age, sex, infection diagnosis, hematologic diagnosis, the infection diagnostic method used, type of CAR-T therapy, conditioning regimen, cytokine release syndrome (CRS) degree, CRS treatment, cellular immune reconstitution, infection treatment, and outcome, were extracted. We found 687 articles and selected 8 of them that contained reports of endemic infections in the context of CAR-T therapy. Only articles published in English were included.

Ethical implications

The A.C. Camargo Cancer Center Institutional Review Board approved this retrospective study (number 3335/22). Informed consent was obtained from all patients before being included in the study. All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1964, as revised in 2008.

Results

We retrospectively analyzed 23 consecutive patients with hematologic malignancies who underwent CAR-T therapy during a median follow-up of 124 days. Among them, 18 were diagnosed with DLBCL, 2 with FL, and 3 with ALL.

All patients underwent institutional protocols for preinfusion infectious disease screening, infectious prophylaxis, and lymphodepletion chemotherapy, which are detailed below.

Epidemiological and serological infectious disease prescreening

All patients underwent serological tests for HIV (enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay), hepatitis B, hepatitis C, toxoplasmosis, CMV, Epstein-Barr virus, human T-lymphotropic virus, syphilis, Chagas disease, and tuberculosis (interferon gamma release assays) before the start of lymphodepletion. Based on epidemiological exposure and for patients who come from endemic areas, additional serologies such as leishmaniasis, schistosomiasis, and endemic mycosis were also performed.

We had 2 patients with positive QuantiFERON test, and no other patient had a positive preinfusion screening for other endemic diseases.

Institution guidelines for infectious prophylaxis

All patients had received standard infectious prophylaxis consisting of acyclovir 400 mg every 12 hours and anti–Pneumocystis jirovecii prophylaxis with sulfamethoxazole and trimethoprim 800/160 mg 3 times a week for a minimum of 1 year and 6 months or until CD4+ lymphocyte counts were >200 cells per mm3. Levofloxacin and fluconazole were given when absolute neutrophil count dropped to <500 cells per mm3 either until discharge or before if neutrophil count recovered, whichever occurred first. Patients with positive QuantiFERON test received isoniazid prophylaxis. We do not practice routine immunoglobulin replacement for all patients with immunoglobulin G <400 mg/dL and prefer to guide the decision individually.

Lymphodepletion chemotherapy

All patients received lymphodepleting chemotherapy consisting of cyclophosphamide 300 to 500 mg/m2 and fludarabine 30 mg/m2 for 3 consecutive days, followed by a single infusion of tisagenlecleucel (n = 14) or axicabtagene ciloleucel (n = 9) 2 days after the end of lymphodepletion.

The patient’s course through CAR-T therapy, highlighting the rationale for preinfusion infectious disease screening and the impact on immune function, is illustrated in Figure 1.

Infection disease screening and follow-up in CAR-T therapy recipients. Journey of a patient undergoing cell therapy with CAR-Ts, with emphasis on the need for preinfusion screening, considering endemic diseases, and previous exposure. After lymphodepletion (day –5 to day –3) and infusion (day 0), the patient goes through all the expected stages of therapy with damage to the immune system and greater susceptibility to infectious agents, requiring long-term follow-up. Anti–IL-6, anti–interleukin-6; D-5, day –5; ID, infectious disease. Figure created with BioRender.com.

Infection disease screening and follow-up in CAR-T therapy recipients. Journey of a patient undergoing cell therapy with CAR-Ts, with emphasis on the need for preinfusion screening, considering endemic diseases, and previous exposure. After lymphodepletion (day –5 to day –3) and infusion (day 0), the patient goes through all the expected stages of therapy with damage to the immune system and greater susceptibility to infectious agents, requiring long-term follow-up. Anti–IL-6, anti–interleukin-6; D-5, day –5; ID, infectious disease. Figure created with BioRender.com.

Table 1 presents the descriptive epidemiological and clinical characteristics of the patient cohort before CAR-T infusion. The median age was 54 years, and most patients were male (n = 15 [65.5%]). Most patients had advanced disease (89%), and among those with lymphoma (DLBCL and FL), 35.3% had a high tumor burden. Most patients received cellular therapy during disease progression or with stable disease (60%), and 17.4% had an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group score of ≥2. All had received at least 3 prior lines of therapy, with 43.5% having previously undergone autologous or allogeneic transplantation. All patients received lymphodepletion conditioning with fludarabine and cyclophosphamide scheme. Fourteen patients received an infusion of tisagenlecleucel, and 9 received axicabtagene ciloleucel. Table 1 provides an overview of the laboratory and immunological assessments conducted before lymphodepletion.

Univariate and multivariate analysis of risk factors for infection in patients treated with CAR19 T cells

| Characteristics/univariate analysis . | Total (N = 23), n (%) . | Infection (n = 14), n (%) . | No infection (n = 9), n (%) . | OR (95% CI) . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, median (range), y | 54 (18-77) | 47.5 (18-77) | 59 (24-74) | 0.9 (0.9-1.0) | .30 |

| Male sex | 15 (65.2) | 10 (71.4) | 5 (55.5) | 0.5 (0.08-2.8) | .43 |

| Hematologic diagnosis | |||||

| DLBCL | 18 (78.3) | 11 (78.5) | 7 (77.7) | — | — |

| ALL | 3 (13) | 2 (14.2) | 1 (11.1) | 0.7 (0.05-10.3) | .85 |

| FL | 2 (8.7) | 1 (7.1) | 1 (11.1) | 1.5 (0.08-29.4) | .76 |

| Advanced staging, Ann Arbor III or IV (DLBCL/FL), n (%) | 17/19 (89.5) | 11/12 (91.6) | 6/7 (85.7) | 1.8 (0.09-34.8) | .68 |

| Tumor burden >6 cm (DLBCL/FL) | 6/17 (35.3) | 4/11 (36.3) | 2/6 (33.3) | 1.1 (0.1-9.2) | .90 |

| Response before LD (DLBCL/FL) | |||||

| PD or ED vs CR or PR | 12/20 (60) | 10/12 (83.3) | 2/8 (25) | 15.0 (1.6-136.1) | .01 |

| ECOG ≥2 | 4 (17.4) | 3 (21.4) | 1 (11.1) | 2.1 (0.1-25.0) | .53 |

| Prior treatment, ≥3 lines | 23 (100) | - | - | - | - |

| Prior autologous or allogeneic BMT | 10 (43.5) | 7 (50) | 3 (33.3) | 2.0 (0.3-11.3) | .43 |

| CAR19 T cell | |||||

| Tisagenlecleucel | 14 (60.9) | 9 (64.2) | 5 (55.5) | - | - |

| Axicabtagene ciloleucel | 9 (39.1) | 5 (35.7) | 4 (44.4) | 0.6 (0.1-3.8) | .67 |

| LDH ≥250 U/L before LD | 13 (56.5) | 10 (71.4) | 3 (33.3) | 5.0 (0.8-30.4) | .08 |

| CRP ≥1 mg/dL before LD | 14/22 (63.6) | 11/13 (84.6) | 3/9 (33.3) | 11 (1.4-85.2) | .02 |

| Ferritin ≥500 ng/mL before LD | 16/18 (88.9) | 11/11 (100) | 5/7 (71.4) | - | - |

| Immunological evaluation before LD | |||||

| IgG <400 mg/dL | 8/17 (47.1) | 6/10 (60) | 2/7 (28.5) | 3.7 (0.4-29.7) | .21 |

| IgM <40 mg/dL | 15/17 (88.2) | 9/10 (90) | 6/7 (85.7) | 1.5 (0.07-28.8) | .78 |

| IgA <70 mg/dL | 12/17 (70.6) | 8/10 (80) | 4/7 (57.1) | 3.0 (0.3-25.8) | .31 |

| CD4 count <200 cells per mm3 | 14/14 (100) | - | - | - | - |

| CRS grade 3-4 | 4 (17.4) | 3 (21.4) | 1 (11.1) | 2.1 (0.1-25.0) | .53 |

| ICANS | 14 (60.9) | 9 (64.2) | 5 (55.5) | 1.4 (0.2-7.9) | .67 |

| Use of steroids | 16 (69.6) | 10 (71.4) | 6 (66.6) | 1.2 (0.2-7.6) | .80 |

| Use of tocilizumab | 19 (82.6) | 12 (85.7) | 7 (77.7) | 1.7 (0.1-15.0) | .62 |

| Use of anakinra | 8/22 (36.4) | 7/13 (53.8) | 1/9 (11.1) | 9.3 (0.8-97.6) | .06 |

| CAR-HEMATOTOX | |||||

| High risk, ≥2 | 17/21 (81) | 11/13 (84.6) | 6/8 (75) | 1.8 (0.2-16.5) | .58 |

| ICU admission | 12/22 (54.5) | 10/14 (71.4) | 2/8 (25) | 7.5 (1.0-54.1) | .04 |

| Multivariate analysis | |||||

| Use of anakinra | 48.1 (1.0-2191) | .04 | |||

| LDH ≥250 U/L before LD | 7.9 (0.3-161.0) | .17 | |||

| Response before LD (DLBCL/FL), PD or ED vs CR or PR | 15.4 (0.9-265.4) | .05 |

| Characteristics/univariate analysis . | Total (N = 23), n (%) . | Infection (n = 14), n (%) . | No infection (n = 9), n (%) . | OR (95% CI) . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, median (range), y | 54 (18-77) | 47.5 (18-77) | 59 (24-74) | 0.9 (0.9-1.0) | .30 |

| Male sex | 15 (65.2) | 10 (71.4) | 5 (55.5) | 0.5 (0.08-2.8) | .43 |

| Hematologic diagnosis | |||||

| DLBCL | 18 (78.3) | 11 (78.5) | 7 (77.7) | — | — |

| ALL | 3 (13) | 2 (14.2) | 1 (11.1) | 0.7 (0.05-10.3) | .85 |

| FL | 2 (8.7) | 1 (7.1) | 1 (11.1) | 1.5 (0.08-29.4) | .76 |

| Advanced staging, Ann Arbor III or IV (DLBCL/FL), n (%) | 17/19 (89.5) | 11/12 (91.6) | 6/7 (85.7) | 1.8 (0.09-34.8) | .68 |

| Tumor burden >6 cm (DLBCL/FL) | 6/17 (35.3) | 4/11 (36.3) | 2/6 (33.3) | 1.1 (0.1-9.2) | .90 |

| Response before LD (DLBCL/FL) | |||||

| PD or ED vs CR or PR | 12/20 (60) | 10/12 (83.3) | 2/8 (25) | 15.0 (1.6-136.1) | .01 |

| ECOG ≥2 | 4 (17.4) | 3 (21.4) | 1 (11.1) | 2.1 (0.1-25.0) | .53 |

| Prior treatment, ≥3 lines | 23 (100) | - | - | - | - |

| Prior autologous or allogeneic BMT | 10 (43.5) | 7 (50) | 3 (33.3) | 2.0 (0.3-11.3) | .43 |

| CAR19 T cell | |||||

| Tisagenlecleucel | 14 (60.9) | 9 (64.2) | 5 (55.5) | - | - |

| Axicabtagene ciloleucel | 9 (39.1) | 5 (35.7) | 4 (44.4) | 0.6 (0.1-3.8) | .67 |

| LDH ≥250 U/L before LD | 13 (56.5) | 10 (71.4) | 3 (33.3) | 5.0 (0.8-30.4) | .08 |

| CRP ≥1 mg/dL before LD | 14/22 (63.6) | 11/13 (84.6) | 3/9 (33.3) | 11 (1.4-85.2) | .02 |

| Ferritin ≥500 ng/mL before LD | 16/18 (88.9) | 11/11 (100) | 5/7 (71.4) | - | - |

| Immunological evaluation before LD | |||||

| IgG <400 mg/dL | 8/17 (47.1) | 6/10 (60) | 2/7 (28.5) | 3.7 (0.4-29.7) | .21 |

| IgM <40 mg/dL | 15/17 (88.2) | 9/10 (90) | 6/7 (85.7) | 1.5 (0.07-28.8) | .78 |

| IgA <70 mg/dL | 12/17 (70.6) | 8/10 (80) | 4/7 (57.1) | 3.0 (0.3-25.8) | .31 |

| CD4 count <200 cells per mm3 | 14/14 (100) | - | - | - | - |

| CRS grade 3-4 | 4 (17.4) | 3 (21.4) | 1 (11.1) | 2.1 (0.1-25.0) | .53 |

| ICANS | 14 (60.9) | 9 (64.2) | 5 (55.5) | 1.4 (0.2-7.9) | .67 |

| Use of steroids | 16 (69.6) | 10 (71.4) | 6 (66.6) | 1.2 (0.2-7.6) | .80 |

| Use of tocilizumab | 19 (82.6) | 12 (85.7) | 7 (77.7) | 1.7 (0.1-15.0) | .62 |

| Use of anakinra | 8/22 (36.4) | 7/13 (53.8) | 1/9 (11.1) | 9.3 (0.8-97.6) | .06 |

| CAR-HEMATOTOX | |||||

| High risk, ≥2 | 17/21 (81) | 11/13 (84.6) | 6/8 (75) | 1.8 (0.2-16.5) | .58 |

| ICU admission | 12/22 (54.5) | 10/14 (71.4) | 2/8 (25) | 7.5 (1.0-54.1) | .04 |

| Multivariate analysis | |||||

| Use of anakinra | 48.1 (1.0-2191) | .04 | |||

| LDH ≥250 U/L before LD | 7.9 (0.3-161.0) | .17 | |||

| Response before LD (DLBCL/FL), PD or ED vs CR or PR | 15.4 (0.9-265.4) | .05 |

BMT, bone marrow transplantation; CR, complete response; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; ED, estable disease; CAR-HEMATOTOX, CAR-T–related hematologic toxicity; IgG, immunoglobulin G; LD, lymphodepletion; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; PD, progressive disease; PR, partial response.

The bold values in Table 1 indicate statistical significance P < 0.05.

Four of 23 patients (17.4%) developed a grade 3 to 4 CRS. Fourteen (60.9%) developed any grade of immune effector cell–associated neurotoxicity syndrome (ICANS). Fourteen (69.6%) received corticosteroids after infusion, and 19 (82.6%) received tocilizumab. The median accumulated dose of dexamethasone was 40 mg. Nine patients received prophylactic corticosteroids.

In Table 1, the infection group had a higher incidence of patients with disease progression or stable disease at the time of infusion than those with complete or partial response (83% vs 25%; OR, 15.0; 95% CI, 1.6-136.1; P = .01). Additionally, CRP (C-reactive protein) levels >1 mg/dL were more frequent in this group (84% vs 33%; OR, 11.0; 95% CI, 1.4-85.2; P = .02), and intensive care unit (ICU) admissions were significantly higher (71% vs 25%; OR, 7.5; 95% CI, 1.0-54.1; P = .04).

Although not statistically significant, there was a trend toward higher lactate dehydrogenase levels (>250 U/L) in the infection group (71% vs 33%; OR, 5.0; 95% CI, 0.8-30.4; P = .08) and a greater tendency for anakinra use (53% vs 11%; OR, 9.3; 95% CI, 0.8-97.6; P = .06).

On univariate analysis, CRP levels >1 mg/dL were associated with an increased risk of early infection (90% vs 41%; OR, 12.6; 95% CI, 1.1-133.8; P = .03). The early infection group also had a significantly higher incidence of anakinra use (60% vs 16%; OR, 7.5; 95% CI, 1.0-54.1; P = .04) and ICU admissions (80% vs 33%; OR, 8.0; 95% CI, 1.1-56.7; P = .03).

In Table 1, we present the multivariate analysis regarding the presence of infection, considering anakinra use or nonuse, lactate dehydrogenase levels before lymphodepletion, and disease status. The results show that anakinra use and disease status remained statistically significant predictors of infection. Although corticosteroids and tocilizumab are recognized contributors to immunosuppression, their administration in our cohort was not associated with an increased risk of infection.

Table 2 describes the isolated pathogens in infectious disease episodes on early infections (up to 30 days after CAR-T infusion) and late infections (beyond 30 days after CAR-T infusion). All infections in our cohort were confirmed by microbiological evidence, including multiplex polymerase chain reaction (PCR) panels for respiratory, gastrointestinal, and meningitis pathogens, as well as plasma real-time PCR for CMV, adenovirus, polyomavirus, human herpesvirus 6, and Epstein-Barr virus. Aspergillosis was diagnosed using galactomannan testing, direct microscopy, and fungal cultures (MycoF medium, also applied for other fungi). Tuberculosis was diagnosed using GeneXpert Mycobacterium tuberculosis/rifampicin, direct acid-fast bacilli smear, and Löwenstein-Jensen culture.

Isolated pathogens in infectious disease episodes after lymphodepletion in 14 patients undergoing CAR19 T-cell therapy

| Documented infection, n (%) . | ≤30 d after CAR-T infusion (n = 18), n (%) . | >30 d after CAR-T infusion (n = 15), n (%) . |

|---|---|---|

| Bacterial | 9 (50) | 4 (26.6) |

| BSI | ||

| Escherichia coli | 1 (5.5) | 1 (6) |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | 1 (5.5) | |

| Staphylococcus epidermidis | 1 (5.5) | |

| Bacteroides fragilis | 1 (5.5) | |

| Staphylococcus aureus | 1 (5.5) | |

| Diarrhea | ||

| E coli, enteroaggregative | 1 (5.5) | |

| Clostridium difficile | 3 (16.6) | |

| Respiratory | ||

| Mycoplasma pneumoniae | 1 (6) | |

| S aureus | 1 (6) | |

| CNS, M tuberculosis∗ | 1† (6) | |

| Viral | 4 (22.2) | 9 (60) |

| Respiratory | ||

| Parainfluenza | 3 (20) | |

| Enterovirus | 1 (6) | |

| Rhinovirus | 1 (5.5) | 3 (20) |

| SARS-CoV-2 | 1 (6) | |

| BSI, CMV, CSCMVi | 3 (16.6) | |

| Diarrhea, norovirus | 1 (6) | |

| Fungi | 4 (22.2) | 2 (13.3) |

| BSI | ||

| Candida tropicalis | 1 (5.5) | |

| Candida krusei | 1‡ (5.5) a | |

| Respiratory, probable aspergillosis | 1 (5.5) | 2 (13.3) |

| Skin, Cryptococcus sp.∗ | 1 (5.5) | |

| Protozoan, Diarrhea, Giardia lamblia∗ | 1 (5.5) | |

| Total documented infection | 18 | 15 |

| Fever, febrile neutropenia without isolated germ/CRS | 6/23 (26) |

| Documented infection, n (%) . | ≤30 d after CAR-T infusion (n = 18), n (%) . | >30 d after CAR-T infusion (n = 15), n (%) . |

|---|---|---|

| Bacterial | 9 (50) | 4 (26.6) |

| BSI | ||

| Escherichia coli | 1 (5.5) | 1 (6) |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | 1 (5.5) | |

| Staphylococcus epidermidis | 1 (5.5) | |

| Bacteroides fragilis | 1 (5.5) | |

| Staphylococcus aureus | 1 (5.5) | |

| Diarrhea | ||

| E coli, enteroaggregative | 1 (5.5) | |

| Clostridium difficile | 3 (16.6) | |

| Respiratory | ||

| Mycoplasma pneumoniae | 1 (6) | |

| S aureus | 1 (6) | |

| CNS, M tuberculosis∗ | 1† (6) | |

| Viral | 4 (22.2) | 9 (60) |

| Respiratory | ||

| Parainfluenza | 3 (20) | |

| Enterovirus | 1 (6) | |

| Rhinovirus | 1 (5.5) | 3 (20) |

| SARS-CoV-2 | 1 (6) | |

| BSI, CMV, CSCMVi | 3 (16.6) | |

| Diarrhea, norovirus | 1 (6) | |

| Fungi | 4 (22.2) | 2 (13.3) |

| BSI | ||

| Candida tropicalis | 1 (5.5) | |

| Candida krusei | 1‡ (5.5) a | |

| Respiratory, probable aspergillosis | 1 (5.5) | 2 (13.3) |

| Skin, Cryptococcus sp.∗ | 1 (5.5) | |

| Protozoan, Diarrhea, Giardia lamblia∗ | 1 (5.5) | |

| Total documented infection | 18 | 15 |

| Fever, febrile neutropenia without isolated germ/CRS | 6/23 (26) |

CSCMVi represents CMV disease or CMV viremia leading to preemptive treatment.

BSI, bloodstream infection; CSCMVi, clinically significant CMV infection.

Endemic pathogens.

This patient had concomitant tuberculosis pulmonary and CNS infection.

This patient showed positive blood culture and urine culture for C krusei.

Six patients (26%) developed febrile neutropenia during hospitalization and after CAR-T infusion with no microbiological documentation. They received broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy and management according to institutional CRS protocol. There were 33 documented infections in 14 of 23 patients (60.8%), with an infection density of 1.43 infections for every 100 days at risk. Eighteen infections (9 bacterial, 4 viral, 4 fungal, and 1 protozoan) occurred in 10 patients within the first 30 days of CAR-T infusion, and 15 infections (4 bacterial, 9 viral, and 2 fungal) occurred in 9 patients after the first 30 days that followed infusion. In early infections, we observed the following by system: bloodstream infection (10/19), diarrhea (5/19), pulmonary (3/19), and skin (1/19). In late infections, we observed the following by system: bloodstream infection (1/19), diarrhea (1/19), pulmonary (13/19), and central nervous system (CNS; 1/19).

Three patients faced CMV reactivation in the bloodstream 30 days before CAR-T infusion; both received corticosteroids and at least 1 dose of tocilizumab. Two of them developed grade 2 CRS and the other grade 3 CRS. Six patients were diagnosed with invasive fungal infections, with 2 presenting Candida tropicalis and Candida krusei in the bloodstream. Three presented probable aspergillosis: 1 early infection and 2 late infections. One patient was diagnosed with Cryptococcus sp. on skin biopsy within 30 after CAR-T. One patient presented with a late infection of disseminated tuberculosis, confirmed in the cerebrospinal fluid by GeneXpert MTB/Rif, as well as pulmonary disease. Among patients treated with tisagenlecleucel, 50% developed early infections and 35% late infections, whereas among those receiving axicabtagene ciloleucel, 22% developed early infections and 44% late infections. Three patients developed endemic infections (tuberculosis, cryptococcosis, and giardiasis). Overall, 10 patients died, corresponding to an overall mortality rate of 43%, with an infection-related mortality of 8% (2 patients).

Considering there are few reports of endemic infections in the literature and the lack of standard screening, we performed a literature review in an academic medical setting and searched for cases of endemic infections after CAR-T infusion reported between 2015 and 2025.7,25-31 A total of 12 cases were identified, including tuberculosis, endemic fungi, and protozoa. A summary of these cases, along with detailed descriptions from our own cohort, is presented in Table 3.7,25-31

Literature review of endemic infections on CAR-T-cell recipients

| Sex/age Local . | Type and time∗ of infectious diagnosis . | Diagnosis method . | Hematologic diagnosis . | Type of CAR-T . | Conditioning regimen . | CRS grade . | CRS/ICANS treatment† . | Time to cellular immune recovery, neutrophil/B cells . | Infectious treatment . | Outcomes . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F/9 Born in Pakistan living in Spain for the past 3 y | Tuberculosis (pulmonary) on day +64 | PCR of BAL | ALL | CAR19-T-Cell | FC | 3 | Dexametasone 0.6 mg/kg per day for 13 days; tocilizumab 8 mg/kg per dose for 2 doses; siltuximab 11 mg/kg for 1 dose; anakinra 2 mg/kg per day for 3 d | 5 mo/5 mo | HRZE | Relapse of ALL and died at day +94 |

| M/45 China | Tuberculosis (pulmonary) on day +23 | Xpert MTB/Rif (sputum) | MCL | CAR19 T cell/CAR22 T cell + tandem ASCT | BEAM | 2 | Dexametasone 10 mg for 3 d | 14 d/3 mo | 2HRZE/4HR | Alive |

| F/29 China | Tuberculosis (pulmonary and CNS) on day +66 | Xpert MTB/Rif (CSF) | ALL | CAR19 T cell/CAR22 T cell | FC | 1 | Suportive | 7 d/3 mo | 2HRZE | Relapse of ALL 4 months after CAR-T and lost to FU |

| M/60 China | Tuberculosis (pulmonary and CNS) on +8 mo | Xpert MTB/Rif (PE); TB PCR (CSF) | DLBCL | CAR19 T cell/ CAR22 T cell + tandem ASCT | BEAM | 1 | Suportive | 20 d/10 mo | 2HRZE | Death due to CNS tuberculosis |

| M/23 China | Tuberculosis (pulmonary and nodal) on +10 mo | PCR (mediastinal lymph node biopsy) | DLBCL | CAR19 T cell/CAR22 T cell + tandem ASCT | BEAM | 1 | Suportive | 9 d/13 mo | 3HRZE/9HER | Alive |

| F/63 China | Tuberculosis (subcutaneous and bone) on +11 mo | PCR (subcutaneous nodules biopsy) | FL | CAR19 T cell/CAR22 T cell | FC | 1 | Suportive | 10 d/N/A | 3HRZE/9HER | Alive |

| F/16 China | Tuberculosis (mediastinal lymph nodes) | N/A | ALL | CAR19 T cell | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| M/22 Brazil | Tuberculosis (CNS and pulmonary) on +3 mo | Xpert MTB/Rif (CSF) | DLBCL | CAR19 T cell Axicabtagene ciloleucel | FC | 2 | Dexamethasone accumulated dose of 170 mg; tocilizumab 8 mg/kg per dose for 1 dose | No recovery | 2HRZE | Died 5 months after CAR-T due to gastrointestinal hemorrhage |

| N/A USA | Coccidioidomycosis | N/A | N/A | CAR19 T cell | FC | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| F/24 Brazil | Cryptococcus sp. on day +20 | Skin biopsy | ALL | CAR19 T cell Tisagenlecleucel | FC | 3 | Dexamethasone 30 mg total dose; metilprednisolone 790 mg total dose; and tocilizumab 2 doses | No recovery | Not started (postmortem diagnosis) | Died 2 months after CAR-T due to disease progression |

| M/46 UK | Toxoplasma gondii (CNS) on +4 months | Brain biopsy and PCR (CSF) | ALL | CAR19 T cell | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Pyrimethamine sulfadiazine and folinic acid | Alive |

| M/71 The Netherlands | MRI suggestive of toxoplasmosis on day +7 | MRI (serology tests were negative) | DLBCL | CAR19 T cell | FC | 1 | Suportive | N/A | Pyrimethamine sulfadiazine and folinic acid | Alive |

| M/54 USA | T gondii (pulmonary and CNS) on day +67 | Autopsy | DLBCL | CAR19 T cell | FC | 2 | Dexamethasone 10 mg every 6 hours for 3 d, methylprednisolone 1 mg/kg per day for 5 d, and tocilizumab for 3 doses | 26 d/ N/A | Not started (postmortem diagnosis) | Died 70 d after CAR-T due to disseminated toxoplasmosis |

| F/24 Brazil | G Lamblia on day +20 | Molecular panel for diarrhea | ALL | CAR19-T-cell | FC | 3 | Dexamethasone 30 mg total dose, metilprednisolone 790 mg total dose and tocilizumab 2 doses | No recovery | Metronidazole | Died 2 months after CAR-T-cell due to disease progression |

| F/64 Colombia | Trypanossoma cruzi reactivation on day +30 | Blood PCR | DLBCL | CAR19 T cell | FC + dexamethasone and lenalidomide | N/A | N/A | 9 d/N/A | Benznidazole | Alive |

| Sex/age Local . | Type and time∗ of infectious diagnosis . | Diagnosis method . | Hematologic diagnosis . | Type of CAR-T . | Conditioning regimen . | CRS grade . | CRS/ICANS treatment† . | Time to cellular immune recovery, neutrophil/B cells . | Infectious treatment . | Outcomes . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F/9 Born in Pakistan living in Spain for the past 3 y | Tuberculosis (pulmonary) on day +64 | PCR of BAL | ALL | CAR19-T-Cell | FC | 3 | Dexametasone 0.6 mg/kg per day for 13 days; tocilizumab 8 mg/kg per dose for 2 doses; siltuximab 11 mg/kg for 1 dose; anakinra 2 mg/kg per day for 3 d | 5 mo/5 mo | HRZE | Relapse of ALL and died at day +94 |

| M/45 China | Tuberculosis (pulmonary) on day +23 | Xpert MTB/Rif (sputum) | MCL | CAR19 T cell/CAR22 T cell + tandem ASCT | BEAM | 2 | Dexametasone 10 mg for 3 d | 14 d/3 mo | 2HRZE/4HR | Alive |

| F/29 China | Tuberculosis (pulmonary and CNS) on day +66 | Xpert MTB/Rif (CSF) | ALL | CAR19 T cell/CAR22 T cell | FC | 1 | Suportive | 7 d/3 mo | 2HRZE | Relapse of ALL 4 months after CAR-T and lost to FU |

| M/60 China | Tuberculosis (pulmonary and CNS) on +8 mo | Xpert MTB/Rif (PE); TB PCR (CSF) | DLBCL | CAR19 T cell/ CAR22 T cell + tandem ASCT | BEAM | 1 | Suportive | 20 d/10 mo | 2HRZE | Death due to CNS tuberculosis |

| M/23 China | Tuberculosis (pulmonary and nodal) on +10 mo | PCR (mediastinal lymph node biopsy) | DLBCL | CAR19 T cell/CAR22 T cell + tandem ASCT | BEAM | 1 | Suportive | 9 d/13 mo | 3HRZE/9HER | Alive |

| F/63 China | Tuberculosis (subcutaneous and bone) on +11 mo | PCR (subcutaneous nodules biopsy) | FL | CAR19 T cell/CAR22 T cell | FC | 1 | Suportive | 10 d/N/A | 3HRZE/9HER | Alive |

| F/16 China | Tuberculosis (mediastinal lymph nodes) | N/A | ALL | CAR19 T cell | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| M/22 Brazil | Tuberculosis (CNS and pulmonary) on +3 mo | Xpert MTB/Rif (CSF) | DLBCL | CAR19 T cell Axicabtagene ciloleucel | FC | 2 | Dexamethasone accumulated dose of 170 mg; tocilizumab 8 mg/kg per dose for 1 dose | No recovery | 2HRZE | Died 5 months after CAR-T due to gastrointestinal hemorrhage |

| N/A USA | Coccidioidomycosis | N/A | N/A | CAR19 T cell | FC | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| F/24 Brazil | Cryptococcus sp. on day +20 | Skin biopsy | ALL | CAR19 T cell Tisagenlecleucel | FC | 3 | Dexamethasone 30 mg total dose; metilprednisolone 790 mg total dose; and tocilizumab 2 doses | No recovery | Not started (postmortem diagnosis) | Died 2 months after CAR-T due to disease progression |

| M/46 UK | Toxoplasma gondii (CNS) on +4 months | Brain biopsy and PCR (CSF) | ALL | CAR19 T cell | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Pyrimethamine sulfadiazine and folinic acid | Alive |

| M/71 The Netherlands | MRI suggestive of toxoplasmosis on day +7 | MRI (serology tests were negative) | DLBCL | CAR19 T cell | FC | 1 | Suportive | N/A | Pyrimethamine sulfadiazine and folinic acid | Alive |

| M/54 USA | T gondii (pulmonary and CNS) on day +67 | Autopsy | DLBCL | CAR19 T cell | FC | 2 | Dexamethasone 10 mg every 6 hours for 3 d, methylprednisolone 1 mg/kg per day for 5 d, and tocilizumab for 3 doses | 26 d/ N/A | Not started (postmortem diagnosis) | Died 70 d after CAR-T due to disseminated toxoplasmosis |

| F/24 Brazil | G Lamblia on day +20 | Molecular panel for diarrhea | ALL | CAR19-T-cell | FC | 3 | Dexamethasone 30 mg total dose, metilprednisolone 790 mg total dose and tocilizumab 2 doses | No recovery | Metronidazole | Died 2 months after CAR-T-cell due to disease progression |

| F/64 Colombia | Trypanossoma cruzi reactivation on day +30 | Blood PCR | DLBCL | CAR19 T cell | FC + dexamethasone and lenalidomide | N/A | N/A | 9 d/N/A | Benznidazole | Alive |

ASCT, Autologous stem cell transplantation; BAL, bronchoalveolar lavage; BEAM, carmusitine, etoposide, cytarabine, and melphalan; CAR19, CD19-targeted CAR; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; F, female; FC, fludarabine and cyclophosphamide; FU, follow-up; HRZE, rifampicin, isoniazid, pyrazinamide, and ethambutol; M, male; MCL, mantle cell lymphoma; MM, multiple myeloma; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; N/A not available; PE, pleural effusion.

Days after CAR-T infusion.

Includes steroids, tocilizumab, and anakinra.

In our literature review, 8 cases of tuberculosis after CAR-T therapy were identified. The median time to diagnosis was 90 days after infusion (range, 23 days to 11 months). The median age was 26 years (range, 9-63), and half of the patients were male. All were from endemic regions, including 6 from China, 1 from Brazil, and 1 from Pakistan living in Spain. Clinical presentation was heterogeneous: 3 patients (37.5%) had pulmonary disease, 3 (37.5%) had disseminated involvement including the CNS and lungs, and the remaining patients had bone or nodal disease. Underlying malignancies included leukemia in 3 patients (37.5%) and lymphoma in 5 patients (62.5%). Lymphodepletion was performed with fludarabine and cyclophosphamide or BEAM (carmusitine, etoposide, cytarabine, and melphalan) in most cases, and CRS/ICANS management included tocilizumab in 2 patients (25%) and dexamethasone in 3 patients (37.5%). Hematologic recovery was delayed, with a median neutrophil recovery time of 12 days (range, 7-150) and B-cell recovery time of 150 days (range, 90-390). At the last follow-up, 3 patients (37.5%) were alive; 1 death was attributed to tuberculosis, and 2 occurred because of disease progression. All patients with pulmonary or CNS involvement developed infection 2 months after infusion and died. Only 3 of the 8 patients received corticosteroids or other agents for CRS/ICANS, and tuberculosis was diagnosed within the first 3 months in these patients.26,27,31

In addition, in our own cohort, most patients from endemic areas underwent QuantiFERON testing; 2 tested positive and received isoniazid prophylaxis, and none of them developed tuberculosis. One patient who was not screened with QuantiFERON developed disseminated disease 3 months after CAR-T infusion and died 5 months later. The patient was a 22-year-old male with stage IV DLBCL referred from another center, who developed disseminated tuberculosis (CNS and pulmonary) and persistent cytopenias despite supportive measures. He received high cumulative doses of corticosteroids, tocilizumab, and anakinra for CRS/ICANS and ultimately died of complications 5 months after infusion.

In our literature review, we also identified 2 cases of endemic fungal infections: one caused by Coccidioides and the other by Cryptococcus.22 In our cohort, invasive fungal infections occurred in 18% of patients, including early-phase infections by Candida spp., Aspergillus spp., and Cryptococcus sp.

Regarding protozoan infections, 3 cases of toxoplasmosis were described in the literature, all with CNS involvement. One patient was diagnosed at day 7 after infusion and 2 after 2 months. Two patients had lymphoma, and 1 had leukemia; 2 survived, and 1 died. All initially presented with fever and neurological symptoms, and 2 were initially managed as CRS/ICANS, with high cumulative corticosteroid exposure. Final diagnoses included 2 cases of CNS toxoplasmosis and 1 disseminated toxoplasmosis with hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis.28-30 From our center, we report, to our knowledge, the first case of gastrointestinal protozoan infection after CAR-T, with giardiasis diagnosed at day 20 after infusion. Additionally, in our literature review, we identified a case of a 64-year-old Colombian woman who developed reactivation of Trypanosoma cruzi detected by blood PCR on day 30. She had received dexamethasone and lenalidomide during hospitalization and responded favorably to treatment.

Discussion

Our study shows that the overall incidence and timing of bacterial and viral infections after CAR-T therapy are consistent with previous reports, with bacterial infections predominating in the early period and viral reactivations, particularly CMV, occurring without overt disease.9,15,32 These observations reinforce that the pattern of infections in CAR-T recipients mirrors those described in other hematologic contexts, while also underscoring the importance of vigilant monitoring throughout the different postinfusion phases.

The occurrence of tuberculosis after CAR-T therapy deserves particular attention. Most cases from our literature review were reported in patients from endemic regions, suggesting previous latent infection as the likely source.26,27,31 The heterogeneous clinical presentations and frequent occurrence beyond the first months after infusion highlight both the need for long-term vigilance and the potential limitations of current screening practices. Our findings suggest that systematic preinfusion screening, including interferon gamma release assays, is important in patients from tuberculosis-endemic regions, given the delayed immune reconstitution after CAR-T therapy. Although endemic fungal infections remain rare, the few cases reported emphasize the importance of exposure history and risk stratification.22 Invasive fungal infections, particularly those occurring early, highlight the vulnerability of patients in the setting of profound cytopenias and immunosuppressive treatments for CRS and ICANS. Similarly, protozoan infections such as toxoplasmosis, giardiasis, and Chagas reactivation illustrate the unique diagnostic challenges in this population.28-30 These cases demonstrate that early recognition requires a high index of suspicion, especially in patients from or with exposure to endemic areas.

Taken together, these observations indicate that infections after CAR-T therapy extend beyond the classical bacterial and viral spectrum and may involve a wide range of endemic pathogens. In regions with higher prevalence of tuberculosis, parasitic diseases, and certain fungi, preinfusion screening and postinfusion monitoring strategies should be adapted to the local epidemiology. Our data, along with reports from the literature, highlight the need for tailored preventive measures, systematic screening policies, and international collaboration to better define the true incidence of these infections. Ultimately, the integration of endemic pathogens into the risk assessment of CAR-T recipients is critical to improving outcomes in diverse geographic settings.

This study has several limitations. The retrospective and single-center nature of our cohort may limit the generalizability of the findings, and the small number of endemic infections precludes definitive conclusions about their incidence and risk factors. In addition, data extracted from the literature were heterogeneous, with incomplete information regarding preinfusion screening, concomitant therapies, and long-term follow-up. The absence of data on the median duration of infectious complications and median ICU stay represents a limitation as well. Finally, the lack of systematic screening for endemic pathogens in most centers limits accurate incidence estimates. These factors should be considered when interpreting our results.

Conclusion

This study highlights the high incidence of infections in patients undergoing CAR-T therapy, with 60.8% of patients developing infections, particularly in the early phase (within 30 days). Bacterial, viral, fungal, and protozoan infections were common, with notable cases of CMV reactivation, invasive fungal infections, and tuberculosis. Factors such as disease status, elevated CRP levels, and anakinra use were associated with higher infection risk. Our findings emphasize the need for comprehensive infectious disease screening, including endemic infections, to improve patient outcomes during CAR-T therapy.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Editage (www.editage.com) for English language editing.

Authorship

Contribution: M.V.B. and J.S.-F. designed the study and supervised data collection, analysis, and interpretation; A.C. Cortez and V.A.B. collected data; and A.C. Cortez, V.A.B. and A.C. Cordeiro drafted the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Marjorie Vieira Batista, Department of Infectious Diseases and Infection Control, A.C. Camargo Cancer Center, R Prof Antônio Prudente, 211 - Liberdade, São Paulo, SP 01509-001, Brazil; email: marjorie.batista@accamargo.org.br.

References

Author notes

The data sets generated and/or analyzed during this study are not publicly available due to patient confidentiality and institutional restrictions. However, data are available from the corresponding author, Marjorie Vieira Batista (marjorie.batista@accamargo.org.br), upon reasonable request.