Key Points

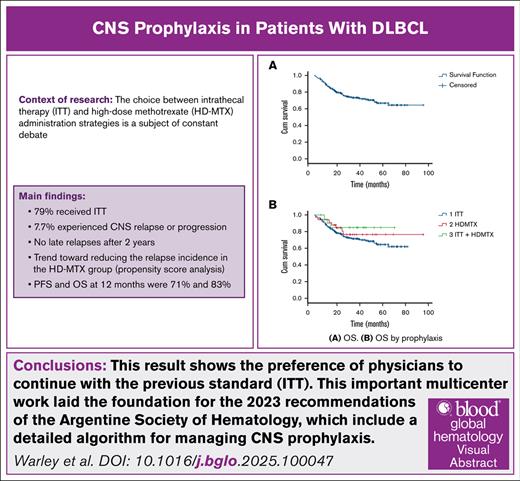

A multicenter retrospective study from Argentina shows the clinical management and limitations of CNS prophylaxis in patients with DLBCL.

Visual Abstract

Central nervous system (CNS) relapse in patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is an infrequent event, and the efficacy of strategies currently used to prevent it has been challenged. This retrospective study involved 262 patients with DLBCL and CNS prophylaxis. Two hundred and seven (79%) patients received intrathecal therapy (ITT), 34 (13%) high doses of methotrexate (HD-MTX), and 21 (8%) both. Twenty patients (7.7%) had CNS relapse with an incidence of 2.8%, 5.8%, and 7.7% at 6, 12, and 24 months, respectively. No difference according to type of prophylaxis was found. Overall survival and progression-free survival for the entire cohort at 6, 12, and 24 months were 94% and 84%, 83% and 71%, 62% and 55%, respectively. ITT was the most commonly used prophylactic strategy, despite international guidelines favoring HD-MTX. We describe an incidence of 7.7% of CNS relapse with no difference according to type of prophylaxis. The clinical benefit of CNS prophylaxis remains an area of uncertainty; prospective studies with sufficient power are required to determine the benefits of these strategies.

Introduction

Central nervous system (CNS) relapse in patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is an infrequent and highly mortal event, raising a significant challenge in clinical management. Over the years, different strategies for prevention and treatment of CNS involvement have been explored in clinical practice: intrathecal therapy (ITT) and high-dose methotrexate (HD-MTX) administration.1,2 However, the choice between these strategies is a subject of constant debate, and recommendations vary in guidelines and clinical practice. Despite efforts to define the most appropriate prevention strategy, there is a noticeable lack of consensus, and there is no solid evidence supporting one strategy over the other.

The role of ITT showed satisfactory results in a limited number of retrospective studies, either as a single strategy or in combination with HD-MTX.3-5 Nonetheless, these results could not be replicated in the post–rituximab era. Regarding HD-MTX therapy, the study by Ong et al demonstrated the greatest benefit in favor of intervention in a multicenter retrospective study.6 Unfortunately, other studies with a similar design could not replicate these differences, and therefore the use of HD-MTX remains controversial.7-11 Despite this, its recommendation persists in national and international guidelines.

To date, there are limited local data on this topic.12 Our study aimed to evaluate the incidence of CNS relapse and survival in patients with DLBCL undergoing various prophylaxis strategies in a real-life setting through a retrospective analysis of a large cohort of patients in Argentina.

Objectives

The primary objective was to calculate the incidence of CNS relapse in patients with DLBCL undergoing CNS prophylaxis, and analyze progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) in a patient cohort. Additionally, we aimed to explore possible differences in these outcomes based on the prophylaxis strategies used as a secondary objective.

Materials and methods

We conducted a multicenter retrospective cohort study in various medical centers, both public and private, with physicians who are members of the Argentinian Society of Hematology. The study period ranged from January 2016 to December 2020. Patients diagnosed with DLBCL according to the 2016 World Health Organization criteria, as well as those with unspecified high-grade B-cell lymphomas and double/triple-hit lymphomas, who received any form of prophylaxis to prevent CNS relapse, were included. We use the databases of each institution, most of them with electronic records. Patients with primary mediastinal lymphoma, CNS involvement at diagnosis, and transformed lymphomas from a previous indolent lymphoma were excluded. Pathological evaluation included determination of the cell of origin by the Hans algorithm, double and triple expressors by immunohistochemistry, and double and triple hits by fluorescence in situ hybridization techniques.13,14

The indication and modality of CNS prophylaxis were at the discretion of the investigators at each center. It is important to consider that the criteria for CNS prophylaxis have evolved over time, even within this cohort, which gathered data over 5 years. As we approach the patients evaluated in 2020, the criteria became more restrictive due to the lack of evidence in patients who were lower-risk (eg, its use was discouraged in cases of involvement of paranasal sinuses, bone marrow, double and triple expressors, among others). All centers had access to the studies to confirm the CNS relapse by brain magnetic resonance imaging, the presence of cells in cerebrospinal fluid by flow cytometry, or brain biopsy.

To assess time to CNS relapse, a competing risks time-to-event analysis was performed, considering death without CNS relapse as a competing event. Follow-up time was considered from the date of initial diagnosis, and the follow-up end was defined as loss of follow-up, relapse, or death. Additionally, an inverse probability weight propensity score was applied to balance potential confounding factors between the ITT and HD-MTX prophylaxis groups. Kaplan-Meier curves were used to analyze OS and PFS, and survival curves were compared using the log-rank test.

Results

A total of 262 patients diagnosed with DLBCL and CNS prophylaxis were included in the study, with median follow-up of 34.6 months (interquartile range [IQR], 18.1-50.4). The median age of the cohort was 63 years (IQR, 53-71), and 54% of patients were male. Median performance status by Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group was 1 (IQR, 0-2), lactate dehydrogenase was elevated in 100 (38%) patients, with a median of 375 U/L (IQR, 224-667, normal range 300 U/L). Extranodal involvement was present in 85% of patients, and 72% presented with stage IV disease at the time of diagnosis. The most common extranodal sites included bone (20%), gastrointestinal tract (16%), and bone marrow (14%). The International Prognostic Index was categorized as high or intermediate/high in 60% of patients, while the Central Nervous System International Prognostic Index (CNS IPI) was classified as intermediate in 47% and high in 32% of patients. We had a considerable number of patients not evaluated for cell of origin (11%), double expressers (26%), and double hits (75%; Table 1). Nearly 90% of patients underwent CNS evaluation with magnetic resonance imaging (7%), cerebrospinal fluid study by flow cytometry alone (52%), or both (31%).

Baseline characteristics

| Baseline characteristics . | Total, N = 262 . | ITT, n = 207 . | HD-MTX, n = 34 . | Both, n = 21 . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diagnosis, n (%) | .38 | ||||

| DLBCL NOS | 229 (87.4) | 183 (88.4) | 30 (88.2) | 16 (76.2) | |

| DHL/THL | 12 (4.6) | 10 (4.8) | 1 (2.9) | 1 (4.8) | |

| HGBL NOS | 21 (8) | 14 (6.8) | 3 (8.8) | 4 (19) | |

| Sex, n (%) | .82 | ||||

| Male | 141 (53.8) | 97 (46.9) | 14 (41.2) | 10 (47.6) | |

| Female | 121 (46.2) | 110 (53.1) | 20 (58.8) | 11 (52.4) | |

| Age (median, IQR) | .14 | ||||

| 63 (53-71) | 64 (53-72) | 58 (53-65) | 60 (50-64) | ||

| HIV-positive, n (%) | .96 | ||||

| 21 (8) | 17 (8.2) | 3 (8.8) | 1 (4.8) | ||

| EN sites, n (%) | .01 | ||||

| 0 | 40 (15.3) | 33 (15.9) | 7 (20.6) | 0 (0) | |

| 1 | 113 (43.1) | 96 (46.4) | 7 (20.6) | 10 (47.6) | |

| ≥2 | 109 (41.6) | 78 (37.7) | 20 (58.8) | 11 (52.4) | |

| IPI, n (%) | .69 | ||||

| 0-1 | 48 (18.4) | 36 (17.5) | 9 (26.5) | 3 (14.3) | |

| 2 | 53 (20.3) | 42 (20.3) | 4 (11.8) | 7 (33.3) | |

| 3 | 71 (27.2) | 57 (27.5) | 9 (26.5) | 5 (23.8) | |

| ≥4 | 86 (33) | 68 (33) | 12 (35.3) | 6 (28.6) | |

| NE | 3 (1.1) | 3 (1.5) | 0 (0) | (0) | |

| CNS IPI, n (%) | .49 | ||||

| 0-1 | 53 (20.3) | 39 (18.9) | 11 (32.4) | 3 (14.3) | |

| 2-3 | 122 (46.7) | 100 (48.5) | 13 (38.2) | 9 (42.9) | |

| ≥4 | 83 (31.8) | 64 (30.9) | 10 (29.4) | 9 (42.9) | |

| NE | 3 (1.1) | 3 (1.5) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| COO, n (%) | .71 | ||||

| No GC | 102 (38.9) | 81 (39.1) | 15 (44.1) | 6 (28.6) | |

| GC | 131 (50) | 102 (49.3) | 17 (50) | 12 (57.1) | |

| NE | 29 (11.1) | 24 (11.6) | 2 (5.9) | 3 (14.3) | |

| DEL, n (%) | .12 | ||||

| Yes | 78 (29.8) | 61 (29.5) | 9 (26.5) | 8 (38.1) | |

| No | 115 (43.9) | 85 (41.1) | 18 (52.9) | 12 (57.1) | |

| NE | 69 (26.3) | 61 (29.5) | 7 (20.6) | 1 (4.8) | |

| DHL, n (%) | .29 | ||||

| Yes | 8 (3.1) | 7 (3.4) | 1 (2.9) | 0 (0) | |

| No | 57 (21.8) | 40 (19.3) | 9 (26.5) | 8 (38.1) | |

| NE | 197 (75.2) | 160 (77.3) | 24 (70.6) | 13 (61.9) | |

| CNS evaluation, n (%) | .1 | ||||

| MRI | 17 (6.5) | 14 (6.8) | 2 (5.9) | 1 (4.8) | |

| CSF cytology | 137 (52.3) | 111 (53.6) | 16 (47.1) | 10 (47.6) | |

| MRI + CSF cytology | 81 (30.9) | 63 (30.4) | 8 (23.5) | 10 (47.6) | |

| None | 27 (10.3) | 19 (9.2) | 8 (23.5) | 0 | |

| First-line treatment, n (%) | .71 | ||||

| R-CHOP | 192 (73.3) | 147 (71) | 28 (82.4) | 17 (81) | |

| DA-EPOCH-R | 62 (23.7) | 42 (52.1) | 6 (17.6) | 4 (19) | |

| R-HyperCVAD | 3 (1.1) | 3 (1.4) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Other | 5 (1.9) | 5 (2.4) | 0 (0) | (0) |

| Baseline characteristics . | Total, N = 262 . | ITT, n = 207 . | HD-MTX, n = 34 . | Both, n = 21 . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diagnosis, n (%) | .38 | ||||

| DLBCL NOS | 229 (87.4) | 183 (88.4) | 30 (88.2) | 16 (76.2) | |

| DHL/THL | 12 (4.6) | 10 (4.8) | 1 (2.9) | 1 (4.8) | |

| HGBL NOS | 21 (8) | 14 (6.8) | 3 (8.8) | 4 (19) | |

| Sex, n (%) | .82 | ||||

| Male | 141 (53.8) | 97 (46.9) | 14 (41.2) | 10 (47.6) | |

| Female | 121 (46.2) | 110 (53.1) | 20 (58.8) | 11 (52.4) | |

| Age (median, IQR) | .14 | ||||

| 63 (53-71) | 64 (53-72) | 58 (53-65) | 60 (50-64) | ||

| HIV-positive, n (%) | .96 | ||||

| 21 (8) | 17 (8.2) | 3 (8.8) | 1 (4.8) | ||

| EN sites, n (%) | .01 | ||||

| 0 | 40 (15.3) | 33 (15.9) | 7 (20.6) | 0 (0) | |

| 1 | 113 (43.1) | 96 (46.4) | 7 (20.6) | 10 (47.6) | |

| ≥2 | 109 (41.6) | 78 (37.7) | 20 (58.8) | 11 (52.4) | |

| IPI, n (%) | .69 | ||||

| 0-1 | 48 (18.4) | 36 (17.5) | 9 (26.5) | 3 (14.3) | |

| 2 | 53 (20.3) | 42 (20.3) | 4 (11.8) | 7 (33.3) | |

| 3 | 71 (27.2) | 57 (27.5) | 9 (26.5) | 5 (23.8) | |

| ≥4 | 86 (33) | 68 (33) | 12 (35.3) | 6 (28.6) | |

| NE | 3 (1.1) | 3 (1.5) | 0 (0) | (0) | |

| CNS IPI, n (%) | .49 | ||||

| 0-1 | 53 (20.3) | 39 (18.9) | 11 (32.4) | 3 (14.3) | |

| 2-3 | 122 (46.7) | 100 (48.5) | 13 (38.2) | 9 (42.9) | |

| ≥4 | 83 (31.8) | 64 (30.9) | 10 (29.4) | 9 (42.9) | |

| NE | 3 (1.1) | 3 (1.5) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| COO, n (%) | .71 | ||||

| No GC | 102 (38.9) | 81 (39.1) | 15 (44.1) | 6 (28.6) | |

| GC | 131 (50) | 102 (49.3) | 17 (50) | 12 (57.1) | |

| NE | 29 (11.1) | 24 (11.6) | 2 (5.9) | 3 (14.3) | |

| DEL, n (%) | .12 | ||||

| Yes | 78 (29.8) | 61 (29.5) | 9 (26.5) | 8 (38.1) | |

| No | 115 (43.9) | 85 (41.1) | 18 (52.9) | 12 (57.1) | |

| NE | 69 (26.3) | 61 (29.5) | 7 (20.6) | 1 (4.8) | |

| DHL, n (%) | .29 | ||||

| Yes | 8 (3.1) | 7 (3.4) | 1 (2.9) | 0 (0) | |

| No | 57 (21.8) | 40 (19.3) | 9 (26.5) | 8 (38.1) | |

| NE | 197 (75.2) | 160 (77.3) | 24 (70.6) | 13 (61.9) | |

| CNS evaluation, n (%) | .1 | ||||

| MRI | 17 (6.5) | 14 (6.8) | 2 (5.9) | 1 (4.8) | |

| CSF cytology | 137 (52.3) | 111 (53.6) | 16 (47.1) | 10 (47.6) | |

| MRI + CSF cytology | 81 (30.9) | 63 (30.4) | 8 (23.5) | 10 (47.6) | |

| None | 27 (10.3) | 19 (9.2) | 8 (23.5) | 0 | |

| First-line treatment, n (%) | .71 | ||||

| R-CHOP | 192 (73.3) | 147 (71) | 28 (82.4) | 17 (81) | |

| DA-EPOCH-R | 62 (23.7) | 42 (52.1) | 6 (17.6) | 4 (19) | |

| R-HyperCVAD | 3 (1.1) | 3 (1.4) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Other | 5 (1.9) | 5 (2.4) | 0 (0) | (0) |

GC, germinal center; COO, cell of origin by Hans algorithms; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; DEL, double expressor; DHL/THL, double-hit/triple-hit lymphoma; EN, extranodal; HGBL, high-grade B-cell lymphoma; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; NE, not evaluated; NOS, not otherwise specified; R-CHOP, rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone; DA-EPOCH-R, dose-intensified regimen dose-adjusted etoposide, prednisone, vincristine, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, and rituximab; R-HyperCVAD, rituximab, hyperfractionated cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin, and dexamethasone.

All patients received immunochemotherapy, rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (R-CHOP) in 73% and the dose-intensified regimen dose-adjusted etoposide, prednisone, vincristine, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, and rituximab (DA-EPOCH-R) in 24%. ITT was administered in 79% of patients, HD-MTX in 13%, and only 8% received both forms of prophylaxis. The median number of ITT applications was 4 (IQR, 1-6). Regarding HD-MTX, 53% of patients received intercalated treatment, and 47% received end-of-treatment prophylaxis, with a median number of cycles of 3 (IQR, 1.5-3.5). Prophylaxis-related toxicity (regardless of the strategy) was observed in 16% of patients, resulting in delays and discontinuation of systemic chemotherapy in 9% and 8%, respectively.

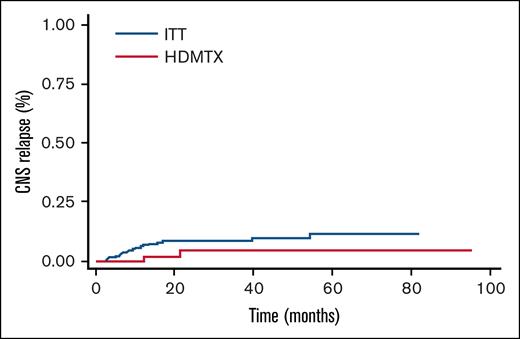

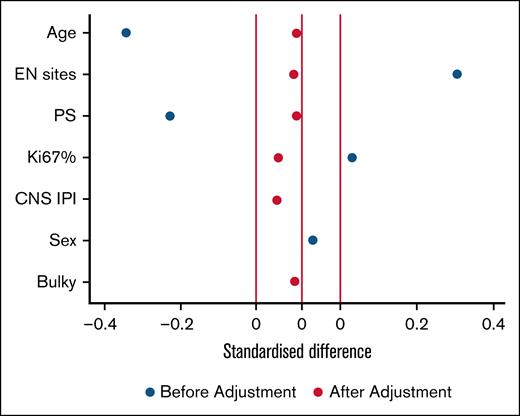

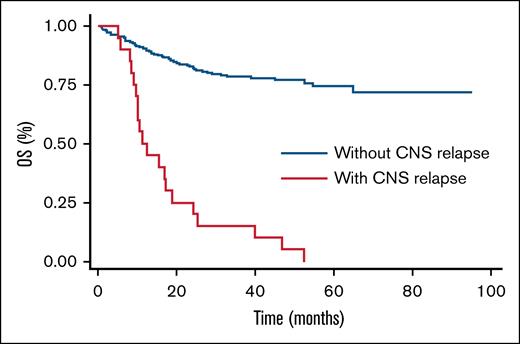

Among studied patients, 7.7% experienced CNS relapse or progression (competing risks time-to-event analysis). Incidence rates were 2.8%, 5.8%, and 7.7% at 6, 12, and 24 months, respectively, and all these patients died due to disease progression (Figure 1). Only 1 patient relapsed between 12 and 24 months, and there were no late relapses after 2 years. Additionally, significant differences in the incidence of CNS relapse at 24 months were observed based on CNS IPI scores: 4% for low scores, 6.5% for intermediate scores, and 12% for high scores (P = .05). If we take into account the International Prognostic Index score, we had 4% relapses (2/46 patients) with a low score, 9.5% (5/48 patients) with an intermediate/low score, 4% (3/68 patients) with an intermediate/high score, and 10.5% (9/77 patients) with a high score (P = .5). No significant differences were found in the type of prophylaxis used, although the propensity score indicated a trend toward reducing the relapse incidence in the HD-MTX group (odds ratio = 0.3 [95% confidence interval, 0.07-1.5]). We considered the following variables: age, number of extranodal sites, performance status, Ki-67 proliferation index, CNS IPI, sex, and bulky, as the most important to adjust in the model. As can be seen in Figure 2, the standardized difference after adjustment was well balanced, giving the model robustness. Regarding the type of relapse, in 19 out of the 20 events, we were able to collect data on the type of relapse, with 9 (48%) being parenchymal, 5 (26%) meningeal, and 5 (26%) both parenchymal and leptomeningeal. Six (30%) CNS relapses were isolated, while the remaining 14 (70%) were also systemic. Finally, the median OS in patients with CNS relapse was 11 months vs not reached in patients without CNS relapse (P = .00; Figure 3).

Propensity score model. The figure shows how the model fits the selected variables. Starting with unbalanced baseline characteristics that could act as confounders (blue dots), and ending with a balanced distribution of the same variables (red dots). EN, extranodal; Ki67%, Ki-67 proliferation index; PS, performance status.

Propensity score model. The figure shows how the model fits the selected variables. Starting with unbalanced baseline characteristics that could act as confounders (blue dots), and ending with a balanced distribution of the same variables (red dots). EN, extranodal; Ki67%, Ki-67 proliferation index; PS, performance status.

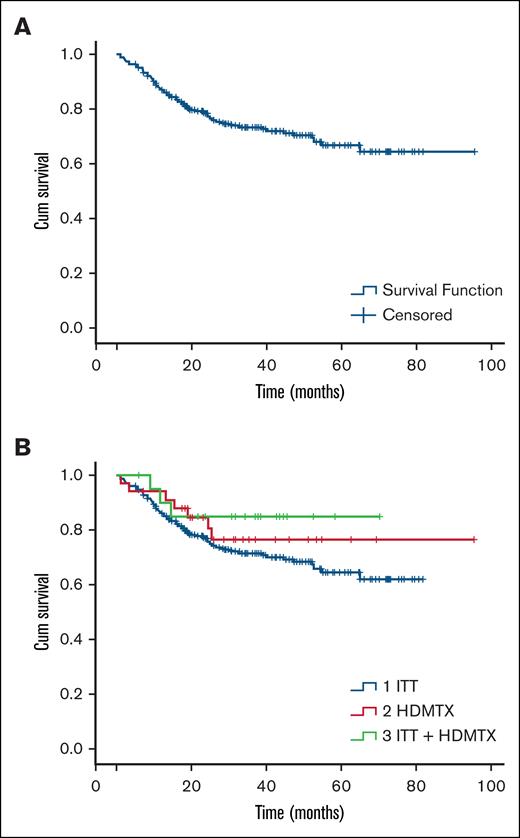

PFS and OS for the entire cohort at 6, 12, and 24 months were 84% and 94%, 71% and 83%, 55% and 62%, respectively. No significant differences were observed in PFS and OS based on the type of prophylaxis used (Figure 4). No significant risk factors for CNS relapse were found in the bivariate analysis.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the largest cohort of patients with CNS prophylaxis in DLBCL in Latin America. In this retrospective analysis, ITT prophylaxis was most commonly used, contrasting with the most recent recommendations from international guidelines where HD-MTX represents the most recommended one.1,15,16

Most patients (90%) had CNS involvement assessment at diagnosis, confirming the absence of CNS compromise. This assessment was not uniformly performed, reflecting lack of standardization in our regional practice. However, we describe an incidence of 7.7% CNS relapse at 24 months regardless of the type of prophylaxis. This incidence correlates with other studies in the rituximab era, showing incidences between 3% and 10% on average, depending on risk, at 5 years.8,17-20 Strikingly, the incidence in our study is on average equidistant between the relapse percentage for the intermediate CNS IPI group (3.4%) and the high CNS IPI group (10.2%) from the original CNS IPI score study described by Schmitz et al. In that study, extranodal site >1 and advanced stage were present in 22% and 53%, respectively, compared with 85% and 72% in our study. While these risk characteristics are enriched in our study, it is important to remember that more extranodal sites are no longer considered risk factors for CNS relapse per se.21 Frontzek et al showed in a retrospective study of >5000 patients the clinical characteristics of CNS relapses. Strikingly, 18% of the patients experienced late relapses after 2 years. Once again, the 2-year OS rate following confirmed relapse was <15%.22 Given the median follow-up of <3 years in our study, long-term follow-up will be needed to assess the occurrence of any late relapses.

Regarding prophylaxis type, evidence remains controversial. ITT was evaluated in the rituximab era in a meta-analysis of >7000 patients by Eyre et al.2 The intervention did not prove to be beneficial in univariate or multivariate analysis, and is not complication free. HD-MTX was evaluated over the last decade by different authors through retrospective studies. The study with the largest number of patients demonstrating the benefits of intervention is that of Ong et al: this multicenter study with 226 patients who were high-risk, where 29% received HD-MTX, showed a decrease from 14.6% to only 3% in the compared and propensity score-adjusted group.6 Other retrospective cohorts designed to answer the same question could not reproduce this benefit.7-11 Our study once again shows no benefit in the use of HD-MTX compared with ITT, with a propensity score with a low odds ratio of 0.3 but with a confidence interval crossing 1 and therefore not statistically significant. Similar findings were found in the study by Yahng et al, the only prospective and randomized study to date, where there was no difference between prophylaxis, although a delay in CNS relapse was seen in the HD-MTX group with a median of 12 months to CNS relapse vs 4.4 in the ITT group.23 This trend toward the benefit of HD-MTX could indicate a marginal benefit, which we cannot fully see due to the heterogeneity of the patients (especially in the numerous retrospective studies published), plus the difficulty of recruiting an adequate number, especially of patients with a high risk of CNS relapse.

To our surprise, in our study, most patients (79%) received ITT, reflecting institutional practice rather than a demonstrated preference based on efficacy. These findings reflect persistence of historical practice patterns, until there is firm evidence to justify the change. In addition, there is genuine concern about the logistics involved in HD-MTX, which can only be carried out in centers of medium to high complexity given the increase in days of hospitalization, the need for specialized nursing for alkalinization, infusion and controls, and the need for a laboratory with methotrexate dosage measurement. Finally, despite the fact that only a small percentage received HD-MTX, following the current standard, the rate of CNS relapse remains similar to the CNS IPI score. This suggests that the prophylaxis may not have a clear clinical impact.

Our study has inherent weaknesses in its design. Like all previous studies published to date, the retrospective design introduces biases and confounders among the different populations to analyze. Therefore, the use of the propensity score increases the robustness of the results and generates comparable populations by balancing the confounders chosen in the model. On the other hand, collected data may not be complete given the retrospective design; however, in our analysis, most requested data, including the most challenging clinical data to collect, could be documented, with the exception of grading of adverse events. Data regarding prophylaxis toxicity were only collected to address the rate of discontinuation or delay in systemic chemotherapy, not being able to conclude about specific prophylaxis-related toxicities. The percentage of missing data was remarkably low, probably because the treatment of these patients occurs in high-complexity centers, most with electronic medical records.

As a strength, we emphasize the importance of this Argentine real-world analysis considering the low incidence of CNS relapse in patients with DLBCL. Our results underscore an unmet need for more robust clinical data to address the true implication of prophylaxis, to guide our clinical practice. In the future, we will need prospective studies, ideally, with a placebo arm, where confounders can be adequately balanced, comparing a standardized and uniform prophylaxis strategy: HD-MTX doses, intercalated or end-of-treatment HD-MTX, number of cycles, and the same infusion protocol for all study patients, to finally put an end to the historical controversy in this area.

Having local data on the use of prophylaxis is of great importance for our region, where the logistics of HD-MTX infusions and the management of its toxicities, in the context of a lack of clear evidence of its benefit, could lead centers with limited infrastructure to opt against HD-MTX or any form of prophylaxis. On the other hand, centers with greater infrastructure might also choose to limit prophylaxis to a subgroup of patients who were very high-risk. This important multicenter work laid the foundation for the 2023 recommendations of the Argentine Society of Hematology, which include a detailed algorithm for managing CNS prophylaxis. Based on this and other current evidence and expert consensus, we believe the best recommendation is to administer IV HD-MTX after documenting metabolic complete remission following the completion of systemic therapy; however, the final decision should be made on a case-by-case basis. Nevertheless, we acknowledge that further evidence is needed to determine whether this strategy is truly necessary in all cases.24

Authorship

Contribution: All authors contributed equally to the development of this consensus program, actively participated in the formulation, review, and revision of the manuscript, and approved the final version for submission.

All authors are members of the Lymphoma Subcommittee of the Argentinian Society of Hematology.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Fernando Warley, Hematology Service, Internal Medicine Department, Hospital Italiano de Buenos Aires, Tte Gral J. D. Perón, 4190 Buenos Aires, Argentina; email: ferwarley@gmail.com.

References

Author notes

Additional data are available from the corresponding author, Fernando Warley (ferwarley@gmail.com), on request.